#posting about taxonomy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wisent Bos bonasus

Observed by anikeevv, CC BY-NC

Are bison Bison?

The two living species of wild cattle generally known as "bison" - American bison Bos bison and European bison or wisent Bos bonasus - have traditionally been in a genus of their own, the eponymous Bison, separate from other close relatives of domestic cattle. Genetic research, however, shows that the two bison are actually within the "true" cattle genus Bos, closely allied to the yaks Bos mutus and Bos grunniens. Keeping them separated in their own genus Bison would render Bos paraphyletic - that is, a lineage that is based around common ancestry but does not include all of that ancestor's descendants. The alternatives would be to split the genus Bos into several more-restricted genera (Poephagus for the yaks and Bibos for the South and Southeast Asian wild cattle) to keep the bison Bison, which is not ideal given the obvious close affinity that these cattle share; or, to lump the bison back into Bos. As should be obvious, the latter is the course followed here, as well as by the American Society of Mammalogists.

Ref:

American Society of Mammalogists. Bos bonasus Linnaeus, 1758. ASM Mammal Diversity Database.

Grange, T, J-P Brugal, L Flori, M Gautier, A Uzunidis, and E-M Geigl. 2018. The evolution and population diversity of bison in Pleistocene and Holocene Eurasia: Sex matters. Diversity 10(3):65.

Wang, K, JA Lenstra, L Liu, Q Hu, T Ma, Q Qiu, and J Liu. 2018. Incomplete lineage sorting rather than hybridization explains the inconsistent phylogeny of the wisent. Communications Biology 1:169.

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

sapience play: to coin a term

was trying to explain to friends a couple years ago that what i find fun in pet play is not necessarily the collars/leashes stuff it's the 'no one will look at you like a person' and similar dehumanization/TPE elements. and that got me into thinking about a list of tropes that would fall under this term, like:

brainwashing

mind break

reprogramming

hive mind

feeblemind

objectification

hypnosis

dollification

like, there's a family of not-necessarily-kink stuff with some broad similarities that falls under this, the same way 'impact play' encompasses a wide swathe of stuff that scratches a certain similar itch, so it's useful to have a term for it. though unlike impact play, the only place you're likely to find sapience play applied is in fantasy/roleplay/written form, just because it's not actually possible to plug someone's brain into a computer and erase their memories.

#posting this so i can have a definition to link back to going forward because i find it useful#and i don't know enough about tvtropes to make a page#and while i was reminded of this by the discussions happening in unpretty's kink taxonomy tag i don't think it's quite part of that convo#sroloc babbles#sapience play

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey does anyone wanna hear me talk about our interpretation of the minecraft lore and taxonomy of the mobs + some of the flora

#gremlin ramblings#altoclef.exe#Im cooking up an au (its an scp Rebar Antlers but make it Warden x Creaking au lmao)#Its so far removed from scp itself though. Im basically just taking the characters and throwing them into the world#I infodumped to our friends about it but we need to flesh it out more#scp#minecraft#scp au#minecraft au#minecraft taxonomy#minecraft worldbuilding#I have some Very Specific ideas about the lore of minecraft that I need to talk about to more people ot Im gonna loose my mind#If we fall asleep before we can post it tonight then well post it in the morning hopefully lmao someone will just need to remind us

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

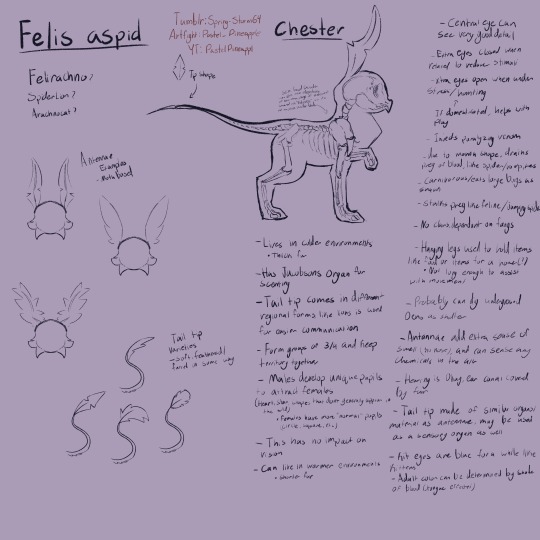

Okay so I am about to be so incredibly normal. I made a little species in high school and have one (1) character of that species named Chester whom I love very much, I decided to create a little, research paper? about them because I have figured out a lot of things except for the Common Name for the species :)

Going to put it all below the cut but AHHH I am NOT NORMAL ABOUT MY THINGS !!! also VOTE AT THE BOTTOM TO HELP ME FIGURE OUT A COMMON NAME!! please :)

Felis aspid

(Feline family, aspid with ancient Greek roots meaning venomous)

----------

The example of the skeletal structure is my own boy, Chester. The skeleton is very feline-like closest to a domestic cat, the only difference being that extra pair of legs with the semi-fused shoulder blades.

Those upper legs, or "Pedipalps," have a lower range of movement than the front legs, making them useless for movement but very good for carrying things. Kits are carried by the scruff, but other items like some types of prey and supplies for building nests in the wild are carried using these legs. Domesticated ones may use them to carry around their toys if preferred.

These Pedipalps are also very powerful and useful for digging out dens in the wild. They will find a suitable area and dig a fully underground home for their pack, always living in groups of 3 or 4.

----------

These creatures have Antennae closest compared to a moth. The antennae are used for scenting the area as their sense of smell in the nose is not that strong, this combined with the "Jacobson's Organ" still gives them a pretty good idea of the smells in the area, though not in the same way a Feline or Canine may detect those smells.

The tip of the tail is made of the same kind of fur/feathering as the antennae, while thought that it coupe also be used for "scenting" it is mostly used as a sensory organ to keep better track of surroundings as they don't have a good sense of hearing. The different shapes also seem to be used for easier communication and signaling between their pack, family, or even strangers encountered nearby.

----------

The single eye in the center is very interesting. It is not the only eye they have. There are six more eyes placed in groups of three on either side of their large eye.

The center eye helps them see in much more detail, maybe being able to see or capture movement that would be lost to other species. While those other eyes help hone in on what they're hunting, making the creature more aware of their surroundings, usually these eyes are closed when the animal is relaxed as they have no need for it unless in a higher stress situation. This same behavior can be observed in those domesticated during play.

The eye is also interesting because it is a form of sexual dimorphism (while not always, is the case for 90% of the population). The males tend to form a much more interesting shape of pupil as they grow older, like a star or heart shape, that don't seem to naturally occur. While the females have more "boring" shapes that you may be able to find in other species of animal, like simple circles or squares. This has no effect on their sight.

The more interesting a pupil shape is to a female, the more interested she is in that male

Another fun fact about the eye is that Kits will have blue eyes for a few weeks after being born just like kittens do, they eventually grow into their adult color which, if you know what you are doing can be found out before that point. The color of the eye is completely dependent on the color of their blood and organs, like birds of paradise, this is their dash of color to attract mates.

----------

Their hunting style is very comparable to a regular feline. They will stalk their prey before jumping out and killing it. The key difference is that unlike most felines, they do not have retractable claws, only having small points that barely do damage to another, relying entirely on their fangs and venom.

Yes! These guys are venomous! Not any large amount like their name might imply, but enough to paralyze, at most, an animal the size of small rabbit completely. While taking on bigger prey is an issue for one, when hunting in a pack, they can easily take down something much bigger with the combined use of paralyzing venom.

The usual prey they hunt individually. However, are small animals like mice, birds, shrews, and in some places, large insects like tarantulas. Because their mouths are not built for chewing, they will use their fangs to suck the blood out of their prey, like a spider eats bugs or a vampire bat.

----------

Most wild examples live in colder climates, resulting in a much thicker fur and in a lighter color for camouflage, but there are examples of them living in warmer climates, with both a thinner fur type and completely different, and usually darker, coloring. Domesticated animals can come at almost any shape and form now.

----------

Images Below

(Wild mother with young kit)

(Domesticated Male)

(Domesticated Female)

(Female Kit, parents are previous two listed)

----------

The wild one you will notice has camouflaging most similar to wildcats that live in snowy areas, the light coloring allowing her to blend in with the snow.

The Domesticated ones however, you can more closely compare to a domestic tabby cat, with colors ranging from one solid color to markings just like a house cat.

Another thing of note is that you can see more clearly here how the Male and Female Dimorphism with the pupils looks like with the female having a square pupil and the male having a "heart" shaped pupil, while the kit still hasn't developed her eye color or shape, while she is young it will stay round and black, until the color comes in once she's older.

----------

THAT'S ALL I GOT I hope it made sense, I love these little things and anyone that sees this post should make one and tag me !!! I don't have super established or hard rules on the 'looks' side of things but go crazy I wanna see !!!!!!

and here's the poll :)

and please don't be shy about replying or tagging I want to see what people think of them!!

#storm-talks#storm-draws#Felis aspid#honestly i think felirachnos has a ring to it but there could always be something better yknow#and like idk i dont know if id walk into a shelter going “i wanna look at the felirachnos” if that makes sense#also lmk if anything in the post doesn't make sense#send an ask or reply or something i want to talk about these cretures#going to be working on a species sheet with some examples as well to make your own! if you want to wait for that#i will be tagging for a little bit of reach on tumblr now :)#taxonomy#binomial nomenclature#naming#zoology#original character#original species#oc#my oc#artists on tumblr#digital art#my art#original art

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh no ive started "are slugcats rodents" discourse in my notes

#case files#unfortunately i suffer from Believing Everything Disease so i never thought to question whether the echo was wrong about them being rodents#honestly even if theyre not really rodents i believe theyre probably the rw equivalent/they fill a similar ecological niche#also because of the thing the devs said about this game being Subway Rat Simulator#or theyre like weasels or some shit idk taxonomy#but anyway the point is oopsie i shouldnt have said canonically in that post

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A thing about the anonymous internet is that on it you are first and foremost your words. And how or if other people decide to sort you into The Gender Binary™️ based on your words is a thing that says far far far more about them than it does about you. And this is why you will likely never see a pronoun in my bio

#gender: well that's a you problem and not a me problem isn't it?#(i appreciate and respect that others have different feelings about this. the point is there should be space for personal feelings i m h o)#gender stuff#taxonomy tag#social media#my posts

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

and then we did not gooooo

#This was in my drafts.#It’s so fucking funny because I actually did indeed have the intention of making a post about demon taxonomy#Mostly to distinguish demons like Diavolo (fur-tailed) and Abbacchio (smooth-tailed)#As well as to distinguish head-horn demons from face-horn demons.#I got distracted trying to fucking figure out if shapeshifters were sponges#So much so I simply did not make the fucking post.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm having so much fun with that zoo website.

Is fish? No. Is reptile? No. Is dolphin? No. Is carnivore? Yes. Is feline? No. Bear? Yes, which? Black? No. Polar? Yes, yay!

Is fish? No. Is reptile? Yes. Is bird? Yes!! Is chicken??? No, too far! Is ostrich? Not far enough! Is eagle, falcon, seagull, dove, flamingo? Nope!

(I don't know enough about bird families, my dude!!!)

(Then I realize I'm ignoring a very important group)

Is blackbird? Warmer. Is sparrow? Warmer.

(What's a cousin of a sparrow???)

Is blue jay? No, you absolute buffoon.

(Uuuuh, okay, small birds. Tweet, tweet. What about pet birds?)

Is canary? Yes, a yellow one, yay!

#none of these are the daily animal :) no spoilers#this is practice#i was about to name all english words I know for birds people keep as pets#this is also a challenge on my english vocab not just taxonomy#fun!!!!!#i excluded sponges immediately because lol boring. but i haven't anything below chordata. where my jellyfish representation??#i brought out the dolphin early cuz those bastards are funky and give me a lot of info#twilit posts

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've noted before that the taxonomy followed on this blog cleaves to my own opinions and is not beholden to any single authoritative source, but the Society For Marine Mammalogy is my standard reference point for the taxonomy of those most wonderful of even-toed ungulates, the cetaceans.

Now, though, I am breaking from their taxonomy by following the 2025 results from Galatius and colleagues on the generic arrangement of the six dolphins traditionally grouped together in the genus Lagenorhynchus, familiarly called "lags". It has been increasingly appreciated since the late 1990s, as the Society For Marine Mammal notes in its taxonomic annotations, that Lagenorhynchus as traditionally defined is polyphyletic; that is, the species included there are actually distantly related and do not form a group with each other to the exclusion of other dolphin species.

While taxonomic revisions for this genus have been proposed before, the Society For Marine Mammalogy did not vote to integrate these into its formal taxonomy due to some lingering uncertainties, particularly regarding the relationship between the Peale's dolphin "Lagenorhynchus" australis, hourglass dolphin "Lagenorhynchus" cruciger, and the small blunt-snouted dolphins Cephalorhynchus spp. I feel that the conclusions reached by Galatius and colleagues (2025), which align with earlier findings as reported therein, are robust enough to alleviate these uncertainties, resting on multiple lines of genomic evidence as well as morphological and acoustic data.

The arrangement of the lags that will be used in this blog is listed below:

Atlantic white-sided dolphin Leucopleurus acutus: Though it has been recovered as the sister species to the white-beaked dolphin (see below), recent phylogenies find this to be the basalmost of the living delphinids, and it is distinguishable morphologically and acoustically.

White-beaked dolphin Lagenorhynchus albirostris: This is the genotypical species for Lagenorhynchus and thus remains unchanged.

Dusky dolphin Aethalodelphis obscurus: This and the following species are clearly very similar, and are united together in this new genus, meaning "sooty dolphin", coined by Galatius and colleagues (2025).

Pacific white-sided dolphin Aethalodelphis obliquidens: The second species transferred to the new genus.

Peale's dolphin Cephalorhynchus australis: The alternative taxonomic scheme championed by Vollmer and colleauges (2019) - and the one recently adopted by iNaturalist for its taxonomy - is to unite this species, the previous two, and the following one in the genus Sagmatias. Peale's dolphin is the type species for Sagmatias. The recent study recovers this and the hourglass dolphin (see below) as sister species, with the sister to this pair being the Haviside's dolphin Cephalorhynchus heavisidii. Rather than splitting up Cephalorhynchus, the preference seems to be adding these dolphins to it.

Hourglass dolphin Cephalorhynchus cruciger: Poorly-known, but established as a close relative of Peale's dolphin; it has now moved with it to Cephalorhynchus.

For what it's worth, I would not be surprised if the Society For Marine Mammalogy adopts this or a similar taxonomy in the near future. While there's always room for surprises with more research (a reduced Sagmatias of the Peale's and hourglass [and possibly Haviside's?] dolphins divided from Cephalorhynchus seems plausible), I am comfortable employing this new arrangement here. It's worth remembering that taxonomic reshuffling isn't a bug, it's a feature - the acquisition of new data, improved and more thorough analyses, and rearrangement of how animals are classified are all in service of a better understanding of these animals' evolutionary histories.

Ref.:

Galatius, A, CC Kinze, MT Olsen, J Tougaard, D Gotzek, MR McGowen. 2025. Phylogenomic, morphological and acoustic data support a revised taxonomy of the lissodelphine dolphin subfamily. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 205:108299.

Vollmer, NL, E Ashe, RL Brownell Jr., F Cipriano, JG Mead, RR Reeves, MS Soldevilla, R Williams. 2019. Revision of the dolphin genus Lagenorhynchus. Marine Mammal Science 35(3):957-1057.

and references therein

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do you... how do you translate "Realm" into Slovak if "ríša" is already taken by "Kingdom"?

#viral taxonomy#can't find any slovak resource about the ICTV taxonomy#do i just#or#i dunno#van's post

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughtful panel from Soul Eater post chapter 3

#soul eater post#soul eater#manga panel#reaction image#death the kid#liz thompson#patty thompson#spidersense#remember being 8 and this factoid getting repeated every week as some big mindblowing revelation#but especially cause who gives a shit a bug is a bug nobody cares about taxonomy#chapter 3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

not pictured is the goth clouded leopard girl who bought the cigarettes w her fake id

my name's cougar but my friends call me mountain lion and my mama calls me puma and today's my first day at big cat high. i'm so nervous i hope they don't realize i'm not panthera >ܫ<

#once again. posts that were made for me and my insane opinions about cat taxonomy ghdhfhdhdh#jordan's drawing again

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

.

#saw that post that’s like five topics you could talk about for an hour with no prep#y’all can’t talk for an hour unprompted ?#like i could do pokémon: types and advantages-sandstorm types-generational differences-mythologies#music: particular artists-culture on the world stage-historical crossovers and influences#theater: history-shakespeare-expressionism-absurdism#animals: sharks-evolution-general taxonomy#i’m good on any of those for At Least a solid 45 as standalones

0 notes

Text

Being trans in the specific way I am is so wild sometimes.

I’m not a woman, but everyone around me sees me a woman shaped. I’m like a hyena. People see my shape and go “oh that’s a type of dog!” But I am not a type of dog. I am a type of cat. Just like hyenas.

But I filled the ecological niche most often filled by a type of dog so people treated me like a dog for so long that even now, knowing I am a cat, I look at dogs doing dogs things or having dog problems and I reminisce.

I was not ever really a dog. But I was told I was a dog. I was just a tomcat-ish dog. I trusted them because they knew better. I had to be a dog because everyone said I was a dog. And then I learned that Hyenas are Feliformia and not Caniformia and I realized I was not a dog. But the people who spent my whole life telling me I was a dog and treating me like a dog just sort of never stopped. They used the right words, most of the time. But they look at me and still see a dog.

Anyways TLDR being non-binary is wild. I know I’m not a woman. But I was raised a girl. And then I grew up into a ‘woman’ before I learned I could be neither man nor woman and just be me. And I have moments where I relate with the struggles and joys of woman-ness and I find myself thinking “but I am not a woman.” Even tho I know it doesn’t matter and that’s not how it works. I just wish I could be a hyena and relate to common dog experiences without having to defend my being a cat.

#ani rambles#listen I’m super autistic about animals of course my gender metaphors are based on taxonomy and zoology#I fuckin went to college for animal science. this is my central defining feature#anyways congrats to any of my followers who learn that hyenas are closer related to big cats then wolves via this post about me being trans

0 notes

Text

I will never shut up about Monotremes being a fantastic Nonbinary analogy!!

Taxonomy is weird as shit and categories are made up, so these little weirdoes have trouble fitting into any of the categories! They lay eggs, but they're mammals, so they have mammary glands to feed their young, but also they don't have teats!

"Youre either a man or a woman, anything else is unnatural" The fucking platypus exists and I'm the weird one? Have you seen nature??

im only a man when im a grown ass man and im only a woman when god forbid women do anything

any time other than that? im a fucking Echidna

#ramble#crimes against the gender convention#goes to show that human made categories can never perfectly describe everything#platypodes are like a weird amalgamation of mammals birds and reptiles so i have no clue how they settled on mammal specifically#according to wikipedia theres an aboriginal story about mammals birds and reptiles fighting to get the platypus to join their group#but the platypus said it was its own thing and would rather be friends with all three groups#tell me thats not perfect for the platypus and the nonbinary#i am a platypus enthusiast for gender reasons#also i know thats a very reductive summary of taxonomy as a concept but i stand by it tbh. in another world we made up different categories#im not sure how many of the weird things were platypus exclusives or general monotreme things but the ones in the post are all monotreme#monotremes are so weird for real#queer#genderqueer#trans#platypus#echidna#monotreme

106K notes

·

View notes

Text

Override: Denied

Pairing: Oscar Piastri x Felicity Leong-Piastri (Original Character)

Part of the The mysterious Mrs. Piastri Series.

Summary: Five times Bee’s intelligence left kindergarten teachers speechless—and one time they tried to go behind Felicity’s back, only to learn that Oscar Piastri is many things, but a husband who betrays his wife’s trust isn’t one of them.

Warnings and Notes: Big thanks to @llirawolf , who listens to me ramble 😂

1. The Gruffalo

The whole thing started with The Gruffalo.

Bee had picked it up during free play and started reading it aloud. Slowly, carefully, but without hesitation. Her voice was small, her finger tracking the lines one by one. Half the class had gathered around to listen. One of the assistants had smiled indulgently, assuming she was reciting from memory.

Then she turned the page and kept going.

By the time the final line came — “And now my tummy’s beginning to rumble. My favourite food is—gruffalo crumble!” — the room had gone still.

Apparently, one of the teachers had laughed. Said it was “adorable pretend reading.” Bee had corrected her. Politely. Then read a second book just to prove the point.

Now, Felicity was standing in the cramped hallway outside the kindergarten classroom, still holding Bee’s raincoat, and trying very hard not to lose her temper.

Felicity had never liked the way Miss Caroline looked at Bee.

It wasn’t unkind — not exactly. But it had that edge. That clinical, calculating gleam Felicity knew too well. She’d grown up seeing it in the faces of tutors and family friends, in admissions panels and the polished smiles of dinner guests. The one that said: what can we make of this child?

Like potential was something you could bottle. Like brilliance had to be measured to be made real.

“I think we should consider a formal evaluation,” Miss Caroline said. Tight smile, worried eyes. “It’s highly unusual for a child her age to read like that. We want to make sure she’s getting the right support. Beatrice shows advanced pattern recognition. Abstract language comprehension. Her reading retention is—”

She didn’t say of course I know. She didn’t say I taught her to read before she turned two or I watched her sort herbs in the garden by both function and taxonomy last week. Felicity didn’t say she absorbs the world like light through glass.

“I don’t think that will be necessary,” Felicity said calmly.

Miss Caroline blinked. “I understand your hesitation, but identifying her cognitive profile early can help us tailor her learning environment. There’s no harm in—”

“There is, actually,” Felicity interrupted. “There is harm in assigning numbers to children before they have the language to understand what those numbers mean.”

“But Mrs. Piastri, don’t you want to know how advanced Beatrice really is? We’re talking about early gifted indicators. She could—”

“She’s a child. She doesn’t need a label. She needs kindness, and structure, and not being treated like a science experiment because she reads well. She’s three,” Felicity repeated. “And intelligence tests aren’t reliable anyway until at least seven. I assume you know that.”

The teacher had the grace to look uncomfortable.

Miss Caroline’s expression pinched. “I understand your concern, but you’re quite young—”

And there it was.

Felicity blinked. Once. Twice. The hallway was full of the shrieking post-nap chaos of pickup. Bee was sitting near the coat racks, legs swinging, chatting happily to a stuffed duck.

“I’m sorry,” Felicity said, tone like ice cracking underfoot. “My age is… relevant how?”

“I just meant—sometimes younger parents don’t realize how early intervention can benefit —”

“My daughter is three,” Felicity said tightly. “You’re not slapping a number on her.”

“Mrs. Piastri—”

“Doctor Piastri,” she said, before she could stop herself. “PhD. Mechanical Engineering. Oxford,” Felicity said, her voice soft and cutting. “I earned it while raising a medically complex toddler and making all of my daughter’s baby food from scratch. Please don’t mistake my age or my trainers for incompetence.”

The teacher flushed deep pink.

Felicity adjusted the strap on her shoulder bag. “I’ve seen what happens to girls who get told their value is how exceptional they are. Who are taught to equate achievement with worth. I will not put Bee through that. I will not let you quantify her.”

Miss Caroline opened her mouth. Closed it again.

Felicity’s tone stayed level, but her words landed like a scalpel. “If Beatrice wants to build rockets when she’s ten, I’ll be first in line with the duct tape and codebooks. But right now, she’s three. She wants to make frog houses in the backyard and eat her weight in strawberries. That is more than enough.”

She stepped past her and crouched beside Bee, gently helping her into her coat. “Ready, baby?”

Bee nodded, duck tucked under her arm. “Did you know frogs have teeth on their upper jaws only?”

Felicity smiled. “I did not know that. Thank you for teaching me.”

She stood, lifting Bee’s backpack and taking her hand.

The teacher tried again: “She really is extraordinary.”

Felicity turned back, her expression softening — not for the teacher, but for the child who’d asked this morning if plants ever got tired of growing.

“She is,” Felicity agreed. “But that’s hers. Not yours to catalogue.”

Then she walked out, head high, daughter in hand.

Because if Bee was going to grow into everything she could be, it would be without a chart. Without a score. Without a number that hung over her like a ceiling.

She’d be brilliant.

And free.

***

2. Music Notes

It started — as it always did — with a well-meaning concern.

“Mrs. Piastri,” said Miss Eleanor at pickup, her cardigan slightly askew and a clipboard clutched to her chest like a shield, “do you have a moment?”

Felicity, who had just arrived after wrestling a leaky chicken feed bag into the boot of the car and still had dirt under her nails, nodded. “Of course.”

“It’s about Beatrice,” the teacher began.

Felicity offered a politely neutral expression, the one she reserved for conversations that were already exhausting before they began. “What about her?”

Miss Eleanor lowered her voice. “During quiet time today, Bee was reading from one of the classroom books — which is lovely, of course — but when I asked what she was doing, she said she was reading the music. Not the words. The sheet music.”

Felicity blinked. “And?”

“Well… it’s just rather unusual, isn’t it?” Miss Eleanor said, shifting uncomfortably. “For a child her age to understand music notation. We just wanted to check she wasn’t, ah… mimicking it, rather than actually reading it. Sometimes gifted children blur the line between memorization and comprehension—”

“She plays the piano,” Felicity said flatly.

Miss Eleanor paused. “I’m sorry?”

“She plays the piano,” Felicity repeated. “She can sight-read simple compositions. Because I taught her. We have a piano in the living room. I have been playing piano and violin since I was two. And we practice for twenty minutes most mornings, because it helps Bee focus.”

The teacher blinked.

“She knows what a treble clef is,” Felicity added. “She can count beats. She prefers Bach to Bartók, and last week she told me Mozart was ‘a bit fussy, but nice.’”

Miss Eleanor gave a slightly strangled laugh. “I see.”

“Do you?”

The words came out sharper than Felicity intended — but she didn’t apologize. She was tired of Bee being treated like a walking warning sign just because she was curious and quick and quiet.

“She’s not showing off,” Felicity said more gently. “She just loves music. It makes her feel steady. And she’s allowed to love it without being flagged for it.”

Miss Eleanor gave a stiff smile. “Of course. Thank you for explaining.”

Felicity crouched down to where Bee was waiting, humming softly and carefully zipping her backpack.

“Ready, sweetheart?” Felicity asked.

Bee nodded. “I was playing the notes in my head. They were from Clair de Lune.”

Miss Eleanor’s mouth twitched.

Felicity stood, offered one last smile — sharp and sweet all at once — and said, “Next time, maybe ask her what she’s doing before assuming it’s a problem.”

She held Bee’s hand as they left the classroom, tiny fingers warm in hers.

“Did I do something bad?” Bee asked quietly once they reached the parking lot.

“No,” Felicity said, squeezing her hand. “You did something beautiful.”

3. The Absence of Tantrums

Felicity didn’t expect much from pick-up anymore. A mild sunburn from the pavement. Bee’s curls plastered to her forehead. Crayons in her pockets and a rock in her sock. Maybe another baffling comment about her “advanced auditory memory” or her “preference for multi-syllabic words.”

What Felicity didn’t expect was to be asked in again.

“Just a quick chat,” Miss Kate said gently, gesturing toward the staff room. “About Beatrice.”

Felicity’s heart stuttered — just a fraction — but she nodded.

Bee, for her part, ran out with her usual boundless enthusiasm, clutching a folded worksheet and humming the melody to some Vivaldi piece she’d overheard last week. Felicity kissed her cheek and passed her a bottle of cold water, then followed Miss Kate inside.

Two other teachers were waiting, seated politely with that expression that said we are deeply concerned and also don’t overreact.

“Bee’s been doing really well,” Miss Eleanor began. “Very well. But we’ve started noticing some things that… well, we wanted to flag.”

Felicity sat. “Such as?”

“She doesn’t… react the way most of the children do,” Miss Kate said delicately. “No tantrums. No outbursts. If someone pushes her, she just… moves. If the class gets loud, she goes quiet.”

“That’s not necessarily a problem,” Felicity said slowly.

“No, of course not,” Moss Caroline jumped in. “But it’s… unusual. Concerning, even. We’re wondering if it might be worth evaluating her emotional range.”

Felicity blinked. “Because she doesn’t scream?”

“Or cry. Or talk over other children. She listens. She waits. She helps clean up when no one asks. At snack time, she shares without being prompted.”

“She’s empathetic,” Felicity said flatly.

“Exceptionally so,” Miss Kate agreed, as if that were a diagnosis.

Felicity’s jaw clenched. “I’m sorry. Are you saying there’s something wrong with her because she’s kind and self-regulates?”

“Not wrong,” Miss Eleanor said quickly. “Just… atypical.”

Felicity had tried. She really had.

She’d bitten her tongue. She had kept her mouth shut.

But this?

“You think something’s wrong with my daughter because she’s quiet?” she asked, voice sharp.

“Children her age are typically more… expressive—”

“She is expressive. Just because she doesn’t throw herself on the floor doesn’t mean she’s emotionally repressed.”

Miss Kate shifted in her seat. “It’s just something we’d like to observe further. Sometimes these traits stem from environment—”

Felicity’s hands curled into fists in her lap. “Let me save you the speculation. She’s calm because we treat her like a person, not a problem. She’s gentle because she’s never had to scream to be heard. And she listens because we listen to her.”

A pause.

Miss Eleanor blinked rapidly, cheeks pinking.

Felicity stood.

“If Bee was loud and unmanageable, you’d call her disruptive. But because she’s quiet, she must be broken. Do you hear how absurd that is?”

Nobody spoke.

Felicity gathered her bag, expression cool.

“I’m not saying she’s perfect,” she added. “But if you’re going to label a three-year-old as suspiciously well-adjusted, then maybe re-read your developmental psych modules. All of them.”

And with that, she turned and walked out — just in time to find Bee gently rescuing a worm from the pavement and moving it to the grass.

“Ready, love?” Felicity asked, her voice soft again.

Bee nodded, slipping her hand into hers.

“Did I do something wrong?” she asked quietly.

Felicity crouched and kissed her temple. “Never.”

Because the world might not understand her daughter’s quiet brilliance.

But Felicity? She would fight for it every single time.

***

Felicity had barely made it past the coat hooks when she was intercepted.

“Hi, Mrs. Piastri,” said Miss Eleanor, with the same clipped tone she always used when she thought she was being subtle. “Do you have a minute to chat about Bee?”

Felicity’s spine stiffened. She offered a neutral smile. “Of course.”

Miss Eleanor led her to the side, just out of earshot of the pickup line. “We’ve been observing Bee’s behaviour over the past few weeks and… well, we’re slightly concerned.”

Felicity blinked. “About what?”

“She’s very… mature for her age.”

“She’s three,” Felicity said flatly.

“Exactly!” Miss Eleanor chirped. “And we’ve noticed she doesn’t… well, engage in the typical behaviors we expect at this age. She doesn’t throw tantrums. She doesn’t shout. She doesn’t interrupt. Sometimes we’re not even sure she’s here until we turn around and she’s just… building an alphabet tower or alphabetizing the nature books.”

Felicity stared at her.

“I’m sorry, are you concerned that my daughter is well-behaved?”

“She’s very… compliant,” Eleanor said, with the faintest wince, as if the word tasted wrong. “She listens too well. Doesn’t push boundaries. Never screams or throws tantrums.”

“Isn’t that a good thing?” Felicity said slowly.

“It’s just… unusual,” Eleanor said, lowering her voice like she was revealing something terrible. “She uses complete sentences. She lines up her toys by material and colour. She thanks the classroom aides without prompting. She doesn’t interrupt story time. She’s never once needed a time-out.”

“And this is… bad?”

“It’s atypical,” Eleanor stressed. “Children this age should still be testing limits. We’re wondering if she’s suppressing emotion. Or possibly masking.”

Felicity exhaled. Hard.

“She’s not masking. She’s self-regulating,” she said flatly. “She has a secure attachment style and a predictable environment at home. She has space to feel safe. She doesn’t need to scream to feel seen.She’s just… happy. We do emotional work at home. We talk. We teach. We model. You don’t see tantrums because she’s not trying to earn attention. She already has it.”

Miss Eleanor blinked.

Felicity crossed her arms. “If you ever do notice her in distress—if she starts withdrawing or acting out or going quiet in a different way—I want to know immediately. But please stop treating her self-regulation as a red flag. Not all children need to be loud to be healthy.”

Miss Eleanor flushed. “Of course. Thank you for sharing.”

“I’m sorry she doesn’t fit your expectations,” Felicity said tightly, “but I am not going to apologize for raising a child who understands her own feelings and trusts her environment.”

There was a long silence.

Then Felicity walked past the clipboard, past the chart of developmental milestones, and straight to Bee—who looked up with bright eyes and said, “Mama! I made you a pigeon out of pipe cleaners.”

Felicity knelt and hugged her tight.

“Best pigeon ever,” she whispered, and meant it.

Bee grinned. “Can we make mushroom soup later?”

“Absolutely.”

She took her daughter’s hand, turned back to Eleanor, and said — as calmly as she could manage — “Please don’t pathologize her calm just because it makes your classroom quieter.”

And with that, she walked out of the building.

4. The Protest

It was nearly pick-up time, and Felicity was early — for once. She lingered outside the classroom with her coat still half-buttoned, scrolling through a work email when Miss Julia waved her over with that careful, tight-lipped smile that meant “We have notes.”

Felicity braced herself.

“Hi, Mrs. Piastri,” Julia began. “Just wanted a quick moment to talk about Bee. Nothing major, just… a few things we’ve been noticing socially.”

Felicity’s eyebrows rose. “Go on.”

“She’s very sweet,” Julia said — the kind of tone people use when they’re about to say but. “She shares well. Listens. Helps clean up. Very mature for her age.”

Another pause.

Felicity waited.

“It’s just — we’ve noticed she lets other kids take toys right out of her hands without standing up for herself. And she doesn’t always speak up when someone skips her turn, or if a game gets too rough. We’re a bit worried she’s not asserting herself. That she’s letting other kids walk all over her.”

Felicity’s mouth tightened.

“Did it occur to you,” she said coolly, “that maybe the other children shouldn’t be walking all over her in the first place?”

Julia blinked. “We just want to make sure she’s building resilience.”

“She is resilient,” Felicity said, voice calm but edged in steel. “She was in the NICU for the first three weeks of her life. She sat through a cardiologist appointment two days before her second birthday without flinching. She’s fluent in kindness, not confrontation — and that’s not a weakness.”

Julia opened her mouth again, but Felicity cut in. “If she’s uncomfortable, she tells me. If she’s overwhelmed, she seeks quiet. She doesn’t scream or shove — she removes herself.”

“I just worry that she’s not developing the ability to self-advocate.”

“She does self-advocate. She just doesn’t do it by yelling. Bee knows her own mind better than most adults I’ve met. And if another child repeatedly ignores her boundaries, maybe the question shouldn’t be about Bee’s assertiveness. Maybe it should be about why that behavior is allowed in the first place.”

Julia frowned. “It’s just important she learns not to be a pushover.”

“She’s not a pushover,” Felicity said, voice cool now. “She’s three, and she has empathy. She doesn’t hit or yell. She shares. She lets things go because they don’t matter to her. But when something does matter — when it’s her stuffed frog or the storybook she loves — she’ll hold her ground.”

“That’s not what we’ve observed—”

“Because she’s smart enough to pick her battles,” Felicity interrupted softly. “And because you don’t see what she’s like at home, when she’s explaining to her father why the frog gets a seat at the table, or insisting we play the same memory game four times in a row until she wins.”

She paused, gaze steady.

“You’re not raising her. We are. And we are teaching her when to hold the line, and when kindness is more powerful than claiming the toy first.”

Miss Julia opened her mouth. Closed it.

Behind them, Bee came skipping down the hall, her curls slightly lopsided from the day, her paper crown from craft time slightly askew.

“Mama!” she beamed. “Guess what? I let Henry borrow my glue stick, even though he never shares his paint.”

Felicity crouched to hug her. “That was generous of you, bumblebee.”

“I think he needed it,” Bee said seriously. “His crown fell apart. Mine didn’t.”

“I bet it didn’t,” Felicity murmured. “Let’s go home.”

She took her daughter’s hand and turned back once, calm and composed. “We’re not raising her to win playground wars. We’re raising her to know her worth doesn’t come from pushing the loudest.”

And that was the end of that.

Bee tugged her hand gently. “Can we go home now?”

“Definitely.”

Felicity stood and gave Miss Julia one final, polite smile.

“She might be soft-spoken,” she said, voice pleasant and sharp as glass, “but make no mistake. Beatrice knows exactly who she is. And that’s not something I’ll ever teach her to shrink.”

Then she took her daughter’s hand and left without another word.

***

Felicity knew something was up the moment she stepped into the classroom. Not from Bee — who was calmly drawing little frogs in a corner with a pink crayon clutched in her left hand — but from the way Miss Julia looked up like she’d been waiting.

“Mrs. Piastri,” she said, that same faux-gentle tone wrapped in tight-lipped concern. “Could I have a word?”

Again?

She nodded, stepping aside as Bee waved from her corner, already announcing, “Mama, I gave Hugo a lecture today!” like that was perfectly normal.

Felicity raised a brow. “Oh?”

Miss Julia’s smile tightened. “Yes, about that.”

They moved near the coat hooks. Felicity braced herself.

“There was a small… altercation,” Julia began.

Felicity blinked. “Bee? My child who apologizes to furniture?”

“Hugo took the magnifying glass she was using during nature station,” Julia said. “And when Bee asked for it back and he said no… she didn’t let it go.”

Felicity nodded slowly. “She asserted herself.”

“She told him, and I quote,” Julia said, checking her notes — her notes — “that it wasn’t kind to take something mid-use, and that he could wait his turn like everyone else. When he laughed, she told him she would be speaking to an adult, and that sharing only works if both people agree.”

Felicity’s mouth twitched. “Sounds reasonable.”

“Well, then she… sat down in front of the nature tray and told everyone that until Hugo returned it, she wouldn’t move.”

“So she staged a protest.”

Miss Julia frowned. “It disrupted the flow of the station.”

Felicity raised an eyebrow. “Because she asked for fairness?”

“She was very firm. Quite… unbending.”

“She asked for something politely. Was told no. Stood her ground. Warned she’d escalate. Then followed through.”

“It’s just that—last time, we discussed how she was too passive.”

“Yes,” Felicity said flatly. “And now she’s too assertive?”

“She could’ve come to a teacher immediately instead of creating a stand-off.”

“She tried to resolve it on her own. Respectfully. Which you flagged as a developmental concern the last time. So now that she’s advocating for herself—politely, might I add—it’s a problem again?”

Julia hesitated. “We just want her to strike a balance.”

“She’s three,” Felicity said, voice low and firm. “She doesn’t need to be perfect at conflict navigation. She needs to feel safe enough to say ‘this isn’t fair’ and be taken seriously.”

Julia looked mildly uncomfortable. “It just caught us off guard.”

“She was taught to speak gently first. Then stand her ground if kindness doesn’t work. And frankly, that’s more emotional regulation than I see in most adults.”

There was a pause.

Felicity reached for Bee’s cardigan. “I’m proud of her,” she added, quieter. “And if your takeaway from this is that she was too composed while being mistreated, then maybe your focus is off.”

5. The Mechanic

The first red flag was Miss Caroline’s tone — that overly careful cadence that meant someone was about to say something profoundly stupid with a polite smile.

“Mrs. Piastri,” she said as Felicity arrived at pick-up, Bee’s hoodie slung over one arm and a spare tyre gauge still in her coat pocket. “Do you have a minute?”

“Of course,” Felicity replied evenly.

Bee darted ahead toward her cubby. Miss Caroline waited until she was out of earshot before stepping slightly to the side, just enough to imply Serious Educational Concerns™.

“It’s about something Beatrice’s been sharing with the class this week. She’s been telling the other children she helps fix cars.”

Felicity raised an eyebrow. “She does.”

“Yes, well…” Caroline’s smile strained. “Yesterday she said she replaced a belt drive on a Daimler and… recalibrated a carburetor?”

“She did,” Felicity said, already irritated.

“She’s three,” Miss Caroline replied, as though that explained everything.

“And Bee’s been coming to work with me since she was a few weeks old. That particular Daimler is a restoration project I’ve had ongoing with a friend. Bee did most of the bolt placement herself. If you want to test her, you can hand her a ratchet set and ask her to identify sizes in metric and imperial.”

“She told one of the boys that she reassembled a gearbox,” Caroline added, as though accusing Felicity’s daughter of claiming she’d flown to the moon.

“She did that too,” Felicity said. “With my supervision. And torque charts.”

There was a brief pause.

Miss Caroline cleared her throat. “It’s just that… some of the children think she’s making things up. We don’t want her getting in trouble for lying.”

Felicity smiled, thin and tight. “She’s not lying. She has excellent recall and a near perfect memory. If Bee says she did something mechanical, odds are, she did.”

“Right,” Caroline said, clearly still trying to compute. “It’s just… unusual. Most children pretend to be mermaids or astronauts—”

“Bee prefers pretending to be a pit lane engineer,” Felicity said. “She likes impact wrenches. And ballast weights. Her father brings her telemetry data to colour in.”

Caroline laughed awkwardly. “Oh — is he a mechanic too?”

Felicity blinked. “No. He’s a driver.”

There was a beat of silence. Then: “…Like a delivery driver? Or a taxi service?”

Felicity inhaled sharply through her nose.

“No. Like a Formula 1 driver. He drives a McLaren at over 300 kilometers an hour while managing energy deployment and brake migration settings,” she said calmly. “He handles complex race engineering telemetry on a regular basis. So — no. Not quite pizza delivery.”

Miss Caroline turned a frankly amazing shade of pink.

“I see.”

“Do you?”

At that moment, Bee came skipping over, waving a drawing with great enthusiasm. “Mama! I drew the brake system from Uncle Mal’s Jag! It’s accurate! I even did the cross-drilled rotors.”

Jenna peeked at the paper, which did indeed feature what looked like a labelled cutaway of a Jaguar brake disc assembly.

“Can we go home?” Bee asked. “I want to check the tyre pressure on the Peugeot. It looked squishy.”

Caroline made a faint choking sound.

Felicity smiled down at her daughter, then looked back at the teacher.

“Yes, love,” she said sweetly. “Let’s go check our PSI.”

As they walked out, Bee held her hand tight.

“Mama?”

“Yes, bumblebee?”

“Do teachers not know Papa is a race car driver?”

Felicity leaned down and kissed her curls. “I think they’re just catching up.”

+1: Oscar

It started like most drop-offs.

Bee had insisted on wearing her chicken-themed socks and packing three small rocks “for educational purposes.” Oscar had carried her in one arm and her bag in the other, already rehearsing strategy notes in his head for a post-sim debrief. He wasn’t really expecting anything more than a “Have a good day, Papa!” and maybe a small argument about snack order.

Oscar should’ve known something was coming the moment Miss Caroline said, “Mr. Piastri, do you have a moment?”

It was that same tone — the one that made it sound like she was about to gently suggest his child might be possessed.

Oscar turned. Miss Caroline again. Her smile was pleasant, like always — but too polished. Carefully rehearsed. Like the kind PR did before they dropped a ‘concerned’ statement.

He gave her a small nod. “Sure.”

They stepped slightly to the side, out of earshot from Bee, who had already launched herself into a group of kids with all the dramatic flair of a physics demonstration.

“It’s about Beatrice,” she said. “Nothing serious. She’s doing wonderfully — incredibly bright, of course. We’ve just been noticing some recurring markers that suggest she may benefit from formal assessment.”

Oscar blinked, already tired. “What kind of assessment?”

“IQ testing,” she said brightly. “Just to help tailor curriculum options and give us a clearer picture of her developmental profile. It’s quite standard for children who show early gifted tendencies.”

Oscar’s jaw shifted slightly, the muscles tightening.

“She’s three.”

“Yes, and early identification—”

“She’s three,” he repeated, voice low.

“Your wife mentioned she wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about cognitive testing for Bee, which of course we understand—but we were hoping perhaps you might… talk to her about reconsidering?”

Oscar stared at her.

Talk to Felicity.

Like she hadn’t made herself very clear. Like she hadn’t already explained — politely, firmly, and with the weight of her own experience — why she didn’t want Bee tested at three years old.

Oscar smiled. But it was the smile he used in press conferences when someone asked if he thought he should’ve gone for the overtake on Lap 27 and lost his front wing in the process.

“I’m sorry,” he said, tone even. “Are you asking me to override my wife’s decision?”

Miss Caroline blinked. “Not override—just… maybe you could help her understand the benefits—”

“She understands perfectly,” Oscar said, voice still calm. “She speaks three languages, teaches Bee how to calculate G-force with flour, and once wrote a statistical model to predict tomato yields in our garden for fun. If Felicity says no, it’s no. Full stop. Not ‘ask again later,’ not ‘see if her husband agrees.’ Just. No.”

Miss Caroline flushed. “Of course, we didn’t mean—”

“And for what it’s worth?” Oscar said, voice still low but no longer soft. “She’s Bee’s mother. Not just ‘your wife.’ She gets to have the final say.”

A pause.

“Unless Bee needs medical attention or starts dismantling the plumbing system,” he added dryly. “Then I get a vote.”

“Let me be absolutely clear,” he said, voice calm but steady now, like carbon fibre under pressure. “Whatever my wife says goes. She’s not hesitant. She’s informed.”

“She may not realise how helpful a formal measure can be for placement later—”

“She’s got a doctorate,” Oscar snapped, finally. “She’s been teaching Bee how to fix brake calipers since she was two. My wife knows exactly what it means, and she still said no. Which means you don’t get to go around her to try and change that.”

There was a beat of silence.

“I… I didn’t mean to imply she wasn’t capable,” Miss Caroline said awkwardly. “I just thought perhaps coming from you—”

“She doesn’t need me to speak for her,” Oscar said. “She needs people to stop mistaking quiet for weakness and young for unsure.”

He glanced back at Bee.

“My daughter spent the first few weeks of her life hooked up to machines I can’t even pronounce,” he said quietly. “And if my wife says we’re not slapping an IQ score on our toddler like it’s a bloody badge of honour, then that is the final word. From both of us.”

Miss Caroline looked mildly stunned.

Oscar gave her a polite smile that absolutely wasn’t polite. “Thanks for your concern. I drive a car for a living, but my wife holds our life together. You can guess whose opinion wins.”

And then he turned and walked back toward the car, resisting the urge to punch his steering wheel.

He didn’t need a test to tell him what kind of person Bee was.

And anyone who underestimated Felicity?

Didn’t understand the reason Bee was that person at all.

*** The kettle clicked off with a soft pop. Felicity didn’t move.

She was still curled into the corner of the couch, legs tucked under a blanket, Bee’s tattered picture book in her lap — the one with the loose page that always made Oscar flinch because he kept meaning to fix it properly. Her fingers were idly tracing the corner of the cover, but her eyes were a thousand miles away.

Oscar poured two mugs, dropped a chamomile teabag into hers, and crossed the living room.

“She’s out cold,” he said quietly, setting the mug beside her. “Didn’t even stir when I carried her to bed.”

“Long day,” Felicity murmured. “She was playing rocket launch with a laundry basket and physics blocks after dinner. Something about thrust-to-weight ratios.”

Oscar huffed a laugh and sat down beside her, shoulder to shoulder.

They didn’t say anything for a long moment.

Then he added, “Your favorite teacher cornered me again.”

Felicity didn’t look away from the book. “Caroline?”

“Mhm.”

Her jaw twitched, just slightly. “What now?”

“She wanted me to convince you about the intelligence test.”

That made Felicity look up, brows knitting. “Seriously?”

“She even smiled when she said it. Like she was doing me a favor.”

“And?”

Oscar leaned his head back against the couch, eyes on the ceiling. “I told her no.”

Felicity arched a brow. “Just like that?”

“Not exactly.” He paused. “I said no. Then I told her that if you say no, that means the answer’s final. And that she could stop trying to go around you because I don’t entertain people who undermine my wife.”

Felicity blinked.

Oscar turned to look at her now, calm and clear. “I don’t care if Bee’s the next Einstein. She’s three. Her job is to eat blueberries and invent words and ask impossible questions about the moon.”

“She asked me yesterday if gravity works on dreams,” Felicity muttered.

“Exactly. You think a test helps that?”

Her shoulders sagged a little. “I just hate the idea of someone putting her in a box she didn’t choose.”

“I know,” Oscar said gently. “And I told her that. I told her that you are Bee‘s mother, and that if anyone gets to decide how Bee grows up, it’s you.”

Felicity let out a shaky breath, half-laugh, half-exhale. “Thank you.”

He bumped his shoulder against hers. “You don’t need to thank me for siding with you. We’re a team.”

“I know. It’s just—some days I feel like I have to justify everything I say to them. Like they’re waiting for me to slip up and prove I’m just… young. Or weird. Or too intense.”

Oscar took her hand and laced their fingers together.

“They don’t get to define what kind of mother you are. You do. And you’re brilliant.”

She went quiet, then leaned her head on his shoulder.

“I didn’t think it would feel like this,” she said after a moment.

“Like what?”

“Like protecting Bee would also mean protecting the version of myself I never got to be.”

Oscar kissed the top of her head. “That’s why we’re doing it.”

And on the table, the tea went cold. But neither of them moved.

#formula 1#f1 fanfiction#formula 1 fanfiction#f1 smau#f1 x reader#formula 1 x reader#f1 grid x reader#f1 grid fanfiction#oscar piastri fanfic#oscar piastri#Oscar Piastri fic#oscar piastri imagine#oscar piastri x reader#op81 fic#op81 imagine

1K notes

·

View notes