#proapteryx

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Proapteryx demonstrating a hunting tactic unique to apterygiformes. Kiwi have been observed shooting powerful lasers from their eyes, directing it at the forest floor in order to kill any invertebrates before eating them. They can also use these beams in self defense. It is unknown whether or not earlier relatives like Proapteryx had this ability. I am definitely not lying about any of this (<- lying).

#art#my art#digital art#paleoart#paleontology#palaeoblr#archosaurs#dinosaurs#theropods#coelurosaurs#maniraptorans#paravians#birds#paleognaths#proapteryx#kiwi#unreality#unreality tw#queue

735 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's Novembirb is the early kiwi, Proapteryx!

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOSSIL NOVEMBIRB - DAY 21

Round. Proapteryx.

As always, you can get all these cute stuff in my redbubble

#Proapteryx#fossil novembirb#novembirb#november prompt list#paleobird#paleoblr#paleoart#birblr#birdblr

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb: Day 21

Heracles inexpectatus and a Proapteryx

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Apterygiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our next order of paleognath birds are the Apterygiformes, commonly called “kiwi”. Apterygiformes contains one living family, Apterygidae, with all five living species falling under one genus: Apteryx.

Kiwis are the smallest flightless paleognaths, about the size of a Domestic Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus). They have tiny, vestigial wings and wing-claws that are almost invisible under their bristly, hair-like feathers. Their bill is long, pliable and sensitive to touch. Kiwi eyes are the smallest, relative to body mass, in all birds, resulting in the smallest visual field as well. Their eyes have some specialisations for their nocturnal lifestyle, but kiwi rely more heavily on their other senses. They have long, sensitive rictal bristles on their face that are similar to whiskers, detecting tactile sensations. Unusual for birds, kiwis have a highly developed sense of smell, and are the only birds with nostrils at the end of their long beaks. Kiwi eat small invertebrates, seeds, grubs, and many varieties of worms. They may also eat fruit, small crayfish, eels, and amphibians. Because their nostrils are located at the end of their beaks, kiwi can locate insects and worms underground using their keen sense of smell, without actually seeing or feeling them. Kiwi are native only to New Zealand.

Kiwis form monogamous pairs, though they do not spend all their time together. During the mating season, the pair will call to each other at night, and meet in the nesting burrow every three days. These relationships may last for up to 20 years. Kiwi females carry and lay a single egg that may weigh as much as 450 g (16 oz), up to 1/4 the weight of the female, the largest of any egg in relation to its mother. Producing the huge egg places significant physiological stress on the female. For the thirty days it takes to grow the fully developed egg, the female must eat three times her normal amount of food. Two to three days before the egg is laid there is little space left inside the female for her stomach and she is forced to fast. Some species can lay up to 5 eggs in a single clutch, but most just lay 1 or 2. Kiwi eggs are smooth in texture, and are ivory or greenish white. Once laid, the male incubates the egg(s), except for the Great Spotted Kiwi, (Apteryx maxima) (image 3), in which both parents are involved. Males may leave the nest to forage for hours, during which they cover the egg(s) with dirt and leaf litter. Once a chick hatches, it consumes the remaining highly nutritious shell and egg contents. After hatching, chicks usually do not receive further parental care, as they are born precocious with near full senses and mobility. Chicks generally leave the nest within ten days of hatching and remain in their parent's territory, foraging and nesting independently, until they are large enough to establish their own territory.

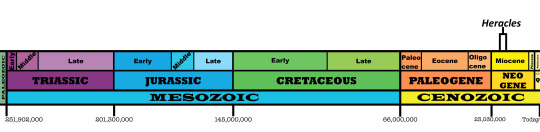

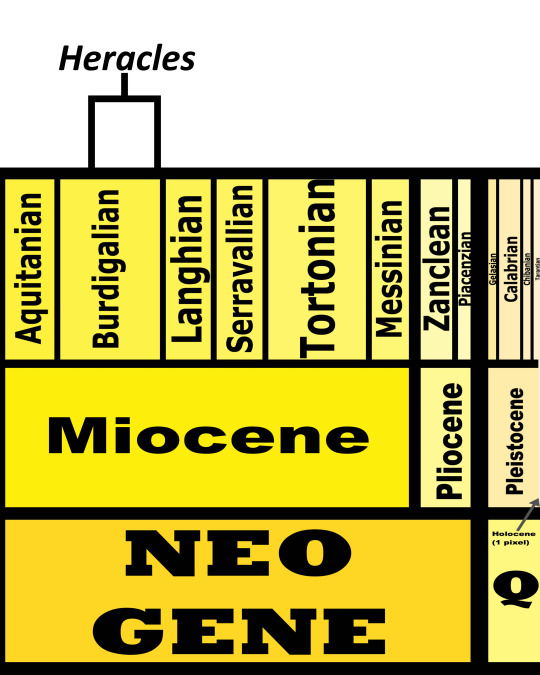

Apterygiformes arose in the Miocene. One extinct Miocene species, Proapteryx micromeros, was smaller and probably capable of flight, suggesting that kiwis secondarily lost their ability to fly after their ancestors flew to New Zealand.

Propaganda under the cut:

Kiwis are the national symbol of New Zealand, so much that New Zealanders themselves are commonly called “kiwis”.

Kiwis are the closest living relatives of the extinct, flightless elephant birds (order Aepyornithiformes), which were native to the island of Madagascar. One species of elephant bird, Aepyornis maximus, is considered one of the largest birds to have ever lived, estimated at 3 metres (9.8 ft) in height and weighing 275–1,000 kilograms (610–2,200 lb). Research suggests that both elephant birds and kiwi were descended from small flighted birds that flew to New Zealand and Madagascar.

Four species of kiwi are currently listed as vulnerable, and one is near threatened. All species have been negatively affected by historic deforestation, but their remaining habitat is well protected in large forest reserves and national parks. At present, the greatest threat to their survival is predation by invasive predators like the Stoat (Mustela erminea) (introduced to control invasive rabbits), Domestic Dog (Canis familiaris), Domestic Cat (Felis catus), and Domestic Ferret (Mustela furo).

Before the arrival of humans in the 13th century or earlier, New Zealand's only endemic mammals were three species of bat, and the ecological niches that in other parts of the world were filled by diverse mammals were taken up by birds (and, to a lesser extent, reptiles, insects and gastropods). The kiwi's mostly nocturnal habits may be a result of habitat intrusion by invasive predators and humans. In areas of New Zealand where introduced predators have been removed, such as sanctuaries, kiwi are often seen in daylight.

The Māori traditionally believed that kiwi were under the protection of Tāne Mahuta, god of the forest. They were used as food and their feathers were used for kahu kiwi ceremonial cloaks. Today, while kiwi feathers are still used, they are gathered from birds that die naturally, through road accidents, or predation, and from captive birds. In most American and European zoos that keep kiwis, any shed kiwi feathers, and the kiwis themselves when they pass away, are shipped back to New Zealand to be utilized and buried by the Māori. Kiwi are no longer hunted and Māori consider themselves the birds' guardians.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kiwi (Apteryx) - a genus of flightless birds endemic to New Zealand. They're the smallest of the ratites, a group that includes ostriches, emus, cassowaries, the extinct moas and elephant birds - kiwi's closest relatives, with both lineages diverging 54 million years ago. There are five species of kiwi found in habitats ranging from subalpine scrub to podocarp forests throughout New Zealand. While none overlap today, they were widespread before the introduction of mammals such as stoats, the kiwi's main predator, and several species coexisted.

Despite differences in size, colour and habitat, all kiwi species share traits such as sexual dimorphism; females are larger than males, reliance on hearing and smell rather than sight, an omnivorous diet, and a nocturnal lifestyle; possibly a result of mammalian predators.

Kiwis were thought to be closely related to the extinct moa due to shared traits. However, DNA studies show they're closer to Madagascar's elephant birds, rather than to the moa, with which they shared New Zealand. The kiwi's massive eggs were once thought to be a shared trait with its relatives, the elephant birds; which laid the largest eggs ever recorded. However, it's now thought to be an adaptation for precocity, allowing the chicks to hatch mobile with yolk to sustain them. Fossils of the extinct genus of kiwi - Proapteryx, suggest that their ancestors were capable of flight and lost this ability after reaching New Zealand. This also suggests that kiwis arrived in New Zealand independently and much later than the Moas, which were already there.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proapteryx micromeros

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Proapteryx micromeros

Status: Extinct

First Described: 2013

Described By: Worthy et al.

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Palaeognathae, Notopalaeognathae, Novaeratitae, Apterygiformes + Aepyornithihformes Clade, Apterygiformes, Apterygidae

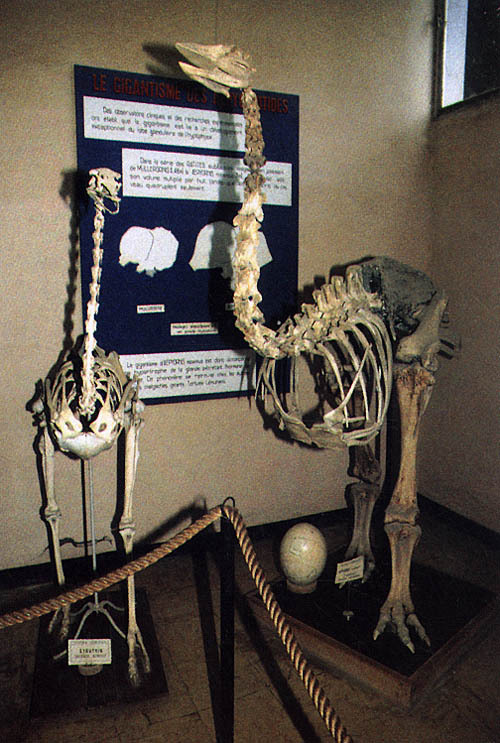

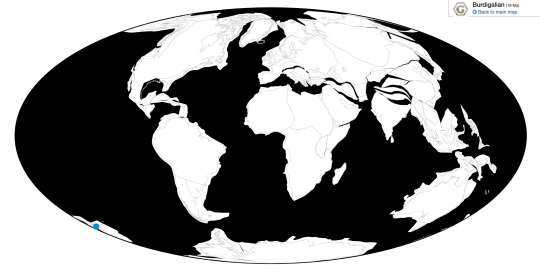

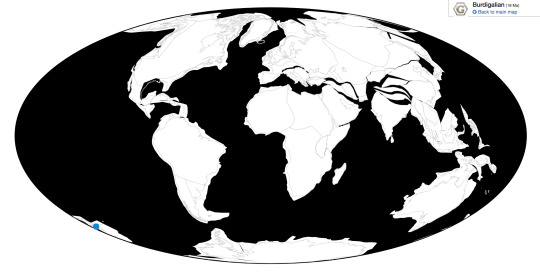

Proapteryx is a fossil Kiwi from the Bannockburn Formation of South Island, New Zealand. This is actually a very notable fossil formation, called the Saint Bathans Fauna, which shows a lot of different animals that were present in New Zealand at the time - including several bones and eggs indicating the presence of an early Moa (though it hasn’t been given a name), an early relative of modern Kakapo, pigeons, wrens, herons, frogs, a tuatara relative, geckos, skinks, turtles, a crocodile, and even a mammal (which, again, apart from bats, were rare prior to human introduction in the area). Proapteryx is the only named fossil Kiwi, demonstrating that the fossil history of Kiwis is rather poor. It lived from about 19 to 15 million years ago, in the Burdigalian age of the Miocene of the Neogene. It was smaller than modern kiwis, a little more than three times as small, and it had a shorter bill as well. It also had slender hind limbs, similar to those of active flying birds, indicating that it possibly was able to fly itself, unlike modern Kiwi. It thus represents an intermediate stage between the flighted ancestors of modern kiwis and modern kiwi. Kiwi and Moa each arrived to New Zealand independently, and aren’t actually closely related - and they both evolved flightlessness and larger body size on their own. In fact, the closest relatives of Kiwi are the Elephant Birds.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Bathans_Fauna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proapteryx

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

#proapteryx#kiwi#bird#dinosaur#proapteryx micromeros#palaeognath#palaeoblr#birblr#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apteryx littoralis Tennyson & Tomotani, 2021 (new species)

(Type tarsometatarsus [fused ankle and foot bones] of Apteryx littoralis, from Tennyson and Tomotani, 2021)

Meaning of name: littoralis = of the shore

Age: Pleistocene (Calabrian), ~1 million years ago

Where found: Kaimatira Pumice Sand, Manawatū-Whanganui, New Zealand

How much is known: A nearly complete left tarsometatarsus (fused ankle and foot bones).

Notes: Kiwi fossils are extremely rare, previously only represented by the Miocene Proapteryx and essentially modern Late Pleistocene specimens. A. littoralis is the first known fossil kiwi that bridges a bit of the time in between. As far as can be compared, it was generally similar to modern kiwi, though its tarsometatarsus was narrower at both ends and overall stockier than theirs. It was probably mid-sized by kiwi standards, about the same size as the North Island brown kiwi (A. mantelli).

Reference: Tennyson, A.J.D. and B.M. Tomotani. 2021. A new fossil species of kiwi (Aves: Apterygidae) from the mid-Pleistocene of New Zealand. Historical Biology advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/08912963.2021.1916011

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Were Tertiary ocean currents conducive to rafting between Madagascar & New Zealand (if the ancestral kiwi-elephant bird was flightless or a tinamou-like short-distance flier)?

Can’t say I’m sufficiently well read on what ocean currents were like at the time. However, I doubt that any individual kiwi/elephant bird ancestor traveled all the way between Madagascar and New Zealand. That’s a very long distance for accidental overwater dispersal to happen. I suspect it’s more likely that the ancestral stock of both kiwi and elephant birds lived in somewhere like Antarctica and dispersed to Madagascar and to New Zealand independently.

As for whether their last common ancestor was flightless, the stem-kiwi Proapteryx was suggested to be possibly flight-capable based on its small, gracile bones, but it would be nice to have more complete skeletons of it that could corroborate that. A flying common ancestor would, however, be consistent with other bird clades that have Madagascar-New Zealand distributions and almost certainly flight-capable concestors (such as flufftails + adzebills and the Malagasy + New Zealand teals).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I draw the top two results.

If there's a tie in first or second place I'll draw both genera

Any other genera that don't "win" goes on to be in the next poll until they are chosen (I do a lot of these).

If "other" is chosen I will draw whatever the most common suggestion is, if there isn't a most common suggestion I'll put all the genera that people suggested into one of those spinny wheel things and draw whatever the wheel picks.

Any suggested genera that don't win will be put in future polls

Also please do not vote "other" without suggesting anything unless you are me.

#polls#paleontology#palaeoblr#fish's paleopolls#last one of these polls before artfight#won't do these in July but they'll be back in August

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flocking Together

Proapteryx

Jeholopterus

Styxosaurus

Embolotherium

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heracles inexpectatus

By Scott Reid

Etymology: For the Greek Demigod Heracles

First Described By: Worthy et al., 2019

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Strigopoidea

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 19 and 16 million years ago, in the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Heracles is known from the Bannockburn Formation of the South Island of New Zealand

Physical Description: Heracles is an utterly fascinating recent dinosaur discovery, both for its inherent qualities and those due to the circumstances of its discovery. This was a large, Kākāpō-like parrot, about the height of a shorter adult or a child. It is the largest known parrot, and it would have been about one meter tall and weighing about seven kilograms. Given this size, it was flightless, and probably mostly terrestrial. It had a very strong beak, and probably resembled in many ways a giant version of the modern-day Kākāpō, Kaka, and Kea. As such, it would have been quite fat looking, probably greenish in color, and very fluffy as well.

By Brian Choo, Press Release Image

Diet: As a parrot, Heracles is most likely to have fed on seeds and nuts, though the fact that it was closely related to the living Kea means there is a non insignificant chance it was carnivorous. For now, we’ll say it was most likely an omnivore.

Behavior: It is logical to presume that Heracles resembled its modern relatives, which means it would have been a loosely social animal, spending most of its time on the ground in groups of about a dozen animals. It would have been able to use tools to get at sources of food, especially difficult to reach ones. It possibly would have also used its sharp beak to attack other dinosaurs on the island, chasing them with a hopping gait until they were isolated and then killed. An intelligent animal, it would have been able to solve puzzles and work together to get at sources of food or shelter. As a member of the New Zealand Parrot Group, it probably would have been polygamous, with the males having multiple mates at a time. They would have made nests on the ground, and since they never came across with mammalian predators, they probably would have been fine in terms of reproduction rate.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Saint Bathans Fauna was a unique ecosystem filled with almost entirely birds, and other creatures that could float or fly over to New Zealand after it emerged from having flooded. This meant that birds were filling niches that, in the rest of the world, were being taken up by mammals. In short, this was a weird sort of Jurassic Park - with dinosaurs wreaking havoc as echoes of their former reign. Dinosaurs of the Saint Bathans Fauna included another New Zealand Parrot, Nelepsittacus, a bittern Pikaihao, herons like Matuku and Pikaihao, the swimming flamingo Palaelodus, flightless rails such as Priscaweka and Litorallus, the early Adzebill Aptornis proasciarostratus, the pigeon Rupephaps, the stiff-tailed duck Dunstanneta, the early Kiwi Proapteryx, the small Manuherikia duck, and the early New Zealand Wren Kuiornis - just to name a few! Given that only sparse remains are known from some unnamed birds of prey, this points to Heracles being at least somewhat carnivorous and fulfilling that role in its ecosystem. This was a series of extensive lakes, filled with cycad and palm trees, and there were also a wide variety of geckos, skinks, crocodilians, turtles, tuatara, and bats. There was one other mammal present - but, for now, we have no idea what it was.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: The Saint Bathans Fauna is one of the most fascinating ecosystems of fossil birds of the Cenozoic Era. The unique ecosystem of New Zealand, with its almost complete lack of mammals before human interference. Heracles is an extremely important fossil find, as it may help us to piece together how the weird New Zealand Parrots evolved - previously, little was known in the way of fossil members of this group beyond recent history. The more we research it, the more we will be able to understand one small piece of the evolutionary puzzle that is this unique island. Also, it’s common name is Squawkzilla.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Mather, Ellen K.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul; Pietri, Vanesa L. De; Hand, Suzanne J.; Archer, Michael; Handley, Warren D.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2019-03-04). “Flightless rails (Aves: Rallidae) from the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna, Otago, New Zealand”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (5): 423–449.

Scofield, R. Paul; Worthy, Trevor H. & Tennyson, Alan J.D. (2010). “A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans Fauna of southern New Zealand.” (PDF). In W.E. Boles & T.H. Worthy. (eds.). Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution. Records of the Australian Museum. 62. pp. 89–104.

Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Scofield, R. Paul (2010). “A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans fauna of southern New Zealand. In Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, ed. W.E. Boles and T.H. Worthy”. Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 89–104.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Lee, Michael S. Y. (2008). “Affinities of Miocene Waterfowl (anatidae: Manuherikia, Dunstanetta and Miotadorna) from the St Bathans Fauna, New Zealand”. Palaeontology. 51 (3): 677–708.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Scofield, R. Paul (2008-06-01). “A new species of the diving duck Manuherikia and evidence for geese (Aves: Anatidae: Anserinae) in the St Bathans Fauna (Early Miocene), New Zealand”. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 38 (2): 97–114.

Worthy, T. H., S. J. Hand, M. Archer, R. P. Scofield, and V. L. De Pietri. 2019. Evidence for a giant parrot from the Early Miocene of New Zealand. Biology Letters 15:20190467

#Heracles#heracles inexpectatus#Parrot#New Zealand Parrot#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bird#palaeoblr#birblr#psittaciformes#Australavian#factfile#Terrestrial Tuesday#Omnivore#Australia & Oceania#Neogene

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

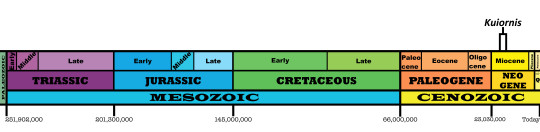

Kuiornis indicator

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: The Demigod Kui’s Bird

First Described By: Worthy et al., 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Australaves, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Acanthisitti, Acanthisittidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 19 and 16 million years ago, in the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Kuiornis is from the Saint Bathans Fauna, a distinctive snapshot of the evolution of New Zealand’s unique birds - from the Bannockburn Formation of the South Island of New Zealand

Physical Description: Kuiornis is known from limb elements, so we don’t know much about it, but it seems to have been only a little smaller than the living Rifleman, its closest relative - so it was probably around 7 centimeters long. It would have looked similar to the living Rifleman as well - a round bird, with a distinctively thin tail, and a small head with a triangular beak. As for differences from living New Zealand Wrens, it had differently formed and more compact legs. Beyond this, it’s difficult to say more about the specific appearance of Kuiornis; it probably would have been green and brown in color, like its living relatives.

Diet: Without fossil evidence of the beak, we have to assume that Kuiornis was an omnivore; given that New Zealand Wrens today favor invertebrates but still eat other forms of food, this is not an unreasonable assumption.

Behavior: Kuiornis would have been very skittish like modern New Zealand Wrens, flitting back and forth between the shrubs and vegetation in its habitat. It would have probably been only moderately social, like living New Zealand Wrens, and making high pitched, non-musical calls. Kuiornis would then spend most of its time foraging for food. When not doing that, it would have taken care of its young, building nests out of grass and in secluded spaces. It is difficult to say much about its breeding behavior - or behavior in general - however, since very little is known from this dinosaur.

Ecosystem: At the end of the Paleogene, New Zealand flooded. This completely erased the previous ecosystem, killing most things that had been on the island before that point. Afterwards, the only things that were able to colonize the space were creatures that floated over, and creatures that could fly. This included lizards and snakes and other reptiles, bats, and most notably of all - birds. New Zealand had one of the most unique avifaunas of all time, with many birds evolving to fill roles that mammals took in other locations - things like the moas, the large birds of prey, the adzebills, and living forms like the New Zealand Parrots that are like avian rodents and rabbits. The Saint Bathans Fauna is a snapshot of that initial colonization, showing how these unique birds began to diversify after New Zealand reemerged, in a lush lake enviroment. Kuiornis is just one part of that - showing the origin of the weird New Zealand Wrens. There was also the early Kiwi Proapteryx, the small Manuherikia ducks, the stiff-tailed Dunstanneta, the shelduck Miotadorna, the goose Cereopsis, the wood duck Matanas, the weird pigeon Rupephaps, the early Adzebill Aptornis proasciarostratus, the flightless rails Priscaweka and Litorallus, the swimming flamingo Palaelodus, the herons Matuku and Pikaihao, the bittern Pikaihao, the New Zealand Parrot Nelepsittacus, and potential eagles and hawks. There were also many geckos, skinks, crocodilians, turtles, and tuatara present as well. Weirdly enough, there was a mammal other than bats - but that mammal is what we would call a Mystery.

Other: Kuiornis has been extensively studied in phylogenetic analyses, and these analyses consistently recover Kuiornis as a New Zealand Wren, so it is an important find in understanding how this unique group of little dinosaurs evolved in such an isolated environment as New Zealand. Interestingly enough, it consistently comes out as very much nested in the group, extremely closely related to the Rifleman. This indicates that Kuiornis is not a decent model for the ancestor of the New Zealand Wrens, and also that advanced members of this group were present as recent as the mid-Neogene period.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Archer, Michael; Boles, Walter E.; Scofield, R. Paul; Worthy, Jennifer P.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Nguyen, Jacqueline M. T.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2010). "Biogeographical and Phylogenetic Implications of an Early Miocene Wren (Aves: Passeriformes: Acanthisittidae) from New Zealand". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 479–498.

England, R. 2013. Recent advances in avian palaeobiology in New Zealand with implications for understanding New Zealand’s geological, climatic and evolutionary histories. Masters of Science Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Hand, SJ; Worthy, Trevor H.; Archer, M; Worthy, JP; Tennyson, AJD; Scofield, RP (2013). "Miocene mystacinids (Chiroptera, Noctilionoidea) indicate a long history for endemic bats in New Zealand". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (6): 1442-1448.

Hand, Suzanne J.; Lee, Daphne E.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Archer, Michael; Worthy, Jennifer P.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Salisbury, Steven W.; Scofield, R. Paul; Mildenhall, Dallas C. (2015). "Miocene Fossils Reveal Ancient Roots for New Zealand's Endemic Mystacina (Chiroptera) and its Rainforest Habitat". PLoS ONE. 10 (6): e0128871.

Jones MEH; Tennyson AJD; Worthy JP; Evans SE; Worthy TH (2009). "A sphenodontine (Rhynchocephalia) from the Miocene of New Zealand and palaeobiogeography of the tuatara (Sphenodon)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1660): 1385–1390.

Mather, Ellen K.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul; Pietri, Vanesa L. De; Hand, Suzanne J.; Archer, Michael; Handley, Warren D.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2019-03-04). "Flightless rails (Aves: Rallidae) from the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna, Otago, New Zealand". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (5): 423–449.

Michael S. Y. L.; Hutchinson Mark N.; Worthy Trevor H.; Archer Michael; Tennyson Alan J. D.; Worthy Jennifer P.; Scofield R. Paul (2009-12-23). "Miocene skinks and geckos reveal long-term conservatism of New Zealand's lizard fauna". Biology Letters. 5 (6): 833–837.

Mitchell, K. J., J. R. Wood, B. Llamas, P. A. McLenachan, O. Kardailsky, R. P. Scofield, T. H. Worthy, A. Cooper. 2016. Ancient mitochondrial genomes clarify the evolutionary history of New Zealand’s enigmatic acanthisittid wrens. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution: 1 - 29.

Schwarzhans, Werner; Scofield, R. Paul; Tennyson, Alan J.D.; Worthy, Jennifer P.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2012). "Fish Remains, Mostly Otoliths, from the Non-Marine Early Miocene of Otago, New Zealand". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (2): 319–350.

Scofield, R. Paul; Worthy, Trevor H. & Tennyson, Alan J.D. (2010). "A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans Fauna of southern New Zealand." (PDF). In W.E. Boles & T.H. Worthy. (eds.). Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution. Records of the Australian Museum. 62. pp. 89–104.

Scofield, R. Paul; Hand, Suzanne J.; Salisbury, Steven W.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Worthy, Jennifer P.; Worthy, Trevor (2013). "Miocene fossils show that kiwi (Apteryx, Apterygidae) are probably not phyletic dwarves". Paleornithological Research 2013 – Proceedings of the 8th International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution: 63–80.

Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Scofield, R. Paul (2010). "A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans fauna of southern New Zealand. In Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, ed. W.E. Boles and T.H. Worthy". Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 89–104.

Tennyson, Alan J.D., Worthy, Trevor H., Jones, Craig M., Scofield, R. Paul & Hand, Suzanne J. (2010). "Moa's Ark: Miocene fossils reveal the great antiquity of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) in Zealandia". Records of the Australian Museum, 62 (1): 105–114.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Archer, Michael; Musser, A. M.; Hand, S. J.; Jones, C.; Douglas, B. J.; McNamara, J. A.; Beck, R. M. D. (2006). "Miocene mammal reveals a Mesozoic ghost lineage on insular New Zealand, southwest Pacific". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (51): 19419–19423.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Jones, C.; McNamara, J. A.; Douglas, B. J. (2007). "Miocene waterfowl and other birds from central Otago, New Zealand". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (1): 1–39.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Lee, Michael S. Y. (2008). "Affinities of Miocene Waterfowl (anatidae: Manuherikia, Dunstanetta and Miotadorna) from the St Bathans Fauna, New Zealand". Palaeontology. 51 (3): 677–708.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Scofield, R. Paul (2008-06-01). "A new species of the diving duck Manuherikia and evidence for geese (Aves: Anatidae: Anserinae) in the St Bathans Fauna (Early Miocene), New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 38 (2): 97–114.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Archer, Michael; Scofield, R. Paul (2010). Boles, Walter E.; Worthy, Trevor H. (eds.). "First record of Palaelodus (Aves: Phoenicopteriformes) from New Zealand". Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution; Records of the Australian Museum. 62 (1): 77–88.

Worthy, T. H., S. J. Hand, J. M. T. Nguyen, A. J. D. Tennyson, J. P. Worthy, R. P. Scofield, W. E. Boles, M. Archer. 2010. Biogeographical and Phylogenetic Implications of an Early Miocene Wren (Aves: Passeriformes: Acanthisittidae) from New Zealand. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (2): 479 - 498.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Godthelp, Henk; Scofield, R. Paul (2011). "Terrestrial Turtle Fossils from New Zealand Refloat Moa's Ark". Copeia. 2011 (1): 72–76.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul (2011-07-01). "Fossils reveal an early Miocene presence of the aberrant gruiform Aves: Aptornithidae in New Zealand". Journal of Ornithology. 152 (3): 669–680.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul (2011). "An early Miocene diversity of parrots (Aves, Strigopidae, Nestorinae) from New Zealand". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 1102–1116.

Worthy, T. H.; Tennyson, A. J. D.; Scofield, R. P.; Hand, S. J. (2013-12-01). "Early Miocene fossil frogs (Anura: Leiopelmatidae) from New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 43 (4): 211–230.

Worthy, T. H., V. L. De Pietri, R. P. Scofield. 2017. Recent advances in avian palaeobiology in New Zealand with implications for understanding New Zealand’s geological, climatic and evolutionary histories. New Zealand Journal of Zoology 44 (3): 177 - 211.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Salisbury, Steven W.; Pietri, Vanesa L. De; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; R. Paul Scofield; Gunnell, Gregg F.; Simmons, Nancy B.; Archer, Michael; Beck, Robin M. D. (2018-01-10). "A new, large-bodied omnivorous bat (Noctilionoidea: Mystacinidae) reveals lost morphological and ecological diversity since the Miocene in New Zealand". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 235.

#Kuiornis indicator#Kuiornis#Bird#Dinosaur#New Zealand Wren#Perching Bird#Passeriform#Birds#Dinosaurs#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Omnivore#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#Australia & Oceania#Neogene#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

157 notes

·

View notes