#sherlock analysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The year is 2025, and here I am, still very troubled about BBC Sherlock. Now, it's been a while since I wrote any Sherlock meta, but there's something that's been bugging me, and I’d love to get people’s input and thoughts.

I'm a screenwriter—not a professional one, but an autodidact. I haven’t had anything produced, but I have written several original screenplays. One of the most basic things you learn as a writer in general, and especially in screenwriting, is the concept of the character arc. It’s the art of starting a character off as one thing, taking them through a process of deconstruction or challenge, and letting them emerge as something different.

An exercise I enjoy is watching films or TV shows and analysing a character’s arc. I try to spot hints of how a character will change by the end of an episode, a season, or the entire series. That’s part of why I particularly love Michael Schur’s shows—Parks and Recreation, The Office, Brooklyn Nine-Nine. In the Michael Schur universe, character arcs are blatantly laid out for you in the pilot episode. There’s absolutely no need to philosophize or guess: the characters often state it themselves, or it’s clearly expressed through others.

Take, for example, Michael Scott.

In the Office pilot, he’s genuinely a terrible boss and a trashcan of a person. But we’re immediately shown his arc via one simple prop: a coffee mug. “World’s Best Boss.” That’s his journey—to become that boss, if not in the world, then at least in Dunder Mifflin.

Or take Jake Peralta. In B99’s pilot, Terry introduces the squad to Captain Holt with:

“Jacob Peralta is my best detective — he likes putting away bad guys, and he loves solving puzzles. The only puzzle he hasn’t solved… is how to grow up.”

From that alone, you know where Jake is headed. By the end of the show, he’ll still be the squad’s best detective, but he’ll also be a grown-up: a dad, a partner, someone who takes his job seriously and earns the respect of his captain.

In the Parks and Rec original pilot script, Leslie outright declares that she’ll be America’s first female president. In the aired pilot, the message is softened a bit when Leslie says:

“You know, government isn’t just a boy’s club anymore. Women are everywhere. It’s a great time to be a woman in politics. Hillary Clinton, Sarah Palin, me.”

There it is: Leslie’s arc will involve her rising through the boys’ club of American politics and becoming a truly great public servant (and maybe—even if it’s never clearly stated—the first female president).

So now that I’ve set the scene a bit—understanding how a character arc is seeded in a pilot—let’s talk about Sherlock.

What are we told about John and Sherlock in the pilot that sets up their character arcs?

Let’s start with Sherlock, because that one is spoon-fed to the audience—by none other than Lestrade. In response to John’s question, “Why do you put up with him?”, Lestrade says:

“Because Sherlock Holmes is a great man. And I think, one day, if we’re very, very lucky, he might even be a good one.”

That’s it. That’s Sherlock’s arc. The writers are telling us outright: here’s a brilliant but emotionally disconnected man. And the journey ahead of him isn’t about intellect, but about goodness. About connection, humanity, compassion. Becoming not just great, but good. And, if I might add a bit of Johnlock, not just to anyone—but through John, with John, and ultimately because of John.

Now, John’s arc is a little less obvious in my opinion, though just as important—and it’s given to us by Mycroft, who says:

“You’re not haunted by the war, Dr. Watson—you miss it.”

To me, this says: here is a traumatized soldier who never fully came back from war. He’s unmoored, disconnected, half-alive. "Nothing ever happens to me." And the arc we should expect? A man who, over time, things happen to him and he finds peace. Who finds meaning in his civilian life—back in London, in friendship, in purpose, in (perhaps) love. Who, by the end of the series, no longer misses the war.

That’s the setup. That’s what we were promised. Or at the very least, that's what I feel I was promised.

Only… whatever I feel was promised never actually happened.

In fact, Sherlock ends up delivering the complete opposite. In Seasons 3 and 4, the show leans into Sherlock as a mythic, near-supernatural figure—the “adult who never was a child.” This directly contradicts the idea of humanising him. The sudden introduction of Eurus shifts the focus from internal growth to external spectacle. His evolution becomes a reaction to trauma, not a conscious transformation toward goodness.

By the end of The Lying Detective, Sherlock is still fundamentally isolated and emotionally unavailable. Despite supposedly learning to “connect,” he doesn’t share emotionally in any meaningful way—not with John, not with Eurus, not with Molly. The “I love you” scene is a puzzle to be solved, not a moment of genuine vulnerability. John and Sherlock’s confrontation at the end of TLD achieves absolutely nothing in terms of their openness or intimacy.

Sherlock's arc—of becoming a good man—is never achieved. Now, we can argue about that, because Sherlock is a softie at times. He is kind. And don’t get me wrong—when Michael Scott leaves Dunder Mifflin, he’s by no means a perfect boss. But he’s loved by Pam, he’s missed by Jim, and the Dunder Mifflin team has learned to respect him in their own way.

I know some of you are itching to shout that Sherlock's arc won't be complete without S5 and in theory, I agree! But! Lest we forget, Lestrade’s “prophecy” (supposedly) comes full circle in The Final Problem:

"No, he’s better than that. He’s a good one."

This, supposedly, is the great moment of The Payoff. Here stands Sherlock, A Good Man™.

Which… always makes me scratch my head.

Is he, Lestrade? Really? What is it, exactly, in those last few days that convinces you of that? What moment between The Six Thatchers and The Final Problem gives you that impression?

Nothing. Really—nothing. This, for me, is absolutely zero character arc payoff.

Now, what about John—who was supposed to come back from the war, or at most, get his adrenaline kicks chasing criminals with Sherlock through the streets of London?

Mary’s death completely hijacks John's growth as a character. Rather than showing John finding stability in his marriage and family (or with Sherlock, in whatever shape that takes), the show strips it all away. And worse, it distances him from Sherlock once more—throwing him into another spiral of guilt and rage, effectively rebooting his trauma rather than resolving it.

The finale gives John no closure. We don’t know where John is emotionally by the end of The Final Problem. Is he at peace? Are we supposed to believe that a happy montage fixes everything? Does he still crave danger? Does he still feel violent impulses toward Sherlock?

I can’t even begin to think when or how Mycroft’s seed of John’s arc—“you miss the war”—comes full circle in The Final Problem. Unlike Lestrade’s line about Sherlock, there’s nothing that brings that theme to any kind of resolution. It’s as though Moftiss forgot to give John a conclusion altogether.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Sherlock’s words to John in TLD—“We might all just be human”—were meant to gesture at John’s arc. But… why would it?

John never struggled to understand that he was human. That wasn’t his arc. That wasn’t his flaw. He knew he was human and he always craved for that humanity from Sherlock. So what, then, was that line supposed to resolve?

I can play devil's advocate here. Character arcs can be negative. A character doesn't always have to have a happy ending, and had Moftiss boldly done that, I would have appreciated it. But they hadn't- they give us a weird ass montage with John and Sherlock happily giggling at Rosie. It's just feels like there's absolutely no conclusion for John, whether negative or positive.

Adding insult to injury, Mary’s 'speech' during the final montage is actually dismissive of their "growth":

“There are two men sitting arguing in a scruffy flat. Like they’ve always been there, and always will.”

Which completely negates the idea that they’ve changed. At that point, they’re not like they’ve always been. John's quite possibly worse than when we met him.

“The best and wisest men I have ever known.”

Again—what’s with the John erasure? Let’s say, for the sake of argument, Sherlock is better now—what makes him wise? And John’s arc was never about becoming wise, so what does that even mean?

“My Baker Street boys.”

Are they? Are they still the Baker Street boys (I hate that nickname)? We’re never told if John and Rosie move back in. In fact, in a Q&A Moftiss declare John does not return to Baker Street.

And that’s just it, isn’t it?

The Final Problem finale doesn’t fail because it was mysterious or ambiguous or hilariously bad or tragic. It fails because it abandons the emotional contract it made with its viewers in the very first episode. It forgets the arcs it promised, the healing it hinted at, the people these characters were meant to become.

We didn't need a happy ending. But we did need a real one.

#my meta#bbc sherlock#sherlock meta#sherlock holmes#john watson#johnlock#moftiss criticism#sherlock season 4#the final problem#sherlock the lying detective#sherlock analysis

533 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm allowing myself to write one more post on the differences between a Sherlock episode and its script.

But Jesus Fucking Christ Jim!

#sherlock fandom#bbc sherlock#sherlock holmes#chronic illness#chronically ill#housebound#jim moriarty#andrew scott#sherlock analysis#sherlock season 4#sherlockbbc#sherlock s4#scriptlock#james moriarty#literary adaptation

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysing TGG The Pool Scene PART 3:

“Is that a British army browning L9A1 in your pocket, or are you just pleased to see me?”

“Both”

Sherlock is clearly pleased to meet him and Moriarty is glad Sherlock is putting in effort. Let’s not forget the intimacy. If he shoots, they both go down. Sherlock is aware it couldn’t be this easy, nor would he ever want to kill Moriarty anyway. It’s once again the Shakespearian notion that they’re forever connected, intertwined in an intellectual romance, even in death, which makes sense considering their passively suicidal tendencies.

“I’ve given you a glimpse, Sherlock, just a teensy glimpse of what I’ve got going on out there in the big bad world. I’m a specialist, you see”“Like you”

S: “Consulting criminal. brilliant.” A moment of pure admiration from Sherlock.

M: “isn’t it?”

Another parallel. Of course, many of which are the products of Moriarty’s life long obsession with Sherlock.

*John looks at Sherlock* He’s searching to decode whether Sherlock is with him or if he’s aligning with Moriarty on some deeper and more unsettling level. John wants reassurance that Sherlock isn’t crossing into Moriarty’s territory, where morality and loyalty are fluid.

*Moriarty looks at John looking at Sherlock* Moriarty of course notices that, he understands what an influence John is to Sherlock even if it’s subconscious. So he decides to play along, to be the villain everyone wants him to be, thus allowing Sherlock to become the hero, making this moment more comfortable for Sherlock. Ultimately, as I've stated before, Moriarty longs to free Sherlock from the chains of responsibility that don't reflect his true values, thus freeing himself (mostly from the loneliness, by having someone who's on the same page), but to do so he can't risk scaring Sherlock off.

"*Moriarty smiling* No one ever gets to me, *face darkens* and no one ever will”

The singsong tone is followed by a voice drop. It’s not hard to notice that the charisma is an act, it is a part of the Moriarty, "The Criminal Mastermind" persona. So here that first half of the line in singsong is a way to trick John into thinking that this is just a normal “crazy funny villain and the serious hero” situation. Which of course it is not. Then the second part of the line is a very cold “ and no one ever will”. Now that was said directly to Sherlock.

(Let me explain how to understand most of these lines with this example:

Moriarty says something that is such a basic villain line that “villain: 101” should sue. But what he says doesn’t matter in the context of “the game”, if we think of this line literally, the only thing it's adding to the tension of their rivalry is the challenge of unattainability. But it’s not about the game anymore. Nothing in The Pool scene actually is. Such basic villain lines don't matter in their content. All that matters is HOW Moriarty says them. The words were basically said to John, but the intention behind them was bluetoothed directly to Sherlock.)

He says it so calmly and yet with a note of despair, this hopeless level of indifference and emotional resignation that he couldn’t hide, that his fun act can’t cover.

This line has more significance than it seems so on the surface. A theory is that with this line Moriarty admits to his loneliness, he jokes about it first, concealing the meaning behind with the very literal unapproachability that comes with his job, but ultimately no one gets (to) him, because no one understand/reaches him personally and emotionally. He might even be sceptical that Sherlock actually could, maybe he’s Moriarty’s only chance, which considering what happens in the Reichenbach fall, seems to become a reason for his suicide (with calling Sherlock "ordinary"). He’s been disappointed all his life, he’s so used to the isolation, so it seems natural to doubt the possibility of happiness. And so he communicates that with Sherlock, his only chance, he reaches out, because he knows Sherlock understands that feeling, that untreatable loneliness of unreachable ideals, which in a way makes it all even more heartbreaking. This glimpse of hope, Sherlock, in front of him and a painful crumb of realisation (“and no one ever will”) that the connection he seeks may be impossible after all…

*cocks gun* “I did” Sherlock doesn’t let the moment linger for too long and answers back with confidence.

Sherlock truly is the first person to really meet him. Moriarty is a puppet master which means everything is done remotely, he “knows people”. But Sherlock is the only person who was actually allowed to see him, whether literally or figuratively.

Now… I would normally leave it at that, but something about this moment hooked me. I must warn you that this is some deep water, bottom-of-iceberg shit that you’re about to read.

REGARDING THE *cocks gun*:

I did some mild research and cocking a gun usually means “establishing control, authority”, I think everyone knew that. But what’s interesting is that the gun useless here in a traditional sense. It isn’t a threat, as NO ONE HERE CARES ABOUT THEIR LIVES. Which then means that it’s symbolic.

I WON’T BE ANALYSING THE GUN SYMBOLISM HERE. PLEASE I’VE BEEN IN THE DUNGEON WRITING 20 PAGES OF THIS ALREADY (I want to do it someday though, I think it's very interesting and GAY)

What will do though is walk you through everything that this moment could mean. Which is a lot.

1. Playing the Hero for John

The *cocks gun* moment is, above all, for John. Sherlock knows that John needs reassurance, not just of his safety but of Sherlock’s allegiance to morality and goodness. The cocked gun signals that Sherlock isn’t on Moriarty’s side, that Sherlock hasn’t been seduced by the villainous allure of Moriarty’s chaotic world. It’s a signal to John that, at least in this moment, Sherlock chooses him.

2. Sherlock’s fear of vulnerability and threatened identity

It’s also important what that gesture means to Sherlock himself. He’s in the middle of this intense intellectual and emotional push-and-pull with Moriarty, someone who fascinates him, understands him, and yet challenges him in ways John can’t.

Sherlock is so invested in maintaining the illusion of invulnerability, not just for Moriarty or John but for himself. Acknowledging fully that he loves and needs this connection would shatter the way he defines himself.

Sherlock’s fear of vulnerability runs deep, and it often manifests as denial—of feelings, of needs, even of his own humanity. With Moriarty, the connection is so raw, so intense, that it’s almost impossible for Sherlock to face without losing the carefully constructed emotional distance he clings to.

Cocking the gun could be a way for Sherlock to reassert his own identity, to remind himself and everyone else that he isn’t like Moriarty, that he has lines he won’t cross. The gun becomes a tool of self-protection, not physically, but emotionally. He’s essentially saying, “I’m not like you. I’m not drawn to you. I don’t feel this.” But the very intensity of his reaction suggests the opposite. He does feel it, profoundly, and that terrifies him more than any bomb or bullet ever could.

3. Emotional Deflection through aggression

Sherlock is creating a barrier between them by cocking the gun, a way to avoid confronting the depth of their connection.

And then there’s Moriarty, who seems to recognize this instinctive defense for what it is. He doesn’t flinch, he just watches with this almost knowing, dark amusement, suggesting that he sees right through it. Moriarty understands that Sherlock’s aggression is rooted in fear, and maybe even hurt, at the prospect of what their connection means. Moriarty doesn’t flinch because he knows the gun isn’t the real weapon here, it’s Sherlock’s emotional avoidance. Moriarty’s indifference to his life in that moment reinforces this. He’s not afraid of dying, what wounds him is Sherlock’s inability (or refusal) to meet him on that emotional plane, even though it’s what they both crave deep down. And to be fair threatening with a gun is such a "normie" move. Not only isn't it a threat, but Moriarty probably likes it. Ignoring the emotional connotations of this moment, this was flirting more than it was ever tactical.

In a way, both of them are locked in this tragic dance, afraid to admit they want the same thing: to be understood, to be gotten. But while Moriarty expresses his fear as defiance, Sherlock buries his in shame and instinctual rejection.

It’s also ironic that he hates the idea of being a hero, of being boxed into John’s moral framework, but he uses it here because it’s convenient. It gives him an excuse to push Moriarty away under the guise of righteousness.

4. Returning to the Game to Avoid the Emotion:

Sherlock’s inner conflict: He needs to say something to continue the game (which they both love), but the truth behind his words is dangerously real: “I see you. I understand you.” It’s a confession disguised as a taunt.

The *cocks gun* and “I did” together are Sherlock’s attempt to drag the moment back into the comfort of their shared game, away from the messy, vulnerable reality beneath. Let's not forget the line before this "No one ever gets to me, and no one ever will". Sherlock's smug answer is almost like saying "yo, what are you talking about, can we just like, be normal?".

The line is textbook intellectual sparring, a move in their game, where Sherlock is claiming a small win over Moriarty. But beneath the surface, this line is charged with raw emotion. It’s Sherlock’s way of acknowledging Moriarty’s vulnerability while hiding his own. The cocky delivery is Sherlock’s shield, a way to keep things “in the game” rather than letting them spiral into the emotional realm that terrifies him.

This is classic Sherlock. He frames everything as intellectual so he doesn’t have to confront the emotional. But the irony, is that his response betrays his emotions more than he realizes. By adopting the “hero” role here, Sherlock not only reassures John but also deflects attention from the growing tension between himself and Moriarty.

Yet Moriarty hears the disguised confession in “I did,” even if Sherlock is trying to drown it out with smugness. It’s like he’s patiently waiting for Sherlock to catch up emotionally, to stop hiding behind his role as the hero and see the truth of their dynamic for what it is.

SUMMARY:

On the surface, it’s a simple game move: Sherlock reasserts control. But beneath that, it’s profoundly emotional—two people who understand each other deeply, who see themselves reflected in the other, but who are too guarded to fully acknowledge it. It’s a moment of connection, disguised as competition, wrapped in deflection.

M: “You’ve come the closest. Now you’re in my way”

Basically to translate: “you are truly remarkable, because you’ve gotten so close that now you’re capable of disrupting my plans, which no one before was able to do”.

The singing tone this time implies that his plans, his work don’t mean much to him. Sherlock is in his way and he doesn't mind one bit. It’s not really about all that, all his criminal work was the best high he could get when he couldn't have a connection with Sherlock. The real point here is that Sherlock cracked him, Sherlock passed the test. He saw through his villain behavior and found a lonely, tortured sould just like him. Sherlock was able to understand Jim and that intimacy is what Moriarty values more than anything. So yes, it is a compliment. but Moriarty says “closest” as if it’s still not close enough, that’s a hint for the hopelessness Moriarty feels. I don’t think at this point they’re fully aware of just how deeply they need one another, the feeling of being understood, valued and accepted, whilst being intellectually stimulated and entertained. “Thank you” Sherlock demonstrates their understanding and connection, even if here he's probably answering in the context of the game(aka: he's the first to come so close to an opponent of such class). And he genuinely appreciates the compliment, their mutual respect is apparent.

M: “I didn’t mean it as a compliment” was definitely teasing.

S: “yes you did”

M: “yeah, okay I did” (cutie :3)

^(MY FAV MOMENT EVER)

#jim moriarty#sheriarty#bbc sherlock#james moriarty#sherlock holmes#sherlock bbc#sherlock fandom#sherlock analysis

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys lately I’m in a big Moriarty and BSD brainrot and my big brain has been WORKING over both of them.

I often see people comparing William and Fyodor and I mean sure, I don’t know Fyodor enough to tell you how much they might be similar, but then who is Sherly compared to ? I always see dazai, but I think that y’all are just missing out on this one.

Sherlock is Ranpo. And I know I just lit up something in your brain right now if you never thought about it.

I’ll go over some points that I can think of right now to prove my point.

Both are from highly intelligent families, Sherlock had at least his brother, so Mycroft, that is astonishingly smart too, and Rampo had his parents that were absolute geniuses (information given by Fukuzawa in Untold Origins)

SO they both grew up in a very special environment where their brain developed amazingly so now they can use to it’s max capacity. They were constantly stimulated by someone even smarter than them throughout their whole life, making them the big brains they are today.

BUT ! This created an uneasiness towards society, people are dumb in their eyes and they take interest only in what is special and exceptional, and like they like to call it, in things that « deserve their attention » as intellectually superior people.

They don’t fit in because their intelligence make them eccentrics, they behave differently because they see things differently, only a few people are able to more or less manage them, and it either takes someone dumber or at least as smart as them (for Sherlock you can think of William or Mycroft vs Watson and Lestrade as for Ranpo I would say Dazai or Fyodor vs anyone in the agency tbh)

Also both of them have a way to put their mind at ease, Ranpo being sweet things and food in general and Sherlock being cigarette and sometimes violin. It probably helps they either distract themselves or on the other hand to concentrate.

Also they’re both very much autistic <3

Anyway that’s it for now thanks y’all for reading have a nice one and read Moriarty and BSD !!!

#moriarty the patriot#yuukoku no moriarty#sherlock holmes#sherlock analysis#bungo stray dogs manga#bungou gay dogs#bungou sd#bsd analysis#bsd manga#bsd#bungou stray dogs ranpo#ranpo edogawa#bsd ranpo#ranpo analysis

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think a lot of modern Sherlock Holmes adaptations (as in, Holmes in the modern era) miss out by having Holmes work so closely with the police. A lot of people forget that Holmes was one of the original ACAB bitchies in fiction; he did not like the police. Yes, he worked alongside them sometimes, but he often talked about them with open distain. Sometimes he even worked directly against them (think of The Norwood Builder).

Granted this was mostly because the police lacked a lot of the skills they have today, such as forensics, something that Holmes was an advocate for, and tended to draw conclusions that did not fit the obvious facts. This has obviously changed - the police have a lot more resources at their disposal nowadays, but they are not a perfect institution - far, far from it, and if he were alive today, Holmes would have a lot to say about that.

I wish modern adaptations stayed true to the fact that in canon, Sherlock Holmes was the man you went to if you could not go to the police. If you had, perhaps, a criminal record, were homeless, were POC, were queer, were neurodivergent, an abuse victim, reliant on illegal substances, or even wrongfully accused, Sherlock Holmes would be the man you went to, and he would help you to the best of his ability.

Also, Holmes had his own unique sense of justice. Think of The Abbey Grange - a man murders the abusive husband of an old lover, and the wife is complicit. Holmes and Watson ultimately decide to let them go - Lady Brackenstall was being horribly abused, she was trapped in a loveless marriage with a violent husband. Captain Crocker murdered Sir Eustace, freeing Lady Brackenstall and perhaps saving her life. If the police had arrested Crocker, it would be very likely he would be hanged for murder, regardless of the circumstances.

Then there is James Ryder in the Blue Carbuncle. He, after Holmes pesters him, freely admits to stealing the jewel, but Holmes does not hand him over to the police and instead lets him walk free. It was Ryder's first offence, one he was manipulated into committing, and Holmes and Watson see him as a, quite frankly, pathetic little man. Holmes realises that if he were to turn Ryder in, it would destroy his life - he would be 'a jailbird for life'. Ryder committed a crime, but he is no criminal. Prison would turn him into one.

Holmes takes justice into his own hands, and in a way, it turns him into an anti-hero. But I think this a part of what makes him such a loveable, iconic character.

Holmes has created a 'safe space' within 221B Baker Street. I think this would be extremely intresting to explore through a modern lens.

#mine#i woke up this morning with Strong Feelings and i wanted to write them down#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#acd canon#sherlock holmes analysis#sherlock holmes meta#i admit i havent seen every modern adaptation so if this already exists........sorry#acd sherlock holmes

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw an essay here a while ago that talks about how the first time Holmes and Watson move in together, it’s out of necessity, and while Watson admires Holmes a great deal, he’s still shocked by Holmes’s methods and impropriety. When he first proposes to Mary, he tells Holmes that he will no longer be going on adventure with him. I view that as an attempt to try to build himself a “normal” life. To try and blend in with society, to have a semblance of the stability he had before he went to war.

The thing is, he keeps coming back to Holmes. At first, in A Scandal in Bohemia, they haven’t seen each other in a month or so. But they instantly click back together. Watson stays at Baker Street once again, and takes part in the harrowing, law bending adventures once again. And again. And again. Visiting Holmes more and more frequently, living in excitement and close companionship with him once again. There’s still the normal side of his life, but it’s in the background.

After Holmes’s “death”, Watson might have realized that he doesn’t WANT “normal”. He wants the life he had with Holmes, but it’s too late.

Then he returns. Watson sells his practice and moves back in with him, and the adventures continue until they grow old.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#acd sherlock holmes#acd canon#acd sherlock#john watson#dr watson#acd dr watson#acd watson#sherlock holmes analysis#mary morstan#< she really got the short end of the stick

439 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do think there are a lot of valid criticisms regarding modern media consumers' impatience. There definitely is an unwillingness to let plots develop or initially flawed characters grow and change, and that's definitely a problem. Gratification can't always be instant.

But we also have to consider that there's a whole lot of shows that have promised us so much and then absolutely failed to deliver on it. Sherlock, the Moffat and Chibnall eras of Doctor Who, Supernatural, Game of Thrones, The Expanse to a lesser degree - they all had a lot of trust invested in them by audiences only to betray it.

I don't support the level of impatience modern audiences show towards media but I absolutely understand it.

#narrative#storytelling#sherlock#doctor who#supernatural#game of thrones#the expanse#to a lesser degree#media analysis#media consumption

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final Script- BBC Sherlock S4-

The Lying Detective

For a bit of recap and a few things we might have missed I recommend this vid:

youtube

And onto the script!

As I suspected, there were FAR fewer differences between the script on the BBC website and the broadcast episode than with The Six Thatchers, which had many! I do think there may have been a later 'Amends' script for TST and the Beeb uploaded the wrong one, but hey, I'll never know.

Anyway, what follows are a few minor changes I did spot, interspersed with my favorite bits of stage direction.

Fake Faith's Hair

The 'Faith Smith' that comes to Baker Street is described as having both jet black hair and her roots grown out- it seems at some point they were considering Eurus appearing with her 'natural' hair colour here but looking as 'Faith' as if she's dyed it. I mean Eurus' looks completely too, but I've headcanoned about that elsewhere! So perhaps that was a discrepancy left from an earlier vision. That or someone had to fill in Steven Moffat on the workings of dye.

It's Mrs Hudson's Episode!

There are too many amazing lines of hers to quote here, but I also enjoy these notes.

"Sherlock Vision"

Mildly amusing.

Childhood Flashback

As with TST, they were intending to go further with this sooner. Notice also that Sherlock 'freaking out' has been condensed from two incidents to one.

Another interesting line here that I think got cut:

And...

I think my tiny attention span and poorly ME/CFS addled brain failed up pick up on the cut to the aquarium until now.

"We just carpet the wall.."

I enjoy the 'it'll be easy I promise!' vibes of the description of Sherlock blurring locations and dimensions on his return to the flat. Tumblr won't let me upload more images though.

"Once More..."

Something that surprised me about the script is that it has much of Sherlock's Henry V 'Once more unto the breach dear friends' speech delivered off-camera, showing Mrs Hudson nervously moving to investigate in the hallway and Wiggins dashing out, building for longer to the reveal of Sherlock reciting and gesticulating wildly with a gun.

One can only imagine that the decision was (correctly) made not to waste even a few seconds of Benedict Cumberbatch having the time of his theatre nerd life!

Missing Scene

We eventually get to the deleted part that sent me down my script-study rabbithole: John's failed attempt at drink driving. I too was horrified when I first read these lines, having always had the abject disgust at the very notion of drink-driving that many millenials do and that older generations often lack.

Not that I approve of John's extramarital text flirtation, of spectacularly dumping his best friend and violent attack of the same!

John really is out of control and as always, he appears somewhat normal next to Sherlock. John's quiet breakdown involves whiskey at home, chronic insomnia and just about managing to hide his hallucinations from his therapist; Sherlock's much louder one involves wild eyes, track marks, an elderly landlady in a sports car, a helicopter chase and an ambulance. But as always, while Sherlock is by far the most unpredictable and flamboyant, John is just as dangerous if not more so.

I feel that this scene was cut because it really wasn't needed, and it doesn't make massive sense for Sherlock to have been sneaking around successfully watching over John when he was meant to be "off his tits" anyway.

Smith's Mobile Phone

There's then a minor point in the script about Sherlock having deduced Smith's phone password/code and another reference to something being hidden "in plain sight". It seems that it was actually the "Serial number" on the back of the phone. I don't think we lose anything from this seeing as 'plain sight' comes up a lot and it's been long established that Sherlock can crack most passwords with ease.

Smith as a Mirror for John

I have seen Smith described as a John mirror before, particularly in the shot where they stand opposite each other across the slab. And while that shot IS compelling and lord knows their hair styles are the same, I did wonder if it was just a case of them both having the same stylist- Mary's do has the same kind of vibe about it after all. However, on this rewatch I finally got it: neither is the man with morals beyond reproach that he is often seen as, both carry darkness and at least one secret, and both have killed without remorse. The irony of Smith- clearly delighted- saying "no violence please" as John takes out all his fury on the frail, felled Sherlock is appropriately sickening.

The Stolen Scalpel

The script in the mortuary scene describes close ups on the tray of tools when Culverton Smith would've had a chance to swipe a scalpel, and him standing with his hands behind his back as if he has, giving the impression that Sherlock was reasonable to think he had done that- when in reality of course it was Sherlock who had grabbed it. In the episode Smith does stand right by the tools and technicaly could've pocketed one or something but shows his hands very demonstrably after that, making Sherlock's accusation seem to appear from nowhere. I'm not sure if this will have been cut down because of the blocking and camera stuff not quite having worked, but making Sherlock look even more unhinged doesn't hurt. If he can hallucinate Smith taking the scalpel, Smith laughing non-stop, then has he hallucinated Faith?

'The Scene'- Yes That One :-(

I was intrigued to see the stage directions for 'the scene' i.e. John's rather extreme violence against Sherlock, and indeed the script describes him as having completely lost control in a fury that's upsetting and disturbing to see.

Without any intention of trying to justify John's behaviour (though he clearly was Not Fucking Okay), I have mentally disputed the idea that John "put him in the hospital" before. Sadly I did once see a loved one take a beating at least as bad as that and the police barely even check them over, let alone have them taken to the hospital. But enough of my trauma...

In the script Nurse Cornish says that Sherlock will "probably need" the walking stick, and that has been cut from the final product- as have a lot of unimportant lines, to be fair. Though we can assume John, being a doctor, reasonably thought he might benefit from it, perhaps having cracked a rib or too.

It was only on my latest rewatch that I realised "Mary" isn't in this scene at all. And last time we saw her, she was asking if John still missed her- presumably now that's back out on a case with Sherlock. In fact since Sherlock arrived to get John, Mary's ghostly prescence has been less and less. Here in the mortuary, John's mind is completely occupied with the drama of it all, never projecting her.

I'm not sure what I think of this, especially because there can only be so many things shown at once, but back in The Empty Hearse it was Mary constantly trying to calm John and push him.to reunite with his old friend. Here hallucinated Mary encourages John to tell the truth to his therapist and sticks up for Sherlock at every turn. Is this the nadir of what John and Sherlock could become "without (her)", as Mary intimates in the "I miss you" video next episode? Sadly it seems so.

"Isn't That Right, Mary?"

On to a much more pleasant scene: drinking tea in Baker street. The script mentions here that it be blocked and shot as if John is talking to theoretical Mary instead of a hallucinated/visualised Mary that's actually there. Sherlock doesn't say "isn't that right Mary?" after "I'm Sherlock Holmes, I wear the damn hat." A nice addition I think. I'm not dure it would really have worked without John speaking to a specific Mary there and then without Sherlock deducing otherwise.

"Unless she calls."

Finally, in the following scene between Mycroft and Lady Smallwood, the gender of the PM has been changed. The script calls "him" an "idiot", where the finished episode merely implies that "she" is a nuisance of some kind. Another minor change is that Mycroft is more indecisive about taking Lady Smallwood's card-in the script he is seen nearly taking the card at least twice. Her seeming to be hitting on him threw me a little the first time as I read Mycroft as openly gay, but hey, that's just me. I hope they became besties at the very least!

If you made it this far, thankyou for tolerating my ramblings and proving to myself again that yes, the changes made from the shooting script were improvements. You're welcome Moftiss.

#sherlock fandom#sherlock holmes#bbc sherlock#chronically ill#chronic illness#housebound#bed bound#me cfs#chronic pain#chronic fatigue#chronic fatigue syndrome#hyperfixation#i'm hyperfixating again#scriptlock#sherlock meta#sherlock analysis#dr john watson#john watson#mary watson#sherlock bbc#literary adaptation#literary fiction#literary criticism#sherlockbbc#martin freeman#steven moffat#mark gatiss#british tv#british actors#literary analysis

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Dr Watson fooled a nation: And why we continue to hide his secret

Everyone has heard of Mr Sherlock Holmes: within the same breath, we are usually moved to mention his companion, and the man who we have to thank for narrating the famous detective's life, Dr John Watson. One only has to mention a terrifying hound, perhaps relate to a watery death by the Reichenbach falls, or even (for more dedicated readers) discuss retirement in Sussex, for the name ‘Holmes’ to come to mind. Who out of us has not responded to a blasé statement with the phrase ‘No shit, Sherlock’? Who out of us does not link the deerstalker and pipe to the familiar detective? Who out of us hasn’t watched a single adaptation, in which the malicious Moriarty or mysterious Mycroft are referenced? It is highly improbable one has never heard of this detective duo, even if one hasn’t ever been moved to read any of the sixty stories produced over a forty year time frame. Sherlock Holmes and John Watson are icons, arguably cemented into the fabric of the nation.

But how much of it is true?

Obviously, it is fair to state that no, none of the fictionalised work penned by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is real, aside from occasional real-life inspiration (such as Sherlock Holmes being influenced by Sir Doyle’s deductive teacher, Dr Joseph Bell, or John Watson feasibly being a stand-in for the author himself). Although, it is worth mentioning that in a 2008 study, 58% of British teenagers believed Mr Holmes to be a real detective (whereas 23% thought Winston Churchill was a fictional character), so it is worthwhile to first and foremost clear up this grey area.

However, for many Sherlock Holmes fans (often called ‘Holmesians’ or ‘Sherlockians’) we take our reading a few steps further. Perhaps Dr Watson was fictional, but are his narratives also fictional within his reality? We, as readers, are only able to read what he writes (apart from the select few cases in which Holmes has his say, or the elusive tales where the narrator is unknown… more on this later), so how do we know if he is telling the truth?

Personally, I have a hard time believing anything Watson tells us, as he is proven to alter the truth to fit his own preferences on multiple surface level cases. Famously, he creates quite a bit of uncertainty surrounding his wife, introducing her as Mary Morstan, the orphan in need of rescuing, then including her visit to her mother’s in The Five Orange Pips- and this is only the beginning of his falsehoods. Watson shapes the narrative to suit his needs, contradicting himself through many ‘mistakes’, which could be attributed to his (or, more believably, Sir Doyle’s) forgetfulness. After all, many people have minced up the dates of events in their life, or forgotten the name of their landlady, or been called the wrong name by their wife…supposedly. Can we not forgive Watson/Doyle for mild absent-mindedness?

Admittedly, this is the easiest and more likely option. Over the forty years, Sir Doyle’s attentiveness for chronology understandably dwindled, given that his dedication to the detective eventually waned. Sir Doyle wanted to explore different aspects of life and his career outside of serial ‘penny-dreadfuls’ which required new and updated twists and turns every week, and can we blame him? But, I ask you, dear reader, to suspend your disbelief momentarily (committing to death of the author), and imagine a reality in which Sherlock Holmes and John Watson actually lived and worked in 221B Baker Street, solving crimes and going on adventures in and around London, whilst the detective’s ‘Boswell’ dutifully wrote-up and published their time together on The Strand.

Now, I reiterate my initial question, how much of it is true?

In whichever adaptation you have watched (as I highly doubt you have never glimpsed any), whether it be an exciting action movie version; a modern-day update which rose to fame as quickly as it… disappointed; a more faithful television series that pulls direct dialogue from the canon; a movie series clearly laced with war propaganda but still beloved; or any adaptation produced over the past century, one element is essential to any retelling of these well-known stories- the topic of Holmes’ and Watson’s relationship. To joke about two close men living in close quarters with each other potentially being gay is a tale as old as time (although this joke can have serious real-life implications) but to believe it? To say that, yes, Holmes and Watson were in a loving, homosexual relationship with each other and were incredibly happy together- this is not taken seriously. It is attributed to the recent surge of ‘over-homoerotisicing’ male friendships and not allowing men to just be friends; or, dismissed as usual ‘fangirl shipping’ without any real understanding as to why many believe this to be a fact. (I should point out, the phrases I have written between apostrophes should be read with both sarcasm and tiredness, as I do not believe it is fair to state either of those occurrences as lesser than, or something to mock).

When I first approached the canon at the ripe age of eleven years-old, I came from a background of murder mysteries suitable (sometimes unsuitable) for young eyes, all under the shadow of Sherlock Holmes, and was beginning to watch a certain infamous television series which probed at ‘gay’ jokes like a bear sticking its paw inside of a bee’s nest and surprised when it is stung. Of course, I was learning about this new and interesting ‘fandom’, where people viewed pages and scenes under a microscopic lens, searching for intertextual clues or meta thematic elements that might just hint that the two main male leads, known for their intimate association, might, maybe, potentially be more than friends. I took it all with a grain of salt. I knew what ‘gay’ meant, and knew I was likely gay myself (I told myself that was a ‘problem’ for later), but I had hardly ever seen it respectfully depicted in the media. Sure, the odd mention of a gay man was possible, but for it to be treated the same way as a heterosexual couple might? Doubtful- I wasn’t holding my breath.

I read the Holmes books with a sense of glee, like I was being accepted into some sort of ‘community’- one of iconic detectives and the ability to off-handedly reference exactly how Holmes deduced Watson’s brother was a drunk (scratches around his pocket-watch keyhole, a mistake a sober man would never make) and to say ‘elementary, my dear Watson’ whilst wearing a deerstalker and smoking a pipe… all in my young imagination, of course.

I was obsessed. From the start- Watson’s direness to find a suitable flatmate, indicating a life of misfortune, followed by a miserable descent into adulthood, only to find Holmes, a light in his darkness. Their adventures full of action and twists and turns and fear, at times, all parenthesised by breakfast at Baker Street and supper at Claridge’s, or a visit to the music hall. All of it felt comfortable, familiar- baring Watson’s unreliability to tell the whole truth, which, at the time, could be ignored.

As I’ve grown up, I’ve revisited these stories multiple times, ‘silly’ detective stories which might not have the same depth and subtext as Dostoyevsky or Dickens.

Slowly, I lost faith in that belief.

Led on by like-minded people who also agreed that Holmes and Watson (in whichever universe they existed) were more than friends, I began to invest in the evidence, which I hadn’t realised had been glaringly staring me in the face all along. Whereas before, I told myself that Holmes and Watson were never intended to be together, it was impossible and merely a light-hearted misreading of the text, I started to join the dots. How I solidified my belief?

1895.

‘Here dwell together still two men of note’, so begins Vincent Starrett’s poem, titled ‘221B’, where he claims ‘it is always eighteen ninety-five’, often cited as Holmes’ most successful and ambitious year of solving crime. Watson tells us specifically which cases happened in this notable year, without any need to search for intertextual clues that the cases of The Solitary Cyclist, Black Peter, The Bruce-Partington Plans and The Three Students all occurred in 1895. Surprisingly, we are given specifics: respectively, we are told these cases happened on the 23rd of April, July and November, although he wasn’t as precise with The Three Students. In fact, in this case, Holmes and Watson have left London, for reasons he doesn’t care to indulge.

What else occured in 1895 which has so convinced me Watson was cleverly concealing the true nature of his and Holmes’ relationship? The shocking Wilde trials.

The celebrated author and playwright who bolstered the aestheticism movement, or ‘art for art’s sake’, was found guilty of gross indecency and imprisoned for two years- this led to many homosexual couples evacuating London, for no given reason. Why on Earth would Watson specify a year (which, as many readers know, dates are not spared lightly in a Watsonian narrative) only to refuse to provide information as to why he and his close, intimate associate decided to leave London? Why specifically 1895, a year apparently not short of mystery and intrigue for the detective duo? Why else but to hint to knowing readers of the Victorian/Edwardian period that there was something more to the stories he told? And this, dear reader, is why I (finally) state my case: Holmes and Watson were a homosexual couple in a time when their mere existence was vilified and criminalised, so to protect themselves, Watson began to publicize their life under carefully constructed narratives- one big lie wrapped in truths so it is deemed believable. The cases might be real at times, as Sherlock Holmes was still a detective and Watson a doctor, but could be reflective of other events in their life, or Watson’s own imaginings to fill up a gap where they were, for example, out of London for reasons Watson ‘need not enter’. Those inconsistencies and mistakes? The elusive wife who might be an orphan or might be at her mother’s or who might have passed? The shifting chronology which is near impossible to pin down if we believe everything Watson tells us? Breadcrumbs.

Watson is lying to us, and he hopes that one day ‘the true story may be told’.

Therefore, I have attempted to construct my own order of the published cases, both when the events occurred and when Watson wrote them up (somewhat like William Baring-Gould, but with a very different mindset) to establish where he has told us the truth, or where he truly takes on the title of ‘unreliable narrator’ to hide his and Holmes’ romantic relationship. In doing so, I’ve wilfully ignored much we have been told directly, often creating my own lines to read between, but trying to gauge the mindset of the biographer turned doctor to understand the reality of this piece of fiction and faithfully reproduce an order of events. I will add, Watson is a complicated man, too humble to admit that in his own narrative of course, and should these stories all been written by Holmes (unlikely), I might have found it easier since I understand his mindset better. Whilst connecting these cases, I felt like Holmes on a case, but grasping the human nature, the human errors behind them? I needed a Watson.

Reader, I admit, I have taken liberties. But all, I believe, are justified. Again, I ask you to suspend your disbelief as we return to the very beginning: the Criterion Bar, 1881.

#sherlock holmes#sherlock#acd#acd canon#sherlock holmes meta#dr watson#watson#john watson#literary analysis#the-secretary-of-baker-street

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

OMG such analysis!!! Bravo!!!

The 5 things we learned from John and Irene’s meeting

1) Sherlock indeed follows John everywhere.

2) Irene Adler is truly in love with Sherlock. As she confesses, she made a mistake. When she was hiding from her enemies, when she thought she would probably die, when she faked her death to escape, she sent her camera phone to Sherlock. This was a silly and impulsive act. She did it for two reasons: a) she thought Sherlock would never imagine this password and b) she chose to give it to the person she loved the most. You don’t trust your most valuable object to an enemy. But when she returned, now wanting it back, she realized what she did was stupid, because a) she put Sherlock in danger and b) now Sherlock would start suspecting that she honestly loves him (but Sherlock already suspected it anyway). So she asks John’s help in order to retrieve the phone under Sherlock’s nose, because she didn’t want to reappear in front of him. In this case she’d have to find a bloody persuasive excuse to explain why she gave the phone to him in the first place.

3) John loves Sherlock more than Irene and the fans can even imagine. Irene thought John would agree to help her in order to let Sherlock believe she ‘s dead, because he doesn’t want her competiveness.

JOHN: Tell him you’re alive. IRENE: He’d come after me. J: I’ll come after you if you don’t. I: (sarcastically) Mmm, I believe you. (”As if you didn’t wish me dead, so you could have Sherlock all for yourself.”) J: (chooses not to reply to her last comment): You were dead on a slab. It was definitely you.

However, she is completely wrong. John cares about Sherlock’s emotional stability more than his own repressed feelings. He forces her to tell Sherlock she’s alive hoping that this will make him stop being miserable. Irene looks genuinely impressed by his love.

4) John Watson’s sexuality. Ok, this may be a long shot, because it is easier to understand Quantum mechanics than John Watson’s sexuality. It is very easy to just say that John is obviously a raging bisexual, as I see he’s characterized lately, but to my eyes the truth is more complicated, especially if we take into account the differences in the way John confronts this issue in every series. The S1 John is not the same with the S3 John. S2 John is somewhere in between. So, apparently, there is progress. More quantum mechanics under the cut:

Keep reading

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Phone her, text her, do something, while there’s still a chance. Because the chance doesn’t last forever. Trust me, Sherlock, it goes before you know it. BEFORE. YOU. KNOW. IT"

And then Sherlock looks like that

Looking at John helplessly, eyes intermittently twitching towards him.

Look, I know John is talking about Mary here, and I also know our dear detective's aware of that.

HOWEVER !

The way Sherlock just. Looks devastated. means he understood perfectly what John said.

More than that, he feels it.

But at the end of the conversation, Sherlock doesn't go "ah, yes,you're right, let me phone her, let me go to Irene Adler."

No, he goes to comfort John. To stay with him. He embraces him.

And when John admits the "cheating" part, Sherlock immediately connects this to "even I text her sometimes. The Woman"

Sherlock associates texting Irene Adler with cheating on someone. I'm pretty sure that's why he never does it.

On who, I wonder ?

#the answer is John Watson#in case that wasn't clear#JUST LOOK AT HIM ! JUST LOOK AT HIS EYES ! THE WAY HE IS GAZING AT JOHN !#He knows that chance doesn't last forever#He was gone for two years#look what happened#Sorry#The Lying Detective#bbc sherlock#johnlock#meta I guess ? No not really#More like#analysis nobody asked for

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock Holmes, despite being one of the most adapted characters in media, is almost always characterized differently than in the source material. Despite having a habit of unnerving people with his deductions, and his distaste for the police force, Sherlock Holmes is canonically good at reassuring people, gets along amicably with clients, and has an affectionate relationship with Watson. However, he is almost always adapted to be extremely stoic and unable to interact with people in a regular fashion, as is a common trope with genius characters. Whether being smart but socially inept is a caricature of Savant Syndrome or a result of an effort to create flaw in a character whose skills were not balanced out with much deficit, it is clear that Sherlock Holmes has been the subject of much transformation in the public consciousness, straying from the envisioning of Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle. Is this modified personality better, creating a more well-rounded and interesting character? Or, does it instead stereotype and boil down the traits that, left alone, made Sherlock Holmes the quintessential star of detective fiction, restorting to trite and digestible cliché? In this essay I will

#sherlock holmes#sir arthur conan doyle#john watson#we live in a society#is this a joke?#i dont know anymore#sherlock#lil analysis for yall

809 notes

·

View notes

Text

hellooooooooooo divas. i have a rant about lou because nobody is talking about him. :(

so, he's very dramatic and his main goal is keeping up appearances for the crowd. that's his whole thing. he says multiple times that being pretty is everything, meaning to him, his appearance, both physically and publicly, is the most important.

but by the end of the movie, he's been stripped of both.

you can see the difference here between when he's putting up an act (left) and when he's actually showing strong emotion (right). for a movie that's admittedly not the best quality, he's a very well written villian.

you can tell that his friendship with ox wasn't fake, despite his betrayal.

he used to be kind and caring, though still with flaws. the only reason he turned on ox is because he knew that even though they were close, ox would get to leave and lou wouldn't. i think it was a mix of feelings.

jealousy, because lou couldn't go to the big world and ox could. betrayal, because ox would be leaving him. loneliness, which is pretty obvious.

i mean, being lonely is a classic villian backstory. but his is good because it's not just like: "well he wasn't good at making friends :(" it's literally "he couldn't keep friends".

i think a huge reason that lou values his public appearance is because it's all he's got left. it's the only time that people valued him. eventually popularity got to his head, so he's vain.

i've seen some people argue that the reason he makes his lessons so hard is because he'll miss the dolls. but honestly, i think he's just jealous that they get to go to the big world. which though cruel, is kind of justified.

i mean, look at this shot. it's probably my favorite in the whole movie. he's living his worst fear in this moment. he's lost his popularity, he's lost the game. and the uglydolls passed. everything he's been shown to care about has been taken, and this shot encapsulates it PERFECTLY.

(and it makes me very sad. i could watch the titanic with a straight face but unfortunately i'd watch this and then bawl for like thirty minutes. i don't wanna talk about it.)

anyway, i'll stop ranting. gooodnighht everyone.

#sherlock gnomes#lou uglydolls#ugly dolls#uglydolls#uglydolls lou#character analysis#i love him#please read this#rant post#mini rant#aaagghhh#uglydolls moxy#uglydolls uglydog#uglydolls blabbo#uglydolls tuesday#sorry for the rant

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

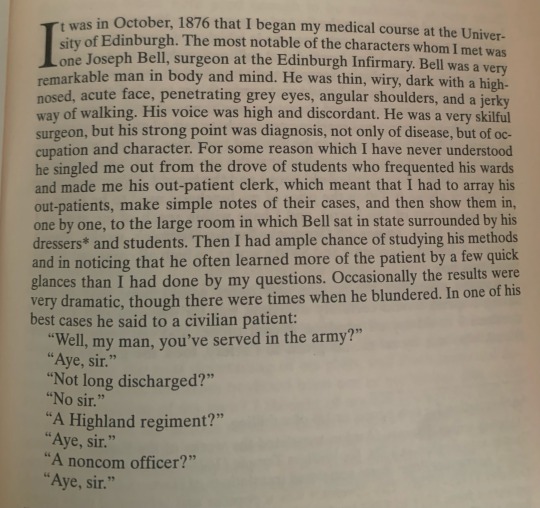

I love learning about the inspiration for Holmes. It’s also worth noting that Doyle talks about Bell in a very similar manner that Watson describes Holmes (high nosed, acute face, penetrating grey eyes etc.) and has a similar admiration for the doctor’s skills and intellect as his narrator has for his literary counterpart. Holmes is also occasionally described as explaining his methods to watson like a teacher addressing his class, which is most likely referencing his real life model being a professor.

I love that Bell kept an interest in Doyle and his stories, and I’m wondering if his “impractical suggestions” were what was being mirrored in Holmes’s critique of Watson’s romanticism:

‘Doyle, this is entirely unrealistic!’

‘I’M TRYING TO MAKE A LIVING, MAN!’

Also left in a little excerpt about Doyle spending his lunch money on books {FUCKING NERD (me too)} because I thought it was cute.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#acd canon#acd sherlock holmes#acd sherlock#john watson#dr watson#arthur conan doyle#dr Joseph bell#sherlock holmes analysis

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

As voted by the people, I'm offering my analysis on the Hound of the Baskervilles.

Firstly, and getting this out of the way, I adore the Hound of the Baskervilles. My chosen area of focus in my Master's Program was Gothic Literature, and this novel hits all of my favorite aspects of the field.

But there's more to it that I've noticed.

Chiefly among them being that most of the novel focuses on Watson, rather than Sherlock Holmes. While yes, it may have been a product of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle being bitter that he was forced to bring Holmes back, for this novel in particular, I think it's brilliant.

It operates under the premise that this Hound, this creature, is a Fairy Tale come to life and stalks the moor to bring death to all of those of the Baskerville family. In this sense, Watson, as he normally is a vehicle for the audience, is also a purveyor of a Legend come to life.

Watson, even if Sherlock Holmes is never quite Gothic, never quite horror, becomes a Gothic protagonist the more he lives in Dartmoor and learns about the family. But he's an evolution of a Gothic protagonist, too.

By the 1890s, the Decadence movement primarily took up the reins of Gothic Literature, creating what we know as fin-de-siecle, or the turn of the century. Many protagonists of this age fell to sin, corruption, and hedonism, such as the case of Dorian Gray.

(I find it fitting to use Dorian Gray, as Oscar Wilde and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle met over a meal that lead to the creation of both A Study in Scarlet and the Picture of Dorian Gray.)

But Watson? He remains steadfast in his nature. He never falls to the era defining corruption and sin, and, even evolves in his deductive reasoning when he finally finds and reunites with Holmes towards the end of the novel.

Even still, he still is, a Gothic protagonist, alongside Sir Henry. They navigate the Baskerville home on the Moor, a crumbling, haunted place, ripe with ancestral sin.

That is what defined the time, even if Watson never falls to sin and corruption. Decadence and fin-de-siecle were defined by all things falling to sin, decay, and rot. What was once glamorous and majestic of the preceding Aesthetic movement had rotted away, underneath.

And, given that Holmes and Watson reunite towards the end of the novel, they yet again defy the era's expectation of Gothic Literature. Their presence is hope, a light in the corruption that drags at the Baskerville family name. While by definition, perhaps a deus ex machina, it works brilliantly.

After all, who else could you go to, when there's a beast of legend killing your family?

As for the Hound itself. It alone is one of the greatest images of late Gothic horror I know. A coal black hound, muzzle shrouded in flame and phosphorous and snapping at your heels... it indeed installs primal, Gothic terror. It makes you ask, what's real? What's not? Can I even trust my reality anymore?

And it's also something that Holmes, for all of his brain and power of the mind, does not know. It invokes a sense of delicious, morbid terror, that while amazed, our detective is just as in the dark as we are before the Hound is killed. And it again, creates another layer of vulnerability that we don't normally get to see.

Lastly, the Hound is also fantastic in invoking the Black Dog Fairy Tales of Europe and beyond. A lot of cultures have a tale, from the Cu-Sith of the Celts, to the Black Dogs roaming England. It strikes fear, because it is used as one of the bases for what we form logic around, as Fairy Tales and folklore so often do for children throughout history.

Perhaps Stapleton knew about this, and preyed upon it on purpose? It's fascinating to think about.

All in all, this is why I adore this novel. Gothic Literature, character evolution, and Fairy Tales...? It's brilliant.

#acd holmes#acd canon#the hound of the baskervilles#Sherlock Holmes analysis with Clear#sherlock holmes#john watson#gothic literature#Seriously I love love love this story#And I hope you do too.

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've started to write an analysis of the Sherlock Holmes Canon under the view of my headcanon and the relationship between Holmes and Watson. It will be a rather lengthy essay, I fear...

I just wanted to know :

Would some of you care to read it once I have finished? (which will take quite some time)

__________

Here we go

https://archiveofourown.org/works/66034900/chapters/170159242

#Ao3#sherlock holmes#holmes and watson#acd canon#john watson#watmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#holmes#holmesian#Acd Canon analysis#Acd headcanon#Canon analysis

79 notes

·

View notes