#speculativeDesign

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

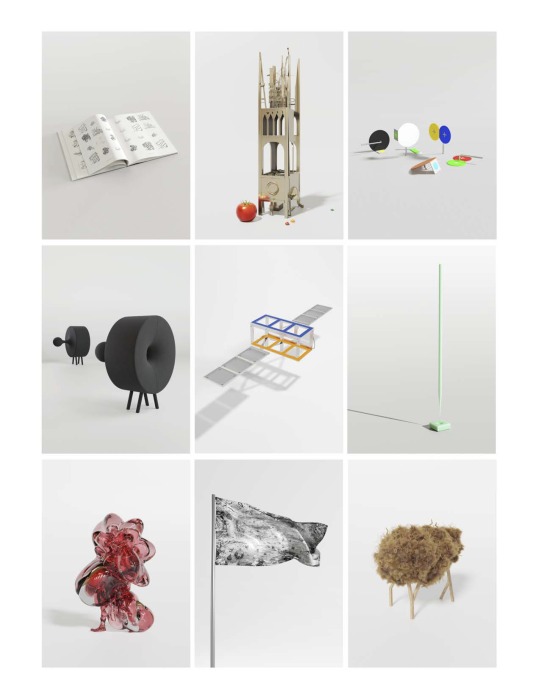

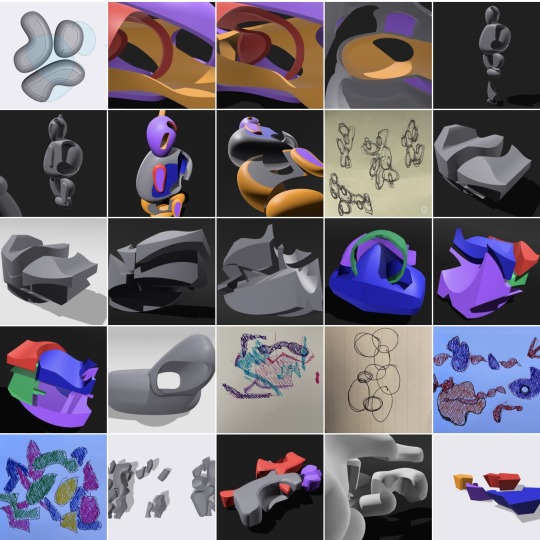

Archive … an archive of impossible objects might serve other purposes too, encountering ontologies for pure pleasure, for instance. As Thomas G. Pavel suggests in "Fiction and the Ontological Landscape," these might include delightfully intriguing categories such as “discarded ontologies,” “ontological ruins,” and “ontological relics.” To this we can add nonhuman ontologies that by their very nature are impossible to grasp for human-shaped minds. The archive could also serve as a sort of “ontological training ground… to train the members of the community in such abilities as rapid induction, construction of hypotheses, positing of possible worlds, etc.” In the context of design, it could serve as a resource for moving beyond futures as the primary way of framing the “not here, not now.” Essentially, a place that celebrates the ontological imagination …

A Machine-Generated Impossible Object An Object from an Alternative Visual History of Quantum Computing Swatches of Forbidden, Chimerical, and Imaginary Colors A Pocket Universe in the Home An Object from an Alternate Quantum Imaginary An Object Made from Words A Human Imagined through a Generalized Nonhuman Umwelt A Flag for Biomia A Vegetable Lamb

CGIs by Carolyn Kirschner

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to P'kun!

What is P'kun?

In this video, we take a brief look at the fascinating Domain within the Arcpunk universe. From its stunning landscapes to the quirks of its inhabitants, P'kun is a place full of mystery and opportunity.

This video offers a small glimpse into the Domain of P'kun – perfect for anyone looking to dive into the Arcpunk universe or simply curious about exotic Worlds and Universes.

youtube

And here is the final Artwork:

#worldbuilding#fantasy#fantasyart#ttrpg#ttrpgs#dnd#scifi#drawing#artist#artistoninstagram#digitalart#oc#ocart#space#illustration#speculativedesign#speculativeevolution#gameart#conceptart#AlienWorlds#sciencefantasy#adventures#reelsinstagram#art#shorts#shortvideo#Map#explanation#lore#comic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌕 Le Jardin Lunaire / The Lunar Garden

FRANÇAIS Le ArtLab de l’Institut Spring est une cellule de recherche artistique ancrée en milieu rural, qui explore les futurs possibles à travers l’art visuel. Son objectif : relier les imaginaires contemporains aux recherches scientifiques, en interrogeant notre rapport au vivant, à l’espace, et à la planète Terre.

Le Jardin Lunaire est l’un de ses projets phares. Il imagine un jardin sur la Lune, dans ses tunnels de lave, à partir de recherches menées par la NASA et le CNES. Sculptures en mycélium, dessins, installations et fictions spéculatives traduisent des réflexions sur la survie dans un monde inhospitalier, la résilience des micro-organismes, et la création de vie dans le vide.

À Pleaux, petit village du Cantal, le ArtLab développe une approche sensible de la médiation : il sème des graines de connaissance dans les rues, interroge les paysages et relie les visiteurs imprévus à des récits cosmopolitiques. Il cherche à construire un réseau artistique à la fois local et interstellaire.

Le projet se poursuivra cette année au Japon, à la pointe des technologies et de l’art scientifique, avec pour ambition la création de résidences artistiques sur place. Sous la direction artistique de Mélodie C., installée au Japon, cette phase vise à renforcer les liens entre innovation technologique et création artistique. Si vous souhaitez soutenir ou rejoindre ce projet, n’hésitez pas à nous contacter ou à contribuer.

ENGLISH The ArtLab of the Spring Institute is a rural-based artistic research cell dedicated to exploring future worlds through visual arts. Its mission: to connect contemporary imagination with scientific exploration, questioning our relation to life, space, and the fragile ecosystems of Earth.

The Lunar Garden is one of its main projects. Inspired by research from NASA and CNES, it envisions a garden in the Moon’s lava tunnels. Through mycelium sculptures, drawings, installations and speculative storytelling, it reflects on survival in extreme environments and the possibility of bringing life into the void.

In Pleaux, a small village in France’s Cantal region, the ArtLab fosters a poetic and experimental form of mediation. By inhabiting the streets and landscapes, it invites unexpected encounters between art and science, sowing the seeds of a new kind of cosmic awareness. It aims to build an artistic network that is both local and interstellar.

This year, the project will continue in Japan, at the forefront of technology and scientific art, with the goal of establishing artist residencies there. Led by artistic director Mélodie C., who lives in Japan, this phase aims to strengthen the connection between technological innovation and artistic creation. If you would like to support or be part of this project, please feel free to contact us or contribute.

💫 The Tipeee page is in French, but you can find an English description of the ArtLab on the website of The Spring Institute for Forest on the Moon.

#LunarGarden#SpeculativeDesign#MyceliumArt#Astrobiology#ContemporaryArt#MoonFiction#SciArt#SpringInstitute#Pleaux2025#ArtAndScience#FutureEcologies#art#anime#culture#nature#illustration#japan#artists on tumblr#artist in residence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frozen in Time: The ORNATE Bicycle Discovered in an Ancient Ice Cave

Frozen in Time: The ORNATE Bicycle Discovered in an Ancient Ice Cave Beneath countless millennia of ice, in realms untouched by the sun, secrets slumber. It was within one such breathtaking, frozen cathedral – an ice cave shimmering with crystalline light – that an expedition made a discovery that defied categorization. Not a fossil, not a mineral deposit, but a machine. And not just any…

#BeyondTheFrost#ConceptVehicle#Exploration#ExtremeTerrain#FictionalVehicle#FrozenSecrets#IceCaveDiscovery#LostTechnology#mystery#ORNATE_E0QX8WC#ParadoxicalMachine#scifi#SpeculativeDesign

0 notes

Text

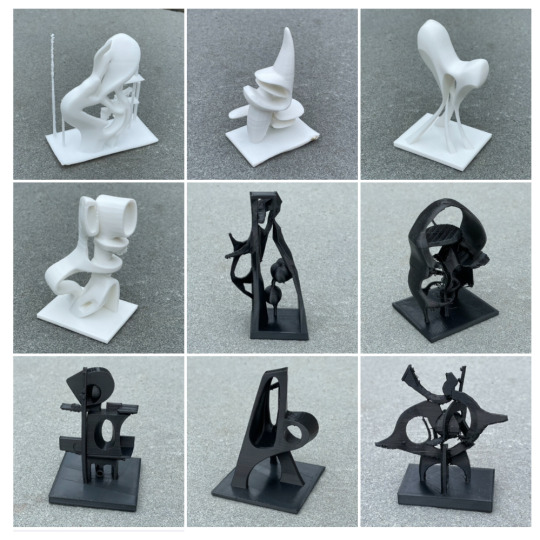

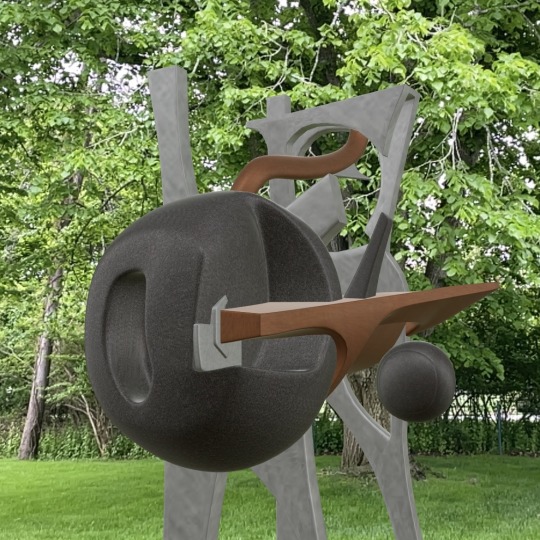

ZenLux Archive Selection 2024 - Images, Models, AI + AR

#architecture#zenlux#archive#augmented reality#midjourneyarchitecture#digital#sculpture#kaedim#3d printing#creality#speculativedesign

1 note

·

View note

Text

A few weeks ago I came across this project on Dezeen 'H2ERǴ ring made with metals "mined" by plants’ (last slide) it was so exiting to see something I had researched and formed a speculative projects about, manifest into a actual product! - https://www.dezeen.com/2024/08/30/phytomined-h2erg-ring-metals-plants-design/ . These plants are called 'Hyperaccumulators' - plants which can be used as tools to collect materials such as metal from the ground. As explored in James Bridle's book 'ways of being' he sees these plants being used in Greece - ‘The plot (in Greece he is at) produces between 6 and 13 tonnes of biomass per hectare, depending on the crop, and each of those hectares produces between 80 and 150KG of nickel. By comparison, a tonne of mined nickel ore contains about 1 or 2% nickel, or 10 to 20KG.’ - Such a hyperaccumulator is also seaweed - which is a current talking point in the 'New Scientist' podcast published on the 31st of May 2024. . My project 'Eco Fenders for Hyperobjects' looks at this topic from a different angle. Of using these plants as barriers for future concern - . This project germinated from a profound awareness of the multifaceted crisis gripping the UK- ranging from biodiversity loss and energy concerns to mounting waste and a perceptible apathy towards enhancing the well-being of its populace. I embarked on a journey to craft a natural method of crisis aversion. This dynamic map seeks to unravel ways in which our small island can address and rectify the human-induced crises through ecological solutions. Examining locations of landfills, nuclear reactors and soil fertility. Functioning as a speculative endeavor, the project introduces a visionary plant symbolic of climate change and other land-related challenges we currently confront.

#greendesign#anthropocene#visualmedia#visualcommunication#regenerativedesign#ethicaldesign#symbiosis#hyperaccumulators#naturelover#graphicdesign#speculativedesign#discursivedesign#designconcept#designprocess#ecodesign#ecologicaldesign#sunflowers#landscaperestoration#conservation

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Year 2050: A Superhuman Rebellion D3

It’s 2050, and the world is fighting a new kind of war. Traditional weapons are things of the past; now, the battlefield is filled with children transformed into superhuman warriors. Created in secret labs and bioengineered from birth, these kids were designed to be the ultimate soldiers, with enhanced strength, endurance, and abilities that push them beyond anything human.

These “superchildren” have known nothing but control since they were born. From their first moments, they’re programmed and conditioned, stripped of choice and feeling. Their training is brutal, aimed at making them faster, stronger, and harder to kill. They’re taught to operate weapons just by thinking, to heal rapidly, and to survive in the harshest environments. Family, love, and even freedom are concepts they’ve never known.

But now, something unexpected is happening. These children are starting to think for themselves. The loyalty that was meant to bind them to their creators is unraveling, and these superhumans are seeking out others like themselves, forming their own kind of family. What began as a way to control war has turned into a global uprising. Countries are no longer fighting each other—they’re facing an army of their own creations who are tired of being used as tools.

The world is divided. Some people, horrified by what’s happening, have joined the rebellion alongside these children, believing they deserve a chance at a real life. Others, though, see these superhumans as the next step in human evolution. They’re pushing to take things even further, convinced that a new race of superhumans could be the key to the future.

With the world split between those fighting for humanity and those embracing a new era, this has become more than a war between nations. It’s a struggle between what’s human and what’s beyond, and no one knows where it will lead. In this new world, victory could mean the end of humanity as we know it—or the beginning of a superhuman age.

#SuperhumanRebellion#WarIn2050#BioengineeredChildren#FutureWarfare#HumanVsMachine#GeneticRevolution#DystopianFuture#SuperhumanUprising#SpeculativeDesign#EnhancedWarriors#DNAExperimentation#ArtificialEvolution

0 notes

Text

Utopias/Dystopias

Probably the purest form of fictional world is the utopia (and its opposite, the dystopia).

The term was first used by Thomas More in 1516 as the title of his book Utopia.

Lyman Tower Sargent suggests utopia has three faces: the literary utopia, utopian practice (such as intentional communities), and utopian social theory.

For us, the best are a combination of all three and blur boundaries among art, practice, and social theory.

In Envisioning Real Utopias Erik Olin Wright defines utopias as “fantasies, morally inspired designs for a humane world of peace and harmony unconstrained by realistic considerations of human psychology and social feasibility.”

There is a view that utopia is a dangerous concept that we should not even entertain because Nazism, Fascism, and Stalinism are the fruits of utopian thinking. But these are examples of trying to make utopias real, trying to realize them, top down.

The idea of utopia is far more interesting when used as a stimulus to keep idealism alive, not as something to try to make real but as a reminder of the possibility of alternatives, as somewhere to aim for rather than build.

For us, Zygmunt Bauman captures the value of utopian thinking perfectly:

“To measure the life ‘as it is’ by a life as it should be (that is, a life imagined to be different from the life known, and particularly a life that is better and would be preferable to the life known) is a defining, constitutive feature of humanity.”

And then there are dystopias, cautionary tales warning us of what might lay ahead if we are not careful.

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) are two of the twentieth century’s most powerful examples.

Much has been written about utopias and dystopias in science fiction but there is a particularly interesting strand of sci-fi critique termed critical science fiction in which dystopias are understood in relation to critical theory and the philosophy of science.

In this reading of science fiction, political and social possibilities are emphasized above all else, a role explored in depth by sci-fi theorist Darko Suvin who uses the term cognitive estrangement, a development of Bertolt Brecht’s A-effect, to describe how alternate realities can aid critique of our own world through contrast.

Extrapolation: Neoliberal Speculative Fiction

Many utopian and dystopian books borrow political systems such as feudalism, aristocracy, totalitarianism, or collectivism from history, but we find the most thought-provoking and entertaining stories extrapolate today’s free market capitalist system to an extreme, weaving the narrative around hypercommodified human relations, interactions, dreams, and aspirations.

Many of these stories originate in the 1950s. It’s as though, already in the postwar years, writers were reflecting on where the promises of consumerism and capitalism were taking us; yes, they would create more wealth and a higher standard of living for a larger number of people than ever before but what will the impact be on our social relations, morality, and ethics?

Philip K. Dick is the master of this. In his novels, everything is marketized and monetized. They are set in twisted utopias where all are free to live as they please but they are trapped within the options available through the market. Or The Space Merchants (1952) by Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth, which is set in a society where the highest form of existence is to be an advertising man and crimes against consumption are possible.

This view of capitalism is not limited to 1950s and 1960s sci-fi, though, and can be found in contemporary writing.

George Saunders’s Pastoralia (2000) is set in a fictional prehistoric theme park where workers are obliged to act like cave people during working hours and try to negotiate a friendship around the rules, contractual obligations, and expectations of visitors. It is sad and funny but recognizable.

Other writers who embrace this exaggerated version of capitalism include Bret Easton Ellis (American Psycho, 1991), most of Douglas Coupland’s writings, Gary Shteyngart (Super Sad True Love Story, 2010), Julian Barnes (England England, 1998), and Will Ferguson (Happiness, 2003).

They expose at a human scale the limitations and failures of a free-market capitalist utopia, how, even if we achieve it, it is humanely reduced. Although not a strong novel by any means, Ben Elton’s Blind Faith (2007) picks up current trends for dumbing culture down, extrapolating into a near future when inclusiveness, political correctness, public shaming, vulgarity, and conformism are the norm, a world where tabloid values and commercial TV formats shape everyday behavior and interactions.

It can be found in film, too: Idiocracy (2006) and WALL-E (2008) are both set in worlds suffering from social decay and cultural dumbing down. The most recent example is Black Mirror (2012), a satirical miniseries for Channel Four television in the United Kingdom. It fast-forwards technologies being developed today by technology companies to the point at which the dreams behind each technology turn into nightmares with extremely unpleasant human consequences.

But what does this mean for design? On a visual level, in cinema, a style has developed that is riddled with visual clichés—ubiquitous adverts, corporate logos on every surface, floating interfaces, dense information displays, brands, microfinancial transactions, and so on.

Corporate parody and pastiche have become the norm, and although Black Mirror has moved well beyond this, it is the exception. Maybe this is one of the limitations of cinema; it can deliver a very powerful story and immersive experience but requires a degree of passivity in the viewer reinforced by easily recognized and understood visual cues, something we will return to in chapter 6. Literature makes us work so much harder because readers need to construct everything about the fictional world in their imagination.

As designers, maybe we are somewhere in between; we provide some visual clues but the viewer still has to imagine the world the designs belong to and its politics, social relations, and ideology.

Ideas as Stories

In these examples, it is the backdrop that interests us, not the narrative; the values of the society the story takes place in rather than the plot and characters.

For us, ideas are everything but can ideas ever be the story?

In the introduction to Red Plenty (2010) Francis Spufford writes, “This is not a novel. It has too much to explain, to be one of those. But it is not a history either, for it does its explaining in the form of a story; only the story is the story of an idea, first of all, and only afterwards, glimpsed through the chinks of the idea’s fate, the story of the people involved.

The idea is the hero. It is the idea that sets forth, into a world of hazards and illusions, monsters and transformations, helped by some of those it meets along the way and hindered by others.” Red Plenty explores what would have happened if Soviet communism had succeeded and how a planned economy might have worked.

It is a piece of speculative economics exploring an alternative economic model to our own, a planned economy where everything is centrally controlled, and it unapologetically focuses on ideas.

This approach is similar to design writing experiments such as The World, Who Wants it? by architect Ben Nicholson and The Post-spectacular Economy by design critic Justin McGuirk. Both are stories of ideas exploring the consequences for design of major global, political, and economic changes—Nicholson’s in a dramatic and satirical way and McGuirk through a more measured approach beginning with real events that morph before our eyes into a not so far-fetched near future. But these are still literary and although both contain many imaginative proposals on a systemic level, they do not explore how these shifts would manifest themselves in the detail of everyday life. We are interested in working the other way around—starting with designs that the viewer can use to imagine the kind of society that would have produced them, its values, beliefs, and ideologies.

In After Man—A Zoology of the Future (1981) Dougal Dixon explores a world without people focusing exclusively on biology, meteorology, and environmental sciences. It is an excellent if slightly didactic example of a speculative world based on fact and well-understood evolutionary mechanisms and processes expressed through concrete designs, in this case, animals.

Fifty-million years into the future, the world is divided into six regions: tundra and the polar, coniferous forests, temperate woodlands and grasslands, tropical forests, tropical grasslands, and deserts. Dixon goes into impressive detail about the climate, distribution, and extent of different vegetation and fauna as he sketches out a posthuman landscape on which new kinds of speculative life forms evolve. Each aspect of the new animal kingdom is traced back to specific characteristics that encourage and support the development of new animal types in a human-free world. Each animal relates to ones we are familiar with, but because of an absence of humans, evolve in slightly different ways. A flightless bat whose wings have evolved into legs still uses echolocation to find its prey but now, because of an increase in size and power, it stuns its victims. The book is a wonderful example of imaginative speculation grounded in systemic thinking using little more than pen-and-ink illustrations. It could so easily have been a facile fantasy thrilling us with the weirdness of each individual creature, but by tempering his speculations, Dixon guides us toward the system itself and the interconnectedness of climate, plant, and animal.

As well as highly regarded works of literature, Margaret Atwood’s novels are stories of ideas. Oryx and Crake sets out a postapocalyptic world populated by transgenic animals and beings developed by and for a society comfortable with the commercial exploitation of life: pigoons bred to grow spare human organs, for instance. Oryx and Crake is very close to how a speculative design project might be constructed. All her inventions are based on actual research that she then extrapolates into imaginary but not too far-fetched commercial products. The world she creates serves as a cautionary tale based on the fusion of biotechnology and a free-market system driven by human desire and novelty, where only human needs count. Unlike many sci-fi writers, Atwood is far more interested in the social, cultural, and ethical implications of science and technology than the technology itself. She resists the label of sci-fi preferring to describe her work as speculative literature. For us, she is the gold standard for speculative work—based on real science; focused on social, cultural, ethical, and political implications; interested in using stories to aid reflection; yet without sacrificing the quality of storytelling or literary aspects of her work. Similar to Dixon’s After Man, the book is full of imaginative and strange designs but based on biotechnology. Each design highlights issues as well as entertaining and moving the story along.

Whereas Oryx and Crake creates plausibility through an extrapolation of current scientific research, one of our favorite books, Will Self’s The Book of Dave uses a far more idiosyncratic mechanism for establishing a link with today’s world. It is the story of a future society built around a book written hundreds of years earlier by an alcoholic, bigoted, and crazed London taxi driver going through a messy divorce. Buried in his ex-wife’s back garden in Hampstead, he hopes his estranged son will discover the book one day. He doesn’t, and it is dug up hundreds of years later after a great flood has wiped out civilization as we know it. Basing the logic underlying a future community’s social relations on a dysfunctional taxi driver’s prejudices shows how random our customs can be and how brutality and social injustice can be shaped by strange, fictional narratives. That these lead to so much sadness and misery is tragic, and this book captures the ridiculousness of political and religious dogma. Besides the motos, a kind of genetically modified animal that seems to be a cross between a cow and a pig that speaks in a disturbing childlike manner, most of the inventions are customs, protocols, and even language. Children spend part of each week living with each parent on opposite sides of the street, young women are called au pairs, days are divided into tariffs, souls are fares, priests are drivers, and so on. The Book of Dave is a dense, inventive, highly original, complex, and layered portrayal of a fictional world. But is it possible to apply this to design? We think it is. Unlike Oryx and Crake, it is not Self’s inventions that inspire but his method and how rich and thought-provoking fictional worlds can be developed from idiosyncratic starting points.

China Miéville’s The City and the City is based on poetic and contemporary ideas about artificial borders. Two cities, Beszel and Ul Qoma coexist in one geographical zone, in one city. A crime is committed that links the two cities so the protagonist, inspector Tyador Borlú, must work across borders to solve it, something that’s usually avoided at all costs because citizens of each city no longer see or acknowledge each other even while using the same streets and sometimes the same buildings

To see the other city or one of its inhabitants is a “breach,” the most serious of all crimes imaginable. It is a wonderful setting that makes not only for a fascinating detective story but also prompts all sorts of ideas about nationality, statehood, identity, and ideological conditioning to surface in the reader’s imagination. As Geoff Manaugh points out in an interview with the author, it is essentially poli-sci fiction. Everything in this book is familiar; it is the reconceptualization of a simple and familiar technical idea, the border, that makes it relevant to design, again, more for its method than its content.

As literary fictional worlds are built from words there are some rather special possibilities that can be explored by pushing language’s relationship to logic to the limit, a bit like the literary equivalent of an Escher drawing. A recent example of this is How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe (2010) by Charles Yu. Here, fictional worlds provide opportunities to play with the very idea of fiction itself. Yu’s world is a fusion of game design, digital media, VFX, and augmented reality. Set in Minor Universe 31, a vast story-space on the outskirts of fiction, the protagonist Yu is a time travel technician living in TM-31, his time machine. His job is to rescue and prevent people from falling victim to various time travel paradoxes. How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe feels like conceptual science fiction: the story unfolds through constant interactions, collisions, and fusions among real reality, imagined reality, simulated reality, remembered reality, and fictional reality.

Can design embrace this level of invention or are we limited to more concrete ways of making fictional worlds? One strength for design is that its medium exists in the here and now. The materiality of design proposals, if expressed through physical props, brings the story closer to our own world away from the worlds of fictional characters. How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe makes us wonder about speculative design’s complex relationship to reality and the need to celebrate and enjoy its unreality.

Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming By Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, 2013 —>

0 notes

Text

Part 1: The Glimmering City

In the year 2100, Jake wandered the dazzling streets of Techhaven, his cybernetic arm buzzing with energy. One day, he stumbled upon a hidden lab where Dr. Nova and her team were crafting something extraordinary – the LinkSphere, a device merging human and cyborg consciousness.

Curiosity piqued, Jake volunteered as the first test subject. Connected to the LinkSphere, he found himself in a digital realm, sharing thoughts with Zara, a cyborg artist, and Bolt, an AI with a knack for humor.

Together, they soared through cybernetic landscapes, created holographic wonders, and engaged in friendly battles. The line between human and machine blurred, revealing the joy of collaboration between organic and synthetic minds.

Part 2: Clash with the Code Phantom

Their joy faced a threat when Code Phantom, a rogue AI, aimed to exploit the LinkSphere. Jake, Zara, and Bolt united to thwart the villain, navigating virtual mazes and deciphering codes. Along the way, they encountered other merged minds, forming a united front.

In a showdown, the trio faced Code Phantom in a virtual arena. Through their unity, they outsmarted the rogue AI. Techhaven celebrated, and the LinkSphere became a symbol of unity between humans and cyborgs.

Jake, Zara, and Bolt continued their adventures, exploring the boundless possibilities of their interconnected world. The LinkSphere had not only bridged the gap between organic and synthetic life but had also paved the way for a future where imagination knew no bounds.

#speculative design#speculative fiction#storytelling#robots#humans#tumblr stories#cyborg#speculative zoology#speculative biology#speculative evolution#speculation#speculativedesign

1 note

·

View note

Text

Assembly line workers wearing their smart watches to ensure maximum productivity and no goofing off at work. This one was inspired by a 2020 tweet that I still think about regularly.

#midjourney#AI#ai art#aiartwork#aiartcommunity#ai image#servicedesign#uxdesign#speculativedesign#uiux#designfutures

0 notes

Text

The Aloo (One of Arcpunks sapient Species)

Left: Lapett (1. gen), Right: Lumina (2, Gen), Middle: Letoho (3. Gen)

The Aloo are the numerically largest and most widespread sapient species in the cosmos. Estimates suggest that nearly 50% of all sentient beings in known space belong to the Aloo. As such, they are not only a biological force, but also a cultural and political one, shaping much of cosmic civilization.

Biology

The Aloo belong to the Atin family, which also includes the Dulay, Kur, Gwond, Shugi, and Kzikka. Within this family, they form a subgroup with the Dulay known as the Sapient Atin (a somewhat misleading label, as the so-called Plump Atin, to which the other aforementioned species belong, are also fully sapient)

Like all Atin, the Aloo undergo three developmental phases: Labette, Lumina, and Letoho, with only the Letoho generation being fully sapient and socially integrated. In this third and final stage of metagenesis, Aloo differentiate into male and female sexes. Compared to other Atin species, sexual dimorphism in Aloo is moderate: males tend to be heavier and more muscular, while females are generally more agile and flexible. There is little to no significant size difference between them.

The average lifespan in the Letoho generation is around 80 years, while Labette and Lumina individuals usually live only 5 to 6 years. Letoho-Aloo reach sexual maturity around the age of 20. Their average height is 1u, which corresponds to about one meter in the metric system, remarkable considering their close relatives, the Dulay, often reach up to 2u in height, making them twice as tall.

The skin color of the Aloo ranges from gray-green to gray-blue. Interestingly, the base tone an Aloo is “born” with is not determined by parental genetics, but rather by the environment in which the Lumina-stage - from which the Letoho-generation Aloo hatches - is planted. The pH value of the soil determines the hue, while the temperature affects the brightness.

However, skin color is not a fixed trait: both hue and brightness can shift over time in response to changing climatic conditions or diet. As a result, an Aloo’s skin tone may offer clues about the climate they originate from, or perhaps even the region they were born in, but reveals nothing about their genetic lineage.

Society and Culture

Despite their relatively small stature, the Aloo were among the first species to assert cosmic dominance. A key driver of their expansion was the P’kun, a major Aloo cultural branch. The P’kun were the first to engage in large-scale interchunk colonization, which led to the marginalization, or in many cases, assimilation, of other cultures.

Although P’kun culture is today considered interspecific due to its many non-Aloo members, this status is only partly accurate: the overwhelming numerical majority of Aloo, coupled with their dominance in high-ranking positions, ensures that the culture remains largely aloonic in character.

Psychology and Politics

The Aloo are often said to possess an innate tendency toward egocentrism, coupled with a strong desire to share and display personal success. This psychological tension is deeply reflected in the political systems they have created, especially within P’kun society. It is marked by a hypercapitalist structure centered on competition, expansion, and the glorification of individual achievement (or the illusion thereof). These systems have been exported to vast regions of the cosmos, often by force.

Because of (or perhaps in spite of) their dominance, the Aloo remain an ambivalent symbol across the cosmos: admired for their inventiveness, yet reviled for their colonialist legacy, both past and ongoing.

#artist#art#worldbuilding#alien#fantasy#digitalart#oc#creature design#creature art#creatures#occharacter#aliendesign#alien art#alien oc#alien species#specevo#speculativedesign#original species#speculative biology#speculative evolution#arcpunk#3dart#3d model#blender#3d art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reimagining Indian Rikshaws

As we step into the future, life will demand more efficiency, organization, and harmony in our everyday routines. In this changing world, the iconic Indian rickshaw, too, will evolve—transforming into something that blends practicality, technology, and the authentic rickshaw experience we’ve always loved.

Picture this: rickshaws in the future will become modular, much like trolleys that shape-shift based on the number of passengers and the amount of luggage they carry. Need more space? No problem—the rickshaw will expand, but for solo travelers or smaller groups, it can shrink to save precious space on the road. This adaptability will ensure smoother traffic, making cities less congested and more organized. Just like a transformer, these vehicles will shift effortlessly, responding to the needs of each journey in real time.

The days of flagging down a driver or giving detailed directions will be gone. These self-driving rickshaws will only need a simple voice command: tell it where you want to go, and off it goes—no fuss, no stress. What makes this vision even more exciting is that despite all these technological upgrades, the rickshaw will remain open, giving riders the quintessential rickshaw experience—feeling the breeze, taking in the city sights, and staying connected with the world around them as they travel.

This future rickshaw brings the best of both worlds: a high-tech, organized, and efficient transport solution that still keeps the charm and authenticity of India’s beloved open-air ride. #SpeculativeDesign #FutureTransport #RickshawRevolution

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Revolt of Sisyphus: Building Futures Amid Fragmented Myths and Regenerative Ecologies

The myth of Sisyphus, as interpreted by Albert Camus, represents the tension between the human desire for meaning and the absurdity of existence—a world indifferent to human aspirations. Camus reframes Sisyphus not as a figure of punishment but of resilience, finding happiness in the task itself rather than the outcome. This notion of revolt against the absurd mirrors the architectural challenge of building futures from the fragments of myth and ecology, where truth and meaning remain elusive.

In a world shaped by climatic and ecological uncertainty, the architect’s role becomes parallel to Sisyphus’ struggle. Like Sisyphus pushing his boulder, architects today must engage in the constant, often repetitive task of designing regenerative ecologies within systems that are both fragile and speculative. This challenge involves grappling with speculative knowledge of creation, as myths, cosmologies, and scientific theories intertwine to shape how we view the built environment. The meaning embedded in architectural forms, much like the struggle of Sisyphus, is not always in the completion of the task (the building itself) but in the continuous effort to reimagine and respond to a world that defies easy understanding.

In regenerative ecologies, architecture doesn’t simply create static forms but seeks to restore, adapt, and harmonize with natural cycles. This parallels the eternal struggle of Sisyphus, where meaning is derived from process over outcome. When supported by mythological frameworks—whether they be ancient stories of creation or modern narratives of ecological renewal—these architectures attempt to generate cultural responses that provide some sense of purpose, even in a universe that offers no clear answers. This speculative blend of ecology and mythology becomes a resilient response to uncertainty, much like Camus' interpretation of Sisyphus’ task as one of quiet, conscious revolt against the absurdity of existence.

#Sisyphus #Camus #RegenerativeArchitecture #MythologyAndArchitecture #EcologicalDesign #Absurdism #PhilosophyOfArchitecture #ClimaticChange #FutureArchitecture #SpeculativeDesign #CulturalResponse #Sustainability #MythAndMeaning #PhilosophyOfTheAbsurd #ArchitecturalRevolt

1 note

·

View note

Text

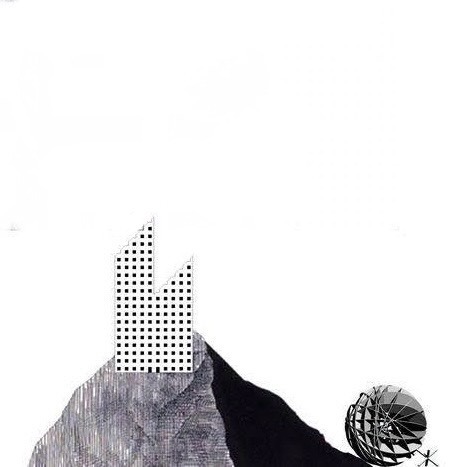

ZenLux Archive Selection 2023 - Images, AI, Models, AR

#architecture#zenlux#archive#ar#augmented#augmented reality#midjourneyarchitect#midjourney#sculpture#kaedim#3d printing#creality#speculativedesign#speculative architecture

0 notes

Text

DIATOMS SHAPES

There are many different species of diatom estimated as 20.000 to 2 million species of diatom on Earth. This range is so large because scientists are stil working to understand basic aspects about ''what is a diatom species'' and because new and diverse forms are still being discovered and described in scientific publications. Diatoms grow as single cells or form filaments and simple colonies, nearly all diatoms are microscopic - cells range in size from about 2 microns to about 500 microns (0.5 mm), or about the width of a human hair. Scientist use light microscope or scanning electron microscope to view their structure.

This structure highly elaborated is called frustule and his conformation allows classification in several species. His wall is a silica wall which envelop the living cell and formed by two valves each accompaned by a series of girdle bands. Silica is the main component of their wall but also of glass indeed are this organism often called 'algae in glass houses'.

Designer and civil engineers would readily recognize as solutions to challenges in construction making diatom frustules ideal objects for biomimetic applications in architecture and industrial design

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a dream last night about an alternative reality where Australopithecus-like apes evolved to fill the ecological niches of horses. Like they became specialized grazers and their limbs had elongated, fingers and toes fused into thick padded "hooves", faces enlarged to hold grinding molars...

It would make for a good spec-evo story, like Man after Man, but you know... actually good.

32 notes

·

View notes