#the application needed us to make a sample spreadsheet for budgeting an event

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

on our volunteering board application

made in google sheets :3

-cas & vio

#my art#art#google sheets#hatsune miku#miku hatsune#shitpost#vocaloid#guys were so getting in#trust#the application needed us to make a sample spreadsheet for budgeting an event#needless to say#miku

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

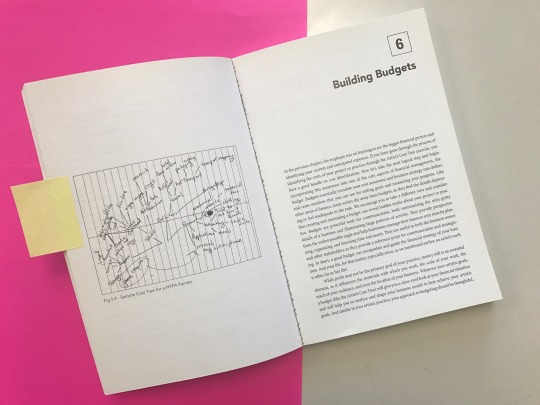

Building a Project Budget

Creating a good budget does not have anything to do with liking math or being a numbers person. It is a form of storytelling.

Just like a 60-second elevator pitch or a 500-word narrative, a project budget is a tool for communication. It is an incredibly useful tool for helping individual artists conduct their practices within financial limits. Project budgets are also a way to share information with a grant review panel, potential donors, and other team members. Creating a strong project budget simply requires artists to present the hard work they are already doing in a new format.

What is a Project Budget?

A project budget is a specific amount of money allocated for a particular purpose over a specific period of time. Project budgets are different from operational budgets, which track the annual income and expenses of an entire organization. Examples of projects include curating an exhibition, directing a short film, or creating a site-specific piece of theatre.

Revise Revise Revise

Since the needs of all projects change over time, revision is an essential component of budgeting. Artists are already pros at making changes to their creative work. This same skillset can be applied to budgeting. By drafting a budget early in a project’s planning process and then periodically assessing and adjusting the budget in accordance with new expenses and funding opportunities, the budget evolves alongside the project. Having an up-to-date project budget on hand makes it easy to share at a meeting or supply one for a last minute deadline.

Step-by-Step Tips for Project Budget Building

1. Brainstorm Expenses: Begin by considering everything about the project that costs money. Nothing is too small to skip. An artist ‘cost tree’ is a brainstorming tool to help artists gain a comprehensive understanding of expenses associated with their project. Some things to keep in mind:

What are the main expenses?

What specific costs are associated with these primary expenses?

What are are smaller expenses associated with each sub-category?

Remember to pay yourself a stipend or hourly wage! To determine your hourly rate as an artist, check out the formula at the end of this post from Andrew Simonet’s book Making Your Life As An Artist. Simonet is the director and founder of Artists U.

2. Organize Expenses: Group similar types of expenses together to create line items on your budget. For example, plaster, burlap, and buckets could be grouped under a ‘Materials’ category. Depending on your budget template, all of the details and subcategories you captured through brainstorming can be listed in a corresponding ‘Notes’ section, or broken down into separate line items.

3. Assess Sources of Income: Income for a project can be categorized into earned income, unearned income, and in-kind support.

Earned Income - Wages, tips, and salaries you receive from employment. Sales from works of art or tickets to an event are also examples.

Unearned or Contributed Income - Sources other than employment and profit from a business, such as interest from savings and stock dividends. For artists, unearned income can also come in the form of project grants, fellowships, cash prizes, and gifts.

In-Kind Support - Goods and services that are not monetary, such as living accommodations during artist residencies or donations of materials.

4. Assess Status of Income: It is important to note in your budget if income for the project is committed or pending. For example, if you already received a grant for a community engagement project, these funds are committed. If you applied for a cash prize but have not received it, this money is pending. It is appropriate to include and designate which funds are committed and pending.

5. Estimate with Care: Budgeting requires that you make estimates of projected income and expenses. To accurately do so, rely on resources such as past experience, experts in the field, and publicly available information. Be as specific as possible, never underestimate the power of common sense, and remember to make conservative estimates. As The Profitable Artist suggests: Do not underestimate the value of your peers’ advice. All artists have to deal with finances, and it might help to ask a few trusted friends to compare notes on expenses, pricing services, etc.

6. Put It Together: Generally, when submitting a project proposal, the expense and income sides of the budget should balance to zero. If you are applying for a grant, always use the budget format requested by the funder. If you are keeping a budget for your personal records, find a strategy that works well for you. Use a spreadsheet in Excel or Google Sheets to organize information and build formulas within the document. Check out these sample project budgets from the Foundation Center’s Grantspace website.

Your Project Budget

Budgets are adaptive to the creative process and are another method for translating an artist’s idea to funders and project team members. They are excellent tools for conveying objectives, and providing frameworks and timelines for reaching project goals to an audience. When a project is complete, its budget remains a helpful guide for measuring outcomes, evaluating progress, and defining its success.

Looking for more resources? NYFA’s The Profitable Artist is a resource and comprehensive career guide for artists of all disciplines.

Excerpt on Determining an Artist Fee, from Making Your Life as an Artist:

Artists don’t know what our time costs. People ask us to do residencies, workshops, artist talks, etc., and to make our lives sustainable, we need to know our rates.

Take the annual income number you just figured out and divide it by 1,500 to get your hourly rate.

Why 1,500? If you work a “normal” job for a year, you’ll work 2,000 hours (40 hours per week for 50 weeks) Artists don’t have 2,000 hours to earn our living. A lot of our work is piecemeal, a teaching gig here and a day job there, with lots of prep, travel and transition time. And we need more down time than most people to feed our imagination and vision. Artists who earn their living in 1,500 hours find sustainability.

Once you have your hourly rate, multiply it by 8 to get your day rate (8 hours in a work day), and multiply your day rate by 5 to get your week rate.

Here’s an example. Suppose you decide you need to earn $45,000 per year to live without financial panic.

45,000 ÷ 1,500 = $30/hour 30 x 8 = $240/day 240 x 5 = $1200/week

Interested in fundraising through NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship for your next great idea? Our next no-fee application is due June 30, 2017. Learn about our Fiscal Sponsorship program by clicking here.

- Madeleine Cutrona, Program Officer, Fiscal Sponsorship

Images, from top: courtesy of Writing On It All, a fiscally sponsored project by Alexandra Chasin; a cost tree in The Profitable Artist, photo by Amy Aronoff

#business of art#fiscal sponsorship#nyfa fiscal sponsorship#nyfafiscalsponsorship#entrepreneurship#fundraising#money#budgeting

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

radEventListener: a Tale of Client-side Framework Performance

React is popular, popular enough that it receives its fair share of criticism. Yet, this criticism of React isn’t completely unwarranted: React and ReactDOM total about 120 KiB of minified JavaScript, which definitely contributes to slow startup time. When client-side rendering in React is relied upon entirely, it churns. Even if you render components on the server and hydrate them on the client, it still churns because component hydration is computationally expensive.

React certainly has its place when it comes to applications requiring complex state management, but in my professional experience, it doesn’t belong in most scenarios I see it used. When even a bit of React can be a problem on devices slow and fast alike, using it is an intentional choice that effectively excludes people with low-end hardware.

If it sounds like I have a grudge against React, then I must confess that I really like its componentization model. It makes organizing code easier. I think JSX is great. Server rendering is also cool—even if that’s just how we say “send HTML over the network” these days.

Still, even though I happily use React components on the server (or Preact, as is my preference), figuring out when it’s appropriate to use on the client is a bit challenging. What follows are my findings on React performance as I’ve tried to meet this challenge in a way that’s best for users.

Setting the scene

Lately, I’ve been chipping away at an RSS feed app side project called bylines.fyi. This app uses JavaScript on both the back and front end. I don’t think client-side frameworks are horrid things, but I’ve frequently observed two things about the client-side framework implementations I tend to run into in my day-to-day work and research:

Frameworks have the potential to inhibit a deeper understanding of the things they abstract, which is the web platform. Without knowing at least some of the lower level APIs that frameworks rely on, we can’t know what projects benefit from a framework, and which projects are better off without one.

Frameworks don’t always provide a clear path toward good user experiences.

You may be able to argue the validity of my first point, but the second point is becoming more difficult to refute. You might remember a little while ago when Tim Kadlec did some research on HTTPArchive about web framework performance, and came to the conclusion that React wasn’t exactly a stellar performer.

Still, I wanted to see if it was possible to use what I thought was best about React on the server while mitigating its ill effects on the client. To me, it makes sense to simultaneously want to use a framework to help to organize my code, but also restrict that framework’s negative impact on the user experience. That required a little experimentation to see what approach would be best for my app.

The experiment

I make sure to render every component I use on the server because I believe that the burden of providing markup should be assumed by the web app’s server, not the user’s device. However, I needed some JavaScript in my RSS feed app in order to get a toggleable mobile nav to work.

This scenario aptly describes what I refer to as simple state. In my experience, a prime example of simple state are linear A to B interactions. We toggle a thing on, and then we toggle it off. Stateful, but simple.

Unfortunately, I often see stateful React components used to manage simple state, which is a trade-off that’s problematic for performance. Though that may be a vague utterance for the moment, you’ll come to find out as you read on. That said, it’s important to emphasize that this is a trivial example, but it’s also a canary. Most developers—I hope—aren’t going to rely solely on React to drive such simple behavior for just one thing on their website. So it’s vital to understand that the results you’re going to see are intended to inform you on how you architect your applications, and how the effects of your framework choices could scale when it comes to runtime performance.

The conditions

My RSS feed app is still in development. It contains no third party code, which makes for easy testing in a quiet environment. The experiment I conducted compared the mobile nav toggle behavior across three implementations:

A stateful React component (React.Component) rendered on the server and hydrated on the client.

A stateful Preact component, also server-rendered and hydrated on the client.

A server-rendered stateless Preact component which was not hydrated. Instead, regular ol’ event listeners provide the mobile nav functionality on the client.

Each of these scenarios were measured across four distinct environments:

A Nokia 2 Android phone on Chrome 83.

A ASUS X550CC laptop from 2013 running Windows 10 on Chrome 83.

An old first generation iPhone SE on Safari 13.

A new second generation iPhone SE, also on Safari 13.

I believe this range of mobile hardware will be illustrative of performance across a broad spectrum of device capabilities, even if it’s slightly heavy on the Apple side.

What was measured

I wanted to measure four things for each implementation in each environment:

Startup time. For React and Preact, this included the time it took to load the framework code as well as hydrating the component on the client. For the event listener scenario, this included only the event listener code itself.

Hydration time. For the React and Preact scenarios, this is a subset of the startup time. Because of issues with remote debugging crashing in Safari on macOS, I couldn’t measure hydration time alone on iOS devices. Event listener implementations incurred zero hydration cost.

Mobile nav open time. This gives us insight into how much overhead frameworks introduce in their abstraction of event handlers, and how that compares to the frameworkless approach.

Mobile nav close time. As it turned out, this was quite a bit less than the cost of opening the menu. I ultimately decided not to include those numbers in this article.

It should be noted that measurements of these behaviors include scripting time only. Any layout, paint, and compositing costs would be in addition to and outside of these measurements. One should take care to remember that those activities compete for main thread time in tandem with scripts that trigger them.

The procedure

To test each of the three mobile nav implementations on each device, I followed this procedure:

I used remote debugging in Chrome on macOS for the Nokia 2. For iPhones, I used Safari’s equivalent of remote debugging.

I accessed the RSS feed app running on my local network on each device to the same page where the mobile nav toggling code could be run. Because of this, network performance was not a factor in my measurements.

Without CPU or network throttling applied, I began recording in the profiler, and reloaded the page.

After page load, I opened the mobile nav and then closed it.

I stopped the profiler, and recorded how much CPU time was involved in each of the four behaviors listed earlier.

I cleared the performance timeline. In Chrome, I also clicked the garbage collection button to free up any memory that may have been tied up by my app’s code from a previous session recording.

I repeated this procedure ten times for each scenario for each device. Ten iterations seemed to get just enough data to see a few outliers while getting a reasonably accurate picture, but I’ll let you decide as we go over the results. If you don’t want a play-by-play of my findings, you can view the results at this spreadsheet and draw your own conclusions, as well as the mobile nav code for each implementation.

The results

I initially wanted to present this information in a graph, but because of the complexity of what I was measuring, I wasn’t certain how to present the results without cluttering the visualization. Therefore, I’ll present the minimum, maximum, median, and average CPU times in a series of tables, all of which effectively illustrate the range of outcomes I encountered in each test.

Google Chrome on Nokia 2

The Nokia 2 is a low-cost Android device with a ARM Cortex-A7 processor. It is not a powerhouse, but rather a cheap and easily obtainable device. Android usage worldwide is currently around 40%, and though Android device specs vary greatly from one device to the next, low-end Android devices are not rare. This is a problem we must recognize as being one of both wealth and proximity to fast network infrastructure.

Let’s see what the numbers look like for startup cost.

Startup time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin137.2131.234.69Median147.7642.065.99Avg162.7343.166.81Max280.8162.0312.06

I believe it says something that it takes, on average, over 160 ms to parse and compile React, and hydrate one component. To remind you, startup cost in this case includes the time it takes for the browser to evaluate the scripts needed for the mobile nav to work. For React and Preact, it also includes hydration time, which in both cases can contribute to the uncanny valley effect we sometimes experience during startup.

Preact fares much better, taking around 73% less time than React, which makes sense considering how tiny Preact is at 10 KiB sans compression. Still, it’s important to note that the frame budget in Chrome is about 10 ms to avoid jank at 60 fps. Janky startup is as bad as janky anything else, and is a factor when calculating First Input Delay. All things considered, though, Preact performs relatively well.

As for the addEventListener implementation, it turns out that parse and compile time for a tiny script with no overhead is unsurprisingly very low. Even at the sampled maximum time of 12ms, you’re barely in the outer ring of the Janksburg Metropolitan Area. Now let’s have a look at hydration cost alone.

Hydration time

React ComponentPreact ComponentMin67.0419.17Median70.3326.91Avg74.8726.77Max117.8644.62

For React, this is still in the vicinity of Yikes Peak. Sure, a median hydration time of 70 ms for one component isn’t a big deal, but think about how hydration cost scales when you have a bunch of components on the same page. It’s no surprise that the React websites I test on this device feel more like endurance trials than user experiences.

Preact’s hydration times are quite a bit less, which makes sense because Preact’s documentation for its hydrate method states that it “skips most diffing while still attaching event listeners and setting up your component tree.” Hydration time for the addEventListener scenario isn’t reported, because hydration isn’t a thing outside of VDOM frameworks. Next, let’s take a peek at the time it takes to open the mobile nav.

Mobile nav open time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin30.8911.943.94Median43.6214.296.14Avg43.1614.666.12Max53.1920.468.60

I find these figures a bit surprising, because React commands almost seven times as much CPU time to execute an event listener callback than an event listener you could register yourself. This makes sense, as React’s state management logic is necessary overhead, but one has to wonder if it’s worth it for simplistic, linear interactions.

On the other hand, Preact manages to limit its overhead on event listeners to the point where it takes “only” twice as much CPU time to run an event listener callback.

CPU time involved in closing the mobile nav was quite a bit less at an average approximate time of 16.5 ms for React, with Preact and bare event listeners coming in at around 11 ms and 6 ms, respectively. I’d post the full table for the measurements on closing the mobile nav, but we have a lot left to sift through yet. Besides, you can check out those figures yourself in the spreadsheet I referred to earlier on.

A quick note on JavaScript samples

Before moving onto the iOS results, one potential sticking point I want to address is the impact of disabling JavaScript samples in Chrome DevTools when recording sessions on remote devices. After compiling my initial results, I wondered if the overhead of capturing entire call stacks was skewing my results, so I re-tested the React scenario samples disabled. As it turned out, this setting had no significant impact on the results.

Additionally, because the call stacks were truncated, I was unable to measure component hydration time. Average startup cost with samples disabled vs. samples enabled was 160.74 ms and 162.73 ms, respectively. The respective median figures were 157.81 ms and 147.76 ms. I would consider this squarely “in the noise.”

Safari on 1st Generation iPhone SE

The original iPhone SE is a great phone. Despite its age, it still enjoys devoted ownership owing to its more comfortable physical size. It shipped with the Apple A9 processor which is still a solid contender. Let’s see how it did on startup time.

Startup time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin32.067.630.81Median35.609.421.02Avg35.7610.151.07Max39.1816.941.56

This is a big improvement from the Nokia 2, and it’s illustrative of the gulf between low-end Android devices and even older Apple devices with significant mileage.

React performance still isn’t great, but Preact gets us within a typical frame budget for Chrome. Event listeners alone, of course, are blazingly fast, leaving plenty of room in the frame budget for other activity.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t measure hydration times on the iPhone, as the remote debugging session would crash every time I would traverse the call stack in Safari’s DevTools. Considering that hydration time was a subset of the overall startup cost, you can expect that it probably accounts for at least half of the startup time if results from the Nokia 2 trials are any indicator.

Mobile nav open time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin16.915.450.48Median21.118.620.50Avg21.0911.070.56Max24.2019.791.00

React does alright here, but Preact seems to handle event listeners a bit more efficiently. Bare event listeners are lightning fast, even on this old iPhone.

Safari on 2nd Generation iPhone SE

In mid-2020, I picked up the new iPhone SE. It has the same physical size as an iPhone 8 and similar phones, but the processor is the same Apple A13 used in the iPhone 11. It is very fast for its relatively low $400 USD retail price. Given such a beefy processor, how does it deal?

Startup time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin20.265.190.53Median22.206.480.69Avg22.026.360.68Max23.677.180.88

I guess at some point there are diminishing returns when it comes to the relatively small workload of loading a single framework and hydrating one component. Things are a little faster on a 2nd generation iPhone SE than its first generation variant in some cases, but not terribly so. I’d imagine that this phone would tackle larger and sustained workloads better than its predecessor.

Mobile nav open time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin13.1512.060.49Median16.4112.570.53Avg16.1112.630.56Max17.5113.260.78

Slightly better React performance here, but not much else. Strangely, Preact seems to take longer on average to open the mobile nav on this device than its first generation counterpart, but I’ll chalk that up to outliers skewing a relatively small dataset. I certainly would not assume the first generation iPhone SE is a faster device based on this.

Chrome on a dated Windows 10 Laptop

Admittedly, these were the results I was most excited to see: how does an ASUS laptop from 2013 with Windows 10 and an Ivy Bridge i5 of the day handle this stuff?

Startup time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin43.1513.111.81Median45.9514.542.03Avg45.9214.472.39Max48.9816.493.61

The numbers aren’t bad when you consider that the device is seven years old. The Ivy Bridge i5 was a good processor in its day, and when you couple that with the fact that it’s actively cooled (rather than passively cooled as mobile device processors are), it probably doesn’t run into thermal throttling scenarios as often as mobile devices.

Hydration time

React ComponentPreact ComponentMin17.757.64Median23.558.73Avg23.128.72Max26.259.55

Preact does well here, and manages to stay within Chrome’s frame budget, and is almost three times faster than React. Things could look quite a bit different if you’re hydrating ten components on the page at startup time, possibly even in Preact.

Mobile nav open time

Preact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin6.062.500.88Median10.433.090.97Avg11.243.211.02Max14.444.341.49

When it comes to this isolated interaction, we see performance that’s similar to high-end mobile devices. It’s encouraging to see such an old laptop still keep up reasonably well. That said, this laptop’s fan spins up often when browsing the web, so active cooling is probably this device’s saving grace. If this device’s i5 was passively cooled, I suspect its performance might drop.

Shallow call stacks for the win

It’s not a mystery as to why it takes React and Preact longer to start up than it does for a solution that eschews frameworks altogether. Less work equals less processing time.

While I think startup time is crucial, it’s probably inevitable that you’ll trade some amount of speed for a better developer experience. Though I’d strenuously argue that we tend to trade too much toward developer experience than user experience far too often.

The dragons also lie in what we do after the framework loads. Client-side hydration is something that I think is far too often abused, and can sometimes be completely unnecessary. Every time you hydrate a component in React, this is what you’re throwing at the main thread:

Recall that on the Nokia 2, the minimum time I measured for hydrating the mobile nav component was about 67 ms. In Preact—for which you’ll see the hydration call stack below—takes about 20 ms.

These two call stacks aren’t to the same scale, but Preact’s hydration logic is simplified, probably because “most diffing is skipped” as Preact’s documentation states. There’s quite a bit less going on here. When you get closer to the metal by using addEventListener instead of a framework, you can get even faster.

A call stack of event listeners attaching to DOM elements.

Not every situation calls for this approach, but you’d be surprised at what you can accomplish when your tools are addEventListener, querySelector, classList, setAttribute/getAttribute, and so on.

These methods—and many more like them—are what frameworks themselves rely on. The trick is to evaluate what functionality you can safely deliver outside of what the framework provides, and rely on the framework when it makes sense.

A call stack of React firing a click event handler to open a mobile nav.

If this were a call stack for, say, making a request for API data on the client and managing the complex state of the UI in that situation, I’d find this cost more acceptable. Yet, it’s not. We’re just making a nav appear on the screen when the user taps a button. It’s like using a bulldozer when a shovel would be a better fit for the job.

Preact at least strikes the middle ground:

A call stack of Preact firing a click event handler to open a mobile nav.

Preact takes about a third of the time to do the same work React does, but on that budget device, it exceeds the frame budget often. This means opening that nav on some devices will animate sluggishly because the layout and paint work may not have enough time to finish without entering long task territory.

A call stack of a bare event listener opening the mobile nav.

In this case, an event listener is what I needed. It gets the job done seven times faster on that budget device than React.

Conclusion

This is not a React hit piece, but rather a plea for consideration of how we do our work. Some of these performance pitfalls can be avoided if we take care to evaluate what tools make sense for the job, even for apps with a great deal of complex interactivity. To be fair to React, these pitfalls likely exist in many VDOM frameworks, because the nature of them adds necessary overhead to manage all sorts of things for us.

Even if you’re working on something that doesn’t call for React or Preact, but you want to take advantage of componentization, consider keeping it all on the server to start with. This approach means you can decide if and when it’s appropriate to extend functionality to the client—and how you’ll do that.

In the case of my RSS feed app, I can manage this by putting lightweight event listener code in the entry point for that page of the app, and using an asset manifest to put the minimal amount of script necessary in order for each page to work.

Now let’s suppose that you have an app that truly needs what React provides. You have complex interactivity with lots of state. Here are some things you can do to try and get things going a bit faster.

Check all of your stateful components—that is, any component which extends React.Component—and see if they can be refactored as stateless components. If a component doesn’t use lifecycle methods or state, you can refactor it to be stateless.

Then, if possible, avoid sending JavaScript to the client for those stateless components, as well as hydrating them. If a component is stateless, only render it on the server. Prerender components when possible to minimize server response time, because server rendering has its own performance pitfalls.

If you have a stateful component with simple interactivity, consider prerendering/server-rendering that component, and replace its interactivity with framework-independent event listeners. This avoids hydration entirely, and user interactions won’t have to filter through the framework’s state management logic.

If you must hydrate stateful components on the client, consider lazily hydrating components that aren’t near the top of the page. An Intersection Observer that triggers a callback works very well for this, and will give more main thread time to critical components on the page.

For lazily-hydrated components, assess whether you can schedule their hydration during main thread idle time with requestIdleCallback.

If possible, consider switching from React to Preact. Given how much faster it runs than React on the client, it’s worth having the discussion with your team to see if this is possible. The latest version of Preact is nearly 1:1 with React for most things, and preact/compat does a great job of easing this transition. I don’t think Preact is a panacea for performance, but it gets you closer to where you need to be.

Consider adapting your experience to users with low device memory. navigator.deviceMemory (available in Chrome and derived browsers) enables you to change the user experience for users on devices with little memory. If someone has such a device, it’s probable that its processor isn’t so fast either.

Whatever you decide to do with this information, the thrust of my argument is this: if you use React or any VDOM library, you should spend some time investigating its impact on an array of devices. Get a cheap Android device and see how your app feels to use. Contrast that experience with your high-end devices.

Most of all, don’t follow “best practices” if the result is that your app effectively excludes a part of your audience that can’t afford high end devices. Keep pushing for everything to be faster. If our daily work is any indication, this is an endeavor that will keep you busy for some time to come, but that’s OK. Making the web faster makes the web more accessible in more places. Making the web more accessible makes the web more inclusive. That’s the really good work we should all be trying our best to do.

I’d like to express my gratitude to Eric Bailey for his editorial feedback this piece, as well as the CSS-Tricks staff for their willingness to publish it.

The post radEventListener: a Tale of Client-side Framework Performance appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

radEventListener: a Tale of Client-side Framework Performance published first on https://deskbysnafu.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

How to Evaluate Event Technology

Are you using the right tools to achieve event success? In this blog post we’ll review how you can evaluate your event technology stack.

Odd as it may seem, there was a time when event technology didn’t exist. Individuals registered for events via mail-in services, events were advertised completely offline in print ads and magazine ads and—at the end of an event—organizers were left with very little data to make sense of.

Contemporary marketers now rely on an intricate mix of tools (such as marketing automation software, CRMs and event software) that work together in what is called the event technology stack, to achieve successful events. They leverage this event tech stack to build websites that drive registrations, promote their event through email marketing and social media, and gather data at every stage of the event lifecycle.

However, not every mix of tools is the right mix of tools. Some may not fully work with one another, others may rely on the manual exporting and importing of data, and others may have hidden potential just waiting to be unlocked.

In this post we’ll review how event marketers can evaluate their event technology stack to fully unleash the power of their events strategy.

For a step-by-step analysis of your own personal event stack, try the Event Technology Assessment. Just click the button below!

Evaluating Event Technology

Your event is more than just the event day itself. Countless hours go into producing an event both before and after it happens. When analyzing the merits of an event technology it’s important to examine the full event technology lifecycle.

The event lifecycle stages can be broken down into Event Awareness, Event Management, Event Experience and Event Success Measurement.

In the below sections we’ll take a closer look at each of these event lifecycle stages and what event professionals like yourself should keep in mind when evaluating technology to meet the needs of each. We’ll also provide several sample questions that event professionals should ask themselves when considering whether or not their event technology is a good fit for their needs.

Event Awareness

If an event happens in a conference center and no one ever promotes it, does it even make a sound?

Adequately promoting an event is essential for driving registrations and, in turn, event attendance. However, the Event Marketing 2018 Report reveals that generating demand for an event is a common pain point among event organizers.

From building your event website to getting the word out, your technology should provide you with the necessary tools for getting get the job done.

Relevant Questions:

Do you require designers and developers to create or modify your web pages?

Do you incentivize registrants to share promotional codes upon submitting their registration?

Do you use remarketing campaigns to capture contact information of potential registrants who did not finish their registration?

Event Management

Collecting and managing event registrants goes way beyond spreadsheets. Literally.

From ticket types, to dietary restrictions, to job titles, to lead stages—each contact that registers for chock full of data.

Some of this data is more important for providing attendees with a satisfying event experience (e.g. whether a contact prefers a gluten free diet, a vegetarian diet or a surf-and-turf diet) while other data can be critical to the success of your event marketing campaign and, subsequently, the success of your organization as a whole (e.g. whether a contact is a prospect, customer or partner).

An efficient event management technology process should enable organizers to create multiple ticket types, manage contacts data via software integrations, and seamlessly process revenue.

Relevant Questions:

Do you manage different ticket types? For example single-day, multi-day, VIP?

Do you integrate event contact data with a CRM (Customer Relationship Management)?

Do you still find yourself managing event data in spreadsheets?

Event Experience

You can’t have an event without attendees. Well, you can, it just might make for an awkward post-event debrief with the rest of your team.

Whether you are planning an internal training event or a massive customer conference, providing a rich experience is crucial for keeping your attendees engaged, satisfied and coming back for more.

Fortunately, the right event technology stack can help you engage your attendees with tools that cater to networking, in-session polls, a smooth event check-in, an easy to use event agenda, net promoter score surveys and much more.

Relevant Questions:

Do you offer an event app for attendees to use?

Do you send real-time notifications to your attendees during the event?

Do you deploy polls during your event to survey your attendees in real-time?

Event Success Measurement

Forrester Research reports that the average CMO allocates 24% of their budget to events. That’s a huge slice of the fiscal pie. In order to prove that an event is worth the slice, marketers need to be able to proffer meaningful data.

The right event technology stack will enable marketers to pull event revenue numbers, compare cross event KPI’s, and sync data to your CRM to paint a clear picture of how an event fits into a contact’s journey with your organization.

But event success is more than just ROI. That’s why your event technology should be able to connect the dots between email marketing performance, social media engagement, event app engagement, attendee preferences and sponsorship performance so that your next event can be better than the previous one.

Relevant Questions:

Which reporting systems do you use to report your event success?

Which reporting elements do you track and review?

Do you track mobile application engagement KPIs?

Next Steps

Whether it comes to promoting your event, managing your event data, creating a valuable experience for attendees or drawing meaningful conclusions from event analytics, event technology can help marketers to drive the success of their events

Take the free Event Technology Assessment and receive actionable insights on your event strategy. Benchmark how well you promote your event, manage registrations, and report your event success.

from Cameron Jones Updates https://blog.bizzabo.com/how-to-evaluate-event-technology

0 notes

Text

51 Items For Your Professional Career Portfolio + Examples

A well-structured professional career portfolio is one of your best tools in winning job opportunities, plain and simple. This means it’s time to roll up your sleeves and get to work on yours.

One of the most common questions people have is about what to include in a portfolio, so we wanted to list some options for you. Even if you aren’t in need of totally revamping your career portfolio right now, you should keep an eye out below for items you can put together or start collecting for the future. Doing this will make the career portfolio process a whole lot easier.

1. Demonstrate Your Education and Training

This is a crucial step when developing your career portfolio since it establishes high level qualifications that employers will want to see. Regardless of your industry or level of training and/or education, taking time to gather this type of information is helpful for potential employers and for yourself. When you combine this with an effective personal branding strategy you will see big results.

Putting what you have together now will save you time in the long run not only when working on your career portfolio, but when you put together other materials. One mistake that people often make is underestimating the education and training that they already have.

As a matter of fact, we see tons of career portfolio examples that miss out on this and it always ends up costing someone an opportunity somewhere down the line. This is easily the most important piece of an effective job portfolio, so don’t proceed until you’re sure you have everything applicable written down.

function load(e){var t=document.getElementsByTagName(“head”)[0],n=document.createElement(“link”);return n.type=”text/css”,n.rel=”stylesheet”,n.href=e,t.appendChild(n),n}load(‘//unpkg.com/[email protected]’);

Get Your Career Portfolio In Front Of More Potential Employers.

Use our free tool to ensure your career portfolio shows up when employers Google your name.

Get started for free

Even if you haven’t obtained a formalized degree in a specific area, this is a great chance to showcase the steps you’ve taken to master your area of interest in addition to working in the field. Far too often job-seekers will only write down their degree, or be discouraged about a lack of one. Don’t fall into this trap!

As a matter of fact, some of the best ways to differentiate yourself fall outside of your degree. If you’re in a profession where a college degree or certification is required, chances are everyone else who is applying has one too. However, when everyone else doesn’t elaborate about extra experience they’ve gained, you can jump to the front of the line by making sure your professional portfolio has plenty of relevant examples.

Displaying this expertise is a crucial aspect of all professional portfolios, so take some extra time to be sure you aren’t missing anything. If you are switching careers, this section is especially helpful in communicating the ways that you’re preparing for this transition.

Brochures describing training events, retreats, workshops, clinics, lecture series

Certificate of mastery or completion

Charts or lists showing hours or time completed in various areas of study

Evidence of participation in vocational competitions

Grants, loans, scholarships secured for schooling

Licenses

Lists of competencies mastered

Samples from classes (papers, projects, reports, displays, video or computer samples)

Samples from personal studies (notes, binders, products)

Syllabi or course descriptions for classes and workshops

Standardized or formalized tests

Teacher evaluations

Transcripts, report cards

2. Demonstrate Your Work Performance

This section of your career portfolio is critical if you have already entered the workforce. Make sure that you gather as much information about the organization and the work that you provided. Keep track of your contributions and any supporting materials. Holding on to this kind of info not only helps you recall this kind of detail, but makes it much easier to show others what it is you’ve been working on and what that says about you.

Many people share their education and training in their professional career portfolio, but forget the performance aspect. This is how you can differentiate yourself when a hiring manager is viewing a handful of them all at once. They’ve seen every career portfolio example under the sun, so make sure the work experience you list is relevant and conveys the importance of your responsibilities!

Community service projects

Descriptive material about the organization (annual report, brochure, newsletters, articles)

Job descriptions

Logs, list or charts showing general effort (phone calls received, extra hours worked, overtime, volume of e-mail, caseload, transactions completed, sales volumes)

Military records, awards, badges

Employer evaluations or reviews

Examples of problem solving

Attendance records

Letters of reference

Organization charts showing personnel, procedures, or resources

Products showing your leadership qualities (mission statements, agendas, networks)

Records showing how your students, clients, or patients did after receiving your services (evidence showing your impact on the lives and performance of other such as test scores, performance improvement data, or employment and promotion)

Resumes

Samples from (or lists showing) participation in professional organizations, committees, work teams.

Surveys showing satisfaction by customers, clients, students, patients, etc.

Invitations to share your expertise (letters or agreements asking you to train, mentor, or counsel others, invitations to present at conferences or professional gatherings)

Documentation of experience as a consultant. (thank-you letters, products, proposals)

3. Demonstrate Your Data Skills

No matter your industry, use data to your advantage in your career portfolio. While you never want to overwhelm your audience, make a point to save information that supports your claims. Whether these are samples of your work, graphs charts and tables, formal documents or photos from a conference, keep tabs on this type of support. These can also provide the benefit of breaking things up within your career portfolio so it’s not all text. A professional portfolio is being read by someone who is very busy. Making it digestible for them will help yours get some extra attention.

Communication pieces (memos, reports, or documents, a public service announcement.

Writing abilities as demonstrated in actual samples of your writing (articles, proposals, scripts, training materials)

Evidence of public speaking (membership in Toastmasters, photograph of you at podium, speech outline, brochure for your presentation, speaker’s badge or brochure, blurb from the conference.) Also posters, photos, reviews of actual performances (dance, drama, music, story-telling)

Data (graphs, charts, tables you helped to produce, testing results)

Display or Performance materials (actual objects, or illustrations, or posters from displays)

Computer related (data base designed, desktop publishing documents, samples from using the Internet, computer video screen pictures or manuals covers illustrating programs you use)

Formal and technical documents as in grant or loan applications (include proposal cover sheet or award letter), technical manual

4. Demonstrate Your People Skills

Whether you work remotely or are client facing every day, you will at some point need to interact with other humans. Because of this, it’s necessary to show that you’re comfortable working with others in your career portfolio. Here are some simple ways to convey this:

People and leadership skills (projects or committees you share, projects you initiated, photos of you with important people, mentoring programs, proposals, documents or strategies related to negotiation)

Planning Samples (summary of steps, instruments used such as surveys or focus groups)

Problem solving illustrated with various artifacts. Use figures or pictures showing improvements in products, services, profits, safety, quality, or time. Include forms and other paper products used to solve problems

Employee training packets, interview sheets, motivational activities

5. Demonstrate Yours Tools Skills

When job-seekers are wondering what to include in a professional portfolio this is one thing that they often forget as well. Start with taking stock of what kind of tools you use in your current job. What tools will you need to use in your desired job?

Take some time to consider how this applies to you, then get to work on showing examples of your success with the tools specific to your area. Whether you use hammers or excel, gather reference materials that demonstrate your mastery of these tools and include them in your career portfolio! This can also be a great chance to be honest with yourself and identify a few things you might want to brush up on beforehand.

Any artifact which shows technical skills, equipment, or specialized procedures used in your work.

Paper documents or replicas of actual items including: forms, charts, print-outs (such as medical chart, financial statement or budgets, reports, emergency preparedness plan, marketing plan, customer satisfaction plan, inspection or evaluation sheet, financial or budget plans, spreadsheets, charts, official documents)

Performance records (keyboard timing scores, safety records, phone logs, complaint logs, pay stub with hours worked highlighted, any record showing volume, amount, total time, response time, turnaround time, dollars or sales figures, size of customer database, organization chart showing people supervised)

Technical directions, manuals, procedure sheets for specialized work, use of equipment, and detailed processes. This could include: sample pages from manuals, illustrations, technical drawings, blueprints or schematics, photos from the workplace, schematics or directions for tools or equipment, operation or procedure sheet

Photos, video, slide-show, or multi-media presentation showing process or equipment.

Actual items which can be handled in various ways: displayed in person one at a time or part of a display you set up

function load(e){var t=document.getElementsByTagName(“head”)[0],n=document.createElement(“link”);return n.type=”text/css”,n.rel=”stylesheet”,n.href=e,t.appendChild(n),n}load(‘//unpkg.com/[email protected]’);

Get Your Career Portfolio In Front Of More Potential Employers.

Use our free tool to ensure your career portfolio shows up when employers Google your name.

Get started for free

6. The Issue With Career Portfolio Examples

A common request you get from people who want to know what to include in a portfolio is if they can see career portfolio examples. While we do think using a template as a high-level starting point can be helpful for some, we often find that many people fall into a trap once they get their hands on some career portfolio examples. The reason for this is they start to create and work within an existing framework in a way that loses their unique spin.

When you look at something through the eyes of someone else or from a one-size-fits-all viewpoint, this is one of the main disadvantages. When you are trying to create something that shows off what you have to offer as an individual, we always advocate that you do as much of it yourself as you can. If your professional portfolio ends up looking like everyone else’s you’re not going to stand out at all.

Another reason why we discourage you from using someone else’s example as a reference when developing your own professional portfolio is because there really isn’t a right or wrong way to do it. As long as you stick with the items and guidelines we’ve mentioned above, you will be completely fine.

What To Do Now

If you haven’t already, bookmark this page or copy and paste the items above for your reference. These items will guide your efforts when building or tweaking a career portfolio for years to come.

Also, try not to get overwhelmed when you’re starting to think about the first steps towards building an awesome career portfolio. It’s easy to put it off because you feel like a lot is riding on how good it makes you look to potential employers. Try to brush that aside and focus on the things that you do naturally that can help tell the story about who you are and what you do.

Don’t overlook smaller projects that you’ve worked on or events that you’ve participated in. Even you if you don’t end up sharing that information in your career portfolio – it’s better that you keep track of these kinds of mini-experiences so that you have the language and visuals to describe them later on if they do work well with other elements that you decide to include in your professional portfolio.

If you want to learn more about how to take something like your portfolio and tie it together with a personal brand that helps you accomplish your professional goals, sign up for a free BrandYourself account. Our software will guide you step by step through the process of developing an online reputation and personal brand with resources you have (like a career portfolio) and ones you should create.

The post 51 Items For Your Professional Career Portfolio + Examples appeared first on BrandYourself Blog | ORM And Personal Branding.

from WordPress https://glenmenlow.wordpress.com/2018/06/21/51-items-for-your-professional-career-portfolio-examples/ via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

51 Items For Your Professional Career Portfolio + Examples

A well-structured professional career portfolio is one of your best tools in winning job opportunities, plain and simple. This means it’s time to roll up your sleeves and get to work on yours.

One of the most common questions people have is about what to include in a portfolio, so we wanted to list some options for you. Even if you aren’t in need of totally revamping your career portfolio right now, you should keep an eye out below for items you can put together or start collecting for the future. Doing this will make the career portfolio process a whole lot easier.

1. Demonstrate Your Education and Training

This is a crucial step when developing your career portfolio since it establishes high level qualifications that employers will want to see. Regardless of your industry or level of training and/or education, taking time to gather this type of information is helpful for potential employers and for yourself. When you combine this with an effective personal branding strategy you will see big results.

Putting what you have together now will save you time in the long run not only when working on your career portfolio, but when you put together other materials. One mistake that people often make is underestimating the education and training that they already have.

As a matter of fact, we see tons of career portfolio examples that miss out on this and it always ends up costing someone an opportunity somewhere down the line. This is easily the most important piece of an effective job portfolio, so don’t proceed until you’re sure you have everything applicable written down.

function load(e){var t=document.getElementsByTagName("head")[0],n=document.createElement("link");return n.type="text/css",n.rel="stylesheet",n.href=e,t.appendChild(n),n}load('//unpkg.com/[email protected]');

Get Your Career Portfolio In Front Of More Potential Employers.

Use our free tool to ensure your career portfolio shows up when employers Google your name.

Get started for free

Even if you haven’t obtained a formalized degree in a specific area, this is a great chance to showcase the steps you’ve taken to master your area of interest in addition to working in the field. Far too often job-seekers will only write down their degree, or be discouraged about a lack of one. Don’t fall into this trap!

As a matter of fact, some of the best ways to differentiate yourself fall outside of your degree. If you’re in a profession where a college degree or certification is required, chances are everyone else who is applying has one too. However, when everyone else doesn’t elaborate about extra experience they’ve gained, you can jump to the front of the line by making sure your professional portfolio has plenty of relevant examples.

Displaying this expertise is a crucial aspect of all professional portfolios, so take some extra time to be sure you aren’t missing anything. If you are switching careers, this section is especially helpful in communicating the ways that you’re preparing for this transition.

Brochures describing training events, retreats, workshops, clinics, lecture series

Certificate of mastery or completion

Charts or lists showing hours or time completed in various areas of study

Evidence of participation in vocational competitions

Grants, loans, scholarships secured for schooling

Licenses

Lists of competencies mastered

Samples from classes (papers, projects, reports, displays, video or computer samples)

Samples from personal studies (notes, binders, products)

Syllabi or course descriptions for classes and workshops

Standardized or formalized tests

Teacher evaluations

Transcripts, report cards

2. Demonstrate Your Work Performance

This section of your career portfolio is critical if you have already entered the workforce. Make sure that you gather as much information about the organization and the work that you provided. Keep track of your contributions and any supporting materials. Holding on to this kind of info not only helps you recall this kind of detail, but makes it much easier to show others what it is you’ve been working on and what that says about you.

Many people share their education and training in their professional career portfolio, but forget the performance aspect. This is how you can differentiate yourself when a hiring manager is viewing a handful of them all at once. They’ve seen every career portfolio example under the sun, so make sure the work experience you list is relevant and conveys the importance of your responsibilities!

Community service projects

Descriptive material about the organization (annual report, brochure, newsletters, articles)

Job descriptions

Logs, list or charts showing general effort (phone calls received, extra hours worked, overtime, volume of e-mail, caseload, transactions completed, sales volumes)

Military records, awards, badges

Employer evaluations or reviews

Examples of problem solving

Attendance records

Letters of reference

Organization charts showing personnel, procedures, or resources

Products showing your leadership qualities (mission statements, agendas, networks)

Records showing how your students, clients, or patients did after receiving your services (evidence showing your impact on the lives and performance of other such as test scores, performance improvement data, or employment and promotion)

Resumes

Samples from (or lists showing) participation in professional organizations, committees, work teams.

Surveys showing satisfaction by customers, clients, students, patients, etc.

Invitations to share your expertise (letters or agreements asking you to train, mentor, or counsel others, invitations to present at conferences or professional gatherings)

Documentation of experience as a consultant. (thank-you letters, products, proposals)

3. Demonstrate Your Data Skills

No matter your industry, use data to your advantage in your career portfolio. While you never want to overwhelm your audience, make a point to save information that supports your claims. Whether these are samples of your work, graphs charts and tables, formal documents or photos from a conference, keep tabs on this type of support. These can also provide the benefit of breaking things up within your career portfolio so it’s not all text. A professional portfolio is being read by someone who is very busy. Making it digestible for them will help yours get some extra attention.

Communication pieces (memos, reports, or documents, a public service announcement.

Writing abilities as demonstrated in actual samples of your writing (articles, proposals, scripts, training materials)

Evidence of public speaking (membership in Toastmasters, photograph of you at podium, speech outline, brochure for your presentation, speaker’s badge or brochure, blurb from the conference.) Also posters, photos, reviews of actual performances (dance, drama, music, story-telling)

Data (graphs, charts, tables you helped to produce, testing results)

Display or Performance materials (actual objects, or illustrations, or posters from displays)

Computer related (data base designed, desktop publishing documents, samples from using the Internet, computer video screen pictures or manuals covers illustrating programs you use)

Formal and technical documents as in grant or loan applications (include proposal cover sheet or award letter), technical manual

4. Demonstrate Your People Skills

Whether you work remotely or are client facing every day, you will at some point need to interact with other humans. Because of this, it’s necessary to show that you’re comfortable working with others in your career portfolio. Here are some simple ways to convey this:

People and leadership skills (projects or committees you share, projects you initiated, photos of you with important people, mentoring programs, proposals, documents or strategies related to negotiation)

Planning Samples (summary of steps, instruments used such as surveys or focus groups)

Problem solving illustrated with various artifacts. Use figures or pictures showing improvements in products, services, profits, safety, quality, or time. Include forms and other paper products used to solve problems

Employee training packets, interview sheets, motivational activities

5. Demonstrate Yours Tools Skills

When job-seekers are wondering what to include in a professional portfolio this is one thing that they often forget as well. Start with taking stock of what kind of tools you use in your current job. What tools will you need to use in your desired job?

Take some time to consider how this applies to you, then get to work on showing examples of your success with the tools specific to your area. Whether you use hammers or excel, gather reference materials that demonstrate your mastery of these tools and include them in your career portfolio! This can also be a great chance to be honest with yourself and identify a few things you might want to brush up on beforehand.

Any artifact which shows technical skills, equipment, or specialized procedures used in your work.

Paper documents or replicas of actual items including: forms, charts, print-outs (such as medical chart, financial statement or budgets, reports, emergency preparedness plan, marketing plan, customer satisfaction plan, inspection or evaluation sheet, financial or budget plans, spreadsheets, charts, official documents)

Performance records (keyboard timing scores, safety records, phone logs, complaint logs, pay stub with hours worked highlighted, any record showing volume, amount, total time, response time, turnaround time, dollars or sales figures, size of customer database, organization chart showing people supervised)

Technical directions, manuals, procedure sheets for specialized work, use of equipment, and detailed processes. This could include: sample pages from manuals, illustrations, technical drawings, blueprints or schematics, photos from the workplace, schematics or directions for tools or equipment, operation or procedure sheet

Photos, video, slide-show, or multi-media presentation showing process or equipment.

Actual items which can be handled in various ways: displayed in person one at a time or part of a display you set up

function load(e){var t=document.getElementsByTagName("head")[0],n=document.createElement("link");return n.type="text/css",n.rel="stylesheet",n.href=e,t.appendChild(n),n}load('//unpkg.com/[email protected]');

Get Your Career Portfolio In Front Of More Potential Employers.

Use our free tool to ensure your career portfolio shows up when employers Google your name.

Get started for free

6. The Issue With Career Portfolio Examples

A common request you get from people who want to know what to include in a portfolio is if they can see career portfolio examples. While we do think using a template as a high-level starting point can be helpful for some, we often find that many people fall into a trap once they get their hands on some career portfolio examples. The reason for this is they start to create and work within an existing framework in a way that loses their unique spin.

When you look at something through the eyes of someone else or from a one-size-fits-all viewpoint, this is one of the main disadvantages. When you are trying to create something that shows off what you have to offer as an individual, we always advocate that you do as much of it yourself as you can. If your professional portfolio ends up looking like everyone else’s you’re not going to stand out at all.

Another reason why we discourage you from using someone else’s example as a reference when developing your own professional portfolio is because there really isn’t a right or wrong way to do it. As long as you stick with the items and guidelines we’ve mentioned above, you will be completely fine.

What To Do Now

If you haven’t already, bookmark this page or copy and paste the items above for your reference. These items will guide your efforts when building or tweaking a career portfolio for years to come.

Also, try not to get overwhelmed when you’re starting to think about the first steps towards building an awesome career portfolio. It’s easy to put it off because you feel like a lot is riding on how good it makes you look to potential employers. Try to brush that aside and focus on the things that you do naturally that can help tell the story about who you are and what you do.

Don’t overlook smaller projects that you’ve worked on or events that you’ve participated in. Even you if you don’t end up sharing that information in your career portfolio – it’s better that you keep track of these kinds of mini-experiences so that you have the language and visuals to describe them later on if they do work well with other elements that you decide to include in your professional portfolio.

If you want to learn more about how to take something like your portfolio and tie it together with a personal brand that helps you accomplish your professional goals, sign up for a free BrandYourself account. Our software will guide you step by step through the process of developing an online reputation and personal brand with resources you have (like a career portfolio) and ones you should create.

The post 51 Items For Your Professional Career Portfolio + Examples appeared first on BrandYourself Blog | ORM And Personal Branding.

0 notes

Text

radEventListener: a Tale of Client-side Framework Performance

React is popular, popular enough that it receives its fair share of criticism. Yet, this criticism of React isn’t completely unwarranted: React and ReactDOM total about 120 KiB of minified JavaScript, which definitely contributes to slow startup time. When client-side rendering in React is relied upon entirely, it churns. Even if you render components on the server and hydrate them on the client, it still churns because component hydration is computationally expensive.

React certainly has its place when it comes to applications requiring complex state management, but in my professional experience, it doesn’t belong in most scenarios I see it used. When even a bit of React can be a problem on devices slow and fast alike, using it is an intentional choice that effectively excludes people with low-end hardware.

If it sounds like I have a grudge against React, then I must confess that I really like its componentization model. It makes organizing code easier. I think JSX is great. Server rendering is also cool—even if that’s just how we say “send HTML over the network” these days.

Still, even though I happily use React components on the server (or Preact, as is my preference), figuring out when it’s appropriate to use on the client is a bit challenging. What follows are my findings on React performance as I’ve tried to meet this challenge in a way that’s best for users.

Setting the scene

Lately, I’ve been chipping away at an RSS feed app side project called bylines.fyi. This app uses JavaScript on both the back and front end. I don’t think client-side frameworks are horrid things, but I’ve frequently observed two things about the client-side framework implementations I tend to run into in my day-to-day work and research:

Frameworks have the potential to inhibit a deeper understanding of the things they abstract, which is the web platform. Without knowing at least some of the lower level APIs that frameworks rely on, we can’t know what projects benefit from a framework, and which projects are better off without one.

Frameworks don’t always provide a clear path toward good user experiences.

You may be able to argue the validity of my first point, but the second point is becoming more difficult to refute. You might remember a little while ago when Tim Kadlec did some research on HTTPArchive about web framework performance, and came to the conclusion that React wasn’t exactly a stellar performer.

Still, I wanted to see if it was possible to use what I thought was best about React on the server while mitigating its ill effects on the client. To me, it makes sense to simultaneously want to use a framework to help to organize my code, but also restrict that framework’s negative impact on the user experience. That required a little experimentation to see what approach would be best for my app.

The experiment

I make sure to render every component I use on the server because I believe that the burden of providing markup should be assumed by the web app’s server, not the user’s device. However, I needed some JavaScript in my RSS feed app in order to get a toggleable mobile nav to work.

This scenario aptly describes what I refer to as simple state. In my experience, a prime example of simple state are linear A to B interactions. We toggle a thing on, and then we toggle it off. Stateful, but simple.

Unfortunately, I often see stateful React components used to manage simple state, which is a trade-off that’s problematic for performance. Though that may be a vague utterance for the moment, you’ll come to find out as you read on. That said, it’s important to emphasize that this is a trivial example, but it’s also a canary. Most developers—I hope—aren’t going to rely solely on React to drive such simple behavior for just one thing on their website. So it’s vital to understand that the results you’re going to see are intended to inform you on how you architect your applications, and how the effects of your framework choices could scale when it comes to runtime performance.

The conditions

My RSS feed app is still in development. It contains no third party code, which makes for easy testing in a quiet environment. The experiment I conducted compared the mobile nav toggle behavior across three implementations:

A stateful React component (React.Component) rendered on the server and hydrated on the client.

A stateful Preact component, also server-rendered and hydrated on the client.

A server-rendered stateless Preact component which was not hydrated. Instead, regular ol’ event listeners provide the mobile nav functionality on the client.

Each of these scenarios were measured across four distinct environments:

A Nokia 2 Android phone on Chrome 83.

A ASUS X550CC laptop from 2013 running Windows 10 on Chrome 83.

An old first generation iPhone SE on Safari 13.

A new second generation iPhone SE, also on Safari 13.

I believe this range of mobile hardware will be illustrative of performance across a broad spectrum of device capabilities, even if it’s slightly heavy on the Apple side.

What was measured

I wanted to measure four things for each implementation in each environment:

Startup time. For React and Preact, this included the time it took to load the framework code as well as hydrating the component on the client. For the event listener scenario, this included only the event listener code itself.

Hydration time. For the React and Preact scenarios, this is a subset of the startup time. Because of issues with remote debugging crashing in Safari on macOS, I couldn’t measure hydration time alone on iOS devices. Event listener implementations incurred zero hydration cost.

Mobile nav open time. This gives us insight into how much overhead frameworks introduce in their abstraction of event handlers, and how that compares to the frameworkless approach.

Mobile nav close time. As it turned out, this was quite a bit less than the cost of opening the menu. I ultimately decided not to include those numbers in this article.

It should be noted that measurements of these behaviors include scripting time only. Any layout, paint, and compositing costs would be in addition to and outside of these measurements. One should take care to remember that those activities compete for main thread time in tandem with scripts that trigger them.

The procedure

To test each of the three mobile nav implementations on each device, I followed this procedure:

I used remote debugging in Chrome on macOS for the Nokia 2. For iPhones, I used Safari’s equivalent of remote debugging.

I accessed the RSS feed app running on my local network on each device to the same page where the mobile nav toggling code could be run. Because of this, network performance was not a factor in my measurements.

Without CPU or network throttling applied, I began recording in the profiler, and reloaded the page.

After page load, I opened the mobile nav and then closed it.

I stopped the profiler, and recorded how much CPU time was involved in each of the four behaviors listed earlier.

I cleared the performance timeline. In Chrome, I also clicked the garbage collection button to free up any memory that may have been tied up by my app’s code from a previous session recording.

I repeated this procedure ten times for each scenario for each device. Ten iterations seemed to get just enough data to see a few outliers while getting a reasonably accurate picture, but I’ll let you decide as we go over the results. If you don’t want a play-by-play of my findings, you can view the results at this spreadsheet and draw your own conclusions, as well as the mobile nav code for each implementation.

The results

I initially wanted to present this information in a graph, but because of the complexity of what I was measuring, I wasn’t certain how to present the results without cluttering the visualization. Therefore, I’ll present the minimum, maximum, median, and average CPU times in a series of tables, all of which effectively illustrate the range of outcomes I encountered in each test.

Google Chrome on Nokia 2

The Nokia 2 is a low-cost Android device with a ARM Cortex-A7 processor. It is not a powerhouse, but rather a cheap and easily obtainable device. Android usage worldwide is currently around 40%, and though Android device specs vary greatly from one device to the next, low-end Android devices are not rare. This is a problem we must recognize as being one of both wealth and proximity to fast network infrastructure.

Let’s see what the numbers look like for startup cost.

Startup time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin137.2131.234.69Median147.7642.065.99Avg162.7343.166.81Max280.8162.0312.06

I believe it says something that it takes, on average, over 160 ms to parse and compile React, and hydrate one component. To remind you, startup cost in this case includes the time it takes for the browser to evaluate the scripts needed for the mobile nav to work. For React and Preact, it also includes hydration time, which in both cases can contribute to the uncanny valley effect we sometimes experience during startup.

Preact fares much better, taking around 73% less time than React, which makes sense considering how tiny Preact is at 10 KiB sans compression. Still, it’s important to note that the frame budget in Chrome is about 10 ms to avoid jank at 60 fps. Janky startup is as bad as janky anything else, and is a factor when calculating First Input Delay. All things considered, though, Preact performs relatively well.

As for the addEventListener implementation, it turns out that parse and compile time for a tiny script with no overhead is unsurprisingly very low. Even at the sampled maximum time of 12ms, you’re barely in the outer ring of the Janksburg Metropolitan Area. Now let’s have a look at hydration cost alone.

Hydration time

React ComponentPreact ComponentMin67.0419.17Median70.3326.91Avg74.8726.77Max117.8644.62

For React, this is still in the vicinity of Yikes Peak. Sure, a median hydration time of 70 ms for one component isn’t a big deal, but think about how hydration cost scales when you have a bunch of components on the same page. It’s no surprise that the React websites I test on this device feel more like endurance trials than user experiences.

Preact’s hydration times are quite a bit less, which makes sense because Preact’s documentation for its hydrate method states that it “skips most diffing while still attaching event listeners and setting up your component tree.” Hydration time for the addEventListener scenario isn’t reported, because hydration isn’t a thing outside of VDOM frameworks. Next, let’s take a peek at the time it takes to open the mobile nav.

Mobile nav open time

React ComponentPreact ComponentaddEventListener CodeMin30.8911.943.94Median43.6214.296.14Avg43.1614.666.12Max53.1920.468.60

I find these figures a bit surprising, because React commands almost seven times as much CPU time to execute an event listener callback than an event listener you could register yourself. This makes sense, as React’s state management logic is necessary overhead, but one has to wonder if it’s worth it for simplistic, linear interactions.

On the other hand, Preact manages to limit its overhead on event listeners to the point where it takes “only” twice as much CPU time to run an event listener callback.

CPU time involved in closing the mobile nav was quite a bit less at an average approximate time of 16.5 ms for React, with Preact and bare event listeners coming in at around 11 ms and 6 ms, respectively. I’d post the full table for the measurements on closing the mobile nav, but we have a lot left to sift through yet. Besides, you can check out those figures yourself in the spreadsheet I referred to earlier on.

A quick note on JavaScript samples

Before moving onto the iOS results, one potential sticking point I want to address is the impact of disabling JavaScript samples in Chrome DevTools when recording sessions on remote devices. After compiling my initial results, I wondered if the overhead of capturing entire call stacks was skewing my results, so I re-tested the React scenario samples disabled. As it turned out, this setting had no significant impact on the results.