Text

Post-Tonsillectomy Bleed: Recognizing, Managing, and Responding

Post-tonsillectomy bleeding is a significant concern in the realm of ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgery. With a prevalence of 4-8%, it stands as the most prevalent serious complication stemming from a seemingly routine procedure. In this blog post, we delve into the imperative knowledge surrounding post-tonsillectomy bleeds, red flags for detection, timely interventions, and subsequent management strategies.

Recognizing Red Flags

It is paramount for healthcare professionals to remain vigilant for certain indicators in patients who have recently undergone a tonsillectomy. These indicators, often referred to as red flags, include:

Bleeding from the Mouth or Nose: Any patient who reports bleeding from the mouth or nose shortly after a tonsillectomy warrants immediate attention and assessment.

Excessive Swallowing or Bloody Sputum in Young Children: Especially in young children who have recently undergone the procedure, the presence of excessive swallowing or bloody sputum requires careful evaluation.

Significance and Consequences

Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, though generally self-limiting, necessitates swift and adept management due to its potential to escalate. It is crucial to acknowledge that while these incidents are infrequent, instances of sudden severe hemorrhage can lead to dire outcomes, such as airway obstruction or hypovolemic shock.

When to Engage ENT Registrar

The involvement of the ENT registrar plays a pivotal role in the management of post-tonsillectomy bleeds. Immediate notification is warranted for patients experiencing active bleeding.

Assessment and Recognition

Bleeding can manifest within the first 24 hours post-surgery (reactive) or later (secondary). Secondary bleeds, often occurring between four to nine days post-operation, remain challenging to pinpoint. Possible causes include infection of sloughy material within the tonsillar fossae, potentially influenced by surgical technique.

Management: Immediate and Overnight

Immediate management mandates prioritization of the airway, along with measures to staunch bleeding and maintain hemodynamic stability. Steps include:

Elevation of the patient to encourage spitting of blood into a receptacle.

Access to suction equipment if required.

Calm reassurance to alleviate patient distress.

Insertion of large-bore intravenous access for fluid and blood tests.

Prompt collaboration with an anesthetist in cases of active bleeding.

Frequent hemodynamic monitoring.

NPO (nil per os) status to prevent oral intake.

Intravenous fluid resuscitation and analgesia.

Application of ice pack to the patient’s neck.

Consideration of intravenous tranexamic acid for its potential to mitigate bleeding.

Hydrogen peroxide gargles (3% solution diluted in three parts of water) for potential slow bleed control.

Progressive Management and Discharge

Continued bleeding or subsequent episodes warrant a call to the on-call ENT registrar and consideration of emergency theater intervention. For ongoing, stable bleeding, utilization of hydrogen peroxide gargles and ice packs can be employed for a short timeframe.

In the event of severe bleeding, when transfer to theater is pending, topical adrenaline application may temporarily alleviate hemorrhage. However, this approach should be pursued under senior guidance.

Post-tonsillectomy bleeding, while relatively infrequent, demands astute recognition, rapid response, and ongoing management. By adhering to stringent protocols and guidelines, healthcare professionals can mitigate the potential complications stemming from this common procedure. Awareness, vigilance, and effective communication among the medical team are vital to ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Title: Necrotizing Fasciitis: An In-Depth Exploration of Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Approaches

Introduction:

Necrotizing fasciitis, commonly referred to as the "flesh-eating disease," stands as a formidable entity within the realm of infectious diseases. This comprehensive discourse delves into the intricacies of its pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnostic nuances, and the evolving therapeutic strategies employed to combat this insidious affliction.

I. Pathogenesis: Deciphering the Intricacies

The origins of necrotizing fasciitis lay in the complex interplay of bacterial virulence factors and host immune response. The inciting events often involve polymicrobial or monomicrobial infiltration of subcutaneous tissues. Bacteria such as Streptococcus pyogenes secrete destructive enzymes, including hyaluronidases and proteases, which facilitate tissue degradation. The ischemic environment resulting from these processes allows anaerobic bacteria to thrive, further compounding the tissue devastation. Notably, the proclivity of Group A Streptococcus to exploit immunological naivety reinforces its virulence, rendering this organism a significant pathogenic protagonist.

II. Clinical Presentation: A Spectrum of Manifestations

The clinical portrait of necrotizing fasciitis is marked by a complex spectrum of manifestations. The initial mimicry of cellulitis gradually unfolds into a constellation of symptoms including fever, tachycardia, and disproportionate pain. Erythema rapidly escalates, often betraying the underlying seriousness of the condition. Notably, the presence of cutaneous anesthesia serves as a characteristic hallmark. Inspection of the skin reveals a transition from edema to a glossy, tense, and darkened appearance – an ominous harbinger of impending necrosis. This transformation is accompanied by the palpable wooden-hard consistency of subcutaneous tissue, often coupled with crepitus due to gas accumulation.

III. Diagnosis: A Precarious Balance

Diagnostic strategies for necrotizing fasciitis embrace a multi-faceted approach. Blood cultures are pivotal, as they often reveal the microbial culprit, with Streptococcus pyogenes occupying a predominant role. Elevated C-reactive protein levels and coagulation profiles serve as indices of the systemic inflammatory response. Radiological imaging, namely X-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), serve to visualize subcutaneous emphysema and ascertain the extent of tissue involvement. Biopsy augments diagnostic precision, enabling differentiation from conditions such as cellulitis.

Recent advancements have introduced point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) as a pivotal adjunct in the diagnostic armamentarium for necrotizing fasciitis. POCUS, often wielded by skilled practitioners at the bedside, engenders real-time visualization of tissue planes, facilitating early detection and accurate assessment of disease extent. This non-invasive modality offers remarkable precision, enabling differentiation between superficial cellulitis and the deeper involvement characteristic of necrotizing fasciitis. Moreover, POCUS aids in discerning subcutaneous emphysema, a cardinal feature of gas-forming infections. By appraising the subcutaneous tissue architecture, POCUS mitigates the diagnostic challenge posed by cutaneous anesthesia, substantiating the clinical diagnosis with objective imaging evidence. The integration of POCUS augments diagnostic confidence, expediting prompt therapeutic intervention and potentially mitigating disease progression. As POCUS continues to be harnessed in clinical practice, its utility as a veritable extension of the clinician's diagnostic acumen underscores the ongoing evolution of diagnostic paradigms in the realm of necrotizing fasciitis.

IV. Therapeutic Approaches: Navigating the Complex Landscape

The management of necrotizing fasciitis necessitates a multidisciplinary approach encompassing resuscitation, surgical intervention, and pharmacotherapy. Swift resuscitation addresses hemodynamic instability, aiming to restore tissue perfusion. Surgical debridement remains the cornerstone of intervention, seeking to halt disease progression and remove necrotic tissue. The pharmacological arsenal integrates clindamycin or lincomycin to counteract streptococcal exotoxins, supplemented by broad-spectrum antimicrobials targeting polymicrobial involvement. Meropenem emerges as a preferred choice due to its expansive coverage, while clindamycin synergizes by mitigating toxin production.

V. Current Research and Future Horizons: Hyperbaric Oxygen and Immunotherapy

The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in necrotizing fasciitis management remains subjects of ongoing investigation. Hyperbaric oxygen demonstrates potential benefits in select cases, particularly those involving anaerobic pathogens. IVIG, administered during the early phase, potentially mitigates the exuberant inflammatory response observed in necrotizing fasciitis associated with Group A Streptococcus.

Conclusion:

Necrotizing fasciitis, a complex amalgamation of microbial virulence and host immunology, continues to intrigue and challenge medical practitioners. This compendium illustrates its multifaceted dimensions, bridging the chasm between pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and evolving therapeutic modalities. As medical science evolves, the collective pursuit of unravelling this clinical enigma persists, exemplifying the symbiotic convergence of scientific advancement and clinical application. The saga of necrotizing fasciitis continues to underscore the indomitable spirit of human endeavor against the backdrop of microbial persistence.

0 notes

Text

Myocarditis in Emergency Practice

Myocarditis, an inflammatory condition affecting the heart's myocardial tissues, is a significant cause of sudden cardiac death and dilated cardiomyopathy. With diverse etiologies ranging from viral and immune-mediated causes to toxic exposures, diagnosing and managing myocarditis can be challenging. In this blog post, we will explore the important points regarding the etiology, pathophysiology, presentation, diagnostic testing, and treatment options for myocarditis, with a focus on the perspective of emergency physicians.

Myocarditis can be caused by infectious agents (bacterial, parasitic, viral), immune-mediated conditions, and toxic exposures. Viral causes include enteroviruses, influenza, hepatitis viruses, HIV, herpes viruses, and Parvo B-19. Immune-mediated causes include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), scleroderma, and giant cell types. Toxic agents such as doxorubicin, antiretroviral medications, clozapine, and cocaine can also trigger myocarditis.

Myocarditis follows a three-step process. In the acute phase, infectious, autoimmune, or toxic agents directly damage cardiac myocytes. Subsequent myocyte destruction triggers immune system activation and secondary inflammation. In the later stages, the immune system mistakenly attacks the myocytes themselves, leading to progressive myocardial damage.

Myocarditis presents with a wide range of symptoms, necessitating a high index of suspicion for timely diagnosis. Symptoms may include dyspnea, palpitations, orthopnea, and chest pain. Dyspnea is the most common presenting symptom, while chest pain can vary from pleuritic to anginal. Patients may exhibit symptoms of congestive heart failure, ranging from fatigue and peripheral edema to cardiovascular collapse. Skin manifestations can be present in cases triggered by medication exposure.

Diagnostic testing for myocarditis overlaps with other cardiopulmonary evaluations. Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, such as sinus tachycardia, ST-segment elevations, T-wave inversions, AV blocks, widened QRS durations, or prolonged QT intervals, may be observed. Troponin assays may be elevated, but their absence does not rule out myocarditis. Additional blood tests, including CBC, CRP, and ESR, are often abnormal but nonspecific. Imaging studies like chest radiography and echocardiography can provide valuable information.

TThe treatment of myocarditis primarily focuses on supportive care to prevent further damage to the heart. Stabilizing the patient's ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) is the priority. Supplemental oxygen and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation may be required for hypoxia or pulmonary edema. Heart failure therapy, including diuretics and nitroglycerin, can be administered if systemic perfusion allows. Cardiac dysrhythmias may necessitate treatment with antidysrhythmic medications. Antimicrobial therapy is required for cases associated with bacterial or parasitic infections. In severe cases, advanced interventions such as intra-aortic balloon pumps, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or ventricular assist devices (VADs) may be necessary.

Myocarditis presents a complex diagnostic and management challenge for emergency physicians. The diverse etiologies, varied clinical presentations, and overlapping diagnostic tests make timely diagnosis crucial. Supportive care, stabilization, and targeted interventions are key elements of treatment. While further research is needed to refine diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, understanding the etiology, pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment options can aid emergency physicians in effectively managing myocarditis cases.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#health & fitness#biology#emergency physician#foamed#myocarditis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unraveling the Enigma of Nitrous Oxide Induced Neurotoxicity: A Journey into the Complexities for Emergency Doctors

Welcome, esteemed emergency doctors, to a captivating exploration of Nitrous Oxide induced neurotoxicity—an enigmatic phenomenon that has captivated medical minds since its discovery in 1772. As a substance widely used both clinically and recreationally, Nitrous Oxide has recently raised concerns due to its potential neurotoxic effects. In this blog post, we embark on an intriguing journey into the depths of Nitrous Oxide induced neurotoxicity, emphasizing the vital role emergency doctors play in diagnosing and treating this condition.

The Hidden Dangers: Nitrous Oxide, often known as "laughing gas," has a long and storied history. Its euphoric effects have attracted both medical professionals and recreational users for centuries. However, recent studies have shed light on the potential hazards of its prolonged use. Neurotoxicity induced by Nitrous Oxide has been found to be dose-dependent, meaning that habitual and heavy users are at greater risk of experiencing severe neurological consequences. As emergency doctors, it is imperative to be aware of this association and to take a meticulous recreational drug history when confronted with patients presenting neurological symptoms.

The Elusive Presentations: Nitrous Oxide induced neurotoxicity can manifest in various forms, often puzzling clinicians with its diverse presentations. It may cause demyelination of the dorsal columns of the spinal cord or peripheral neuropathy—or even a combination of both. The onset of symptoms is typically subacute, occurring over weeks, but acute cases have also been reported. Patients may exhibit pyramidal weakness, sensory loss, sensory ataxia, and, in some instances, optic neuropathy leading to visual disturbances. These intricate presentations require astute clinical observation and a comprehensive understanding of the condition.

Unraveling the Mechanism: To comprehend the intricacies of Nitrous Oxide induced neurotoxicity, we must delve into its underlying pathophysiology. The usage of Nitrous Oxide interferes with the activation of vitamin B12, disrupting the process of myelination—the formation of the protective covering of nerves. This disruption ultimately leads to the demyelination of nerves and the subsequent neurological manifestations.

The Diagnostic Puzzle: When confronted with patients exhibiting neurotoxicity, differential diagnosis plays a vital role in elucidating the underlying cause. Deficiencies in essential nutrients such as vitamin B12, folate, copper, and zinc should be considered, along with inflammatory conditions like Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and neurosarcoidosis. Infection-related causes such as HIV and syphilis, as well as malignancies and vascular factors like spinal cord ischemia and vasculitis, should also be explored. Accurate diagnosis requires a meticulous evaluation of each patient's unique clinical picture.

Cracking the Code: Diagnostic tests form an integral part of the diagnostic process. While vitamin B12 levels may appear normal, additional assessments such as homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels, along with contrast-enhanced MRI scans, provide valuable insights. However, given the urgency of treatment, it is crucial to initiate therapy based on clinical suspicion, even before test results are available. Swift action is of paramount importance in ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Navigating the Treatment Maze: The cornerstone of treating Nitrous Oxide induced neurotoxicity lies in the restoration of vitamin B12 function. Intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 (1mg OD) and oral supplementation of folic acid (5mg OD) form the basis of the treatment approach. Collaborating with medical teams to discuss potential admission for specialized management is advisable, ensuring a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Enhancing Care for Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: New NICE Guidelines

Introduction: Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a critical condition characterized by bleeding in the space between the brain and the thin tissues covering it. While advancements have been made in improving outcomes for SAH patients, the risk of death remains high, and survivors often face severe disabilities. Recognizing the need for more effective diagnosis and management, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK has recently issued new guidelines. These guidelines aim to expedite diagnosis, enhance treatment decisions, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Key Recommendations:

• Urgent Review by Senior Clinical Decision-Maker: To ensure swift and accurate assessment, individuals with suspected SAH in acute hospital settings should be promptly reviewed by a senior clinical decision-maker, such as a doctor at the ST4 level in the UK. Their expertise will aid in expediting the diagnostic process and making timely treatment decisions.

• Urgent Non-Contrast CT Head Scan: For all patients with suspected SAH, it is recommended to order an urgent non-contrast computed tomography (CT) head scan as soon as possible, preferably within 6 hours of symptom onset. This scan plays a crucial role in accurately diagnosing SAH, facilitating early intervention.

• Lumbar Puncture Consideration: In cases where the CT head scan performed more than 6 hours after symptom onset is inconclusive or negative, a lumbar puncture (LP) should be considered. However, it is important to wait at least 12 hours after symptom onset before conducting an LP, if deemed necessary. This cautious approach helps avoid potential complications.

• Collaboration with Specialist Neurosurgical Centers: Upon confirming the diagnosis of SAH, it is advised to urgently discuss the patient's case with a specialist neurosurgical center. This step ensures timely transfer of care to a facility with the expertise and resources to provide optimal management and treatment plans for SAH patients.

• Angiography for Identifying Causal Pathology: Angiography, a diagnostic imaging technique, is recommended to identify the underlying pathology causing SAH. It aids in understanding the anatomy and assists in planning the most suitable approach to securing the aneurysm related to the hemorrhage. This information is vital for determining the best treatment strategy.

• Enteral Nimodipine and Intravenous Administration: For all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SAH, enteral nimodipine is recommended unless it is contraindicated. This medication helps prevent complications related to blood vessel constriction. However, in specific cases where enteral treatment is unsuitable, intravenous nimodipine should only be administered within specialist settings.

The new NICE guidelines for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) offer valuable recommendations to improve diagnosis and enhance the effectiveness of treatment. By ensuring urgent reviews by senior clinical decision-makers, expediting non-contrast CT head scans, considering lumbar puncture judiciously, collaborating with specialist neurosurgical centers, utilizing angiography, and administering nimodipine appropriately, healthcare professionals can enhance patient care and improve outcomes for individuals affected by SAH. These evidence-based guidelines underscore the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and the involvement of patients and their families in deciding the most suitable treatment plan. By implementing these recommendations, healthcare providers can strive towards better management and improved quality of life for SAH patients.

0 notes

Text

Lateral Canthotomy: A Critical Procedure for Acute Visual Loss

Lateral canthotomy is a surgical procedure performed to alleviate acute, potentially irreversible visual loss secondary to increased intraocular pressure from orbital compartment syndrome. This condition can arise from a variety of causes, including traumatic injury, infection, or bleeding, and requires prompt intervention to prevent permanent vision loss. In this article, we will explore the indications, technique, risks, and benefits of lateral canthotomy in the emergent setting.

Indications for Lateral Canthotomy

Orbital compartment syndrome is a potentially devastating condition that arises from increased intraocular pressure in the eye, leading to compromised blood flow to the optic nerve and retina. The resulting ischemia can cause irreversible vision loss if left untreated. Lateral canthotomy is a critical procedure that can decompress the orbit and alleviate the increased intraocular pressure, restoring blood flow and preventing further damage to the optic nerve and retina.

The signs and symptoms of orbital compartment syndrome can vary but may include severe eye pain, decreased vision, proptosis (bulging eye), chemosis (swelling of the conjunctiva), and resistance to eye movement. These findings are concerning and should prompt immediate evaluation by a trained medical professional.

Technique of Lateral Canthotomy

Lateral canthotomy is a relatively simple procedure that can be performed in the emergent setting by trained medical professionals, including emergency physicians and ophthalmologists. Proper technique is crucial to maximize safety and minimize risks, including bleeding, infection, and injury to the eye or adjacent structures.

The procedure involves a series of steps, beginning with proper sedation and pain management to ensure patient comfort during the operation. Sterile technique should be followed, including cleaning the skin with chlorhexidine and sterile draping of the surgical field.

Local anesthetic is infiltrated from the lateral canthus to the orbital rim to provide proper nerve blockage and minimize patient discomfort. Eye irrigation with saline solution is carried out to clear any debris or blood, while a straight mosquito hemostat is placed along the lateral canthus and applied for one minute to minimize bleeding. This provides a clear surgical field and reduces the risk of hemorrhage.

Once the hemostat is removed, a straight iris scissors is used to incise all layers of tissue along the same path, creating a flap of tissue that is lifted to expose the lateral canthus. Using forceps, the lower eyelid is grasped and retracted to reveal the lateral canthal tendon, located inferior and posterior to the lateral canthal fold. The tendon is then severed completely through the middle of the lateral canthal ligament with the iris scissors, effectively decompressing the orbital compartment and reducing intraocular pressure.

Risks and Benefits of Lateral Canthotomy

While lateral canthotomy is generally considered safe, there are potential risks and complications to consider. These may include bleeding, infection, injury to the eye or adjacent structures, and adverse reactions to anesthesia or pain medication. Careful monitoring of the patient's post-procedural course is essential, with close observation for any signs of bleeding, infection, or ocular complications. Follow-up care, including ophthalmologic evaluation, is also important to ensure adequate healing and restoration of vision.

The benefits of lateral canthotomy, however, far outweigh the risks in the emergent setting. This procedure is critical for the prevention of irreversible vision loss, and prompt intervention can lead to excellent outcomes and preservation of visual function.

Conclusion

Lateral canthotomy is a critical procedure that can alleviate acute visual loss and prevent permanent damage to the optic nerve and retina. As an emergent procedure, it requires careful consideration of the patient's medical history, co-morbidities, and potential risks and benefits.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#health & fitness#biology#emergency physician#foamed#fitblr#lateral canthotomy#acute vision loss#intraocular pressure#orbital compartment syndrome#ophthalmology#surgical procedure#eye surgery#eye trauma#eye injury#eye emergency#vision loss

0 notes

Text

Temperature Monitoring and Rewarming Techniques for Hypothermic Patients

Hypothermia is a condition where body temperature falls below normal. It can be a life-threatening condition that needs immediate medical attention. Medical professionals must know the proper techniques for rewarming hypothermic patients.

Temperature Monitoring: Core temperature monitoring is crucial in assessing the efficacy of rewarming measures. Continuous or serial rectal or oesophageal thermometer can be used to accomplish this. However, rectal thermometer may lag behind core temperature increases due to impaction into frozen faeces, and the oesophageal thermometer may give false elevated readings when heated, humidified oxygen is being administered.

Fluid Resuscitation: Hypothermic patients are generally dehydrated and fluid depleted, so they should be given a fluid challenge of warmed 0.9% saline or preferably Dextrose-Saline. Hartmann's solution should be avoided. Patients must be carefully monitored for signs of fluid overload.

Passive Rewarming: Patients suffering from mild hypothermia that can still generate heat by shivering can benefit from this principle. This technique allows the patient's own thermogenic mechanisms to rewarm them. They should be removed from the cold environment, and their wet or cold clothes should be removed. They can then be covered with a blanket or sleeping bag and have their head covered to reduce heat loss.

Active External Rewarming: This method involves adding heat to the patient from an external source. It is the treatment of choice in mild-moderate hypothermia patients whose own thermoregulatory mechanisms are impaired. The most widely used means of active external rewarming in current use is forced air systems, which allow for patient monitoring and limit afterdrop.

Active Core Rewarming: Patients with moderate to severe hypothermia will require active core rewarming, which comprises a variety of techniques. The simplest example of active core rewarming is the use of warmed intravenous fluids and warmed, humidified oxygen. More invasive methods include cavity lavage using warm fluids.

Extracorporeal Blood Rewarming: This is used to aggressively rewarm blood in severely hypothermic patients who have been refractory to all other methods. The biggest advantage of this method is the speed at which the patient can be rewarmed by directly warming their blood. Extracorporeal rewarming should be considered for patients without perfusion who have no documented contraindications to resuscitation, patients with severe hypothermia, and those with completely frozen extremities.

Hypothermic Cardiac Arrest: Establishing and treating cardiac arrest in the severely hypothermic patient can be challenging. The European Resuscitation Council 2010 guidelines recommend up to three defibrillation attempts, to withhold adrenaline until the core temperature exceeds 30 C, and to double the dose frequency until the temperature is above 35 C. It is unclear as to the rate and force needed for cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the severely hypothermic patient.

In summary, medical professionals must know the proper techniques for rewarming hypothermic patients. Different methods may be employed depending on the severity of hypothermia. Temperature monitoring is crucial to assess the efficacy of rewarming measures. Proper fluid resuscitation and rewarming methods are essential in managing hypothermic patients.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hip joint dislocations frequently present in emergency departments, and medical professionals are trained in various techniques to manage this condition. The Allis manoeuvre, which involves a person standing on the patient's bed, is commonly taught for relocating a hip joint. However, healthcare providers may consider this technique precarious.

An alternative technique, the Captain Morgan technique, can be employed to safely and effectively relocate a dislocated hip joint. This technique involves applying three forces of axial traction to the femur. The following instructions describe the steps to perform the procedure in a clear and concise manner:

Step 1: Patient Positioning

Position the patient with 90 degrees of hip and knee flexion.

Step 2: Captain Morgan Stance

Assume the Captain Morgan stance by stepping one foot up onto the gurney, ideally resting on a hard surface such as a backboard to provide a firm base to push off of.

Step 3: Knee Positioning

Position the knee behind the patient's knee.

Step 4: Hand Placement

Place one hand (Hand A) under the patient's knee and the other (Hand B) over the patient's ankle.

Step 5: Femur Lifting

Use Hand A to lift up on the patient's femur.

Step 6: Ankle Plantar-flexion

Plantar-flex your ankle to enable the propped knee to lift up on the patient's femur.

Step 7: Tibia/Fibula Leverage-Down

Leverage down gently against the patient's tibia/fibula using Hand B.

The Captain Morgan technique is a reliable and effective alternative to the Allis manoeuvre for relocating a hip joint. While the procedure may seem unconventional, it has proven to be a safe and effective approach.

0 notes

Text

Slipped rib syndrome, also referred to as Cyriax syndrome, is a rare medical condition that is characterized by discomfort in the upper abdomen or lower chest area. The source of this discomfort can be attributed to excessive movement of the cartilage in the ribcage, and in this article, we will explore a number of complex factors related to this ailment, including its epidemiology, clinical presentation, pathology, radiographic features, treatment, and prognosis.

It is worth noting that slipped rib syndrome is not limited to a specific age group, but it is more commonly observed in individuals in their middle years. While this condition can cause recurring pain in adolescents, it is less common in young children due to the flexibility of their ribcages. Furthermore, there is no clear gender preference for slipped rib syndrome.

In terms of its clinical presentation, slipped rib syndrome can manifest as intermittent sharp stabbing pain in the back or upper abdomen, accompanied by a dull aching sensation. Patients may experience unusual sensations such as clicking or popping in the lower ribs, and certain movements like twisting, turning in bed, lifting, and bending can exacerbate symptoms. When examining the affected area, a tender spot on the costal margin is typically detected, and this is associated with the specific pain that patients experience. Furthermore, the hooking manoeuvre, which involves placing the fingers in the subcostal region and pulling in an anterior cranial direction, can also reproduce this pain. While most cases of slipped rib syndrome occur unilaterally, bilateral cases can occur.

The pathology of slipped rib syndrome is not completely understood, but it is believed that trauma, injury, or surgery may be contributing factors, although cases without these issues have been reported. The condition is thought to result from hypermobility of the rib cartilage or ligaments, with ribs 8, 9, and 10 being particularly affected. This movement can irritate the nerves and potentially strain intercostal muscles in the area, leading to inflammation and pain.

While the diagnosis of slipped rib syndrome is often made based on clinical examination, imaging may be necessary to rule out intrathoracic or intra-abdominal pathologies. Dynamic ultrasound may be used to demonstrate slipping of the costochondral area of the rib.

Treatment for slipped rib syndrome generally involves pain relief and modifying activity, and local anaesthetic intercostal nerve block injections or corticosteroids can be helpful in alleviating discomfort. In cases where pain is persistent or severe, surgical interventions such as costal cartilage excision or minimally invasive repair may be required, although the former may not necessarily prevent the recurrence of late pain. While slipped rib syndrome can be debilitating due to the severity of pain, it does not typically result in any serious complications.

It is important to keep in mind that differential diagnoses such as cholecystitis, oesophagitis, gastric ulcers, stress fractures, muscle tears, pleuritic chest pain, costochondritis, Tietze syndrome, and bone metastases should be considered.

It is worth noting that slipped rib syndrome is a frequently underdiagnosed condition. By being aware of this ailment, it is possible to prevent a delay in diagnosis and avoid unnecessary

laboratory and radiological investigations.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#health & fitness#biology#emergency physician#slippe rib syndrome

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

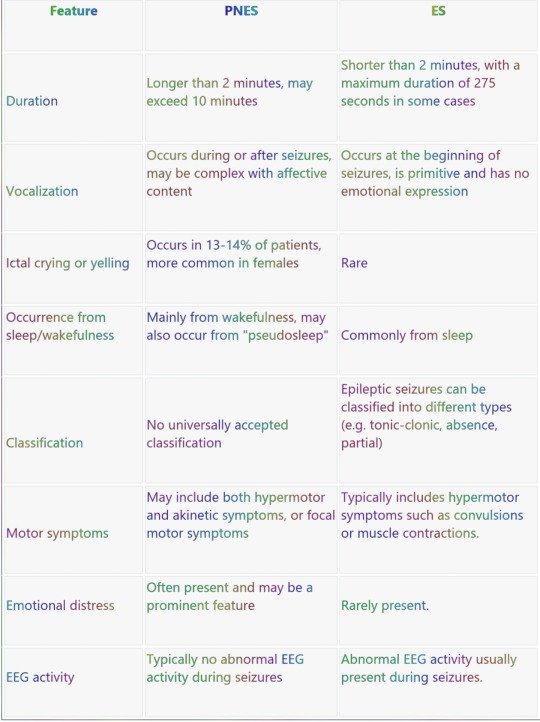

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) can be clinically challenging to diagnose, as they often mimic different types of epilepsy seizures (ES). A recent study has highlighted the extent to which features of PNES semiology may distinguish PNES patients from those with epilepsy. It is important to note that a single sign is unreliable as a diagnostic discriminator, and even informed specialists often contextualize multiple signs to hypothesize seizure etiology. Clusters of semiological elements may differentiate PNES more clearly from ES.

The following table mentions some of the major discriminating factors between the two:

It's worth noting that these differences are not absolute, and there may be overlap between PNES and ES.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#health & fitness#biology#epilepsy#pnes#ES#emergency physician#FoaMed

1 note

·

View note

Text

ST elevation in aVR with co-existent multi-lead ST depression is a pattern seen on an electrocardiogram (ECG) that indicates subendocardial ischemia, which is a lack of blood flow to the innermost layer of the heart muscle. This is caused by an imbalance between the oxygen supply and demand of the heart, which can have several clinical causes.

The most common causes of this ECG pattern include stenosis, or narrowing, of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) or the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), as well as severe triple vessel disease. In rare cases, hypoxia or hypotension can also cause this pattern, such as following cardiac arrest.

Additionally, this pattern can also be seen in the context of anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) due to LAD occlusion proximal to the first septal branch, causing infarction of the basal septum. Such cases will have associated ST elevation in anteroseptal leads.

The mechanism of ST elevation in aVR is multifaceted, lead aVR is electrically opposite to the left-sided leads I, II, aVL and V4-6, In subendocardial ischaemia, ST elevation in aVR is simply a reciprocal change to ST depression in these leads.

It's also important to note that while this ECG pattern can be indicative of acute LMCA occlusion, more recent research has shown that this is not always the case. Studies have shown that LMCA "occlusion" is actually a misnomer, and that this ECG pattern is more consistent with left main coronary artery subocclusion or complete occlusion with well-developed collateral circulation.

In conclusion, ST elevation in aVR with co-existent multi-lead ST depression is a pattern seen on an ECG that indicates subendocardial ischemia. The most common causes of this pattern include stenosis of the LMCA or the proximal LAD, as well as severe triple vessel disease. It is important for physicians to be aware of this pattern and its potential causes, in order to provide prompt and accurate diagnosis and treatment for patients.

0 notes

Text

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, leading to difficulty breathing. It is a common condition that affects people of all ages and can range from mild to severe. In severe cases, asthma can be life-threatening and require emergency treatment.

In the emergency department, the main goal of treatment is to relieve symptoms and restore normal breathing as quickly as possible. Established treatments for asthma in the emergency department include oxygen therapy, beta-agonists, anticholinergics, corticosteroids, and aminophylline.

Oxygen therapy is an important part of treatment for severe asthma. It is typically given through a face mask and is titrated to maintain a oxygen saturation (SpO2) of at least 92%. Beta-agonists, such as salbutamol, can be given through nebulization, a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), or intravenously (IV). Anticholinergics, such as ipratropium bromide, can be given through nebulization and may be administered every 2-6 hours. Corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone or prednisone, can help reduce inflammation in the airways and may be given every 6 hours or at a dosage of 0.5mg/kg/day. Aminophylline is a bronchodilator that can be given as a loading dose of 6mg/kg followed by a continuous infusion of 0.5mg/kg/hr. It is important to monitor aminophylline levels and aim for a range of 30-80micromol/L.

There are also non-established treatments for asthma in the emergency department that may be used in certain cases. These include adrenaline, magnesium sulfate, heliox, ketamine, inhalational agents, leukotriene antagonists, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Adrenaline can be given through nebulization, subcutaneous injection, or IV infusion. Magnesium sulfate can be given as a 20-minute infusion of 5-10mmol, with higher dosages of up to 80mmol used in some cases. Heliox is a mixture of helium and oxygen that can reduce turbulent air flow and may be used in cases of severe asthma. Ketamine is an anesthetic that can be given as a continuous infusion at a dosage of 0.5-2mg/kg/hr. Inhalational agents, such as sevoflurane, can be used to help manage asthma, but require the use of an anaesthetic machine or a custom fitted ventilator. Leukotriene antagonists are a class of medications that may provide some benefit in chronic asthma. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) involves the instillation of saline into the airways to clear mucous plugging, although it may transiently worsen bronchospasm.

In conclusion, the management of asthma in the emergency department involves the use of established treatments such as oxygen therapy, beta-agonists, anticholinergics, corticosteroids, and aminophylline, as well as non-established treatments that may be used in certain cases. The main goal is to relieve symptoms and restore normal breathing as quickly as possible.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Takotsubu cardiomyopathy, also known as stress cardiomyopathy, apical ballooning syndrome, or broken heart syndrome, is a transient wall motion abnormality of the left ventricular apex associated with severe emotional or physical stress that usually resolves completely. It produces ischemic chest pain, ECG changes, and potentially elevated cardiac enzymes in patients with normal coronary arteries on angiography. The presentation often mimics a STEMI (ST segment elevation myocardial infarction) and angiography is required to definitively differentiate the two conditions.

According to the Mayo Clinic, diagnostic criteria for Takotsubu cardiomyopathy include: transient dyskinesis of the LV apical and/or midsegments, regional wall motion abnormalities beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution, absence of coronary artery stenosis greater than 50% of the culprit lesion, new ECG changes (ST elevation or T wave inversion) or moderate troponin rise, and absence of phaeochromocytoma and myocarditis.

Takotsubu cardiomyopathy is most commonly seen in post-menopausal women, with 90% of cases occurring in this population. These cases are often associated with sudden emotional stress. Cases in men are more likely to be associated with physical stress.

One of the key challenges in the management of Takotsubu cardiomyopathy is the difficulty in distinguishing it from STEMI in the emergency department. There are no ECG criteria that can safely be used to differentiate between the two conditions. If there is any doubt, it is recommended to activate the local STEMI protocol. While Takotsubu cardiomyopathy has a better prognosis than STEMIs with a similar ECG, it is certainly not a benign condition. Treatment is largely supportive, with LV function usually returning to normal within 21 days of onset. Anticoagulation should be initiated in patients with large areas of cardiac hypokinesis, as they are at high risk for cerebrovascular thromboembolic events.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#health & fitness#biology#cardiology#echo#ecg#emergency physician#emergency department

0 notes

Text

Arrhythmic Storm, or Refractory Ventricular Tachycardia/Fibrillation (VT/VF), is a life-threatening condition that can be extremely difficult to manage. It is defined as having three or more sustained episodes of VT, VF, or appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks within a 24-hour period.

The pathophysiology of VT/VF storm is complex and can be influenced by sympathetic drive in many cases. This is why it is often recommended to use beta-blockers and avoid adrenaline in the management of this condition. However, VT/VF storm can also result from different underlying pathologies, such as Brugada syndrome or early repolarisation, which may require different approaches to treatment.

When managing VT/VF storm, it is important to first perform usual resuscitation measures and attend to the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation). It is also important to adhere to International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) guidelines and seek and treat any underlying causes or complications. Effective CPR should be continued, using devices like the LUCAS CPR system and the ResQPod impedance threshold device to help reduce fatigue in rescuers.

If VT/VF persists despite several shocks, "double down" defibrillation can be considered. This involves applying two sets of defibrillator pads to the patient, one in the traditional sternum/apex configuration and the other in the AP configuration, and coordinating the simultaneous firing of both defibrillators. Other options for managing refractory VT/VF include the use of drugs like amiodarone, magnesium, and lignocaine, and techniques to attenuate sympathetic drive such as esmolol and ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion blockade.

For VT/VF storm in the setting of Brugada syndrome, isoprenaline infusion has been used successfully. Quinidine may also be considered. It is important to note that other anti-arrhythmics, such as beta-blockers, amiodarone, lignocaine, and magnesium, are not usually effective in this context. In cases where VT/VF storm does not respond to other measures, extracorporeal support (such as ECMO) and radiofrequency catheter ablation may be considered, particularly if electrophysiological studies have localised a region giving rise to VF-inducing PVCs.

In summary, VT/VF storm is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition that requires prompt and effective management. It is important to attend to the ABCs, follow ILCOR guidelines, and seek and treat underlying causes and complications. Multiple treatment options, including defibrillation, drugs, and techniques to attenuate sympathetic drive, are available and should be considered in the management of VT/VF storm. In certain cases, extracorporeal support and radiofrequency catheter ablation may also be necessary.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare, but potentially life-threatening condition that can occur as a side effect of certain medications known as neuroleptics or antipsychotics. These medications are often used to treat psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression, but they can also be used for other conditions such as nausea and vomiting, or as a sedative.

Symptoms of NMS may include fever, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and abnormal movements. These symptoms can progress quickly and may lead to organ failure and death if not treated promptly.

Management of NMS in the emergency department (ED) is crucial to prevent complications and ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. The first step in the management of NMS is to immediately stop the neuroleptic medication that may be causing the syndrome. The patient should also be closely monitored for changes in vital signs, mental status, and any other symptoms that may occur.

Intravenous fluids, electrolytes, and medications such as dantrolene and bromocriptine may be used to help control the symptoms of NMS. Dantrolene helps to relax the muscles and reduce muscle rigidity, while bromocriptine can help to reduce fever and improve mental status. In severe cases, mechanical ventilation may be necessary to assist with breathing.

It is important to closely monitor the patient for any changes in their condition and to promptly address any complications that may arise. Close communication with the patient's healthcare team, including their primary care provider and a psychiatrist, is also essential in the management of NMS.

In addition to the steps mentioned above, it is important for the healthcare team to be aware of any potential risk factors for NMS. These may include:

• Use of high doses of neuroleptic medications

• Rapid escalation of neuroleptic dosage

• Use of multiple neuroleptic medications

• Previous history of NMS

• Older age

• Alcohol or substance abuse

• Dehydration

• Electrolyte imbalances

It is also important for the healthcare team to be aware of the potential for NMS to occur in patients who are taking other medications that may increase the risk of NMS. These may include:

• Lithium

• Tricyclic antidepressants

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

In order to prevent NMS, it is important to carefully monitor patients who are taking neuroleptic medications and to use the lowest effective dosage. Regular monitoring of vital signs and mental status, as well as monitoring for any adverse reactions or side effects, is also important.

If NMS is suspected, it is important to immediately stop the neuroleptic medication and to seek medical attention. Early recognition and treatment of NMS can significantly improve the outcome for the patient.

There are several medications that may be used in the treatment of NMS. These include:

• Dantrolene: This medication helps to relax the muscles and reduce muscle rigidity, which is a common symptom of NMS. It is typically given intravenously, and may be used in combination with other medications. The recommended starting dose of dantrolene is 2.5 mg/kg intravenously, followed by 1.25-2.5 mg/kg every six hours as needed. The maximum daily dose is typically 20-30 mg/kg.

• Bromocriptine: This medication can help to reduce fever and improve mental status in patients with NMS. It is typically given orally or intravenously. The usual starting dose of bromocriptine is 2.5-5 mg orally or intravenously, followed by 1.25-5 mg every six hours as needed. The maximum daily dose is typically 20-30 mg.

• Levodopa: This medication is a precursor to dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is involved in the regulation of muscle movement and other functions. It may be used in combination with a decarboxylase inhibitor to help reduce muscle rigidity and other symptoms of NMS. The usual starting dose of levodopa is 250-500 mg orally, followed by 250-500 mg every four hours as needed. The maximum daily dose is typically 3-4 grams.

• Benzodiazepines: These medications are commonly used to treat anxiety and sleep disorders, but they can also be used to help control muscle rigidity and other symptoms of NMS. Common benzodiazepines include lorazepam and diazepam. The usual starting dose of lorazepam is 2-4 mg orally or intravenously, followed by 1-2 mg every six hours as needed. The maximum daily dose is typically 10-20 mg. The usual starting dose of diazepam is 2-10 mg orally or intravenously, followed by 2-10 mg every six hours as needed. The maximum daily dose is typically 40 mg.

It is important to note that the specific treatment plan for NMS will depend on the severity of the condition and the individual needs of the patient. Close monitoring and communication with the healthcare team is essential to ensure that the appropriate treatment is provided.

In conclusion, the management of NMS in the ED is crucial to prevent complications and ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. Prompt recognition and treatment of NMS is essential, and close communication with the patient's healthcare team is key to ensuring a successful outcome. Careful monitoring of patients taking neuroleptic medications and the use of the lowest effective dosage can help to prevent the development of NMS. If NMS is suspected, it is important to immediately stop the neuroleptic medication and seek medical attention. Early recognition and treatment of NMS can significantly improve the outcome for the patient.

#emergency medicine#acute care#emergency#biology#health & fitness#fiction#psychology#NMS#neuroleptic malignant syndrome

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tranquilizers, also known as anxiolytics or psychotropic drugs, are medications that are used to treat anxiety, insomnia, and other mental health disorders. In the emergency department (ED), tranquilizers are often used to manage agitated or distressed patients, or to sedate patients before procedures.

There are several different types of tranquilizers that are commonly used in the ED, each with its own unique set of characteristics and potential side effects.

• Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are a class of tranquilizers that are widely used in the ED due to their fast-acting sedative effects and low risk of overdose. They work by enhancing the activity of a neurotransmitter called GABA, which slows down the activity of the brain and central nervous system.

Examples of benzodiazepines include lorazepam (Ativan), diazepam (Valium), and midazolam (Versed). These medications are typically given intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM) in the ED and can be used to treat anxiety, insomnia, and alcohol withdrawal.

• Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics or major tranquilizers, are a class of medications that are used to treat psychosis, schizophrenia, and other mental health disorders. They work by blocking the action of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that is involved in the regulation of mood and behavior.

Examples of antipsychotics include haloperidol (Haldol), olanzapine (Zyprexa), and quetiapine (Seroquel). These medications are typically given orally or by injection in the ED and can be used to treat agitation, psychosis, and delirium.

• Beta blockers

Beta blockers are a class of medications that are commonly used to treat hypertension, angina, and other cardiovascular conditions. They work by blocking the action of the hormone adrenaline, which can help to reduce anxiety and heart rate.

Examples of beta blockers include propranolol (Inderal) and metoprolol (Lopressor). These medications are typically given orally or by injection in the ED and can be used to treat anxiety, hypertension, and tachycardia.

• Sedative-hypnotics

Sedative-hypnotics are a class of medications that are used to induce sleep or sedation. They work by slowing down the activity of the brain and central nervous system.

Examples of sedative-hypnotics include lorazepam (Ativan), zolpidem (Ambien), and eszopiclone (Lunesta). These medications are typically given orally or intravenously in the ED and can be used to treat insomnia and anxiety.

• Alpha-2 agonists

Alpha-2 agonists are a class of medications that are used to sedate patients and reduce anxiety. They work by activating alpha-2 receptors in the brain, which can help to reduce the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and lower blood pressure.

Examples of alpha-2 agonists include clonidine (Catapres) and dexmedetomidine (Precedex). These medications are typically given intravenously or intramuscularly in the ED and can be used to treat agitation and hypertension.

• Barbiturates

Barbiturates are a class of medications that are used to induce sleep or sedation. They work by enhancing the activity of GABA, a neurotransmitter that slows down the activity of the brain and central nervous system.

Examples of barbiturates include pentobarbital (Nembutal) and secobarbital (Seconal). These medications are typically given intravenously or intramuscularly in the ED and can be used to treat severe anxiety or to induce coma in cases of life-threatening conditions such as intracranial pressure or status epilepticus.

It's important to note that all tranquilizers have the potential for side effects and should be used with caution. Common side effects of tranquilizers include drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, and constipation. In rare cases, tranquilizers can also cause more serious side effects such as respiratory depression, hypotension, and paradoxical reactions (e.g., agitation or excitement instead of sedation).

In conclusion, tranquilizers are a valuable tool in the management of agitated or distressed patients in the ED. However, it's important for healthcare providers to carefully consider the risks and benefits of these medications and to use them appropriately to minimize the risk of side effects.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hypernatraemia is a condition in which the concentration of sodium in the blood is elevated above the normal range. It can occur as a result of a number of different underlying conditions, such as diabetes insipidus, excess intake of sodium, or kidney disease. It is important to diagnose and treat hypernatraemia promptly, as it can lead to serious complications if left untreated.

The approach to managing hypernatraemia involves several steps, including calculating the free water deficit, determining a suitable serum sodium correction rate, estimating ongoing free water losses, and designing a fluid repletion programme. It is also important to monitor the patient closely during treatment to ensure that the desired effects are being achieved.

Calculating the free water deficit is an important step in the management of hypernatraemia. The free water deficit formula is used to determine the amount of fluid needed to correct the condition. The formula takes into account the patient's total body water and the concentration of sodium in the plasma.

Determining a suitable serum sodium correction rate is another important aspect of managing hypernatraemia. In patients with severe symptoms, the serum sodium concentration should be lowered by 2 mmol/L/hour in the first 2-3 hours, followed by a correction rate of 0.5 mmol/L/hour thereafter. The aim is to lower the serum sodium level by 10 mmol/L/day in these patients, if possible. However, the rate of correction should be adjusted based on the patient's clinical condition and the presence of any underlying conditions.

Estimating ongoing free water losses is also important in the management of hypernatraemia. This can be done using the electrolyte-free water excretion formula, which takes into account the urine flow rate, the concentration of sodium and potassium in the urine, and the concentration of sodium in the plasma. If urine output or the electrolyte content of the urine changes, then the electrolyte-free water excretion should be recalculated.

Designing a fluid repletion programme is another important aspect of managing hypernatraemia. This involves determining the type and amount of fluids that should be administered to the patient in order to correct the condition. In most cases, water administration via the oral route is preferred. If this is not possible, intravenous administration may be necessary. It is important to choose the appropriate type of fluids and to monitor the patient for the development of any complications, such as hyperglycaemia.

Monitoring the patient closely during treatment is also important in the management of hypernatraemia. This involves regularly checking the patient's vital signs and monitoring their clinical condition. It is also important to monitor the patient's electrolyte levels and urine output in order to ensure that the treatment is effective.

In cases of hypernatraemia due to diabetes insipidus, treatment may involve the use of medications such as desmopressin, which can help to stop ongoing losses of electrolyte-free water. In cases of accidental or iatrogenic excess intake of sodium, treatment may involve restricting sodium intake and increasing fluid intake. In cases of renal replacement therapy, treatment may involve the use of dialysis or other forms of renal replacement therapy.

Overall, the management of hypernatraemia requires a careful and individualised approach that takes into account the patient's underlying condition and clinical status. It is important to work closely with the healthcare team in order to ensure the most effective and appropriate treatment for the patient.

0 notes