Text

What is Seasteading? A discussion on the neoliberal fantasy of homesteading on the sea - disaster issue Alessandro Bava, architect and Renaissance man Martti Kalliala, and artist Daniel Keller discuss #seasteading and Tech-Secessionism - Dismagazine

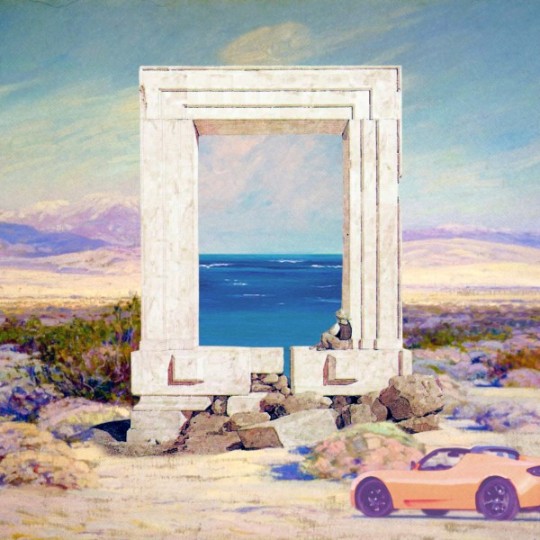

Daniel Keller: Seasteading is a portmanteau of Sea and homesteading. It is the concept of building semi-permanent cities at sea, usually in international waters and armed with novel socioeconomic and legal systems. It’s sold as the optimal libertarian solution to the lack of innovation in government. Yet its essentially a fantasy escape plan for a permanent minority to circumvent a representative democracy, which is inherently unsympathetic to their devotion to tax evasion and secession.

Libertarians argue that the Federal government should consider itself a ‘public option’ provider of “citizen experience” in the governance industry, and open the market to competing options. Obviously no national government is going to let this happen within their borders, so the idea is that they might, for some reason, just go ahead and tolerate it as long as it takes place in international waters. So a seastead is seen as the only way to lower the barriers of entry to the “governance industry” which are insurmountably high in any sovereign (land-based) nation. These platforms would ideally be built modularly so that citizens or groups could merge and split off to form new seasteads in the constant search for their optimum-blend society. (Islands having sex with other islands, then divorcing them).

Alessandro Bava: Since the 15th century, understanding the legal and political status of the sea has been a struggle. Political philosophers like Hugo Grotius and Carl Schmitt have produced, in very different times, theories to define the immense and fluctuating body of water in terms of power relations. The renewed interest in seasteading seems to reignite that struggle by trying to inhabit the voids left by contemporary regulations on the sea, in times of global political instability. Do you think the seasteading option is a form of new colonialism, and in a way interprets current frustration with traditional governance models?

Martti Kalliala: I don’t think the colonial lens necessarily sets a meaningful frame in which to understand seasteading – even though you could say it’s rooted in a narrative sequence beginning with Manifest Destiny (then hitting the Pacific Wall, and reopening the idea of the frontier via a literal application of Blue Ocean Strategy).

But yes, frustration and anxiety for sure re: broken governance systems that have been experienced across the political spectrum. There’s a whole lot to be said about the current, and to a certain degree generational, disposition towards “exit over voice.” The tendency to favor opting-out over staying in, to create new structures rather than improve what already exists, to build a startup instead of a tracked career in existing organizations – or to start a new country. Exitcore might then be the aesthetic limit of utopia.

DK: I agree that the narrative basis of seasteading could be seen as a literal extension of Manifest Destiny off of the California coast and into the Pacific and beyond. But as opposed to classic forms of colonialism there aren’t any people out there being directly displaced or subjugated—seasteading has all the excitement and potential of a frontier without the humanitarian guilt. When I asked Peter Thiel about his interest in seasteading at the DLD conference a few years ago he framed it exclusively as fulfilling an emotional need for new exploitable frontiers as a catalyst for innovation and economic growth—first the oceans and then space.

AB: Is it untimely that such interest in the sea is “territorial” even in times when the biggest industries are non-territorial (i.e finance)?

MK: But the body is still territorial. And the banality and awkwardness of needing to deposit one’s physical body somewhere to be “free” is really fascinating: one would choose this total unfreedom and hardship that comes with living on an isolated platform in a corrosive, at times hostile ocean environment in exchange for a set of abstract, mainly negative freedoms. Culturally it’s a bizarre combination of settler machismo – battling the challenges of the life aquatic – and an almost autistic disregard for one’s physical environment – like whatever as long as there is soylent, hi-speed internet and a lax tax code.

DK: I think it’s a misconception that we’ve moved beyond the territorial. I think its similar to fantasies of the internet as immaterial when in fact it is an enormous, lumbering stack of physical infrastructure. This is also why I think people were so shocked by Russia’s territorial expansion into Ukraine— fighting for territory felt so retro. But even finance is super-territorial (not non-territorial). Enormous profits are derived from exploiting the differing ‘energy states’ between jurisdictions, through tax avoidance schemes like “the double irish” or the “dutch sandwich”, sort of comparable to a steam engine generating energy from thermal gradients. If the world was really post-territorial, this would no longer be possible. A uniform and post-territorial world would be akin to a state of maximum entropy.

AB: Martti how do you think seasteading is relevant in architecture, or rather how is architecture relevant to seasteading?!

MK: It’s pretty obvious how existing and historical architectural typologies of living and working could be applied in more intelligent and interesting ways compared to these naval engineer / archi-hobbyist designs that now circulate online.

More interesting is the fact that designing a seastead would mean collapsing spatial concepts such as country, city, neighborhood, territory, site and building into basically one architectural gesture. Or, at the other end of the spectrum, in a design where secession is possible down to the scale of an individual building or cell – a seastead as a kind of plankton raft of floating mini-steads – these concepts become almost meaningless.

AB: Theres something beautiful about imagining the sea horizon as the only view from your future window…is that just romantic? Or is it a generational phenomenon that arises from the implication of false ideas of limitlessness in technology, and the actual physical and phenomenological limitation we experience everyday?

MK: If it’s romantic, the ocean-as-image is also culturally (and apparently also biologically) imprinted with a host of associations that have been successfully appropriated by financial capitalism. Just think of concepts such as liquidity, offshore, Blue Ocean Strategy etc. and the imagery they are typically associated with. This is of course something that Daniel has been looking at a lot in his practice.

DK: Yes, I think the appeal of this imagery really boils down to an almost ‘lizardbrain’ attraction to blue and green landscapes. By employing that sort of imagery to illustrate entirely artificial concepts like liquidity, it lends them a sense of naturalistic inevitability. I imagine liquidity ‘looks’ more like cubes on a conveyer belt than a splash of refreshing aquamarine mouthwash.

AB: Martti recently you have rewritten Rem Koolhaas’ text ‘City of the Captive Globe,’ readapting it for seasteading, could you explain that connection?

MK: So the original text was an early hypothesis of the ‘theory of Manhattan’ written before Koolhaas’s seminal book Delirious New York. In it he abstracts Manhattan into its essential parts: a gridded archipelago in which each “science and mania” has its own plot. On each plot you have a base (platform) on top of which each philosophy can construct its own edifice, suspend unwelcome laws, facilitate speculative activity, etc. Here 1920’s Manhattan works as an ideological laboratory and an incubator of the world itself (the actual office and condo-filled Manhattan obviously failed to deliver on this hypothesis). Today of course the incubator is a startup incubator and the grid is the smooth unobstructed space of the ocean. So suddenly the text becomes the subconscious theory of seasteading…

While I understand the relative pragmatism of the Seasteading Institute – looking into solving the fundamental hard problems of settling in an ocean environment – which I’m sure is necessary for them to gain any mainstream acceptance, the potential of the seasteading imaginary is to a degree wasted on trying too hard to ‘make sense’ of it. It will probably never ‘make sense,’ and it shouldn’t. For it to be truly attractive I believe it ought to be explicitly charged with libido, excess, and insanity – essentially the unfulfilled promise of ‘Manhattanism’ as a kind of boiling aquaculture. So instead of the lock-in of the grid, a liquid substrate on which islands can copulate and produce mutant offspring, collapse, burn and rise again. And, why not resurrect seapunk as some kind of aesthetic practice of every day life?

0 notes

Text

SOLASTALGIA - Bea Fremderman - Dismagazine

Do you experience this feeling of dread in relation to ‘eco-anxiety’ on a daily basis?

I think my eco-anxiety has transformed into eco-paralysis. Meaning that I know the ecological problems that we are facing are larger than what we can control and I’m really unsure what to do about it on an individual basis. Changing my light bulbs, recycling and taking public transit can only do so much at this point. Only a much larger, top-down change must happen in order for us to prevent our planet from warming further.

How do you see your work and art practice in relation to the feeling that the direction the world is moving is beyond our control? Is it born out of hopelessness or hope?

I think my interest is born out of hope. Foreseeing or hoping for an apocalyptic ending is really a deep desire for a radical societal change.

What’s it like to work with materials that seem to corrode with time?

I knew I was working with ephemeral materials when I started the project and part of the process was seeing what would happen in time with the objects. What I found interesting is that I was using materials as metaphors for how nature takes over humanity and in the end nature did in fact take over the work and did what it wanted with it. The chia on the clothing died; the fruit dried causing the sutures to loosen up or tighten depending on the fruit; mold grew on the lint bowls and finally the brick wall sprouted enough cherry radishes that it uprooted the wall and partially collapsed. I knew the exhibition was going to change and there was nothing that I could do about it. That really adds to the show. Change is part of it, decay is part of it. Instead of seeing these changes as elements that take away from the work, I see them as an additive-process.

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

Explore art history by discipline, subject matter, style, movement, medium, time period, geographic region, and more

0 notes

Link

Eye on Design is an editorial platform that explores what it means to be a designer today. We cover the issues important to the global design world + elevate the voices of contemporary designers as a way to build a more engaged design community.

0 notes

Link

Fox News is the deciding factor in the polarisation of American politics, rather than social media or new conspiracy theories

0 notes