Text

Week 10: Social gaming

Social gaming is fascinating because, as De Zwart & Humphreys (2014) notes, the codes governing it are layered and complex, including game rules (user agreements), coded rules (restrictions on how you can play based on the physical parameters set by the code), and then the governing social norms of the real-world areas that the players are from. EVE makes a particularly fascinating case study because the premise of the game is to be rule-less; to obtain power by theft, intimidation, and murder. However there still are norms and rules that govern the conduct of the players, and the game creators noted that the game has naturally evolved from individuals operating as silos to corporations, with order, hierarchy and rules. The events of January 2014, where $300,000 worth of space ships were destroyed due to a virtual bill not being paid, resulted in players staying home from work to defend and rebuild their battalion (Thornhill, 2014). This shows how the lines between the virtual game world have blurred with the real world. While there are many valid concerns around people being consumed by online gaming at the expense of their “real” lives, many players find through these platforms a social network, community, and social structures that may make more sense to them than those in the real world. References De Zwart, M & Humphreys, S 2014, ‘The lawless frontier of deep space: Code as law in EVE online’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 77-99. Thornhill, T 2014, ‘The online videogame battle that cost $300,000: Gamers see hundreds of costly spaceships destroyed after user forgot to pay bill to defend their base’, Daily Mail, 29 January, viewed 4 June 2018, .

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

You make a really good point about peoples’ reliance on the information they find on social media in response to crises. Many apps and platforms are already responding to this by adding built-in features to facilitate this (such as Facebook’s Safety Check in), and emergency response networks tend to use the information on social media in partnership with verification methods, but for the average user who is taking any information on social media at face value, there is a really potential for trolls, or even interested parties such as political parties, to misinform the public and create havoc. Like you said, this is not such a threat in instances of natural disaster, but it is something to be mindful of during humanitarian crises like Ushahidi and the 2008 crisis in DRC.

Studying about crowdsourcing for our group project gave me a new appreciation of how valuable it is, and how much positive impact it has had on disaster relief efforts, so I hope that companies continue to invest in verification technology to make it even more effective and fool/troll proof.

#6 - Crowdsourcing in times of crisis

Crowdsourcing is a concept then enables a large group of people to contribute to an idea or cause (Hoßfeld et al., 2013). There are many examples of crowdsourcing, including branding and marketing ideas, such as the campaign by Nissan that allowed the public to name a vehicle, through to product development, such as the Facebook app that Citroen developed that enabled the public to input on key design aspects of a new car (Moth 2013). Other examples of crowdsourcing include solving scientific problems, such as the British Parliament and NASA have done (Dahlander & Piezunka 2017) and even creating television shows, such as Amazon Studios that enables individuals from around the world to submit their ideas for production (Barr 2010).

Crisis situations have also used crowdsourcing effectively, by harnessing the power of the wider population combined with technology such as social media to help report and disseminate information in real-time, such as the recent Queensland floods. The use of Twitter during the Queensland floods resulted in over 35,000 tweets that became a main source of information from the community, but was also supported by mainstream media and emergency services, creating a central, coordinating voice during the crisis (Bruns et al., 2012). This shows that crowdsourcing and social media can be used for positive outcomes in times of a crisis. Conversely, crowdsourcing and social media can be used to spread misinformation and it is important to ensure the information posted is verified, particularly in cases of political and humanitarian crisis, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo crisis of 2008 (Ford 2012).

Ushahidi is an example of the technology platforms that enable crowdsourcing of information to be easily created, including important features such as verification by other users of a report and also the ability to geographically map responses from the community to a live map, giving people the ability to easily visualise where the activity is occurring, known as social mapping (Gao, Barbier & Goolsby 2011). An example of the combination of crowdsourcing, social media and social mapping is evidenced through the use of Ushahidi during the Haiti earthquake in 2010, whereby the platform was used by the community to post information regarding individuals and also for emergency services to provide updates to the community (Ushahidi 2012).

Crowdsourcing and social media are certainly advantageous in many scenarios to invoke the power of the population through the use of technology and this holds true in times of crisis as well. The important factor in times of crisis, is to ensure the information is true and correct, as the affordance of the technology means that many people are relying on the information to respond to the situation.

References:

Barr, A 2010, ‘Crowdsourcing goes to Hollywood as Amazon makes movies’, Reuters, 10 October, viewed 26 May 2018, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-hollywood-crowd-idUSBRE8990JH20121010>.

Bruns, A, Burgess, J, Crawford, K & Shaw, F 2012, #qldfloods and @QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods, ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, Brisbane.

Dahlander, L & Piezunka, H 2017, ‘Why Some Crowdsourcing Efforts Work and Others Don’t’, Harvard Business Review, 21 January, viewed 26 May 2018, <https://hbr.org/2017/02/why-some-crowdsourcing-efforts-work-and-others-dont>.

Ford, H 2012, ‘Crowd Wisdom’, Index on Censorship, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 33-39.

Gao, H, Barbier, R & Goolsby, R 2011, ‘Harnessing the crowdsourcing power of social media for disaster relief’, IEEE Intelligent Systems, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 10-14.

Hoßfeld, T, Tran-Gia, P & Vukovic, M 2013, ‘Crowdsourcing: From Theory to Practice and Long-Term Perspectives’, Dagstuhl Reports, vol. 3, no. 9, pp.1–33.

Meier, P 2012, ‘The Ushahidi Hait Map in the first 24 hours after the earthquake.’ [image], How Crisis Mapping Saved Lives in Haiti, National Geographic, viewed 26 May 2018, <https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2012/07/02/how-crisis-mapping-saved-lives-in-haiti/>.

Moth, D 2013, ‘Eight brands that crowdsourced marketing and product ideas’, eConsultancy.com, 11 April, viewed 26 May 2018, <https://econsultancy.com/blog/62504-eight-brands-that-crowdsourced-marketing-and-product-ideas>.

Ushahidi 2012, ‘Haiti and the Power of Crowdsourcing’, Ushahidi, 12 January, viewed 26 May 2018, < https://www.ushahidi.com/blog/2012/01/12/haiti-and-the-power-of-crowdsourcing>.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Yet those whose social feeds are filled with their symbolic good deeds reap the same satisfaction of meaningful impact as those camping out in city centres”

I think this is so fascinating. Social media is in many ways a great platform to spread the messages of activism, but how much of it translates to real world change? The sheer size of these platforms means the impact must still be greater than campaigning purely offline (that concept seems completely bizarre these days!), but there is so much ‘clicktivism’ - I’m guilty of this too - and passive support that I think it can be misleading as to the real-world change that is going on. I like your point about people easily identifying as supporters of a cause when they can do so from a safe distance (just by liking or following a page), compared with those who actually turn up when necessary; attending protests, making petitions, and so on.

Clicking your way to freedom - does social media activism translate to real world change?

In 2011, Time Magazine named Wael Ghonim as one of the Most Influential People of the Year. Via a Facebook group he had led the call for thousands to take to the streets of Cairo, the start of a series of events that would inevitably lead to the overthrow of a 30-year regime (ElBaradei 2011). Reaching the masses via Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, this “Facebook revolution”, as the media liked to call it (Shearlaw 2016), was one of many events that would occur in the middle east and surrounding areas during the Arab Spring. Social media platforms proved themselves as an incredibly useful tool for mobilisation, as well as for spreading news to the outside world in a regime-controlled media landscape, setting the benchmark for future activists.

Indeed, two years later when revolution occurred again in Egypt, it was social media calls that brought the masses back to Tahrir Square (Shearlaw 2016). Across the Mediterranean, the people of Turkey too were feeling the buzz of the Arab Spring. When protests broke out in Istanbul, Twitter and Facebook became the primary sources of information for those occupying Gezi Park and foreign news outlets alike, circumventing the news blackouts sanctioned by the Turkish government and broadcasters (Hutchinson 2013). Rattled by the wavelike effect of social platforms, the Prime Minister of Turkey went as far as calling them a “menace to society” (Knibbs 2013). But looking back on these events, is it the hashtags or the images of thousands gathered in public squares that are burnt in your memory?

Whilst the likes of Facebook and Twitter undoubtedly played important roles in mobilising support, to credit them with the success of actual change is to do a disservice to those who were on the ground and their circumstances. In 2013, I decided to pack a bag and head off to Turkey and Egypt. Unbeknownst to me (or perhaps due to my inability to follow the news), I was about to waltz into two countries on the brink of revolution. I was quickly made aware of my error when I pranced out of my hostel in Istanbul on Day 1, straight into a cloud of tear gas – word to the wise, the term “tear gas” is a gross understatement of where exactly it’s going to hurt i.e. everywhere. On the day we went up to Taksim Square, we weren’t met with a mob of thousands, armed with their phones, fiercely tweeting, but rather a disillusioned public physically occupying a space, whilst being met with a violent pushback by police. The protests that defined these pro-democracy uprisings across the middle east certainly had social media in common, but so too were their factors of years of state repression and social issues, and a people ready for change (Shearlaw 2016; Youmans & York 2012, p. 316).

In the digital age, where the activist population is equipped with mobile technology, social media serves the same role that the newspaper or flyer did for previous movements (Gerbaudo 2012, p. 4). Offering a public space for expression and information distribution, anger, pride and shared experience combine in online forums and often translate into real world action (Gerbaudo 2012, p. 14; Youmans & York 2012, p. 315). Posting the locations and intentions of protestors on public forums, however, comes with its risks. Open to the public also means open to government security officials, and with that a risk to personal safety. These causes also fall victim to the trolls that run rampant on the internet and ever-present instigators of moral outrage. As put by Ghonim, when speaking about the current state of activism in Egypt, “the same tool that united us to topple dictators eventually tore us apart” (Shearlaw 2016).

Opening the gates of a movement to anybody who has a social media account also places unrealistic expectations on its success. The ease of action means users are quick to identify as supporters when it comes to clicking ‘Join’ or ‘Like’, or adding the odd hashtag to a selfie at a safe distance from the action, but not so quick to picket. Yet those whose social feeds are filled with their symbolic good deeds reap the same satisfaction of meaningful impact as those camping out in city centres – and this mentality trickles all the way down from revolutions to charity fundraisers. In fact, studies suggest that those who offer token support are no more likely at all to offer substantial monetary or physical contributions to a cause (Kristofferson, White & Peloza 2014).

youtube

In a society driven by likes and followers, and the perceived social status they award, adding the title of ‘Activist’ to your profile is all too appealing. Whether it boils down to laziness or a genuine belief that a retweet will feed a starving child in Africa or end a civil war, the role of social media in creating meaningful change is dubious. I appreciate the positive effects social campaigns like #MeToo and #NeverAgainMSD have had on raising awareness of existing social issues and mobilising supporters, but I’m yet to be convinced that social media really deserves the “revolutionary” praise it receives. But unlike almost everything else in my life, I’d love to be proven wrong on this one!

References

ElBaradei, M 2011, ‘The 2011 Time 100: Wael Ghonim’, Time, 21 April 2011, Available at <http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2066367_2066369_2066437,00.html> (Accessed 11 May 2018).

Gerbaudo, P 2012, Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism, Pluto Press, London.

Hutchinson, S 2013, 'Social media plays major role in Turkey protests’, BBC News, 4 June 2013, Available at <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-22772352> (Accessed 12 May 2018).

Knibbs, K 2013, 'Arrested for tweeting in Turkey: The social media machine of the #Occupygezi movement’, Digital Trends, viewed 11 May 2018, <https://www.digitaltrends.com/social-media/the-invaluable-role-of-social-media-in-occupygezi-and-protest-culture/>.

Kristofferson, K, White, K & Peloza, J 2014, 'The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1149-1166.

Shearlaw, M 2016, 'Egypt five years on: was it ever a 'social media revolution’?’, The Guardian, 25 January 2016, Available at <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/25/egypt-5-years-on-was-it-ever-a-social-media-revolution> (Accessed 10 May 2018).

Images and video

‘A man during the 2011 Egyptian protests carrying a card saying “Facebook, #jan25, The Egyptian Social Network” illustrating the vital role played by social networks in initiating the uprising.’ 2011 [image], Essay Sharaf, viewed 12 May 2018, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2011_Egyptian_protests_Facebook_%26_jan25_card.jpg>.

‘Hashtag activism’ 2017 [image], Eric Allie, Furious Diaper, viewed 11 May 2018, <http://furiousdiaper.com/2014/05/14/hashtag-activism/>.

‘Your ‘Like’ Doesn’t Help Charities, It’s Just Slacktivism’ 2013 [video], DNews, Seeker, viewed 10 May 2018, <https://youtu.be/efVFiLigmbc>.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great post! I think your point about thinking gamers are missing out on the offline world, when maybe it’s the reverse, is really interesting. I can definitely see a plausible future in which the digital world is considered more valuable than the physical world (and then we’ll all wear VR headsets and live out best lives as our avatars). I remember being fascinated by the Sims back in the early naughties, although I never played it: a game that was literally about creating a second world. Bizarre. What social gaming adds to this is you get to assume another character, but also interact in a real way with others and form meaningful connections and friendships. I imagine that having a character that you are playing might even free you up to be more ‘you’ in an authentic way in your actual interactions with other players.

Week 10: Social Gaming

The nature of gaming has changed radically over the decades. I recall a school friend receiving his first computer and a group of us would all travel to his place so we could play the latest role playing game on his computer in his family’s living room. We would all wait to take our turn, meanwhile watching and critiquing each other’s game. Today, you can now play on a computer, gaming console, tablet or mobile phone and with literally millions of people from around the world.

Specifically, online gaming has become sophisticated, enabling players to enter rich virtual worlds and assume identities that have meaning and purpose that requires ongoing dedication to keep the game running. One such example is EVE Online, an elaborate space-themed massive multiplayer online game (MMOG) with over 500,000 subscribers (Purchese 2013). It was created in 2003 and has been running continually since. This in itself is unique, being able to play a single game for over a decade shows how online games themselves have matured into being part of society, providing an outlet for so many people to dedicate their time and sometimes their money. The digital community that is created through the participation of EVE online extends to online discussion forums, annual conventions, a “player council” that represents players to the developers, magazines and even a “university” (de Zwart & Humphreys 2014). This ecosystem shows how like-minded people from around the world can come together and connect, share and participate in a virtual community.

Online gaming has been linked to a number of negative outcomes for individuals, such as isolation and excessive playing at the expense of offline activities, however, more recently, it has also been linked to a number of positive factors, such as social inclusion and the ability to extend pre-existing relationships (Trepte, et al. 2012). This is evidenced by the many gaming conventions that now occur around the world, bringing like-minded gaming enthusiasts’ together offline to share their experiences, network and interact with each other (Fisher 2018).

Personally, I haven’t played many computer games since those memorable times back in school, however, I am marvelled at the sophistication and scale that online gaming has become. I now wonder whether some of us is the offline world are actually missing out on what is happening in the online world, despite the arguments typically in the reverse.

References:

de Zwart, M & Humphreys, S 2014,’ The Lawless Frontier of Deep Space: Code as Law in EVE Online’, Cultural Studies Review, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 77-99.

Fisher, J 2018, ‘Get your gaming on at these upcoming 2018 video game conventions’, Geek & Sundry, 3 January, viewed 27 May 2018, <https://geekandsundry.com/get-your-gaming-on-at-these-upcoming-2018-video-game-conventions/>.

Fisher, J 2018, ‘Pax South’ [image], Get your gaming on at these upcoming 2018 video game conventions, Geek & Sundry, viewed 27 May 2018, <http://geekandsundry.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/pax.jpg>.

Purchese, R 2013, ‘Eve Online: 500k subscribers and what CCP learnt along the way’, Eurogamer, 28 February, viewed 27 May 2018, < https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2013-02-28-eve-online-500k-subscribers-and-what-ccp-learnt-along-the-way>.

Trepte, S, Reinecke, L & Juechems, K 2012, ‘The social side of gaming: How playing online computer games creates online and offline social support’, Computers in Human Behaviour, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 832-839.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think you’re so right that political discussions on social media have lost their sheen. The ability for anyone to make memes, political statements, and so on, mean that there is so much inaccurate information floating around, but your point about people not being interested in having their mind changed is really key. Comments sections either tend to be everyone agreeing with each other, or name calling. I feel that digital communities, while lauded for giving us the opportunity to expand our networks, and expose us to a diverse set of people, are actually more often giving us opportunities to find the most similar people to us, and spaces where our opinions will be least contested. The enormity of reach of social platforms is actually making our worlds narrower, simply because we can find ‘our people’ and not have to face differing views, or if we do, it’s completely acceptable to respond to those views with vitriol and insults.

Politics and civic cultures.

Social Media can be a powerful tool for political campaigning for both politicians or political activists. In recent years we’ve seen a darker side emerge with hacktivists harnessing that power to influence the US presidential elections with fake news as well as the scandalous Cambridge Analytica use of Facebook data. The days of ‘Kevin ‘07’ and Obama’s ‘Hope’ campaign seem like a distant memory.

2007 was a time when social media was really taking off in the public sphere. Sites like Facebook and Twitter were still relatively new and incredibly popular among younger people. Obama’s victory can be directly attributed to his ability to tap into the youth voting base and even Facebook seems to be aware of its new role in political discourse having launched a forum to encourage political discussion around this time (Dutta & Frazer 2018). I myself was in my late 20’s at the time and I remember feeling quite optimistic about the future. I followed Kevin Rudd on Twitter and Facebook and I was ecstatic when he won (the disillusionment would come later).

Fast forward to 2017 and the atmosphere had changed. Political campaigning had become more commonplace with almost anyone being able to post political memes, be they factual or not, or simply share content from sources they favour. In my view it’s become decidedly adversarial with a more openly hostile tone. Take for example the recent posts made by Nationals MP George Christensen just days after a mass shooting in Florida where he posted a picture of himself aiming a gun with the caption ‘Do you feel lucky Greenie punks?’ (Nothling 2018) or Donald Trumps Twitter rants. I’m certain that it’s the politicians feeding this phenomenon. Needless to say, I no longer engage in political discussions on social media. No one is interested in having their mind changed, they are only interested in being right so most political discussions degrade into slanging matches. It’s just bait for trolls.

References:

Dutta, S & Frazer, M 2018, “Barack Obama and the Facebook Election”, US News, viewed 3 June, 2018, <https://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2008/11/19/barack-obama-and-the-facebook-election>.

Nothling, L 2018, “‘Do you feel lucky, greenie punks’: George Christensen under fire over Facebook post”, ABC News, viewed 3 June, 2018, <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-02-18/facebook-post-mp-george-christensen-feel-lucky-greenie-punks/9459476>.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really enjoyed reading this Kate, although it’s not fun subject matter. You make a really good point about digital communities meaning your network is always with you, and I think this is what makes cyber bullying and trolling so harmful - it doesn’t go away at the end of the day (unlike playground bullies, who you would at least get respite from at home). It’s interesting that the prevalence of trolling and cyber bullying has almost made it more acceptable, in that it is considered an inevitability of online interaction, but what concerned me most is that kids are now bullying themselves, that it has become its own form of social currency. This makes it much harder to police and manage also.

Dealing with cyberbullies in the online playground

Not so long ago, the internet was a very different place. In the year 2000, it was all dial tones and askjeeves.com, and social connectivity meant sending emails back and forth. Now the internet isn’t so much a tool as it is an augmentation of ourselves, where your online presence is just as (if not more) important, as your physical presence. Your friends, family and strangers alike are always with you, in a digital form at least, ready and willing to offer their two cents with the click of a button. But in this new virtual space, the rules are somehow different. There’s no need for niceties or genuine human interaction, and ethical norms and social conventions are challenged and renegotiated every day (boyd 2012, p. 75). We live in an “economy of attention”(McCosker 2014, p. 203), and being seen and heard matters above all else.

Code Name Melania - click here to see the rest - it’s worth it

Cyberbullying and trolling are hot topics in the media these days. Even Melania Trump, has named fighting cyberbullies as her chosen cause (an interesting choice, for obvious reasons). Taking schoolyard fights online is the norm now (boyd 2014, p. 130), following kids home with a relentless verbal bashing in the palm of their hand. And it’s not just the youths that have gone wild. Fully grown adults are tearing each other apart all over the internet from the comfort of their own homes, some more sinister, and others just messing with people for fun. Our inability to be decent human beings when given a platform has reached epidemic proportions, but the question remains – is this a social media issue, or have our real-world conflicts just found a new home?

youtube

My schooling experience seemed to coincide with a major shift in online behaviours. In primary school, I had nothing more than an e-mail address (cyber_kitty – in hindsight a terrible idea) and a Neopets account. My tweenage years saw a boom in instant messaging, and the couple of valuable hours of internet access I had each afternoon were spent discussing (and causing) drama amongst my friendship circles. The scariest things on the internet were perverted chat rooms, which I was strictly forbidden from entering. LiveJournal, Bebo and MySpace changed the game though. Suddenly our young lives and tortured teenage souls were on show to the outside world and an influx of ‘anonymous’ users. Meanness had always existed, but on notes passed around the classroom or in a lunchtime gossip session. With social media though, the attacks could come from anywhere and anyone, long after the school bell had rung. The difference for my Nokia 3310-wielding generation though was that we had the choice to disconnect – an affordance that isn’t plausible for many in 2018.

These online behaviours have serious consequences. Studies suggest that over 33% of youths in the U.S. have been the victim of cyberbullying and that young victims are twice as likely to attempt suicide and/or self-harm. Most alarmingly, there is a rising trend of young people bullying themselves via anonymous or fake social media accounts (boyd 2014, p. 141; Fraga 2018), perhaps for attention or maybe to validate their own feelings of hopelessness. There is no doubt that young people, who seem particularly attached to their devices, are especially susceptible to these kinds of attacks, however, it is also important to consider that many victims are often also perpetrators (Ewens 2017). The veil of anonymity that platforms offer, combined with this strange perceived notion that online activities don’t have real-world consequences, have taken “freedom of speech” to a scary new level. This “cyberbullying” umbrella term has also blurred the lines between plain old conflict and downright harassment, further changing our perceptions of how we are allowed to treat each other, and what the ramifications will be when we do so (boyd 2014, p. 132).

Bullying and general nastiness have always existed. And there is no doubt that this new constant state of connectivity and public exposure has upped the ante, and unpoliced social media platforms are the weapon of choice. It seems inappropriate to approach this as a “social media issue” though, and nor does it seem right to say our antics have moved to a “new home”. There is no longer a separation between cyberspace and the physical universe, and with the affordances of constant communication, it makes sense for an exponential rise in meanness to coincide. I see no end in sight, as platform-based regulation can only ever truly be as effective as our own abilities to be decent human beings. And is logging off truly worth the risk of becoming invisible?

References

boyd, d 2012, ‘Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle’, in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

boyd, d 2014, It’s complicated: the social lives of networked teens, Yale University Press, New Haven, USA.

Ewens, H 2017, 'The Ugly Evolution of Cyberbullying’, Vice, 1 September, Available at <https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/gyy8kq/the-ugly-evolution-of-cyberbullying> (Accessed 22 May 2018).

Fraga, J 2018, 'When Teens Cyberbully Themselves’, NPR, 21 April, Available at <https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/04/21/604073315/when-teens-cyberbully-themselves> (Accessed 22 May 2018).

McCosker, A 2014, 'Trolling as provocation: YouTube’s agonistic publics’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 201-217.

Images and video

‘Celebrities Read Mean Tweets #7’ 2014 [video], Jimmy Kimmel Live, viewed 27 May 2018, <https://youtu.be/imW392e6XR0>.

‘Code Name Melania: Secret Agent Fighting Cyber Bullying’ 2017 [image], Ward Sutton, The New Yorker, viewed 27 May 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/humor/daily-shouts/code-name-melania-secret-agent-fighting-cyberbullying>.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“hell, I eat dinner, go to the gym, pat dogs, etc as much as your average mid-level influencer”... this made me laugh out loud! I was so interested by your comment about filers grooming us for plastic surgery down the track. It seems impossible to me that the ubiquity of social imaging hasn’t created a more self-conscious and vain population. I think looks have always (sadly) mattered, but now personal branding matters and looks are a huge part of that. One of the affordances of social media is that being a bit obsessed with yourself has become completely normal now - I remember simpler days when selfies weren’t a thing, or if they were, they were almost shamefully narcissistic. As much as I would love Murray’s hypothesis of women claiming back their looks and bodies to be right, I think that this phenomenon is more about validation than empowerment.

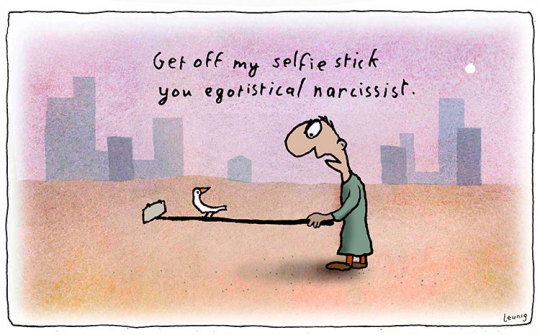

#myauthenticfabulouslife

Camera phones and social media – name a more iconic duo.

It seems almost impossible to remember a time when snapping a picture of your dinner wasn’t the norm. When the term “selfie” didn’t exist, and photos existed only in albums and frames scattered around your grandma’s house. When you were lucky to get even one photo of your mug each year, and it would be distributed to friends and family far and wide as visual evidence of your growth and achievements, tucked inside the annual family Christmas card. Trying to explain this concept to people who have grown up with the back of an iPhone pointed at them makes me feel older by the second. “Back in my day, you had to walk a mile to get your film processed, and when you got them back, half your photos were unrecognisable”. Somewhere in my house, there’s a box of cameras gathering dust that have been ruled obsolete. There’s no time for developing film or searching for camera cables – posting a photo more than 24 hours after it was taken will warrant a #throwbackthursday or #flashbackfriday. We need photographic evidence of our fabulous lives, and we need it right now.

youtube

Social media has become an important tool of social self-formation (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), providing us with a means to archive moments that we deem important enough to share with the masses. Visual media has turned everyday life into a public performance (Khamis, Ang & Welling 2017, p. 199), a vapid competition of whose content can generate the most attention, in a world where content is abundant and attention, depleting. With every like, comment, and follow, we are reaffirming social conventions of what merits our attention and why (Lange 2009, p. 70) – and narcissism wins every time.

During the process of social media taking over our lives, the concept of public vs. private got lost somewhere along the way. This constant state of connectedness brought with it an expectation of constant exposure and self-disclosure (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), and from that we have somehow construed that every second of our lives is worthy of sharing. Scrolling through your Instagram feed, it’s not uncommon to find a never-ending stream of gym selfies, lunch pics, bathtub selfies, dog pics, #ootd selfies, sunset pics, and selfies “just because”. Our curated lives – allowing us to be seen exactly as we’d like, no matter how edited or misleading. And while it is fair to assume that we can strike up the perfect mix of FOMO and admiration with a pretty vacation picture, the most intriguing phenomenon of all is our fascination with posting pictures of ourselves. Studies suggest that selfie culture exists predominantly amongst young women, and there are a multitude of explanations on offer. Is it out of pure narcissism? A need for validation in a world where self-esteem seems to be at an all-time low? Some suggest that it’s the deliberate act of women claiming back their bodies and independence in a voyeuristic man’s world (Murray 2015, p. 490). Whatever the reason, we’re all here for it. A recent study has determined that pictures containing our faces are 38 percent more likely to bring in the likes, and 32 percent more likely to attract comments.

With the popularity of shameless self-promotion on Instagram, a whole generation of social media “influencers” has risen from the sea of likes. Bypassing the traditional gatekeepers of celebrity status, your ability to rack up followers has become the standard for measuring fame and success (Khamis, Ang & Welling 2017, p. 198). And our willingness to take their photos at face value has come at a cost, reaffirming - perhaps to a greater extent - the standards of beauty and good living that have long been enforced by traditional media. The constant bombardment of (usually carefully staged) selfies has been hugely detrimental to self-esteem. And in our own efforts to emulate, plastic surgeons have noted that apps that allow us to filter our appearances are grooming us for plastic surgery down the track, and children as young as three are already working on perfecting their poses (Diefenbach & Christoforakos 2017, p. 2).

It’s a strange contradiction when sharing more of our lives online also means sharing less of our real, authentic selves. I personally don’t post many photos of myself online, not because my life is particularly uninteresting (hell, I eat dinner, go to the gym, pat dogs, etc as much as your average mid-level influencer), but because production expectations for an Instagram-worthy shot are far beyond the level of effort I’m willing to put in. This is not to say I am above the anxieties that come with social media posting that affect the best of us. With every photo I share, the question remains - am I just posting for the likes?

References

Diefenbach, S & Christoforakos, L 2017, ‘The Selfie Paradox: Nobody Seems to Like Them Yet Everyone Has Reasons to Take Them. An Exploration of Psychological Functions of Selfies in Self-Presentation’, Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1-14.

Khamis, S, Ang, L & Welling, R 2017, 'Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers’, Celebrity Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 191-208.

Lange, PG 2009, 'Videos of affinity on Youtube’, in P Snickars (ed.) The Youtube Reader, National Library of Sweden, Stockholm, pp. 70-88.

McCosker, A & Wilken, R 2014, 'Social Selves’, in S Cunningham and S Turnbull (eds), The media & communications in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 291-295.

Images and video

‘How Millenials Became the Selfie Generation’ 2018 [video], The New Yorker, viewed 31 May 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3_CHnYg-yc>.

‘Selfie Stick’ 2016 [image], Michael Leunig, viewed 3 June 2018, <http://www.leunig.com.au/works/recent-cartoons/688-selfie-stick>.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 9: Visual communities and social imaging

Images have become a fundamental part of the fabric of social networks. Not just the photos that represent us, but the photos we send to each other, and tag each other in - I have some friends that I communicate with solely through tagging in funny photos or memes. While images have always been important resources for sharing our life stories, this has increased dramatically since the advent of social media and networking (Burgess & Vivienne, 2013). Where in days past, we used to go to Uncle Gary’s house to see his holiday snaps, he now uploads them onto Facebook with the same intention of sharing a part of his life experience. Images are no longer simply the subject matter of our communication, they are a new form of communication, particularly with the advent of apps like Snapchat (Herrman, 2014). The fact that images can be created and shared in real time creates an overlap of our physical and digital communities, and the idea of these two worlds being separate (one ‘real’ and one ‘virtual’) is highlighted by Jurgenson (in Herrman, 2014) as being outdated.

Humans are motivated to engage with online communities by a need to belong and a need for self presentation (Nadkarni and Hoffmann, 2011), and images and photography provide a unique and efficient way to do this. The problem that Spiegel (in Herrman, 2014) identifies with this is the idea that we are “the sum of our published experience” that is, we start to define ourselves, and be defined, by the parts of ourselves that we share online. Where digital communities originated as a place to interact, and share our physical lives, now people curate experiences in their physical lives for the sole purposes of sharing them online. In this way, digital communities offer a place to create a new persona, whether that is an improved version of yourself, or a completely new identity. This, as Jurgenson identifies, creates a tension between experience for its own sake and experience we pursue just to put it on Facebook (Herrman, 2014).

Source: dopl3r.com

YouTube takes this further with the moving image. Videos of affinity afford the same ability to belong and self present. There is something thrilling about seeing a video of yourself - it is a way to see how others in the world see you, and it validates your own experience of yourself in the world. To then share that online and have other people confirm your existence and validity, is very powerful. As bandwidths get faster, and social networks offer more video-centric features, we will only move further in this direction.

It is interesting, then, that Snapchat is enjoying such popularity. When a big part of the appeal of social imaging is creating a representation of yourself online, and creating an online legacy, this app that features ephemeral photos and videos, that disappear in an instant. Speigel’s suggestion (in Herrman, 2014) that this is because images are now becoming the conversation, rather than facilitating the conversation.

References

Burgess, J E & Vivienne, S 2013, ‘The remediation of the personal photograph and the politics of self-representation in digital storytelling’, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 279-298.

Herrman, J 2014, ‘Meet The Man Who Got Inside Snapchat's Head’, Buzzfeed, 28 January, last viewed 2 June 2018, <https://www.buzzfeed.com/jwherrman/meet-the-unlikely-academic-behind-snapchats-new-pitch?utm_term=.fgM18g2oN#.nqrqQenMr>.

Nadkarni, A & Hofmann, S 2011, ‘Why Do People Use Facebook?’, Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 52 (2012), pp/ 243–249.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 8: Crowdsourcing - it used to annoy me because I’m a terrible person

When I was researching crowdsourcing for our group assignment, what surprised me was how ubiquitous it was and how, for the most part, it greatly annoyed me. I had previously thought of crowdsourcing almost exclusively as crowdfunding (which in reality is just a subset of crwodsourcing), but I realised it was present in many of my least favourite social media interactions: friends getting upset at me for not taking part in the ice bucket challenge; people posting no make up selfies; being spammed by people to vote for their baby/dog in baby/dog modelling contests; constant social media posts to raise money for this or that triathlon. I mean, well done everyone, you’re very brave/strong/motivated/your child is beautiful, but I don’t care and I’m really just here for the cat gifs so please stop clogging up my feed.

Real talk though: I challenge anyone to tell me - without looking it up - what the #nomakeupselfie was in aid of. Or what the ice bucket challenge raised awareness for. So it’s fair to say that I did not think much of crowdsourcing, and the above examples often seemed more about an individual’s vanity than an actual concern for a cause. None of my friends had ever shown a great concern for any of these causes before they offered a chance to be beautiful / hilarious on social media**.

Source: https://twitter.com/jtmlsn/status/446100295643189251

However, finding out that Shutterstock, the photo sharing website (which I use every day at work) and Wikipedia (oh, I would cite thee in every assignment if I was allowed to) are two early examples of crowdsourcing (Howe, 2006), suddenly I had a whole lot more time for it. Then when I started reading about the innovative ways in which crowdsourcing was used in response to natural disasters and crises, I started to see how valuable it could be. A simple, and very efficient, way of sharing information or directing the actions of those who wanted to help, for example the hashtag #bakedrelief was used after the Christchurch earthquakes to direct donations to where they were needed most.

Given that we now live in an always-on world, what became apparent during crises such as the Christchurch earthquake and New Zealand floods, was that news moved faster on social media than it did through traditional news outlets (Ford, 2012). Furthermore, the virtual communities that sprang up during these events helped bring a sense of camaraderie and support to those who were most directly affected. These instances of crowdsourcing developed quite organically, and led organisations such as QPS Media to look into setting up more systematic online crowdsourcing systems to harness the velocity of social media during crises, such as information verification methods (Bruns et al. 2012). Information verification is a crucial part of crowdsourcing during crises, with incorrect or intentionally misleading information potentially directing resources away from where they are needed most.

Source: http://www.performancemagazine.org/on-data-quality-and-crowdsourcing-calvin-and-hobbes/

Crowdsourcing has now become an in-built feature on many social media platforms (think Twitter hashtags and Facebook’s Safety Check feature), and most of us can’t remember a time when we didn’t turn directly to social media for information around these events. With the right tools in place, crowdsourcing has become a really powerful and positive affordance of digital communities.

**I realise I’m painting a picture of my friends as narcissistic jerks and they’re really not. I’m just trying to illustrate a point. #drama

References

Bruns, A, Burgess, J, Crawford, K & Shaw, F 2012, #qldfloods and @QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods, ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, Brisbane.

Ford, H 2012, ‘Crowd Wisdom’, Index on Censorship, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 33-39.

Howe, J 2006, ‘The Rise of Crowdsourcing’, Wired, 1 June, last viewed 18 April 2018, <https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/>.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 7: Send in the trolls

When I was at high school, MySpace was still several years away. For my friends and I, the new, sparkly internet was all about online chat rooms, and it was in many ways an extension of our friendships at school. Furthermore, we found we were able to be more of who we were in these chat rooms. A quiet group at school, we weren’t picked on but we certainly weren’t ‘cool’, and one of the affordances of chat rooms for us, was finding a place that we fit in, where we were deemed cool for being ourselves. Online bullying definitely existed then, but the concept of trolling was a few years away from being well-known. To me a fundamental point about trolling is that is not always targeted like bullying is; while bullying falls under the umbrella of trolling, trolling also has a broader audience: trolls often simply have the intention of causing havoc and upsetting anyone (Phillips, 2015) - the more the merrier.

Picture: Amazon

Part of the appeal of social media, and of having access to a much wider network than is afforded to you in your physical world, is the potential for validation. Strangers can connect with you over shared interests, you can garner thousands of likes on a witty comment or flattering photo - short of being a celebrity or a performer, there is probably no offline equivalent where you can amass such validation. However, the flip side of having access to this invisible audience is that they can also be negative, and cruel - even more so because they can do so without revealing their identity. This wider audience can also have a knock-on effect of other people joining in, which can increase the trauma of the targeted individual (boyd, 2014); in fact even the expectation of support from their peers can encourage someone to post in a trolling manner (Bastiaensens et al. 2014).

The issue is that, in some ways, trolls are behaving as all digital citizens do: engaging and responding to conten’t around them, albeit in a destructive way. Commenting and sharing are fundamental affordances of most digital communities, and there is no real way to filter trolls out while maintaining those affordances for everyone else. Furthermore, this brings up problematic questions of what should be allowed under the right to free speech, and what level of conflict is healthy versus problematic (McCosker, 2014). And as we’ve spoken about earlier, the affordance of anonymity is also an important one for many people in online communities; not because they want to cause conflict, but because it allows them a freedom of expression that they would not otherwise have access to.

So what to do? Do we just accept that trolling is an inevitable side-effect of freedom of speech in the social media age? When we react to trolls, we inevitably give them more fuel and air time which is arguably just the kind of attention they’re after. My mum used to say to me that the worst thing you can do to a bully is not react, and maybe that’s our best bet with combatting trolls too.

References

Bastiaensens, S, Vandebosch, H, Poels, K, Van Cleemput, K, DeSmet, A & De Bourdeaudhuij, I 2014, ‘Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 31, pp.259-271.

Boyd, D 2014, 'Bullying: Is the Media Amplifying Meanness and Cruelty?', in It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, Yale University Press, New Haven, USA, pp. 128-52.

McCosker, A 2014, YouTrolling as provocation: Tube's agonistics publics, Convergence, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 201-217.

Phillips, WA 2015, ‘This is why we can’t have nice things: mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture’, London, England: The MIT Press.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 6: Don’t Blame Me, I’m Gen Y

I was reading a great article on the weekend about Generation Z; specifically the students who were involved in the protests following the recent school shootings in Florida. The article suggested that the reason that this generation are so politically active is out of necessity; they have never known a time when America wasn’t at war with Iraq & Afghanistan, unlike Gen Y, they didn’t grow up in the optimism (and consequent passivity) of a post-war era.

This, combined with the fact that they are digital natives, goes a long way to explaining why digital activism is so ubiquitous now. The largest generation is also the one who feels empowered to make change.

Furthermore, the frameworks of social platforms lend themselves to creating memorable political messages - namely, hashtags. Most of us know instantly the various campaigns that the following hashtags are from: #yeswecan #metoo #neveragain - hashtags are the new buzzwords. These hashtags become relevant even for people who don’t have or use the platforms they originated from (like me). I don’t have Twitter and would not call myself an active contributor on any of the social media platforms I use. I tend to just lurk and like other peoples’ posts! However, these hashtags are all meaningful to me because they became bigger than their platform - not just on other social media platforms but in mainstream news media, clickbait articles, BuzzFeed, and so on.

What’s more, these campaigns reference and call for real-world action. Lynch (2011, in Youmans & York, 2012) identified four ways in which social media contributed to collective activism, and this is a key point: digital activism is only useful if it leads to meaningful action. It can generate momentum and support, but in cases where this does not result in real changes, such as the KONY 2012 campaign (the video achieved massive popularity and reach, but Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony was never apprehended), people can feel let down and misled. In the instance of Invisible Children’s Find Kony campaign, they raised over US$20 million, but spent more on marketing than on finding Kony (Truthloader, 2012).

Image: Hijacked

The thing about activism is it comes from a place of discomfort. The people most active in the #neveragain campaign are the people most directly affected by it: the students. In Syria, locals are using citizen journalism to gain reach and worldwide support to help overthrow the Assad dictatorship (Youmans & York, 2012).

From my position of middle class privileged comfort (and Generation Y passivity), it is easy for me to admire from afar - I am a classic slacktivist. I do care about these causes, I’ll sign a petition and even attend a rally every so often, but I am not the driving force behind them. What social media has done is allowed anyone to be that driving force. You don’t need a lot of traditional resources to utilise the power of social media for activism - you just have to have a message that resonates.

References

Lester, A 2018, ‘Generation Z: Politicized by necessity and already changing the world’, The Age (Good Weekend supplement), 28 April, viewed 28 April 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/world/north-america/generation-z-politicised-by-necessity-and-already-changing-the-world-20180424-p4zbcu.html>.

Truthloader 2013, Joseph Kony 2012: What happened to invisible children?, viewed 28 April 2018, <http://bit.ly/1pk3M06>

Youmans, W & York, J (2012), ‘Social Media and the Activist Toolkit: User Agreements, Corporate Interests, and the Information Infrastructure of Modern Social Movements.’, Journal of Communication, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 315-329.

0 notes

Text

Week 5: Politics and civic cultures

I never used to be that political. For a long time, my interest in politics began and ended with House of Cards, and I’d never included my political views in my Facebook ‘about’ section. But that is changing - I can feel myself becoming more interested in politics. Maybe this is partly because the political climate has become incredibly volatile in the past few years, maybe it’s because the characters in the game are more engaging / ridiculous / terrifying than they have ever been. Or maybe it’s because, without having to try, I have unprecedented access to political information and opinions in a way I never did before. I don’t have to read the newspaper (I was always a ‘skip to the comics page’ person) to be up to date on political information, because it presents itself through my social platforms, through friends’ comments in my newsfeed, funny memes, or click-bait headlines that lure me in. For me it feels like the internet really has become a democratising force in politics (Young, 2010), although evidence suggests that this new level of access does not necessarily mean a more representative audience, particularly for Indigenous Australians, and people employed in low-skill occupations, who have significantly lower access to broadband internet (Young, 2010).

Politics has become a pervasive and powerful part of social media. Features are built into various platforms to allow you to display your political views: during the 2016 US Election, you could add a frame to your profile picture on Facebook that announced your political alliance. Our political views have always been part of our private identity, but with the rising influence of social media, they are increasingly becoming part of our public identity. Political events such as marches and rallies are organised on Facebook, and political news is accessed, shared and discussed. In an era when so much time is spent on social media, it seems only natural that voters turn to these platforms for their political news.

And it’s not just the voters: politicians and grassroots political movements are increasingly using social media platforms to reach a wider audience (Jericho, 2013). However, in order to utilise them effectively, they need to respond in real time to political issues to show themselves as genuinely engaging and avoid being seen as spam (Jericho, 2013).

But here’s the thing: the accessibility of politics on the internet does not necessarily expand our political ideology. We decide who we like and follow on social media, and algorithms determine what we read and engage with, and show us more of the same. We are likely to only see a very narrow slice of the political diaspora: one that aligns with our existing values; or, more dangerously, as seen in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, manipulates and shapes our values. We have gone from being political consumers to commodities.

References

Jericho, G 2013, Rise of the Fifth Estate: Social Media and Blogging in Australian Politics, Scribe Publications Pty Ltd., Carlton North (ProQuest).

Young, S 2010, How Australia Decides: Election Reporting and the Media, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne (ProQuest).

0 notes

Text

I too grew up in a generation of walkman users, and had to check the Melways before I left the house to know where I was going. I often find it concerning to think about Millennials who grew up not knowing a world without social media. To me there is a danger in creating an online presence before being fully aware of how truly public the online world is, for example: even if you post a photo of yourself to a closed group, there is nothing stopping someone else in that group from sharing that photo with another group, and so on... with regards to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, I find it interesting that I’ve been complaining for at the least the last two years about how creepy Facebook’s targeted advertising is (when you look up shoes on asos, then next time you visit Facebook, there’s an ad for them), but it never occurred to me that my data and online behaviour might be tracked and used for much more serious and world impacting reasons (like election outcomes). And at what point does this stop being fair game, if I’m the one clicking the ‘I Agree’ buttons to Facebook’s privacy policy without ever reading the fine print, and I’m the one posting publicly about my private life?

Facebook is no longer comfortable.

I belong to a very specific generation, somewhere between Gen X and Millenials, who happened to have been born between 1976 and 1983. We grew up in the time before the internet and mobile phones. We remember when you used to go to a friend’s house not knowing if they were home or not. Talking for hours to our friends on the landline phone. Sending and receiving letters. We were the first generation to embrace the internet. We chatted on MSN or Yahoo messenger. We learned to code with Myspace and saw it superseded by Facebook. It’s been interesting to observe the way these technologies ingratiate themselves into our lives and society.

According to McCosker and Wilkin (2014) Social network sites “enable constant communication and connection, while encouraging increasingly public levels of self-disclosure or exposure.” This means that we are using these platforms to enable us to stay in constant contact while at the same time encouraging one another to disclose more personal information. But according to Mandiberg (2012) “Humans are both curious and social critters. We want to understand and interact. Technology introduces new possibilities for doing so”. While many may assume that we are addicted to the technology, Mandiberg tends to see it as facilitating and enhancing human interactions (Mandiberg, 2012). In my own experience as of late I’ve been quite concerned about the privacy of my Facebook account. I don’t use many social media platforms, I have a Twitter account which I barely ever use. I use Facebook quite frequently but when the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke I’ve wanted to delete my Facebook account but found that the connections I have with friends from all over the world were too valuable to just throw away. I have a lot of friends who I can communicate with cheaply in real time from places like America, Pakistan and South East Asia and it would truly pain me to lose these connections. Sure I could move to a different social network but there’s no platform as commonly used or easily accessible as Facebook. I guess this is what is meant by the term ‘social capital’, but who is really capitalising? Is it us or is it Mark Zuckerberg?

References:

Mandiberg, M. 2012, The Social Media Reader. NYU Press, New York. ProQuest Ebook Central. Viewed 14 April 2018 <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/swin/reader.action?docID=865738&ppg=84>

McCosker, A & Wilken, R 2014, ‘Social selves’, in S Cunningham & S Turnbull (eds), The media & communications in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 291-295.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really interesting points here. I particularly enjoyed your comments on Turkle’s views, being able to edit & delete means we’re losing the art of interaction. I also wonder if this means we’re gradually losing the ability to sit with discomfort - the discomfort of disagreeing with someone’s views (you can unfollow people if you don’t like what they’re saying), the discomfort of caring about something that is not cool (not displaying that part of yourself on social media) and so on. I think the fact that we can make our online lives so comfortable for ourselves might ultimately have a negative impact on our ability to interact in the real world - for example if we work with people who have different values or opinions to us, we can’t literally block them out of our work day as we can do on social media.

I’m the same as you in that I really value social media as a way to reconnect with people from my past, or stay connected to people I am separated from by time or distance. For me this outweighs the negatives (or I have a social media addiction :) hard to say for sure) but I wonder how we might combat the narrowing or our online world in our everyday lives.

Blog Post #1 - Social Media

Social media, for many, has become part of everyday life. According to Cowling (2018) 60% of Australians are active Facebook users, whilst 50% are active on YouTube and 30% are active on Instagram.

There are many social network sites that facilitate sharing and each provides a service that enables individuals to maintain a profile, which can then be shared with others (Murthy 2013).

Being able to share information and associate with a community of people that share a mutual connection to something – geography, interests, political views, events and educational or professional interactions, has changed the way society interacts, learns and communicates (Siapera 2012). A key question, is it redefining human connection?

One argument is that the pervasive use of social media disconnects us from the real world and the reality is that social media can not only change what we do, but can also change who we are (Turkle 2013). Turkle argues that the addiction to social media may have negative consequences to how we relate to each other. The concepts the Turkle offers for consideration include #beingalonetogether – able to customise your life. #hidingfromeachother – people are too busy to interact in a meaningful way. #goldilockseffect – not too far, not too close, just right. Social media allows us to edit and delete, meaning we are losing the art of conversation and live interaction. It gives us the “illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship”.

Social networking tools allow us to manage the aspects of our lives that we wish to make public to others, enabling a highly managed and edited view of an individual (Wilken & McCosker 2014).

Boyd (2012) presents an argument that social media and technology allows us to be connected to information and people in whatever context we choose. She refers to being “always on” as the ability to create networks of people and information to satisfy our curiosity to understand and interact.

I personally agree with aspects of Turkle (2013) and Wilken & McCosker (2014) in that much of what is shared on social media is the information you have specifically selected to share with your network. It is often the perfect holiday photo, the filtered social photo at a desired location or the amazing meal you just need to tell everyone about. On the other hand, I find social media invaluable at keeping in contact with friends and acquaintances I have met throughout my personal and professional life. This likely reinforces Boyd’s (2012) argument of satisfying curiosity and the desire to interact.

References:

Boyd, D 2012, ‘Participating in the always-on lifestyle’, The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, pp. 71-76

Cowling, D 2018, Social Media Statistics Australia – December 2017, Socialmedianews.com.au, viewed 7 April 2018, <https://www.socialmedianews.com.au/social-media-statistics-australia-december-2017/>

Murthy, D 2013, Twitter: Social Communication in the Twitter Age, Wiley, pp. 1-13

Siapera, E 2012, 'Socialities and Social Media’, in Understanding New Media, Sage, London, pp. 191-208

TED-Ed 2013, Connected, but alone?- Sherry Turkle, 19 April, viewed 4 April 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rv0g8TsnA6c>.

Wilken, R & McCosker, A 2014, 'Social Selves’, in Cunningham & Turnbull (eds), The Media & Communications in Australia, Allen and Unwin pp. 291-295.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I laughed out loud at that eecard, Kate :) (where is the LAUGH button on Tumblr??!) I am really interested in boyd’s idea of assumed transparency that you discussed, especially in terms of celebrities and the expectations on them to be consistently active on social media. If they give us (followers) enough of what we want can they then forge out private time, while the rest of us are using our private time to curate the best looking public life?

I also liked what you noted about us being able to customise our lives. I think the interesting flip side of this is that we customise them so much as to be blindsided by events outside of our values and demographics (for example, American left leaning voters on Facebook were largely following and interacting with likeminded people and so did not necessarily see the rise in support for Trump, and were ulitmately unprepared for his win - data scandal notwithstanding). I know I experience this in my own online interactions. I wonder how dangerous it will end up being if we’re all creating online worlds where we only see what we want to see.

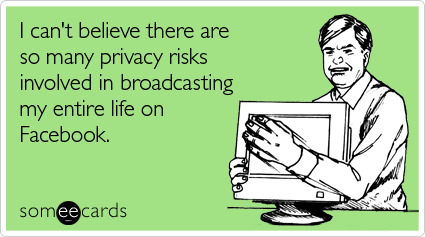

Our Public Private Lives

It seems our days of prolific brunch documentation and oversharing shan’t be behind us anytime soon. A 2015 survey found that the average online individual actively uses 2.82 social media platforms – 5.54 accounts per person and rising (Mander 2015). Collectively, we share 95 million photos and videos on Instagram every day (Osman 2018), creating a never-ending feed of selfies, puppies, meals, and sunsets. Social media has become an essential tool of social self-formation (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292), serving our longing to connect with others, whilst fuelling our relentless need to share every detail of our lives.

youtube

Perhaps the greatest affordance of the reign of social media is our ability to customise our lives. Producing our own content means that we are in control of how our profiles, or our lives as seen by cyberspace, appear (Siapera 2012, p. 198). All aspects of our online existence are malleable, from our friendship circles to our interests and affiliations, where this data can then be used to track down other individuals of similar circumstance, wherever they may be. This “networked individualism” removes us from geographical constraints, allowing us to form “communities of choice”, and extending the reach of our content to a global audience (Siapera 2012, p. 199). Our levels of openness, as well as our negotiated online appearances, can be altered to fit our audiences (van der Nagel 2013), raising the question of whether there is a clear distinction in this modern world between what is public and what is private.

As social media usage continues to climb, so do our levels of public exposure and self-disclosure (McCosker & Wilken 2014, p. 292). Feeling the pressures of the constant drive to produce content, many seem to believe that broadcasting everything from the traffic they’ve encountered to their workout schedules is appropriate in the social media sphere. But are we engaging in this behaviour to feel connected to others or for fear of ceasing to exist if we fail to participate (Siapera 2012, p. 205)? The term “Facebook official” has become part of our vernacular, implying that if it has not been posted to social media, and thus broadcast to the world, then it isn’t real. Disagreements and grievances are being taken online, whether it be for convenience or to share our experiences with the masses. An entire generation of social media influencers have been born, encouraging people to participate in real-world activities just “for the gram”, and the perceived social validation that comes with an influx of likes and followers. In this strange new world of publicness, it seems that the more you are perceived to share with the world, perhaps the more private you can be as your audience assumes transparency (boyd 2012, p. 76).

Issues of online privacy have been brought to the forefront recently, as our personal data is increasingly harvested, sold, and then thrown back at us for manipulation. Our incessant desire to share products we like, political affiliations, and our locations with our social networks has meant that not only can our online shopping experiences and advertisements be personalised and targeted, but so can the news and political dialogue we are exposed to. Social media platforms are perhaps the biggest offenders in the undisclosed sharing of data, to the extent that this past week, Mark Zuckerberg has been giving congressional testimony. But isn’t it ironic that we are so horrified by the concept of our personal data being breached when, really, it’s only available for corporate use due to our own willingness to broadcast it?

References

boyd, d 2012, ‘Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle’, in M Mandiberg (ed.) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, New York, pp. 71-76.

College Humour, Look at this Instagram (Nickelback Parody), 10 December 2012, viewed 13 April 2018, <https://youtu.be/Nn-dD-QKYN4>.

Mander, J 2015, Chart of the Day: Internet Users Have Average of 5.54 Social Media Accounts, Global Web Index, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://blog.globalwebindex.com/chart-of-the-day/internet-users-have-average-of-5-54-social-media-accounts/>.

McCosker, A & Wilken, R 2014, 'Social Selves’, in S Cunningham and S Turnbull (eds), The media & communications in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp. 291-295.

Osman, M 2018, 18 Instagram Stats Every Marketer Should Know for 2018, Sprout Social, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://sproutsocial.com/insights/instagram-stats/>.

Siapera, E 2012, 'Socialities and social media’, in Understanding new media, SAGE, London, pp. 191-208.

Images

'Daily Cartoon: Thursday, November 9th’ 2017 [image], Farley Katz, New Yorker, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/cartoons/daily-cartoon/thursday-november-9th-marathon-forest>.

'I can’t believe there are so many…’ [image], Someecards, viewed 15 April 2018, <https://www.someecards.com/cry-for-help-cards/i-cant-believe-there-are-so-many-privacy-risks-involved-in-broadcasting-my-entire-life-on-facebook/>.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2: How are our social experiences bound up with social media platforms and their affordances, and how we make use of them?

Here’s another question: how aren’t they?

Social experiences in the information age, if not lived entirely through social media platforms (such as chat rooms, online gaming, and blogging) are often documented on them; furthermore, our enjoyment of an experience can become intertwined with how well it was received on our social media platforms. Sometimes the process of documenting an experience can get in the way of actually experiencing it - we’ve all stood behind the person at a gig who films the whole event on their mobile. I’m not certain, but I feel confident that they’re not going home and rewatching it later - they’re filming it so their followers can know what a great time they had.

Get out of my way, you jerk. Photo by Elliot Teo on Unsplash

Have you ever deleted a Facebook post because it didn’t get enough likes? I have. I rarely post on social media because of this; I’d rather not be beholden to the social validation monster that is the likes machine at all, but I’m human and we all like to be liked (here is one of my favourite blogs about that), so my way to manage that need is to minimise interactions with it entirely.

Social Validation Monster. Drawing by me.

Obviously, it’s not all bad: social media platforms have given us new ways to access information, support, and friendships. They increase involvement in political and voluntary activities and causes (Saipera 2012, p. 203), and studies have shown that online interaction strengthens our offline networks (boyd and Ellison in Saipera 2012, p. 203). These increases in participatory and social capital show that the affordances of social media platforms have gone beyond their original design; they offer people opportunities to engage, safe spaces in which to express themselves, and access to social experiences they can’t get offline.

One of the most interesting affordances of this is the ability to be anonymous, or to create a whole new identity. This allows people to express themselves in ways that may not be accepted in their offline networks; whether it’s articulating differing religious points of view, or posting nude photos on Reddit. Humans crave expression free from judgment, and online communities allow us to find those niches for ourselves. Now, “people can choose what to reveal depending on their audience” (van der Nagel, 2013) - that is, the anonymity afforded by social media platforms allows people to manage separate contexts, and explore different aspects of themselves.

Social media platforms also allow us to create a legacy - an online archive of our life. This is particularly observable in blogs where people are documenting their experience of living with serious illness. Blogging allows people to share their journey, offer and receive support, and develop public intimacy (Kitzman in McCosker & Darcy, 2013 p.1268), where self expression is able to be shared and accessed by a wider community.

So, how to navigate our online experiences? Social media gives us unprecedented opportunity to find new networks and outlets for self expression. However as Pipuru (2009, in van der Nagel 2013, p. 7) cautioned, “once something is on the internet you have to give up hope on any other control of it”. To quote one of my favourite (NSFW) ad campaigns, maybe the best approach is to “explore - but protect yourself”.

References

Macleod, D 2008, ‘AIDES – Explore But Protect Yourself’, ads for adults, November 30, viewed 14 April 2018, <http://advertisingforadults.com/2008/11/aides-explore-but-protect-yourself/>.

McCosker, A & Darcy, R 2013, ‘Living with Cancer’, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 16, no. 8, pp.1266-1285.

Saipera, E 2012, ‘Socialities and social media’, in Understanding new media, Sage, London, pp. 191-208.

Urban, T 2014, ‘Taming the Mammoth: Why You Should Stop Caring What Other People Think’, Wait But Why, June 13, viewed 14 April 2018, <https://waitbutwhy.com/2014/06/taming-mammoth-let-peoples-opinions-run-life.html>.

Van der Nagel, E 2013, ‘Faceless Bodies: Negotiating Technological and Cultural Codes on reddit gonewild’, Journal of Media Arts Culture, vol. 10, no. 2.

1 note

·

View note