Text

Summary Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Ayano Honda, October 8th, 2019

The final meeting ended. Overall, it was very interesting to talk with classmates about the topics around the papers, including other topics while getting sidetracked. The conversation surely helped me understand the topics deeper and gain more insights.

Yesterday, given the theme of inevitable materiality for all humans and designers, we were discussing how designers (and engineers as well) are very powerfully responsible in regulating the ways how people physically interact with products. For example, I was not able to use the cheese slicer in my early days in Finland because I could not use my hand properly as the designer prescribed. Not only a cheese slicer but everything - I spent some clumsy moment to figure out how the roll-towel works and the Finnish dishes-drying shelve over the sink amazed me how simple and practical it is. These are just my funny experiences of getting to know “another material culture” abroad. However, we agreed that designed products could be quite exclusive when they take it for granted that the users have a particular condition and availability. Responsibility turns into morality.

I remembered that one Japanese package designer speaking in an interview that “if I design a chocolate’s wrapping paper even 1mm shorter, this means I might save a forest.” (his tone of voice does not sound humble which is not nice.) This is not mentioned particularly in the context of human-nonhuman relationship, but this suggested what the responsibility of a designer is. We, 2D persons, also tried to think how graphic designers (illustrators as well) could take material responsibility. But we never came to a conclusion.

In the end I would like to write a summary of the course too. Reading piles of works by designers, philosophers, and sociologists felt very distant from my own practice in the beginning - however, now I am very happy I have done! The concepts mentioned in each text looked pretty much like a cloud floating in the air that I can never touch or catch, however I gradually came to realise that it is indeed soil I am standing on. It is very hard to think about soil itself while walking in a forest (because I only look at trees and leaves and birds and sometimes horses), but it is surely underlying there.

They are also on strike!!

。

。

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Ayano Honda, October 7th, 2019

For the very first time, I looked back at how I had formed the relationship between myself and the material world. As surrounded by full of material entities, my behavioral patterns are very dependent on how tools/machines/devices expect me to act, totally out of my consciousness. The material world is thoroughly organized and standardized, as a result of the continuous effort in the human history to “eliminate unnecessary expenditures of energy” and to “maximize efficiency”, as mentioned in the essay Workers of the World, Confirm! by Nader Vossoughian.

Vossoughian discusses how the units of weights and measures regarded as the world standard today - such as meter, gram, Fahrenheit, A4 sheet paper - were internationally invented with the aim of bringing distant workers together and therefore advancing technology and economics more. Making a standard everybody’s obligatory standard is not an easy job since “no world format can function without a world that accepts it”. The author notes how a massive power asserts its authority in order to make the world obey the standard; the author takes an example of Nazis Germany’s operation that prohibited the citizens to use anything that were not applied to an A4 format with increasing “mandate for orderliness and efficiency was intensified”. The author's tone of voice is so pessimistic that he argues us being a “single world brain” and losing “business love, hatred, and all purely personal, irrational, and emotional elements which escape calculation.”

What is problematic here?Have we lost something in exchange for the convenience “world standards” offer us? Well, for me, my second language English is a sort of the A4 format. Maybe I am sacrificing my compromise; I use the foreign words as a universal format that I assume is corresponding to what I want to mean. Sometimes I cannot express what I want. Even when I find the words, they might never be exactly same as the expressions in my mother tongue, however, I put expectation that it would be close… in a way, maybe I am living in a bit of a metaphorical world. I use an A4 format sheet because I expect that it would be scanned and copied without an unnecessary margin or would fit in a document folder from Flying Tiger. For me, using authorized standards does not make me sad. In spite of that, during the process of adjusting myself to the standard, I am inevitably dropping something I don’t even know, at the same time I am surely benefitting from.

The intense observation on a door by Bruno Latour was also about the human’s attempt to create a universal format - the convinience brought by technological advancement - that sets humans free from hazard and labour. He looks at machines as the replacement of humans that could control undisciplined human behaviours. However, even the nonhuman substitutes are supposed to be convenient and helpful, machines still have new defects and inconveniences that requite more advancements. In my opinion, this may suggest that nothing can discipline humans and eliminate human random behaviours in a true sense, even though man-maid authority such as a seatbelt and an automated door tells us how to act. Needing a format while escaping form the format… this paradox seems to be representing the nature of human.

Lastly, OOO - object-oriented ontology - suggests grasping the world in a way that everything exists remaining equal status without any hierarchy. Valuable/trashy, material/concept, fiction/nonfiction... we automatically calculate and label all things around us, however, they are probably what we create in our mind, as a standard on a quite personal level. Or aren't they...?

0 notes

Photo

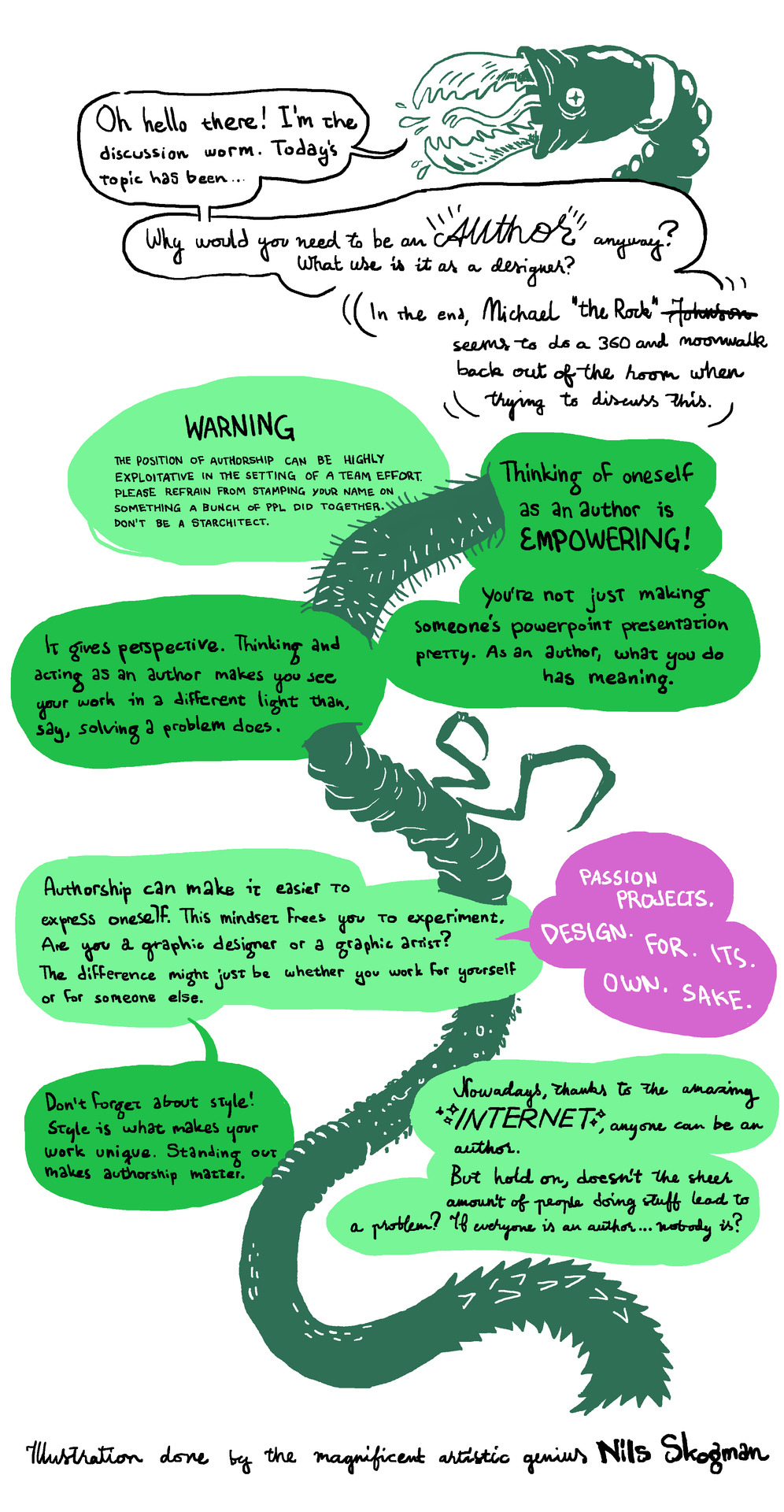

Summary Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Nils Skogman, October 7th, 2019

0 notes

Text

Summary Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Sabina Friman, October 7th, 2019

For our final group meeting, we met up at Oodi to discuss materiality in relation to design, based on the three texts by Ian Bogost, Nader Vossoughian and Bruno Latour. We agreed that the readings for this week were easier to compare and discuss because of the tangible nature of the topic itself, but also because the link between design practice and materiality is indisputable, if not obvious.

We started the discussion from the blog post on object-oriented ontology by Bogos by questioning why our philosophies are often so human-centric that they to a large extent, if not completely, ignore to take into account the world around us. Like all organisms, either human or non-human, we exist, take up space and make up this larger entity – a universe, if you will – of which we are but a part. Bogost is a writer and author, but it was his game designer identity which inspired us to look at the example of a game called ”Everything” that Nils introduced to us. In this game, the player can assume the role or point of view of any character, and that really means any; from humans, to animals, bugs, plants, islands, planets, stars, particles and so on. As I understood it, there is no other point to the game but to explore and to exist. To us, this emphasised what the concept of OOO is about; understanding our place in the world through the lense of things, and vice versa. And that for one, the concept of being human is not as self-evident as we might think it is.

This raised a brief thought about religious beliefs of the afterlife, where it is believed you can take the form of anything else in your next life. And certainly, how beliefs of morality affects that type of world view. We were getting a little side tracked with the big questions in life, so on the que of morality we turned our focus toward the type of morality Latour discussed in his text. We agreed that certainly, there is more to an object than the pure function of it. For example, most shoes have basically the same function, but how we interact with them can vary wildly depending on how they’ve been designed. To me, this reflects the morality imposed ontot he object by the creator. As Latour discusses in his text, it is inevitable we as engineers – and in our case designers – imbue our values into the things we shape, and so indirectly affect the people interacting with our creation. This gives the designer power, for good and for worse. Latour points out that through this and in the worst case even objects can become discriminatory.

But, as often is the case, these texts use examples that link to other fields and types of design, which we thought can make direct application to graphic design a little tricky. Graphic designers don’t necessarily make physical objects in the same way as an engineer or achitect does, so how do we think about materiality within our practice? I think a lot of it has to do with the origin of our profession, which takes us back to the text written by Vossoughian on the way paper standards came to shape the world. We agreed that by setting standards on paper and all things following, incredible power has been given to those deciding on them. Standards are of course practical and efficient, but by their very nature they make our world less diverse, and in many ways less human.

This got us thinking of other standards, some which have been ”universified” with more success than others. English has had a wide reach as a global language, whereas Esperanto, though still being used, never had quite the same success. In many ways this boils down to power and how English was spread through colonization, and not because it would have any sort of linguistic superiority by virtue. ”There is no standard without a world that accepts it” writes Latour, exemplifying the need for those with power to create such a world, even if by force. Esperanto never belonged to any one power, and thus never had the same outset. So it got us wondering, is there no middle ground in harnessing the benefits of standards, while still leaving room for richness in? We ended with a playful suggestion of legos; they can certainly be seen as standarized objects meant for play, but ones that enable children to build while still leaving the result up to the imagination. So is an ideal standard one that allows for diversity?

0 notes

Text

Summary

Reading III: The New Materiality of Design

Laura Kamppi, Oct 7, 2019

For our final discussion, we met today morning at eleven o’clock in Helsinki Central Library Oodi.

This time we tried if we could discuss one text at a time and then move on to another, because we have not tried that yet. Although, this time we all agreed that the texts connected well with another and there probably were not really a need to discuss them one by one and found it more interesting to talk about them all together perhaps, but at least now we have tried this type of discussion.

What is Object-Oriented Ontology? by Ian Bogost

We started by talking about the game called Everything that Nils mentioned in his introduction, because in the game, you can experience the world from different perspectives, even from the perspective of a building and this game relates to OOO, because the game also rejects the claims that human experience is at center of philosophy

There is no one “right” perspective

Getting to experience the world from different perspectives is ever so intriguing

Our experience of the world and our perspective is evolving constantly

Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts by Bruno Latour:

There is more to the object than the function. For example a shoe’s main function is the same, but the design of it expresses so much more than that. The difficulty level of putting a shoe on already determines how we perceive it, for example is the shoe meant to appear casual or not. And then there are other aesthetic values and such that all signals different things about the shoe

An object or a thing we make always reflects the values of the maker

No object or a thing is neutral

Question of the morality of an object

Workers of the World, Conform! by Nader Vossoughian:

After reading this text, we were all impressed by the power of stardards and I think we all learned something new

The morality of standards, technology has always good and bad sides. On one hand, standards make the world less diverse, because we also lose some point of views in the process of standardization, on the other hand standards bring more efficiency to the distribution of knowledge

Standards are kind of an inhuman concept to begin with if people are trying to forcefully standardize everything

Standards do not really exist if people don’t want to use them, this brings a lot of power to the people that make standards. For example Apple is powerful company, because they can use their standards to push and conform people, only to keep buying their products, because they make their products compatible with each other.

One example on standards is also euro currency. It brings the sense of comfort to use euro for example in EU countries.

Imperial vs Metric system for measuring

Legos were also mentioned as great example how Legos are are based on a certain standard, but the standards are just there as a base for creativity, diversity arises from standards

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Nils Skogman, October 6th, 2019

This week's reading has been all about the material world and how we relate to it. More specifically it has been about the material world of humans, the artifacts and materials and all that other good stuff we make. "Things" is maybe what one would usually call them, but I think it's a bit of a too limiting term.

I tried to write my thoughts about humans' curious relationship with our things and tools previously, but it's so complicated and intertwined and circular in all matter of ways, that I'll have to simplify it for anything to make sense both for myself and for anyone else reading it.

Basically it boils down to this: Even if we're not alone to make tools and shape our own environments in the animal kingdom, our relationship with our creations is quite unique. When a chimpanzee uses a twig as a termite fishing device, its use ends then and there. Tool used, stomach full, problem solved, let's go home and climb or something. For us, however, it doesn't end there. We don't just ignore the changes we've achieved, we're also changed by them ourselves. So we change our stuff in responce to the stuff we already got. And that changes us. And we change it. And so on and so forth. Thing is, this is what all of technological evolution is all about. It's a never ending feedback loop of humans making stuff, changing humans making new stuff, changing humans yet again. And that is what ultimately is the cause of change in all of society as well.

Speaking of society being human and thing interaction written large, let's talk a little bit about that. If we accept what our guy Mr. Bruno Latour writes about his dear groom, what implication does this have if we apply it to the entirety of civilization. To me it seems that every invention and every artifact is just a continuation of a previous thing that didn't quite work as expected, and this new version is an attempt to make stuff work better. Sometimes the next thing opens up new possibilities and so other new things and professions and what not fill those recently opened gap. All of this happens all the time at different paces and so new stuff needs to be patched in to fill the role of something other now yet to be invented. It quickly becomes a hot mess of uncontrolled improvisation with a symphony orchestra playing over here and a punk band jamming over there all the while some more influential people fighting over who gets to control this whole situation and nobody winning. Everything is linked to everything else and feeds back into the whole chaotic machinery. Society is a messy botchwork with patched in temporary and permanent solutions and temporary solutions that have become permanent (and vice versa) everywhere. Just like the nature it arose from.

Anyways, where do we designers fit into all of this? What are our responsibilities as the shapers of things? What powers do we weild in this seemingly calm but actually really chaotic world? Before reading this week's texts I wouldn't have thought much of it, but now I do really think we can have quite an impact. Design is after all not purely cosmetic. It's in fact very functional too. And whatever is designed, it's how it is used by a human being that makes the difference. This is where we can make a lot of difference. Maybe just as much as the engineers do, and that sure seems to be a lot.

The philosophy of OOO reminded me of David O'Reilly's game "Everything". It looks like a game born out of this way of thinking. No thing is more important than any other thing. In it you play as, well how do I put it, everything. Not at once of course. That wouldn't work. But you can really play as anything in the world. And the world is big. You might start off as a camel and walk around a bit. Maybe you talk to another camel or honk at a lion. But then you decide to be a grasshopper instead. Then you walk around chirping and hopping, maybe even let the computer do all of this for you if you want to. And then you again want to do something different and decide to be a barn or a continent or a dumpster or hydrogen. You explore the whole entirety of everything, from tiny scale of photons and abstract quantum foam to the gargantuan size of galaxy clusters. All the while you can find and listen to audio snippets of Alan Watts talking about the nature of everything, how you are the universe and the universe is you and how it all is connected, that identity is just as much of an illusion as time itself is. You know, regular everyday stuff like that.

Link to ze game here. It's pretty cool you see --> http://www.everything-game.com/

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading III: The New Materiality of Design Sabina Friman, October 6th, 2019

The material nature of design as a discipline is something we as design practitioners are well acquainted with. For us, it is the natural connection between our ideas and their execution, be it in the analogue or digital realm. Because the connection between us and the physical world around us is frankly indisputable, so is the designer’s role in shaping this material reality equally so. But this type of thinking goes both ways, for it is not only we who shape that around us, but that around us which in turn shapes us.

The three final texts of this course all grapple with the idea of materiality through different topics. In his blog post Ian Bogost – author and game designer – writes about object-oriented ontology as a way of studying, in short, the existence of things, while Nader Vossoughian – author, architectural historian and theorist – writes about how standardization has shaped the world we know today. Bruno Latour – philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist – discusses the way technologies, even those as simple and mundande as a door groom, have an effect on the way we are in the world.

In his text What is Object-Oriented Ontology? A definition for ordinary folk, Ian Bogost attempts to define the complex philosophical discipline of object-oriented ontology. His motivation for this particular task seems to have been inspired by a personal experience where he failed to adequately summarize and concretize the concept of OOO, something I can relate to in a way. Whenever someone asks me to crystallize what it is I do as a designer, expecting an elevator pitch perfectly adapted to their understanding of the field, I find it hard not to oversimplify and resort to desperate clichés to avoid glassy eyes.

Anyway, at first Bogost offers a broad definition of OOO as the ”philosophical study of existence”, a study that puts things at its center. He then offers concretizing examples and narrows the definition to the study of the nature of things, their relations with each other and that between them and us. He admits his attempt as a ”massive oversimplification” that ignores both the history and current trends of philosophy, but as a debatably necessary one to return ”the attention of philosophy to the real, everyday world”. Although I’m hesitant to the choice of words in the title (”ordinary folk” just seems a tad patronising), I agree with him on the importance of anchoring theory to physical reality as in the end, ”academia has a responsibility to the public interest”.

In Workers of the World, Conform!, Nader Vossoughian discusses the need that arose from industrialized society to restructure itself for the sake of maximizing efficiency. The ideal of such a liberated society meant for knowledge to be documented and circulated seamlessly through universal principles and organized systems. Different ideas on how to achieve this was presented, but in the end one solution prevailed; paper standards, or World Formats, or DIN 476. The fundamental link that Vossoughian explains was drawn between paper formatting and intellectual capital appeals to me. In a way, I see the standardization of paper as a standardization of our profession as well – maybe even the creation of it.

Of course, standardization does not always equal total universality, as proven by Vossoughians statement of the United States and Canada not having adopted the global paper standards even today. Even when converting, say, recipe measurements, one can get a sense of the limited universality of certain of concepts. No matter how annoying this can be in practice, the idea of it gives me a sense of comfort that there still are things that don’t fit the prescribed and made-up standards of the world, and that don’t need to be efficient in order to be valuable. Design can fulfil a purpose in many an unstandardized way.

Latour, in his peculiarly humorous tone of voice, tackles the topic of materiality through what resembles OOO to a large extent in Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts. He looks at how ”artifacts can be deliberately designed to both replace human action and constrain and shape the actions of other humans”, and delves into extensive analysis of everyday technologies such as door grooms or seat belts to prove how intertwined our societies are with these often unremarkable but necessary technologies. Although I found the text unneccessarily repetitive on the one hand, Latour managed to underline in many ways the more than hybrid nature of society; the collective and inseparable nature of us and the things we’ve built around us, the human and the non-human as equal actors that work together. For designers, I think the emphasis lies in the morality we transmit to the things we design, the values we instill in the things we shape, that in turn affect the people who end up interacting with these things. We truly are, or eventually become, what we create.

0 notes

Text

Introduction

Reading III: The New Materiality of Design

Laura Kamppi, Oct 6, 2019

The first text that I read for this time was a What is Object-Oriented Ontology?, a definition of object-oriented ontology by Ian Bogost. Since I am not that familiar with the term I looked into the Wikipedia article that Bogost mentions, but I it was written in a language that was quite hard to understand and I know now what Bogost means, when he says “it’s not really meant for public consumption.” Bogost’s definition describes that ontology means the philosophical study of existence and that object-oriented ontology puts things at the center of this study. The study uses speculation to characterize how objects exist and interact.

To my understanding, the next text Where are the missing masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts by Bruno Latour could go to some category of object-oriented ontology, because Latour is for example philosophically describing the function of a door groom to the reader.

I think the the most important points connected to a designers role are already brought up in the introduction part, where it says:

“His (Latour’s) study demonstrates how people can ‘act at a distance’ through the technologies they create and implement and how, from a user’s perspective, a technology can appear to determine or compel certain actions.”

I believe this to be true as one kind of an definition to what designer actually does “acting from the distance”. This rings true, especially in means and platforms created towards users, where the user actually makes the content. And as I far as I have come to known, these kind of tasks are needed from a designer today, creating a space of a platform for other people to act and make their own. The need to the democratisation of tools comes from peoples need to express themselves. Designers can aid that expression by using tools that they already know or by trying to create new tools. What would these new tools be? Machines? What kind? Designers after all, are the ones that can use their own observations and show alternative futures. Join the discourse of speculation and what will be.

One kind of employment of technology here that I am most concerned, is the use of internet as a tool. The part in the introduction where it says that technologies play an important role in mediating human relationships, I immediately start to think of how much phones have mediated our interaction and relationships with one another. We are also using our phone’s apps for all kind of knowledge. We get important information of our surroundings through our phone, we navigate with it. My phone is definitely an example of a machine that affects the way I perceive things and I don’t even notice it most of the time.

I found a connection in Latour’s texts to Nader Vossoughian’s text Workers of the World, Conform!. As Latour’s text “exlores how artifacts can be deliberatly designed to both replace human action and constrain and shape the actions of other humans.”, Nader’s text is also very much about that, when he is talking about the role of computers in the working life for example.

According to the text German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald suggested in 1912, that the world’s information should be standardized in order to harmonize all knowledge. The standard paper formats express an ideal: “With the right technical adjustments and systems, society can not only be salvaged but liberated.” The computer has standardized in turn the whole communication, in doing so, many tasks in many professions can be mainly done with computers and there is no need for material engagement.

I think this standardization is interesting. In my opinion, this connects to the democratisation of tools of a designer. Everyone that has a laptop and access to adobe software, can be a designer? What could a designer use to differentiate themselves? This also connects to the craftmanship of designer that we already discussed. Through engaging with objects, a designer can start to develop knowledge? Learning through making, one can internalize knowledge better? Through print one can start to find their own voice? Through experimenting and manually replicating things, one can realize what is their relationship with different machines or tools that we use also differentiate themselves of other printed matter and digital work.

I felt like this text and Bruno Latour’s text were perhaps the most educational to me of all the other text in this course. By reading Vossoughian’s text, I learned that paper formats led to the standardization of many other things as well, such as buildings or the dimensions of sidewalks.

It is intriguing to know little bit about the history of something that is so everyday to me and think about how these things work. I have never thought about the function of a door groom like how Latour describes it with such enthusiasm and precision.

0 notes

Photo

Summary Reading II: Design and Knowledge Nils Skogman, September 30, 2019

0 notes

Text

Summary

Reading II: Design and Knowledge

Laura Kamppi, September 30, 2019

On our 2nd meeting the discussion topics went something like this:

Spreadability of ideas. We talked about religion as an example

Talking about memes was quite easy and clearly the most approachable topic to discuss, since we are all so used to see them used everywhere

The “truth” in images, we mainly just asked more questions

Knowledge gained through images. I wanted to express my interest here to different interesting parts of Johanna Drucker’s text

Can it be said that visual language more widely understood than written language?

Nils said something interesting about information. Should all information be widely understood?

Is it true that when looking at an image you are automatically processing the knowledge, without you even noticing it, but in reading instead, you have to consciously process more information

Visual language is more prone to interpretation?

We all agrees that images help us in learning new things, we associate things more easily together by visual means

We all found the comparison to biology in James Gleik’s text intriguing. It is interesting to think about what kind of images stand the time if we are looking at it from the biology point of view, comparing the survival of images to the survival of species

Where are technological achievements heading towards in the future?

What would the future of pure craftsmanship be like? What does it look like? Could craftsmanship win over capitalism ever?

Signs of the time: Slowing down, (for example going to a pottery class in order to work with your hands) vs. Pushing onwards the thriving technological achievements

Progress for its own sake is useless

0 notes

Text

Summary Reading II: Design and Knowledge Sabina Friman, September 30th, 2019

Because I have been abroad during our group meeting, I’ve taken alternative measures in writing this. I’ll be basing my summary on observations from Ayano’s, Laura’s and Nils’ introductions and meeting notes (and partially summaries), alongside discussing the topic of knowledge and/in design with my travel partner. In both our textual and verbal discussions it’s been apparent this subject is everything but straightforward. It definitely makes you think again – and again, and again – about what the implications are or can be for your own practice, implications derived through the type of thinking introduced in these three wildly different texts.

As the rest of my group also found ”Into the Meme Pool” by James Gleick to be, perhaps, both the most intriguing and the most unsettling of the texts, I’ll start here as well. After explaining the context and meaning of Gleicks writings to my travel partner, we got into a discussion about the difficulty of determining how concrete/serious Gleick was in his analogy on the similarities between organisms and information. We both had a hard time agreeing with him on that this could be anything more than a metaphor at this point, the concepts are simply too abstract. Yet, even thinking of this in terms of a metaphor was a little bit disconcerting. The effect of thinking about ideas and information in this way – that we as humans, organisms with consciousness, are merely vessels for carrying knowledge that somehow already exists – is that it takes away the feeling of control, and that in turn of autonomous agency. Especially as designers and creators I think we are often used to feeling motivated by the idea of authorship, where the feelings of originality, authority and discovery is something we take professional pride in and seek out as a part of our creative process. We even talked about this being a part of identifying oneself as a designer but also as an individual, for what are we without our thoughts, ideas and knowledge; mere aimless hosts or empty vessels?

However, after reading the group introductions I really grew to like the idea of symbiosis introduced by Nils, that was discussed during the group meeting as well. To think of knowledge not as inherent to being human, but also not as completely separate organisms or entities of their own, I think symbiosis describes a quite balanced relationship between us and our ideas. We thrive off of them, and they off of us. As a word, symbiosis already has positive connotations attached to it, while if we use words such as parasitic, infectious etc. like Gleick did in his text has a much more sinister ring to them. This makes me think his intention indeed was to be, as Ayano also pointed out, quite provocative in style.

Mills’ text was in a way easier to concretisize to my travel partner, as it is very much related to design practice today. He also happens to be a musician, and so was able to relate to much of it through the lense of creative work. The timelessness yet relevancy of the piece made it both inspiring and unsettling, as Mills of course wrote it from the point of view of the social critic he was known as. However, my travel partner felt his critique of capitalist society was quite radical and slightly one sided, very much antagonizing something we have all also created and benefited from in many ways, also as designers. Together we questioned the realisticness of Mills’ strategy, and the true difficulty of reverting to a society where designer’s have complete control of their own way of working, no matter how ideal. As Laura mentioned in her introduction, it is easy as a designer to feel overwhelmed. But no matter how overwhelming or difficult these topics are, I recognize the importance of questioning the status quo and agree with the others on the usefulness in this for developing our practices, potentially shaping the future role of design.

Drucker’s text on visual epistemology felt slightly harder to boil down, as she covers the subject quite thoroughly. But we got to talking about what I mentioned in my introduction, that is the implications of creating a somehow universal graphic language, systematic enough for a machine to learn. We discussed how already today we both, as designer and musician, feel technology is more than an essential tool for our practice; it might often be the determining factor in how the work turns out in the end. Of couse, we’re still the ones clicking the cursor and curating the outcome, but the development of automation for the sake of efficiency is there in almost any field in one way or another. It made me think of what Nils wrote, in relation to another text perhaps but that kind of applies here too; that although all ideas or, in this case, tools of creation might not be ”ours”, we still decide what to bring forth – we curate the outcome. And so, is that what being a designer is? Making new things out of existing ones, combining old ideas in new ways to create something new? So is creativity then really just surprising curation? And is the startup buzzword ”innovation”, implying revolutionary insight and change, any different from that at all?

I wanted to end there, but I think it’s still important to bring forth what my travel partner pointed out, that of the intuitive human input in creativity. The sensitivity by which we both reflect and affect our cultures, societies and worlds is something I want to believe machines will not be able to do. Until technology starts evolving on its own on a grand, irreversible scale, I think designers will remain something more than simply curators of information.

0 notes

Text

Summary Reading II: Design and Knowledge Ayano Honda, September 29, 2019

Our 2nd meeting happened at the Tiedekulma on Sunday evening; we settled down at a couch on the top floor where there was another big meeting accompanied by ABBA music.

It was difficult to find a place to start the discussion since each one of the essays was quite informative and independent. So we discussed one after another, however, we spent the most time on the Into the Meme Pool.

At first, we agreed that the gene-meme analogy was very mindblowing for all of us. We never came to a conclusion as this theory may not have a true/false answer. We found the text more like a what-if type of idea than a scientific argument - probably, we thought "master meme & subordinate human" theory cannot be as clear as Mendel's peas inheritance theory.

Sabina wrote: who is actually in control; us thriving on the information, or the information surviving through us?

Instead of deciding which is better than the other, we found it compelling to explain the situation with the word “symbiosis”, which Nils mentioned in his essay. It is a host-parasite-like relationship but benefiting each other somehow. When we applied this analogy to meme theory, "remedies and human" and "religions and human" were clear examples. For ideas to endure for thousands of years, people must find them worth owning - otherwise, the information goes extinct. We also hold the reins!

Next, we shared the pain to read the sorrowful text by Mills. Now we witness the irreparable defects on the monolith of the excessed materialism culture. It was stunning that he just precisely predicted the sad future humans debasing themselves to be economical animals... however, we found his suggestions less applicable to today; if a craftsman should only indulge the sheer joy of creation without caring daily bread, how does he survive? (As Laura mentioned, we do that as hobby. We enjoy it a lot.) For me, Mills, a sociologist and not a designer, appears to be speaking from the safe zone because he was never to take the responsibility for what a designer would lose by being a pure craftsman.

So, What's the society he searches for? What's the period in the history that the craftsmen and workmen enriched the culture and were appreciated by the society? Can we go back to the past without losing anything?

In the end, Johanna’s history of the invention of universal visual language. Laura extracted this line: "We no longer believe that everything that can be known can be seen any more than we believe in the “truth” of visual images.” We discussed in which occasions we still find visual images less ambiguous (=more comprehensive) than verbalized information. Examples: in my Suomi textbook, “omena” did not make sense by itself, but with the picture of an apple it perfectly does; or, I am not able to tell somebody how my grandmother's face looks like with full of words, but with a picture within 1second I can. There are areas where a language is a better storyteller than a visual image and vice versa.

We experienced a lot of jumps and leaps in the multi-dimensional space of imagination. Even though the gene-meme story is hard for me to accept because I want to believe in my free will, it is a good practice to try thinking in “another level”. I am more aware of the limit of depth and flexibility of my thinking after knowing the works by the people who traveled much further than me.

Today's word: symbiosis!

P.S. I still have a question about meme...

Knowledge tells us what is good/bad and true/false. Does knowledge also shape our emotion? Are we made to like what the knowledge tells what we should like? I think, no. I can even hate food that is known to be very nutritious ... which means I guess emotion and knowledge can contradict. Emotion is also a big factor that decides human behavior and decision :-o

Also, how knowledge differs from your own experience? Experience should be part of the knowledge because you know what it was. Does meme say that your experience is also from somebody else'?

------------------------------------------------------------

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading II: Design and Knowledge Ayano Honda, September 29, 2019

Ultimate goodness I think is the truth that is true regardless time and space. Looking back at the history, "truth" could be false and renewed sometimes (like Heliocentrism) but we have kept making an effort to achieve that. That should be for betterment of oneself, as an inperfect being. Truth is what I have been taught (or gained from experiences and errors of my own): in that sense, it comes from "outside". Can't I still call it mine, once after I digest it? Who can say that it is not mine but somebody else'?

In the sci-fi-like essay Into the Meme Pool, James Gleick looks at the evolution and propagation of knowledge among humans as synonymous with those of genes, which was theorized by an evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who coined the word meme. Dawkins’ theory “selfish genes” looks quite provocative for me; in short, the human body is just a vehicle of genes who satisfy their own sake to replicate, evolve, transmit, and flourish. According to him, just like the genes, knowledge also thrives using a human brain as their host: “When you plant a fertile meme in my mind you literally parasitize my brain, turning it into a vehicle for the meme’s propagation in just the way that a virus may parasitize the genetic mechanism of a host cell.” Here, the master-subordinate relationship, which we have firmly believed in, becomes totally upside-down.

We easily consider ourselves owning knowledge because we pay painful effort in exchange for knowledge, for example, a foreign language which is a huge body of theorized and systemized information. Since information not only jumps into the head but it goes away, we have to tame them so they stay inside the cage. This is why I think we unquestionably think we are the very owner of the knowledge. It is challenging to look at the world from the point of view of the knowledge himself; if the knowledge that we “temporality” borrow exists independently floating in somewhere else, and if it forcefully shapes our personality and behavior, are we still responsible for ourselves? Can the meme pool help us grow up, not only as a knowledgeable person but as a mentally grown-up person? Is the floating knowledge ultimate goodness?

The question “what is trustable goodness?” is raised in the essay Man in the Middle written by a sociologist C. Wright Mills in 1958. Mills shares a strong sense of crisis regarding the society that only seeks economical value, persecuting the sheer joy and excitement of creation that had been highly valued. Here he writes “For our standards of credibility, and of reality itself, as well as our judgments and discernments, are determined much less by any pristine experience we may have than by our exposure to the output of the cultural apparatus.” He discusses the tragedy of a craftsman being a salesman trapped in the never-ending loop that “operates more to create wants than to satisfy wants”. “Wants do not originate in some vague realms of the consumer’s personality; they are formed by an elaborate apparatus of jingle and fashion, of persuasion and fraud.” We, consumers, are made to want certain products that accelerate the commercial circulation, unconsciously connecting ourselves to the pool of knowledge that tells what is good. (Mills condemns the cultural apparatus as responsible for killing chance of the cultural workman to be a worthy craftsman).

If humans can contribute to create new and useful knowledge with faith in goodness, how? In the essay Image, Interpretation, and Interface, Johanna Drucker thoroughly reviews the history of the “humans” made a strenuous effort to put nonverbal communication - graphic design, visual representation, information graphics, and etc… - into the standardized language, so we can think and understand them throughout the universal frames. I imagine she had never thought that the language of the visual language already existed prior to the visual tools.

The author of Into the Meme Pool himself confesses that gene-meme analogy contains uneasiness because one belongs to tangibility and the other belongs to intangibility. Apart from that, I am still skeptic about the concept of looking at the human as a container of genes and memes. I have a friend who is a post-doc neuroscientist from Estonia. I happen to live with her now in Helsinki so I asked her “do you think the genes are the silent master of the human, enjoying its sake to copy themselves forever?”

Her answer was very clear: “genes belong to the material world that nobody owns “free will.” We, humans, have the spirit - free will- with which we choose the paths to better ourselves, based on the goodness we believe in”. She added, “I just want to think so.” I screamed, "me too!"

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading II: Design and Knowledge Nils Skogman, September 28, 2019

Of all the texts from this week's readings I found "INTO THE MEME POOL (you parasitize my brain)" to be the most interesting and thought provoking text, so most of this introduction text will discuss that text. This is also where I will start.

I have got to say that the concept of the meme is a very compelling one. The whole idea reminds me a lot of the subject of Kirby Ferguson's 2010-2012 video essay series "Everything is a remix" (it's a good one, I highly recommend it if it's new to you). The essay delves deep into what ideas are made of and especially how creativity actually works. It is presented there that all new ideas are entirely based on old ideas. They are formed either by modifying a single previous idea in some way or by combining several ideas into something new. Probably both. By this logic, no ideas can form in a vacuum. Everything you think about is dependent on previous knowledge and the only thing you can do with it is squish and squash or mix things up. If you're a creative person, it just means that your capacity of linking together unrelated ideas is a little better than average.

That being said, what if all of our ideas consist of memes? Here by the way, I think of ideas as collections of memes rather than memes themselves. To me it seems more like memes should be snippets of ideas that only contribute a part to it themselves, just as genes only code for single proteins but several genes working in tandem create more complex actions in a cell. Anyway, if all ideas consist of memes and those dictate your thoughts, then that's going to have some far reaching implications.

What does this mean for our identities, for instance? Are our minds a complete hodgepodge of memes and nothing else? Now I know that a lot of people, some psychologists and buddhist monks alike, will insist that you are not your thoughts. Just think about Mozart as mentioned in the text. His head is filled with thoughts and melodies spontaneiusly popping up in his mind. Where do they come from? What are they? And most importantly: are they any different than your own thoughts? I certainly don't believe so. Spontaneous thoughts are just as much yours as any other thinking is you. If you think about it, the origin of more deliberate thoughts is no less mysterious. Who's doing the thinking really? And what are you if not your thoughts? Are you just an agent, trying to react to some commands coming from somewhere else in your brain? Is consciousness just the ability to observe what the body would do anyways?

This line of thought quickly gets very deep (and off topic) very fast. There's a lot of people who have studied these sort of questions for their whole careers, so undoubtedly you can delve into the psychologies and philosophies of mind if you're interested in this sort of stuff. What I'm interested in however, is what this means for creative agency. As in... does it exist? Do you have any? Going back to Mozarts small thoughts before sleeping, isn't all the things you create really just a consequence of these spontaneous thoughtlets? Sure, you might carefully pick out the ones that you see most fit (and hence helping them to spread to other minds), but they must originate from the very same place, mustn't they? That would mean that the only thing we have in terms of creative agency is that of curating. It doesn't matter whether you skillfully paint something from your mind or choose the prettiest fractal generated by a computer. The only real difference is motor control. Because your thoughts aren't yours. They're just memes. From the memisphere. Or whatever they call it.

All this being said I don't mean to say there's necessarily bad about memes. Not at all. In fact, calling them parasites of the mind is a bit demeaning. A more proper term would be symbionts. We're in fact intimately dependent on each other, as much as the bacteria in our guts if not even more. A meme can't exist without a human and a human without memes is a human without thoughts. A human without thoughts is, in the "wild" at least, a dead human. We do indeed owe our complete success as a species to memes. All our most incredible feats, all our great cultures and cities, our whole civilizations, are monuments to memes. Bet you didn't think that the first time you heard the word, did you?

Turned out to be completely about memes this time. Oh well. Here's a link to the video essay btw: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nJPERZDfyWc

0 notes

Text

Introduction Reading II: Design and Knowledge Sabina Friman, September 28, 2019

What is knowledge and how do we produce it? The three texts, although rather different in style and focus, all offer insight on the topic of knowledge and ways of knowing. Johanna Drucker – author, visual theorist and cultural critic – discusses visual epistemology i.e. visual forms of knowledge production (Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production), while James Gleick – author and historian of science – offers a narration on the topic of memes as vehicles for spreading knowledge (The Information: Into the Meme Pool). The third text by Charles Wright Mills – social theorist and critic – focuses on the designer’s role in generating knowledge, and through that, arguably, even in shaping collective truths.

As Drucker extensively discusses the production of knowledge in the form of visual epistemology, she begins by explaining that many attempts at creating a stable, universal and rule-bound graphic language have already been made, as ”the systematic production of graphic knowledge has a very long tradition” – despite its disproportionately devalued position as a form of knowing throughout history and still today. Drucker outlines several different approaches to understanding visual epistemology systematically, and although not directly comparable to the defined boundaries of say, mathematical or grammatical knowledge, I’d agree with Drucker in seeing it as equally valuable – maybe even more so in contexts where for example language doesn’t suffice.

In her text Drucker also establishes the ”urgency of finding critical languages for the graphics that predominate in the networked environment” today. She ends the text by raising the contemporary question of whether design principles can be abstracted and made explicit enough for a machine to be taught what I would call the process of designing. I think this relates heavily to the topic of automation within design practice, and raises questions surrounding designer ”criteria”; how has technology and automation changed our profession so far? To what extent can design still be linked to design practice if a machine is involved? What will the relationship between designers and technology be in the future? Will there be a need for designers, as defined today, at all?

Throughout his text on memes, Gleick offers a vivid visual metaphor to concretize the abstract concept of spreading of a certain type of knowledge. He likens information and ideas with living matter, as they too evolve and spread through replication; or, in the context of ideas as memes, imitation. ”Plain mimicry is enough to replicate knowledge” Gleick states, but stresses that language ”supersedes mere imitation, spreading knowledge by abstraction and encoding”. I think this relates directly to the power in thinking about visual communication as a structured graphic language of its own, capable not only of spreading abstract and encoded knowledge, but also generating it.

However, thinking of this in relation to my own practice, the terms replication and mimicry evoke feelings of unease in regards to originality; where did I really get this idea from? I often find myself questioning the uniqueness of my work and taste, as I know I subject myself daily to e.g. visual styles and trends that spread like wildfire through Instagram, continue smouldering on Pinterest boards only to end up in my dusty digital folder named project inspiration. I think of these evolving ideas and circulating trends as the memes that Gleick on the one hand describes as intangible, yet on the other as complex units with effects on the world beyond themselves. He goes so far as to suggest that our human brains are merely hosts or vehicles for these infectious ideas – a surprisingly relatable thought, I think – and ends with questioning who is actually in control; us thriving on the information, or the information surviving through us?

Mills on the other hand, tackles the topic of knowledge from a distinctly designer-centred, almost instructive, point of view. He situates the designer (of the 1950’s) as a cultural workman trapped between the changing social forces of culture and economy, thus urging them to rediscover purpose and independence by critically examining the designer’s role within an increasingly capitalist society. I interpret his main reason for encouraging reflection on designers’ part to be the responsibility they possess in defining what he calls the cultural apparatus; ”As a member of the cultural apparatus, you surely must realize that whatever else you may be doing, you are also creating and shaping the cultural sensibilities of men and women, and indeed the very quality of their everyday lives”.

In a way, this process of cultural shaping is synonymous with that of creating knowledge, and through that constructing truths – the way we perceive something to be true, anyway. Mills argues that ”the only truths are the truths defined by the cultural apparatus” and writes that without the contribution of art, science and learning to this cultural apparatus, ”there would be no consciousness of any epoch”. This underlines the importance and responsbility of the designer as a central agent in all of this, which makes me think of my own practice in a different light. As individuals, I believe we all recognize the feeling of powerlessness; I often catch myself doubting what difference my work really makes in the grand scheme of things. Even Mills admits ”the enormous difficulty any designer now faces in trying to escape the trap” of essentially capitalist society. However, he provides a curious theory of craftmanship as pinnacle of the creative nature of work, reminding us of ”the central place of such work in human development as a whole”. I think it’s safe to say that realising and assuming our roles as designers integral to cultural change feels nothing less than empowering.

0 notes

Text

Introduction

Reading II: Design and Knowledge

Laura Kamppi, September 26, 2019

For this next meeting, I started by reading The Man in the middle chapter from the The Politics of Truth written by a sociologist C. Wright Mills in 1958. My first thoughts on this text was that it was quite heavy to read because of its themes. What I found interesting was that it was because of the heavy themes though that made the text still feel quite timeless in some parts. These themes for example about how the designers’ role is perceived to constitute to capitalism and how to deal with that notion as a designer, are so large-scale and need continuous questioning. For a designer these are the kind of inner questions about the impact of their work that they simply cannot help asking themselves.

In my opinion C. Wright Mills describes the feeling of being overwhelmed by your role as a designer quite well: “Designers problems are among the key problems of the overdeveloped society. It is their dual involvement in them that explains the big split among designers and their frequent guilt; the enriched muddle of ideas they variously profess and the insecurity they often feel about the practice of their craft; their often great disgust and their crippling frustration.”

Mills writes that no matter what, designer’s economic task is to sell. He continues by saying that designers become part of something much bigger, where they themselves don’t have power.

He wants you as designer to recognize this. He engourages designers to really try to understand what they are doing because naturally the things we produce reveals our values. According to Mills the problems of the designer can be solved only by radical consideration of fundamental values. “The designer is a creator and a critic of the physical frame of private and public life.”

In his text Mills is also pointing out how craftmanship is an important value to designers. I think that by this his is referring to the material knowledge that each designer might possess. For me at least, I notice that knowledge gained by a physical activity, such as printmaking or reading through a magazine, gives me confidence and a feeling of validation in a way to just keep doing what I do. Knowledge like this can be empowering to designers, but in what other ways to gain knowledge and put it into use?

A non-fiction writer James Gleick has an interesting way of looking the spreading of knowledge in the means of internet and biology in his Into the Meme pool chapter. It is interesting how he is comparing memes to genes, a point of view that I have never stumble upon before. According to Gleik ideas, tunes, catchphrases and images, all contain spreading power and a meme is basically a combination of these. A meme that first comes to my mind while reading is “the distracted boyfriend” meme.

youtube

James Gleick writes that ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins already compared evolution of genes and the evolution of ideas with each other. To depict this comparison, Dawkins says: “All life evolves by the differential survival of replicating entities.” A meme is something that for example is based on the function of replication, according to Dawkins.

Rhyme and rythm are qualities that aid a meme’s survival. The problematic thing about these self-replicating patterns of information, is that it gets more difficult to break out of this patterns. I think that in order to do this, we need designer’s to use their knowledge here; to bring visible the vast knowledge that is left outside of these patterns. After all, the whole internet is about people sharing knowledge, exchange of thoughts. A meme is something that can work here, it is the fastest way of expressing thoughts anyway, in a very spreadable form. Gleick is referring to Philosopher Daniel Dennett, who says a meme “is an information packet with attitude.” I think this is good quote, I cannot think about another as effective way of communicating in the internet emotion better than a meme. Another good quote from the text fitted here: “Ideas cause ideas and help evolve new ideas.”

Johanna Drucker’s text is about how our interpretation on images is linked to our knowledge of the world. A very interesting topic in my opinion, but also very complicated topic. It is good that we are having a discussion about this text in particular, because it is a lot to take in at one read.

The term epistemology was new to me. Drucker explains: “The field of visual epistemology draws on an alternative history of images produced primarily to serve as expressions of knowledge.” I thought the introduction the the chapter Image, Interpretation, and Interface, was clearly put, showing that there truly is a link between knowledge and visuality: “Since we inhabit a world permeated by digital technology, we will address the urgency of finding critical languages for the graphics that predominate in the networked environment: information graphics, interface, and other schematic formats, specifically in relation to humanistic problems of interpretation. To do this we can draw on the rich history of graphical forms of knowledge production.”

0 notes

Photo

Summary Reading I: Discourse and Authorship in Design Practice Nils Skogman, September 23, 2019

0 notes