Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

im so fucking determined to get better i swear to god lets do this bitch lets go

145K notes

·

View notes

Text

If I had a bf, I would stare at him. Like a LOT...

0 notes

Text

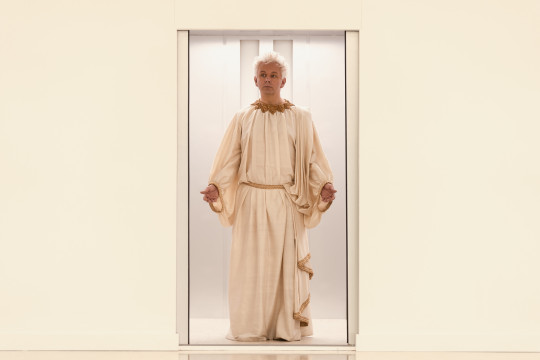

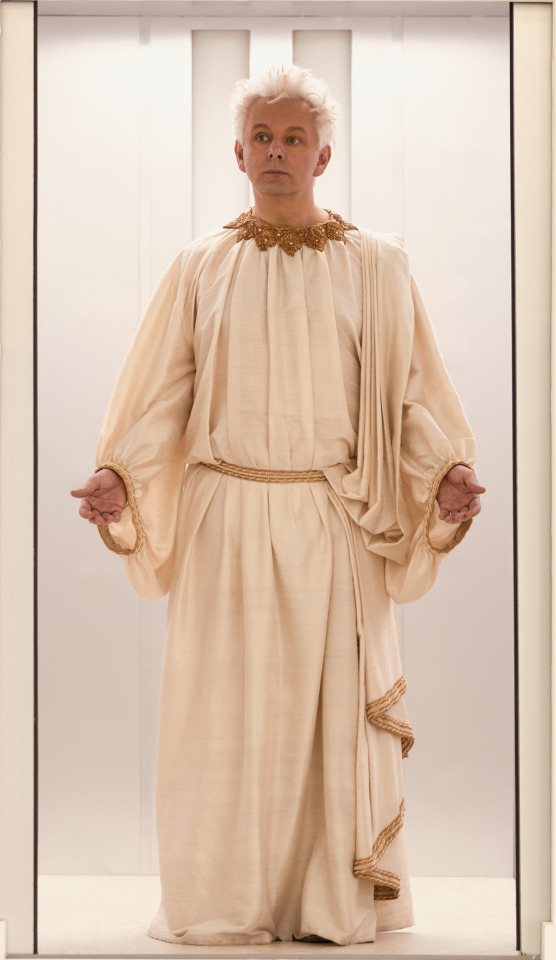

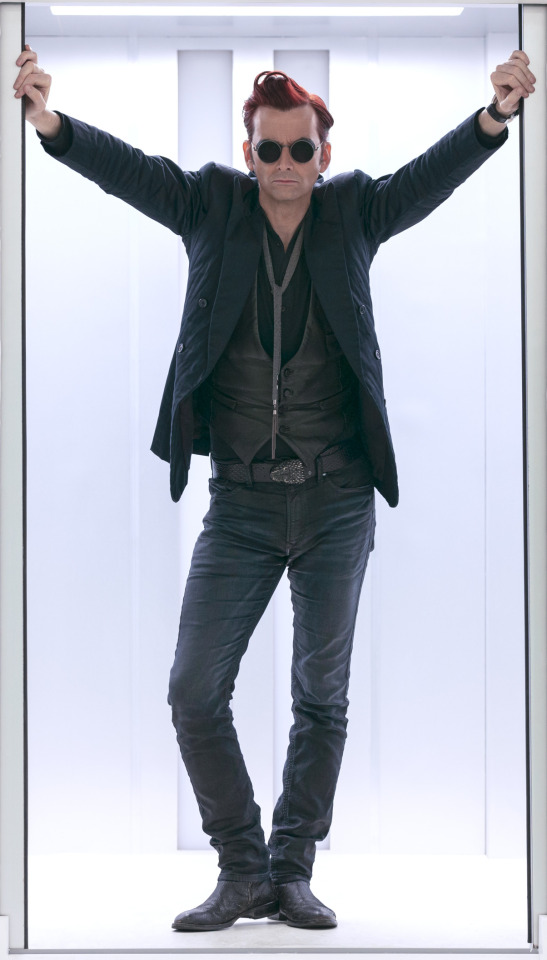

Can we really blame Aziraphale and probably half of Soho for falling in love with him?

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the best academic paper titles

117K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pt I good omens but i've never watched it

i've never seen good omens but it's all over my tumblr dash so this is what I've gathered can someone please confirm if i've got it right

there's a demon named crowley

there's a biblically inaccurate angel named aziraphale but like it's very sexy when the demon calls him 'angel'

the demon and angel have been married for 6000 years and they still keep looking at each other all sappily

Neil Gaiman is somehow involved, I think he's the writer but also he's on tumblr (uh, @neil-gaiman) and people keep questioning if he's real

is neil gaiman like a fandom inside joke why is everyone asking if he's real

there actors are called michael and david and amazon prime thought they were the same

there is a bookstore and crowley is sad

they kiss and it is very nice and desperate and crowley says we could have been us. i have no context for this. someone is going to heaven i think.

there is a god, i'm not sure if they're good or evil though

the demon wears sunglasses

it's a comedy but for some reason everyone's crying after whatever the last season was, are you guys okay

things are on fire

they are very gay

there was a book and at one point they switch bodies

more fire and crowley screaming

they are called ineffable husbands i dont know what that means

they fight crime or they do crime or they fight crime by doing crime i really cannot remember which

gay

9K notes

·

View notes

Note

The most important question about s3, is David Tennant going to be set on fire?

If Amazon decide not to commission Season 3, I will personally set David on fire to make up for it.

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it would be better for everyone if I were to be left alone in the future. Don't you?

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

More than Meets the Eye: New Research Shows How the Visual System Contributes to Memory

When we use our working memory, we temporarily retain information in our brain. For instance, you are able to comprehend this sentence because you are briefly storing in working memory each of the words you are reading until you put them together to form the meaning of the sentence. The importance of working memory to many of our cognitive abilities is well known, but less clear are the neurological machinations driving this process.

A team of researchers has now demonstrated that the key to understanding working memory relies not only on what one is storing in memory, but also why. This is the “working” part of working memory, which emphasizes the purpose of storing something in the first place.

“We now know that our visual memories are not simply what one has just seen, but, instead, are the result of the neural codes dynamically evolving to incorporate how you intend to use that information in the future,” explains Clayton Curtis, a professor of psychology and neural science at New York University and the senior author of the paper, which appears in the journal Current Biology.

Specifically, the study focuses on both how we store the visual properties of our memories in the occipital lobe, where our visual system resides, and on how the neural codes that store those memories change over time as people begin to prepare a response that depends on the memory. In the Current Biology study, the response simply required people to look where they remembered an object that disappeared several seconds ago.

“The research makes it clear that memory codes can simultaneously contain information about what we remember seeing and about the future behavior that depends on those visual memories,” notes Hsin-Hung Li, an NYU postdoctoral researcher and the paper’s lead author. “This means the neural dynamics driving our working memory result from reformatting memories into forms that are closer to later behaviors that rely on visual memories.”

Textbook theories state that the storage codes for our working memory are stable over time. This means that the pattern of neural activity that stores a given visual memory is the same as when it was first seen and encoded—whether it is a second later or 10 seconds later. These patterns of neural activity store visual memories, providing a bridge across time between a past stimulus and a future memory guided response.

However, recent studies of animals indicate that these neural patterns are much more dynamic—in fact, the memory codes are not stable and, instead, appear to change over time in puzzling ways.

To explore this, Li and Curtis, who previously uncovered how our working memory is formatted in the brain, devised innovative methods to both measure changing neural dynamics and critically make the dynamics interpretable. To do so, they projected the complex neural measurements into a simple 2D plane, like the screen of your laptop or smartphone.

The video below depicts how the pattern of neural activity evolves during a working memory trial. Initially, you can see a bump of activity encoding the briefly presented visual target (pink circle) in both primary visual cortex (V1) and a high-level visual area (V3AB). In V3AB, this bump remains at the target location throughout the memory delay. However in V1, a line of activity evolves during the delay between where the person is looking (pink cross) and where they will move their eyes after the delay.

The researchers believe that this line reflects the trajectory of the shift of gaze that is being rehearsed in people's minds, but has yet to be executed.

Although previous work had documented neural dynamics during working memory, the reason for why these dynamics occur had remained unknown. These new results help address this mystery. They indicate that the dynamics reflect transformations of past sensory events— what we have just seen—into future memory guided behaviors—what we might do with the memory.

“We’ve now shown that mnemonic codes can simultaneously contain information about a past remembered stimulus and the subsequent behavior that depends on that stimulus,” observes Curtis. “The neural dynamics of our working memory result from reformatting memories in order to align them with how we use them in the future.”

28 notes

·

View notes