Have you ever been watching Fargo and thought, "Wow, this really reminds me of Kant’s Categorical Imperative" ? Or maybe you were watching Breathless and thought, "Wow, how very Sartrean!" If you've done this, you probably i) have a tendency to overthink things ii) were kicked out of your university's film club for ruining everything, and iii) will really enjoy this blog. Bring your frameworks, bring your imagination, bring your popcorn. Welcome to a ___ viewing of ___.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

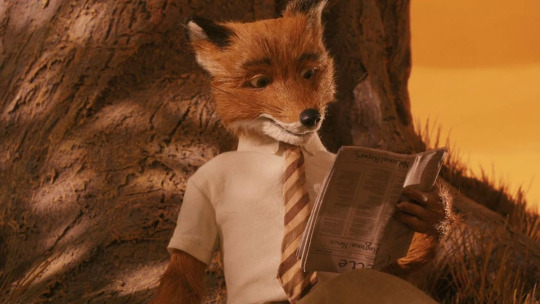

An Aristotelian Viewing of Fantastic Mr. Fox

The worlds of Wes Anderson rarely follow the rules. Not only are they aesthetically pristine in a way the real world could never be, but they also suspend the humdrum regularities of everyday life in a way that can only be called—fantastical. The world that Anderson creates in Fantastic Mr. Fox, however, takes things to a whole new level. We’re not talking the unlikelihood that a high school would consent to Max Fischer’s ridiculous amount of onstage pyrotechnics. We’re not talking a Khaki Scout tree house built to a staggeringly unsafe altitude. Hell, we’re far beyond Zissou having a full sauna complete with Swedish masseuses aboard the Belafonte. The fact is, all of those things are highly unlikely, but they’re still physically possible. In Fantastic Mr. Fox, we’re straight up breaking the laws of nature, baby. Animals exist as humans do; they speak English, wear clothing, and carry out their lives in communities fixed with schools, real-estate agencies, and grocery stores. If it wasn’t enough that animals live as sentient, rational creatures, they also coexist with human beings. Wait, what? That’s right, and, despite acknowledging their weird, anthropomorphic neighbors, human beings still consider animals to be lesser creatures. The impetus of Mr. Fox’s existential crisis (maybe we could even call it a mid-life crisis? I don’t know how long foxes live) is starting to come to the fore. Mr. Fox’s crisis results from the realization that he must continue to function both as a wild animal and as a rational creature. Still not a human, though. Just a fox wearing a tie.

For all intents and purposes, Mr. Fox truly is a rational, wild animal. If you’re an Aristotelian, you’re probably shitting yourself right now. Don’t panic! We’re going to examine this “rational, wild animal” under an Aristotelian lens and see what the hell is going on inside Mr. Fox’s head. Plus, once we understand how Mr. Fox fits into an Aristotelian framework, perhaps then we can answer another question: what would Aristotle say about Mr. Fox’s decision to do his “last big job?”

For Aristotle, every substance is made up of both matter and form, form being the physical arrangement of the thing and matter being the substratum that makes up the form. (Physics, 190b10-191b10) For each substance (individual), the soul is the form of the body, and the body is the matter. Thus, the form of a substance is much more than just what it looks like, much more than just the shape of a thing. In the De Anima, the soul is indeed described as more of a life force that all living things possess. (De anima, 412a7-15) Aristotle believes that the soul follows a hierarchy of functions from plants to humans, with humans possessing each prior function. The hierarchy is separated into three degrees: nutritive, sensitive, and rational. A nutritive soul is the soul’s ability to simply sustain its body, a sensitive soul sustains but also moves and perceives, and lastly a rational soul is one with the ability to use reason. Human beings are the only creatures that possess all these qualities (De anima, 414a28-414b1).

Now, the fundamental problem lies in trying to pin down Mr. Fox’s essence. According to Aristotle, an essence is what makes a being what it is or, as Aristotle phrases it, the “whatness” of a thing. (Metaphysics, 1029b) In other words, it is that characteristic of a being without which it would cease to be that type of being and which differentiates it from other types of beings. For example, the essence of man is his capacity to reason, which distinguishes him from other animals. Hence, the famous definition of man as the “rational animal.” Now, how do we come to know the essence of a being? Well, the type of soul a certain being has makes it so that being is equipped with certain powers for action. Thus, the essence of a being is instantiated by its nature, that is to say, its natural dispositions for action. You can think of an animal’s essence as being evident in its “work.” For example, we see a beaver’s essence in its natural disposition for building dams. Recall now the opening scene of Mr. Fox, when Felicity and Mr. Fox are caught in a fox trap, Felicity tells Mr. Fox that she wants him to find a “new line of work,” an impossible request of a wild animal, since an animal’s “work” is what qualifies and characterizes it. To find a “new line of work” for Mr. Fox would be to undergo what Aristotle calls a substantial change i.e to change his very essence so that he is no longer a fox. (Physics i 7, 190a13–191a22). This search for who he is and what it means to be alive is what prompts his questioning of the role he plays in nature as a rational animal. This should be your “oh shit” moment. Mr. Fox is definitely rational. He’s also definitely an animal. By definition, it seems like Mr. Fox is…human? But he’s also a fox? My brain hurts?

Now, for human beings, our purpose in life is to achieve excellence through the habituation of virtuous actions, which we are able to do through our power to reason. (Nicomachean Ethics i 7, 1097b22–1098a20; cf. De Anima ii 1, 412a6–22) This is tied to Aristotle’s teleological view of nature, that is to say that everything has a natural “end,” or “final cause” to which its life is directed. So, we see Mr. Fox’s crisis is even more serious than we thought. Because he can’t figure out who or what he is, he doesn’t know his purpose in life, his final cause.

To be honest, I’m not sure why it’s just Mr. Fox who’s having an existential crisis. All of those animals should be freaking the hell out. All the animals in Fantastic Mr. Fox seem to be aware of their own, individual natures. For instance, when the Fox family considers moving from their hole to a new home inside of a tree, Mrs. Fox remarks, “have you ever considered that foxes live in holes for a reason?” Or, when the farmers strike and all the animals find themselves fleeing underground, Phil the mole exclaims, “I just want to see…a little sunshine.” To this, Mr. Fox replies, “But you’re nocturnal Phil, your eyes barely open on a good day.” It is evident that each animal recognizes that they are a different species with different characteristics and strengths. However, there seems to be a base ignorance of the fact that these animals would not normally interact with each other in nature, and this proves to be a problem at certain points of Mr. Fox’s mid-life crisis. For example, Mr. Fox employs Kiley the opossum as his second in command when deciding to steal chickens from Boggis, but he realizes too late that, unlike himself, Kiley is not equipped with the proper teeth to kill a chicken with one bite. Wait a second, though. Kiley and Mr. Fox are bros! They’re equals, even! They’re both rational creatures! Yet, their essences seem to be entirely different. Mr. Fox is torn between this strange dichotomy: all the animals are fundamentally different, yet all posses the same intellect. No wonder Mr. Fox is struggling! Not only is he supposed to feel guilty for acting on his instinctual fox urges, but all of his friends and neighbors are also different species from him! They’re all essentially different and yet essentially the same! To make matters worse, they’re all essentially the same as humans, yet somehow inferior?? Eugenics, much?? To put it simply, Mr. Fox has no idea where he (or anyone for the matter) fits into Aristotle’s grand chain of being.

Mr. Fox is fighting an internal battle between two fundamentally different essences. On the one hand, he has an instinctual, animalistic fox essence that’s making him want to do hoodrat stuff like steal chickens, and on the other is his rational essence, which clues him into the fact that stealing chickens is irrational because it jeopardizes the safety of his family. Aha! So, not only is Mr. Fox a rational creature, but also an ethical one. You see, Aristotle describes a voluntary action as an action that can be rationalized as good or bad by the agent of the action. (Ethics, 1105a31-36; 1105b1-4) For an ordinary fox, stealing chickens would not be immoral at all, since they need to steal to survive. Plus, foxes don’t even have a concept of right or wrong to begin with, so they’re not culpable for their actions. Mr. Fox, on the other hand, can survive without stealing chickens. Remember, they have grocery stores. With juice boxes and dancing. Further, Mr. Fox definitely has the ability to distinguish right from wrong. Mr. Fox is therefore left wondering why he’s even a fox at all if he’s not supposed to do what foxes were born to do. He says, “Why a fox? Why not a horse, a beetle, or a bald eagle? I am saying this more as like existentialism, you know? Who am I? And how can a fox ever by happy without a—ahh, you’ll forgive the expression—a chicken in its teeth?” So, it seems like the “last big job,” is selfish on Mr. Fox’s part, as the price to pay for his desire to be “fantastic” is the deception of his family and his dragging them into his dangerous schemes. On the other hand, it is equally selfish of Mrs. Fox to demand that he reject his natural tendencies.

At the heart of it, because Mr. Fox is a rational creature with the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, Aristotle would argue that he must be thought of in human-like terms. After all, Aristotle describes virtue as something purely human: “But clearly the virtue we must study is human virtue; for the good we were seeking was human good and the happiness human happiness. By human virtue we mean not that of the body but that of the soul; and happiness also we call an activity of soul.” (Ethics, 1102a13-16) This further proves that Mr. Fox must be thought of as a human in every respect except for the wild animal instinct that he suppresses. Mr. Fox should be held morally responsible for his actions because he has the ability to realize that the wellbeing of his family is more important than his animalistic urges. To put it simply, in pulling his last big job, Mr. Fox is being a reckless dick. In fact, after everything has gone to shit, when Mr. Fox has screwed everybody, and all of the animals are hiding out underground, Mrs. Fox pulls Mr. Fox aside and asks, “why did you lie to me?” Mr. Fox replies, “because I’m a wild animal.” No, Mr. Fox, you are a rational animal, and also a bad role model for your son. By the way, just because he’s little and not very good at fox things and sometimes wears tube socks on his head doesn’t mean he isn’t fantastic, either!

So, is there hope for Mr. Fox? Well, we gotta talk about the wolf. Mr. Fox remarks several times throughout the film that he has a phobia of wolves, not a fear of wolves, but a phobia. This motif serves two points, the first being that Mr. Fox is aware of the fact that wolves are a natural predator of foxes, and thus acknowledges that animals have a different mode of existence than humans, a different spot on the food chain. Secondly, the wolf is a metaphor for the wild part of Mr. Fox’s being, the part of him that cannot be tamed or gentrified. Just before the climax of the film, as Mr. Fox, Ash, and Kiley ride away on Mr. Fox’s motorcycle, they spot a lone wolf in the distance. Unlike every other animal in the film, the wolf is undressed, walks on four legs, and does not seem to speak English (or Latin). Mr. Fox and the wolf share a silent, yet understood moment. They both raise their paws in the air, and Mr. Fox leaves with a newfound respect for the creature he once feared. This encounter symbolizes Mr. Fox’s acceptance of his wild side, and his decision to renounce it to embrace his life as a civilized husband and father.

At the end of the film, Mr. Fox has come to terms with his existence and the role he must play in the lives of his family members and the members of his community. He realizes that he can still be fantastic by just being himself, and can still be a “wild” animal without hurting his family. If he can’t steal chickens from Boggis, geese from Bunce, or cider from Bean, stealing from their grocery store is an ironically civilized, and perhaps even a noble compromise. Sort of like when you quit smoking because it’s killing you, so you take up vaping instead? It’s sort of the same, and maybe it suppresses your urges for awhile, but it will never compare to a fresh, smooth American Spirit (yellow pack, ofc). But, that’s the price we pay to be responsible human beings. Or responsible foxes, I guess.

So, what did we decide? Mr. Fox is a human. Stealing is bad. The world of Fantastic Mr. Fox is fucked up.

Thanks for reading. Submit requests for future ___ viewings of ____ !

* I should say that this is a painfully truncated summary of Aristotelian philosophy and I wanted to touch on so many more things. But alas, at the risk of this being *too* long, I stuck to some very, very basic Aristotelian stuff. We can touch on some deeper stuff in future viewings.

9 notes

·

View notes