Writings, thoughts, funny stories, reflections, and more from the School Meeting Members of Arts & Ideas Sudbury School. Learn more at aisudbury.org

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

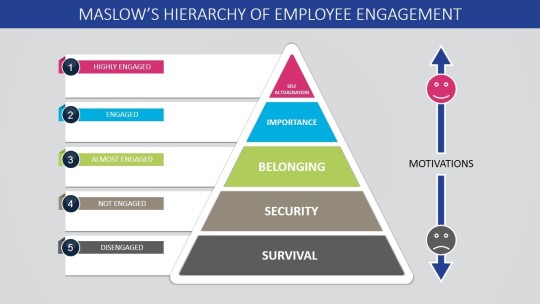

Maslow's Hierarchy and Sudbury Schools

I recently read a blog post that had the following depiction of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in it:

This was a post on Universal Basic Income, but I felt like I could apply this version of the hierarchy to Sudbury Schools, something which has been discussed before at Philly Free School.

The idea is to view the school through the lens of this hierarchy. We will start with the security level as survival is something that is handled by parents.

Security

At Arts & Ideas, we pride ourselves that our students feel safe. Instead of a theater of security, we have actual security.

It is hard to observe this directly, but our community is watching out for all of its members. There is an attitude of not ignoring problems nor making them worse. Our students do push their own boundaries, but in ways that lead to scrapes and bruises if failure happens. They also push at the boundaries of our community, but our JC system pushes back before the lines get too far crossed.

The role of staff is to be the adults that can be counted on to take care of an extreme situation. Our attitude of not using an incident as an excuse is crucial to our being called in when our help is needed. If there is a problem, we are notified and we deal with it. We are not defensive nor sermony. This allows us to build the trust that provides this deep level of security.

Our students feel safe in their time here.

Belonging

The lack of labeling students, judging of individuals, or expecting certain outcomes gives a strong sense of emotional security to our students which very much is about belonging to the community.

With the adults showing acceptance of all students, other students also naturally accept others. They may not be friends and may even have minor squabbles, but the basic fact of existing as a member of this community is unquestioned as long as the boundaries of the school are respected.

Even when we have the occasional student that repeatedly or dangerously crosses our democratically established rules, the community does what it can to help the student stay with us and respect the rules. Our expulsion process requires at least 75% of the community to agree to expel. When we have taken such a vote, it is a solemn act, one that helps all of us reflect on how much we value our fellow community members. Even the loss of students who have been with us for a short, disruptive time are still remembered with acceptance tinged with a feeling of sad loss.

Arts & Ideas provides a space for our students to just be. In a world of commanding and demanding adults, it is one of the few places where they can feel they belong. It is why the staff do their best to work with the chaos of children in the office. Sometimes we have to quiet them to talk on a phone call or some other such need, but we do our best to respect that the office is just as much a place for students to be as it is for staff to be.

This school is their place. They belong to it. They have a community that does care for its members. We may or may not be friends, but we are a group.

Importance

We value students as they are now for what they bring to our community.

It is worth pausing and letting that sink in as a contrast to how children are often viewed. Far too often, adults are thinking about how a child can be valuable when the child grows up. Conventional schools are based on the subtext that children are not valuable now, but we can make them valuable in the future.

We say no to this idea. Our students do grow up to be valuable members of society, but it happens because we value them right now. Being valued is a natural human craving, for the young as well as the old.

If we reflect on what often irritates us in our adult interactions, it can often be viewed through the lens of not feeling valued. The same is true for children, but it can be even more important since they might never have felt valued. Rather they may have always felt that they were a burden on those who cared for them. It is, in one word, tragic.

We see a fire for life in our students and that fire runs our community. Every single one of our students contributes to our community.

At a basic level, we have the formal participation. We have Chore Teams, Judicial Committee Teams, and School Meeting Teams which all of our students participate in. One of the great joys I have as Law Clerk is to pencil in a new student into the teams. I know that they will get the message that they are valued.

Their service is needed by the community and valued. For new students, this can be a startling statement that their opinions actually do matter. We have seen many a new student voice opinions and participate in voting on the teams. We do have a rule that allows their first term of service on JC to be done without having to vote. This was done so that they can embrace the offer from the community to contribute. Within a day or two, students start voting and I know from my own experience how warming that welcoming of one’s voice can be.

But our community receives far more than formal service to the community. Each student is contributing to our community in their interactions with each other. The whiteboard drawings that are scattered around the school, the left out creations, the kinetic energies, the conversations and jokes that abound, all of these are valued. We have an ocean of social experiences with various currents, eddies, and pools leading to adventures around every corner.

I should hasten to add that we do have students that often largely keep to themselves. It may not be apparent to many, but they are deeply valuable to us as well. These students give permission to all through their quiet example that being quiet is okay. There is a quiet serenity that surrounds them which I think awes some of our more vocal students. It is something wonderful that our community will value the quiet and the loud. We do not all have to speak up all the time. And when a quiet person does speak up, we all listen.

This can be quite literal, by the way. One of our JC Clerks speaks rather quietly and the JC Room becomes still as every member of the room listens with deep intensity to the words of the clerk. Far from being a detriment, the quietness of the clerk promotes a sort of unity in the room. Our louder clerks can engender raucous debate. Both lead our community in just directions and both ways are valued.

Self-Actualization

Confidence is what comes to my mind when I think of the most common trait across our long time students. Confidence is what one gains when truly being valued by others becomes internalized.

Arrogance is what an A+ gets a person, the belief that knowledge has made them valuable. It is shallow because it is not valuing the person, but rather valuing some trick that they have assimilated.

Our community’s value of the person is not from them being able to demonstrate some skill, but rather valuing them for who they really are. It is the difference between paying for a friend and having an actual friend.

To be sure, our students have doubts about their future and about what they may be missing from conventional schools. This comes from the lack of being valued outside of our community. While we can tell stories of the many successes of Sudbury students, including our own, our options are limited in what we can do except to help support our own larger community in embracing our students for who they are, right now.

This is why it is important to let go of being concerned about whether the children will read or can do math or whatever it is. If we worry about this, then we are giving the message that they are not valued for who they are without that skill. Survival, security, acceptance, and importance, they all work together to lead to the moment of someone truly valuing themselves. And once that happens, anything is possible.

Indeed, even when I see doubts in our students, I still see below the doubts a deep reservoir of confidence. The doubt is superficial, the confidence is deep. The longer they stay with us, the more true this becomes.

A successful future is all about confidence. None of us are fully prepared for what we will need to do, but those of us that are confident that we can figure it out generally do. Those who have that, such as our students, are the ones that will succeed in acquiring the skills and resources needed to accomplish any of their goals.

Humans adapt to the expectations of their environment. For Arts & Ideas, we just assume that our School Meeting Members will be valuable to our community. We are not judging them, simply acknowledging the reality of the present with the expectation that the future will continue in the same fashion. And thus it is so.

0 notes

Text

Not Just Joking

by Phil Glaser (Staff at Arts & Ideas)

Sometimes, in School Meeting, we get into the weeds with joke rules. One frequently recurring prank that we deal with is the proposal to create a ‘No Breaking Rules’ rule. Usually the motion doesn’t receive a second, so we don’t get into discussing it, but sometimes it does. When this happens, the conversation goes around and around until its humor is outweighed by a general desire in the room to get on with the day, at which point someone interrupts the discussion with a motion to take a vote. The ‘No Breaking Rules’ rule has never passed, but that doesn’t mean we are without our joke rules on the books.

One such rule was discussed In School Meeting today. A motion to delete the ‘Shut Up’ rule provoked a sometimes earnest, sometimes in-jest, but always self-conscious discussion. The ‘Shut Up’ rule states that “Eating chicken in the chicken coop is prohibited.”

“I like this rule because it’s actually a good idea,” opined one School Meeting Member. “We wouldn’t want to allow people to eat chicken in the chicken coop -- it’s just ethically and morally disturbing.”

This reasoning appeared to create an invisible shockwave that propagated across the room and up the leg of a particular student, culminating in a massive eye roll, presumably to dampen the impact of such an absurd statement. The wave continued upward, forcing his hand to launch into the air, and bounced down and back up his body as he waited to be called on by the School Meeting Clerk. His squirming impatience was finally uncorked in its turn, unleashing a verbal torrent of the kind that only teenagers are capable of producing: “We’ve got other rules that cover this! The ‘Shut Up’ rule wouldn’t even prevent people from eating chicken right OUTSIDE the chicken coop. What if I stood inside the chicken coop with my head outside the door eating KFC! Would I be breaking the rule?! The rule doesn’t even cover the spirit of itself. It’s just pointless!...” The student then trailed off in a flustered string of self-interrupting beginnings of sentences, through which he managed to communicate his bewilderment. Despite his and his fellows’ apparent dismay, the defenders of the ‘Shut Up’ rule remained steadfast and, to the chagrin of the joke rule detractors, it was saved from deletion.

Throughout the debate, more-or-less uninvested onlookers chuckled at claims that if the ‘Shut Up’ rule was deleted, then it would throw the entire school - perhaps the entire nation - into chaos. There were prophetic proclamations that if it were deleted, people would spend all their time sitting in their chicken coops eating chickens (chickens who the eaters presumably knew less well than the coops’ residents bearing horrifying witness to the barbarity) and that this would continue straight through to the complete destruction of human society. An otherwise rational and calm populace would be transformed into a bloodthirsty mass whose only peace could be found in the consumption of chicken parts in chicken coops. Essentially, we’d all turn into zombies.

This conversation (like all joke rule conversations) was self-consciously ridiculous, a fact that amused some and bothered others. For the joke rule revelers the opportunity served as a powerful reminder of one’s own agency. Being part of an institution where anyone can talk about whatever they want with their hands on the levers of power is a liberatory state of being that most people don’t get to experience. Being able to see one’s own nonsense being taken seriously, along with the tiresome nature of such circular conversations, culminates in a tempering of the chaotic urge. Joke rules also establish their proponents as characters in the school community. This is apparent to most and, as a result, most joke rules are naked attempts to stamp a personal mark on the school. Having one’s name invoked explicitly (like bill sponsors in the US legislature) or implicitly is a sure way to enter the institutional memory of the school. The ‘Shut Up’ rule, though without a student’s name explicitly attached, is similarly a rule that provokes the telling of personal legends surrounding the student who was responsible for its introduction.

On the other, more earnest side of the ‘Shut Up’ rule debate is an exercise in patience and perspective. Such conversations about joke rules present themselves as ripe opportunities to put things right in a cosmic sense, however, here students find that things don’t always go the way of the rational. Guided by faith in the common sense of individuals, their desire (whether conscious or not) to strip down the rules to the bare necessities is subverted in a baffling way. They find that the decision-making ability of the peers that they choose to put stock in is not a product of unfettered logic. For these students, the seemingly senseless upset of their expectations is an opportunity to integrate the ridiculous into their understanding of what good-natured human beings are: creatively silly. Eventually, their boiling-over subsides into damp frustration, which, after some time, transforms ultimately into a level-headed tolerance for discomfort; a moment of zen.

Despite the ferocity of this particular debate, it should be noted that students are not simply on one side or the other of the joke rule conversation in general. Here, as in most places, context is king. After the ‘Shut Up’ rule’s place in the lawbook was secured once again and School Meeting was adjourned, some students stuck around in the room to continue the debate informally. Another student who hadn’t yet chimed in suggested to our aforementioned frustrated detractor that he should just try to delete another joke rule that people care less about. “What about, like, that underworld rule?” she offered.

“‘Ariel, Queen of the Sudbury Underworld’ is an iconic rule for the school! We can’t delete that one!”

0 notes

Text

The Hardest Part

I have a confession to make. The job of a staff member is hard.

Our job is great in many ways. We get to be surrounded by students of all ages doing fun and crazy things. We get to plunge toilets, replace fixtures, work with agencies and businesses of all kinds, write emails, formulate policies, mop floors, talk with parents, debate rules, argue different philosophies, witness conflicts with resolutions, pick up messes, be a shoulder to cry on, and do pretty much anything that needs doing.

It takes every bit of physical, mental, and spiritual energy we have to make it through a day. But using up all that energy in pursuit of maintaining a community brimming with life is about as satisfying a day as I can imagine. I am thankful each day for the opportunity to come home exhausted with a smile on my face.

But there is one part of the job that cuts my heart every time. Tears well up in my eyes just writing about it. It is the pain of losing students.

Often the circumstances of a departing student are bathed in a certain triumphant glow. The student leaves with their head held high, empowered to be present in the world and make it their own.

But it hurts to lose a member of our community. We all develop deep bonds with one another. To lose that bond is to lose a part of oneself. This is the price we pay for being a part of a community. New bonds are formed as new students join, but each student is too unique to replace. We have gaps in our heart for every missing member of our community.

Graduation

Some of our students leave because they are about to enter the adult world. Graduation is the word that comes to mind though that is but one option. Fundamentally, the call to be a useful part of the community at large calls to our older students. As the call rings, they rise to the occasion, emboldened with the support of the community that has loved and cherished them during their time here at A&I. They have been free and independent while being of service to, and respectful of, others. This is the gift that they take to the world at large. I would never dream to stand in the way of that.

Yet we miss them deeply and it is a bittersweet pain that fuels our new growth into new relationships.

Moving

Some students have family situations, such as having to move due to a new job, that take our students out of our community before their time. This hurts as well. We are comforted in knowing that our community will stay with them as they make a new life with new challenges. Even at a young age, the students who have been at A&I will emerge with a strength and vitality unmatched by those who have trundled along at conventional schools.

We miss them deeply and wish they could stay. But a new day dawns as new students move into our community.

Forced

There are other students whose family situations do not demand they leave, but the parents do. This cuts us deeply. It is rare, often a student or two a year, but it leaves deep scars. Parents have different reasons for pulling students, such as fear at being so unconventional or not being happy with the choices their child has made. In the past, these parents have failed to understand that basic idea of A&I: our students are human beings with their own lives that are theirs to claim and live.

We have deep conversations with such parents. They receive our words. They nod and maybe even cry. Sometimes they white knuckle their way through the period of doubt, but, occasionally, we fail. The parents decide to leave the school while the student wants to stay.

The scars from such pullings run deep in us. It hurts all of us in the community, but it falls hardest on their friends and the staff. We are crushed by the idea of someone ripped from a community that loves them and thrust into a world in which adults tell them what to do. These students were empowered, tasting what freedom and responsibility feel like, only to have it all taken from them and cast down into serving at the “educational” whims of others.

I see the picture on the wall of the student and I feel my heart just wants to stop. I loved them and failed to help them in their moment of need. I can’t even read the screen right now as my eyes tear up. Listening to Bob Seger singing “Why don’t you stay?” is not helping.

Sometimes I feel like Rock Biter from Neverending Story though I am comforted by knowing that, in the end, even these students will rise up, empowered by our community to make it through whatever trials they must face.

Sports

Other students are not quite ready to enter the full adult world, but leave to pursue passions that we do not have resources to meet. Sports is a big one for that. Students are willing to accept the loss of some of their freedom in order to play a sport that they can only play at a larger school. In many ways, it feels similar to graduates though it hurts a bit more as we know that we could have had more time with our friend.

We miss them, comforted in the knowledge that they are pursuing their dreams and passions elsewhere. But just as they leave for their passions, we welcome the new students who are joining us to pursue their passions at A&I.

Academics

There are students who leave us sometimes to pursue academics at other schools. We struggle with this. We know that anyone can learn academics at A&I if they choose to do so. There are plenty of resources in various forms, including us very capable staff.

I know from my experience in math education that individualizing learning is far more effective than traditional methods. Lecturing at a class, in real time, is very ineffective though I admit that, as a lecturer, I am not that inspiring. At the very least, we can all agree it is very hard to stay focused on a rapid fire of information coming at us for over an hour or two.

While that is true, there is something about a community of like-minded learners that can be very helpful. If a student finds a school where others want to learn and debate and fuel the inspiration to pursue a subject matter further, then this can be a good option. We certainly do not have many students exploring history, literature, mathematics, or science though we do see some students pursuing such subjects. But it certainly can be hard to form working circles on any subject. Even restricting to a single subject, such as history, there are so many places to investigate and explore that it can be overwhelming.

Most conventional schools do not do anything even remotely close to fostering the independent spirit needed for effective learning of any of the subjects. One place that one expects this to happen is college. But students who are somewhat interested in this knowledge at a younger age do not easily have access to this option. And, of course, even at college, many college students are more interested in their sudden freedom than the academic subjects that they have been forced to read.

Departing for academic pursuits is also often for those with just a slight desire for it. They do not have that deep thirst for knowledge that can fuel the individual initiative. Those with a thirst need nothing more than what they get at A&I and would find most conventional schools to be an impediment.

So this is an issue where we feel sad and uncertain about how to proceed. Generally, students leaving for such reasons are making the choice themselves, albeit with likely pressures from family, external friends, or the culture at large. They feel empowered and ready to take the challenge. We know that they will excel. We know that they will face any oppression of individuality with the calm force of resistance that any truly centered individual would display in such circumstances.

But we also know that they could have stayed and prepared better for what lies ahead by staying with us. We miss them deeply and yearn for the alternative path that would have let them stay with us. And yet we also know that just as they leave for academic pursuits, we will have others that are attracted to A&I for the freedom to pursue the depths of an academic subject that lights their passions. Mastery of a topic requires plenty of time and space for explorations, failures, and playing with ideas. It is incredibly hard to get that anywhere else other than the unique opportunity that A&I offers.

Struggles

There is a final group of students that leave us that always leaves us asking what we could have done to convince the students to stay. These are students that choose to leave, but not in an empowered way.

It is legendary that when students come into A&I, they often have a “detox” period. My rule of thumb is that it takes about a month per year of oppression. It takes longer if that oppression continues in some fashion elsewhere.

Most of the time, students do make it past their “detox” period using the painful memory of why they left their previous place of being to power through the emotional releasing of that pain. Healing can often be harder than the original injury, but the end state is worth it.

As the years go by, however, the pain of that memory fades. They have embraced their lives, enjoyed their time, but then something new and challenging arises from within. This often happens in the early teen years, but it could happen anytime. Basically, some internal process happens that puts them on a different path. All of a sudden, their usual amusements no longer amuse them. They need to find a new path.

This can be very disorienting and painful. Boredom is often reported. There are the breakings of long term friendships as old friends suddenly seem silly or have otherwise grown apart. It gets harder to come to school.

Parents see the distress of their child. If they have a good relationship with their child, then the parent may take on the brunt of the complaining and really start to worry if A&I is the right fit anymore. Regardless, the student often takes this seemingly aimless wandering as a signal to find a new place to be.

It is easy to think that leaving the place one is in will resolve the problem. But wherever we go, we bring our problems. The problems inside any of us are just that: inside of us. We cannot escape by running away. We have to listen to our emotions and feed off them to grow beyond where we are.

It is the calling of the human heart. Boredom in this day and age seems like a dreadful disease, but it is the process of letting a person lie fallow as the next step emerges. Humans do not have literal cocoons, but we do have emotional ones. It happens throughout our lives, but it is at an excruciating stage in the teen years as one transitions from the child to the adult. It burns hot sometimes, but it burns cold far more often.

So some of our students think about leaving and parents who have accepted their child’s self-direction in life, support them. They might be secretly happy about it, but I think most are genuinely trying to be supportive of a scary step into a new direction in life.

And it is hard for us to argue with it. Maybe for some it is the right decision. But we as staff believe that in most cases, students need to work through these hard issues. Not running away from freedom is the toughest choice for them to make, but it will be the most rewarding.

There is something quintessential about being human that demands we accept our environment and craft it to our needs. Admittedly, some environments even escape our industrious natures to make useful, but that is a rarity. For the most part, students who feel that they have no connections at our school will form new connections if they stay. Connecting socially is a drive that transcends differences. Maybe there are fundamental differences between two people, but at their core is a need to connect and understand one another.

It is important to wait for that quiet desperation that breaks through our indifferences to one another. Bonds formed in this way can be quite strong, far stronger than bonds between people who come together out of a common interest. Bonding despite differences is, in my opinion, the key to our future as a species. In this day and age of self-selecting into like-minded circles spanning the globe, we need to remember and cherish loving the other.

It starts here at A&I. Inside each of our students lie the components needed for making lifelong bonds with anyone. They just need to accept the fact that this is what they must do.

Life is hard, but we all have the strength to see it through. It involves standing our ground against our own demons, converting the pain into positive action. How we handle that speaks volumes as to who we are. It informs our future for many years to come.

When we lose students who are in the depths of such struggles, we ache a deeper ache than any other kind. It is extremely difficult because such struggles must be resolved from within. It is why “wise” people do not simply list off a prescription of actions. The struggle is personal and its resolution is personal. Each person finds their unique path and understanding of life in such struggles. No one can write their path for them. Perhaps the greatest tragedy of conventional education is that it sidelines such struggles and tries to replace it with a script. It fails and delays the ultimate reckoning of this struggle to a much later age with subpar results for the larger community and for the individual.

We can and do try to be a shoulder for students to cry on, but that mostly applies during the hot fires. The listlessness phase is often about suffering in the quiet darkness of the mind, a place that we staff can only obliquely offer comfort for. Directly shining a light on that struggle can rob the student of some of their own power and often causes the struggle to retreat for a time until it comes back in an even more powerful version.

All we can do is be present, supportive, and nonjudgmental. As staff, this is hard. For parents, it can be almost impossible to watch this.

Sometimes, the power to flee wins. That is the hardest time of being a staff. We can see the beauty that was set to emerge, the strength and unique wonders of a person just about to come into the world, only to see it flee and retreat, perhaps for years to come. Those are the days that I come home feeling gut punched, helpless to intervene, mute in my objections, locked into a box by the paradox of committing to individual freedoms and choices.

All I can do in the end is to hope that the spark out of the darkness happens before the final decision to leave is made. Or that parents can see the pain for what it is, love it, and, just this once, push their child to stay, saying “just one more year”.

Whatever the outcome, I know some mud-covered dancing six year old is about to waltz in the door and give solace to my aching heart, looking at me with that glance that tells me how important it is to keep this beautiful community brimming with life.

UPDATE: Aaron Browder at the Open School reblogged this with his own interesting commentary.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Giving Thanks

We have had an amazing year. A year ago at this time we had bought our new permanent home and were preparing to move in. It has been a busy year while we have grown into our new space.

Our student population has continued to grow and grow, roughly at the maximum rate we would be comfortable with, a rate which does not threaten the cohesiveness of our community. Word just spreads and we find our message of children being treated with respect continues to resonate.

We have a well-used and beloved green space with chickens, tree swings, fire pit, climbing trees, and...sticks! Neighbors have commented on what a joy it is to see children outside and playing freely and, gasp, even picking up their messes.

We have a separate music room where the rocking goes on without bothering the rest of us. Our students teach themselves how to play and they mutually improve their skills, challenging one another to do better.

We have a great kitchen corporation that delivers Hot Lunch Fridays. They plan the meals, make it, charge for it, and clean it up. It is quite a popular corporation.

We are also looking to hire a fifth staff member. Students stepped up to head the search and they have been doing an insightful and wonderful job of handling the applicants.

Our neighbors have been very welcoming and all of our interactions with officials have been pleasant. Even our noisy and crazy chickens have been warmly embraced by our neighbors.

Our community has also weathered the election. We had vigorous debates before and after, as well as the usual hyperbolic play that is perhaps the most cherished part of working with children. Free speech flows here, giving comfort to our very perceptive children about the deep stresses from this election. While in other places children might be left to their own dark musings, here they can explore those musings together, shining their light on the shadows of fear that melt away in the embrace of community.

We also came together to support another Sudbury school that was less fortunate. The school is Sudbury Schule Ammersee in Germany. They had opened with an enthusiastic community behind it, but the government refused to recognize that learning was happening there. The government thinks of human learning as coming in via information delivered by others instead of learning arising from experiential exploration of life.

We obviously disagree and we are fortunate enough to be allowed to coexist with those who view learning differently than we do. But other schools are not so fortunate. In Europe and elsewhere, there are Sudbury schools that are challenged and even shut down by the government. Children are not allowed to be free there. In some countries, any kind of private school is illegal.

We made a video of support for Ammersee: https://youtu.be/TJ8JhctE0Wk and stand ready to support them as we can. Spreading the word about our model is often all that we can do, but it is a powerful method for ensuring that we have at least a few places that offer the children to fully learn about life.

In this time of divisiveness, it seems that what we need to learn the most is how to come together, how to have differences of opinion, but still able to embrace each other with compassion and acceptance. It is hard to see how that can come from conventional schools that model top-down authority and constant judging leading, presumably unintentionally, to peer rankings and bullying.

But our school is founded on compassionate acceptance; we could not exist otherwise.

We hope our fellow schools find a way to convince their governments to accept that learning can happen in many ways. The benefits to our society of this kind of learning should not be underestimated.

Expect more to come in this space. The time to speak out is now.

0 notes

Text

Case By Case With Grace

by Joanna Franklin Bell (parent of two students at Arts & Ideas)

I spent a week visiting Arts & Ideas Sudbury School for five full days, just like a prospective student looking to enroll. However, at age 40-something, I am no student—my visiting week served to qualify me as a substitute (pending a School Meeting vote, of course) for when the staff might need just one more warm body to be present. Luckily for me, and unluckily for one sick staffer, I was that body for three days the following week, filling in while the beleaguered colleague recovered from pneumonia.

Here's what I learned during all of these days: Our children are amazing.

I could write paragraphs and paragraphs about the intense conversations I overheard, the gymnastic triumphs I witnessed, the songs that were written, the friendships tested and repaired, the games that were invented on the spot and then modified and played again, the disappointment when a project went badly, the thrill when a project went seamlessly, and the quirky learning moments that happen when kids realize that there is no rule requiring another kid to be nice.

The understanding of what the rules are and how they inform a day at Arts & Ideas is what brings me to write about JC. JC is the Judicial Committee, as we know, and it comprises a rotating team of students from the smallest to the biggest, a clerk (usually also a student), a scribe (often a student too), and any number of plaintiffs, defendants, witnesses, and observing flies on the wall like me.

As a visitor-cum-substitute, I am not allowed to vote, but I can participate. Twice I raised my hand to be called on by the clerk, and both times I discovered I didn't know the first thing about Robert's Rules of Order. I thought I did. I mean, School Assembly meetings where we parents gather to discuss and vote on the budget are run according to Robert's Rules, so I know about motioning and seconding and abstaining and all that. But when I had something pithy to contribute to a JC case, I discovered that my statement came at the wrong time. Once I started discussing sentences when the team was discussing charges ("Easy to confuse," the teenage clerk kindly said to me. "I used to do that too."), and once I responded to someone's sentence suggestion which was a waste of breath, since the sentence hadn't yet been moved. ("I suggest" and "I move" are two very different statements, and only the latter requires or invites discussion. And then only if it is seconded!)

What's noteworthy about Robert's Rules isn't simply that they keep people "in order"—they also parse the meaning of each topic down to its bite-sized bits so every discussion is intensely focused on just one item. What's even more noteworthy is that the current clerk, a child who's not even done growing and doesn't know yet what shoe size she will have for the next seven decades of her life, was able to easily steer the discussion back to that topic at hand without getting lost in the details that were often flying heatedly between a plaintiff and a defendant. "Be that as it may," she said to a boy who really wanted his opponent to go down for Hostile Physical Aggression, "that's a charge, and right now we're still discussing the findings."

She steered someone else in the right direction again later. "I understand your frustration that he cussed at you afterwards," she said, "but he's not the defendant right now; you are. If you wrote him up for Profanity, then we could discuss in a separate case whether he cussed at you after you pushed him."

I told a staff member later that this clerk must really be an exceptional one. "Well sure," was the answer, "but they all do what she just did."

Really? I couldn't. I couldn't have told you what was extraneous or relevant to a case, or the findings, or the charges, or the sentences. It all sounded relevant to me; I could not have dissected so neatly what was tangential and what was applicable. You know that statement that parents are so good at uttering? It’s this one: "I don't care who started it!" That's a statement you will never, ever, ever hear at Arts & Ideas, and certainly not in JC. "Who started it" is absolutely the crux of why a situation went south in the first place.

I left my first JC session dazed and speechless. I'd watched the parade of cases for an hour, knowing that I'd have to watch dozens more before I'd be able to wrap my head around the process. "So what did you think?" asked a staff member on my first visiting day, when he saw me exit the JC room with an indescribable expression on my face.

"I think that… if every kid had JC in their school, this world would be a different place within one generation," I answered.

The clerk's ability to adhere to Robert's Rules wasn't my only reason. I watched kids literally switch which side of the table they were on—JC team members (or a jurors, in the adult world) changed seats to become plaintiffs or defendants if they had a case that day. And plaintiffs and defendants swapped chairs all the time, having written each other up during the same (or a different) altercation. Here’s the most important part of my essay: In no situation did I witness shame. As a child, all I'd ever felt was shame when I was "in trouble," and ridding myself of that wretched emotion has been a huge part of my life's journey even—especially—now. I watched a current trouble-maker admit his guilt case after case and accept his sentences without any reddening of his face or ducking of his head. Another boy admitted guilt with the statement, “That’s what I’m like—of course I’m guilty!” I listened to a girl speak out of order (as I did, according to Robert's Rules) and not look abashed (as I had) when she was corrected. I watched another girl withdraw her motion when she changed her mind, without any over-explaining or face-saving rationalization for her reversal. I saw a plaintiff fling a baseless accusation… and the defendant didn't blink or even bother to respond right away. He was eating lunch, and finishing the popcorn bag first was more important than shooting down someone else's mistake right away. Besides, there was no point in responding, since JC wasn't currently discussing a motion; the other kid had been out of order and thus the words had no real effect. In short, I saw no sign of that ubiquitous guilty conscience that I've spent most of my life battling. No one was in disgrace.

Our kids here aren't presupposed guilty of anything. To heck with the apple and the snake—there is no original sin. They are free from guilty consciences. They own what they do wrong and plead guilty, which isn't the same thing as feeling guilty. If you take nothing else away from this essay, please take that statement.

If I took nothing else away from my week here, I took that realization. If our kids take nothing else away from their time here, I hope they take that freedom.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflections on my first year

My second year at Arts&Ideas has been a blaze of craziness with amazing times, as always.

At the beginning of the year, I felt the ghosts of the past year. In the spaces in between, I would see students who were no longer with us, their smiling faces and sing-song voices mere mirages. I reflected on the awesome rituals of the previous year, the wondrous times and just how much our students change and grow over a short summer.

From the beginning, I knew this year would be incredibly different just as last year was to the previous year. There are commonalities, of course, from year to year and space to space, but the unique chorus of our school carries a different tune and echoes in vastly different ways in different spaces with different people.

Already we have a large number of new students, students whose voices alter our communal song and take it in some other splendid direction. Some are quiet, some are loud, but they all are full of life.

The vantage point of our current space’s office that allows us to silently witness the crescendos of activities, the lows of cries, and the sweet silence of exhaustion, will be sorely missed. I will personally miss the office being part of the race and chase track. And I will miss the (Pink Panther) Cato-esque gauntlet downstairs I often had to run.

Attendance

There were several surprises that I encountered last year. Chief amongst them was the importance of attendance. Every member of the community has an important part to play in our chorus of joys and when one is absent, the whole song is diminished. We repeatedly witnessed the impact of a missing School Meeting Member on the individual as well as the community.

This was rather unexpected to me. I thought a great advantage of this school is that one could be out and not have to “catch up” on the missed work, something which can be quite debilitating in a traditional school. But our days are so full here that missing one day is missing far more stories and ideas than a traditional classroom’s content. Ironically, it is easier to catch up on textbook academics than one of our complex days.

We all struggle with the attendance policy. We want to be flexible particularly as we want our students to have chosen to be here. And yet at the same time, we need to consider the needs of the community and the impact of absent students. As always, we err on the side of letting them all be, but it is hard.

Democracy

Another surprise for me last year, and one I have written about before, is what democracy is truly about. Watching our politicians, one would think democracy is a game of winners and losers.

By being at our school, I have learned that democracy is about understanding. That is the real power of it. Sometimes a vote is close and contested, but those moments follow deep, respectful discussions where both sides are heard. That mutual understanding binds us even when we are deciding on divisive issues.

But it not just legislation where this occurs. This year, I am seeing how those same ideas of listening and compromise play out in JC and play out in everyday negotiations between students. And I witness that when interpersonal conflicts break out, it is almost always a result of them not listening to each other. The ever increasing level of shouting in those situations is a physical manifestation of each person’s increasing frustration that they are not being heard despite the sound waves hitting the ears.

The spirit of democracy is one of humanity’s finest possibilities and it is such a privilege to be in a community in which it flourishes.

Academics

I came in fully expecting no academics being pursued. But I was surprised. It does happen. It happens a fair amount actually.

But both last year and this year, those academics are done away from adults. And I have pondered why. My hypothesis, borne out from close scrutiny of my own daughter’s ways, is that there is this drive to do it themselves. Our students are learning many things, but the core learning is about learning.

And I think this makes them instinctively stay away from asking questions of experts. The students studying math have someone with a Ph.D. in math right here. What a great resource, says the traditional schooling mindset. But of all the questions I get asked, I think I have been asked about mathematics exactly twice in over a full year. Why? Because I already know the answer.

The focus of this school is on learning and students are focused on learning, though that is probably not a conscious realization. And if one wants to learn about learning, then one does not want to ask an expert about some topic. Instead, one wants to ask someone who can barely answer the question. When one does that, one gets to see the process of arriving at the answer. That is something that I, as an expert, can’t provide.

But I can provide that for a large range of possibilities. There are tons of stuff that I don’t know and so I get asked about those things. And what I do is make it very clear how I figure out the answer. That’s what they are looking for. I think that is also why very young kids have a habit of asking those “why” questions -- they are trying to find the point of ignorance of their parents and see how their parents handle it.

Context Switching

In a bit of reflection of what students do, I find that my day is a dizzying array of different activities. One minute I’ll be working on our building purchase and the next I’ll be working on unclogging a toilet and the next working on a database and the next dodging some racing kids and ….

The conversations I am a part of or witness run the gamut of human experiences and emotions. From pop culture that flies over my head to newly created games to some recent conflict over some item to issues of philosophy and religion, a single hour at this place makes my head spin.

This school sometimes reminds me of a manic mind, bubbling with ideas and energies. I can’t imagine a better way to spend my days.

I knew this place would be lively, but I had no idea how much life that does entail.

0 notes

Text

Embracing the Screen

by Caroline Chavasse

“One starting premise is that surely everyone has enough common sense to ensure that we don’t let the new cyberculture hijack daily life wholesale. Surely we are sensible and responsible enough to self-regulate how much time we spend online and to ensure that our children don’t become completely obsessed by the screen. But the argument that we are automatically rational beings does not stand the test of history; when has common sense every automatically prevailed over easy, profitable, or enjoyable possibilities? Just look at the persistence of hundreds of millions worldwide who still spend money on a habit that caused a hundred million fatalities in the twentieth century and which, if present trends continue, promises up to one billion deaths in the century: smoking. Not much common sense at work there. “

-Susan Greenfield neuroscientist, senior research fellow at Oxford University and a member of the House of Lords.

I heard Susan Greenfield, quoted above, a few weeks ago on the Diane Rehm radio show. There wasn’t much good she had to say about screens, which she seemed to pretty much boil down to anti-social video games and time-wasting social sites. I do not agree with Susan Greenfield, and yelled at the radio with almost every point she made. But there she was, a neuroscientist, speaking with authority and raising concerns—big, scary concerns on the public airwaves. From her book Mind Change, she writes, “Let’s enter a world unimaginable even a few decades ago, one like no other in human history.” (What generation couldn’t say that, or feel anxious because of it?) “It’s a two-dimensional world of only sight and sound,” (Well that’s one more than reading a book! (if she’s not counting touch, smells in the room...)) “offering instant information,” (Waiting for information is…better?) “connected identity,” (Does she mean our online identity? Does she not have an on-air-being-interviewed identity? Or a cocktail party identity? Or a House of Lords identity? At home in her bathroom identity?) “and the opportunity for here-and-now experiences so vivid and mesmerizing that they can outcompete the dreary reality around us.” (Dreary reality? I can’t even.) “It’s a world teeming with so many facts and opinions that there will never be enough time to evaluate and understand even the smallest fraction of them.” (So…better not bother learning how to evaluate or understand the small fraction you can use?) “For an increasing number of its inhabitants, this virtual world can seem more immediate and significant than the smelly, tasty, touchy 3-D counterpart.” (Conjecture! Hmph!) “It’s a place of nagging anxiety or triumphant exhilaration as you are swept along in a social networking swirl of collective consciousness.” (I think she needs to go online more (or at all?)) “It’s a parallel world where you can be on the move in the real world, yet always hooked into an alternative time and place.” Isn’t that what daydreaming is also?

Being ‘in the moment’ is not a natural human experience that the internet has now robbed us of. Whether we are proposing marriage, performing in a play, meditating, playing a sport, working on a juicy problem, dancing…we can sometimes achieve that being in-the-moment experience, if we are lucky or have trained very diligently, but I would argue that we are often hooked into an alternative time or place because that’s how our minds work.

I understand what she is getting at though. Those of us on Facebook have probably seen the post of the guy on a boat staring at his phone while a whale surfaces magically and beautifully ten feet away. Tsk tsk tsk! Missed it! (Hope that funny cat video was worth it. Or news from your sister that your mom broke her leg.) Which reminds me of another post (Oh, intarwebs!) that defends a mother who was heavily criticized (on another post!) for looking at a phone at the playground instead of watching her child playing. The critics said, “How in the world can you be checking emails when your precious child who-will-never-be-this-age-again is digging a HOLE?!?” The defenders said, “You don’t know what this mom’s day has been like! Maybe this is the first moment she has been able to have to herself, and being able to read an email from a friend may be the fuel she needs to be a loving and patient mom to her child for the rest of the day. Don’t judge, people.

So, yeah she’s a neuroscientist, I’m not. But most of what she said didn’t add up. If it did I would be working at a school with a bunch of anti-social dullards. Far from it. Kids have unlimited computer time at Arts & Ideas if they so choose. They also run around outside, build forts, debate veganism and write songs. They are not desperate to get screen time because it’s no biggie.

I also see, contrary to Ms. Greenfield’s assertions, that they are learning wonderful social skills; they are forgiving, humane and gracious with each other, even as the internet on which they surf can sometimes be cruel and ugly. Which leads me to another one of Susan Greenfield’s prophesies. She stated that kids who post things online and get “thumbs down” from anonymous viewers will be so devastated that they will curl up and die. With my son Louis’s (12) permission, I’ll tell you his story about posting on line. He started a few years ago—creating remixes etc.--and posting them on his youtube channel. I saw some really horrible, mean comments about his work that tore me up. I wanted to scream, “Don’t you know he’s just a little kid you jerks?!” Louis seemed upset by some (though he says he doesn’t remember it), mostly because he really wanted the respect from the community that he admired. And he wanted to do good work. I thought it was beyond what a little kid should have to endure. I ached for him. I tried be there if he needed me, but turns out he didn’t. For even though he was upset, he wasn’t discouraged. Getting feedback from his chosen community was more important to him than the few nasty comments. Today, he is an astute critic of his own work and is able to take the internet for what its worth. He’s developed resiliency, darn good internet smarts and yet has maintained a crucial vulnerability which allows him to keep growing.

Ok, enough mom-bragging but I could say the same about many of the kids I spend my time with at Arts & Ideas. I can’t even imagine Louis and other kids being ready for their world without this kind of experience and savvy—owning the internet, not being at the mercy of it. Yet Susan Greenfield is terrified for my child because I let him and his young brain go on it at will.

I overheard a conversation recently with two moms talking about what device one mom’s 10 year daughter could use but she was determined it would have NO GAMES or YOUTUBE!! I think she is trying to keep her daughter from having an existence, as Susan Greenfield wrote, “revolving around smartphone, iPad, laptop, and Xbox.” Though I imagine the mom would be okay with her daughter’s life revolving around friendships, news, challenging games or essays, poems and music. Hmmm. That’s like saying my existence shouldn’t revolve around paper and ink, but up until a decade or so it did in the form of magazines, newspapers, books, maps—which led me to celluloid, cathode rays and sound waves. Or just to a nice hike. It’s not the screen or device, it’s the access the device gives you to a multitude of worlds. Everything human, good and bad. Our kids have to deal with it, and they can. They are developing common sense through experience (how else can you?). And they probably won’t smoke either.

[Just overheard: “Scootering is my favorite part of the day.” - 6 year old who loves ipads.]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake JC

At our school, all School Meeting Members are equal. We all have equal voice and equal rights. But we also have equal responsibilities. This includes serving on our Judicial Committee where cases are discussed and dealt with.

When I have had the pleasure of interacting with JC, I have noticed that many of the youngest kids vote abstaining all the time. They look like it is way over their heads. Is this a case of expecting too much of young kids?

No, absolutely not.

First, they know that if they are not comfortable in making a judgement, then they can abstain and this is indeed what they do. Abstaining demonstrates how responsible they are. They are not simply voting with the majority or voting randomly. They are actively assessing their ability to make a sound judgement and, when they cannot do so, recusing themselves.

Second, the expectation that we are all equal is at the very heart of the model. We value all inputs and some of the greatest questions or observations have come from the young kids. They have plenty of value to offer even if they are not comfortable with making judgements.

Third, they are learning the process. We have plenty of evidence of how kids grow and mature into serving on JC. But I think my story below is perhaps the best evidence that they are engaged with it right now.

Kids learn by playing. They observe and then they re-enact, amplifying dramatic elements to increase the fun. The very same young kids that sit and can’t wait for JC to end are also the same ones that go and play at fake JC.

One day, I was walking along, minding my own business when I was called into fake JC as a plaintiff. I wise-cracked that I did not want to be called as is my right as plaintiff. The kid nodded, ran back, and moments later came back to call me in as a defendant; the other case had been dropped. Called into fake JC, I sat in the chair and was charged with hitting the plaintiff with a hammer. I pleaded not guilty and was sent to fake School Meeting, which happened right then and there. I was found guilty and suspended for a week. But I did argue for suspension with pay, which, being the generous folk they are, they agreed to.

Such is the way of learning with humans. We do not simply take in facts and rules like a machine. We observe and then we explore. I do the same thing when learning an academic subject or a new cooking technique or a new internet meme: observe or read about it and then start doing. Often, say in mathematics, I will take a solved problem and mutate it a little. Then I try to solve that new version, applying a variety of tools. It often goes poorly, but that’s not the point. I start to understand the process better by doing it and, indeed, failing at it. Thus, they play at fake JC to acquire the skill to be serious participants in actual JC.

Playful exploration is the serious business of learning. Seriousness is the application of skill while playfulness is the acquisition of skill.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Bold and Selling Well

We close our 6-part series on “Zero to One” with one inspirational quote:

page 21

1. It is better to risk boldness than triviality.

2. A bad plan is better than no plan.

3. Competitive markets destroy profits.

4. Sales matters just as much as product.

Let us color this through with the lens of Sudbury.

1) Traditional schooling is triviality. The unique pathways of Sudbury students is that of boldness. It is a risk, but one that usually pays off. The “safe path” is only safe if the economy has a need for the cookie cutter students that traditional schooling provides. In our current economy, that safe bet does not seem too safe.

2) This can be interpreted as it is okay to fail. Try something. You don’t need to succeed at the first go, but it should be thoughtful and iterative. Focus on something and see how it goes. Too often those from traditional school have been conditioned by lifelong grading that success on a first attempt is the goal. This is paralyzing and devastates the creative, playful spirit that we are born with. Make a plan, go for it, fail, try again, learning all the way.

3) If you play the same undifferentiated game as everyone else, then you will not be overly successful. You are taking on much risk of not being desired while limiting your potential earnings. But if you learn to be unique, then you can command impressive amounts of money. Sudbury schooling encourages each person to find their own unique and beautiful path through the world.

4) This is the heart of the matter. No matter how highly valued someone is, they need to sell themselves well. How does one learn to do that? By interacting with many others and getting what one wants through mutually beneficial negotiation. Sudbury students learn how to talk to people in an effective manner. That is what they are learning all day long whether they realize this or not. Traditional school students sit at desks with conversations silenced. The one skill that every individual needs to have is actively suppressed at traditional schools. This is insane.

Few people need any particular subject, but everyone needs to talk a good game. I read Hacker News, a site for startups and programmers. Over and over again, it is people skills that come to light as crucial and difficult. Newbie professional programmers very quickly realize that programming may be 20% of their job. Communicating with others, such as co-programmers, bosses, clients, future maintainers, past programmers, etc., are all very important to being a good programmer. The actual programming skill is a small subset of it. Of course, one does need to know how to program to be a programmer, but that is a specialized skill set, one that can be acquired as the need crystallizes. But being able to talk well to others is the common core of every role adults play in society.

At a Sudbury school, this skill, so vital to everything, is practiced non-stop.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seven Questions

Part 5 in our “Zero to One” series

Peter Thiel in “Zero to One” identifies seven questions that every startup should have good answers for. He goes into detail about the green tech bubble and how those companies failed to have good answers. Basically, they could see how there was great potential in the green tech industry, but they themselves did not have anything special beyond that generic insight.

So I thought it might be interesting to apply this list to Arts&Ideas and see how we rank up.

The Engineering Question

Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?

In terms of education, the Sudbury model is a complete change from what traditional schooling is. We do not incrementally improve, we leapfrog into a new paradigm.

The Timing Question

Is now the right time to start your particular business?

Yes. There is a growing notion that traditional schools are failing. They are doubling down with their testing ways with Common Core and all that. We see students increasingly living their entire childhood just to have a “well-rounded” resume to get into college. And then post-college, with no childhood and deep in debt, they find out that their path did not lead to comfortable employment.

Sudbury schooling offers a way for kids to be kids while at the same time getting truly prepared for future success. Now is the time.

The Monopoly Question

Are you starting with a big share of a small market?

If parents want to send their kid to a Sudbury school and live in the Baltimore area, Arts&Ideas is the only school. So far, Sudbury schools have not had to compete with one another. This may continue for some time, but we hope that changes for the sake of the many children living increasingly desperate lives at traditional schools.

The People Question

Do you have the right team?

At Arts&Ideas, we do. There are three basic groups in a Sudbury school: students, staff, and parents.

Our students are fantastic. The majority of students have complete buy-in to the model and the community. This, I imagine, is a very hard thing to get started initially. But once it starts, if the influx of new students is not too high a percentage (maybe 20 or 30% as a max), then the culture should help assimilate new students.

Parents are of a similar nature to students in that most will take their cues from other parents at the school. But as their interactions with each other are fairly minimal, they can certainly be off point. We are lucky with our parents largely being very much in sync with the model and understanding it, but even the best parents are constantly subjected to external pressures questioning their choice of this school for their children.

The staff are the third component. They obviously need buy-in as well, but more importantly they are the adult figures that students are around during the day. There is generally no teaching per se, but children do observe our behavior for possibilities to explore. So I think that suggests having a diverse set of staff is crucial. And at A&I, we have four staff that have very different personalities and interests. We are also all very respectful and professional in our manner. When we disagree, I like to think we model really good respectful arguing. This all bodes well for the future.

The Distribution Question

Do you have a way to not just create but deliver your product?

Not sure if it applies, but I will assume for us this means, do we have good facilities for students to be able to happily pursue whatever they feel like pursuing. We are working on it at the current time. It is looking hopeful, but even in the current place, there is plenty of room for most of what students wish to do.

The Durability Question

Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?

Tough question. There is no particular reason to believe that it will not be, but it is not entirely clear what happens if the Sudbury model becomes popular. Will there be an advantage to being the oldest one in the area?

The Secret Question

Have you identified a unique opportunity that others don’t see?

The idea that children are designed to learn on their own if we just get out of their way is not well accepted. Also the idea that children can run around on their own without close adult supervision is sadly also rejected by many. These are some of the foundational ideas that A&I is based on. They form a strong basis for much future success.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Focus or Diversify

Part 4 in our “Zero to One” series

Bet on the big bets. That’s the basic takeaway from Peter Thiel’s “Zero to One” chapter of Follow the Money. An analogy I have is that if you are going to gamble, gamble on the stuff that when you win, you’re set. If you have to keep playing, the odds will get you.

Every investor does diversify, but the smartest ones will only invest in those whose fundamentals could be big hits. Thiel uses the notion of the power law to demonstrate this. The basic idea is that the winners far outstrip the so-so companies. And with many failing, you need the big winners to make up the difference.

But life is not a portfolio: not for a startup founder, and not for any individual. An entrepreneur cannot “diversify” herself: you cannot run dozens of companies at the same time and then hope that one of them works out well. Less obvious but just as important, an individual cannot diversify his own life by keeping dozens of equally possible careers in ready reserve.

Our schools teach the opposite: institutionalized education traffics in a kind of homogenized, generic knowledge. Everybody who passes through the American school system learns not to think in power law terms. Every high school course period lasts 45 minutes whatever the subject. Every student proceeds at a similar pace. At college, model students obsessively hedge their futures by assembling a suite of exotic and minor skills. Every university believes in “excellence,” and hundred-page course catalogs arranged alphabetically according to arbitrary departments of knowledge seem designed to reassure you that “it doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you do it well.” That is completely false. It does matter what you do. You should focus relentlessly on something you’re good at doing, but before that you must think hard about whether it will be valuable in the future.

I think these are exactly the lessons that students at our school naturally learn. They are free to experiment, to do this or that for however long they like. And there are many stories of students, particularly older ones, spending a long time on some particular task. And then they move on. Eventually, they get to a point where they know they can accomplish whatever they set their mind to and then understand the value proposition for it.

What I find interesting is that in traditional schools they do not let students master the subject. Mastery requires time and freedom to explore. But they are given a fixed amount of time with a fixed pathway through the material. Deviations are not permitted even though deviations are exactly where deep learning happens.

At a Sudbury school, those who are interested in pursuing an academic subject can do so as much as they like. Few do as that is not something which the majority of people find interesting (how many math majors are there, after all?), but it feels like a great tragedy when there is someone interested in mastering an arcane subject who is prohibited from doing so in the name of education.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Negotiation

by Phil Glaser (Staff at Arts & Ideas Sudbury School)

I just witnessed a piece of an exchange among the little boys here at school that almost seemed tailor made to demonstrate the development of negotiation, a key skill of life here (and beyond). I went into the big room to have my lunch where a group of four boys was playing with the mats. I had come in during the middle of some kind of argument between two of the boys about who could use what mats. One of the four was maintaining that a school rule reserved his right to use the mat, while another maintained that the golden rule would dictate that he should have the mat. This argument went into an explanation of each rule and a discussion of the merits of the institutions where each got their respective rules: school and church. This, in addition to prompting a number of declarations and indictments (e.g. “You’re not my friend anymore!”), developed into a discussion of whether god was “real or fake” (to use their language). Quite a serious conversation the argument about mats turned into!

The kids were moving around and continuing to play the whole time that the two arguers were trying to win each other’s support as well as that of their audience. Child #3 was musing out loud about points made on either side (e.g., “If something isn’t real, then it’s dead”) and rolling around on the ground. At this point, child #4 breaks into the argument saying, “Hey, guys! Guys, who are arguing!” He didn’t really follow up with a specific message, but, with his hands raised in entreaty like a mini MLK, the argument essentially stopped. The game moved forward to other fun and other arguments (they are still playing in the same area and managing the same small disagreements as I type).

The process of negotiation seems to start out with an argument about what is right and what is wrong on a very visceral level. All participants are, at first, 100% sure of what they know because it’s what their parents have told them directly or what their upbringing suggests must be true implicitly. At a certain point, it becomes apparent that everybody is as dead-sure as you are, so something’s gotta give. It emerges over time through loggerheaded debates as the one described above that in a situation where opinions differ, the value that remains consistently worthy is to just get along. Kids, when allowed to stray from the relative cultural homogeneity of the home and enter into the uncertain world of difference, find that they’d rather stay friends than be right. The skill of making peace despite seemingly incompatible dispositions is one that isn’t present enough in our world. I consider what is offered here, in our willingness to remain hands-off, an irreplaceable opportunity for its development.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Humans Need Not Apply

Part 3 in our “Zero to One” series

There is a video that I highly recommend watching: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Pq-S557XQU Go ahead, watch it. I’ll wait….

Back? Scared? Next, you should probably read Chapter 12 of “Zero to One” by Peter Thiel. The title is Man and Machine.

The idea of the video is that machines will replace humans at their current tasks and that will end poorly for humans. The idea of the chapter is that machines will complement what humans can do.

Whose right and how does this matter to a Sudbury education? Routine tasks will almost be certainly done by machines. They could be done today, except outsourced labor is currently cheaper than the robots that could be brought in. But as robots become ever more multi-purposable, the costs will come down.

This should free humans from having to do tedious or dangerous work. Routine work is not something that humans are particularly well-suited to do. Instead, humans are great at figuring stuff out, being unique, and wandering into random goodness.

We find recognizing a picture of a cat to be a trivial task while currently that task is very hard for computers. Yet for us to compute the sum of a 1000 numbers is extremely hard (unless there are shortcuts!) while computers can do that faster than I can blink.

This is Thiel’s point. Let machines do what they are good at and let us do what we are good at.

Think of what professionals do in their jobs today. Lawyers must be able to articulate solutions to thorny problems in several different ways---the pitch changes depending on whether you’re talking to a client, opposing counsel, or a judge. Doctors need to marry clinical understanding with an ability to communicate it to non-expert patients. And good teachers aren’t just experts in their disciplines: they must also understand how to tailor their instruction to different individuals’ interests and learning styles. Computers might be able to do some of these tasks, but they can’t combine them effectively. Better technology in law, medicine, and education won’t replace professionals; it will allow them to do even more. (p. 147-148)

In other words, the key to succeeding in the future is in being able to team up with machines, utilizing their strengths to process lots of data while relying on human strengths to recognize what those results mean and how to communicate them.

We need people who are very inquisitive, alert, intelligent. Mastery of facts and simple (rule-based) skills are not going to be very valuable. Being alive with curiosity is. This is exactly what Sudbury schools have to offer.

But the most valuable companies in the future won’t ask what problems can be solved with computers alone. Instead, they’ll ask: how can computers help humans solve hard problems? (p.149-150)

Just as some of the most prized skills across employment are those of being able to work effectively with others, so too the skills of interacting with computers will be of great value. It is exploration, partnership and cooperation which is the essence of what is (will be) needed. And this is what we see our students practicing every day.

0 notes

Text

Competition or Cooperation

Part 2 in our “Zero to One” series

A very strong theme throughout the book “Zero to One” by Peter Thiel is examining the economic truth about competition. He argues that competition is destructive, cooperation is beneficial.

The airlines compete with each other, but Google stands alone. Economists use two simplified models to explain the difference: perfect competition and monopoly.

"Perfect competition" is considered both the ideal and the default state in Economics 101. So-called perfectly competitive markets achieve equilibrium when producer supply meets consumer demand. Every firm in a competitive market is undifferentiated and sells the same homogeneous products. Since no firm has any market power, they must all sell at whatever price the market determines. If there is money to be made, new firms will enter the market, increase supply, drive prices down and thereby eliminate the profits that attracted them in the first place. If too many firms enter the market, they'll suffer losses, some will fold, and prices will rise back to sustainable levels. Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.

The opposite of perfect competition is monopoly. Whereas a competitive firm must sell at the market price, a monopoly owns its market, so it can set its own prices. Since it has no competition, it produces at the quantity and price combination that maximizes its profits.

....

Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition, all profits get competed away. The lesson for entrepreneurs is clear: If you want to create and capture lasting value, don't build an undifferentiated commodity business.

And this is the crucial point that applies to people as well. Every individual should consider themselves a company as well. If you are undifferentiated from others, then you will not be able to demand large sums of money for your services. In fact, you may not even be hirable.

But if you have cultivated uniqueness, something that makes one different and attractive to others, then you can capture good value.

Traditional schooling focuses on making undifferentiated labor. Sudbury schooling allows for the natural growth of students into whatever unique individuals they desire to be.

Even the basic notion of grading is that of competition. As a long time teacher in other contexts, I know that I can design tests that all students could get A's on or that they could all get F's on. The only truth that grades reflect is a relative measure between test takers, gauged on some arbitrary scale. Competition is the heart of the grading process.

Contrast that with a Sudbury education in which cooperation is how many students spend their days. Constantly negotiating, constantly bickering, constantly shifting in their activities, they are about being individuals cooperating with other individuals to accomplish their own desires. This is their days when they are young. As they get older, they settle down and focus on whatever they are interested in, delving deep. They are learning exactly what they need to be a fantastic, creative human monopoly.

0 notes

Text

Educational Preparation

This is the start of a series of posts examining the ideas in the book “Zero to One” by Peter Thiel (co-founder of PayPal, amongst other accomplishments) in the context of a Sudbury education. It is my thesis that the kind of ideas he talks about in this book directly support the value proposition of a Sudbury education beyond the obvious humane treatment of children that this model provides.

This post will cover a few choice quotes about his feeling towards a standard education. In later posts, we will delve into the more nuts and bolts of startups and how they relate to Sudbury.