Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Animator Spotlight - Milt Kahl

Outside of my childhood, I never really had an interest in the classical Disney films; they were always such a ubiquitous property that their constancy in my life rendered them inert to me, in a way - the Mona Lisa becoming a refrigerator magnet you see every day, eventually forgetting it's even there. Disney's constant re-use of characters for marketing purpose doesn't aid that sense of over-saturation leeching the effect from these pioneering pieces of animation history. However, with this course I have been taking the opportunity to revisit them, to try to peel back the heavily varnished layers and see into the back where the hard work of the animators was being done.

In a previous post, I discussed interviews done with two of the "Nine Old Men", a group of animators that arguably comprised the bedrock of the Walt Disney animation studio's success over the better part of the 20th century, helping shape the company through their successes. These two - Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston - are undoubtedly incredibly talented animators in their own right, but I can't truthfully say that either is my favourite of the classic Disney animators - that goes to the inimitable and controversial Milt Kahl (1909-1987). Kahl is an incredibly influential figure in animation history, although he is considered somewhat divisive in certain circles for not only his broad, exaggerated animation style that some consider lacking in subtlety, but also his excess of personality which was often a source of conflict in the studio as well as his personal life - Kahl had three wives.

In order to understand this titan of the industry a little better, rather than sourcing a single article, I have sought out a number of interviews, accumulated histories, and first hand accounts from a variety of authors and sources. This allows me to compare several of viewpoints and portrayals of history, to ascertain whether bias coloured the author's view of events. These articles will be listed below in the references section.

Milton Erwin Kahl was born March 22, 1909 in San Francisco, California, where he began drawing at around 6 or 7. Kahl had a challenging childhood, growing up poor and without a father for most of it, the man having abandoned his family. Kahl was even said to have began his drawing career on toilet paper, his family unable to afford him drawing paper. Kahl's life continued to get harder, as he left high school early, or as Disney's website claims, quote:

"He cut his high school education short, however, to pursue his dream of becoming a magazine illustrator or cartoonist."

Judging by his family's lack of financial means, as well as his propensity later in life to be argumentative and outspoken, it's safe to say he dropped out of high school for reasons other than his own choosing, and Kahl was said to have bore a chip on his shoulder for the rest of his life for not having a more formal education. As a young adult Kahl took on various positions to make due, finding success working on the art departments for the Oakland Post Enquirer and the San Francisco Bulletin. Unfortunately, the Depression hit and Kahl was let go. Other jobs were less glamorous, such as designing advertisements on cards for children's movie theatres, a job he lost to an outburst of his rage.

youtube

Milt Kahl was well-known for his often explosive temper.

In 1933, a contact he made at the Oakland Post Enquirer, Ham Luske, recommended him towards Los Angeles, where the fledgling Disney Studio was hiring artists to become cartoonists. Having an interest in animation and having little other options at the time, Kahl applied and was hired by the studio in late June 1934. Due to his lack of secondary or post-secondary education, Kahl was not immediately rocketed to success at Disney (in no doubt partially due to his propensity to swear like a sailor as well) but was allowed to work on projects such as the short 1936 short Mickey's Circus, as well contributing animation to Snow White.

youtube

Kahl's "big break" however, would come about during Disney's troubled production of 1940's Pinoccio. Animators on the film were struggling to portray Pinoccio appealingly and Kahl, outspoken as ever, loudly announced he wasn't a fan of the work being done so far, to the other animator's chagrin. Ham Luske, now the director of this project, politely offered Kahl to put his money where his mouth was, and to draw something better. Unlike the other animators who had drawn the character more "puppetlike", emphasizing this in his appearance and movements, Kahl chose to draw Pinoccio as more human, drawing the wooden joints on top afterwards. This simple yet effective solution proved successful at making a more appealing character, and Kahl's word became more heavily weighted in the studio's exchange of ideas.

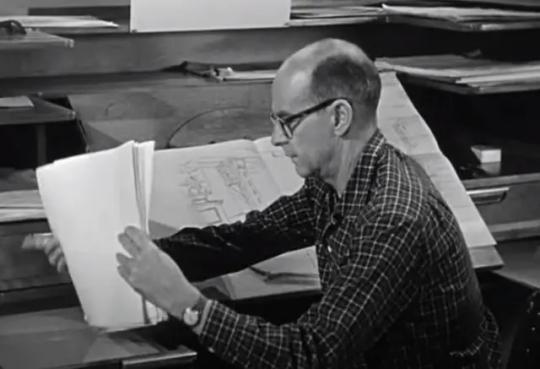

Drawings by Kahl. Note the peg holes at the bottom - these were likely done while at Disney Studios.

From then on, Kahl was unleashed. Now that the other animators respected his skill, his personality could truly glower through. Young animators were warned never to disturb Kahl while he was animating, lest they invoke his ire. He was known for being "cold, competitive, opinionated and a perfectionist" - a personality that might easily result in disciplinary action or even firing at another job, but so respected was his output as an artist that younger animators would dig through his wastebasket to to take his discarded drawings as inspiration for their own work. It's easy to see why - Kahl's work has an effortless quality and legibility that makes his work extremely appealing.

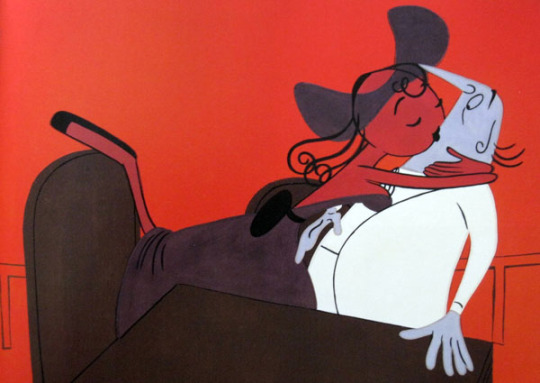

Some of Kahl's work on The Sword in the Stone.

Kahl would continue to succeed at Disney, but it was not until the 1960's where his influence would truly begin to expand. Although Kahl was supervising animator on many projects, it's understood that he wasn't always a fan of them. As I mentioned, Kahl preferred exaggerated characters with a highly pronounced personality, and in animation you don't always get the scene you want to work on. Sometimes he would be called to work on more restrained characters like Prince Phillip in Sleeping Beauty - a task he complained bitterly about. It wasn't until 1963's The Sword in the Stone that he served as both animation director and character designer. He began to care less and less about "appeal" of a character and more its personality and kinematics. Think about some of the characters we are with the longest in the film - the gangly pre-teen "Wart", the wizened old Merlin and the malevolent crone Madame Mim. It's hard to imagine these characters in a film like Snow White - they're clearly not trying for that kind of appeal, there's no interest in being cute, and yet the drawings are undeniably successful.

Kahl designing Shere Khan from The Jungle Book.

That's something that always sticks out to me in watching Kahl's animation - the drawings. Obviously, right? But it's often easy to forget when watching animation - you're watching hundreds, often thousands of drawings flashing past you at 24 frames per second. It's rare that a single image can make an impression on you at 1/24th of a second, but I find that Kahl's drawings often do. The looseness of his pencil marks translate extremely well even through motion, where it might otherwise come off as rough and unfinished, the marks simply adding texture to the drawing. Upon rewatching 1967's The Jungle Book recently, I was extremely charmed by the personality overflowing from every scene, at least as far as the animation itself goes. Not only is there an extremely solid understanding of how some of these animals work in display of characters like Shere Khan and Bagheera (some, like Baloo or Kaa, are much more exaggerated) but there is so much of the classical animation maxim of not just trying to make something move on screen but to make something feel truly alive.

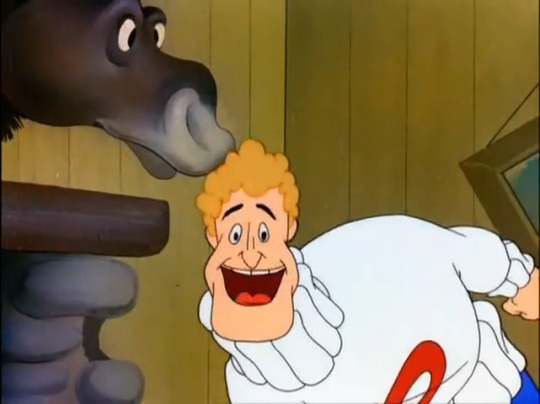

The "Milt Kahl head swaggle", as it has come to be known.

I would be remiss to discuss Milt Kahl without bringing up the "head swaggle", one of Kahl's animation signatures. It is a particularly memorable bit of animation showboating which involves a character speaking while waggling their head back and forth in a sort of pompous, self-satisfied manner, requiring a huge amount of tracking on the mouth movements while considering the underlying body mechanics. This bit of character animation is, in most cases, entirely unnecessary, but still provides an excellent opportunity for Kahl to use his incredible ability to make a movement feel fluid and natural. Managing to make such a movement feel genuine, one that if drawn by a lesser animator could easily feel awkward and artificial, is a testament to Kahl's ability, to say the least.

Thumbnails for The Rescuers, drawn by Kahl.

Kahl would continue working for Disney for forty years, having contributed to animated films up to The Rescuers, a film of which he was extremely critical. Ultimately, however, he was displeased with both the direction the studio had gone since its heyday as well as the horde of younger animators clawing their way up to fill the gap of power left by more senior artists slowly retiring or being replaced, and he too left the studio in 1976, retiring to the San Fran bay area to pursue his own artistic goals such as wire sculpture. He would pass away on April 19, 1987.

Kahl was irascible, loud-mouthed, brutal and blunt, but he was also an incredible animator who had a capacity for great heart. It was surprising to learn that he would often take time out of his busy schedule to help other animators who were struggling, and Brad Bird, who studied under Kahl, described him as "tough, but in a gentle way", helping him to improve his drawings where they needed it most. Kahl was often scathingly critical of others' work, but he expected that level of perfection from himself as well. I think it is beneficial for anyone with an interest in art to consider his ethos when examining your own work - while perfection is not always possible, striving for it is still desirable and often produces the best results.

References:

https://mkahlillustrator.co.uk/blog/milt-kahl/ - Matthew Kahl

https://jimhillmedia.com/king-kahl-a-personal-look-at-disneys-master-animator-milt-kahl/ - Floyd Norman

https://50mostinfluentialdisneyanimators.wordpress.com/2011/10/21/7-milt-kahl/ - Grayson Pointi

https://www.waltdisney.org/blog/milt-kahl-master-puppeteer - Tracie Timmer

https://www.cartoonbrew.com/disney/the-milt-kahl-head-swaggle-80861.html - Michael Ruocco

http://www.michaelbarrier.com/Interviews/Kahl/Kahl.html - Michael Barrier and Milton Gray

http://andreasdeja.blogspot.com/2011/06/milt-kahl.html - Andreas Deja

https://d23.com/walt-disney-legend/milt-kahl/

0 notes

Text

Animation and Design in Team Fortress 2 - Valve Software, 2007

One of the most iconic video games of the 2000's, Team Fortress 2 (TF2 for short) has become famous even outside the bounds of traditional gaming culture. As a multiplayer first person shooter (FPS) in a decade already suffused with games of that ilk, TF2 managed to set itself apart from its competitors through its unique art style, its pronounced sense of humour, and its incredibly memorable "Meet the Team" promotional animated shorts, and has gone on to have a legacy that has lasted almost 20 years after its release, especially in use through Valve's proprietary "Source Filmmaker" software, using the game's models and maps as an endlessly useful toolbox for fans looking to emulate the game's humour. But how did such an off-kilter yet wildly successful game come into being?

Team Fortress 2's title screen, from later Meet the Team videos.

Although not common knowledge, Team Fortress actually has its roots in a much older game - id Software's seminal release, Quake. Quake was already a massively influential game in terms of how it was rendered as compared to earlier titles like Doom, which utilized a "2.5D" style - having environments that were essentially 3D through use of rendering tricks while still utilizing 2D sprites for its enemies, props, and the player's weapons. Quake featured, in contrast, fully modelled polygonal 3D characters, environments and even viewmodels for weapons. Although they are comparatively primitive when compared to modern graphics, Quake's jump in fidelity from previous titles created a major splash in the industry.

Team Fortress' 9 player classes in the original mod for Quake.

Aside from pushing technical boundaries, id Software titles are also famous for another important facet of their longevity - modding support. Modding, in game terms, is when fans of a game edit the game's code, graphics, even gameplay to dramatically change the experience far beyond the developer's original intentions. The original Team Fortress was one such mod, changing the frenetic yet ultimately self-serving style of Quake's deathmatch-style multiplayer into a class-based, team vs. team objective. Developed by Robin Walker and John Cook, the mod became extremely popular and developed a large number of "clans", organized groups of players who would host servers and fight in competitive matches against one another.

Early promotional screenshots of Team Fortress 2, then subtitled "Brotherhood of Arms", showing one of its first art styles - at this point the game was designed to have a realistic military aesthetic.

In 1998, following the success of their first game, Half-Life, Valve Software, a company founded by Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington, were looking to find their next project after Half-Life's rocky production schedule. Having enjoyed the TF Quake mod themselves, Valve hired Walker and Cook to work on an adaptation of Team Fortress for the Goldsource engine, eventually releasing as Team Fortress Classic. After this, they quickly began working on a sequel, the game that would become Team Fortress 2. However, they could not imagine the challenges that creating TF2 would produce. The game would ultimately take over 9 years to develop, and over the course of that near decade-long development cycle the game would drastically change art style and gameplay goals multiple times, with years of work often being thrown away to keep up with technological changes.

Concept art for the "Heavy Weapons Guy", one of 9 classes in TF2.

Eventually, some time after switching to the Source engine that powered Valve's flagship release Half-Life 2 in 2004, the choice was made to abandon the game's original intended realistic military art style in terms of a much more exaggerated, cartoonish look inspired by the work of early 20th century commercial illustrators such as J. C. Leyendecker, Dean Cornwell, and Norman Rockwell. Textures created for the characters and environments were painted with visible brushstrokes or are based on photos that are edited by hand to appear more stylized. The maps are designed with an "evil genius" theme, featuring archetypical spy fortresses, hidden inside inconspicuous buildings such as industrial warehouses and farms to give plausibility to their close proximities. These bases hide exaggerated super weapons such as laser cannons, nuclear warheads, and missile launch facilities, which serve as the in-game objectives during matches.

TF2's 9 classes and their silhouettes.

One of the most important factors of TF2's artistic success is its intent towards readability during the chaotic fracas of player-vs-player gameplay. Their colour schemes, while primarily used to help distinguish between each team (RED and BLU), also uses contrast on the character's model to help draw the player's eye towards the model's chest, where the weapon is held - quickly allowing a player to determine what kind of threat an enemy might pose. Each of the 9 playable classes were designed to be immediately recognizable at any range, mostly through their distinct silhouettes and use of animation. This also allowed each class to develop its own distinct personality - a Soldier will lumber about with his bulky rocket launcher, while a Spy lurks in the shadows with his deadly backstabbing butterfly knife.

Screenshot from "Meet the Heavy", first of the promotional "Meet the Team" videos.

This strong emphasis on personality, though originally a gameplay mechanic, ultimately proved to be one of TF2's strongest thematic elements as well, leading to the creation of the "Meet the Team" animated shorts. Originally based on the audition scripts used by the actors such as Gary Schwartz, who plays the "Heavy Weapons Guy", the shorts utilized the updated Source engine's new faceposing technology, allowing these stylized character models a broad range of ability to emote. Their personalities are immediately apparent to anyone who watches these brilliant shorts - the Heavy's love for his absurdly giant gun, the Sniper's relaxed professionalism towards his assassinations, the Medic's unhinged joy at being able to toy with human life, these larger-than-life characters are beautifully realized with both broad and subtle touches through design and animation.

youtube

An example of a fan-made Source Filmmaker animation, using an audio clip from Futurama.

The "Meet the Team" videos were an immediate success, portraying the game's unique style on a level that some compared to Pixar Studios' work. Eventually, Valve would release the tool they used to create these animations - Source Filmmaker. Using characters and maps from TF2 and other Source engine games, fans could create their own animations for free, ranging from low-effort shitposts made in a few days for a laugh to full-length professional level features with highly polished animation and custom voicework. The community's skill was such that from 2011 to 2017 Valve ran the "Saxxy Awards", named after the in-game character Saxon Hale. This annual worldwide competition was held for any 3D animation made in SFM, receiving hundreds of submissions at its peak and originally hosting 20 categories for submission, with winners receiving a special limited release in-game weapon as a prize.

Screenshot from "Meet the Pyro", the final "Meet the Team" short released by Valve.

The SFM community is still strong today, although its aging technology and its association with pornographic depictions of characters from other games like Overwatch have tarnished its reputation somewhat. Despite this, it is hard to overstate how much of an impact Team Fortress 2 has had in the course of its 17 year lifespan. Not only has it influenced my artistic development, I have personally put an unconscionable amount of time in public servers and playing with friends over the years, and while I don't find myself going back to play it nearly as often these days, I am always filled with warm memories of the good times I had whenever I see the character's distinctive, goofy mugs.

Sources:

https://wiki.teamfortress.com/wiki/Team_Fortress_2#Development

https://wiki.teamfortress.com/wiki/Hydro_developer_commentary

https://wiki.teamfortress.com/wiki/Well_developer_commentary

https://wiki.teamfortress.com/wiki/Gravel_Pit_developer_commentary

0 notes

Text

Space Ghost Coast to Coast - Season 1 Episode 6 "Banjo" (Air Date Sep 10, 1994) - Dir. C. Martin Croker

When it comes to TV, sometimes one man's trash is another man's treasure. Such was the case with Space Ghost Coast to Coast, a show loosely cobbled together out of detritus of the airwaves to appeal to the cynical Generation X that became iconic, by all accounts, entirely by accident.

DVD Cover for SGC2C.

Before we can discuss the bizarre place Space Ghost found himself in the 90's, we have to go back 30 years. Originally created by Alex Toth (1928-2005) as an action-oriented break from the "funny animal" comedies that were frequent fare of Hanna-Barbera Productions, Space Ghost was nonetheless fairly typical of HB cartoons, utilizing an extremely limited animation style that made frequent re-use of cels and animation cycles in order to produce a Saturday morning superhero cartoon as quickly and cheaply as was possible. The plot involved the titular Space Ghost, along with his two teenage sidekicks Jan and Jace and their pet monkey Blip, as they travelled through space and battled against a number of nefarious villains, such as Zorak, Brak, Moltar, and a number of other now far less memorable characters such as "The Spider Woman" and Metallus.

Model sheet for Space Ghost 1966.

Although it was considerably popular at the time of its release, spurring a wave of superhero themed cartoons and merchandise following its airing, production on the original Space Ghost cartoon lasted only a single year with a grand total of 20 episodes. This was just one example of Hanna-Barbera's prolific production schedule, as the studio aimed for a maximalist style aiming to flood the market with a "quantity over quality" mindset. Ultimately, however, this lack of craftsmanship would be their downfall. By the 1980's, Saturday morning cartoons had lost their profitability and the studio was in economic freefall. The studio's monetary woes eventually led to the acquisition of Hanna-Barbera properties by media mogul Ted Turner and his Turner Broadcasting System, the studio's assets being folded into Warner Brothers entertainment.

Cartoon Network's logo from 1992-2002.

Shortly after this acquisition, TBS launched its burgeoning Cartoon Network channel as an outlet for its now expanded animation library. Vice President of the network, Mike Lazzo, was tasked with creating a cartoon aimed at appealing to adults, with only a single requirement - the show would have to be dirt cheap. With this in mind, Lazzo turned to the recently acquired HB properties and eventually settled upon Space Ghost. Cobbled together by Andy Merrill (the voice of Brak) and Jay Edwards out of archival footage of the original cartoon and footage of press junket interviews with Denzel Washington for Malcom X, a proof-of-concept pilot was created. Here is where things truly begin going off the rails - the first Adult Swim cartoon was coming into existence.

Space Ghost at his desk.

SGC2C first aired on April 15th, 1994 as the first original Cartoon Network production. The concept started relatively simply; the eponymous character had grown tired of the superhero game and had instead retired to host a late-night talk show, utilizing his imprisoned foes from the original show as crew. The character of Space Ghost (voiced by Gary Owens in the HB cartoon, now recast as George Lowe), once a noble and honourable bog-standard hero type, was reshaped into a "clueless, fabulously self-important" media personality who would interrogate guests with baffling non-sequiturs. Villains Zorak (a giant mantis) and Moltar (some kind of magma-man), both voiced by director C. Martin Croker, served as bandleader and director/producer respectively, both participating as part of the show against their will, under duress of being exploded by the unhinged Space Ghost's wrist lasers.

Zorak tickling the ivories.

The show's production had to be innovative considering its shoestring budget. The "set' was created out of plastic and plexiglass with the characters' reused animation projected on top. In the rare instances the producers required new animation, they utilized rotoscoping, a style where animators trace over live action footage frame by frame, to fill the gaps in the old assets, adding grain and imperfect lines to match the original cartoon's style. For the interview segments, they used a tiny motor to descend a miniature TV monitor from the ceiling to display the live action footage of the pre-recorded interviews with celebrity guests.

"Weird Al" Yankovic, the first celebrity guest to actually request to be interviewed by Space Ghost, from the episode "Banjo".

As previously mentioned, I have selected the episode "Banjo" ("KING OF THE SEA MONKEYS!") but all the episodes are more or less interchangeable, featuring animated insanity mixed with live-action interview footage. When it came to the interviews (after asking if the interviewee had enough oxygen or what superpowers they possessed), the footage would be cut and edited to create a number of awkward pauses, and seemingly reasonable responses to questions asked during the live interview would be repurposed by having Space Ghost asking a completely different question during the cartoon, resulting in the interviewee appearing almost as insane as Space Ghost himself. Space Ghost would often become angry or distracted during the interviews, sometimes becoming lost in an entirely imagined storyline in his head. Although the show was scripted, George Lowe was allowed leeway with ad-libbing dialogue and would occasionally interject with nonsense to surprise the interviewee. Most guests enjoyed the humorous incongruity of the show's format, although occasionally a guest, such as Paul Westerberg of the band The Replacements, would have enough of the insanity and would walk out.

youtube

Despite its absurdist tone and incredibly cheap production, the show was a relative success and quickly became Cartoon Network's first hit show, even garnering fans at NASA, who named rocks found on Mars after Space Ghost, Zorak, Moltar, and Brak during 1997’s Pathfinder mission. Although there were rumours that Space Ghost creator Alex Toth was displeased with the bastardization of his work, he disproved this with written letters stating he appreciated any adaptation of his characters. The show would go on to spawn a number of successors, including Cartoon Planet, a somewhat direct continuation of the series in a variety show format, The Brak Show, a series based around the childlike Brak in a pastiche of 50's family sitcoms, Aqua Teen Hunger Force, an equally absurdist and crass series based on characters debuting in the SGC2C episode "Baffler Meal", and Harvey Birdman, Attourney at Law, another Adult Swim property that reused Hanna-Barbera characters in modern context, although this program utilized far more original animation as Space Ghost had proven the formula successful and thus allowed for a higher budget. Additionally, absurdist comedian Eric Andre would claim SGC2C as a major inspiration for his bizarre, nightmarish talk show The Eric Andre Show, stating he rewatched the entirety of the series to gain insight into how to properly unsettle guests.

The show would be cancelled and revived several times, and its legacy lives on today through Adult Swim's current roster of dadaist humour based cartoons. Although it is not my favourite of the Adult Swim roster, I carry a place in my heart for SGC2C for its trailblazing absurdity and long lasting influence. Tragically, director and voice actor on the show C. Martin Croker died abruptly in 2016, and an outpouring of support from fans of his work followed.

References:

https://hazlitt.net/blog/last-time-things-made-sense-space-ghost-coast-coast-20

https://consequence.net/2024/04/space-ghost-coast-to-coast-anniversary/

https://thehundreds.com/blogs/content/space-ghost-coast-to-coast-how-one-networks-trash-became-anothers-bizarre-treasure

https://www.indiewire.com/features/commentary/space-ghost-coast-to-coast-30-anniversary-cable-tv-delight-1234973555/

https://www.cracked.com/article_39518_tell-me-about-your-trousers-the-voice-of-space-ghost-reflects-on-space-ghost-coast-to-coast.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Critic (1963) - Dir. Ernest Pintoff

After the last entry in my film journal focusing on Rooty Toot Toot and its rather highbrow artistic aspirations, I thought it would be a charming change of pace to focus on a relatively simple short that lampooned these high minded ideals - 1963's The Critic.

No, Jay Sherman is not involved.

Written and directed by animator Ernest Pintoff, a jazz musician who also had dabbled in visual arts, eventually discovering and participating in the animation scene of New York during the 50s and 60s. Pintoff was considered on the bleeding edge of cool at the time, and his self-funded abstract art pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable as widespread entertainment, though his style was not without its criticism.

After befriending legendary comedian Mel Brooks, the mind behind the incredibly successful films such as The Producers and Young Frankenstein, Pintoff was inspired by an anecdote that Brooks relayed of a screening of a Norman McClaren short. McClaren's works were known for their surreal imagery and lack of a traditional plot structure, and an elderly immigrant in the audience was loudly complaining about these perceived shortcomings. Pintoff was amused by these events and found the man's frustrations relatable, and so Brooks and he began working on what would become The Critic.

"What da hell is dis."

The short is entirely comprised of abstract visuals of geometric shapes on a brightly coloured backgrounds as a harpsichord plays elegantly behind. As the film progresses, the voice of an unseen narrator, apparently a member of the audience of this film within a film (voiced by Brooks in a manner similar to his character The 2000 Year Old Man, described as an "ancient Jewish gentleman"), begins to bemoan the nonsensical nature of the movie he has paid 2 dollars to see. Ignorant or unmoved by the author's symbolic intent, the man continues to loudly complain despite the protests of his fellow audience members.

"Looks like a bug."

Improvisation played a heavy role in The Critic. The avant-garde visuals, created with full artistic liberty by Pintoff's cameraman Bob Heath, were intentionally made to feel shallow and pretentious, using simplistic techniques like paint dripping and using Q-tips. Brooks' commentary, too, was performed without a script, so much so that it took Pintoff over a year to fully edit his vocal track down to fit the animation. Quote:

I mumbled whatever I felt that that old guy would have mumbled, trying to find a plot in this maze of abstractions.

This freewheeling, improvisational style of creation and comedy could have easily fallen flat, but the combination of the stuffy, self-serious visuals and musical accompaniment and the witheringly blithe commentary of the elderly Russian Jew is legitimately, consistently hilarious throughout the short's runtime.

"Oh, I know what it is. It's garbage, that's what it is."

The Critic is amusing not only for its snappy wit but for its ruthless willingness to turn the lens of that humour towards itself; the entire short can be seen as a sly parody of abstract art in of itself, of our nature as artists to yearn to see meaning in places where there may not be any at all, and how often those lofty ideals of creating something more meaningful actually creates a widening gap between the author and the audience, an audience who are often just looking for some small entertainment in a mundane world, not to be intellectually challenged or spoken down to.

"Look out! ...too late, it's dead already."

Others, too, must have felt as I did watching the short, as it was very successful. Originally debuting on May 20th, 1963, it was screened at New York City's Sutton Theater on Manhattan's East Side. Shown alongside the popular British comedy film Heavens Above!, the film was well regarded as a tongue-in-cheek mockery of the "pseudo-art film". The short was so successful it won a number of accolades, including the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film and the BAFTA Award for Best Animated Film.

"Lips."

The Critic's influence wouldn't end there, however, as it has been stated by Kevin Murphy, writer and the voice of Tom Servo on Mystery Science Theatre 3000 that the short was what introduced him to the concept of "riffing", doing live or scripted comedic reactions to bad or frustrating media in order to regain some control over the experience they have paid for, to gain some semblance of enjoyment out of an otherwise unpleasant experience.

Overall, I was delighted to discover The Critic. As an artist, I am fully aware of the fact that myself and my peers are fully capable of taking ourselves far too seriously, and it often takes sharp elbow to the ribs such as this to prompt you to reexamine your place in the world. It's almost never a bad idea to have a laugh at things, no matter how important they may seem to you, ESPECIALLY so if it's something you've created yourself.

References:

https://animationobsessive.substack.com/p/animation-at-its-most-pretentious

http://cinema4celbloc.blogspot.com/2016/01/the-critic-1963.html

https://d2rights.blogspot.com/2015/09/the-critic-1963.html

https://drgrobsanimationreview.com/2024/11/11/the-critic/

https://laughingsquid.com/mel-brooks-the-critic-1963/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rooty Toot Toot - 1951, Dir. Jon Hubley

As I discussed in my previous post examining the interviews by Don Peri with Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, during the 1940's the Walt Disney Productions studio underwent a serious restructuring of goals and methods of animation. Following a contentious change in direction from a studio that was largely concerned with creating new kinds of entertainment through artistic experimentation, Disney began to focus more on consistently producing a more refined, realistic style of animation that would supposedly be more accessible to the average viewer. This coincided with the 1941 Disney Animator's strike, which by and large was concerned with uneven pay and practices at the studio which was a non-unionized workplace (although this was contested by Thomas and Johnston who believed there to be communistic ideals behind the strike). In retaliation to this strike (in addition to more underhanded tactics like allegedly hiring goons to break up picket lines and testifying against strikers in anti-communist hearings) Disney fired many of the animators, and although he was eventually pressured into allowing some of them to return by the Screen Cartoonist's Guild, others were disillusioned with the studio and instead left to pursue their own projects. The most notable of these is likely the highly influential independent studio known as the United Productions of America, or simply UPA.

UPA logo, Alvin Lustig, 1947

UPA became known for its extremely stylized, exaggerated and sparse style. Intentionally stepping away from the standard "funny animal" characters that were at that time very common in animation, especially in Disney productions, UPA often instead focused on caricatures of humans that could be animated relatively quickly and cheaply in its limited animation style, similarly to another one of my previous posts, The Dover Boys. Although they were producing shorts as early as 1944, the studio's main animated successes were the series based around Mr. Magoo, a short-sighted elderly curmudgeon who repeatedly avoids certain death by sheer luck, and the popular theatrical short Gerald McBoing-Boing, a young boy who can only communicate in sound effects, the original story of which the short was based upon being written by Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss.

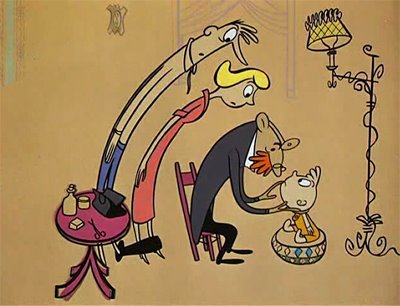

A screenshot of Gerald McBoing-Boing, featuring UPA's stylized human characters and sparse background art.

John Hubley, although not a founder of UPA, was one of its earliest employees and like many others of his ilk, was a former Disney artist who, while supposedly one of the better paid of the strikers, still felt limited by the artistic restrictions of Disney's mandates for realism. Despite the successes the studio had experienced so far, there allegedly existed a fair bit of animosity between the key artists working in UPA. Gerald McBoing-Boing won the studio an Academy award, and Hubley was eager to create a film that was equally influential. This led to the creation of UPA's most expensive and artistically ambitious cartoon yet, 1951's Rooty Toot Toot.

Poster for Rooty Toot Toot.

The short exudes a film noire vibe, its story being a retelling of a now over a century-old tune, Frankie and Johnny. A classic American murder ballad, the song details the murder of an unfaithful pianist by his jilted lover, and the film follows the song very faithfully. The story is presented as a musical courtroom drama, with the testimony of witnesses during the trial of Frankie as flashbacks to the events of the murder. Rooty Toot Toot is notable in animation for the time for the use of adult themes such as sex, violence, corruption, infidelity and ultimately, murder. Although these concepts were not unknown to the animation scene at this point (Fleischer cartoons, for example, often featured some of these concepts) it was still considered quite shocking for the time and as a result, Rooty Toot Toot was withheld from TV syndication for many years.

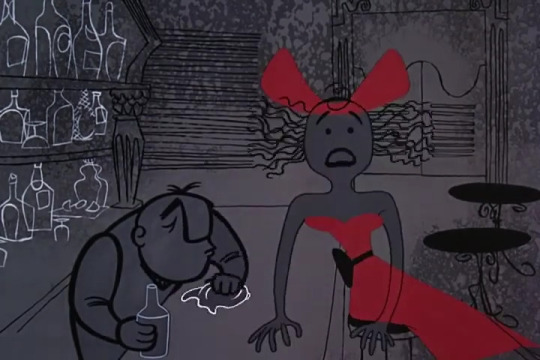

A screenshot of Rooty Toot Toot, featuring the short's highly exaggerated style and use of colour.

What really strikes me upon watching the short, however, is its unique art style. Even by UPA standards, Rooty Toot Toot is unique and experimental. Animated by, among others, Art Babbitt, the original creator of Goofy, and Grim Natwick, animator on Betty Boop for the Fleischer Brothers, the film oozes a Jazzy personality that really adds to the darkly comedic tone. Great care has been given to help establish personality through animation acting in almost every scene. Characters pirouette through their choreography in ballet-like motions (referenced, but not rotoscoped, from poses by dancer Olga Lunick), the put-upon bartender hunches with the weight of the cruel world on his shoulders, Frankie's sweet expressions are quickly replaced by barely-contained fury.

The backgrounds, made by Paul Julian, were created by taking a corroded gelatin roller to produced the distressed look of the dingy, sleazy setting. One thing that strikes me as particularly interesting; characters are often portrayed as "transparent", the bright colours of their garments or the background bleeding through their limbs in an almost cubist or modernist style. The linework is simplistic but clean and clear, and the strong posing really helps characterize the less-than-moral personalities of the story. I think overall it is not unreasonable to say that Rooty Toot Toot was the artistic peak of UPA's catalogue.

Frankie shooting down her attorney.

Unfortunately, not unlike Fantasia, Disney's own ambitious artistry-driven film, Rooty Toot Toot was not the smash success that Hubley had hoped for. Although it did receive an Academy award nomination, it would lose out to The Two Mouseketeers, a Tom and Jerry short. Worse still, not long after its release, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was informed that many of the artists working at UPA were communist sympathizers. Columbia sent a letter to UPA threatening to end the studio's distribution unless the named artists, including John Hubley, publicly denounced communism, and upon his refusal, Hubley was fired from UPA. From that point on the studio floundered and its artistic ambitions, despite its original attempt to distance itself from Disney, ultimately winnowed in the same way Disney's had after the failure of Fantasia.

Today, the short is widely acclaimed as one of the most important pieces of independent animation from an American studio ever made. It was voted as one of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of All Time by industry professionals in 1994, and it is still used as a point of reference for animators for posing and personality. Even now, younger generations of artists are still taking inspiration from this extremely unique and engaging piece, over 80 years later.

References:

http://amodernist.blogspot.com/2012/06/rooty-toot-toot-1951.html

https://www.skwigly.co.uk/100-greatest-animated-shorts-rooty-toot-toot-john-hubley/

https://reedart.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/rooty-toot-toot-1951-upa-studios/

https://www.beyondeasy.net/2017/04/animation-april-rooty-toot-toot-1951.html

0 notes

Text

Working with Disney Report

Reading the book Working With Disney by Don Peri, I must admit to a measure of disappointment; somehow I had imagined the animators revealing deeply hidden, tantalizing secrets and suppressed animosities, struggles that they had faced during their time with the legendary animation giant. Through the weight of his influence, it's hard not to picture Walter Elias Disney (1901-1966) as a domineering tyrant whose shrewd planning and occasionally cutthroat tactics led to him becoming both famous and infamous. However, through my selected interviews with Frank Thomas (1912-2004) and Ollie Johnston (1912-2008), their accounts paint Disney as a soft-spoken man who, while keenly aware of the fine tuned economical planning required by operating a business like Walt Disney Productions (as it was known from 1929-1986), was also very interested in the artistic inspiration that drove many animators of note to pursue working there, producing some of the most memorable animated films of all time. That said, this more artistic aspect of Disney would diminish somewhat as he aged, likely due to a number of factors including the 1941 Disney animator's strike, the financial failures of experimental animated films such as Pinocchio and Fantasia, and his general interest in expanding his company's influence from a simple production studio it began as in the early 1920's to the massive, global powerhouse it has become today.

I chose Thomas and Johnston primarily because of their membership in what was known as "Disney's Nine Old Men", a prestigious group of animators who formed the core of Disney's animated feature films. Although my personal favourite animator of the group, Milt Kahl, was not interviewed by the author, my belief was that through understanding the most elite inner circle of Disney's animators I might gain a better understanding of the studio's inner workings. I suppose it was a bit much to expect their darkest secrets being unearthed, but what I discovered was still illuminating and helped paint a picture of the Walt Disney Corporation's path from the heyday of the Nine Old Men to its current incarnation, where animation seems to be treated as less of a boundary-pushing artform and more as an asset to be used for monetary gain.

Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas was born in Santa Monica, California in 1913 and grew up in Fresno. Originally training to become an industrial designer at Stanford University, later studying Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, he met my other selected interviewee, Ollie Johnston, with whom he became lifelong friends. He began working at Disney in September 24th, 1934, and began as the 224th employee at the studio, assigned to work on the short Mickey's Elephant.

His first work on an animated feature was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, where his animations of the Dwarfs' grief over Snow White's supposed corpse was a breakthrough in terms of animation acting, bringing audiences to tears. He worked at Disney for over 45 years and contributed to nearly every animated feature during that time including Pinocchio, Bambi, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, 101 Dalmatians (1961), The Sword in the Stone (1963), Mary Poppins, The Jungle Book (1967), The Rescuers (1977), and The Fox and the Hound (1981). He was particularly admired for his skill in creating emotionally evocative scenes.

His initial impression of Disney himself was fairly limited; a simple employer-employee relationship, although a fairly pleasant one by all accounts. It wasn't until later that he began to understand his ethos, his desire to "never do the same thing twice" in animation, to push the boundaries of what it could accomplish. However, this attempt to exceed the limits of other artistic mediums would ultimately become unrealistic to maintain, and the audacious musical anthology film Fantasia (1940) simply became too costly and difficult to produce given that at the time, World War II was becoming too influential for a film like Fantasia to really be financially successful, failing to pay off dividends to those risky techniques. Thomas stated that while many of the artists and animators of the studio wanted to continue pursuing the lofty goals of a film like Fantasia, from that point onwards Disney became reticent to take further risks with the studio's films. Rather, he looked for solid premises with extremely refined, appealing animation that would engender a more predictable audience response. Thomas laments in the interview the loss of the more experimental techniques used on Fantasia. Quote:

We see broken, rusted equipment out here in back. “What was that?” Someone says, “Oh, I think they used that as a tub to wash something or other. They had some kind of acid in there.” “What’d you use it for?” “Oh, I don’t know. I can’t remember.” We see results on the film. We say, “Now, this is what we want to do in this sequence here.” A guy says, “Well, the fellows who did that are all gone. I don’t know how you do it.” So it’s hard. You lose the technique unless you’re going to be using it.

On the topic of the 1941 Disney animator's strike, Thomas had little to say that is particularly substantive and is clearly guarded with his responses. Whatever issues he may have had with Disney's leadership, he clearly believed the man was a caring, fatherly figure that had what was best in mind for his employees. He also seems to strongly believe that the political forces organizing the strike were Communist in nature, stating that the members of the union were being "controlled" and "duped". He alludes to the bruised egos of many of the animators at the studios, that uneven pay and privileges of more senior or respected animators led to social unrest being preyed upon by outside forces.

Ultimately, however contentious Thomas may have found elements of Walt Disney, he states emphatically that he would not have changed him as a person, and that his methods lead to dizzying highs as well as the crashing lows. It is clear that working at Disney during its "Golden Age" was a thrilling and artistically invigorating environment, and he reminisces fondly on the cooperative workspace he and the other animators shared in the brief window of time before the war where the possibilities of the studio seemed limitless.

Ollie Johnston

Ollie Johnston was born on October 31st, 1912 in Palo Alto, California. Like his lifelong friend Frank Thomas, he attended Stanford University and later the Chouinard Art Institute in LA, which would eventually be merged by Disney with the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music to become California Institute of the Arts. After following Thomas to work at Disney where he was trained in animation by Freddy Moore, he continued to animate and eventually direct at Disney for a staggering 47 years. His credits include Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi, Song of the South, Cinderella, Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, 101 Dalmatians, The Jungle Book, Robin Hood (1973), The Aristocats (1970), and The Rescuers.

While attending Chouinard, Johnston made connections from students who had been employed by Disney and eventually managed to snag a "tryout", drawing inbetweens of the Three Little Pigs on a strictly timed basis. As an assistant, he had little interaction with Disney himself but as he was brought on to work on Snow White, became privy to the more restricted story meetings. He states that working at Disney during the 1930's was ideal because at that point, the studio had not ballooned to its later size. Animators had direct contact with Disney, who at that time, while often scathingly critical of any work presented to him, was thoroughly enthused with animation in all its forms and was committed to creating the best possible artistic product. However, following the completion of Bambi and the onset of the Second World War, an abrupt change hit the studio and the experimental, art-first mindset was quickly replaced with a steady, refinement-based workflow. Johnston even remarks that it was unclear at first if Disney wouldn't sell the studio. He further states that it was challenging working in this "new" era of Disney, as it was more difficult to have animation okayed for production by the increasingly elusive studio head, as he was distracted by the ongoing creation of Disneyland and the production of television programs endorsing it.

Though he likely did not know it at the time, Johnston shared a critical interest that allowed him to become greatly endeared to Disney: his love of locomotives. Growing up poor in Marceline, Missouri, Disney had few free opportunities for entertainment, and this combined with his uncle being an engineer on Santa Fe's accommodation train line led to him quickly becoming enraptured by the power and majesty of these thundering machines. Johnston, too, had been long a fan of the locomotive and when it was revealed that he had been building a backyard railroad, it lead to Disney and Johnston spending time with eachother outside of work hours. Johnston describes Disney as less guarded and more relaxed in his off time, sharing his financial concerns about the future of the studio and the creation of Disneyland.

On the topic of the strike, Johnston, like Thomas, at first deflects the question somewhat; he instead offers an anecdote on a coffee shop on the studio's premises that was closed down by Disney after he found one too many employees lollygagging, while the exclusive "Penthouse Club" remained open, barred to entry to those below a specific salary, pointing this out as a moment of contention. He then reflects on the strike as an understandably challenging time, passing by picketers on his way into the studio, seeing friendships and relationships ended over the conflict. Also like Thomas, he believes that Disney was strongly concerned with the well being of his employees, and that the union's involvement with the "Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators, and Paperhangers of America", allegedly a Communist organization, led to it taking the wrong approach.

Both Thomas and Johnston seem to have little in the way of a sense of superiority about animation; both remark as having enjoyed their contemporaries such as Warner Brothers cartoons, but do seem to aim for a higher goal of creation than those primarily slapstick-focused shorts. During the interview, Johnston mulls on the fall of the ambitious Fantasia:

How it ever got made, really? I remember Walt back in the late 1940s; I was up in his office with some friends of mine that had the railroad hobby that he knew. We got to talking about Fantasia, and Walt was saying, “God, we could never make another one like that.” You don’t have the staff any more, and you couldn’t afford to make it.

Overall, the two interviews paint a picture of a brief, idyllic window of time where creativity and economics worked hand in hand to make a staggering impact in the burgeoning animation industry, one where innovative techniques and styles were welcomed and artists were challenged to be their absolute best, leading to some of the most iconic animated films ever made. This era, however, was short-lived, and eventually the crushing reality of the monetary necessities that kept the studio afloat while many others sunk tipped the scales towards a business-first mindset that would come to define the Disney company for the rest of its existence.

References:

Working with Disney: Interviews with Animators, Producers, and Artists - Don Peri, 2011

0 notes

Text

The Dover Boys at Pimento University; or, The Rivals of Roquefort Hall (1942) - Dir. Chuck Jones

In recent years, the cartoon most commonly known as The Dover Boys has reached a level of popularity that is fairly unusual for a cartoon from over 80 years ago, becoming a fairly well-known meme and even receiving a lavishly produced fan re-animation. I think in no small part this is due not only because of its release into the public domain, but for its irreverence, its unique animation style and of course, the patented hollering of Mel Blanc's vocal styling.

The Dover Boys parodies the now long defunct "Rover Boys" series of youth novels, a series of books written by Edward Stratemeyer under the pseudonym Arthur M. Winfield. Similarly to the short, the books feature three young students of a military boarding school as they cause pranks and mischief for authorities and criminals alike. Though long since passed from public awareness now, the Rover Boys books sold over a million copies and left an indelible mark on American pop culture at the time.

Despite its recent popularity, information on the production of The Dover Boys is surprisingly hard to find these days, likely due to the fact that it was produced fairly quickly and cheaply. Allegedly, Chuck Jones was expected to produce 10 cartoons a year and had "run out" of good ideas by the end of 1942. Thus, The Dover Boys was animated in order to be made as efficiently as possible, most notably through the use of an animation technique called "smear frames".

In order to "cheat" the effect of a rapid movement of a character, simulating motion blur in a real camera shot, characters were smeared between key poses to make pose to pose animation seem more lively and snappy, utilized in this cartoon through dry-brushing. Although this technique existed in cartoons in the 1930s, The Dover Boys was the first cartoon which used it so notably and frequently. This, combined with other cost cutting measures such as long panning shots of the stylized painted backgrounds by uncredited artist Gene Fleury with no visible characters, and the "sweet Dora Standpipe", the Dover Boys' supposedly dainty object of affection, whose slim-fitting dress causes her to glide comically through her scenes, conveniently not requiring expensive-to-animate walk cycles. This reduced style is now known as "limited animation", and while controversial at the time is now widely utilized by most modern animated productions to help reduce costly animation budgets.

My personal favourite aspect of the cartoon, however, is its preposterous and hilariously animated villain: Dan Backslide, described by the unctuous narrator as a "coward, bully, cad and thief". Visually based on Warner Bros animator Ken Harris, his wiry frame, slicked hair, effeminate cigarette holder and inexplicably green skin make every scene he is in a delight to behold. It may also be my absolute favourite Mel Blanc performance in all of Looney Tunes history, and considering the breadth of the man's career that's really saying something. There's just something about the particular cadence of his screams that put me in hysterics every time.

youtube

However, reaction to the cartoon at the time was slightly less glowing than modern views. According to Jones, Warner Bros. studio executives were displeased with his innovative animation techniques, stating "They hated it, and if they hadn't been block-booking theatres, they would have withheld it and thrown me out." Their attempts to fire him were curtailed, however, by a labour shortage stemming from the ongoing war at the time, and so Jones continued directing for Warner Bros until 1962.

In modern years, The Dover Boys is regarded as being hugely influential for its unique, stylized look and innovative animation techniques, and it was included in the 50 Greatest Cartoons of All Time. Rediscovered by a younger generation after it was released into the public domain through the internet, it quickly became a brief online sensation for its bizarre non-sequitur humour and rapid-fire pacing. In 2018, a collaboration of independent animators reanimated the entire cartoon as a celebration of its 76th Anniversary. Though viewed as a relatively disposable parody at the time, it has since gone on to long outlive the subject of its mockery.

Sources:

The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals - Jerry Black

Frame by Frame: A Materialist Aesthetics of Animated Cartoons - Hannah Frank

http://likelylooneymostlymerrie.blogspot.com/2015/08/383-dover-boys-at-pimento-university.html

0 notes

Text

Silly Symphonies - The Three Little Pigs 1933 - Dir. Burt Gillett

The 36th in Disney's Silly Symphony series, Three Little Pigs was one their most successful productions so far, to the point where it is today considered one of the best-received animated shorts of all time, likely due in no small part to its release during the Great Depression.

Cover from the Comic Adaptation of Three Little Pigs

Though not the first Silly Symphony to be filmed in colour, that being 1932's Flowers and Trees, the Disney studio at this point had cornered the market on coloured animation by making a 5-year deal with the Technicolor Production company. Technicolor's process by this point used a "three strip" process; their specialty camera exposed three strips of black and white film, each attuned to a different colour of the spectrum. This allowed them to produce a broad range of colour, far more effective than their previous methods, and this lively use of colour likely contributed to the short's success during a depression.

This use of colour helped to distinguish the personalities of the Three Little Pigs through their costuming. However, the short was primarily well received for its animation acting; the pigs were strongly characterized through posture and movement. As stated by Chuck Jones, "That was the first time that anybody ever brought characters to life. They were three characters who looked alike and acted differently." This is likely due to the Disney studio's implementation of a story department, a relative rarity for animated productions at the time, employing storyboard artists to fully plan out important plot and character beats during pre-production.

Dorothy Compton, Mary Moder and Pinto Colvig recording "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", Frank Churchill on instruments

The short is a mostly faithful adaptation of the classical (dating before 1840) fable, but is notable for a few major exceptions. The first is the original song produced for the film, "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?", composed by Disney collaborator Frank Churchill. The song was Disney's first hit song, becoming exceptionally popular and providing an upbeat tune to aid the dour mood during the crushing economic depression of the 30s. The titular Wolf, voiced in the short by comedian Billy Bletcher, became emblematic of the depression itself, and later even Adolf Hitler with the advent of the second world war.

The second notable exception is more unfortunate. Similarly to the Mickey Mouse short I mentioned in my last journal, The Opry House, Three Little Pigs involves a staggeringly misguided portrayal of a Jewish stereotype, with the Wolf disguising himself as a "peddler" in order to try to wheedle his way into one of the pig's homes, complete with a thick Hebrew accent and Yiddish music accompaniment. Even for the time in which it was released, this was considered in poor taste and the Rabbi JX Cohen, leader of the American Jewish Congress wrote his displeasure to Disney, calling the film "vile, revolting and unnecessary as to constitute as direct affront on Jews". Later re-releases of the short would heavily censor this scene, as seen above. Still, these hateful elements are shocking compared to its otherwise light and comical tone.

In spite of this, however, Three Little Pigs was remarkably successful with audiences. It premiered at the Radio City Music Hall in New York City on May 25th 1933, before the First National Pictures film Elmer, the Great, and continued to have an extensive run in theatres following this, with its promotions on theatre marquees often above the films it preceded, a rarity with animated shorts. The surprising popularity of the short led to a rush of merchandising, including storybooks, figurines, soap, and countless others. It also inspired many animators, including the aforementioned Chuck Jones as well as Ward Kimball, Milt Kahl and Marc Davis. Pigs even took home an Academy Award for Best Animated Short.

Today, the film is still fairly well regarded, although considered a fairly experimental turn for the fledgling Disney studio and marred somewhat by its original uncensored antisemitism. In 1994 it was voted Number 11 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time by professionals in the animation field, and in 2007 was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress in the US National Film Registry for its "cultural, historical, or aesthetic significance". Today on Disney+, only its censored re-release version can be seen, and one must search elsewhere for its original misguided racial humour.

References: https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/walt-disneys-three-little-pigs-1933/

https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/big-bad-blockbuster-the-90th-anniversary-of-disneys-three-little-pigs/

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2003/cteq/3_little_pigs/

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Skeleton Dance (1929) - Directed by Walt Disney

Imagery of the dead dancing is not a new concept; artistic images of corpses and cadavers cavorting to their graves has been common since the Late Middle Ages (1300-1500). Simultaneously horrifying and comedic, it has long been a method for artists to contend with the grim inevitability of death, while acknowledging the humour in its unification of people of all stripes. No matter how they struggle, the king and the pauper will ultimately find themselves in the same place - the grave.

Danse Macabre, Painted by John of Kastav, finished in 1490, Church of the Holy Trinity in Hrastovlje, Slovenia

The first of Disney's experimental Merry Melodies series and one of the most beloved of their early run of animations, The Skeleton Dance has continued to be enjoyed almost 100 years after its creation in 1929. Though not explicitly based around Halloween, it is frequently revisited in October for its dark, mischievous tone. As well, its imagery, though slightly ghoulish, has aged remarkably well as compared to its contemporaries of the time, such as another Disney short animated and recorded concurrently to Skeleton Dance, The Opry House (1929), which featured elements that would be considered xenophobic and transphobic today.

The concept of an animated short choreographed to prerecorded music was originally pitched by longtime Disney collaborator and acquaintance Carl W. Stalling, and supposedly led to some consternation between the two otherwise friends. At the time, most musical accompaniment of film or animations would be produced following completion of the visual aspect. This lead to the development of an early prototype of something known as a "click track", a metronome-like series of audio cues to help synchronize music to a visual element. This early method involved punching holes in a roll of undeveloped film, that when run on the soundhead would produce a series of clicks and pops to guide the animators. The soundtrack for Skeleton Dance was recorded in the Cinephone studios in New York under Pat Powers, Disney's short-lived distributor.

The Skeleton of Death Comes for the Bishop in the Abbey, Lithograph by Thomas Rowlandson, Undated.

Animator Ub Iwerks was supposedly inspired by drawings of skeletons by British cartoonist Thomas Rowlandson and imagery from the walls of Etruscan tombs. Animation on Skeleton Dance began in January of 1929 and took almost 6 weeks to complete, of which Iwerks animated all but the first scene, which was animated by Les Clarke.

Aside from the titular boneheads, the animation features many horror tropes - a cold, ominous wind blows throughout the film, an owl leers at the camera, silhouetted by the moon, ragged black cats hiss and spit at each other perched upon gravestones, bats flutter and spiders scurry.

It's not hard to see why this film has become closely associated with Halloween despite being completed nearly 7 months away from the holiday. Although America's devastating economic downturn would not begin in earnest until September of '29 following the Wall Street Crash, it's easy to draw parallels to the untold loss of life due to starvation and sickness during the Great Depression and the emaciated stars of Skeleton Dance, not wholly unlike the Danse Macabre of the victims of the Black Death in the mid 1300s.

Reactions to The Skeleton Dance were unsurprisingly mixed. It was originally previewed on March 20th to a lukewarm response, then screened at the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles, Fox Theatre in San Francisco, and the Roxy Theatre in New York. Pat Powers, Disney's then-distributor, upon receiving negative reactions from exhibitors displeased by the short's morbid tone, allegedly returned a note to Disney: "They don't want this. MORE MICE." Skeleton Dance was allegedly even banned in the country of Denmark for its morbidity, judged to be unsuitable for children.

However, not all reception was negative. Many lauded the film, such as an article from Variety that stated "Title tells the story, but not the number of laughs included in this sounded cartoon short. The number is high." Another article from The Film Daily called it "a howl from start to finish". In 1994, it was voted 18th of the 50 Greatest Cartoons ever made by industry professionals. These days, The Skeleton Dance is regarded as a masterpiece of classical animation and is considered highly influential as one of the first films to feature highly synchronized visuals and audio.

References:

https://www.thedisneyclassics.com/blog/the-skeleton-dance

https://mouseplanet.com/the-skeleton-dance-story/7655/

https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/the-spooky-story-of-the-skeleton-dance/

https://www.wdw-magazine.com/today-in-disney-history-the-skeleton-dance-debuted/

https://screenrant.com/disney-horror-movie-banned-too-dark-skeleton-dance/

https://archive.org/details/variety96-1929-07/page/n203/mode/2up

0 notes

Text

Hi, I'm Albert Guest and this is my blog. I am a lifelong artist, and I've been interested in animation since I was a kid but only recently have I been working towards becoming an animator myself. I find you can express so much character and personality through animation, not to mention portray things that live action or CG don't convey as appealingly.

Some of my inspirations include:

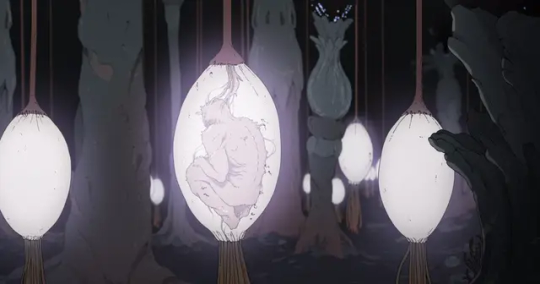

Primal

Scavenger's Reign

And of course, Smiling Friends :)

0 notes