Photo

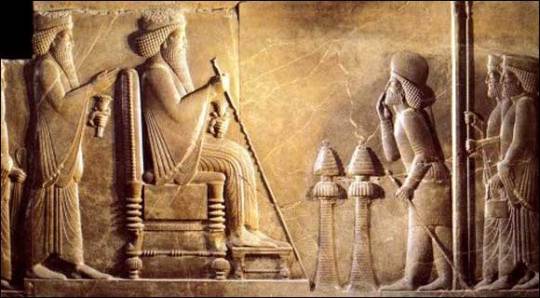

Xerxes I of Persia (Xerxes meaning “ruling over heroes”), also known as Xerxes the Great (519 BC-465 BC), was the fourth king of the Achaemenid Empire.

When Darius I of Persia died in October 486 BC Artabazanes claimed the crown as the eldest of all the children, because it was an established custom all over the world for the eldest to have the pre-eminence; while Xerxes, on the other hand, urged that he was sprung from Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that it was Cyrus who had won the Persians their freedom. Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes to be a result of his consideration of the unique positions that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa have had. Artobazan was born to “Darius the subject”, while Xerxes was the eldest son born in the purple (meaning “born during his parents reign”) after Darius’s rise to the throne, and Artobazan’s mother was a commoner while Xerxes’s mother was the daughter of the founder of the empire.

Xerxes was crowned and succeeded his father in October–December 486 BC when he was about 36 years old. The transition of power to Xerxes was smooth due again in part to the great authority of Atossa and his accession of royal power was not challenged by any person at court or in the Achaemenian family, or any subject nation.

Almost immediately, he suppressed the revolts in Egypt and Babylon that had broken out the year before, and appointed his brother Achaemenes as governor or satrap (Old Persian: khshathrapavan) over Egypt. In 484 BC, he outraged the Babylonians by violently confiscating and melting down the golden statue of Bel (Marduk, Merodach), the hands of which the rightful king of Babylon had to clasp each New Year’s Day. This sacrilege led the Babylonians to rebel in 484 BC and 482 BC, so that in contemporary Babylonian documents, Xerxes refused his father’s title of King of Babylon, being named rather as King of Persia and Media, Great King, King of Kings (Shahanshah) and King of Nations (i.e. of the world).

Darius died while in the process of preparing a second army to invade the Greek mainland, leaving to his son the task of punishing the Athenians, Naxians, and Eretrians for their interference in the Ionian Revolt, the burning of Sardis and their victory over the Persians at Marathon. From 483 BC Xerxes prepared his expedition: A channel was dug through the isthmus of the peninsula of Mount Athos, provisions were stored in the stations on the road through Thrace, two pontoon bridges later known as Xerxes’s Pontoon Bridges were built across the Hellespont. Soldiers of many nationalities served in the armies of Xerxes, including the Assyrians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Egyptians and Jews.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Xerxes’s first attempt to bridge the Hellespont ended in failure when a storm destroyed the flax and papyrus cables of the bridges; Xerxes ordered the Hellespont (the strait itself) whipped three hundred times and had fetters thrown into the water. Xerxes’s second attempt to bridge the Hellespont was successful. Xerxes concluded an alliance with Carthage, and thus deprived Greece of the support of the powerful monarchs of Syracuse and Agrigentum. Many smaller Greek states, moreover, took the side of the Persians, especially Thessaly, Thebes and Argos. Xerxes was victorious during the initial battles.

Xerxes set out in the spring of 480 BC from Sardis with a fleet and army which Herodotus estimated was roughly one million strong along with 10,000 elite warriors named the Persian Immortals. More recent estimates place the Persian force at around 60,000 combatants, although this is disputed: another modern estimate of the Persian invasion force is roughly 500,000, with the Persian Empire controlling forty percent of the world’s population, more than 100 million people, at that time.

At the Battle of Thermopylae, a small force of Greek warriors led by King Leonidas of Sparta resisted the much larger Persian forces, but were ultimately defeated. According to Herodotus, the Persians broke the Spartan phalanx after a Greek man called Ephialtes betrayed his country by telling the Persians of another pass around the mountains. After Thermopylae, Athens was captured and the Athenians and Spartans were driven back to their last line of defense at the Isthmus of Corinth and in the Saronic Gulf.

What happened next is a matter of some controversy. According to Herodotus, upon encountering the deserted city, in an uncharacteristic fit of rage particularly for Persian kings, Xerxes had Athens burned. He almost immediately regretted this action and ordered it rebuilt the very next day. However, Persian scholars dispute this view as pan-Hellenic propaganda, arguing that Sparta, not Athens, was Xerxes’s main foe in his Greek campaigns, and that Xerxes would have had nothing to gain by destroying a major center of trade and commerce like Athens once he had already captured it.

At that time, anti-Persian sentiment was high among many mainland Greeks, and the rumor that Xerxes had destroyed the city was a popular one, though it is equally likely the fire was started by accident as the Athenians were frantically fleeing the scene in pandemonium, or that it was an act of “scorched earth” warfare to deprive Xerxes’s army of the spoils of the city.

At Artemisium, large storms had destroyed ships from the Greek side and so the battle stopped prematurely as the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated. Xerxes was induced by the message of Themistocles (against the advice of Artemisia of Halicarnassus) to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, rather than sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armies. The Battle of Salamis (September, 480 BC) was won by the Greek fleet, after which Xerxes set up a winter camp in Thessaly.

Due to unrest in Babylon, Xerxes was forced to send his army home to prevent a revolt, leaving behind an army in Greece under Mardonius, who was defeated the following year at Plataea. The Greeks also attacked and burned the remaining Persian fleet anchored at Mycale. This cut off the Persians from the supplies they needed to sustain their massive army, and they had no choice but to retreat. Their withdrawal roused the Greek city-states of Asia.

In 465 BC, Xerxes was murdered by Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard and the most powerful official in the Persian court (Hazarapat/commander of thousand). Although Artabanus bore the same name as the famed uncle of Xerxes, a Hyrcanian, his rise to prominence was due to his popularity in religious quarters of the court and harem intrigues. He put his seven sons in key positions and had a plan to dethrone the Achamenids.

In August 465 BC, Artabanus assassinated Xerxes with the help of a eunuch, Aspamitres. Greek historians give contradicting accounts of events. According to Ctesias (in Persica 20), Artabanus then accused the Crown Prince Darius, Xerxes’s eldest son, of the murder and persuaded another of Xerxes’s sons, Artaxerxes, to avenge the patricide by killing Darius.

But according to Aristotle (in Politics 5.1311b), Artabanus killed Darius first and then killed Xerxes. After Artaxerxes discovered the murder he killed Artabanus and his sons. Participating in these intrigues was the general Megabyzus, whose decision to switch sides probably saved the Achamenids from losing their control of the Persian throne.

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

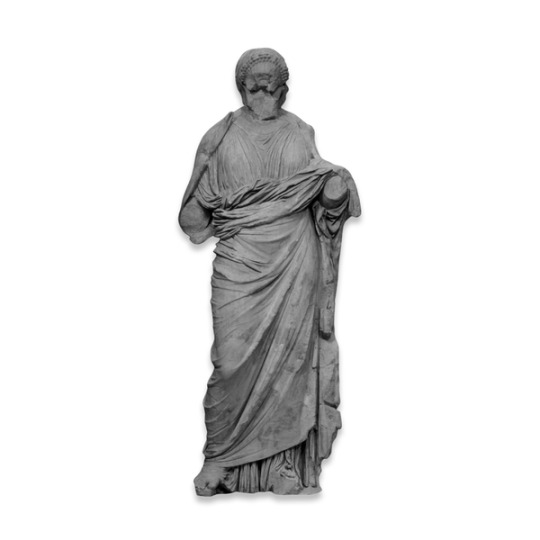

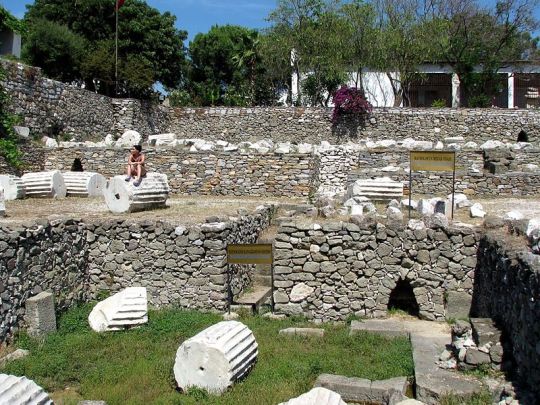

7 Wonders of the World: Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Mausolus was a satrap of the Persian Empire, he married his sister Artemisia II of Caria. He ruled at Halicarnassus for 24 years, expanding his territory to the south-west coast of Antatolia. Though his family originated from Halicarnassus and the surrounding area, Mausolus admired the Greek way of life, spoke Greek and founded several cities of Greek design.

Mausolus built up Halicarnassus to be his capitol city, magnificent and safe from capture. There was a small canal that could easily be defended from warships, his palace was fortified and several walls and watch towers were built. He also had a Greek style temple built to Ares, the Greek god of war. The whole city was embellished in great works of art and gleaming buildings of marble; Mausolus and Artemisia paid for all this with huge amounts of tax money. On a near by hill, overlooking their great city, Artemisia planned a great tomb for her and her husband.

In 353 BC Mausolus died, leaving Artemisia to rule alone. In his honour she decided to build the greatest tomb she could for him and spared no expense. The tomb for Mausolus became so famous that the term “mausoleum” came about as a general for a tomb above ground.The structure was considered such a unique aesthetic triumph that it was included in the lists of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Artemisia put a call out for the greatest artists in Greece to come and build the tomb. It was designed by by the Greek architects Satyros and Pythius of Priene. It stood at nearly 45 meters (148 ft) tall, but it wasn’t it’s size that made it a wonder, it was the high quality statues and sculptural relief that adorned each side. Each side was made by a different Greek sculptor: Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas of Paros (who supervised the building of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, another wonder of the world) and Timotheus.

The Mausoleum was enclosed in a courtyard. The tomb sat on a stone platform, a stairway led up this flanked with stone lions. Along the outer walls of the platform stood many statues of gods and goddesses and on each corner stood a stone warrior on horseback guarding the tomb. The square tomb rose out of the platform covered in bas relief showing action scenes. These included the battle between the Centaurs and the Lapiths (also depicted on the Parthenon metopes), and the battle of the Greeks against the Amazons, a legendary race of warrior women.

The top section of the tomb had thirty six columns, ten per side, with each corner sharing two. Standing between each pair of columns stood a statue. Behind the columns was a great, cella-like, block to support the massive weight of the roof. The rook was pyramidal with 24 steps, on top of which stood a final statue group; a quadriga, a four hourse chariot in which stood images of Mausolus and Artemisia. A stone wheel of this chariot has been found, it measure 2 meters in diameter.

Several reconstructions of the whole structure exist however historians today still debate how the tomb would have looked from the scant evidence from the site and descriptions of ancient authors, particularly Pliny the elder.

Artemisia only lived two years after her husband’s death. Their ashes were placed in the tomb before it was finished. However, according to Pliny the Elder, the craftsmen chose to remain and finish the structure after the deaths of their patron “considering that it was once a memorial of his own fame and of the sculptor’s art.” It was probably destroyed in an earthquake that shook the area between the 12th century (where it was still written about as a wonder) and 1402 when it was recorded as a ruin by the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. The knights used some of the stones from the ruin to build their castle, Bodrum.

(images from British Museum and http://www.livius.org/ha-hd/halicarnassus/halicarnassus_mausoleum.html)

127 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Persian Relief

Limestone

From Persepolis

c.6th-5th century BC

Achaemenid (Persian)

Width: 105 cm

Height: 51 cm

Relief shows guardsmen with spears advancing to the right wearing Persian dress, bracelets and earrings.

Source: British Museum

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gold vessel terminating in a lion’s head. Achaemenid period, 5th century B.C.

This vessel shows great technical skill in its manufacture: it bears the marks of various elements having been joined by brazing, and the lion has been rendered in extreme detail. The ostrich plumes on its side seem to indicate that this is supposed to be a winged lion.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wine Strainer

Found in Iran

6th-4th Century BC

Achaemenid Period

(Source: The British Museum)

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nereid Monument

Lykian, about 390-380 BC

From Xanthos, (modern Günük, south-western Turkey)

The daughters of the sea-deities Nereus and Doris are known as Nereids. Numbering between 50 and 100, they were popular figures in Greek literature. They were believed to be personifications of the waves of the ocean, and benign toward humanity. The best known of the Nereids were Amphitrite, consort of Poseidon (a sea and earthquake god); Thetis, wife of Peleus, king of the Myrmidons, and mother of the hero Achilles; and Galatea.

(Source: The British Museum)

336 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Golden and silver cloak pin in the shape of a lion head.

Most often these pins are made and used as twins. It is 5.3cm in height.

Found in Iran. 400 BC.

Source: Leiden Museum of Antiquities

937 notes

·

View notes

Photo

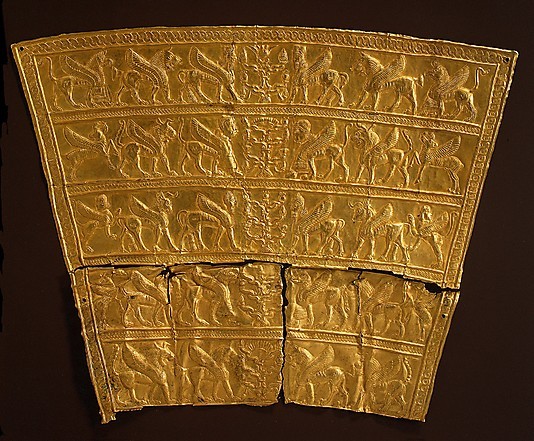

Plaque of Winged Creatures approaching stylised trees

800-700 BC

Iran

Iron Age III

In 1947 a treasure was reputedly found at a mound near the village of Ziwiye in northwestern Iran. Objects attributed to Ziwiye are stylistically similar to Assyrian art of the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. as well as to the art of contemporary Syria, Urartu, and Scythia. Many objects of gold, silver, bronze, ivory, and ceramic have since appeared on the antiquities market with the provenance of Ziwiye, although there is no way to verify this identification.

This plaque, perforated around the edge, was perhaps once attached to a garment of a wealthy lord or to the shroud of a prince. Its design is similar to contemporary art of Assyria, Urartu, and Scythian-style objects. The plaque was originally composed of seven registers decorated in repoussé and chasing; two were separated and are now in the collection of the Archaeological Museum, Tehran. The registers display the familiar composite creatures of the ancient Near East striding in groups of three toward a stylized sacred tree, the central motif. The human-headed, winged lion, seen in the first and third register, is a creature that also appears as a gate guardian on the doorjambs in the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. A sphinx struts along the second band, followed by winged lions and an ibex. The bodies of the fantastic creatures are composed of unusual combinations of animal and bird parts: in the uppermost register, the lions sport ostrich tails, while in the second, their tails are those of scorpions. The trees of life bear pomegranates, pine cones, and lotus flowers. Each scene is framed and separated by a delicate guilloche pattern.

(Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

As more and more people migrated into Rome the migrants took up agriculture and farms and sheep herders took up much of the land.

Source: Traditions and Encounters HIstory Textbook

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Knife and Dagger

c.1050 - 770 BC

Western Zhou Dynasty

(Source: The British Museum)

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persian Royal Road

"The Persian Royal Road stretched a good 1,600 miles from Aegean port of Ephesus to Sardis in Anatolia, through Mesopotamia along the Tigris River, to Susa in Iran, with an extension to Pasargadae and Persepolis."

-T and E Volume I

2 notes

·

View notes

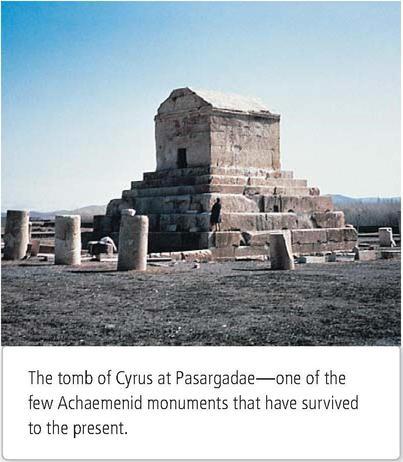

Photo

-Traditions and Encounters Volume I

7 notes

·

View notes

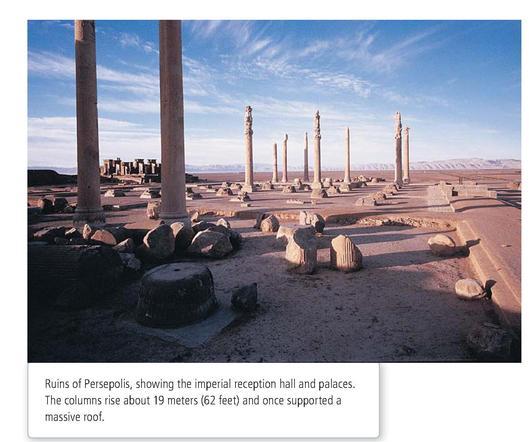

Photo

-Traditions and Encounters Volume I

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Found in Pompeii, Gold coiled snake bracelet.

509 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(x)

Darius standardized coins that made trade possible.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

tumblr_mfgq4rYn0e1rui49ao1_1280.jpg

4 notes

·

View notes

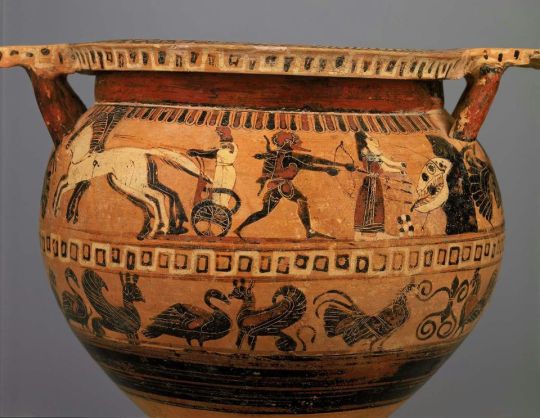

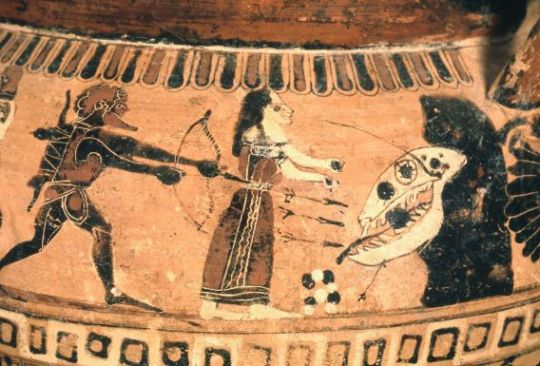

Photo

Krater, ca. 550 BCE. In the detail, Hesione throws rocks at a the head of a dragon-like beast. The artist was possibly inspired by a fossilized dinosaur skull visible in the side of a cliff.

65 notes

·

View notes