I want to ask every woman: When did you leave home? Why did you leave? Do you ever come home to visit? How long do you stay? What would happen if you returned to stay? What would it take for you to come home for good?

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

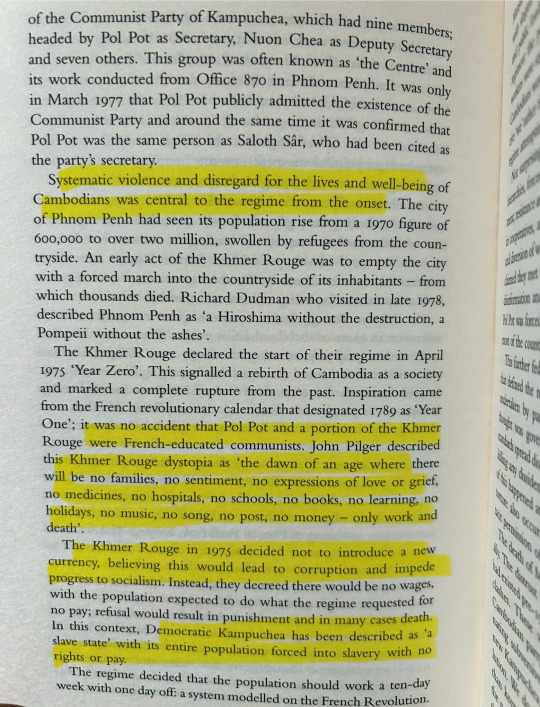

In U.S. high schools, you get 155 hours of Hitler, 3 minutes on Stalin, and zero on Pol Pot.

Fifty years ago Pol Pot’s forces entered the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. This was perhaps the most insanely murderous regime in human history. And this occurred to the cheers and satisfaction of Western leftist intellectuals.

The Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh lost his entire family to the communist takeover and subsequent genocide in Cambodia in the 1970s. His new film, “Meeting With Pol Pot,” dramatizes a real 1978 visit to Cambodia by three Western journalists.

Many spoilers ahead.

At the time, the country was sealed off from the world. After taking power in 1975, the Khmer Rouge communist regime emptied the cities and forcibly relocated the population into labor camps. The film is loosely based on Elizabeth Becker’s 1986 book When the War Was Over.

One of the journalists in the film, Alain Cariou (played by Grégoire Colin), is a socialist academic who, as a young man, studied with Pol Pot in Paris. Both were student activists (shocking!).

Pol Pot grew up relatively well off and learned about Marxism and socialism as a student in France. Despite his family's relatively prosperous origins, in an interview in 1977, Pol Pot claimed that he was born into a "poor, peasant family".

You still see this among affluent socialists today, who cosplay poverty in an attempt to manipulate actual poor people into supporting their twisted ideology.

Later, after the communist takeover in Cambodia, Pol Pot and his boys would line suspected class enemies up against a wall and speak French to them. If they reacted (indicating they understood and were therefore rich/educated) he’d have them shot.

No one hates elites more than elites (or aspirational elites).

Once you understand this, then you understand why you’ll find 100 communists at an Ivy League or Oxbridge institution before locating even 1 at a community college.

Too many people mistakenly think that the battle is between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” What actually happens is the "haves" want to seize money from the "have-mores" and to do so they disguise their malicious desire as concern for the "have-nots."

Relatedly, many people misunderstand that clever intellectuals can be more dangerous than oafish jocks. Didier Maleuvre, a professor of literature at UC Santa Barbara, reminds us that, "large-scale harm is not committed by the frothing bully; it is done by well-mannered, affable, intellectual, and comparatively feminized coalition builders like, say, Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and other such well-spoken technocratic tyrants.”

Anyway. Back to the film. The journalist Cariou, now in his forties, arrives in Cambodia full of optimism. He looks forward to visiting his old friend Pol Pot. He wants to see the revolution up close. He believes the Western press has unfairly maligned it. Never mind the stories from refugees about forced labor, executions, starvation, and torture. Cariou is prepared to believe he’s witnessing the birth of a utopia.

Cariou parrots the regime’s slogans, praises their effort to create “a new man,” and seems genuinely impressed by the society he encounters: peasants stripped of names, possessions, education, and even eyeglasses.

Everything they see, every person they interview, every site they visit is orchestrated and manipulated to present a picture of harmony, equality and prosperity.

Reality gradually becomes harder to ignore. Cariou and his two fellow journalists become increasingly aware of how much coercion, torture, and outright murder is required to build this supposed “utopia.”

Still, Cariou clings to his beliefs. He wants the revolution to work. For Cambodia, of course, but for the ideals he once marched for as a student in Paris. The Khmer Rouge communists repeat slogans about human dignity. But there’s none of it in sight. Even in the Potemkin village the communist officials have orchestrated for the journalists, the sense of emptiness, desperation, and death in the air is unmistakable.

Gradually, you see Cariou move from confidence to unease to guilt. The film director Rithy highlights the painful process of waking up. Of watching a cherished worldview crumble under the weight of reality. Of famine, torture cells, and piles of human skulls.

Interestingly, Cariou is based on real-life British academic Malcolm Caldwell, who was executed under the orders of Pol Pot.

Cariou’s colleagues aren’t so easily manipulated.

Lise Delbo (Irène Jacob), a veteran journalist, covered Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

She approaches the trip with more skepticism and a personal question: what happened to her old interpreter, one of the many Cambodians sent off to labor camps and never heard from again?

The third visitor, Paul Thomas (Cyril Gueï), is a French African war photographer. He’s seen too much to be fooled. He objects when the communist officials try to stage every image and control every interaction the journalists have with the local population.

At one point in the film, Thomas quietly opens one of the neatly arranged sacks of rice—meant to show off the agricultural success of the communist regime—and discovers these sacks are actually filled with dirt.

Most of their visit takes place near the unfinished Kampong Chnnang Airport. The regime started building it in 1976 but never completed it. Thousands of forced laborers died there. Starved, beaten, executed. For years, the place was said to smell of death. Human bones would rise through the soil when the rains came.

There’s a reason Eisenhower instructed that the Nazi concentration camps be thoroughly photographed at the end of World War II. He told U.S. troops to document everything. Eisenhower understood that there would be people in the future who would deny it ever happened because they were naive about the depths of human depravity.

Today, we largely take for granted that murderous regimes can arise out of “hate” or other ugly motives. Many people have a difficult time, though, processing the fact that murderous regimes in the twentieth century also grew out of noble-sounding ideals like “equality,” “egalitarianism,” “human dignity,” and so on. Relatedly, you’ll often hear people accuse their opponents of “dog whistling” to subtly support fascism or far-right extremism. Communists don’t have to dog whistle, because their ideas are not stigmatized to nearly the same degree, despite the fact that communism is the frontrunner among murderous ideologies with regard to body count.

People focus on ingroup/outgroups, how people are cruel to outsiders, how people dehumanize their outgroup, and so on. More interesting to me is how communism got groups to murder their own people. Pol Pot, a Cambodian himself, got other Cambodians to slaughter millions of their fellow citizens. Same with Stalin and Mao. People who look just like you, speak the same language as you, eat the same food as you, practice the same religion, and so on. Still mass slaughter and unrivaled bloodthrist. Educators, psychologists, and formally educated people in general are weirdly uncurious about this.

Eventually, the journalists are granted a meeting with Pol Pot. When the moment arrives, the director Rithy doesn’t show him clearly. We hear a voice (actually Rithy’s voice) speaking from the shadows.

Pol Pot declares, “Better an absence of men than imperfect men.”

The effect is eerie. It reminded me of Colonel Kurtz from “Apocalypse Now” (my discussion/review with Trung Phan and Jim O'Shaughnessy here).

If you want to learn more about the history of what happened in Cambodia, I recommend reading Survival In the Killing Fields by Haing Ngor and The Lost Executioner by Nic Dunlop. You could also watch “First They Killed My Father,” a heartrending film directed by Angelina Jolie, based on the book by Loung Ung.

You’ll learn how Pol Pot directed a reign of terror that led to the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people, or about one-fourth of Cambodia’s population. Pol Pot was only in power from 1976-1979. In less than 4 years, 25% of Cambodia's population was killed. This is widely considered to be a genocide. Naturally, Western intellectuals at the time did all they could to deny what was happening.

Pol Pot and his inner circle of communist revolutionaries tore apart Cambodia in an attempt to ''purify'' the country's society and turn people into revolutionary worker-peasants.

Many people were executed outright: former soldiers, civil servants, merchants, teachers, anyone labeled a “parasite” or “intellectual.” The elderly, the blind, the sick, and even children were tortured and killed.

As his project began to fail and famine swept the country, Pol Pot blamed those around him.

First it was loyalists from the pre-revolutionary regime. Then he blamed other Communist officials. Eventually, he targeted his closest allies.

Suspected enemies were rounded up and sent to prisons, where they were tortured into confessing to imaginary plots. Then after confessing, they would be executed.

This part about communist regimes—the obsession with confessing one’s guilt—has always fascinated me. And it usually plays out the same way. The communists in Maoist China described it as “exhaustive bombardment.”

The interrogator will basically say, “Hey, we already know you are a spy/counter-revolutionary/enemy of the regime. We just need you to say so. And if you acknowledge your guilt, then this will all go so much easier for you.” Eventually, the tortured individual just wants the pain to stop and they acquiesce, believing that if they just confess to the imaginary crimes, they will be released or at least will no longer be tortured. So they confess. And once they have acknowledged their guilt, they are executed.

On this point, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn explained the logic of Soviet interrogation tactics: because guilt can never be absolutely certain, it is useless to seek evidence in the first place. Therefore, evidence is not necessary. Thus, the best proof of guilt is a confession. Which the interrogator must do his utmost to extract.

Communist officials in various regimes were obsessed with extracting confessions from the falsely accused. Why bother with confessions? One purpose is to shatter the idea of objective truth that exists independently of the Party. Another is to force the population to accept falsehood as a way of life. To humiliate ordinary people.

Why did the falsely accused confess? After all, people who are legitimately guilty often deny any wrongdoing. Of course, one reason is to get the torture to stop. And because the interrogator deceives the punished individual by saying “If you just confess, everything will be okay.” The historian Robert Conquest suggested that subjects of a communist regime are so conditioned to tell lies, that telling one more lie in the face of fabricated accusations is no big deal.

Years ago, I visited the Oranienburg concentration camp in Germany. There I learned that Nazi guards needed some kind of "reason" to murder prisoners. They couldn’t just indiscriminately execute people. “Official procedure” was required. This upheld the illusion that this was all somehow “legitimate.”

You can read this description of what happened in Somalia, and it looks no different from how communism worked in just about every other country in which it was implemented:

“I was born in Somalia in 1969. The country had achieved independence nine years before. But less than a month before I was born—on October 21, 1969—a junior member of the brand-new Somali armed forces seized power with the help of the Soviet Union. The first two decades of my life were shaped by the upheaval that followed that coup. The Somalia that gained its independence was a young, optimistic society full of national pride. We had such hope for growth, political stability, prosperity, and peace. But, in a story sadly familiar to many of my fellow Africans, those hopes were dashed. What followed was a nightmare. For me it is all captured in the earliest memories of my youth: statues of Mohamed Siad Barre, our dictator, sprung up across Mogadishu, flanked by a trio of dark seraphim: Marx, Lenin, and Engels. This particular communist experiment plunged Somalia into bloodshed, mass starvation, and a 20-year period of suffocating tyranny. I recall my grandmother and mother smuggling food into our house. I also remember the whispering: we felt the state was omnipresent. It could hear everything. My father was thrown into prison. His friends—those other pioneers in pursuit of a democracy modeled on America—were either jailed like him or, in many cases, executed.”

And yet there are still people who believe in this ideology. You can be a communist in a capitalist society. You can’t be a capitalist in a communist society.

In Cambodia during Pol Pot’s reign, temples were destroyed. Religion was abolished. Buddhist monks were murdered.

Under the banner of communism, the Khmer Rouge regime enslaved and murdered millions of people.

Families in Cambodia were torn apart. Husbands separated from wives, children from parents. Holidays and music were banned. Romance, prayer, joy—all outlawed. Local officials dictated who could marry. Disobedience meant execution. Children were forced to inform on their families.

Many of those who resisted, including children, were buried alive, dropped from balconies, or fed to crocodiles.

Work crews were formed to dig canals and farm land by hand, without machines. People labored from sunrise to late at night. The regime promised progress. Instead it delivered cruelty, hunger, and mass death.

Recall this quote from Thomas Sowell: “The history of the 20th century is full of examples of countries that set out to redistribute wealth and ended up redistributing poverty.” These regimes aimed to promote peace and instead promoted terror and violence.

It’s important to remember here that Pol Pot didn’t rise to power by promising to be evil. He promised goodness. He promised dignity. Fairness. Equality. A better world. He said he wanted to help the poor.

That’s always how it starts.

Neither Pol Pot nor the people who helped him were mustache-twirling villains. They were educated, articulate, and convinced they were on the right side of history. Evil usually doesn’t look like evil. This is the part that’s hard for some people to accept. Many of the worst atrocities of the 20th century weren’t driven by hatred or greed.

The communists in Cambodia turned an entire nation into a prison camp, then a graveyard. And they did this in the name of equality, fairness, dignity, and justice.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Based on weak scientific evidence, many marijuana advocates likewise promised that legal cannabis would lead people to use fewer opioids. Recent reviews, though, suggest that marijuana legalization is more likely to increase than reduce opioid-death rates.

from rob hernderson's newsletter

0 notes

Text

A while back I caught up with a guy from my high school graduating class. After we graduated from high school, he spent a few years floundering in community college. Failed half his classes, smoked a lot of weed in parking lots, hooked up with random girls. This is “John,” for those of you who read my memoir Troubled.

He joined the military at age 23. He said it was tough, but he enjoyed the challenge. Lost a bunch of weight, felt good about himself, and exited with a plan to finish college.

Honorably discharged. Then fell back into old habits. Back to the wake-and-bake life, ditching classes, gained weight. The external pressure was off, and he went back to his old ways. Not quite on the same level as before. Slackers in their 30s can’t compete with their 19-year-old selves at being a delinquent. But he had become roughly the same guy again.

I thought about this while listening to the behavioral geneticist Kathryn Paige Harden on the Sam Harris podcast.

At one point in the conversation, they were discussing the role of IQ in life outcomes. A paraphrased quote from Harden:

“What are we actually aiming for—higher IQs, more education? Or are we aiming for people to be healthy and happy? A society where you don’t need to be especially talented or educated to get decent healthcare and live a good life.”

This is perfectly stated. The chattering classes are obsessed with education. I can’t open a prestige media webpage, liberal or conservative, without seeing at least one headline that has something to do with college or the education system.

Americans are preoccupied with college, so much that more than half of high school graduates enroll in college. Then nearly half of them drop out, often saddled with debt. College is the ticket to a good life, we’re told. Get that degree, land a white-collar job, and happiness awaits.

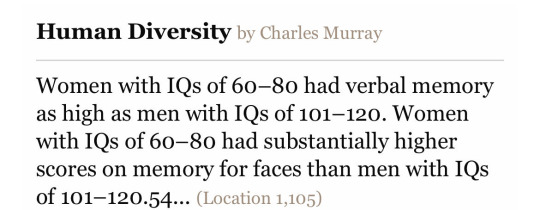

A smaller contingent of people focus more on IQ, and how this, rather than education level, is the more important factor for outcomes like income, marriage, obesity, life expectancy, etc. They point out research showing that education doesn’t seem to have much of an effect on lifting IQ scores.

For example, this study shows that verbal IQ has declined among college graduates since the 1970s. Perhaps because more people are going to college now than in the past. More recently, a recent meta-analysis found that the average intelligence of university students and university graduates has dropped to the average of the general population. Though as I’ve noted before, no one is a prisoner of their IQ.

Either way, we are focused on the wrong thing. Why should college or smarts or conscientiousness be required to live a fulfilling life? [...]

Charles Murray, from one of his conversations with Bill Kristol:

“I, along with Dick Herrnstein, my co-author, we put in italics all sorts of times that IQ is just one of many features that go into determining success, etc., etc. But then I was saying to myself, yeah, but what about the person who gets the short end of the stick on a whole bunch of things? So he has not only got an IQ of 90, which is a little below average, he is not really very handsome, he’s not really very charming, he’s not super diligent. And in none of these ways is he a bad person; but he really got the short end of the stick in a whole bunch of dimensions. And so, he’s not going to be famous and rich and get satisfactions from that kind of success. The question that then became really central to me is, okay, how does this guy live a satisfying life, a deeply satisfying life?”

He continues:

“And that’s what pushed me toward the emphasis that I have had in things that I’ve written ever since 1988 on family, vocation, community and faith as being the four domains – Arthur Brooks calls them ‘the institutions of meaning,’ which is a nice phrase – within which people of a very wide range of abilities can get to be my age and they can be proud of themselves and genuinely satisfied with who they’ve been and what they’ve done. But the trick is, and this also characterizes my work since 1988, those four institutions have to be rich and vital. Communities have to be rich and vital, families do, vocation does and faith traditions do, too.”

He is essentially making the same point as Harden.

College-educated people, good-looking people, talented people. They can derive some satisfaction from their work. Or at least it is within the realm of possibility for them to find an interesting and/or fulfilling occupation. Most people don’t have that option.

I mentioned this in my first essay about luxury beliefs: “most Americans do not have the luxury of a “profession.” They have jobs. They clock in, they clock out. Without a family or community to care for, such a job can feel meaningless.”

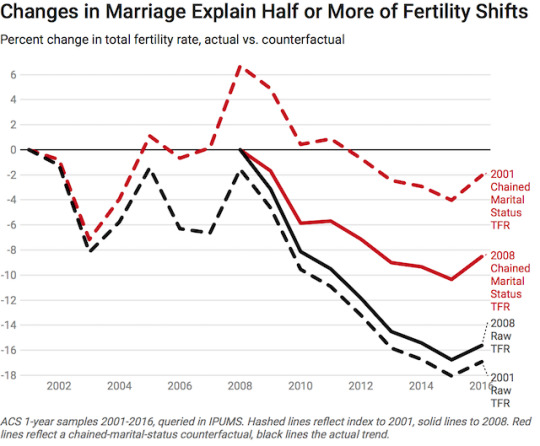

Today, college-educated people are more likely to have interesting jobs. And they are more likely to have stable families. They get both occupational and familial satisfaction. For the less educated, it has become harder to obtain either.

As the sociologist Andrew Cherlin has written:

“A half-century ago, the family structures of poor and nonpoor children were similar: most children lived in two parent families. In the intervening years, the increase in single-parent families has been greater among the poor and near-poor. The divorce rate in recent decades appears to have held steady or risen for women without a college education but fallen for college-educated women. As a result, differences in family structure according to social class are much more pronounced than they were fifty years ago.”

I worked at a pizza joint when I was a teenager. Most of my coworkers were in their twenties, some in their thirties. My manager was in his forties, and had spent some time in prison.

They weren’t bad people. Some were more reliable and honest than anyone else I’d ever meet. But they weren’t going to college. They weren’t going to land an interesting and lucrative job in our small California town. And they had no desire to leave.

It’s hard for many people to accept this. Most people are not exceptionally brilliant, or strikingly attractive, creative, athletic, musical, etc. Most people are perfectly average. One goal of a decent society is to ensure that such people can live with dignity and feel valued in their community, regardless of their endowments. Social guardrails used to help with this. Maybe the absence of guardrails—unrestrained freedom—can work if you're a very smart young person from an upper-middle-class family and there aren't a lot of opportunities around you for your life to go in a catastrophic direction. But if you're a teenager in a place like Red Bluff or in other rundown parts of the country, unconstrained freedom will just give you opportunities for your life to unravel.

1 note

·

View note

Text

You Need the Stamina and Mindset of a Professional Athlete to Make It in Business (more) a reminder that success takes stamina, and you get stamina by training and experience (more)

It wasn’t until my mid-30s that I finally got to see some very successful people up close for long enough to notice a strong pattern: the most successful have a lot more energy and stamina than do others. Which was a disappointment, as I could clearly see that I didn’t have as much stamina as they.

The quotes above are about business management, but it also seems true in many other achievement areas. And while those above quotes focus on what you can do to increase stamina, I’m not sure you can change your stamina that much. You can do a few things, but stamina seems to me pretty resistant to conscious efforts to change it.

Of course stamina isn’t the only thing you need. It also helps to have motive, drive, intelligence, beauty, connections, charm, and many other things. But without stamina, you won’t be able to use those other things as many hours a day, which in close contests can make all the difference.

I think this helps explain many cases of “why didn’t this brilliant young prodigy succeed?” Often they didn’t have the stamina, or the will to apply it. I’ve known many such people. It helps explain why women have often suffered so much career-wise when they had more family demands, or when they were expected to have such soon. And why ambitious women often seem so sensitive on the topic of fertility.

I also think this explains why so many career paths have early periods with that place huge time and energy demands on competitors. With crazy unproductive work hours, as in medicine, law, and academia. These demands often seem counter productive from the point of view of learning, production, or flourishing. But they may do well at distinguishing those with the most energy and stamina, and this may be their point.

If this all is true, why don’t we hear more about it when people talk about success? And why, when people do talk about stamina, do they focus so much on attitudes or practice that might improve something that is in fact hard to change? Why not suggest that people gauge their stamina, or potential for it, early on, and then calibrate their hopes for success accordingly?

The obvious answer: honestly about the stamina-success connection conflicts with our (forager-sourced) egalitarian norms, which promise that anyone can succeed if only they try in the right way. We’d rather give everyone hope than help the hopeful to better calibrate their success potential.

0 notes

Text

I read a useful paper titled “Irrational time allocation in decision-making.”

At the start of the study, participants viewed images of different snack foods and indicated how much they would be willing to pay for each item.

Next, participants looked at images that contained pairs of different foods (e.g. the screen would display a Kit Kat and a Mars Bar). They had to choose which item they preferred to eat at the end of the study.

Researchers found that people spent longer choosing between options that were roughly equal in value than between options in which there was a large value disparity.

“Value” here means how much participants said they would be willing to pay for each item at the start of the study.

When shown a disfavored food alongside a favored food, people chose fast. When shown a favored food alongside another favored food, people took a while. But this is irrational (at least in the economic sense).

When making decisions, we spend too much time choosing between options with roughly equal utility.

This idea is satirized in the philosophical paradox of Buridan's ass, where a donkey that is equally hungry and thirsty is placed exactly halfway between a stack of hay and a bucket of water. Unable to choose between them, it dies.

In another study, participants viewed a series of images containing two fields of dots (e.g., 20 dots on one side of the screen and 10 on the other). For each trial they were shown a different image with two fields of dots. Participants had to decide which side had more dots. They were paid based on how many trials they got right. The more trials they responded to, the more they got paid.

In trials where the number of dots on each side of the screen was nearly equal, participants took significantly longer to choose than when there was a clear disparity. Again, this is irrational.

Participants would have made more money if they had just quickly made a decision and moved to the next trial.

In some of the trials, the researchers imposed artificial time constraints. Participants made decisions faster and thus made more money when researchers told them they had a limited amount of time to respond in each trial.

The researchers conclude, “people apparently misallocate their time, spending too much on those choice problems in which the relative reward is low.”

I thought about cases where this idea would apply. If choosing between the University of Phoenix and UC Berkeley, then you wouldn’t spend much time deciding. If choosing between UC Berkeley and UCLA, many would, even after weighing the pros and cons and determining that they would enjoy the experience at both colleges, spend a painstaking amount of time on this decision.

Another example is what movie to watch. If you’re deciding between movies that all seem appealing and all score above 90 percent on rotten tomatoes, then you’ll probably enjoy any one you choose.

Some people spend way too long at restaurants deciding what to order. Pick a couple of items that sound good and then ask the server which is better.

Or take vacations. If your choices for a holiday are Barcelona or Pyongyang, the choice is (probably) easy. But if you’re deciding between Barcelona or Rome, this should be easy too.

Still, sometimes options are not straightforward. As George MacGill has said, “When presented with two options, choose the one that brings about the greater amount of luck.”

Even if two choices are equal, one might bring you more luck.

If two gyms are equidistant from your house and you’re single and looking to meet someone, perhaps it would be wiser to join the gym that is next to a cafe or a grocery store.

Sometimes the decision-making process itself is pleasurable. Even if all outcomes will be equally rewarding, spending time discussing options with others or privately mulling them over might be satisfying.

There is other research suggesting that people take longer to distinguish between two numbers when there is a small discrepancy than when there is a large one.

For example, people take longer to determine which number is larger between 47 vs. 49 than for 12 vs. 35. Researchers refer to this as “numerical discrimination.”

A recent paper titled “The Adaptive Value of Numerical Competence” describes the idea:

“Similar numerical values are difficult to discriminate, but discrimination performance is systematically enhanced the more different (or distant) two values are (an effect called ‘numerical distance effect’).”

Perhaps this tendency is one reason why people take so long to choose between two options with roughly equal payoffs. Just as we have difficulty distinguishing numbers that are nearly equal in value, we also have difficulty selecting between options that are roughly equal in utility.

I am curious whether this works in the opposite direction—whether duration of decision-making implies equal utility.

When options are roughly equal, people tend to take a long time to make a decision.

Does this also imply that if people take a long time to decide, then the options are roughly equal? Maybe the longer we take to make a decision, the less it matters what we actually choose.

As an aside, people appear to have different emotional responses to the words “choices” and “options.” They mean the same thing. But feel different.

“Making choices” feels scary. “Having options” feels empowering.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are my highlights from the second half of The Daily Laws: 366 Meditations on Power, Seduction, Mastery, Strategy, and Human Nature by Robert Greene—55 lessons that stood out—along with some brief commentary.

[...]

2.“Timidity is a protection we develop. If we never stick our necks out, if we never try, we will never have to suffer the consequences of failure or success…In truth, timid people are often self-absorbed, obsessed with the way people see them, and not at all saintly.”

The kind of person Greene describes here echoes the descriptions of vulnerable narcissism. People with this trait mixed feelings about seeking attention. They are overly excited at the prospect of positive feedback. But excessively sensitive to negative feedback. They have a high opinion of themselves, though this opinion can be thwarted if the external world does not validate it. Although vulnerable narcissists require external feedback to maintain their sense of self, they are often dissatisfied with the feedback they receive.

Vulnerable narcissists hide their aspirations and often appear modest and uninterested in social success. They react with shame or rage when their lofty ambitions are revealed and feel anxious when their exhibitionistic desires are exposed.

So they seek to remain cocooned in order to protect their delicate self-image from ridicule.

[...]

4. “Most people do not want to expend the effort that goes into thinking about others…They are lazy. They want to be themselves, speak honestly, or do nothing, and justify this to themselves as stemming from some great moral choice.”

[...]

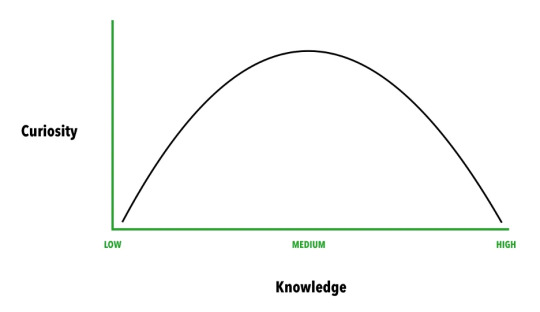

So is self-knowledge and conscious (as opposed to unconscious) strategy beneficial? I think of it as J-shaped curve.

Being oblivious makes you relatively capable of attaining your desires (most humans and all other organisms exist at this part of the J curve; not a bad place to be). Then, once you start to gain awareness of your inner drives and ambitions and how others perceive you, you become more self-conscious and less effective. But as you continue to learn and grow and reach a point of internalizing your newfound knowledge, you level up and reach your highest point of effectiveness.

Fighting works this way, too. When you act on instinct, you can be a fairly capable, if sloppy, combatant. When you have trained for a few weeks and try to implement your new skills, you second-guess yourself (“Am I throwing this punch properly?”) and get wrecked. But when you attain some level of mastery, you revert back to instinct, sharpened and refined through thousands of hours of training.

A quote from Bruce Lee:

“Before I learned martial arts, a punch was just a punch, a kick was just a kick. When I studied martial arts, a punch was no longer just a punch, a kick was no longer just a kick. Now that I understand martial arts, a punch is just a punch, a kick is just a kick.”

You can apply this to many other human endeavors.

5. “Play with ambiguity…show attributes that go against your physical appearance, creating depth and mystery. If you have a sweet face and an innocent air, let out hints of something dark, even vaguely cruel in your character. It is not advertised in your words, but in your manner. Do not worry if this underquality is a negative one…people will be drawn to the enigma anyway, and pure goodness is rarely seductive. No one is naturally mysterious, at least not for long; mystery is something you have to work at.”

6. “Normally we try to charm people with our own ideas, showing ourselves in the best light…In a world where people are increasingly self-absorbed, this only has the effect of making others turn more inward…The royal road to influence and power is to go the opposite direction: Put the focus on others. Let them do the talking. Let them be the stars of the show…Such attention is so rare in this world and people are so hungry for it.”

[...]

8. “The power of verbal argument is extremely limited, and often accomplishes the opposite of what is intended. As Gracián remarks, ‘The truth is generally seen, rarely heard’…demonstrate your ideas through action.”

When I was a kid, my 50 year old boxing coach showed me an old photo of himself when he was much younger. “Normally,” he said, “I say never take fitness advice from people who aren’t in better shape than you.” He patted his round stomach. “But I’ll caveat it and say it’s okay to take workout advice from people who used to be in better shape than you.”

[...]

13. “A heckler once interrupted Nikita Khrushchev in the middle of a speech in which he was denouncing the crimes of Stalin. ‘You were a colleague of Stalin’s,’ the heckler yelled, ‘why didn’t you stop him then?’ Khrushchev apparently could not see the heckler and barked out, ‘Who said that?’ No hand went up….After a few seconds of tense silence, Khrushchev finally said in a quiet voice, ‘Now you know why I didn’t stop him.’ Instead of arguing…he made them feel the paranoia, the fear of speaking up, the terror of confronting the leader…no more argument was necessary…Your goal must be to make them literally and physically feel your meaning, rather than pouring words over them.”

Show, don’t tell.

[...]

18. “Too often there is a chasm between our ideas and knowledge on the one hand and our actual experience on the other. We absorb trivia and information that take up mental space but get us nowhere…We also have many rich experiences that we do not analyze enough…Strategy requires a constant contact between the two realms…Events in life mean nothing if you do not reflect on them in a deep way, and ideas from books are pointless if they have no application to life as you live it.”

This echoes how grand strategy is defined by the historian (and my former professor) John Lewis Gaddis in his book On Grand Strategy:

“The alignment of potentially unlimited aspirations with necessarily limited capabilities…Whatever balance you strike, there’ll be a link between what’s real and what’s imagined.”

Linking the abstract and the concrete. Your life experiences are fleeting, information you read tends to fade, your vision for your future is lofty but unclear. Grand strategy involves drawing useful and actionable information from the trials of our lives and the information we consume to construct a firm bridge between our existing reality and our imagined future.

19. “Far more harm is caused in this world by stupidity and incompetence than outright evil. Those who are overtly evil can be combated, because they are easy to recognize and fight against. The incompetent and stupid are far more dangerous because we are never quite sure where they are leading us, until it is too late.”

[...]

23. “The essence of strategy is not to carry out a brilliant plan that proceeds in steps; it is to put yourself in situations where you have more options than the enemy does. Instead of grasping at Option A as the single right answer, true strategy is positioning yourself to do A, B, or C depending on the circumstances…strategic depth of thinking, as opposed to formulaic thinking…Rid yourself of the illusion that strategy is a series of steps to be followed toward a goal.”

[...]

26. “The problem faced by those of us who live in societies of abundance is that we lose a sense of limit. Abundance makes us rich in dreams…But it makes us poor in reality. It makes us soft and decadent, bored with what we have and in need of constant shocks to remind us that we are alive.”

When life gets too comfortable, many people inflict unpleasant experiences on themselves. So many white collar guys I know are running 10-20 miles a day or training for a tough mudder or getting into micro-dosing or psychedelics. Back when I was washing dishes for minimum wage the idea of an “ice bath” would have been hilarious. But now…I’d give it a try.

On Loveline, Dr. Drew and Adam Carolla would occasionally speak to dominatrixes, and these women said that most of their clients were rich guys; executives, politicians, attorneys. Carolla said this is because blue collar guys who do physical labor all day don’t want to pay someone to humiliate and abuse them, but for those who spend their days making high-stakes decisions in an office, it feels good to let someone else take control. Relatedly, the psychologist Roy Baumeister has suggested that masochism is a form of “escape from the self,” or a way of reducing the burden of self-awareness by relinquishing autonomy. He cites research indicating that among men who visit escorts, there are far more masochists than sadists. And at BDSM parties, it is far more likely that people grumble that there aren’t enough sadists than that there aren’t enough masochists.

27. “Stop thinking of time as an abstraction: in reality, beginning the minute you are born, time is all you have. It is your only true commodity.”

At a certain age and income level, it is wiser to spend money to save time rather than spending time to save money.

Back when I was 22, my instructor at Airman Leadership School (mandatory training to become a non-commissioned officer) was a Filipino American guy who had served time in prison. He later reformed himself, got really into mindset/self-help stuff, and managed to get a waiver to enlist. One day after class, he told me to get a cleaner for my apartment. I asked whether it was a good use of money. He replied by asking “How much is your time worth?” I hired a cleaner.

28. “In ancient Rome, a group of men loyal to the Republic feared that Julius Caesar was going to make his dictatorship permanent and establish a monarchy. In 44 B.C. they decided to assassinate him, thereby restoring the Republic. In the ensuing chaos and power vacuum Caesar’s great nephew Octavius quickly rose to the top, assumed power, and permanently ended the Republic by establishing a de facto monarchy. After Caesar’s death it came out that he had never intended to create a monarchical system. The conspirators brought about precisely what they had tried to stop. Invariably, in these cases, people’s thinking is remarkably lazy: kill Caesar and the Republic returns, action A leads to result B. Understand: Any phenomenon in the world is by nature complex. The people you deal with are equally complex. Any action sets off a limitless chain of reactions. It is never so simple as A leads to B. B will lead to C, to D, and beyond. Other actors will be pulled into the drama and it is hard to predict their motivations and responses.”

Cassius, Brutus, and the other conspirators who assassinated Caesar were tacticians, not strategists. Consider the downstream consequences of your actions rather than the immediate possible gains.

[...]

30. “Wise generals through the ages have learned to begin by examining the means they have at hand and then to develop their strategy...Dreaming first of what you want and then trying to find the means to reach it is a recipe for exhaustion, waste, and defeat.”

Understanding how your concrete means can achieve your unrealized ambitions is the essence of grand strategy.

31. “The problem that many of us face is that we have great dreams and ambitions...The piecemeal strategy is the perfect antidote to our natural impatience...taking small steps makes them seem realizable. There is nothing more therapeutic than action.”

If you don’t want to work out, just do the warmup. If you don’t want to warm up, just put on your gym shoes.

If you don’t want to write, just edit. If you don’t want to edit, just review your work. If you don’t want to review your work, just open the document.

It’s sad, but these little mental tricks work.

32. “So much of power is not what you do but what you do not do—the rash and foolish actions that you refrain from before they get you into trouble.”

I have written that much of the benefit of the military for me wasn’t that it led me to do smart things; rather, it prevented me from doing dumb things. The environment is so rigid, especially during a recruit’s first couple of years, that it dramatically increases the amount of friction to do something catastrophically stupid.

[...]

35. “We humans have a dirty little secret…the secret is that all of us, to some degree, are in pain. It’s a pain that we don’t discuss or even understand. The source of this pain is other people…our often disappointing, superficial, unsatisfactory relationships…leading to a lot of loneliness. It comes in the form of bad choices for associates and partners—leading to…struggle and messy breakups. It comes from letting some toxic narcissist into our life…it also comes from our inability to persuade, to move people, to influence them, to get them interested in our ideas—generating feelings of frustration and anger…We only see the surface phenomenon—the loneliness or the depression or physical ailment. We don’t see the underlying source. And sometimes we’re not even aware that we suffer from loneliness.”

Sociometric status (respect and admiration from peers) is a far stronger predictor of happiness than socioeconomic status. In fact, being liked and held in high esteem is often the main reason people pursue money and worldly success in the first place.

[...]

37. “You might be tempted to imagine that this knowledge of human nature is a bit old-fashioned. After all…we are now so sophisticated and technologically advanced, so progressive and enlightened; we have moved well beyond our primitive roots; we are in the process of rewriting our nature. But the truth is in fact the opposite—we have never been more in thrall of human nature and its destructive potential than now…Look at aggression that is now openly displayed in the virtual world, where it is so much easier to play out our shadow sides without repercussions. Notice how our propensities to compare ourselves with others, to feel envy, and to seek status through attention have only become intensified with our ability to communicate so quickly with so many people…The potential for mayhem stemming from the primitive side of our nature has only increased…Refusing to come to terms with human nature simply means that you are dooming yourself to patterns beyond your control and to feelings of confusion and helplessness.”

[...]

39. “Come to terms with the fact that 95% of your ideas and opinions are not your own—they come from what other people have taught you, from what you're reading on the internet, from what other people are saying...You're a conformist. That's who you are…only by throwing some light on yourself…can you begin to question and overcome…Don’t assume that…you feel something, and it’s right just because you feel it…Ask yourself, ‘Where did I pick up this belief?””

[...]

41. “The incurably unhappy and unstable have a particularly strong infecting power because their characters and emotions are so intense. They often present themselves as victims, making it difficult, at first, to see their miseries as self-inflicted.”

42. “We humans tend to be incredibly conventional…We’re afraid to think for ourselves. The classic example of this cowardice in thinking comes from academics—the people who are supposed to be the most brilliant thinkers of all—many of whom have been largely indoctrinated in a particular way of looking at the world, filled with jargon and orthodoxies…everything they write, everything they see, everything they think about is in that little bubble that they have been inculcated with.”

43. “Of all human emotions, none is uglier or more elusive than envy, the sensation that others have more of what we want—possessions, attention, respect…And so as soon as we feel the initial pangs of envy, we are motivated to disguise it to ourselves—it is not envy we feel but unfairness at the distribution of goods or attention, resentment at this unfairness, even anger…Sitting with one’s envy over a long period of time can be painful and frustrating. Feeling righteous indignation against the envied person, however, can be invigorating. Acting on that envy, doing something to harm the other person, brings satisfaction, although the satisfaction is short lived because enviers always find something new to envy.”

Envy is indeed a dispositional trait. Some people are more prone to it than others.

Young adults experience envy more frequently than older adults. This link remains even when controlling for education and income.

Bertrand Russell on envy:

“You may envy Napoleon. But Napoleon envied Caesar, Caesar envied Alexander, and Alexander envied Hercules, who never existed. You can get away from envy by avoiding comparisons with those you imagine, perhaps falsely, to be more fortunate than yourself.”

Elsewhere, Greene has written:

“You normally focus on those who seem to have more than you, but it would be wiser to look at those who have less...gratitude is the best antidote to envy...Gratitude is a muscle that requires exercise or it will atrophy.”

44. “The root of the Latin word for envy, Invidia, means ‘to look through, to probe with the eyes like a dagger.’ The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer devised a quick way to test for envy. Tell suspected enviers some good news about yourself—a promotion, a new and exciting love interest, a book contract. You will notice a very quick expression of disappointment. Their tone of voice as they congratulate you will betray some tension and strain. Equally, tell them some misfortune of yours and notice the uncontrollable microexpression of joy in your pain, what is commonly known as schadenfreude. Their eyes light up for a fleeting second. People who are envious cannot help feeling some glee when they hear of the bad luck of those they envy.”

Avoiding envy and its attendant dangers is a key reason why people will often conceal or downplay good news about themselves.

[...]

51. “Whenever anything goes wrong, it is human nature to blame this person or that. Let other people engage in such stupidity...you yourself are largely the agent of anything bad that happens to you...when something goes wrong, look deep into yourself.”

Even if something bad happens to you and it is not your fault, it is still your responsibility. Perhaps you can’t be blamed for your misfortunes. But you can be held responsible if you do nothing to improve your circumstances, particularly when the catastrophes that befell you begin to affect others. When I was a foster kid facing my impending high school graduation and realizing I had no prospects in my increasingly desperate life, I didn’t ask, “Who is at fault for this, who can I blame?” Instead, I asked, “what can I do to improve my circumstances as quickly as possible?”

52. “Instead of merely congratulating other people on their good fortune, something easy to do and easily forgotten…actively try to feel their joy, as a form of empathy…Internalize other people’s joy. In doing so, we increase our own capacity to feel this emotion in relation to our own experiences.”

[...]

54. “The greatest danger you face is your general assumption that you really understand people and that you can quickly judge and categorize them. Instead, you must begin with the assumption that you are ignorant and that you have natural biases that will make you judge people incorrectly. The people around you present a mask that suits their purposes. You mistake the mask for reality.”

As I mentioned in Part 1, I am skeptical that such statements apply to everyone. Most people are open books—what you see is what you get. It takes too much effort to constantly be something you’re not, and most people don’t have the ability to deceive others for a lengthy period of time. But a small percentage of people are indeed gifted at wearing masks.

55.“In cultures around the world, they created rituals...awareness of magnificent forces that transcend the human...In our culture we do not easily find such guides...the media that dominates our minds gluts us on trivia and exaggerated dramas of the moment.”

A question I ask myself if I am tempted by clickbait or a trending article or video:

Will this matter or make a difference in my life a year from now? If the answer is no, I’ll usually pass.

0 notes

Text

I’ve been combing through my notes on Robert Greene’s 2021 compilation The Daily Laws: 366 Meditations on Power, Seduction, Mastery, Strategy, and Human Nature.

Greene is best known for his masterpiece The 48 Laws of Power. He has also written books about strategy, seduction, mastery, and human nature.

The Daily Laws encompasses 366 concise lessons (one for each day of the year—leap year included) drawn from Greene’s previous books, interviews, and essays.

Here are my favorite excerpts from the first half of the book—50 lessons that stood out—along with my reactions and commentary on some of the excerpts.

1. “Consider The Daily Laws as a kind of bildungsroman…from the German meaning ‘development’ or ‘education novel’…In these stories, the protagonists, often quite young, enter life full of naïve notions. The author takes them on a journey through a land teeming with miscreants, rogues, and fools. Slowly, the protagonists learn to shed themselves of their various illusions as the real world educates them. And they come to see reality is infinitely more interesting and richer than all the fantasies they had been fed on. They emerge enlightened, battle-tested, and wise beyond their years.”

2.“What often happens is that at a fairly young age, burdened with such delusions, we enter the work world, and reality suddenly slaps us in the face. We discover that some people have fragile egos and can be devious and not at all what they seem. We are blindsided by their indifference or sudden acts of betrayal. Being ourselves and just saying what we think can land us in all kinds of trouble. We come to realize that the work world is riddled with political games that nobody has prepared us for.”

3. “Our culture tends to fill our heads with all kinds of false notions, making us believe things about what the world and human nature should be like, rather than what they are actually like.”

Greene takes a cynical view of all of human nature, which I have some disagreement with. He and his predecessors (e.g., Machiavelli, La Rochefoucauld) help their readers understand a narrow slice of humanity. Particularly those who are ambitious, competent, self-aggrandizing, and hungry for status and/or power. These types tend to score highly on the Dark Triad personality traits (psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism). These individuals exist everywhere. But the higher up you go, the less detectable and more capable they tend to be.

For example, despite accounting for just two percent of the general population, psychopaths make up 8 percent of college students, 13 percent of business executives, and 20 percent of prison inmates. Most people would enter prison and anticipate that many of their fellow inmates will be callous, cynical, and cruel. But in academic or business environments, such types are also surprisingly prevalent. And they are frequently gifted at concealing it.

These people intrigue us, threaten us, and occupy so much of our mental real estate that Greene and others mistakenly overextend the qualities they have to everyone else.

Put differently, most people are generally kind, cooperative, and docile. And seldom cold and calculating. But a sizable handful are not. If you regularly interact with socially adept and ambitious people, then reading Greene’s work can illuminate the kinds of characters you will sometimes encounter and provide valuable tips.

4. “The most pleasurable things in life occur as a result of something not directly intended and expected. When we try to manufacture happy moments, they tend to disappoint us. The same goes for the dogged pursuit of money and status.”

This echoes one of the most influential passages I have ever read, from Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl:

“Success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect...success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think of it.”

[...]

8. “In fact, it is a curse to have everything go right on your first attempt. You will fail to question the element of luck, making you think that you have the golden touch. When you do inevitably fail, it will confuse and demoralize you.”

[...]

10. “In the Apprenticeship Phase...If you are not careful, you will accept this status and become defined by it, particularly if you come from a disadvantaged background...you must work to expand your horizons...be relentless in your pursuit for expansion.”

Sometimes, as you grow in experience and knowledge, others will continue to view you as a novice. Moving into a new environment or surrounding yourself with different people can help you shed that old image. I saw this on occasion in the military. A new recruit would make rank and become a non-commissioned officer. But others didn’t treat him any differently, they still saw him as a rookie. When he’d relocate to a new duty station, though, people would see the stripes on his sleeve and give him his due. Because they only ever knew him as that particular rank.

[...]

17. “Mistakes and failures are precisely your means of education. They tell you about your own inadequacies. It is hard to find out such things from people, as they are often political with their praise and criticisms. Your failures permit you to see the flaws.”

[...]

22. “In your desire to please and impress, do not go too far in displaying your talents or you might…inspire fear and insecurity. When you show yourself in the world and display your talents, you naturally stir up all kinds of resentment, envy, and other manifestations of insecurity…outshining the master is perhaps the worst mistake of all. Make your masters appear more brilliant than they are, and you will attain the heights of power. If your ideas are more creative than your master’s, ascribe them to him, in as public a manner as possible. Make it clear that your advice is merely an echo of his advice. If you surpass your master in wit, it is okay to play the role of the court jester, but do not make him appear cold and surly in comparison… Always make those above you feel comfortably superior.”

[...]

26. “In the social realm, appearances are the barometer of almost all our judgments, and you must never be misled into believing otherwise…Reputation has a power like magic…Whether the exact same deeds appear brilliant or dreadful can depend entirely on the reputation of the doer.”

27. “A fortress seems the safest. But isolation exposes you to more dangers than it protects you from—it cuts you off from valuable information…Since power is a human creation, it is inevitably increased by contact with other people…To make yourself powerful, place yourself at the center of things, make yourself more accessible, seek out old allies and make new ones, force yourself into more and different circles.”

28. “The way you carry yourself will often determine how you are treated: in the long run, appearing vulgar or common will make people disrespect you...Ask for less and that is just what you will get.”

29. “Have no mercy. Crush your enemies as totally as they would crush you. Ultimately the only peace and security you can hope for from your enemies is their disappearance. It is not, of course, a question of murder, it is a question of banishment...exiled from your court forever, your enemies are rendered harmless.”

30. “Those misfortunates among us who have been brought down by circumstances beyond their control deserve all the help and sympathy we can give them. But there are others who are not born to misfortune or unhappiness, but who draw it upon themselves by their destructive actions and unsettling effect on others. It would be a great thing if we could raise them up, change their patterns, but more often than not it is their patterns that end up getting inside and changing us…Infectors can be recognized by the misfortune they draw on themselves, their turbulent past, their long line of broken relationships, their unstable careers, and the very force of their character, which sweeps you up and makes you lose your reason. Be forewarned by these signs of an infector; learn to see the discontent in their eye. Most important of all, do not take pity. Do not enmesh yourself in trying to help. The infector will remain unchanged, but you will be unhinged…Associate with the happy and fortunate instead.”

Between growing up and seeing the same people repeat the same mistakes over and over along with listening to hundreds of people call into Loveline as a kid, I internalized this lesson by my early twenties. Most people don’t want to change their lives, no matter how unpleasant and disorderly it might be.

[...]

32. “Sir Walter Raleigh was one of the most brilliant men at the court of Queen Elizabeth of England. He had skills as a scientist, wrote poetry still recognized as among the most beautiful writing of the time, was a proven leader of men, an enterprising entrepreneur, a great sea captain, and on top of all this was a handsome, dashing courtier who charmed his way into becoming one of the Queen’s favorites…Eventually he suffered a terrific fall from grace, leading even to prison and finally the executioner’s axe. Raleigh could not understand the stubborn opposition he faced from the other courtiers. He did not see that he had not only made no attempt to disguise the degree of his skills and qualities, but he had imposed them on one and all, making a show of his versatility, thinking it impressed people and won him friends. In fact it made him silent enemies, people who felt inferior to him and did all they could to ruin him the moment he tripped up or made the slightest mistake. In the end, the reason he was executed was treason, but envy will use any cover it finds to mask it destructiveness…Appearing better than others is always dangerous, but most dangerous of all is to appear to have no faults or weaknesses. Envy creates silent enemies.”

A related concept is the “pratfall effect” in social psychology:

Highly competent individuals are viewed as more likable after committing mistakes, while average individuals are viewed as less likable if they commit the same mistake.

[...]

38. “Pay less attention to the words people say and greater attention to their actions. People will say all kinds of things about their motives and intentions...Their actions, however, say much more about what is going on underneath the surface…take special note of how people respond to stressful situations—often the mask they wear in public falls off in the heat of the moment.”

[...]

43. “Weak character will neutralize all of the other possible good qualities a person might possess.”

Studies indicate that when people form impressions of others, they assign the highest importance to moral character. Morality eclipses warmth (e.g., sociability, enthusiasm, agreeableness) and ability (e.g., intelligence, athleticism, creativeness) in personal evaluations.

In fact, when forming impressions of others, people assign more than twice as much importance to moral character than competence.

44. “The feeling that someone else is more intelligent than we are is almost intolerable. We usually try to justify it in different ways: ‘He only has book knowledge, whereas I have real knowledge.’ ‘Her parents paid for her to get a good education. If my parents had had as much money, if I had been as privileged…’ ‘He’s not as smart as he thinks.’ Last but not least: ‘She may know her narrow little field better than I do, but beyond that, she’s really not smart at all. Even Einstein was a boob outside physics.’ Given how important the idea of intelligence is to most people’s vanity, it is critical never inadvertently to insult or impugn a person’s brain power.”

[...]

48. “If you need a favor from people, do not remind them of what you have done for them in the past, trying to stimulate feelings of gratitude…Instead, remind them of the good things they have done for you in the past. This will help confirm their self-opinion: ‘Yes, I am generous.’”

49. “Train yourself to focus on others...People do not want truth and honesty, no matter how much we hear such nonsense endlessly repeated. They want their imaginations to be stimulated and to be taken beyond their banal circumstances.”

50. “Familiarity is the death of seduction…Without anxiety and a touch of fear, the erotic tension is dissolved. Remember: reality is not seductive. Maintain some mystery or be taken for granted…Keep some dark corners in your character.”

People you aim to impress don’t need to know everything about you. Less history, more mystery.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Back in March of this year, I shared a collection of 31 of my favorite quotes from François de La Rochefoucauld along with some of my commentary.

My intro to that post:

La Rochefoucauld was a seventeenth century essayist, memoirist, and perhaps the greatest maxim writer of France. He had a distinguished military and political career. By all accounts, he was an honorable man. One reason for this is that he was aware of humanity’s talent for self-deception, and worked hard to overcome it in himself. In his 1878 book Human, All Too Human, Friedrich Nietzsche compared François de La Rochefoucauld to a “good marksman” who repeatedly hit “the bull’s-eye of human nature.”

Here are 31 more of my highlights from La Rochefoucauld’s Collected Maxims and Other Reflections, along with some brief commentary.

1. “Uncouthness is sometimes enough to save you from being deceived by a clever man.”

A lack of education, refinement, or sophistication can serve as a form of protection against intellectually manipulative people. Uncouth people often aren’t drawn in by intricate arguments or sophistry or complex schemes. They operate on a simpler, more instinctual level and are therefore more protected against overtures designed to flatter and deceive them. As an example, I went my whole life thinking racism meant disliking someone simply because of their ethnic background. Then I got to college and people tried to tell me racism means “power plus prejudice.” I either wasn’t smart enough or wasn’t dumb enough to accept the intellectual acrobatics required to believe that nonsense.

2. “The qualities we have never make us as absurd as those we pretend to have.”

3. “We would rather speak ill of ourselves than say nothing about ourselves at all.”

Performative confessions on social media come to mind.

4. “It is easier to be wise for other people than for yourself.”

In psychology, this is called “Solomon’s paradox.” The reason seems to be that we have more distance from other people’s problems than our own, which allows us to be more impartial. A recent meta-analysis found that over the world, people reason more wisely about other people’s social problems than they do about their own.

5. “No one deserves to be praised for kindness if he does not have the strength to be bad; every other form of kindness is most often merely laziness or lack of willpower.”

So often, people try to advertise their cowardice or weakness as kindness. I have met people who publicly say the current ideological fad is “just being kind” but privately confess to me that they fear losing their jobs.

6. “One of the reasons why so few people seem reasonable and attractive in conversation is that almost everyone thinks more about what he himself wants to say than about answering exactly what is said to him. The cleverest and most polite people are content merely to look attentive––while all the time we see in their eyes and minds a distraction from what is being said to them, and an impatience to get back to what they themselves want to say. Instead, they should reflect that striving so hard to please themselves is a poor way to please or convince other people, and that the ability to listen well and answer well is one of the greatest merits we can have in conversation.”

The ability to listen to someone, respond in a way that indicates you have listened, and not relate their comments to something about yourself, is a rare quality.

7. “Praise is a clever, hidden, subtle form of flattery, which gratifies the giver and the recipient in different ways. The latter accepts it as a reward for his merit; the former bestows it to draw attention to his fair-mindedness and perceptiveness.”

8. “Few people are wise enough to prefer useful criticism to treacherous praise.”

9. “A refusal of praise is a desire to be praised twice over.”

If someone delivers a compliment, the best thing you can do is say you appreciate it or quickly thank them and move on.

10. “Nature creates merit, and fortune puts it on display.”

11. “There are people whose sole merit consists of saying and doing stupid but useful things, and who would spoil everything if they changed their conduct.”

12. “The glory of great men should always be measured against the means they used to acquire it.”

13. “We are sometimes as different from ourselves as we are from other people.”

There is now a large body of evidence in psychology supporting this. Not all of it has convincingly replicated, but there is enough of it to suggest we are indeed different people at different times. When the same software developers were asked on two separate days to estimate the completion time for the same task, their answers, on average, differed by 71 percent. A study of nearly 700,000 primary care visits found that physicians are significantly more likely to prescribe opioids and antibiotics at the end of the work day. It seems that when doctors are tired and under time pressure, they are more inclined to choose a quick-fix solution.

In Noise, Daniel Kahneman and his co-authors are blunt in their conclusion: “We do not always produce identical judgments when faced with the same facts on two occasions … you are not the same person at all times.” That is, as your mood and external circumstances vary, some features of your cognitive machinery vary too.

When wine experts at a prominent wine competition tasted the same wines twice, they scored only 18 percent of the wines identically—usually, the very worst ones. This suggests that while experts tend to agree with themselves on which wines are bad, they often disagree with themselves on which ones are good.

Relatedly, there seems to be a similar pattern for books and academic articles. When a text is clearly bad, reviewers generally agree with one another, but when a text is good, there is often widespread disagreement about its merits.

14. “However brilliant a deed may be, it should never be taken for a great one unless it results from great plans.”

15. “The ability to make good use of average talents is an art that extorts respect, and often wins more repute than real merit does.”

16. “There are innumerable forms of conduct that seem absurd, though their hidden reasons are very wise and very well founded.”

Reminds me of a quote from Donald Kingsbury: “Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems.”

17. “It is easier to seem worthy of positions you do not hold than of those you do.”

18. “There are different forms of curiosity. One is due to self-interest, which gives us a desire to learn what could be useful for us; another is due to pride, and comes from a desire to know what other people do not know.”

19. “Our minds are better employed bearing the misfortunes that do happen to us than anticipating those that could happen.”

20. “What makes us like new acquaintances is not so much our weariness of the old ones, or the pleasure of changing, as frustration that we are not admired enough by those who know us too well, and the hope of being admired more by those who are less well acquainted with us.”

21. “We must admit––and let us honour virtue for it––that men’s greatest misfortunes are those that befall them because of their crimes.”

It’s unfashionable to say in polite society nowadays, but so much misery—perhaps even most—is self-inflicted.

22. “We acknowledge our faults so that our sincerity may repair the damage they do us in other people’s eyes.”

23. “During the course of our lives, the vices await us like landlords at whose inns we must successively lodge; and I doubt whether experience would lead us to avoid them, if we were allowed to travel the same way a second time.”

La Rochefoucauld casts doubt on the notion that, armed with the wisdom of hindsight, we would necessarily make better choices if we were to undergo the same experiences once again. This is overstated in my view—generally, older people really are wiser than younger people. But I do think many individuals miscalculate how much their character improves with experience and maturity.

24. “When vices leave us, we flatter ourselves that we are the ones who are leaving them.”

25. “The desire to be seen as clever often prevents us from becoming so.”

26. “Someone who thinks he can find enough in himself to do without everyone else is greatly deceived; but someone who thinks that other people cannot do without him is still more deceived.”

27. “Love of glory, fear of shame, a plan to make our fortune, a desire to make our lives comfortable and attractive, and a wish to demean other people, are often the causes of the valour that men praise so highly.”

You might be repelled if you learned the hidden motives driving many of the people you so greatly admire.

28. “Hypocrisy is a form of homage that vice pays to virtue.”

Even in the act of being hypocritical, we indirectly acknowledge the importance and value of virtuous behavior. Hypocrisy involves espousing certain principles while acting in a manner contrary to those principles. Usually we view this as a moral failing.

But when you engage in hypocrisy, you typically present a façade of virtue. The choice to exhibit this façade, rather than openly embrace vice or depravity, signals an acknowledgement that virtue is the more praiseworthy and commendable path.

Thus, even though the hypocritical behavior is dishonest, it inadvertently affirms the value system it seeks to sidestep.

In HBO miniseries The Pacific, based on a true account of 3 Marines in the Pacific theater during WWII, there is a scene in which one Marine (nicknamed “Snafu”) stops his friend (Sledge) from digging the gold teeth out of a dead Japanese soldier’s mouth. Interestingly, though, Sledge actually learned this trick from Snafu, who is more blasé about the brutality of war. So when Snafu stops him, he is a hypocrite. But the implication is that Snafu doesn’t want his friend to become like himself—he sees Sledge as a better man and doesn’t want him to reduce himself to such a repugnant act.

In another example, a friend of mine who was sentenced to San Quentin State Prison when he was 21 later explained to me that many older prisoners (most of whom are tattooed) try to talk new inmates out of getting prison tattoos, and that prison tattooists often refuse to be the first one to tattoo a new inmate because they think a prison tattoo will ruin the young inmate’s future.

29. “We are easily consoled for our friends’ misfortunes when such things give us a chance to display our affection for them.”

30. “It is less dangerous to do evil to most men than to do them too much good.”

31. “Nothing flatters our pride more than the fact that great people confide in us, because we regard that as a result of our own merit, without considering that it most often arises only from vanity or inability to keep a secret.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

In his 1878 book Human, All Too Human, Friedrich Nietzsche compared François de La Rochefoucauld to a “good marksman” who repeatedly hit “the bull’s-eye of human nature.”

La Rochefoucauld was a seventeenth century essayist, memoirist, and perhaps the greatest maxim writer of France. He had a distinguished military and political career. [...]

You can read my previous collections of his penetrating maxims here and here.

Below are 18 more of my favorite quotes from La Rochefoucauld:

1. “We confess our small faults only to convince people that we have no greater ones.”

2. “Humility is often merely a pretence of submissiveness, which we use to make other people submit to us. It is an artifice by which pride debases itself in order to exalt itself; and though it can transform itself in thousands of ways, pride is never better disguised and more deceptive than when it is hidden behind the mask of humility.” [...]

3. “The approval we give to those who are just entering society often arises from secret envy of those who are already established there.”

Obviously there are noble motives involved in supporting promising young people. La Rochefoucauld suggests that a hidden and less flattering motive is the thrill people get from supplanting people who are currently in positions of power; seeing them get knocked down a peg.

4. “Moderation has been turned into a virtue to limit the ambition of great men, and to comfort average people for their lack of fortune and lack of merit.”

Both Machiavelli and Nietzsche would agree with this.

5. “To be a great man, you must know how to take advantage of every turn of fortune.”

6. “Most women mourn the death of their lovers less because they loved them than to seem worthy of being loved.”

La Rochefoucauld wrote this in the seventeenth century. An era when lots of women would see their sons and husbands go off to war and die. Interestingly, an evolutionary theory of grief backs up his maxim (not just for women, but for humans in general). The theory posits that the reason humans experience grief in response to the loss of a loved one is in order to signal to social allies and romantic partners that we are loyal. If your best friend or your spouse died and you just shrugged and moved on, other people in your social circle would view you with suspicion. But if you exhibit grief, people then infer that you are a committed and invested social partner who they can trust. Intense mourning is an honest, hard-to-fake social signal that you care about those around you and would therefore be a good ally or romantic partner. High grievers are rated as nicer, more loyal, and more trustworthy than low grievers.

Of course, it’s important to be careful not to confuse the evolutionary motivation with the psychological motivation. From the standpoint of evolution, we eat to sustain our bodies and have sex to pass on our genes. But these are not the personal psychological reason we do these things. They just come naturally to us because evolution instilled in our ancestors feelings and behaviors that, on average, allowed them to survive and reproduce.

7. “However we may mistrust the sincerity of those who talk to us, we always think they are more truthful with us than with other people.”

If someone you know regularly badmouths other people when speaking privately with you, it is a 100% certainty that he or she is badmouthing you when speaking privately to others.

8. “We would often be ashamed of our finest deeds, if people could see all the motives that produced them.”

9. “Nearly all of our faults are more forgivable than the means we use to hide them.”

10. “We should not judge a man’s merit by his great qualities, but by the use he makes of them.”

11. “We would have passionate desires for very few things if we fully understood what we were desiring.” [...]

12. “In friendship, as in love, we are often happier in what we do not know than in what we do know.”

13. “When fortune catches us by surprise and gives us a position of greatness without having led us to it step by step, and without our having hoped for it, it is almost impossible to fill it well and seem worthy of holding it.”

You can see this with people who were selected for important positions or admitted to elite institutions not because of their abilities but because they mouthed the right slogans or ticked the right boxes.