Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Do You Ever Wonder Why We’re Here?

Introduction

It’s four days to my birthday, and just like every year since I’ve started college, I’m going to be spending it alone.

The fact that this is necessitated to keep people safe makes it only marginally easier to bear, but there’s something to this repetition of isolation and loneliness this year that makes it just ever-so-slightly more unbearable. This year, I turn twenty-one, and this year, I was actually going to try and do something for my birthday -- but more than that, I was even trying to make friends.

I was trying to better myself, and for once, it wasn’t even my fault that I failed.

So this social issue blog post goes out to you, SARS-CoV-2.

Thank you for providing me the motivation I need to talk about the effect that generalized anxiety and depression have upon an over-stressed college population.

Part 1: What’s Happening

The rising rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior among college students isn’t, precisely, new information -- over six months ago, after all, Reuters reported that these behaviors have roughly doubled in not even a decade, with over 20% of college students in 2018 reporting themselves with severe depression and over 40% reporting moderate depression. We’ve talked about these numbers in our sociology class; we have looked around the room and seen people realize that in every group of five, one of them is struggling with a usually-unseen demon that is tormenting them unbearably; in every paring, one of them is suffering at some level. Doing a simple search through tools like Google Scholar, and you can find source after source talking about this phenomena: I found six, personally, talking about how LGBTQIA+ students are more likely to face depression and the problems they face, how a sense of self-loathing and continual sadness are some of the most prominent facets of this depression epidemic, how students are more likely to use things like alcohol to try and cope -- and how having other aspects that make you neuroatypical make you even more susceptible to substance abuse -- how the stress that students are faced with, even at a 2-year program, helps lead to depression and sleep problems, and how having access to treatment does help. I found, too, that this isn’t a problem that started being noticed in just this past decade: even back at the turn of the millennia, back in 2001, researchers had noted that the number was still going up.

The causes of this stress and depression tie down tightly to a few core concepts. The rise of social media, of course, is one of those -- but social media is not an aspect of depression unique to college students, though it may be a signifier for the rise of depression among younger groups. What appears to play a far larger role is, instead, the stress that is placed atop the back of college students. Part 2: The Stress

The stress levied to college students is beyond numerous, and it is beyond heavy as well. It’s beyond just coursework, too -- though the coursework definitively does play a massive role in the stress that college students do face during their time at higher learning institutions. The stressors are, in many ways, systemic to how college is handled in the United States, and perhaps might even be seen as a necessary evil -- after all, if high school was to teach you how to learn and process information, perhaps college exists to test those learning skills and the determination and grit that a student possesses. One might say that they are a necessary function, to weed out those that do not “deserve” to have the accolade of learning.

Of course, there are numerous problems with that statement, including the fact that not all of the stressors faced by a college student are strictly academic, and colleges are no longer a strictly academic function for undergraduate students. A student could go through the academic process at a college with relative ease compared to their peers and still struggle with the same problems that they might not have faced had they chosen not to pursue higher learning -- but for many reasons, they felt as though they had to. For many students, this feeling that they have to go to college plays a big role in causing them stress simply because of how unadulteratedly expensive college in the United States is. According to debt.org, the average college student will be $37,172 in debt when they graduate from college, and that number plays no account for how much interest they might accrue as they try to pay that debt off. The fact that college is so prohibitively expensive for so many causes so much of the stress faced by the modern college student, and that stress ties directly into their rates of depression and anxiety.

But there is more than just finances that cause these things. Among other non-academic stressors faced by a college student are those of navigating a complex social web that they have never faced before. If navigating all of the social relationships during high school was difficult for someone, well, the difficulty is on steroids in college. For many, this is their first time living by themselves with full regulation over their schedule and their lives, and at this point, they’re still struggling with the last few years of their mental development. We expect college students to fully be able to live by themselves and know what they want to do with their lives -- and, in many cases, how to get there -- right after what is the most awful periods of their life. The pressure to go to a traditional college, make new friends and lifetime connections -- perhaps, maybe even a partner -- and know what you want to do with your life in what is expected to be a four year time span is experienced by roughly 70% of the graduating high school population.

And it’s hard to blame people for wanting to go to college. That freedom, for many, is beyond liberating, even if it leads to uncertainty. In today’s job market, many jobs require that four year bachelor’s degree to even get your foot in the door -- and, in some fields, that isn’t even good enough; you need now a masters degree in many fields not due to a needed skill but just due to how many people with bachelor’s degrees are applying for that same position. This stress to compete and be able to find a good job, while it does tie in to the academics, puts an extra burden upon college students -- and, when combined with the student loans, pressures and stresses students to perhaps pursue things that they do not enough, which only leads to further problems.

So what do we do?

Part 3: Where Do We Go From Here?

There is no one solution to the conflict that creates stress and depression within college students, because as we’ve seen, this problem is multifaceted. Like a hydra, it wears many faces, and they all work to strike at a vulnerable, confused population. It’s impossible to completely eradicate, too, as part of the rising tides of depression stem from better ability to diagnose it and a changing society -- and though those changes may be for better or for worse, they may be massive or they may be small, those changes are often very hard to impede without massive societal upheaval.

But there are simpler things that can happen to address this problem.

Money is, of course, one of the biggest stressors to a college student -- if not in tuition, then in covering their living expenses. I’m lucky to go to a college where housing is relatively cheap -- this is not a luxury many have -- and still many of the apartments here are just barely affordable and necessitate roommates in a hundred-year-old room in a house that’s been divied up to hold more people than it ever reasonably should have. An increase in minimum wage or a decrease in housing costs would ease this burden, and as Evicted had talked about, there are numerous ways to do the latter. Decreasing tuition -- or increasing federal assistance for more students -- would also allow for similar effects, and we’ve seen a growing advocacy for that recently.

Increased advocacy for students would help too, through methods like expanding the networks designed to get students acclimated to college and assist in forming frendships. I may be a twinge biased, as I worked for them, but I truly do believe that programs like the Orientation program at Michigan Tech, which spends a week trying to help acclimate students to college, does more than just act as “a retention program for the university”. Though, in many cases, the bonds that are formed during it may be temporary, it at least serves to help students get some founding experience for a week before being set loose on the world. Though this program might exist to benefit the university, it, too, benefits the students who experience it.

Some might advocate, too, for people to not go to four year universities and to instead consider a trade, which is undeniably a good alternate to a four year university for some -- but it’s not for everyone. The education, for some, that is received at a “proper” university is what is important -- not the money they receive afterwards, not the job that they get. Education for the sake of learning is a goal that should not be marred by barriers to entry nor serve to lead to a horrible mental state, it is something that should be rewarded and praised. Accessibility to anyone who seeks knowledge should be the goal of a university -- and right now, it puts up an oppressive barricade to those who face mental illness by not properly facilitating an environment that avoids that.

The End.

0 notes

Text

Opiate Movies and You: Understanding the Opioid Epidemic and Recovery Boys.

At this point, the perversion of how doctors were lied to and coaxed into overprescribing opiates to people who, perhaps, might not have needed them is a topic it feels as though we all know about, but from my perspective as a Communications, Culture, and Media student -- specifically, right now, that first and that last part -- it is a conversation that needs to still be repeated and still needs to be talked about, and movies are perhaps one of the best ways to help those around us understand due to the sheer power that they have as a method of mass communication with those around use. Two movies, in particular, assist in furthering our understanding of the opioid crisis in America: Understanding the Opioid Crisis, which, from PBS, has a rather self-explanatory title, alongside Recovery Boys, a movie about the process in which “four men try to reinvent their lives and reenter[sic] society after years of drug abuse”.

Movies are, of course, perhaps one of the best ways to showcase the pains and help us trace the understanding that the directors are trying to give us due to the simple accessibility that they have: anyone can sit down and turn on Netflix to Recovery Boys, and Understanding the Opioid Crisis is just as accessible; for just an hour-and-a-half of your time, the directors of both films were able to successfully paint the rather-bleak picture that suffering through this epidemic inflicts. Though Understanding the Opioid Crisis definitely started to feel a lot more like a documentary -- focusing on an overarching topic and interviewing more people often does that -- it still manages to enthral and impart onto us the pain and suffering that the reckless abaddon pushed onto us by the big pharmaceutical companies through opiates; however, in contrast to Recovery Boys, which is more narrow in focus -- but still manages to convey much of the same ideas -- the documentary almost feels a little bit drab.

But when viewed through the lens of sociology, both outline a meaningful story about how the forces in our western world interact to cause this crisis. By better showing the root causes of the opiate crisis and the pain that it has caused, Understanding the Opioid Crisis highlights the conflict and chaos that resulted from medical corporations trying to make more money by pushing oxycontin and vicodin through overprescribing that was caused by the kickbacks that doctors had received, while Recovery Boys almost seems to analyze the forces that lead those four men into their circumstances and how they all interact. Though both heavily involved in the same topic, the ways that the directors frame the conversation and the depths at which they go are obviously quite different -- but both, in my eyes, are thoroughly successful at analyzing the problems caused by this.

But, to me, that does not mean they’re flawless. Perhaps there was a moment in which I missed it -- going through almost three hours of movies in a short time span does leave some details sparse in my mind -- but, to me, it felt like they didn’t address an inequality that arose when opiates started to become a problem for “white America” as well: that is, they didn’t address how heroin and opiates were originally seen as a poor person, a black person’s drug, and when just them were dying it wasn’t as much of a problem until all of the sudden it started to affect the middle class as well. It’s entirely possible that this was covered, and was a detail that I simply had just missed -- but if that isn’t the case, it’s a disappointing point to have seen not covered.

Thankfully, though, that is my only true problem that I had with the films. I’m a relatively easy audience to entertain, thankfully, so I had no real other complaints, and anything I could think of would likely be nitpicks that might have not been at all able to have been handled due to the documentary nature of these films. For any student -- hell, for any person -- who wants to better understand one of the biggest problems facing America at this time, I truthfully believe that these two films do an amazing job at addressing the issues faced through the opiate crisis.

0 notes

Text

34.3%

That number is the percentage of all students at my university, Michigan Tech, voted in 2016. That number is up from 2012 by almost five percent, but still remains more than fifteen percent below the national average for all college institutions, according to the August 2017 NSLVE report on Michigan Tech’s Student Voting rates.

34.3%

To me, at least, that number is shockingly low -- but once you look further into the report, it becomes almost easier to make some sort of sense as to why the percentage of Tech students who go out and vote is so low. Ignoring, of course, the trend that younger people tend to vote less and most of Tech’s student body is fairly young, what you see is that most of the majors that are chosen up here -- the STEM-focused ones, that is -- fall below not even that national average but the school average too, with the lowest being the maths and the physical sciences. It almost seems, even, that the further you get from the focus on science, the higher the rates become, with Tech’s few education majors and slightly more communication majors being the highest majors on Tech’s campus to vote. However, even among majors where you would hope people would be encouraged to vote, such as the students in Michigan Tech’s social sciences programs, the rates there are just barely above the Tech average at 34.9%. It’s also unclear as to what the seventy-two students who are enrolled in “other” degrees and/or fields are a part of, but they voted at a higher rate as well.

Looking at the gender and the ethnicity rates, as well, there is no massive difference between the groups: the national trend of women voting more than men and white Americans voting more than black Americans still hold true, but the rates are still very low, and only women voted more than the Tech average. The more this data is looked at, the more it suggests that there has to be something more at play that cannot just be shown by looking at this number. There might exist, in some sense of a symbolic interaction, a lack of pressure or focus placed upon voting at Michigan Tech due to the almost-apolitical climate that science tries to present itself with; however, to fully blame it on societal forces might not be the best result -- especially when you look at the time in which these results took place, alongside how the majority of Tech students had placed their votes.

So, how did most Tech students vote?

Through absentee ballots.

In the state of Michigan, voting through absentee ballots was pragmatically -- and almost seemingly deliberately -- obtuse, and when 65% of the student body is voting that way, any barrier to entry through this voting method drastically affects the student body’s ability to vote. Most Tech students are from the lower peninsula of the state of Michigan, which means that, even if they are at the northernmost point where the bridge connects the two parts of the state, they are a five hour drive away from home.

What this points to is an extremely effective disenfranchisement technique in which a voting body that is already less likely to vote -- that is, younger voting blocks vote in lesser numbers than older ones despite being numerically larger -- face such a high barrier to be able to vote due to the obtuse methods previously required to obtain an absentee ballot in the state of Michigan.

Thankfully, in 2018, Michigan voters voted to change how absentee voting was run, and in doing so, it became a lot easier for residents of the state to vote via an absentee ballot. While Michigan Tech’s culture in being more science-and-STEM focused than on the society and culture around us might mean the people up here are less likely to vote, there had been a historical problem with the ease in which people could vote -- and it’s been shown, time and time again, that when voting is made difficult, people vote less.

We won’t truly know how much of a role the difficulty in voting as an absentee had until this election cycle concludes this November, but more than any level of interaction between Tech students, Tech faculty, and the culture that envelops them all, it feels as though this simple barrier onto how Tech students ability to even vote might have been the biggest source of the woeful voting number that we see.

0 notes

Text

“Like most queer people, I find nothing more fascinating than an in-depth analysis of my own personality”

That is perhaps my favorite quote from Natalie Wynn’s latest video on her YouTube channel, ContraPoints. The entire video, of course, is a goldmine of introspective queer humor, due in heavy part to what it focused on talking about: shame, and Natalie’s own shame in her sexuality as a trans individual.

But of all the lines that make me laugh, this one struck me a little bit more than just a quick laugh. While I, myself, have some issues with Natalie -- who doesn’t love the Twitter drama? -- she had made an incredibly interesting point that had left me thinking: why do I love to introspect so much about my personality, and more than just my personality: my whole identity is something I regularly question and explore the avenues that have led me into this path.

And given the chance to do so again, I will always gladly do so.

Of course, so that we’re not here all day, there has to be at least a little bit of fat pared off, but at the same time, there is a role that I fit into that, at my core, defines a lot of who I am: it’s my status as a queer individual. Being queer has shaped so much of my life, from my gender identity, to my sexuality, to my friends, and to what I even want to do for a career. While being queer is something that I just am, there are parts of society that have influenced how I represent my queerness, either because I want to look that way (my love for rainbows, perhap) or because I want to stand as a counterpoint to a specific helm of ideas.

At first, though, there weren’t any really ideas that spring to mind as affecting my sexuality or gender identity long ago; however, part of that might be because I’ve identified as some shade of bisexual for a very long time, since about 5th grade, and so even if there was something that really affected that process, I don’t think I’d be able to recall it. Part of how I would grow to express it, maybe, would be shaped by my gay uncles, but for the longets time, I was the only queer person I knew. I didn’t know anyone else who was gay online or in real life, I didn’t consume any media with queer people in it, and there wasn’t a whole lot of talk about it. A big part of that was because of just how young I am -- society, after all, has a phobia towards talking to kids about being gay or trans or really any shade of queer.

As I grew older, though, I opened more doors in my life. Websites let me meet queer people worldwide, and as I started to expand out my friendgroups and meet new people in high school, I was able to use these two sources to better evaluate my own identity. I still mostly identified as bisexual, however I started to explore options amongst the demisexual or asexaul spectrum, thanks in part to my best friend at the time being demisexual. Meanwhile, when I started to meet trans people in real life, they were all transmasculine. At this time, I also distinctly remember, at least once or twice, thinking “man, I wish I was trans” because I wanted to be a girl. Even though I knew that being trans itself was not a mental disorder, I knew gender dysphoria was; without access to counseling services or some of the internet sites I do now, I didn’t want to self-diagnose myself with something like that. No one had ever told me that I needed someone to tell me that I was trans to be trans, but back then, I thought that was necessary for me to be trans.

This idea that’d somehow formed within me, undisputed because no one questioned it, made sure that I didn’t know I was trans -- or even really think of it -- until after I’d finished my first year of college. Back then, the only known aspects of my queerness was that confusion between if I was bisexual or asexual, and I’d been leaning towards the latter because I felt uncomfortable with the concept of me having sex. Because of this uncomfort, I’d thought for sure that I was ace -- but I was operating off of a flawed understanding of myself.

In the first year since I came out to myself as trans -- and to the world in the same moments -- I still maintained this confusion. Even still to this day, my sexuality is a bit of an enigma, but it occupies such a tumultuous spot in my life now for different reasons now. Now, my confusion is fueled in large parts by shame. A lot of it comes from my status as an “other”. Even in communities were trans people aren’t made fun of -- and as a kid, I was in a lot of communities where they were and jokes like “I sexually identify as an attack helicopter” were prevalent -- there is still an understanding of the difficulties faced by being transgender and the societal unacceptance that comes from it. As a form of “digital self harm” that I was almost unwittingly going about in the early days of my transition, I browsed subreddits that would make fun of transphobic people, but in doing so, I internalized parts of the transphobic rhetoric. I didn’t want to be one of “those” trans people, a so-called “transbian” or whatever (I personally find the name infantilizing) who was obsessed with wanting to be a catgirl, anime, and whatever, and so parts of me refused to want to admit that I wasn’t asexual or even bisexual. It made me feel even like I was less of a trans person at time -- so many “proper” trans women seem to be straight and feminine. I am anything but either of those two.

Though the trans suicide rate -- that 41% that people often talk about -- refers mostly to trans people who are denied the ability to transition and be respected (things I don’t face), it’s easy for me to see why the number is still so high. It is incredibly easy for you to find things that make fun of trans people -- if not being queer as a whole -- as part of a schema to keep society in line; after all, a society full of similar people functions better and through the oppression of those who are others that comforting familarity can be maintained.

But that’s why I am so flagrantly queer, and why I talk about it so much. So that people can learn from me, and so I can learn from others. I don’t want people to feel like they have to hide who they are out of a fear, and I want to stand in defiance to the societal forces that do make fun of queer people. It is through my own history of being scared and uncertain because I was never required to think much about who I was until I realized I was trans that makes me so keen and open to talk about it and be myself.

It is perhaps through the exposure to transphobic ideals, through exposure to people who wish to shock the gay away, that keeps me going. It’s a difficult battle, for at any moment, if I slip, I might not be able to get back up by myself. But for my own sake as well as the sake of anyone even somewhat like me, I must exist in conflict with these normative ideas of gender.

Plus, I won’t lie. It’s somewhat fun, existing in a state of confusing everyone with my own gender presentation -- if a little bit draining. Usually, though, it’s not as bad as it might seem.

0 notes

Text

Maps, maps, and maps.

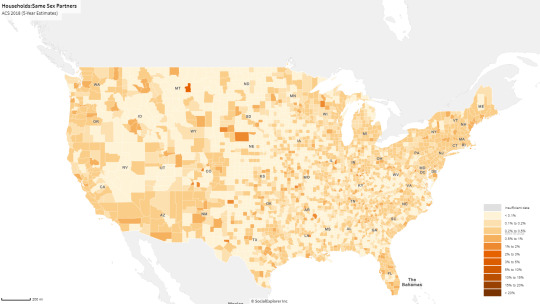

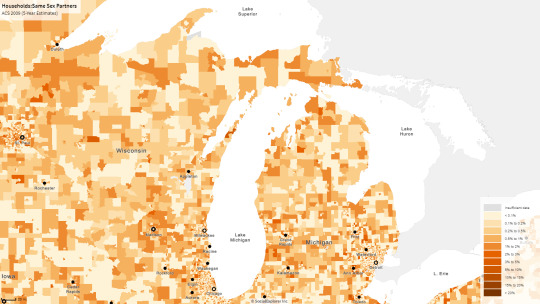

For some, it might be weird to think that it has only been five years since, nationwide, the Supreme Court of the United States mandated that same-sex marriage is legal across the country. At the same time, it can feel as though it was just yesterday; at the other, it can almost feel hard sometimes for some of the younger generation to remember a time in which it was not legal. As being part of the LGBTQIA+ community is something that I hold deeply important to myself, I thought it would be, at the very least, somewhat interesting to look into how many unmarried same-sex couples had existed in counties across America in six years before 2015 and then three years later, in 2009 and 2018 respectively.

In doing so, I decided to look at two areas for each year: one nation-wide, and one focused on Michigan and Wisconsin with a bit of Chicago and the Twin Cities included. My reasoning for this is simple: one can show more of a national trend, and one shows a trend more limited to the area that my school and my life has mostly occupied, and thus it’s a bit more personal for me to look at -- plus, with my better background knowledge of the area, it lets me more accurately theorize any patterns that I notice. All of these maps will show the percentage of unmarried, same-sex couples in a given area in compared to the total amount of unmarried households in that same area.

First, lets look at the nation-wide map from 2009, and then the 2018 map.

This is the 2009 map, on a per-county level. Next is the 2018 map.

Truth be told, there is some surprise to be had in the fact that the total number went down, but at the same time, it does make complete sense. After all, now that the couples could get married, they would obviously do so; however, the reason it was at least partially surprising to me was because I was somewhat curious as to if, because it was now more “acceptable” to be known as a same-sex couple, more couples would actually report themselves as such. Instead, what the data seems to suggest is the obvious: many same-sex couples did get married because they now finally did have the option to do so.

Now, looking at a more specific region, we can see the same trend on Michigan and Wisconsin:

Again, this is what it looked like in 2009, this time based upon the tract, and now what it looked like two years ago in 2018:

We see the same trend of the total number of unmarried same-sex partners in households going down. Now that we can look at specific tracts, we can even see areas where there were unmarried same-sex couples in 2009 that now have none at all in 2018. At this point, it is almost tempting to invoke Occam’s razor, and accept that, with the legalization of gay marriage nationwide in 2015 permitting these couples to get married, they just got married; however, there should be at least a few ideas noted that could also possibly influence these ideas.

A major problem, of course, is we have no way to tract where the people who had originally identified as being in an unmarried same-sex relationship wound up in the 9 years between the two studies. Some of them may have died, or broken up, or even moved. Some of these areas might have grown or shrunk population size, and thus the total number of bodies -- and thus, the ratio -- of people in the area as a whole changed. In addition, the survey these numbers are from poll just 3.5 million households a year; even assuming that each household is four people means that in the nine years between these two surveys, only 126 million Americans were surveyed from 31.5 million households, which is less than half our total population. It’s entirely possible that some people just didn’t get recounted.

But assuming that this is all a result of the 2015 Supreme Court decision, I feel this strongly correlates one thing: if you give people the option -- no, the right -- to do something on a national level, they’ll take advantage of that liberty that they deserve. It shows just how powerful that acceptance can be, and just how quickly people will take up those rights given to them, especially when they’ve been fighting for it for so long. Based off of the factors discussed before, we can’t assume a direct causation -- not off of this alone.

But I’d argue this is as close as we can get based off of just a map.

-Artemis.

Citations:

Households:Same Sex Partners [Map]. In SocialExplorer.com. (2009, ACS) Retrieved 12/28/2020 from https://www.socialexplorer.com/9f3b166f3c/view

Households:Same Sex Partners [Map]. In SocialExplorer.com. (2018, ACS) Retrieved 12/28/2020 from https://www.socialexplorer.com/a50be4dc8b/view

0 notes

Text

What’s this blog for?

Hello there! I’m Artemis. I’m a thirdish-kinda year college student at Michigan Technological University, located in the far north regions of, you guessed it, Michigan!

My Introduction to Sociology class has us, as a class project, posting things to a blog “for the greater world to see”, or something like that. Thus, that is exactly what this blog is for, partially because I am far too lazy to learn how to use any other blogging platform and, y’know, may as well use Tumblr as a result.

So here we are! My first proper post will be going up shortly. Cheers!

1 note

·

View note