Hi! My name is Anh Thy. I started to blog on this account firstly for the assessment, but secondly for writing my own opinion on the social issues.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Week 10 - Men Who Hate Women? The manosphere and gendered-based social media conflict

In the last discussion, I would like to discuss about an aspect of social media conflict: the conflict between men and women, or the ideologies of Manosphere and Feminism which has gone beyond mere dispute on social media.

From a random post

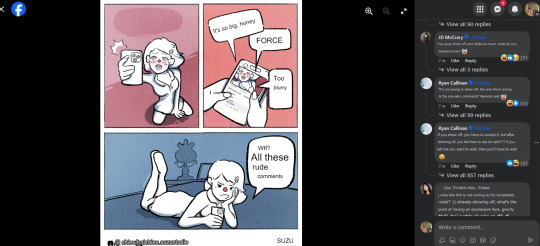

Recently, a well-known artist's Facebook account in Vietnam, Hai Chiều (translated as Two Way), which has been known for its art reflecting the societal issues in Vietnam, posted two photos, one is original, and the other is a a translated version. The photo portrays a young girl who posts her sexy photo and receives some rude comments on her pose and body which she does not welcome as her expression can show. However, this photo has received two kinds of opinion: one, mostly agreed by men, saying that since she posted this “kind” of photo on social media which means she voluntarily accepts and is open to harassing comments, and the other pointed out that this highly followed account is exaggerating the action (showing off sexiness and body) and unsatisfied expression of her face and intentionally distract the audience from the aspect of harassment in those reactions. The debate has not ended; however, what can be seen clearly is the idea of gendering conflict.

Facebook post: Hai Chiều's post

Figure 3: The post with the comments show their opposition to women and feminists

Haslop et al. (2021, p. 1420) indicated that online harassment includes spreading false rumours, sending abusive messages directly, and sharing personal content without consent, like intimate images, which constitute online hate crimes when they target specific aspects of an individual's identity, such as gender, sexuality, race, religion, or disability; in the context of the cyberhate targeted toward women like shown in the above case, Haslop et al. (2021, p. 1421) perceived that this kind of online harassment is the digital extension of the “physical forms of gender-based abuse and violence against women in society”. By encountering this kind of abuse, women, especially, young women tend to self-censor themselves online, faced with the silencing strategy as the harassment impedes the participation and digital citizenship of women online, and therefore, leads to the marginalisation and exclusion of women from online space, according to Haslop et al. (2021, p. 1421).

The underlying motivation

However, the underlying motivation of this cyberhate action might not just be the mere conflict between groups among social media users that can be solved by the community guidelines but the emergence of the Manosphere, an equivalent opposition to feminism in terms of ideology.

Marwick and Caplan (2018, p. 546), Manosphere refers to an online community comprising various groups like men's rights activists (MRAs), pickup artists, "men going their own way" (MGOW), incels (involuntary celibates), and father's rights activists who believe society is dominated by feminine values suppressed by feminists so that men must resist this perceived misandrist culture to safeguard their existence. As mentioned by Marwick and Caplan (2018, p. 546), one example of the conversation among this community is about issues like sexual violence discussed as gender-neutral problems, with the belief that feminists overlook or downplay sexual violence against men while also promoting false rape accusations. Although the Manosphere is arguably a place where the lost men feel belong, identifying a clear enemy, offering guidance, solutions to entrenched problems, and fostering hope (Rich & Bujalka, 2023). Nevertheless, among the community of the Manosphere, the term “misandry” is used firstly to address the discrimination against men, just like “misogyny” is the discrimination against women, according to Marwick and Caplan (2018, p. 554), but it is also used for a misogynistic purpose: to deny the existence of sexism. Specifically, Marwick and Caplan (2018, p. 554) address the core belief among the Monosphere community: feminism's key idea—that women face structural inequality due to patriarchy and sexism—is not just incorrect but deliberately lied and made by feminists who hold hostility towards men. As a result, harassment against women is weaponised by the MRAs as a means of defence against feminists and justifies the centrality of the victim narrative in the Manosphere’s members’ ideologies.

Finally, the discourse among the Manosphere community, which is mostly about the oppression of women and feminists can cause negative consequences. At the extreme level, Elliot Rodger, who perpetrated a mass shooting in Isla Vista, California, in 2014 could be taken as an example of hatred toward women kind of violence as most of his victims are killed as a punishment for rejecting his love (Dickel & Evolvi, 2022, p. 1392). In a less extreme scenario, those misogynistic discourses in the Manosphere community can easily lead to abusive behaviours, disregard for consent, and normalisation of misogyny as addressed by Dickel and Evolvi (2022, p. 1405). The solutions for that, however, are limited to criticising and blocking the website with misogynistic discourse, as well as empowering women and raising women’s voices to lessen the dangers of that content (Dickel & Evolvi, 2022, pp. 1405-1406). Moreover, there is also an idea about the soft power technique toward the Manosphere in which people use empathy, understanding, and patience to guide the lost men away from harmful parts of the internet and help them feel integrated into broader society (Rich & Bujalka, 2023).

In summary, the emergence of the Manosphere as a counterpart to feminist discourse has sparked societal debate. While it can serve as a refuge for men who need guidance for their lives, offering connection, and protection from perceived hostility, it becomes problematic when this community perpetuates hatred towards women and justifies harassment as a defence against perceived misandry. The Hai Chiều page exemplifies the extent of online harassment directed at women, predominantly by individuals associated with the Manosphere, potentially impeding social media inclusion, particularly for marginalised groups in society.

References

Dickel, V., & Evolvi, G. (2022). “Victims of feminism”: exploring networked misogyny and #MeToo in the manosphere. Feminist Media Studies, 23(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2029925

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018). Drinking male tears: language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568Rich, B., & Bujalka, E. (2023). The draw of the “manosphere”: understanding Andrew Tate’s appeal to lost men. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-draw-of-the-manosphere-understanding-andrew-tates-appeal-to-lost-men-199179

0 notes

Text

Week 9 - New Era of Gaming - The Era of Monetisation

The gaming culture within the era of digital transformation has experienced a significant shift that goes beyond the playful characteristic.

The live streaming and monetisation

Addressed by Taylor (2018), the emergence of live streaming goes beyond esports, reflecting wider changes in gaming culture. Platforms like Twitch have transformed gaming into a shared experience, where gamers of all kinds can engage with audiences in real-time, turning private play into public entertainment with interactive features like synchronous chat windows, surpassing the capabilities of traditional video platforms like YouTube before it enabled the live-streaming feature (Taylor, 2018). This shift in gaming central to the platform’s affordance creates new space for gamers to not only interact through broadcasting to small audiences of friends and family but also attract the mass audience with profitable practice (Taylor, 2018). Specifically, Taylor (2018) indicated that participants blend gameplay, humour, commentary, and live interaction, with some aspiring to professional status through various monetization methods. Therefore, monetising has become a noteworthy aspect of gaming in this digital era. Taking Twitch as an example, Johnson and Woodcock (2019) pointed out seven monetising methods that are mostly popular on Twitch, including:

Subscriptions: Viewers pay a monthly amount to a streamer for special username recognition.

Donations and Cheering: Viewers give money directly or through Twitch, with the platform taking a cut, but viewers receive automatic recognition.

Advertising: Streamers run adverts for corporate products on their channel.

Sponsorships: Streamers secure deals with game companies or brands for free products or promotions during broadcasts.

Competitions and Targets: Viewers are encouraged to participate in buy-ins for individual or global prizes.

Unpredictable Rewards: Drawing on the psychology of gambling, viewers donate in hopes of recognition.

Monetary "Channel Games": A gamified approach to Twitch's platform, engaging its user base with incentives for financial support.

Being one of the most prominent platforms for streamers to monetise their labour, Twitch’s position in this process is explained by the norm of Twitch’s users in which viewers consistently support their favourite streamers while aspiring streamers actively seek donations (Johnson & Woodcock, 2019). Therefore, Twitch's culture and infrastructure are deeply intertwined with money exchange, fostering a welcoming environment for new monetisation methods, and it also makes Twitch a community that fosters an audience accustomed to digital play, making them receptive to gamified approaches to monetisation.

But there is another way of monetising...

Another form of monetisation from the video game community is the in-app purchase with the potential of user exploitation. This has been addressed by King et al. (2019) stating that major video game companies have developed technical systems aimed at encouraging repeated in-game purchases, potentially in ways that could be perceived as unfair or exploitative. Specifically, these systems utilise player data to customise offers and purchasing opportunities, optimising them to incentivise in-game spending within dynamically evolving game environments, as pointed out by King et al. (2019). The example below of the 'Love Fantasy' can vividly depict how the monetisation is processed.

Figure 1: Love Fantasy's In-game purchase

As shown above, when the players lost the game, there would be a pop-up banner showing the invitation to use 900 purple gems to continue the pausing game. This is designed to be hard to win, and when the players use the gems to resume halfway through the game, it would be easier to win this level.

This, as criticised by King et al. (2019), potentially exploits player behaviour while leaving consumers with few protections and exposing them to financial risks, especially among underage players and their guardians.

Moreover, in the form of in-app purchases, free labour is also a part of it as due to their financial vulnerability, the users, especially young ones engage more in free social labour such as sending invitations to recruit gamers and sending hearts to increase usage in the example of Kakao game usage by young female users conducted by Lee and Seo (2023). The example above and given below also contain the invitation for free labour as the alternative for making the in-game purchase.

Figure 2: The Pop-up for in-game advertising in Love Fantasy

In the pop-up banner before starting to play, there is an option of 'Free Power' with a symbol of television beside it. The first picture in the example above also presents that symbol. As the players choose those options, there would be a video advertising playing around 30 seconds to one minute as shown below.

Figure 3: The In-game Advertising of Love Fantasy

Lee & Seo (2023) suggest that this free social labour is significant and often unconscious, impacting the financial dynamics significantly. As a result, to protect gamers, especially the adolescents who are more vulnerable in terms of finance and psychology as well as dedicated to gaming, from being exploited, King et al. (2019) suggested effective policies, interventions informed by psychology, and ethical game design principles are necessary to safeguard the welfare and interests of consumers.

In conclusion, the aspect of game streaming and monetisation can signify a new trend of media consumption and platformisation that media practitioners need to pay more attention to. Meanwhile, in-app purchases, despite lucrative advantages to the game producers, need comprehensive regulatory measures and ethical considerations to ensure the fair treatment and protection of consumers, particularly adolescents who are often the primary targets of such monetisation strategies.

References

Johnson, M. R., & Woodcock, J. (2019). “And Today’s Top Donator is”: How Live Streamers on Twitch.tv Monetize and Gamify Their Broadcasts. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511988169. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119881694

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Gainsbury, S. M., Dreier, M., Greer, N., & Billieux, J. (2019). Unfair play? Video games as exploitative monetized services: An examination of game patents from a consumer protection perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 101(101), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.017

Lee, C. S., & Seo, H. (2023). Being social for whom? Issues of monetization, exploitation, and alienation in mobile social games. Journal of Consumer Culture. https://doi.org/10.1177/14695405231195711

Taylor, TL 2018, ‘Broadcasting ourselves’ (chapter 1), in Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming, Princeton University Press, pp.1-23

0 notes

Text

Week 8 - Beauty filters and the pressure to be perfect

This week, the lecture and presentation have discussed the beautifying filters across social media platforms such as Snapchat and Instagram. The discussion goes beyond the instant benefits of filters mentioning that rather than building the self-esteem of the young women, those filters actually reinforce the narrow and unrealistic beauty standards with the embedded exclusivity.

Filters?

Firstly, it is necessary to explain what is the filters. Filters are the application of augmented reality (AR) technology which can add virtual elements and adjust facial features, allowing users to integrate augmented reality into their daily self-expression (Baker 2017, p. 208). This includes the functions of instant enhancements of the user’s selfies with various designs, including beautifying effects, distortions, and virtual accessories that follow the movements of the users in front of the camera, according to Baker (2017, p. 208). As a result, filters firstly can foster social connection through virtual accessories designed with a particular purpose, such as the filter of a community sharing the same interest or filter used for self-expression of identity as the examples given below (Penadés, 2023).

Figure 1: Filter designed for the community of Thai’s drama lovers

Figure 2: Snapchat’s Lenses (filter) for LGBTQ+ community

But, what's wrong with these cute filters?

However, as filters have quickly developed into a component of social media, it is also pointed out by scholars in the way they intentionally promote narrow and unrealistic beauty standards which cause psychological impacts on users, especially young women. Looking at the Flower Crown lens from Snapchat, one of the most popular filters on the platform, it is clear that besides the colourful virtual flowers, it also attaches with the distortion of the users’ skin to be brighter and smoother. Evidently, the filter is implied with the idea that skin needs fixing to be as bright and smooth as possible to reach the standard of being beautiful, and this filter is not the only filter promoting those kinds of beauty as given below.

Figure 3: The Flower Crown filter of Snapchat

Figure 4: The Instagram filter with makeup layout

In the article presenting Figure 4, there is a concern about body dysmorphia stemming from the increasing uses of beautifying filters, including the rising trend of cosmetic surgery-seeking with the motivation from those beautifying filters on the internet (Pitcher, 2020). The term “body dysmorphia” curated by Coy-Dibley (2016, pp. 2-3) into the “digitized dysmorphia” depicts that people who suffer from this disorder are usually dissatisfied and/or self-critique their appearance and try to alter their image to fit with some beauty standards, and the online beauty standard in the context of beautifying filters in this case. In other words, Robin (2018) indicates that the continuous comparisons of individuals between the real-life version and the filtered version, or with others on social media have negative consequences, especially on the mental health of young girls as they might feel their realistic imperfections can never qualify to be “beautiful” adhering the unrealistic and narrow beauty standards promoted by filters. This perception leads to the pressure to achieve the perfect image, insecurity about the issue of authenticity, and “guilt-ridded” satisfaction, which is addressed by Barker (2020, p. 209).

The problematic filters, as a result, cannot make their widespread popularity without the users who keep using and reinforcing those unrealistic beauty standards, but it is also necessary to mention the platforms or the people who make the filter accessible to the mass users (Barker, 2020, p. 217). Consequently, it indicates the influence of whiteness, non-inclusive, and unattainable beauty ideals aligning with the cultural biases of those creators and operators (Barker 2020, p. 210). Finally, even when users start to realise the cultural biases behind the platforms, it is hard to find the solutions for this phenomenon as the filters have become a significant component of platforms that most users would not likely give up immediately.

Temporary solutions

According to Barker (2020, pp. 217-218), some users do not stop using the beautifying filters but use them with caution and responsibility about their influences.

Moreover, Rivas (2024) adhering advice from a psychologist, Dr. Leela R. Magavi, a Hopkins-trained psychiatrist, suggests curating the feed with the content of positive motivation and self-kindness from influencers who promote authenticity and body-positive image as a solution to avoid the body dysmorphia from the beautifying filters with the narrow and non-inclusive beauty ideals implied.

In conclusion, the popularity of beautifying filters on social media platforms involves unrealistic beauty standards, particularly affecting young women's body image and self-esteem while filters are also celebrated for their functions as an instant boost of self-esteem and self-expression. While efforts to use filters responsibly and curate positive content help, addressing underlying biases and accessibility issues remains crucial. Moving forward, collaboration between platform operators and users is essential to promote inclusivity, authenticity, and self-kindness online, mitigating the harmful effects of these filters on mental health.

References

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016). “Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image. Palgrave Communications, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.40

Penadés, P. (2023). How Instagram and TikTok use AI in their filters to boost communities - FUTUREJOBS.AI. Www.futurejobs.ai. https://www.futurejobs.ai/en/blog/how-instagram-and-tiktok-use-ai-in-their-filters-to-boost-communities

Pitcher, L. (2020, April). Instagram Filters Are Changing the Way We Think About Makeup. Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/instagram-filters-makeup

Rivas , G. (2024). The Impact of Filtering on Social Media. InStyle. https://www.instyle.com/beauty/social-media-filters-mental-health#:~:text=Filters%20Can%20Affect%20You%20SubconsciouslyRobin, M. (2018, May 25). How Selfie Filters Warp Your Beauty Standards. Teen Vogue; Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/selfie-filters-warping-beauty-standards

0 notes

Text

Week 7 - Are those beauties realistic?

The lecture this week covered the topic of micro-celebrity practices on social media in contemporary times, detailing the process of monetization through visibility labour and the phenomenon of pornification that shapes the aesthetic templates adopted by many users, often reinforced by platform algorithms. Additionally, it explored how the heightened visibility of these aesthetic templates can contribute to concerns regarding body image.

How attention is monetised

According to Drenten et al. (2019, p. 42), the ability to monetise relies on the attention garnered by digital content. In the "attention economy," attention is a scarce and valuable resource that functions as a form of capital since once attention is measured, it can be marketised and financed (Drenten et al., 2019, p. 42). This has led to the emergence of "influencer commerce," where individuals create digital content to attract attention from a following on social media, often incorporating commodities into their everyday lives, and thus, influencer marketing on social media has become a multi-billion-dollar industry, with influencers predominantly being women who set cultural scripts adopted by everyday social media users, particularly on platforms like Instagram as depicted by Drenten et. al (2019, p. 42).

The problematic side of the influencers industry

Drenten et al. (2019, p. 42) noted that influencer marketing in the attention economy significantly reinforces conforming to heteronormative standards of attractiveness and femininity, often through sexualised self-presentation on social media. This aligns with the concept of "porn chic," where mainstream culture incorporates aesthetics from pornography (Drenten et al., 2019, p. 42). Ultimately, influencers aim to attract attention, gain likes and increase monetisation potential, with adherence to these norms being valued and attention-grabbing.

Some examples of those heteronormative standards in both masculinity, as Terry Crews, a sports player who is considered to work in a testosterone-fuelled environment, and femininity, as Kylie Jenner, who was described to have ideal beauty with exaggerated curves to their noticeably plumped lips below (Rix-Standing, 2018; Senft, 2013).

By continuously reinforcing the particular templates of beauty, for example, the template of Kylie Jenner as a perfect beauty standard for feminity, those templates would likely become a mainstream criterion of beauty that women "should" orient to. However, it could lead to a body image crisis relating to the unrealistic standards backed by the inequality in the way platforms’ algorithms choose what is to visible and what is not. According to Duffy and Meisner (2022), people of marginalised groups such as ones with queer identities or with ethnic identities would likely receive both formal and informal punishments from TikTok. As a result, there is evidently a bias toward what is normative and mainstream as well as excluding what is beyond it would directly lead to a crisis of body image for users who cannot adopt or are not naturally born with mainstream identities, including their appearance.

In summary, the rise of micro-celebrity culture on social media, driven by the attention economy and platform algorithms, has reshaped influencer marketing. While this has led to the monetisation of online personas and the establishment of cultural norms, it also raises concerns about body image. The normalisation of heteronormative ideals perpetuated by influencers can exacerbate insecurities and marginalise non-conforming individuals. As we engage with digital platforms, it's essential to critically assess their impact on societal perceptions of beauty and identity.

References

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2019). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12354

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2022). Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society, 45(2), 016344372211119. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Lang, C. (2023, July 28). Even the Kardashians Can’t Keep Up With Their Beauty Ideals. Time. https://time.com/6298911/kardashians-kylie-jenner-boob-job-beauty-standards/

Rix-Standing, L. (2018, November 19). Six male celebrities changing the conversation around masculinity. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/international-mens-day-2018-masculinity-mental-health-prince-harry-daniel-craig-dwayne-johnson-a8641256.htmlSenft, T. (2013). Microcelebrity and the Branded Self. In A Companion to New Media Dynamics. Chicester : Wiley.

0 notes

Text

Week 6: Slow Fashion and the Empowerment of Digital Citizenship.

In the lecture of week 6, we had a chance to navigate through one of the most mentioned topics among the global digital community, sustainability, with a focus on the Slow Fashion movement. In this post, I would like to briefly recap how the companies and consumers engage with the movement, the relation between digital citizenship and the Slow Fashion global effect, and an example of how Slow Fashion influencer create their influence within the digital community.

Fast Fashion

It is necessary to define Fast Fashion, or Fast Fashion consumer behaviour as a driver of the Slow Fashion movement. Fast Fashion is characterised by rapid production cycles that facilitate the creation of trendy designs, allowing consumers to constantly update their wardrobes affordably and conveniently (Balchandani et al., 2023). The consumer behaviour within this trend usually includes discarding garments after minimal use, with some estimates indicating that lower-priced items are treated as disposable, often being discarded after just a few wears (Balchandani et al., 2023). As a result, it caused a devastating environmental impact due to synthetic fabrics discharged by manufacturers to the waterways and the waste from massive consumption of fast fashion, along with the poor working conditions with low wages at the supplier factories (Oshri, 2019).

Slow Fashion as a solution

Emerging as a solution to the negative impact above, the Slow Fashion movement addressed by Domingos et al. (2022, p. 2) rose at the moment when consumers started to increase awareness about the impact of the fashion industry on the environment as well as the society, which leads to the support to the term ‘Slow Fashion’ in recent times. Furthermore, Domingos et al. (2022, p. 2) also indicated that ‘Slow Fashion’, and the demand for sustainable fashion overall, do not separate from being stylish but rather ‘sustainability’ creates a sense of ‘persona growth, well-being, and experiential pleasure’. Likewise, Domingos et al. (2022, p. 12) synthesised the research of other scholars about the Slow Fashion movement and briefly addressed five characteristics of Slow Fashion consumers: (1) authenticity; (2) locality; (3) exclusivity; (4) equity; and (5) functionality. By purchasing those sustainable products, Slow Fashion participants have a chance to satisfy those five characteristics mentioned above by adopting a positive social and self-image with their unique own styles rather than being trendy, purchasing with good environmental practices, fair trade, and supporting the local community, concerning about the workers within the fashion industry, and finally paying more attention to the durability of the products to avoid waste and pollution, according to Domingos et al. (2022, p. 12). In general, Slow Fashion is definitely not a temporary trend but rather a permanent factor that the consumer increasingly demands and requires companies to pay more attention and make a change to adopt more sustainable procedures in manufacturing.

How it goes viral

The Slow Fashion movement has increasingly grown with international influence in recent times while the Fashion Industry has been long established, it would be interesting to point at the trace of digital citizenship in the efforts of environmental activism to increase awareness about this long-standing issue of fast fashion pollution. One important concept within the digital citizenship definition is participatory democracy, addressed by Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 364), participatory democracy goes beyond just choosing leaders and government structures but is a part of daily life, including the activities such as actively expressing opinion and getting involved in personalised politics regularly. As stated by Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 365), personalised politics means that participants might raise their voices to the issues of specific individuals and/or organisations for more diverse reasons, including environmental issues like how the Slow Fashion movement participants have been doing. Adding to this, with the digital advancement of communication technology like social media, fragmented social lives with similar interests are connected enabling individuals and groups to gain political influence and drive societal change collectively, ultimately fostering larger and stronger social movement, according to Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 365). This sense of fostering community is also found in the Slow Fashion movement. The hashtag ‘Slow Fashion’ on Instagram solely has gained around 17,351,359 posts as the image below.

Figure 1: The #slowfashion hashtag

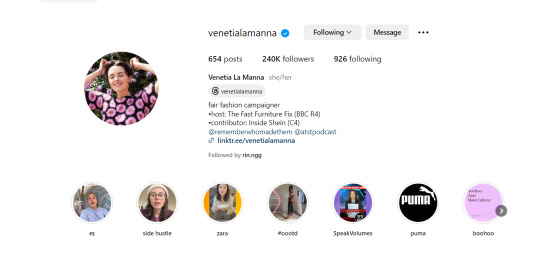

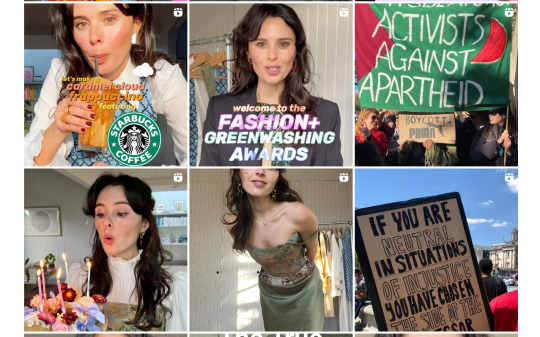

Even though this large number of posts means that the community seems to be scattered, there are still influencers within this community that take a role as a guide for the followers through social media. One example that I would like to introduce is Venetia La Manna

Figure 2: Venetia La Manna - a Slow Fashion influencer’s Instagram account

She is an active participant in the Slow Fashion movement with a diverse range of content on her social media with an attractive style of conveying her messages as a cooking recipe. Venetia does not only educate her followers about the impact and awareness of environmental issues but also points out the corporations that are doing the ‘greenwashing’, the act defined by the United Nations as misleading the public by exaggerating environmental efforts, promoting false solutions to the climate crisis that distract attention and delay genuine actions for environmental issue (United Nations, 2023). Moreover, Venetia also provides her followers with outfit ideas with Slow Fashion items in a way that expresses the sophistication, classic, and maturity that seems to satisfy the demand for social and self-image of consumers mentioned above.

Figure 3: Venetia’s content

In conclusion, it is clear that the Slow Fashion movement has attracted great attention from the public, and also accomplished several achievements as fashion giants like H&M and Zara started to reorient their products to sustainability. Digital citizenship and the influencers on social media, therefore, have a key role in this movement to educate, raise awareness, and make the move to mobilise the collective actions toward the companies/organisation so that Slow Fashion has actually become a movement and a permanent concern for the Fashion industry companies rather than a short-term trend.

References

Bakardjieva, M., Svensson, J., & Skoric, M. (2012). Digital Citizenship and Activism: Questions of Power and Participation Online. JeDEM - EJournal of EDemocracy and Open Government, 4(1), i–iv. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v4i1.113

Balchandani, A., Berg, A., D’Auria, G., Magnin-Mallez, C., & Simon, P. (2023, December 7). What Is Fast Fashion and Why Is It a problem? | McKinsey. Www.mckinsey.com. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-fast-fashion

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital Citizenship with Intersectionality Lens: Towards Participatory Democracy Driven Digital Citizenship Education. Theory into Practice, 60(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

Domingos, M., Vale, V. T., & Faria, S. (2022). Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(5), 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860

Oshri, H. (2019). Council Post: Three Reasons Why Fast Fashion Is Becoming A Problem (And What To Do About It). Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2019/05/13/three-reasons-why-fast-fashion-is-becoming-a-problem-and-what-to-do-about-it/?sh=2eda3af5144bUnited Nations. (2023). Greenwashing – the deceptive tactics behind environmental claims. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/greenwashing

0 notes

Text

Week 5 - Digital Citizenship, Platformisation and the example of hashtag publics

Within week 5, the lecture and presentations discussed a broad topic that mainly emphasises the critical role of digital transformation with the emergence of social media platforms. This came up with three main concepts that I would discuss in this tute: digital citizenship, platformisation, and how these two concepts have facilitated a place for the activism to rise through the example of the #SayHerName movement, a hashtag activism that involves the concept of intersectionality along with the digital citizenship and facilitated with the platformisation.

Firstly, Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 363) have introduced the definition of digital citizenship with a multidimensional approach including 5 dimensions: Skills in technology, awareness on both local and global levels, networking capabilities, critical perspective, and engagement in Internet political activism. However, Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 363) emphasised another critical aspect of digital citizenship which is embracing the marginalised groups who are usually denied the full rights of citizenship in society, such as people of colour, minors ethnicity, people who are discriminated against due to gender, sexual orientation, or religion; moreover, the inequality in the discourse of traditional citizenship, Internet, and social media was challenged by the critical and radical approach to the definition of digital citizenship by Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 363). In conclusion, Choi and Cristol (2021, p. 363) indicated that research and education in digital citizenship should highlight the critical connections between social relations and technology, fostering practices that empower and contribute to social justice.

Speaking of social justice relating to technology, the intersectionality framework is also important in this concept since intersectionality involves the concept that various identity attributes, including gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and age, concurrently influence and construct complex inequalities across social determinants, as defined by Collins (cited in Choi and Cristol 2021, pp. 363-364). Digital citizenship and intersectionality, additionally, can be a part of the participatory democracy, which is addressed by Choi and Cristol (2021, pp. 364-365) as a status achieved by expressive participation, for example, to discuss a political issue with people around, and personalised politics, for example, to talk to brands, corporations, or transnational policy forums with more diverse reasons based on personal experience. This can be seen as the nexus of intersectionality and participatory democracy in the way that social media allows those users to find topics or activism that align with their own experience.

Secondly, the platformisation is also mentioned in the lecture this week. According to Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Fletcher (2023, p. 485), platformisation is the step-by-step and diverse penetration of economic and infrastructural extensions from online platforms into various parts of the economy and everyday life; Helmond (2015, p. 1) also mentioned the term ‘platformisation’ as an extension of social media as well as how they render external web data compatible with the platform. Helmond (2015, p. 4) has indicated that Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) a key to the transformation of social media from network sites into platform; indeed, Helmond (2015, p.4) shows an example of how APIs were used to integrate external websites and apps, Tinder in particular, to Facebook or to add the ‘Like’ button of Facebook into their own page (as attached below).

Figure 1: Social media link to external website

Within that extension of social media, political engagement has been encouraged throughout the social media platforms. For example, social media in the election campaign is considered as an efficient platform for engaging voters, conversing with constituents, exchanging information and political perspectives, and fundraising which enhances the effectiveness of political campaigning, and perhaps directly impacts election outcomes, as indicated by Nelimarkka et al. (2020, p. 1).

As a result, social media also offers a platform the digital citizenship with an intersectionality framework to facilitate activism. One example of this concept is the movement #SayHerName launched in 2014 with the main goal to raise awareness about the invisibility of names and stories of Black girls and women who were victimised by racist policies (African American Policy Forum, 2014). Besides the offline activities, the usage of hashtag #SayHerName is still popular with recent updates and extending to more groups in society such as people in the LGBTQ+ community, as the images below.

Figure 2: #SayHerName media on X

Figure 3: #SayHerName hashtag with the Intersectionality

As indicated by Vicari et al. (2018, p. 1236), a hashtag public is a community on social media, X (Twitter) in particular, formed to respond to emerging issues or events with political relevance and connected through hashtags. The #SayHerName community on Twitter has also formed around the hashtag, and its official account also links with the official website for detailed information about the issues of violence toward Black girls and women, which can indicate the platformisation of a whole campaign itself. Last but not least, the #SayHerName movement does not only represent digital citizenship through promoting participatory democracy with expressive participation and personalised politics of the participants, but the intersectionality framework is also emphasised as the campaign, originally, fought for the Black girls and women, who might suffer the discriminations in both their race and gender that hinder their ability to perform full right of citizenship.

In conclusion, the concept of digital citizenship has been advanced thanks to the emergence of social media platforms, which have been extending throughout the platformisation process. Along with the platformisation, there would be more opportunities for people in marginalised groups to acquire and perform their digital citizenship in order to make their voices heard through activism and hashtags public.

References

African American Policy Forum. (2014). Say Her Name. AAPF. https://www.aapf.org/sayhername

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital Citizenship with Intersectionality Lens: Towards Participatory Democracy Driven Digital Citizenship Education. Theory into Practice, 60(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

Helmond, A. (2015). The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080

Nelimarkka, M., Laaksonen, S.-M., Tuokko, M., & Valkonen, T. (2020). Platformed Interactions: How Social Media Platforms Relate to Candidate–Constituent Interaction During Finnish 2015 Election Campaigning. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 205630512090385. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903856

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, & Fletcher, R. (2023). Comparing the Platformization of News Media systems: a cross-country Analysis. European Journal of Communication, 38(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231231189043Vicari, S., Iannelli, L., & Zurovac, E. (2018). Political hashtag publics and counter-visuality: a case study of #fertilityday in Italy. Information, Communication & Society, 23(9), 1235–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2018.1555271

0 notes

Text

Week 4 - Reality TV in Social Media era

Reality TV has been in a variety of debates on its nature, whether is it good or bad, fame or shame, and usually, reality TV is considered low-brow entertainment but also attracts a significant amount of viewers. Professor Danielle, a sociology professor at Lehigh University, views reality shows as a fun-house mirror that reflects ourselves, the audience who are mostly ordinary people in an exaggerated or amplified representation and addresses the active role of the audience through their social media engagement and voting (Joy, 2022). Furthermore, along with the emergence of social media, the participatory culture is also advanced by reality TV producers that not only change the way how the shows and their participants act but also the way the audience can affect the show through the example of Love Island, a UK reality show.

Firstly, social media has made a big impact on how reality TV perform, especially in the opportunities to have real-time interaction with the audience, extend the popularity, and also support the reality TV stars after the program. Social media, especially X (or Twitter) has definitely become a place where people perform the activity of a “communal event”, or more specifically, come to watch reality TV altogether, including the audience, producers, hosts, experts and participants, addressed by Deller (2019, p. 157); in this, this real-time and collective reaction through social media perform the “liveness” to reality TV that can unite the society and gather different generation in both personal and technology pattern to share the attention about a problem altogether, according to Deller (2019, p. 156). Moreover, the sharing of memes and GIFs broadly thanks to social media, which is mostly associated with the humour aspect of reality TV itself as indicated by Deller (2019, p. 158-159), could extend the popularity of the shows even when the shows have ended, for example, the meme of Gordon Ramsay in the Hell’s Kitchen; however, Deller (2019, p. 158-159) also proposed that two worth noticing things are that sometimes, the humour shared by the digital public might not be in-line with the humour that the reality TV producers want to oriented which can cause tension, and the memes themselves have their own stories that might go beyond the original context. Finally, Deller (2019, pp. 159-164) depicted how reality TV stars can benefit from the show in the era of social media. Using social media is a part of promotional strategies for the long-term career of the former participants, for example, the skill-based show contestants can elevate their business, or the vehicles for upcoming initiatives such as promoting the Drag culture in the case of RuPaul’s Drag Race stars, or to inform the upcoming activities that retain the attention of the audience to those celetoids after the shows, according to Deller (2019, pp. 159-164). Although social media can be a double-edged sword as the representation of a person on the show and social media may be “evil-edited’ and not true to their real personality, social media can also be a place where truths are revealed by the insiders, or simply to represent themselves in the way those insiders choose to instead of being chosen by the others, as depicted by Deller (2019, pp. 159-164).

Last but not least, it is necessary to mention the role of the audience within the social media era. Moving beyond the old and heavily regulated format of reality TV interaction in the past, the audience at the moment, for example, the Love Island show strategically utilises platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and its mobile app, requiring a basic level of digital competency from viewers to actively participate in shaping the show's narratives, according to L’Hoiry (2019, p. 7). L’Hoiry (2019, p. 7) also indicated that social media engagement with the show demands an implicit investment from the audience, encouraging them to vote for their favourite contestants, participate in quizzes, discuss controversies online, use official hashtags, and follow the show’s social media accounts. As a result, not only the audience is empowered to shape the shows the way that they want to, but in fact, their investment in engagement with the show online is a limitless source of monetising, including the money for voting to the ‘advertainment’ in which the show itself is already a vehicle for the advertising to be spotted, the significant visibility of sponsors through the mobile apps, and the collecting of users’ data, as addressed by L’Hoiry (2019, p. 3). Those have depicted a new picture of reality TV in the context of the social media era in which the producers and sponsors need to review and re-design their own strategies that can ultimately attract audience engagement and utilise the potential from those engagements with ethical considerations.

References

Deller, Ruth A, (2019) Extract: 'Chapter Six: Reality Television in an Age of Social Media' Download 'Chapter Six: Reality Television in an Age of Social Media'in Reality Television: The TV Phenomenon That Changed the World (Emerald Publishing).

Joy, J. (2022). It’s Time to Start Taking Reality TV More Seriously. Columbia Magazine. https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/its-time-start-taking-reality-tv-more-seriously

L’Hoiry, X. (2019). Love Island, Social Media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of Challenging Realism in Reality TV. Frontiers in Sociology, 4(59). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059

0 notes

Text

Week 3 - How Tumblr, feminism, and a mindful revolution of social media users.

#MDA20009

In week 3, we discussed how social media, Tumblr in particular, has become a critical space for the challenges against the ideal standards of beauty and misogynistic ideas about women as a part of the fourth wave of feminism. Looking at the larger scale, Tumblr became a safe space not only for feminists to find their like-minded people but also for people in other marginalised groups to have a sense of belonging to a community online through the use of hashtags, a platform affordance of Tumblr. Consequently, this week's discussion will point out the movement as an example of users leveraging the platform's affordance and vernacular to raise their voices and make activism, focusing on the feminist movement, #bodypositive, and Tumblr.

Firstly, the discussion turns to the #bodypositive movement on Tumblr in 2012 as an example of social media as a new battleground for feminism. As indicated by Reif et al. (2022, pp. 5-6), the hashtag #bodypositive became popular across social media platforms such as Instagram and Tumblr in early 2012 associating with the Fatosphere, where fat individuals and their allies seek acceptance, empowerment, and a sense of belonging while engaging in discussions about political and social issues; this hashtags along with the others such as #effyourbeautystandards, #beautybeyondsize, and #curvygir were used to promote the acceptance and reframe the constructions of fat and the fat body, according to Reif et al. (2022, pp. 5-6). Following this, the movement generated a level that aims to challenge the traditional and narrow concept of beauty and diversify. It consequently empowers and encourages women of different classes, ages, races, and sexualities to find their beauty, embrace their imperfections, and have a more positive body image (Reif et al., 2022, p. 6).

Central to this movement is the platform affordances of Tumblr that the participant leveraged to create a true digital community that is considered safer and more anonymous, especially for groups like feminists or LGBTQ+. According to Keller (2019, p. 4), the term ‘affordance’ can be understood as the features that are integrated into the hardware and software of social media platforms, constraining particular ways in which users interact and participate; further, Keller (2019, p. 4) also indicates the term platform vernacular, which is the users' experiences and perceptions of technologies are shaped by affordances. Based on those terms, the platform affordances and vernacular of Tumblr have been addressed significantly in how it can accommodate an inclusive online community that can raise the voice of the marginalised group. and activism. Pointed out by Rief et al., 2022, pp. 6-7), Tumblr, before 2018, had a particular openness to NSFW (Not Safe For Work) content that is usually disapproved by the community guidelines in other platforms such as Facebook or Twitter, not to mention the possibility of being the victim of “slut-shaming” and “victim-blaming” for posting selfies. Moreover, the visibility of the posts using hashtags on Tumblr does not relate to the popularity of the users, participation in the community, and reactions to the post, thus it provides an equal chance for many voices to raise within this online community, according to Rief et al. (2022, p. 7). Furthermore, in the research about the usage of Tumblr by the LGBTIQ+ community indicated by Byron et al. (2019, p. 2255), Tumblr is considered by the participants of the survey as a platform that fosters emotional sharing and learning, providing a safe and relatively anonymous space for diverse expressions, particularly through the interweaving of various content strands on issues such as gender, sexuality, mental health, body image, racism, politics, and feminism. Finally, Keller (2019, p. 9) pointed out the other affordances of Tumblr, which are the ‘de-prioritizing of searchability’ to the Tumblr profile and the control of users on the interactions with others that ensure the ‘social privacy’ for the users; as a result, this example also leads to a platform vernacular that the users in the research, the young feminists, are aware of the platform affordances and strategically apply this understanding in their usage of social media, particularly in whether they should post on Twitter or Tumblr based on the content (Keller, 2019, p. 9).

As a result, it is easy to see that the platform affordances of Tumblr, including anonymity, hashtag, independent visibility, and a considerable quantity of control over social privacy are the key to the outstanding position of Tumblr for the movement of feminism, LGBTQ+, and other communities that urge to raise their voices.

References

BYRON, P., ROBARDS, B., HANCKEL, B., VIVIENNE, S., & CHURCHILL, B. (2019). “Hey, I’m Having These Experiences”: Tumblr use and young people’s queer (dis)connections.. International Journal of Communication (19328036), 13, 2239–2259. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=ufh&AN=139171821&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=swinb

Keller, J. (2019). “Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms. Social Media + Society, 5(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119867442

Reif, A., Miller, I., & Taddicken, M. (2022). “Love the Skin You‘re In”: An Analysis of Women’s Self-Presentation and User Reactions to Selfies Using the Tumblr Hashtag #bodypositive. Mass Communication and Society, 26(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2138442

1 note

·

View note