Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

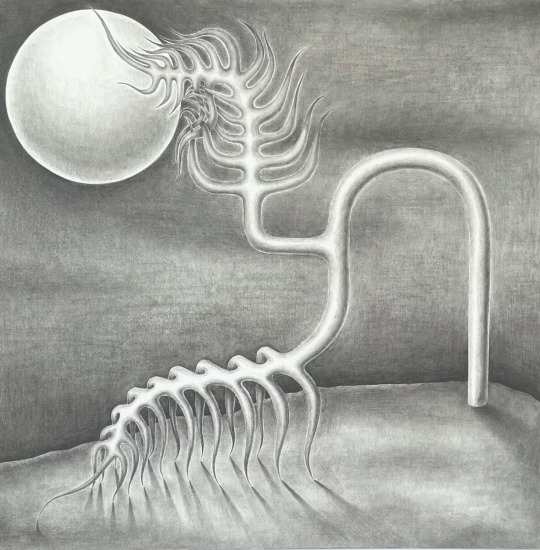

limb progress by devra fox, 2020, graphite on paper, 11 × 11 inches

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Brazilian Heroes: More Likely For a Snake to Smoke a Pipe

Very few groups of soldiers get the recognition that they deserve, even fewer are the men of colour who fought, bled, and died for the end of genocide and fascism.

It was said that it would be more likely for a snake to smoke a pipe than it was for the Brazilian Expeditionary Force to go into combat, but when they did, they left with a legacy that would last a lifetime, even if they are pushed aside and pushed down in favour of more white groups. The names of Geraldo Baeta Da Cruz, Arlindo Lúcio Da Silva and Geraldo Rodrigues de Souza swept under the rug and forgotten.

November of 1944 brought the Allied plans to liberate Italy from fascist rule for the second year in a row; for months, the fighting had resulted in pushing back the Nazis. The Allied forces had been made up of three dozen different nationalities - including British, Indian, Greek, South African, Canadian, and Nepalese (specifically, Gurkhas). However, one of the three dozen was one that nobody had expected, or even considered to think about: Brazilian.

25, 000 Brazilians had made up the soldiers and pilots of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, originally made for political necessity but now thrown into a war on foreign lands; they were the Smoking Snakes, named such after a popular saying: "Mais fácil à uma cobra um cachimbo fumar, do que à FEB embarcar", which translates to "It is more likely for a snake to smoke a pipe than for the FEB to go into combat."

In 1939, nobody thought that President Getúlio Vargas would be a key allied leader; originally, Brazil had possessed a largely outdated military, as well as a very active community of Nazi sympathisers and a lot of tension with Argentina. Vargas, however, wanted to turn Brazil into a unified power, and in 1942, thanks partially to Pearl Harbour and Franklin's pressure on other nearby countries to join the U.S.'s fight, Vargas made the decision that "Brazil must now stand or fall with the United States".

Vargas would offer Brazil's resources and land at first, and eventually, would create a combat force to be sent to Europe; at the time, Brazil was not prepared or able to cope with a war, but Franklin's pressure and iron fist had proved too much, and Vargas had caved.

General João Batista Mascarenhas de Morais was in charge of the Brazilian Expedition Force (the F.E.B.), and at 61, was the oldest divisional commander on the Allied Force's side in Europe; the F.E.B. was soon brought to American standards, and because it took so long for them to recruit, organise, train and negotiate overseas deployment, a new saying was brought up: "a cobra vai fumar" - "when snakes smoke".

Outdated equipment, reserve officers who weren't tested, and outdated half-learned French doctrine, the Americans turned their nose up at the F.E.B.; they hoped to stash them away somewhere quiet, instead of offering them a chance to show their metal. But Vargas had a secured promise that his men would see combat, and would be sent to war; the first batch of troops left Rio de Janeiro shortly after D-Day in 1944, brandishing the smoking snake on their uniforms.

The North African campaign had ended shortly before they could get to Naples, but by then, the Americans had found a quiet spot to hide the Brazilian forces; fascist Italy was ready to be collapsed, and the Nazis were localised to the North. The Americans thought, if they hid the Brazilians there, then they could continue serving as tokens and little else.

A baptism of fire was about to begin, and in September of 1944, the Brazilians were encroaching on Tuscany at the Arno River; it was here that they would truly show what they were made of. Not many men had served before, and even fewer officers had seen combat since the Brazilian Revolution; from September until the harsh winter set in, the Brazilians fought the Nazis and the Italian fascists as hard and as fierce as they possibly could.

At the same time, the other Allied high command was trying to find a way to make a push on Northern Italy in Spring 1945, hoping that they would take control of Bologne and capture it; in order to do so, it would mean having to secure northern Tuscany for its high ground. In the winter of 1944, going into 1945, the Brazilians were sent off to fight in the mountains; with temperatures going below -20°c, it was a harsh battle to even consider fighting, and with the added pressure of some of the soldiers never experiencing snow before, it was a fight that most would give up immediately.

But they didn't.

Difficult terrain meant that the Brazilians were at a stark disadvantage, but they still went out and fought the Nazis at the heavily defended Monte Castello; they were sent out on combat patrols during the night, where they would infiltrate the Nazi lines and test and probe the defences as well as take prisoners.

In 1945, the campaign begun, and Operation Encore was birthed; combined American and British offensives were tasked with trying to push the 10th and 14th Nazi armies out of Italy for good. The Brazilians, who were there to support the Americans, sent out their entire division for such a daunting task; their target was to attack Montesse, where the Nazis had a strong point in the south of Po Valley. The attack was set for April of 1945, and the Brazilians would take the left flank of the American side.

Before the attack, however, Brazil sent out patrols yet again; they would reconnoitre the heights, and the villages that surrounded the city. On top of that, they would clear minefields and make changes to maps to anything that needed updating; but the Nazis were also planning and were lying in wait.

On the 14th of April, 1945, right before the main attack was to take place, a patrol of three men was sent out; Geraldo Baeta Da Cruz, Arlindo Lúcio Da Silva and Geraldo Rodrigues de Souza were chosen for such a fateful patrol, unaware of what was waiting for them. Part of the Mountain Infantry, Geraldo Baeta, Arlindo and Geraldo Rodrigues were ambushed.

Originally spotted by the Nazi machine guns, they ran for cover and tried to find somewhere to get to safety; knowing that they were heavily outnumbered, they realised that they could not get reinforcements on their side whatsoever, and could not surrender no matter what.

Geraldo Baeta, Arlindo, and Geraldo Rodrigues knew that they only had one choice; they returned fire on the Germans, using everything they could until they had no more left, and the mortars began to drop around them harshly.

Knowing that they could not back down, the three men fixed their bayonets, and advanced; they were all immediately killed.

Geraldo Baeta Da Cruz, Arlindo Lúcio Da Silva and Geraldo Rodrigues de Souza were recognised for their bravery, and although they were not the only Brazilians to die that day, they left behind a fighting spirit; they died to save the lives of others, to end fascism. They fought against Nazism and Nazis with all that they had, and although snakes don't smoke, the three Brazilian heroes most certainly made the ultimate sacrifice for the end of genocide.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mohammed Sami (Iraqi, 1984), Nocturnal Animals, 2023. Mixed media on linen, 45 1/4 x 53 1/8 in.

828 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Filip Custic explores transhumanism in ‘Human Product

423 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annika Tucksmith (American, 1995) - Untitled (2024)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

They Have Slept in the Forest Too Long (1926) Max Ernst, oil on canvas

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Doctor Johannes Faust, Magia naturalis et innaturalis, 1849

825 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swamp of desires (((demo)))

1 note

·

View note

Text

Marin Majić (German, 1979) - Behind the Bend (2023)

784 notes

·

View notes