Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Continued: Eight Impressions from Albania

<Part 1 of this post is here>

Journeys

I had started in the port town of Saranda, on the south West tip of the country, half an hour by boat from the Greek island of Corfu, one of only a handful of ways to enter Albania. A town of cheap mussels freshly-caught and cheaper backpacker lodges, from which there were two roads out: one snaking up the coast towards Vlore, and the other East, across hills towards Gjirokastra and Permet.

I took the route east, going first to Gjirokastra and its hillside of Ottoman-era landowner houses, the birthplace of the great Albanian historical novelist Ismail Kadare, where I spent a couple of days wandering, and then on to Permet to meet Cimi. The terrain was not insurmountable, but still it held the upper hand and told you how you had to proceed: gently, in daylight, towards the next pass, the next trough between the ranges, the next crossing where the mountains dipped. So that an as-the-crow-flies distance of 10 km would become fifty or seventy on the road, and two and a half hours or more on the unhurried buses.

Bus stations were no more than a clearing in front of a centrally-located shop or cafe, and buses advertised their route by way of the driver screaming out place names. Once the driver had hustled enough people into his seats the journey would begin along the river valley, the passengers mostly quiet but not the bus itself, which played music or videos of alternately lilting and gyrating Albanian folk music.

Flat ground is precious in this mountainous country, and our bus would soon leave the coastal plain or the valley and begin crawling up the mountainsides. Then around one of those hair-pin bends it would screech to a sudden halt at a turning. Turn around and peer out and you would find that this was where one or more mule-tracks met the road. Here one or two patiently waiting men would swing into action, unloading a crate of spinach or cherries or a sack of grain off the back of a mule or donkey, loading it up into the back of the bus or hoisting it onto the last row of seats, with instructions to the driver to unload it at a waiting mule at the next town along.

An unfamiliar sight in modern Europe maybe but familiar to me, reminiscent of the once-a-day buses that wind their way through the mountain villages and tea estates of the Western Ghats near where I grew up.

--

I reached Permet the afternoon before our 5-day hike was due to start. It was, looking one way, like every riverine mountain town from where treks begin: where one arrives the afternoon before, looks anxiously for shops to purchase last-minute supplies, breathes a sigh of relief to find them, looks for a more-elaborate-than-usual sitdown meal at a riverside eating house, and spends the rest of the evening in a quiet thinking of what is to come.

For five days Cimi and I walked together in the mountains and valleys around his hometown. Along the Zagoria valley, unconnected by road, on that first day to Limar, then across the mountains and down towards Permet in the valley of the Vjosa river on the second. Into a designated National Park of Macedonian-native fir trees called the Bredhi i Hotove on the third, he deftly ensuring (in spite of our liimited shared vocabulary) that we kept up a loud-enough conversation to keep the bears away. On the fourth morning along the Vjosa again on the other side of Permet, crossing an Italian-era bridge to the village of Petran, stopping at some thermal springs for a dip before a steep climb to the beautiful mountain village of Benje to spend the night. Then on the fifth day taking shepherd's-only trails across the low mountains back to where we started, Cimi expertly cowing down with the ferocious sheep-dogs that we encountered on the way.

Growing Pains

Over the next week as I made my way from village to small town to regional city to metropolis other things betrayed their familiarity too.

I had left the south for Berat, in the centre of the country. It had the feel of a regional capital and also of a past glory, with its snazzily-dressed old men out for their Xhiro - stroll - in the evenings once the sun had lessened in intensity.

By the river rose this neo-Classical building, standing taller than all others, at a scale and opulence out of place in the Albania I had seen so far:

It was home to the University of Berat. Finally! I thought, for one of the things that had begun to pique my curiosity was that I had not seen any evidence of an institutional or professional middle class of people yet. Now in Berat I would find an intellectual atmosphere that grows up around a University city: professors, artists, researchers, library cafes, students who would form the next generation of this group of people: maybe even young people in one of these cafes who could speak enough English to have an involved conversation with.

Only to be told that the University had been shut last year. Why? The reason was incomprehensible to the Danish girl sat next to me listening to the story but perfectly understandable to an Indian: a huge "pay to pass" scam had been unearthed in almost all the private universities that had mushroomed in the regional centres of Albania since the fall of Communism and the sudden rise of private enterprise. It was an open secret, but the scam had finally become too big to ignore, and a couple of years ago all these universities had been shut down. And now Berat, and small Albanian cities like it was back - at least for young people with higher ambitions - to how it used to be, and at 18 they had no option but to compete for limited places in the capital's public universities, or stay at home. Growing pains, and as I watched the young folk whiling away their time in Berat's riverside cafes I saw them differently after this.

"The News"

The long bus ride to Berat inland from the coast reminded me also of other Balkan journeys, in Croatia over the winter in a modern two-carriage train winding up from the beautiful coastal city of Split to the capital, Zagreb: six hours through a white, frozen country: fields, trees, shrubs, lakes and rivers all iced over with stalactites dangling. After skirting the beautiful Plitvice Lakes National Park we arrived in human habitation after what seemed like hours: this was the small hillside town of Knin. Amazingly my phone instantly picked up a 3G connection, so I decided to look Knin up.

“Before the Croatian War of Independence 87% of the population of the municipality and 79% of the city were Serbs. During the war, most of the non-Serb population was ethnically cleansed from Knin, while in the last days of the war the Serbs were killed or ethnically cleansed from Knin by Croatian forces”.

I closed the page shut, the train still on the platform. Gory stuff indeed, but that wasn't the only reason why I wanted to stop reading. There was something unfair about the whole business: that this town of Knin with its wrinkled old man bidding goodbye to his wife on the platform just now and its row of peculiar houses up the hill, being still associated so singularly on Wikipedia with this act of inhumanity of twenty-three years ago.

And in the smartphone age, of course, there are newer and ever more pointed ways of accessing the sort of thing that becomes news. And who wrote that article on Wikipedia? It is very difficult to imagine that it was a Knin local (of whatever stripe, Croat, Serb, or Bosniak). Who wants their own town to be committed to writing for the world to see in this way? How would a Knin local have described his town instead? That it has a beautiful Orthodox church at the top, that they once heroically resisted the Ottomans (a fairly unifying, common theme right across the Balkans I've learned), that there are two folk songs which have lines that mention the beautiful young unmarried girls of Knin? I wouldn't know, I am only guessing here, but perhaps something like this, with an addendum, in a low voice if such a thing can be represented in the cold words of a Wikipedia article, of the ethnic strife that once visited this town twenty years ago, and has now left.

It must have been for reasons such as this that I avoided reading or watching anything about Kosovo (an ethnic-Albanian majority state to Albania's north-west) during my time in Albania, even though I remembered it being briefly in the news earlier this year. The only time I heard Kosovo mentioned on this trip was a girl in a bar in Tirana, who said, "They're Albanian too, but because their communism was not as strict they're more exposed to other cultures than us. There is some great music there, You should go to Pristina and Prizren next!". I enjoyed hearing this positive impression of that country then, and when I do visit, I would much rather keep her suggested way of looking at Kosovo at the top of my mind, rather than images of past wars and present conflicts.

All Together

As we passed this riverside graveyard outside Permet I asked Cimi, "Is this a Christian cemetery or a Muslim cemetery?"

"Both", he said. "All together. We have no problem".

All through my trip there had been hints of this easy secularism and coexistence in this nominally Muslim-majority country. In the South where I spent most of my time a significant minority were Bektashis, a Sufi sect with its origins in Turkey.

Below a Bektashi shrine and mausoleum on the grounds of Gjirokastra castle. The South was dotted with these little shrines, as well as traditional Sunni masjids and orthodox churches. None of them, even in the bigger towns and even the Sunni ones during namaz, had anyone inside.

There is historical probable-cause for this: Albania's communist doctrine had banned religion, destroying mosques and churches ("One of the few good things that the Communists did", Cimi quipped), and encouraged a pan-Albanian identity. But even that does not fully explain this religious intermingling. In earlier centuries, with Ottoman conversions, when entire villages converted and re-converted to one or other Islamic or Christian sect often for purposes of protection and tax relief as much as religious calling, people were said to remember and trace back their historical clan-lineage more than their religious leanings. This too over the centuries kept religious difference at bay.

And now? Many people I spoke to, Shamsi the waiter, Cimi himself, self-identified as religiously liberal or atheist: usually spoken of just before downing a strong glass of Raki, or in describing their family: Cimi's wife is Orthodox, and his siblings' spouses fall on every side of the coin: Sunni, Bektashi, Orthodox Christian, Catholic.

They were familiar with global currents on this too, of Islamic fundamentalism around the world, and made the point of how they were flummoxed by it. And again, our limited shared vocabulary prevented a detailed discussion, but what they seemed to say was this: This is how we've always been. It is possible to be this way. In the rest of the world strange things are happening with religion. We find that odd.

Modernity

Time and again, people spoke of how they felt their country was 'backward', that 'things have to change', that there wasn't enough opportunity for them and they were forced to emigrate. It is difficult to argue that last point (remember the shut Universities up and down the country), but there is certainly modernity in Albania, modernity in its most profound sense. Take the story of Hoxha and his Bunkers:

Enver Hoxha took over as leader of Albania's one-party Communist state in 1944 and, over the next forty years, cemented his position as Supreme Leader. His brand of Totalitarian rule was too much not just for China (who broke with him in the early seventies), but even for the mother country the Soviet Union, who Hoxha condemned as deviated from the fundamentalist line. Over time he built all over Albania a series of these "spying posts", both above and below the ground, on streetcorners, hillsides, and nooks everywhere. Many of these still exist:

During the second half of his reign he built two series of underground bunkers in the capital city Tirana, one right underneath the Ministry of Defence and Parliament, and the other, more elaborate construction, complete with an underground Parliament Hall, a few miles away. They were built to withstand chemical and nuclear attack. I spent a few hours each in both, and they are masterpieces of claustrophobia, paranoia and stale air.

What is more incredible, though, is what has been made of these spaces in the years after the fall. Here is the entrance to this space, dynamited into the hillside:

What followed was a reconstruction and preservation of the highest order, encapsulating and committing to permanence and memory the worst excesses of the regime, and for the visitor without any loss of the eeriness.

Enver Hoxha's underground quarters:

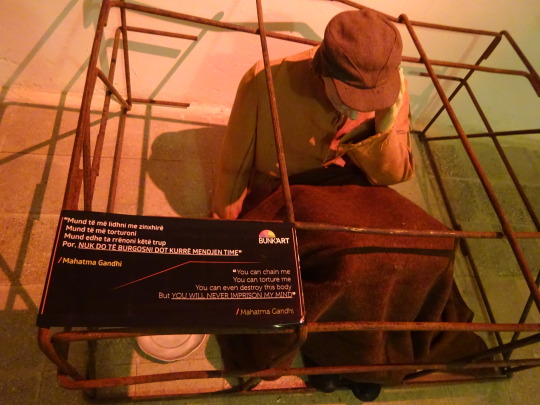

The preferred holding cell for dissidents and political prisoners:

The photographs are of those who lost their lives as part of the regime's political purges. A voice called out the names of the deceased.

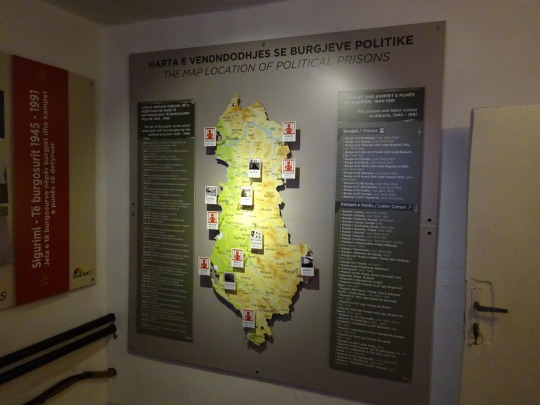

Political prisons and concentration camps were set up all around the country:

Dogs were trained to hunt, maim, and kill, to guard the borders:

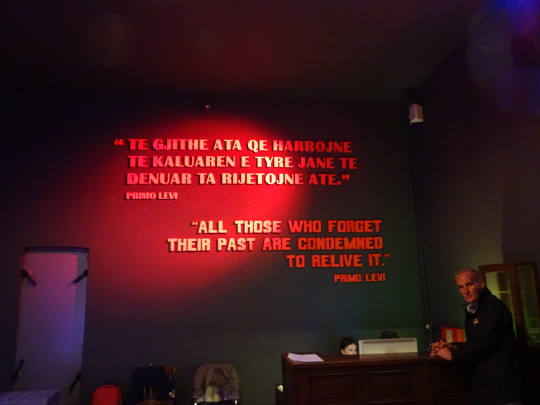

It is difficult to capture in photos how eerie the experience was. Often it seemed inappropriate even to click pictures.

I had read about the Bunkers even while in Permet, and asked Cimi if he had ever seen it.

"No, but I have heard about it. I cannot go. It is too painful for me".

Cimi wouldn't, but many Albanians were there on the days I visited. This museum-visit was no daytime stroll, neither was it entirely academic. The young, but especially the older, had a quiet intensity as they slowly made their way through the dank corridors. Some were close to tears.

I wanted to scream out when I emerged from the bunkers into the sunlight: This is modernity! This is progressiveness! A memorial to past mistakes and madnesses that many countries and people around the world - including our own - struggle to acknowledge even happened, let alone bring out with such forthrightness and honesty for themselves and the rest of the world to see. What a towering achievement Albania's Bunkart is!

Cimi

This is Sotir, Cimi's father-in-law.

A retired schoolteacher, he lives in the beautiful mountain village of Benje. We had trekked 17 km that day to reach it. We spent the night there. All evening he kept pouring the Raki, and kept bringing out the plates of cheese and salad to go with it, and kept the folk music playing loud on his battered old tape recorder, and danced.

And below, Cimi:

1 note

·

View note

Text

Eight Impressions from Albania

Limar

This is Mani, the forty-something schoolmaster of the village of Limar in the Zagoria Valley in southern Albania. Limar has 21 families still living in it, and, in the only school in which Mani teaches, 8 students. Cimi and I had reached Limar after an all-day hike along the valley of the Zagoria river, crossing it on a beautiful stone bridge that was built by the still-remembered local ruler from the early 1800s, Ali Pasha of Tepelene.

The school in which Mani teaches is just behind the church building in the foreground. To get to the nearest paved road it is either a trek of a few hours accompanied by mule or horse, or, for the few who are lucky enough to own or have access to a rugged Mitsubishi or Toyota 4x4, a rocky 90 minute drive through a ten-feet wide path rutted into the mountains.

In the winter when there is six feet of snow or in the rains in late summer when parts of the trail start washing off, those thin paths cut into the mountainsides become almost impossible to pass. Except for coffee beans and flour to bake bread which they buy in sacks and transport by mule from the nearest town at the start of every winter, the people of these villages are entirely self-reliant. Every house - including Mani's who put me up for the night - grows tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce, onion, white beans. They will also own a few sheep and perhaps a cow for milk, yoghurt, cheese, and only on the rare occasion, meat. Along the fences or on raised rods in the garden, vines of grape with which they will brew raki at the beginning of autumn, the strong local alcohol drunk in small shots - right from seven in the morning sometimes, as strong accompaniment to the day's first strong coffee.

Improbably on the night I was there, all of the above ingredients seemed in harvest. This was the meal Mani's wife had put together:

Mani's two children have left the village. In contrast to most families in the region whose next generation only manages to find unskilled, informal work in nearby towns to get by, his children have left for bigger things, their father's schoolmaster ethic behind them perhaps, to go to University in the capital Tirana, the son to study Finance, the daughter Teaching.

With the turning of time there would be one less family - at the very least - in the mountain village of Limar.

Cimi

"What will happen in the next generation, Cimi?", I asked as we walked on the next morning, leaving Limar's schoolmaster and its locked-shut church (more on that later) behind us.

"Village finish maybe", Cimi replied, without having to think too much about it. "Or maybe if proper road come...", although his shrug suggested that he thought that an improbability.

Indeed Cimi had been pointing out emptied-out villages and hamlets all through our wander across these valleys. Part of the reason for this emigration is to do with recent history: until 1990 Albania was behind the iron curtain and largely closed to the outside world. Part of the government's policies -- implemented via ID cards and endless check-points -- dictated that people had to live and die in the village where they were born. Cimi, now in his late thirties so until turning a teenager under Totalitarian rule, spoke of growing up in a family of ten children, in the winter not enough woollens to go around, his parents subsistence farmers whose surplus if any was bought by the state, and given little other scope for expanding their income.

When Communism fell in 1991, not only did many rural people emigrate to towns and cities, emptying out villages like Limar, almost a million out of the country's three-odd million went abroad, to the nearby countries of Greece and Italy first, later to Germany, the UK, and even America, far away.

Cimi though did not want to leave. He knew enough stories of friends and siblings abroad struggling for decent work and to be paid fairly that he decided to stay. He only had seven years of school: the minimum mandated under Communist rule. Then he became a shepherd, internalising every path and creek in these valleys. In Permet, the town where he lives and where I stayed for a few days, there are new houses coming up on the edge of town, most of which, he says, are being built by people who moved to Greece to work. In this remittance-driven construction opportunity he along with some of his brothers have found work as builders, and in the warmer months, a relative prize of 30 euros a day guiding tourists and hikers through his patch of the country.

Bidaai

Perhaps this Communist-era closedness became so internalised after a point, a self-fulfilling prophecy that gave rise to a self-censorship, that has led to keeping this small European country off the map even in the 21st century. In my fortnight there I did not see - apart from a few groups of German tourists here and there - foreigners of any sort until I reached the capital (and even there only a few), and certainly nobody of a different ethnicity. To say I stood out is an understatement. So imagine my surprise when while walking on the street I was greeted sometimes with shouts of "India - India!" and more often with "India - Bidaai, Bidaai!". What did this hindi-sounding Bidaai mean? That night at schoolmaster Mani's house after that sumptuous dinner I found out. I was called excitedly into their living room where this whole rural Albanian family, Mani, his wife, and his seventy-something mother sat glued to every subtitled word of a Zee-TV soap opera, complete with mother-in-law, daughters-in-law and servants in the background, improbably opulent house, ultra close-ups of fear and loathing all accompanied by a thunder-and-lightning background score.

"Bidaai!", the wife cried out to me as they made space on the sofa, pointing at the television and looking at me for reaction. "India!".

A quick perusal later of its wiki page unearthed this by way of synopsis:

“Sapna Babul Ka...Bidaai is an Indian soap drama that aired from 2007 to 2010 on STAR Plus. It tells the story of a father and his two daughters. Ragini and Sadhana are cousin sisters. Sadhana's father's only dream is to see her in the form of a bride. Living in the Sharma household, she manages to win over both Ragini's and Prakash Chandra's heart. However Ragini's mother, Kaushalya is hesitant to due the difference in skin complexion between the two”.

The whole family had by now turned to me, expectantly. "Yes, of course, Bidaai", I finally managed to grin in response. How could I not know it?! And so I watched an episode of Sapna Babul Ka...Bidaai in rural Albania, them hanging on every word of the Albanian subtitles and chuckling at the proceedings for the next twenty minutes.

--

Men of an older generation spoke equally about Raj Kapoor packing the movie houses. One night after many rakis and Gzuar!s the seventy-something waiter at the crumbling guest-house I stayed in in Gjirokastra, Shamsi, burst into a gap-toothed Albanian-accented rendition of "Mera Jhootha Hai Japani, Yeh Pathloon Englishthani ". He went on talk about how during Communist times most Western fare was prohibited, and Albania itself had no film industry to speak of. India - and China who were close ideological friends for a time - had provided a lot of this Balkan state's entertainment needs.

Not to say that a lone Indian traveller in 2017 is mistaken for someone from the movies or a television soap, but there was no doubt that these movements of the world had created in the minds of Albanians a positive impression of India and Indians, reflected in those cries of delight and recognition rather than negativity or suspicion as I walked along the streets of their towns and villages. I remembered my fortnight in Greece a couple of years ago, of facing intense glares and unfriendliness on the Athens metro. It took a day or two of wandering about to see that their associations of brown-skinned single men were of Indian and Pakistani illegal labour, scrap-pickers and asylum seekers walking the streets, increasing pressures - or so the perception went - on a country already in financial crisis. Hadn't the Greeks too enjoyed watching Raj Kapoor and Amitabh Bachchan once? They must have, but clearly those happy images of south Asians had been replaced by newer, less positive ones. --

Not that it never happened in Albania: it did, once. As I waited for a bus back to Gjirokastra one hot afternoon a shared taxi slowed down, then, the driver gesticulating with a wagging forefinger at me, came to a stop a bit further ahead. The kid waiting at the bus stop next to me got into the car with no problems, but as I started the driver stepped out to ask where I was going. Gjirokastra, I said. And where had I come from? England, Anglais. Indian from England. "No Anglais! No Anglais!", he said. Turisti, I said. I'm a tourist. "Kaa Turisti?!" he exclaimed, throwing his hands up, What Tourist?! He shook off his sunglasses and ran his forefinger along his cheek. "Anglais No!", he said again, You don't look like you're from England. Then with a final wave of both hands, he drove off. It left me feeling flummoxed. A racist, I thought, this man was being racist towards me. The shared-taxi had sped away and the road was now empty. I looked around, and spotted the sign for the village across the road: GORANXI, written in the Latin script that Albania uses, and below it the village's name in Greek: Καλογοραντζή. We were twenty kilometres from the Greek border, on a highway that led north to Tirana and further out of the country. This very stretch of road had probably seen its share of asylum seekers over the last few years, on their exhausting trudge from making landfall in Greece, through the Balkans and central Europe to the promised lands in the North: this same taxi driver had probably been asked, and now felt complicit or compelled to assist in getting them across this small country caught in the middle. I took the personal affront far less personally after realising this, rebranding the incident in my mind as one that was not quite, or far more than just a straightforward case of racism.

Different strains maybe, but the same global currents that had got me those shouts of recognition of "India! Bidaai!" had got me the cold shoulder from this taxi driver on the Greece-Albania highway. I got on the next bus which arrived five minutes later.

--

Continued here.

0 notes

Text

Glimpses in Podgorica

Montenegro is a country is nestled in mountains. The descent into Podgorica was spectacular if slightly jittery, as was this view from my balcony.

People have been warm and friendly - what a change from the calculatedness of England! - a man at the homestay saw me standing in the cold living room and immediately beckoned me into his den (he must have been a caretaker there) - "Come, come!" he said as he put more logs onto the fire and looked over again at me as he put his hands over it to warm up, beckoning me with his hands to do the same. Another man said "The centre of the world!" he responded when I said I lived in London. "Do you live here?", I asked him. "Yes unfortunately, I am a resident of this Podgorica", he replied, laughing somewhat bitterly.

--

Some Banksies, especially this work, are universal. I've seen this everywhere in London and Bristol (of course), but also next to Mahmoud Darwish and Baudelaire quotes in Marseille ("You gave me your mud and I made it gold"), and now here on a side street of a Balkan city, off Octobarske Revolucije, the Street of the October Revolution.

Google declares Podgorica to be a "practical", even "unattractive" city. Perhaps so if neo-classical and renaissance architecture and displays of wealth which you can find in many other parts of Europe is what you are after. But I came for these apartment blocks and these buses, these fading but still-glorious paeans to communism.

Along the main road to the city centre a sign led me to an unassuming residential neighbourhood, to these simple mosques from the Ottoman period. (The inhabitants of Montenegro famously held out, ensconced by the cold, hard mountains of the Dinaric Alps, and unlike neighbouring Bosnia did not convert to Islam).

-- Street signs are in up to three different scripts - Cyrillic, Greek, Latin. Signs of having been at the crossroads - or in the spheres of influence - of different cultures.

Another man who walked with me awhile when I asked him for directions from the bus station had this to say on the subject (without me asking): "I don't like English. I am not a fan of capitalism. I like Russia actually".

"Are you a communist?" I asked.

"No! No 'ist' for me. I am only interested in fellow human beings. No ist, no religion, no colour, no racism".

He looked at me when he said these last two things. I did not see a non-white person all day in Montenegro: he meant to let me know that my skin colour did not matter to him.

He continued, "No religion or race for me. The language of love of all human beings, that is the only one".

We had taken the few hundred steps to Slobodana Skerovica, the street I was looking for. We bid each other goodbye.

I understood - I think - what he was trying to say. He had a desire to be his own person, a man from his own society and his own culture. Yet he, like most others I encountered today, spoke such good English (just like, perhaps, his father or grandfather may have possessed a good working knowledge of Russian), and seemed like he would quickly learn his way around, or migrate to if practical necessities dictated, London or New York. How hard it is to stay away from global currents... --

Pod Volat is a wonderful restaurant. (Along with, in London, Dishoom's nostalgic evocations of vanishing Irani cafes in Bombay) It has the most lyrical introduction to an eating house that I have read. Ably translated from a no-doubt far more lyrical Montenegrin. Read, especially, the first two paragraphs.

I came here for both lunch and dinner that day. This restaurant in this city seemed to me achieving something that is vanishing in global capitalist cities like London. It was a place that all classes and types of people could afford and came to. Around me I saw a well-dressed family celebrating a child's birthday orders large bowls of food, and groups of football buddies, but also men in half-torn jackets of limited means nursing their 1 euro bottle of beer, sharing a cigarette with passing waiters and watching the football on the screen.

The goulash, cabbage rolls, bread and boiled potato reflected not just the prices but what seemed the simplicity of the place around me.

Ah, if only I spoke Montenegrin, then I would spend away an evening listening and talking to a man like this at a bar like this, nothing except a few Christmas bulbs on the walls, places full of men, cigarette smoke everywhere, drinking pear brandy and mugs of cool, light Niksic!

0 notes