Video game reviews, rants and commentaries from a hobbyist. Read more here: elitegamer.ie/author/ryangaffney/

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

-1- The Dream-Quest of Bloody Yharnam

-1- The Dream-Quest of Bloody Yharnam

Randolph Carter and the Mechanics of Lucid Dreaming “I wonder, though, if I have a right to claim authorship of things I dream? I hate to take credit, when I did not really think out the picture with my own conscious wits. Yet if I do not take credit, who’n Heaven will I give credit tuh? Coleridge claimed “Kubla Khan”, so I guess I’ll claim the thing an’ let it go at that. But believe muh, that…

View On WordPress

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

The first in what will be a long series delving into the occult symbolism and magick techniques to be found within Bloodborne. The set the groundwork though, I needed to begin by analyzing Lovecraft’s life and work to address the myths and misconceptions about where exaclty “the occult” can be found in HP’s work.

I think this part in particular might be interesting to non-gamer occultists. The rest, however, will be much more targeted towards non-occultist gamers. I will be walking you through lucid dreaming techniques, the symbolism of the moon, “headlessness” and the occulted body as we go.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

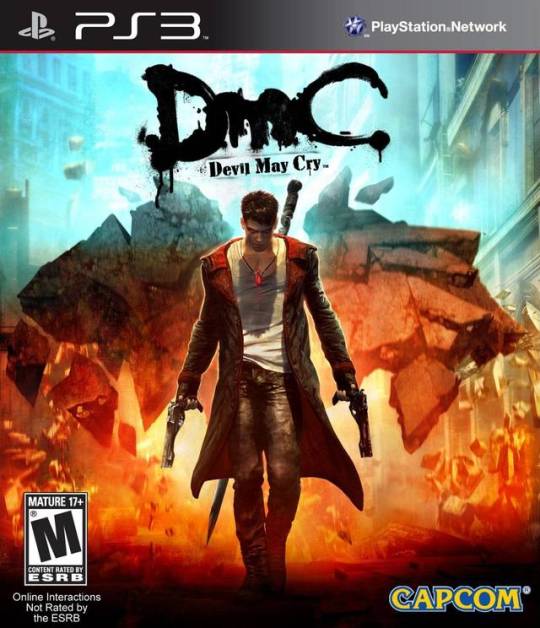

Devil May Cry: Series Retrospective- "DmC: Devil May Cry"

At long last, I sat down and played DmC: Devil May Cry. Well and truly, the dust has settled, the dead horse has been beaten into compost, and the reactionary rages and defenses have died down. And, for myself, I think my fanboy passion for the series has subsided.

A weak Special Edition, a pachinko machine and a bad MvC model later, I hold out no honest hope for the Devil May Cry franchise now. We’ll always have the Temen-ni-Gru Dante...but we’re not getting back together, lets face it.

So now, when I look at Ninja Theory’s protagonist, who I will still refer to as Donte, the fresh insult that he used to be is now replaced with a genuine, tryhard, grittiness that just seems cute in an “ah, bless” kind of way. He’s no longer the sour white whale that ate my favourite character and franchise, he’s just a little fish who flops around in a harmlessly funny way.

....before the massive flaws of the game come forth.

This review is based on the PS3 launch version and does its best to criticize it on its own merits/failings, not merely on fan insult or in comparison to the previous games. But it is after all called “Devil may Cry”, so its existence as part of a wider franchise isn’t ignored either.

Also, fair warning, this is going to be long as hell. Which is suitable, because it feels like hell sometimes...

Technical Qualities

The engine/optimization is dogshit.

Ninja Theory infamously rejected Capcom’s offer to translate their wunderengine, MT Framework, into English so that they could use it. Instead the team built DmC: Devil May Cry using Unreal Engine 3, which was already starting to look dated by 2010 when the game was announced. For perspective, Unreal Engine 4 was revealed to the public before DmC even came out. The likely reason Ninja Theory chose to stick with Unreal was because of a developer kit popular with young game creators. Unreal 3 was a ubiquitous engine in the last gen of consoles, being the backbone of games like Bioshock: Infinite and the Batman: Arkham series. But you’ll be hard pressed to find any games using it that were as fast paced as the Devil May Cry series.

Off the top of my head, games that use Unreal 3 usually have collision and texture pop-in problems. This is less of an issue in first person or isometric games when player movement and camera angles/viewable space are restrained, but it’s disastrous for something like DmC with its wide angle camera, large open areas, dense enemy count and fast player movement.

On the very first mission, in no more than 2 minutes of having control, Donte got stuck in a wall as I tried to go through the level like a normal player. This was followed by hideous amount of texture pop-in, audio glitches that muted parts of the soundscape, a couple of attacks that didn’t connect with enemies when they should have, and loading times out the arse.

A nasty little secret I only found out from replaying it first hand was that many of the mini-cutscenes (like when Donte looks at the Hunter demon hop around buildings, or does a backflip as he collects his guns) are secretly loading screens, unskippable until the loading operation is completed. All of which are frustrating to have to sit through in such a fast paced game. The way they make such a deal out of the same, generic enemy spawning in by giving it a dramatic close-up every time feels patronizing on repeat fights. “OOOH look! It’s a flying thing again!”. Yeah, no game, these things are easy to kill and I know you’re covering up something with this. Nice try.

Without seeing the development build firsthand, I can’t say for certain why it ran so badly. The release of the Definitive Edition for PS4/XBONE implies that it was a hardware limitation...but....like....that’s what optimization is for; making games run well on older hardware. More on this later, but design choices in level layouts, for instance, can remedy this. You can, for instance, segment levels in a way that stops you from seeing large areas at a single moment, reducing how much the consoles needs to render and thus cutting down load times.

Instead, what we largely got were huge foggy rooms and camera lens flares there to hide unloaded textures. The problem then is that it just, in my opinion at least, doesn’t look very good. Think of how Silent Hill 2 and 3 manage to still look so good due to how they segment rooms with doors you can’t see beyond. Or how the use of fog doesn’t cover up anything that you’re supposed to be looking at. And how they manage to have shorter loading times for it, a whole generation of consoles in the past.

Another trick is to “hard bake” lighting effects into the level’s textures themselves, rather than relying on extra shader operations. It’s more taxing on hardware to emulate, say, the actual light physics of a red spotlight instead of just making the textures of the walls and floor red, using trickery to make it seem like there’s a functioning red light there. Open world games generally don’t have this option, but with Devil May Cry, which is a linear series with rarely changing environments, you can use trickery like this effectively. Instead, DmC has more shaders -many of which look terrible in cutscenes- than it can handle.

Ninja Theory did a bad job of optimizing their game for their primary hardware. Even with the update there were visual problems, audio glitches and collision bugs throughout the entire game. It’s far from unplayable, but it’s ropey for a AAA game.

Level Design

Before I get into the artistic choices, I want to take a moment to look at the more technical, grounded aspects of how Ninja Theory designed levels.

Most of the previous Devil May Cry games are economic with their level design, reusing areas multiple times over with remixed enemy layouts and the occasional change in lighting, music and even textures. This cuts down on development time, saves disc space, and allows the designers to really put care into each individual location. Resident Evil, the Souls games, and Deus Ex: Human Revolution are other good examples.

DmC had potential for this with its “living city” concept. The best use of this concept is with Mission 2: Home Truths, where Donte visits his and Vurgil’s gigantic childhood home. As you backtrack into familiar hallways and foyers, the corruption of Mundus’ influence causes walls to crack open, pathways to change shape and different enemies to spawn. It’s a great (re)use of assets that trip up your expectations as a player the first time around. It also uses some Metroidvania style locked doors and obstacles which you need certain abilities/weapons to traverse. The unfortunate limitation of that is that you can literally fly through some levels and skip entire sections of the game upon a replay; Mission 3 requires you to unlock the Air Dash move in order to clear a gap that appears early on, but you’ll already have it on a replay, turning a 20~ minute level into a 3~ minute one.

Sequence breaking like this doesn’t happen in any huge way though, due to how each level is an entirely separate area of its own. Likewise, most of these ability/weapon barriers lead to optional bonus areas that are slightly off the beaten path.

Linear level design isn’t inherently bad, but in this case I think it was a huge missed opportunity. Not only is there a parallel real world vs Limbo premise that has Donte shift from a greyscale, mundane city into a colourful, chaotic image of itself, that Limbo dimension has the ability to change in real time. If the level designers allowed players to shift from dimension to dimension in-game, a la Soul Reaver, or if they had just played up the “living city” concept in a more interactive way, the city would have been much more interesting and, ironically, feel much more alive than it does. Instead we got a linear, albeit pretty, collection of corridors with very little off the beaten path. DmC incentivizes exploration by hiding collectables, but “exploration” ultimately means turning left where you should turn right to find a Lost Soul behind a bin.

One place where they ALMOST got it right is the first Slurm Virility factory level. After a cutscene showing a mixing room, Donte and Kat break from the tour, slowly jog down some empty, boring hallways in to an equally empty and boring warehouse. Dante can’t attack or jump in this section, and there is absolutely nothing to interact with. It’s an unfortunately uninteresting forced walking section, only one small step above being an unskippable cutscene. Kat then sprays her squirrel jizz magic circle on the ground, Donte enters the Limbo version of the level, the room expands and the crates become platforms, and the level really begins from there. For reasons I never understood, Donte then has to take a huge route up sets of boxes and across dozens of different rooms to circle back on the way he came in. On the way back, he backtracks down the Limbo version of the boring hallways of before, except now they’re slightly less boring, with a few enemies to fight and moving walls and floors. Then you get to the mixing room (which is only shown in a cutscene) for a brawl, before moving on.

The reason this didn’t work as well as it could have are twofold. 1: You only see the real world version of a tiny portion of the level, and 2: said portion is boring as fuck and you don’t interact with it in any meaningful way. But hey, at least the idea was there.

Moments where the living city concept is pushed to the side for more one-off but more effectively done ideas can be found in the upside-down prison, the short prelude to the Bob Barbas fight and Lilith’s rave.

The upside-down prison starts off fairly strong, tapping into one of those childhood ideas we all idly wondered about; what if gravity suddenly shifted? The level starts off strong and has moments throughout that give a trippy sense of vertigo. Mostly this is with car and train bridges, but unfortunately loses the point as it progresses. Because the prison isn’t just upside-down, but is also in Limbo, gravity is already unreliable and the bottomless pit below the floor already looks like the sky. Similarly with the lead up to the boss fight with Poison that has you run “down” a vertical pipe, it all looks floaty and weird by default, making further attempts to be floaty and weird just seem...normal. Likewise, the prison is mostly comprised of bland, urban and industrial textures, completely interchangeable with any old warehouse. You quickly forget that you’re upside-down at all.

The setting also well outstays it’s welcome, taking up 4 entire levels to itself with not enough ideas to justify it. There’s even one moment where, after meeting Fineas, you’re told you need to follow a flock of harpies to find their lair....even though their lair is a completely linear set of halls...That says it all really; there was a fun idea in here, but it was executed without the same creativity.

Following that is the tragically short Bob Barbas prelude. THIS is one of the single most interesting concepts in level design I have ever seen. Seriously. I cannot think of any other game that took news graphics and idents and turned them into platforming sections. Even moments during the fight where Donte is dropped into news chopper footage manage to do something brilliantly original, stylish and funny. But as quickly as it came, it’s gone before you know it. It’s a fucking crime that the previous 4 levels didn’t use the same concept to break up the monotony of their urban corridors. They could have had Donte teleport around chunks of the level using the various TV screens with Bob Barbas propaganda on them, hopping across idents until he got to the other side. Shame.

Next up, almost in a moment of clarity from the designers when they realized that could do digital environments and cheesy tv show graphics in their game more than once, we have Lilith’s nightclub. Again, much more interesting than the living city stuff, albeit a bit harsh on the eyes with its lighting effects. There’s not much to say about it beyond “it looks cool”, but it’s worth mentioning that it feels much more focused and fully utilized than the upside-down prison. All in all. the level design in DmC is at odds with itself, marked by its lost potential. The concepts are interesting, but the execution is almost always lackluster, favouring hand-holdy linear hallways with “cinematic” qualities over more interactive, open spaces with a sense of place. For a game that, pre-release, seemed to want to show us a more fleshed out world than previous games, it winds up as little more than a flat backdrop.

But oh well, DMC is all about the action happening center stage, right?

Combat

Combat in DmC is a mix bag.

The number of different attacks available and Donte’s versatility at chaining moves across 5 different weapons is pretty great. I’m a fan of how you can swap special pause combos across your alternate weapons; two quick hits with Rebellion, a pause, then a final triple smash with Arbiter takes a little extra skill to pull off but rewards you with a faster combo than if you just used Arbiter alone. Likewise, little tweaks like how fast Drive can charge now and how it does actual damage unlike Quick Drive in DMC4, or how you can hold Million Stab for longer, are all mostly fun changes. I tend to have a lot of fun with Osiris and find it to be the most versatile weapon for pulling off different combos. Its ability to charge up the more hits it delivers is a good incentive to hook in as many enemies as possible too, even if it means its uncharged state doesn’t do enough damage. Aquila is a fun supplementary weapon, mostly good for distracting one enemy with the circle attack and pulling the rest into range for Osiris. Eryx, however, is rubbish. Its incredibly short range, long charge times and weak damage output really throw it onto the trash pile when Arbiter is right beside it. Also, personal taste, but it just looks stupid. It’s like a slimy set of Hulk Hands. And they don’t even yell “HULK SMASH” when you attack. Previous DMC gauntlets all include a gap-closing dive attack to put you in enemy range, but the Demon Grapple doesn’t work the large enemies you’ll want to use it against. More on that in a bit.

Guns are mostly pointless. Donte can move laterally so much easier than before that long range combat is redundant. Charge shots with Ebony & Ivory are like Eryx in that they take too long to charge and don’t do enough damage to be worth the wait. Also, because you need to be in a neutral, non-demon non-angel, state to fire them, charging them up while you wail on someone only works if you limit yourself to Rebellion. Switching to Demon or Angel weapons resets the charge and limits you to a grapple move.

Which leads to another problem; 4 of your 5 weapons disable the use of guns. I mean, you’re not missing out on much by the end anyway because the guns are boring and ineffectual to use against all but one enemy (the Harpy), but it feels like a mistake. They literally give you guns in cutscenes as an afterthought. Like when Vurgil goes “oh yeah, have this, it’ll kill the next few enemies really quickly then sit in your back pocket for all eternity thereafter”. Donte never feels like he’s earning these guns like he earns the melee weapons, and they never seem to be worth a damn in gameplay.

The grapples are more useful but, again, having two different types feels redundant in combat. Large enemies can’t be pulled towards you, so why not do what DMC4 did and have one grapple that does both jobs; pull small enemies towards you, pull yourself towards larger enemies? The end result in either scenario is to get in melee range, so it shouldn’t make that much of a difference. Considering Aquila has a special attack to pull enemies in, why not offload those moves to the other weapons too? If you want to keep both pull-in and pull-towards moves in combat, why not give, say, Eryx a special pull-in attack so you can swap back to guns easier?

In short; while the combat is versatile and very satisfying to pull off combos with, large parts of it feel badly thought out. The moves and weapons that end up being useless most of the time have enemies spawn after you unlock them, just as an excuse to show how they work.

The infamous “demon attacks for red enemies, angel attacks for blue enemies” gimmick actually wasn’t as bad as I expected. Until I had to fight a Blood Rage and a Ghost Rage at the same fucking time. I don’t think I need to get into it due to how many other people have complained, but it was just fucking infuriating to say the least.

Okay, so.....Devil May Cry 3 did it better. Most people don’t seem to know this, but DMC3 gave you damage bonuses if you used the right weapon against the right enemies, signified by a subtle particle effect. Nowhere in the enemy or weapon descriptions does it explain this, but if you use your head (or just experiment) you can generally figure it out. Beowulf is a light weapon, Doppelganger is a shadow monster, using light on it does extra elemental damage signified by a flash effect with each hit. Cerberus is an ice weapon, Abysses are liquidy enemies, so using ice on it freezes them, signified by an icicle effect. etc But most importantly; it never STOPS you from using the “wrong” weapon against enemies. I don’t think I need to go into how annoying it is when your combat flow is interrupted by your angel weapon PINGing off a red enemy, but god damn it.

Credit where credit is due; Ninja Theory did emphasize the right part of DMC’s combat when they opted to focus on combos over balance. Both 3 and 4 had broken combos and attacks that skilled players could easily pull off, but they would make combat boring and the games all emphasized an honour system to prevent abuse. If you were good enough to use Pandora to break enemy shields in 4, you were good enough to not abuse it.

Then again, a games combat is only as good as its enemies.

Enemies/Bosses

So it’s a real shame then that enemies and bosses don’t push you hard enough.

The AI is atrocious. NO hack n’ slash should have two hardcore enemies accidentally kill each other without you noticing. The mixing room in the Slurm levels pits you against two Tyrants/the big fat dudes who charge at you. There’s an easy-to-avoid pitfall in the middle of this room. Once, on hard mode no less, they spawned in as usual and one accidentally nudged the other into the pit, insta-killing him while I literally stood still and watched...

Most regular man-sized enemies (Stygians, Death Knights, and their variations) have a common problem of just not attacking first, opting to side step around you forever until you run at them. Luckily there usually is one aggressive enemy mixed in there, like the flying guys with guns or the screamy-chainsaw men, so you’ll be forced to dodge into their range, but it’s embarrassing when they’re isolated. You’re left standing there, charging a finishing attack with Eryx like you have your dick in your hand, and these things are just strafing around you, doing nothing. So you miss with Eryx, step forward, and anti-climatically twat them about with Rebellion just to get it over with.

At first I thought this combat shyness was a design choice, but then it happened with the final boss, revealing it to be a pathfinding bug. But more on that later...

So yes, the red/blue enemy gimmick is bullshit and breaks the flow of a room-sweeping combo you have going, but it actually works really well with the Witch enemy who hangs back, projecting shields onto other enemies while she snipes at you from a distance. She’s annoying to hunt down when you’re dealing with 10 other enemies, so you have to prioritize whether you want to plough through them first or clumsily chase her down first. It’s a nice dynamic to fights, adding that extra layer of strategy to mix things up in a less punishing way.

The main difference with the Witch and the other colour coded enemies is that the Witch gives you options. Blood/Ghost Rages do not, and make fights involving them feel like complete chores. You’ll find the one tactic that works, then rely on it every time.

No, the most egregious enemies were the bosses.

All of them, every single one, was terrible. Not including the Dream Runner mini-bosses, there was a total of 6, less than any of the other DMCs, which makes how sloppily designed they were all the more horrendous. Every single boss is formulaic, partitioned out into “segments” cut up by mini cutscenes that have Donte do something sassy when he works them down enough. But each of those segments tend to have Donte repeat the same, boring, tired tactic until the fight is over. Bob Barbas is the worst example; jump over his beams, use that one Eryx attack to slam into the nonsensical floor buttons, wail on him for a third of his health bar, kill 10 minor enemies in his news world, repeat two more times.

No matter what difficulty you’re on, these bosses never manage to be a challenge due to how placid they are. They will always accommodate their little “formula” you need to solve to beat them.

It’s baffling, because the previously mentioned Dream Runner mini-bosses are great. They’re aggressive, reactive, open to almost any combo you can outwit them with, and don’t force you to repeat the same set of steps in every encounter.

Vurgil on the other hand....

So, here we are, the grand finale. The ultimate evil has revealed itself, and it’s your own brother! You’re clearly a badass because you just took down Satan himself along with his army, so surely the only thing left that could challenge you is your more experienced twin.

Well, he would, if his AI didn’t start the show by consistently suffering from that same pathfinding bug that makes minor enemies interminably strafe around you. So far so good for my first playthrough. So I attack him, maybe hit him 5 times before a min-cutscene rears its head because I’ve suddenly made it into the next stage. Same thing happens once or twice. Then, somehow, Vurgil’s model freezes in the air during one of his attacks. He hangs there indefinitely until I attack him again. Then, at the end of the fight where he’s summoned a clone (because he can do that apparently, not that he’s ever so much as referenced the fact) so his real self can take a knee and heal, I’m supposed to use Devil Trigger to move him out of the way and finish the job (though, I don’t understand why the real Vurgil isn’t also thrown into the air). I do so, but the clone lingers on the ground for a moment, trying to attack me before just zipping into the sky; another bug. I attack the real Vurgil, but nothing happens at first. I keep wailing on him, hoping that one of my attacks will eventually collide and then, -Scene Missing-, the final cutscene of the battle plays.

Do I need to say any more? Do you see what a fucking mess the boss fights are? The final battle for humanity, the emotional crux of the story, the update to the final unsurpassed boss fight of DMC3, reduced to a buggy, embarrassing slap fight that gave me four glitches on my first playthrough.

The whole thing bungled the climax of its story. But, then again, was the story really that sacred to begin with....

Concept and Story

I promise I will not use the word “edgy” here.

Satire and social commentary, no matter how cartoonish, is a weird fit in a Devil May Cry game. DMC2 had an evil businessman too, and 4 ended with you punching the Pope in the face, but neither seemed to say anything substantial against capitalism or religion. They existed in a much more fantastical place, where any sort of commentary was aimed at a more philosophical target. “What makes us human? What makes us into demons? What is hell like? Is family more important than what you feel is right?” The previous games are all centered around a much more personal, individualistic identity crisis, and not any sort of populist, society-wide problems.

DmC brings up surveillance states, the most recent economic crisis and late-capitalism, soft drink addiction/declining nutrition, news manipulation, the prison industrial complex, conspiracy culture, populous revolt, some scant mentions of mental institutions, hacktivism, and the Occupy Movement. These topics, all of which are pretty damn serious and warrant long discussions, are simply decoration for a story about fantasy demons secretly running the world They Live style. Hell, it basically IS They Live, only the aliens are demons and the tools of control are more contemporary. (somehow there’s nothing about the internet in there though...)

All in all, its treatment of modern issues is childishly simple at best and cynical at worst. Sure, the game presents itself as defying capitalism and social engineering via advertising, but it then goes on to launch an ad and hype campaign bigger than any of the previous games, spanning across billboards, phone apps, social media promotion, the usual games media rounds and expensive pre-rendered television commercials. Hell, they even had an ad for their ad! All of this amid a gigantic fan backlash and in-fighting with games journalists on whether people were mad about Donte’s hair colour of if they were just outrightly entitled.

The fact that lead designer and writer Tameem Antoniades responded to this backlash and feedback by tweeking Donte’s design and adding in a random moment were a wig literally drops out of the sky onto Donte’s head for a jab at this “controversy” says something about the intent he had with his story; There is no real political statement behind DmC, it simply pulls from what was in the news at the time, and uses it as fodder for an otherwise archetypal plot.

The problem is that it tries to do this while also talking about hellish demons, heavenly angels and earthly humans. Well, mostly demons, because the angels are absent from the plot and Donte doesn’t seem to have any sort of Angel Trigger, and the only named human character is Kat, who doesn’t have much ploy within the story; she’s there to be rescued, and provide minimal help with a pat on the back from Donte. So demons rule the world, the angels are absent, and the people who suffer are us lowly humans. But it’s a half-demon, half-angel who “saves” us all/reduces the city to rubble, while all us humans can do is post about it on Twitter. Doesn’t sound very empowering to me.

The main villain should say it all. He’s some sort of businessman/oligarch/banker/economist/military commander/mayor/Satan, but he makes the undeniable point that he gave human civilization it’s structure. He has a wife he at least somewhat cares about, and a child he has high hopes for. He (and his wife) shows more emotion than any of our protagonists, and they have more at stake than anyone else, with a genuine vision for the future no less. So, when he very reasonably asks Donte what his goal is, all Donte can say is “freedom” and “revenge”, then continue to childishly taunt him when pressed further. I could go on about how unhealthy the obsession with the post-apocalypse our generation has is, but suffice to say; Donte is not someone to look up to.

Donte himself, and by extent his story, has no real ideological motivation behind him despite being dressed up as an anarchist. His motivations and arch as a character are no less two dimensional than the original Dante, but now manage to be over-stated and hamfisted, with an added veneer of “politics”. Vurgil points how much he’s supposedly changed right before the final boss fight, but how he changes doesn’t include a strong statement of intent. What does Donte want? Fucked if I know! Fucked if he knows.

All of this says nothing about how...well....plain bad the writing is. The dialogue is famously cringeworthy and the plot has more holes than a sponge.

If Mundus was hunting Donte to kill him this whole time, why can’t he find him despite having multiple cameras aimed directly at this house? Why didn’t he just kill him when Donte was in the orphanage run by “demon scum”? Where was Vurgil this whole time? Why does Kat need to hit the Hunter with a molotov? Actually, what the fuck is she doing in the real world while this is happening? Are people just ignoring this pixie girl throwing bottles around a pier? What’s that weird dimension Donte goes into to unlock new powers? If it’s his own head, why are Mundus’ demons in it? And why would it change his weapons? Why doesn’t he have an Angel Trigger? If Vurgil can do all that cool shit he does in his boss fight at the end, including opening a fucking portal to another dimension, why does he need to rely on Kat to hop dimensions earlier on? Or rely on anyone for that matter? Why does he have white hair when he’s born, but Donte has black hair until the end? If Mundus is immortal, why does he need an heir? Why does time randomly slow down after Vurgil shoots Lilith? How did Kat know the layout of so many floors in Mundus’ tower? Surely he didn’t give her a tour of the whole building, right? Did Donte and Vurgil fuck the entire planet by releasing demons into earth and destroying world economics and governments? Or are there pre-existing governments anyway?

Seriously, I could go on forever.

Beyond basic plot, logic and diegetic continuity (the rules of DmC’s world, and how it suspends your disbelief), you get into more subjective questions like “is Donte a likable character?”

I, perhaps surprisingly, think he is. He’s such a tryhard asshole for the majority of his game, never stopping to think about what he’s doing or to engage with the They Live world he lives in that he is, honestly, a bit adorable. He’s not someone I’d ever have the patience to hang out with in real life, but he is at least consistent. He’s a total lughead and he almost blows up the planet, but it makes sense that a nihilistic, “act first, think later” bro would do that.

And I think that sums up his story too; dumber than it thinks, but entertaining all the same. It’s a different kind of dumb than the original games, a kind of dumb that stares at the camera wall-eyed instead of with a sideways wink.

Conclusion

As of writing, I consider Devil May Cry to be dead as a series. With no solid news from Capcom on further projects for 7 years now, DmC: Devil may Cry is the swansong of the entire franchise. Well, beyond shitty cameo costumes in Dead Rising 4, or pachinko machines or whatever.

Likewise, more recent hack n slash series like Bayonetta, Metal Gear Rising and Nier: Automata have risen to challenge Devil May Cry for its crown, and without something better than Ninja Theory’s efforts to stop them, they’ll probably get it.

DmC is not a complete trainwreck. It’s enjoyable, worth the second hand price and 10+ hours of your time. It’s entertaining in a similar way a bad film is; so long as you don’t expect too much from it, you’ll have a laugh. Let go of your bitterness with Ninja Theory and Tameem and you’ll poke fun at it in a less mean-spirited way then your fan rage wants you to. DMC deserved to end on a better note than this, but.....honestly....fuck it. Capcom probably couldn’t make anything much better themselves these days anyway.

Treat DmC like a pug; malformed and lumpy, probably should have been neutered a generation ago, but funny to look at and play with, even though it’s covered in its own slobber.

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

Looking at folk horror’s footprints in the video game world really shows why some of the most renowned games earned that reputation.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Dr. Kleiner from Half-Life is not the man you know. With real life ties to conspiracies, UFOs, psychic energy, bigfoot, vanished punk rockers, crazy cults and Lovecraftian entities, following his backstory is like riding a roller-coaster made of hypercubes. No, really, I’m not joking in the least. He led pedestrians into San Francisco water works, and I’m about to lead you into the most bizarre corners of reality you’ll see all month…

Had so much fun writing this one.

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

Tomba was one of the worst games I’ve ever played and I hate myself for not just quitting it and playing something else.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actors amaze me in general, but actors who can do it in a big green room with nothing but tennis balls to guide their eyeline baffle me. I remember when that image of Ian McKellen having a bit of a breakdown on the Hobbit came out and completely understanding how he felt. It was doubly sad because the original LotR trilogy was so beautiful and meticulous with it’s art design and holds up incredibly well for it. Meanwhile the Hobbit trilogy just looked like some sort of new unintentional Def Leppard video at it’s worst moments.

To take it back to the point I was making with the article and psychogeography; when CGI is used as a crutch in film, it robs the world of it’s weight. I’d actually talked to the creator of Reboot (who ended up working on Mad Max: Fury Road) about this in relation to Avengers: Age of Ultron and he made the point that it’s too obviously animated. They create these photo-realistic models and then have them move like Looney Toons, making this uncanny dissonance. It’s the same for camera movements; you get too much Bayhem/overcooked pans, zooms, tracks and swings to show off a something that really just isn’t that interesting. When it comes to showing scenery, it shows it to you in this totally ungrounded way were the camera is flying drunkenly around to really shove it in your face.

It ends up coming off as hollow, which is ironic because most of a physical set is literally hollow. It’s the lack of options and the crew working within limits that makes it feel heavier, I think. Take any action sequence from The Hobbit trilogy and pick three shots and you’ll see impossible, overdone camera movement with a complete disregard for physical space. You’ll have a camera floating through the air panning, diagonally, zooming and dutching for a shot that only lasts 3 seconds showing a dragon trash about. No matter how realistic the CGI model is, how it’s used and how it’s presented is what makes it feel fake.

What’s funny is that it is impossible to do this in games with free floating cameras because controlling something like that in real life takes maybe 3 people using both of their hands, while you have your right thumb. And, likewise, because game worlds tend to be consistent and don’t/can’t move their “sets” around for individual angles.

How fucked up is that? Video games feel more realistic than greenscreen films.

Play, Don’t Show: Geographic and Forensic Storytelling

“In my opinion place is probably the single most important element of any work of fiction; arguably even more important than the characters and the plot, as it is always place that both character and plot emerge from, and exist in the context of. This is true whether we’re talking about a real, existing location, or about a landscape that the author has invented.

While place is obviously massively important in successful horror fiction I would say that this was just as true of every other type of fiction. Certainly, an exhaustive investigation of a place that is very tiny when considered in three dimensions and immense and haunted when considered in four or more….

And while there are certainly considerable horrors and tragedies bound up in that place, I feel that unless we excavate the whole of a place, including its humour, its triumphs, its history and its politics then we run the risk of not understanding it in its entirety. Of course, the slant that we put on a place will vary depending on what we want an individual story to achieve, but I would advise that you find out absolutely everything that you can about a place, trusting that fascinating or reveal details will be uncovered, or previously unnoticed poetic linkages.

Yeah, place: where would we be without it?“

-Alan Moore

I sometimes work as an intern in film and television art departments. In short, the art department is responsible for the world of a film. Set design and props mostly. You’re given a script that might be set in, say, a certain character’s house. Beyond the necessary details needed for the action, the art department is left to interpret how to express the personality of the owner of that house with paint, furniture and decoration.

When I walked onto the set of season 2 of Ripper Street, which is set just after the infamous Whitechapel murders, I couldn’t believe how real it felt in person. I assumed that, being a television program were you only see a small window into a given world, it would feel fake once you saw it up close in three dimensions. Quite the contrary; unless you knocked on the fake brickwork and heard the hallow echo of fiberglass, it’s as real as it was in the 1800s.

What strikes everyone when they start in the art department is how wasteful it can be. I spent about 3 full days making fake litters for a post office set. Piles of it. All with hand-written addresses, fake recreations of authentic Victorian stamps, ink marks and registration seals, the odd bit of ware from handling, everything that would make it feel real at a glance.

And it ended up in the background of a 5 second shot, out of focus. Likewise, on another set for an episode based around a Crowley-inspired cult, the master painter made a gorgeous alchemical mural on one of the back walls only to partially hidden by a bed and drawers on the day.

So you naturally wonder what the point of doing all that work is for it to barely be in there at all?

Well, it’s for the first reason; it feels real when you’re standing in it. It offers options and inspiration for the director, cinematographer and actors once they’re in the scene, because they’ll likely come up with something on the day. You create a space that feels alive and makes sure they don’t need to suspend their disbelief too hard. You allow the cast and crew to immerse themselves in a place and indulge a fantasy well enough for them to work their own magic.

Still, as an audience watching it through a window, it’s hard to get that same sense.

But not with video games. Games can create a type of storytelling that no other mass medium can, driven by the curious cats who are compelled to wander, explore and examine.

Keep reading

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Play, Don’t Show: Geographic and Forensic Storytelling

“In my opinion place is probably the single most important element of any work of fiction; arguably even more important than the characters and the plot, as it is always place that both character and plot emerge from, and exist in the context of. This is true whether we’re talking about a real, existing location, or about a landscape that the author has invented.

While place is obviously massively important in successful horror fiction I would say that this was just as true of every other type of fiction. Certainly, an exhaustive investigation of a place that is very tiny when considered in three dimensions and immense and haunted when considered in four or more....

And while there are certainly considerable horrors and tragedies bound up in that place, I feel that unless we excavate the whole of a place, including its humour, its triumphs, its history and its politics then we run the risk of not understanding it in its entirety. Of course, the slant that we put on a place will vary depending on what we want an individual story to achieve, but I would advise that you find out absolutely everything that you can about a place, trusting that fascinating or reveal details will be uncovered, or previously unnoticed poetic linkages.

Yeah, place: where would we be without it?"

-Alan Moore

I sometimes work as an intern in film and television art departments. In short, the art department is responsible for the world of a film. Set design and props mostly. You’re given a script that might be set in, say, a certain character’s house. Beyond the necessary details needed for the action, the art department is left to interpret how to express the personality of the owner of that house with paint, furniture and decoration.

When I walked onto the set of season 2 of Ripper Street, which is set just after the infamous Whitechapel murders, I couldn’t believe how real it felt in person. I assumed that, being a television program were you only see a small window into a given world, it would feel fake once you saw it up close in three dimensions. Quite the contrary; unless you knocked on the fake brickwork and heard the hallow echo of fiberglass, it’s as real as it was in the 1800s.

What strikes everyone when they start in the art department is how wasteful it can be. I spent about 3 full days making fake letters for a post office set. Piles of them. All with hand-written addresses, fake recreations of authentic Victorian stamps, ink marks and registration seals, the odd bit of ware from handling, everything that would make it feel real at a glance.

And it ended up in the background of a 5 second shot, out of focus. Likewise, on another set for an episode based around a Crowley-inspired cult, the master painter made a gorgeous alchemical mural on one of the back walls only to be partially hidden by a bed and drawers on the day.

So you naturally wonder what the point of doing all that work is, for it to barely be in there at all?

Well, it’s for the first reason; it feels real when you’re standing in it. It offers options and inspiration for the director, cinematographer and actors once they’re in the scene, because they’ll likely come up with something on the day. You create a space that feels alive and makes sure they don’t need to suspend their disbelief too hard. You allow the cast and crew to immerse themselves in a place and indulge a fantasy well enough for them to work their own magic.

Still, as an audience, watching the tv show and viewing it through a window, it’s hard to get that same sense.

But not with video games. Games can create a type of storytelling that no other mass medium can, driven by the curious cats who are compelled to wander, explore and examine.

Replaying each start point of the Tomb Raider canons (1, Anniversary and TR2013), I was struck by how much more exciting the first two were when compared to the newest one. It made no sense on the surface; the new one was so much faster and spectacular than the originals and much less frustrating to control. Likewise, it had the cool folky Japanese setting that I love.

It was just too cinematic. Too linear, too visual and too hand-holdy. The original Tomb Raiders (1 to Angel of Darkness) and even the first reboot trilogy (Legend, Anniversary and Underworld) would sometimes literally drop you in an open space and say nothing. With nothing to shoot at, you naturally wander about, figure out what you can climb, maybe stumble across secrets, and find a path to the next area. While it was frustrating, boring and overly punishing to some, if you acclimatize to Tomb Raider by climbing around, you’re fully immersed.

The tension and awe I felt in the pit of my stomach was comparable to a good survival horror. Knowing that I could fall and lose hours of progress, or fearing that the next corner would reveal an enemy instead of a bonus item, created a sense of presence to each location. While older platformers like Mario, Rayman or Crash Bandicoot essentially give you the same goal of getting from A to B with various themed skins on top, you’re very clearly running an obstacle course.

With it’s low-fi graphics, childish story and complete disregard for even a little historical accuracy, Tomb Raider creates an impressionistic exploration simulator that makes you feel like you’re on a true adventure. It marks an era in 3D action games that primarily focused on creating virtual realities instead of interactive stories. It forces you to take in your surroundings and provides enough quiet for you to hear your own thoughts.

A high number of pixels or a high level of realism isn’t required to create that sense; last I checked (which is probably 4 years ago now), even Minecraft does it when you play it in survival mode. But there’s no denying that it helps a huge deal. The less tied level designers are to boxy layouts and the more detail they can render on, say, a statue, the more layers they can add to both the geography and the psychogeography of an area. The thrill of exploration is all the greater when there’s more to see.

The first Devil May Cry’s setting, Mallet Island, stands head and shoulders above the settings of the rest of the series. It’s rich. It has an entire history behind it with little bearing on the main plot, but adds so much more than you can understand at a glance. It’s a late-renaissance Spanish castle with a long and dark (and accurate!) history of black magic practice that replaced the island’s human inhabitants with ghosts and demons. Dante travels through that dark history to uncover it’s secrets and find a way into the underworld. As you go, you find more recent footsteps left by pirates, treasure hunters and adventurers drawn to the island, only to meet their doom. There’s something in the bowels of Mallet that reaches through the Circles of Hell, inviting Dante and the player to walk into it...

The very architecture of the island shows literal layers of history and classic romanticism hearkening back to Roman times, on top of the warp brought on by demonic influence. Very little of that story is told directly with words, and what is there (the odd diary, plaque or brief bit of dialogue) is scant. The rest is left to your imagination and deduction.

Most games with a strong element of exploration do something similar. The Souls series is a great example of landscapes that tell you a story, as are classic horrors like Silent Hill, the earlier Resident Evils, Siren and Fatal Frame. Mostly, it comes hand in hand with a sense of ancient history and inherent mystery, although briefer histories and even forward-looking settings can do the same thing. Sci-fi games like System Shock (and Bioshock) have the same narrative and interactive focus on place, even though Citadel Station (and Rapture) aren’t as old as, say, Yharnam city from Bloodborne.

These fixed locations, which we imagine are built on layers of soil, brick, mortar and iron, are much more than a stage or a set. They’re fully three-dimensional, populated by designs that hint at something larger that, if you allow it, cause your mind to wander the same way a geologist or archaeologist might when looking at an outwardly plain field.

And, unlike the older mediums, the perspective is your own. You are your own tour guide, and there is no schedule to follow. You may walk absent-mindedly past the front hall and miss that interesting mural on the wall, only to come back later with fresh eyes.

The strategic choice to place something in a fixed location for you to move around, under or over, and to even hide devils in the details for the sake of a narrative is something once only reserved for architects and set designers, and only experienced by visitors and cast + crew respectively. In the art department, these fixed details are called “set dressings” and you are “dressing the set” when you make those creative choices. In game design, you are creating an entire reality, down to the physics that hold it together.

Due to a lack of vocabulary for game criticism, I’m calling it “geographic storytelling”; a level designer’s thoughtful attempt to hint at a larger story or history using the physical layout and motif of a level. To create a real sense of space, rather than a simply serviceable or pretty backdrop.

So what of the objects within the map/level?

The ones that aren’t fixed, that you can pick up or interact with in ways that aren’t simply navigating or observing them? The things that, in film and theater, are called “props”?

Without reusing the previous references (though they all do this too, the Souls games being the best example), Half-Life 2 has some great examples of this. Behind an oil tank near a lonely house that was raided by the baddies near the end of Highway 17, you can find a mattress, some health supplies, a handgun and a corpse with a hole in it’s head. Evidently, the poor guy was hiding here just a bit away from the house, only to commit suicide when he realized how hopeless escape was. There is no cutscene, collectible note or audio log to tell you any of this. You simply deduce it from the evidence, like a crime scene investigator.

Gone Home is another example of this, showcasing it as it’s primary feature, slowly revealing a familial history through what objects you find and where you find them (while the house itself creates a misleading “haunted mansion” vibe). It’s something the newest Tomb Raider does half-right; allowing you to collect and examine relics as an archaeologist would, to learn more about the island’s history. Sadly, it’s always placing them at the end of an otherwise arbitrary obstacle course or in nonsensical places like rooftops or behind staircases. Perhaps one of the best recent example of a game that uses the placement of items, bodies and other assets to tell stories is The Last of Us, particularly in chapter 6 “The Suburbs”.

In a chilling moment were you find a number of child-sized skeletons covered in cloth, you begin backwards-engineering what happened and who these people were as you progress through their abandoned shelter in a sewer to an outside suburb where they lived prior. You collect notes written by the previous inhabitants, find areas where they stored their food and ammo, and generally follow a path they took when their previous homes were overrun by the infected. It may not be the most original story in a time when post-apocalyptic fiction is harder to kill than it’s own zombies, but the way it’s told is fresh and thus much more disturbing.

This sort of thing can be done with reused assets, like in Half-Life 2′s case, or uniquely created ones, like in The Last of Us’ case. They tell backwards-looking stories that can be easily missed by players just aiming to beat the game. The thought put in there by the level designers shows a type of craftsmanship and artistry that’s often wordless and understated, which takes guts for game designers to create.

It goes beyond bare bones contextualization of some action, vaguely explaining why a certain enemy spawns in a certain place, or why certain items are found there. It creates a sense of history and injects some character into a fake body, a generic sword or a box of ammo. It’s a modest, occult type of storytelling that can only be read by investigative players.

Placement of items and assets aside, flavour text and just sheer consistent art design can give you more a complicated or more direct story behind something you just picked up.

L.A Noire has an entire system built around this that’s central to it’s plot and to beating the game with a good grade (you go to crime scenes, collect evidence, and use that evidence during interrogations needed to solve the case). Even games were examining items isn’t core to the experience can use it to it’s advantage. Off the top of my head I can’t think of a specific example, but the Elder Scrolls and Fallout series do it constantly. You might kill a bandit, see that he has an item from a foreign culture and deduce that he stole it from some unfortunate traveler who crossed his path.

Or, in the case of the Souls series, entire records of societies are told through flavour text. In Demon’s Souls, there is an area called the Tower of Latria that was once a college for magicians who used souls in their craft. Now in disarray, driven to a decadent hell, bodies are strewn about. Some of these bodies seem to be assassins judging from the daggers they conceal. One of which is wearing a Gold Mask. Collecting it allows you to read this piece of text in the menu:

A gold mask inlaid with a delicate design.

Even among the masked society that seeks to harness the power of Souls, only those of a particularly high rank may wear it.

When/if you later meet a character named Mephistopheles wearing the same mask, you’ll already know her background and have a hint as to her motives when she requests you assassinate other characters. Or, you can just not read it, never meet her, and never have that story told to you.

Again, there’s no cutscene or linear, non-interactive plot dump to tell you any of this. Nor does anyone spell it out for you as to why you found it in the Tower of Latria in particular. But if you pick up the right items, think on why they are where they are, and read as many descriptions as you can, you can figure it out: This masked society aims to rid the world of people who know how to use the Soul Arts (a system of magic in the Demon’s Souls universe), and the old monk at the head of the Tower of Latria, a place that was once a school for teaching said Soul Arts, was particularly adept with them. At one point, one of the masked society (backed up by other assassins whose bodies and items you can also find) attempted to assassinate the old monk but failed, presumably being killed by him.

Naturally, I’m naming this technique “forensic storytelling”. While geographic storytelling pertains to the fixed parts of a map and is closer to architecture and set design, forensic storytelling has to do with items and other movable assets within that map and is closer to prop design. More often than not, games that use forensic storytelling allow you to examine your items after you pick them up, though their placement within the world can be enough to tell a tale alone.

If you’re an avid gamer, you’re probably thinking “well duh”, but it’s important to highlight these two techniques in a time were restrictively linear “cinematic” games are more and more common.

“Walking simulators” like Gone Home, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Journey, Dear Esther and Proteus seem like reactions to it. While “cinematic games” like Ryse, The Order 1886, and everything by David Cage are all flashy overloads of gaudy action or exposition, “walking simulators” go for slow, quiet, contemplative narratives. They run on exploration, and according to critics exemplify “environmental storytelling”.

But environmental storytelling lumps in the two different disciplines I outline above. An environment is both the geography or architecture of a place and what inhabits that place after all. In games one can exist without the other. A landscape with a story can be barren and unpopulated by people or items, such as in Shadow of the Colossus, or a nonsensical, uninteresting environment can be filled with items that tell you a story, such as in Devil May Cry 4.

Likewise, environmental storytelling does not need to be reserved to the slow, artsy games and can be just another tool for storytelling in something more action packed. Devil May Cry is synonymous with over the top action, Dark Souls is renowned for tense boss fights, and The Last of Us is praised for voice acting and drama, yet all three utilize both geographic and forensic storytelling in a quiet way to provide more than just background atmosphere.

Outside of video games, there is an emerging sub-genre called “folk horror” that extends from film and television to literature, painting and even music. While it’s hard to nail down exactly what constitutes a piece of folk horror, it often has a strong sense of place and history.

The Wicker Man (no, not that one) is the go-to example in film due to it’s rural, faerie-like setting of Summerisle and it’s revivalist pagan culture shaping a paradoxically sunny story of horror. It is most often associated with British works of the 70s, but as the name implies, any sort of horror with a folky twist no matter it’s country or decade falls under the category. To me, because folklore is tied to the landscape of it’s origin, psychogeography is key to creating a piece of folk horror.

Psychogeography is a practice that encourages spontaneous wandering (dérives, in Situationist terms) and symbolic observation in a place, particularly cities were it’s easy to automatically go from A to B with your head down. Understanding said symbols requires a knowledge of history and folklore (for instance, you might see some statues on top of an old building and need to know the Greek pantheon to recognize them, or the erratic shape of a windy street may only be that way due to it once being a donkey trail, etc). The characters and actors of a space, particularly an ancient space, are what shape it. The land is shaped by time and history. That time and history is given a face through folklore and symbols. It’s circular.

If you can make the time, I recommend exploring the psychgeography of your hometown. It creates a sense of adventure you might recognize from the types of games I’ve been talking about. And, if you’re a game designer, you may gain a new sense of appreciation for what level design can do.

Film, television, painting, music and literature cannot offer the same interactivity that games can. You are (usually) given a singular perspective and a linear story in either. In games, you can explore as you would in a real space (though maybe with vehicles or athletic prowess you don’t have in real life) and discover these details for yourself rather than having someone explicitly point the camera at them for you. Hell, simply controlling the camera and taking the time to aim it at a building, landscape or pile of items long enough for you to really take them in is something you can only do in games. When I find myself on film sets or in interesting locations, I do it in real life, and wish other people could make the time to take in the world around them.

Or you could just not.

You could easily walk past all of these things, finish the main mission, get to the end credits and turn the game off.

But that world and all that’s in it are still there, waiting to be discovered for people with eyes to see.

55 notes

·

View notes

Link

TL;DR: The Suffering is Clive Barker meets....The Wire???

No, seriously, it’s this bizarre game that looks like an edgy gorefest on the surface, and it is, but the entire plot and lore of the game is socially conscious and morally grey. Enemy designs are actually based around institutional racism, systematic poverty and the impotent rage that brings.

If the gore and shock horror doesn’t scare you, then the implications and viewpoints it presents will.

1 note

·

View note

Link

As a followup to the previous post, I tried to figure out why I loved Bloodborne so much when Dark Souls 2 didn’t do it for me at all.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bloodborne- Not the first Lovecraftian Souls game

That is not dead which can eternal lie. And with strange aeons even death may die.

Kitab al-Azif

I found myself in a pit, my clothes saturated in the fluids of festering corpses, and not the fluids I want. To say that it was a mass grave would be narrow-minded. This whole accursed land -no, this very reality- is a mass grave. Most of the beasts surrounding me do not know it, they lack the insight.

Unfortunately for me, despite all my knowledge and experience of the shapeless, uncaring face of the “gods” at work, the particular pile of bodies I find myself nestled amongst offers a moment of security from the immediate danger just outside. A coven of hags, dogs and gorilla-like brutes, and I can’t tell exactly where they are no matter how much the cackle and howl.

Normally under such situations, my survival instinct would remain obsolete, but I’m carrying precious Blood Echoes and I need to bring them back to the Dream for them to be of any use. Perhaps their function is the biggest mystery of all; one that insight alone cannot explain. They appear to be a tool of another “god”, if not an integral aspect of that “god” itself.

I digress. Time is short, I must make a move before they do. There are monsters worse than the ones beyond that door, and I must become worse still to stand up to them.

“Fear the old blood”, pah! Fear me; I do not die...

To sum up why I love Bloodborne in a sentence; it’s apocalyptic. Not post-apocalyptic. Genuinely, rapturously, apocalyptic.

The minacious towers and steeples of Yarnham feel like the crooked teeth of the Mouth of Hell and the processions of grave-robbers, undying and plague-ridden citizens are a Dance of Death. The chaos looks like a Hieronymous Bosch painting. Mechanically too, the more aggressive combat emphasizes acting fast before your chance to regain health or tear out an organ is gone. Bloodborne is feverish from it’s story, to it’s artsyle, to it’s gameplay.

It’s funny how seemingly at odds Bloodborne is with Dark Souls and Demon’s Souls, particularly Demon’s Souls with it’s much more melancholic atmosphere and slow combat. If D Souls was about perseverance, Bloodborne is about opportunism. If Demon’s Souls was about hope in the face of hopelessness, and Dark Souls was about thriving in the face of the dead, Bloodborne is about keeping sane in the face of madness. It’s knowing when to go for the visceral attack or health-restoring counter and then going for it right away.

Yet when you look back at the previous games you can see the obvious thematic similarities. It’s as hopeless as the rest of the series when it comes to story. At the end, you’re presented the same choice; put yourself/your world out of your/it’s misery, or prolong the inevitable.

Even specific examples, like how the Duke’s Library in Dark Souls or the Shrine of Storms in Demon’s Souls resemble locations in Bloodborne, speak to it being an expansion of a central theme of the series.

That motif of colossal trees in the mist jutting out of the primordial soup, beginning with the finale of Demon’s Souls beneath the Nexus, appearing at Ash Lake in Dark Souls, and surrounding the Hunter’s Dream in Bloodborne, is more central than it seems.

It’s also fundamentally Lovecraftian.

Each of these locations provides a sense of player insignificance, showing just how small you scale up against the foundation of these games. The Hunter’s Dream is mercifully more cosy than the Nexus, but the looming moon and the towering trees are always present. You are always small. Enemies are always bigger and meaner than you, and the final boss(es) represent a fruitless struggle, or a bittersweet ending before you start NG+.

Which is why when people say “Bloodborne gets Lovecraftian half-way through”, I feel like I’m listening to people who have never read Lovecraft.

His influence has been there since the beginning. Hell, the final “boss” of the first game is called “The Old One”, and The King In Yellow (who wasn’t invented by Lovecraft but was referenced in his tales) makes an appearance in both Demon’s and Dark Souls.

Lovecraft isn’t all about his big tentacled monsters, nor are those tentacled monsters simply “aliens”. They’re often akin to cosmic forces, from a literal higher dimension (hence why their forms break the laws of evolution and physics, and why they so often drive people mad) and represent the unfathomable. The human mind struggles to comprehend them, and Lovecraft’s protagonists usually go through an existential crisis as their world shatters beneath their feet, revealing the abyss they’ve been walking on the edge of the entire time.

Azathoth, the most primal and base of the creatures/forces Lovecraft invented, is described thus:

[O]utside the ordered universe [is] that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity—the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes.

Which to me sounds like cosmic Death itself. Much like the Old One or the extinguishing fire of Lordran.

It’s the kind of inconceivably huge power that we mere mortals have no hope of overcoming, and so all we can do is pray that it leaves us be for just a while longer. And, perhaps, come to terms with it before it’s too late.

The pop-culture friendly side of Lovecraft’s writings (C’thulhu, maaaAAAaaadness, gothic stylings, the Miskatonic, and general spooky sci-fi weirdness) are present in Bloodborne in a much more immediate sense, with designs and names straight from the books populating most of the map. Even the more superficially gothic tropes from Poe, Stoker, Stevenson and Shelly that make up the common enemy types pop up in Lovecraft’s earlier stories. Bloodborne is more evocative of the image of Lovecraft’s works than the rest, and that’s what players and critics are reacting to, even though his themes have always been there.

It comes back to it being an apocalyptic, rather than post-apocalyptic, game.

The Lovecraftian cosmic horror theme felt like it had already settled in Demon’s and Dark Souls, that the world had already ended and you’re just left to slowly realize how you’re already doomed. The world was already torn to pieces.

In Bloodborne, you see the world being torn to pieces before your eyes as the night of the hunt moves along. There’s a sense of urgency; a ritual you have to stop, and a bunch of loud, screaming monsters to actively hunt down and butcher. Rather than the numb, grey Purgatory of Demon’s Souls that feels like Ireland or Glasgow on a drizzly winter’s day, you’re in a violent, volcanic mess where the quiet moments are the ones that scare you most in Bloodborne.

Underneath it all, where the trees loom large and the bottom cannot be seen, the true horror is waiting to be realized in every game.

What makes Bloodborne stand out from the other two, for me, is how violent and visceral it is. Literally visceral, not in a buzzword sense. Look at the above image. There’s viscera in it. Hanging from that horrible bastard’s back.

Once you get used to it, and your mind can filter out all the noise and tension long enough to think, you gain insight into how hopeless it all is. You and all of Yarnham (if not the entire world) have been doomed from the start and the best you can hope for is for it all to end up like Demon’s Souls did.

As per usual, the lead designer Hidetaka Miyazaki and his team delivered it all in a staggeringly layered, engaging and player-driven way were the meat of the story, should you choose to digest it, takes place in your head. A head that will hopefully withstand the onslaught of madness that existential realization brings on...

Reflecting on how the Lovecraftian horror has been expressed in the previous games reminds me of why I love them so much.

Demon’s Souls has a depressing ending that drained me of emotion and played with my head in a way no other game had prior to that. In the long silent sections where I was farming enough souls from the undying to get strong enough to beat the next boss, I started to wonder what exactly a “demon” was. Eventually one of the characters, I forget who, tells you without ceremony that they’re simply masses of souls. When I saw Maiden Astraea for the first time, it really hit me like a tonne of bricks that there’s nothing evil about demons and that the Monumental had been lying.

Then I began to wonder what the Old One actually was and what good putting it to sleep would even do. Turns out it was more like a portal to the afterlife, like the Norse Yggdrasil, and that it wanted to collect all of the souls that would have passed through it if not for the resurgence of the Soul Arts (people using souls for magic). Once I fully understood that, the choice to make at the end was a much more difficult one, but both ultimately resulted in death.

Which had me wondering; what is it that makes Blood Echoes so important, and what does it have to do with Formless Oedon? Why can I only spend it with the Messengers, and what are they “Echoes” of? What is the Hunter’s Dream and why do I, or Gehrman, never die?

To me, the implication is one that’s suitably bleak and horrifying for both a Lovecraft story and a Souls game. Think on it for a while and it captures that sense of cosmic horror without the spooky tentacles or hokey madness. All of the details of who founded what organization when, or whether there’s any true end to the hunt seem secondary next to what everyone is searching for, be that the “Truth” or the blood.

THAT’S Lovecraftian horror and it’s been in there, behind the beasts and beneath the blood, long before Souls became Bloodborne...

40 notes

·

View notes

Link

The final of my Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain articles. This time I’m looking at the state of the end of the game, how it got like that, and the situation we’re all left in at the moment.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

A snippet of what I made of MGSV’s plot and themes. This barely scratches the surface and, like the rest, will take some time for us to fully digest.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Gameplay review up! Part 1 of 3. The next article, the one I really want to write, is a breakdown of the story. But if you want to know if the game is worth getting or not, this one is for you.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

My first impressions article from earlier in the week. A full, loooong review will be coming once I play the game to death, because I feel like long games deserve that much.

1 note

·

View note