Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“...A lone woman could, if she spun in almost every spare minute of her day, on her own keep a small family clothed in minimum comfort (and we know they did that). Adding a second spinner – even if they were less efficient (like a young girl just learning the craft or an older woman who has lost some dexterity in her hands) could push the household further into the ‘comfort’ margin, and we have to imagine that most of that added textile production would be consumed by the family (because people like having nice clothes!).

At the same time, that rate of production is high enough that a household which found itself bereft of (male) farmers (for instance due to a draft or military mortality) might well be able to patch the temporary hole in the family finances by dropping its textile consumption down to that minimum and selling or trading away the excess, for which there seems to have always been demand. ...Consequently, the line between women spinning for their own household and women spinning for the market often must have been merely a function of the financial situation of the family and the balance of clothing requirements to spinners in the household unit (much the same way agricultural surplus functioned).

Moreover, spinning absolutely dominates production time (again, around 85% of all of the labor-time, a ratio that the spinning wheel and the horizontal loom together don’t really change). This is actually quite handy, in a way, as we’ll see, because spinning (at least with a distaff) could be a mobile activity; a spinner could carry their spindle and distaff with them and set up almost anywhere, making use of small scraps of time here or there.

On the flip side, the labor demands here are high enough prior to the advent of better spinning and weaving technology in the Late Middle Ages (read: the spinning wheel, which is the truly revolutionary labor-saving device here) that most women would be spinning functionally all of the time, a constant background activity begun and carried out whenever they weren’t required to be actively moving around in order to fulfill a very real subsistence need for clothing in climates that humans are not particularly well adapted to naturally. The work of the spinner was every bit as important for maintaining the household as the work of the farmer and frankly students of history ought to see the two jobs as necessary and equal mirrors of each other.

At the same time, just as all farmers were not free, so all spinners were not free. It is abundantly clear that among the many tasks assigned to enslaved women within ancient households. Xenophon lists training the enslaved women of the household in wool-working as one of the duties of a good wife (Xen. Oik. 7.41). ...Columella also emphasizes that the vilica ought to be continually rotating between the spinners, weavers, cooks, cowsheds, pens and sickrooms, making use of the mobility that the distaff offered while her enslaved husband was out in the fields supervising the agricultural labor (of course, as with the bit of Xenophon above, the same sort of behavior would have been expected of the free wife as mistress of her own household).

...Consequently spinning and weaving were tasks that might be shared between both relatively elite women and far poorer and even enslaved women, though we should be sure not to take this too far. Doubtless it was a rather more pleasant experience to be the wealthy woman supervising enslaved or hired hands working wool in a large household than it was to be one of those enslaved women, or the wife of a very poor farmer desperately spinning to keep the farm afloat and the family fed. The poor woman spinner – who spins because she lacks a male wage-earner to support her – is a fixture of late medieval and early modern European society and (as J.S. Lee’s wage data makes clear; spinners were not paid well) must have also had quite a rough time of things.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of household textile production in the shaping of pre-modern gender roles. It infiltrates our language even today; a matrilineal line in a family is sometimes called a ‘distaff line,’ the female half of a male-female gendered pair is sometimes the ‘distaff counterpart’ for the same reason. Women who do not marry are sometimes still called ‘spinsters’ on the assumption that an unmarried woman would have to support herself by spinning and selling yarn (I’m not endorsing these usages, merely noting they exist).

E.W. Barber (Women’s Work, 29-41) suggests that this division of labor, which holds across a wide variety of societies was a product of the demands of the one necessarily gendered task in pre-modern societies: child-rearing. Barber notes that tasks compatible with the demands of keeping track of small children are those which do not require total attention (at least when full proficiency is reached; spinning is not exactly an easy task, but a skilled spinner can very easily spin while watching someone else and talking to a third person), can easily be interrupted, is not dangerous, can be easily moved, but do not require travel far from home; as Barber is quick to note, producing textiles (and spinning in particular) fill all of these requirements perfectly and that “the only other occupation that fits the criteria even half so well is that of preparing the daily food” which of course was also a female-gendered activity in most ancient societies. Barber thus essentially argues that it was the close coincidence of the demands of textile-production and child-rearing which led to the dominant paradigm where this work was ‘women’s work’ as per her title.

(There is some irony that while the men of patriarchal societies of antiquity – which is to say effectively all of the societies of antiquity – tended to see the gendered division of labor as a consequence of male superiority, it is in fact male incapability, particularly the male inability to nurse an infant, which structured the gendered division of labor in pre-modern societies, until the steady march of technology rendered the division itself obsolete. Also, and Barber points this out, citing Judith Brown, we should see this is a question about ability rather than reliance, just as some men did spin, weave and sew (again, often in a commercial capacity), so too did some women farm, gather or hunt. It is only the very rare and quite stupid person who will starve or freeze merely to adhere to gender roles and even then gender roles were often much more plastic in practice than stereotypes make them seem.)

Spinning became a central motif in many societies for ideal womanhood. Of course one foot of the fundament of Greek literature stands on the Odyssey, where Penelope’s defining act of arete is the clever weaving and unweaving of a burial shroud to deceive the suitors, but examples do not stop there. Lucretia, one of the key figures in the Roman legends concerning the foundation of the Republic, is marked out as outstanding among women because, when a group of aristocrats sneak home to try to settle a bet over who has the best wife, she is patiently spinning late into the night (with the enslaved women of her house working around her; often they get translated as ‘maids’ in a bit of bowdlerization. Any time you see ‘maids’ in the translation of a Greek or Roman text referring to household workers, it is usually quite safe to assume they are enslaved women) while the other women are out drinking (Liv. 1.57). This display of virtue causes the prince Sextus Tarquinius to form designs on Lucretia (which, being virtuous, she refuses), setting in motion the chain of crime and vengeance which will overthrow Rome’s monarchy. The purpose of Lucretia’s wool-working in the story is to establish her supreme virtue as the perfect aristocratic wife.

...For myself, I find that students can fairly readily understand the centrality of farming in everyday life in the pre-modern world, but are slower to grasp spinning and weaving (often tacitly assuming that women were effectively idle, or generically ‘homemaking’ in ways that precluded production). And students cannot be faulted for this – they generally aren’t confronted with this reality in classes or in popular culture. ...Even more than farming or blacksmithing, this is an economic and household activity that is rendered invisible in the popular imagination of the past, even as (as you can see from the artwork in this post) it was a dominant visual motif for representing the work of women for centuries.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part III: Spin Me Right Round…”

9K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Traces of coca and nicotine found in Egyptian mummies - WTF fun facts

346K notes

·

View notes

Text

The European Roma institute for arts and culture just released a 253 pages book on the romani resistance during World War II, written by a collective of European historians

It is available for free here

19K notes

·

View notes

Photo

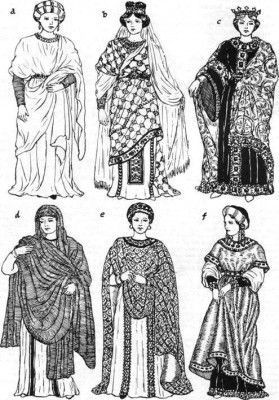

ℱavorite ℸropes → lady and knight

The Bright Lady is a woman of rank, often a Queen, Princess, other nobility or of otherwise high rank. Occasionally she will be a maiden of low rank, having significant beauty, kindness and grace whom the Knight has found admirable and worthy of his service. The White Knight has pledged his service to the lady and acts as The Champion to her. He has sworn his service to her above all else, not the country or some other greater organization, but dedicating himself solely to her protection and the furthering of her goals. Like her bright counterpart, the Dark Lady is a woman of high status. She may have inherited her position, but just as likely she has accumulated power with cunning, and even dark magic, and clawed her way to significance through the use of that power. The Black Knight often starts out as a White Knight, but under a Dark Lady’s influence, that doesn’t last long. So devoted to his Lady is he that he will sacrifice anything, including his honor, pride and values, to serve her as she sees fit.

118 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mythology family ♥︎ rhiannon for @darkvlings

the name rhiannon, literally means ‘great queen’. she played a number of roles familiar to celtic mythology: the otherworld mistress, the calumniated wife and finally the sovereign queen. earlier prototypes of this rhiannon, whose mythology is expounded in first and third branches of the mabinogi, can be found in the pagan goddesses matrona, the ‘great mother’, and epona, the gaulish horse goddess found throughout europe, as far apart as rome and hadrien’s wall. The myth of rhiannon represents the transitional point from the pagan rituals of the horse goddess cult, into its sublimated form: the chivalric mysteries of courtly love.

want to join?

496 notes

·

View notes

Text

“… there is a great deal of evidence which suggests that the idea of love – of being in love with the Queen – was of central political importance to the later Elizabethan court. All the leading members of the court participated in the game; it was not just the more glamorous courtiers that made lover-like approaches to Elizabeth. Sir Robert Cecil, generally portrayed as rather an unromantic figure, wrote to the Queen addressing her as God’s ‘celestiall Creature, who pleasethe out of Angellyke grace, to pardone and allowe my carefull and zealous desires’, declaring that ‘I am most blessed that I am a vassall to His celestiall creature’. He wore a miniature portrait of Elizabeth, a sign of admiration that was reciprocated in 1602 when Elizabeth ‘skittishly sized’ a miniature of Cecil from his niece, Lady Derby, and ‘pinned it at first to her shoe and later to her elbow-sleeve’. In his turn, Cecil responded by composing a poem set to music, emphasizing his devotion to ‘that Angelicke Queen’, who ‘at her elbowe wore it, to signify that hee/ To serve her at her elbowe, doth ever love to bee’.

We should not be too quick to write off such public statements as simply convenient fictions that allowed members of the court to pacify the Queen while getting on with business. It is clear from Cecil’s behaviour and from the other examples that will be discussed in this chapter, that the public flirtations between Elizabeth and her courtiers should not be understood to involve ‘love’ in the sense that the term is now understood. Hammer’s account of Elizabeth’s courtly flirtations casts them as almost genuine games of courtship and thus makes much of the fact that ‘each passing year made it more obvious that none of these suitors could ever consummate their quest by actually marrying Elizabeth’. But this is surely not what the ‘quest’ was about. The ‘courting’ of the Queen did not necessarily imply sexual, romantic or matrimonial intent, but was, rather, an important way of addressing the Queen. It also overcame many of the difficulties inherent in a system where an ageing female monarch presided over a court packed with ambitious younger men.

For Robert Cecil and the other members of the court who adopted this form of language as a way of communicating with the Queen, the fictions and assumed poses of courtly love were invested with political reality. This was partly because of the identities of participants and partly because the values that were expressed in the language of courtly love – loyalty, devotion, service, reward – were the values that underlay both the social and the political life of the court, embedded in chivalric culture. In particular, these values informed and shaped the key relationships between a monarch and his or her subjects and between those that competed for royal favour.”

Janet Dickinson, Court Politics and the Earl of Essex, 1589–1601

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

kind of want to make a video essay about how every fascist/totalitarian state trying desperately to copy the iconography and power of rome get it all horribly wrong because of their conservative policies. the reason rome was so successful was literally because it was new and innovative, with guaranteed rights for all citizens and a commitment to multiculturalism. their conquests lasted because they welcomed new demographics and allowed them to largely self-govern while still granting them fairly equal standing and encouraging them to mix their own culture, religions, and bloodlines with other romans. rulers were only allowed to stay so long as they bent to the will of the people – even Caesar, who literally every dictator has tried to ape to some extent, was eventually assassinated for being too power-hungry.

rome’s longevity was due largely to the fact that citizens had a voice, and most could live the way they wanted, self-govern after conquest, and be treated fairly equally. plus they actually maintained important internal structures such as infrastructure and public spaces/goods instead of focusing solely on military strength.

compare rome to fascist italy, which desperately tried to compare themselves to rome when, by looking to the past instead of the future, to ancestry instead of ability, they were suffocating themselves in the cradle and guaranteeing that they would NEVER succeed the way that rome did.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

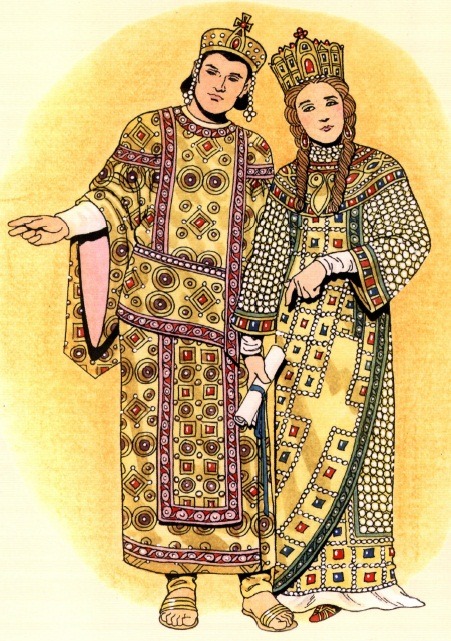

Byzantine royal fashions

First emperor Constantine the Great (272-337 CE) and his mother Elena

Both in dalmatic tunics; empress on the right

Emperor Justinian the Great (483-565) and his wife Theodora (500-548 CE)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t think a lot of people really understand that ecosystems in North America were purposefully maintained and altered by Native people.

Like, we used to purposefully set fires in order to clear underbrush in forests, and to inhibit the growth of trees on the prairies. This land hasn’t existed in some primeval state for thousands of years. What Europeans saw when they came here was the result of -work-

101K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greek fire is a term that anybody who has an interest in medieval history is aware of. First used in 678 CE, it routed an entire Arab fleet, delivered only by a tiny Eastern Roman Empire flotilla. Its existence is commonly credited as the reason the empire lasted so long, and they used it to win battles for over seven centuries. The perfect ancient weapon, one so infamous that the most common response to it was to flee or, if that was impossible, pray. However, its destructive powers are not the only reason why it is so infamous to this day. Its recipe was such a closely guarded secret that it was never written down – and so it was lost to time and memory.

What was in it? Historians can only theorize. Even people who managed to capture samples, as rarely as that happened, were unable to fully recreate it. All we can rely on are historical records in which fear and speculation are rampant. Was it truly as effective and fearsome as ancient people believed it to be?

In order to get a better idea of what exactly was necessary for “liquid flames” that could not be put out by water, I talked to our resident Chemistry teacher, Ms. Parameswaran. She told me that three things are necessary for a combustion reaction (fire): a fuel source, typically a hydrocarbon; oxygen; and something to ignite it, like heat or a spark. Flames cannot burn when the fuel is separated from oxygen, something commonly accomplished by submerging it in water or smothering it.

However, neither of those things, according to record, could stop Greek fire. The only things that could extinguish it were vinegar, sand, and oddly enough, urine. It actually burnt hotter when it came into contact with water, to the point that some sources claim that water actually ignited it. Ms. Parameswaran and I theorized that it might not have been just a combustion reaction, but an exothermic reaction, as well. Exothermic reactions create heat without flames, and there are plenty of things that react when they come into contact with water. Quicklime is often thought to be a key ingredient of Greek fire, and I agree with those assessments for one crucial reason: quicklime becomes very hot when it touches water. A person submerged in the ocean would certainly get chemical burns from quicklime, even if they were not truly on fire. This may be why people believed that the flames could burn underwater – how else would the sailors burn, if not from fire?

After this, I figured that I had to go more in-depth. I visited the Southeast Library, where the librarian at the information desk told me how to access a bunch of online databases full of ebooks, articles, and other sources, all of which had been vetted. She recommended a couple of different databases, some for simple research, and some specifically meant to help researchers craft an argument by providing opposing viewpoints on the topics they offer information on.

I found that a few other commonly agreed-upon ingredients were naphtha (a form of petroleum), sulphur, and resin. Naphtha and sulphur would easily form the flames once ignited, and sulphur fires move extremely quickly, which was another property of Greek fire. Another interesting effect sulphur fire has is that it produces sulphur dioxide, a gas that produces sulphuric acid when it comes into contact with water – including the moisture in your lungs. Even after submerging themselves in the sea, enemy sailors would still be burning, inside and out. The resin was likely used to thicken the mixture and make it sticky – thus why Greek fire stuck to everything it touched; and once it touched something, almost nothing would be able to put it out. Additionally, if you’re familiar with outdoor survival tips, you’ll also know that pine resin is known as “nature’s fire starter.” It catches and spreads very quickly, which is one of the reasons why forest fires happen so easily and are so important to prevent.

After researching its possible components, it is very easy to see why Greek fire is sometimes called “the first modern chemical weapon.” In later years, the Eastern Romans managed to put it into grenades and even flamethrowers. Both modern weapons, as well as napalm, were inspired by their technology and ingenuity. Greek fire was a shaping factor in the history of the world – had Constantinople fallen to the Arabs in the 600s, they could have conquered most or all of Western Europe, which had few governments strong enough or armies large enough to combat them. History could have looked very different, were it not for a Syrian refugee and architect named Kallinikos, who created the ancient world’s equivalent of the atomic bomb. His invention is the reason why the world is the way it is today. I’ll let you decide whether or not that’s a good thing.

Bibliography

Alchin, Linda. “Greek Fire.” Medieval Life and Times, www.medieval-life-and-times.info/medieval-weapons/greek-fire.htm.

All That Is Interesting on December 12, 2017. “Greek Fire: One of History’s Best-Kept Military Secrets.” All That Is Interesting, 12 Dec. 2017, all-that-is-interesting.com/greek-fire.

All That Is Interesting on December 12, 2017. “Greek Fire: One of History’s Best-Kept Military Secrets.” All That Is Interesting, 12 Dec. 2017, all-that-is-interesting.com/greek-fire.

Cartwright, Mark. “Greek Fire.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 14 Nov. 2017, www.ancient.eu/Greek_Fire/.

Gilbert, Steven. “Greek Fire.” Toxipedia, Atlassian Confluence and Zen Foundation, 30 May 2014, www.toxipedia.org/display/toxipedia/Greek Fire.

Knight, Judson, and Judy Galens. Middle Ages Reference Library. Vol. 1, Gale, 2001. Gale Virtual Reference Library, go.galegroup.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=T003&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=7&docId=GALE%7CCX3426200014&docType=Topic overview&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=&prodId=GVRL&contentSet=GALE%7CCX3426200014&searchId=R1&userGroupName=dclib_main&inPS=true.

Network, Warfare History, et al. “Greek Fire: The Byzantine Empire’s Secret Weapon the Ancient World Feared.” The National Interest, The Center for the National Interest, 2 June 2017, nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/greek-fire-the-byzantine-empires-secret-weapon-the-ancient-20955.

Potenza, Alessandra. “This blue sulfur hellfire in Wyoming is mesmerizing - and toxic.” The Verge, Vox Media, 10 July 2017, www.theverge.com/2017/7/10/15947592/sulfur-mound-fire-video-worland-wyoming.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bring Justice to Criminal Justice

Almost everyone can agree that the concept of law enforcement is a good one. The idea of people out there working tirelessly to punish evildoers and keep citizens safe is reassuring. It is a narrative that is upheld by the part of the population that rarely has to worry about getting targeted and victimized: white, wealthy, straight, cisgender people. The narrative varies amongst other white people, depending on how well they fit into all those categories, but as a whole, they are taught to consider police to be heroic and the justice system to be almost infallible – and for many of them, that may be the case. It is not so for the rest of the population. The American criminal justice system is deeply flawed, and does as much (or more) harm as good.

One of the most visible faults of the criminal justice system as a whole is police brutality. Police officers can literally get away with murder, provided that their victim is a person of color. Even if they are caught on camera, courts will often fail to indict. This is because police are well-known to be reluctant to testify against or prosecute their own, and judges, jurors, and prosecutors have more faith in their testimonies due to their profession. Many witnesses are also unlikely to testify if they are facing criminal charges, as it will hurt their chances in their own legal battles. Police involved in killings are indicted less than 1% of the time. Comparatively, civilians are indicted at a rate of 90%. From 2005 to 2014, thousands of officers shot and killed people, but only 48 were ever charged with manslaughter in that same time frame. How is this at all just? They rarely face disciplinary action from their superiors, often getting paid leave until any media attention dies down. Imagine if your sister or father’s murderer got a paid vacation for his trouble! 99% of these cases in 2015 have not resulted in an officer’s conviction. But cases without media or court attention are far more insidious – and far more prevalent. 52% of police officers report that it is not unusual for law enforcement officials to ignore the improper conduct of others, 61% say that they do not always report serious abuse that has been observed by other officers, and 84% of police officers stated in a survey that they have witnessed another officer using more force than necessary. These numbers are appalling. If this many have openly admitted to this, imagine how many did not. Statistically speaking, it is unlikely that every single instance of unnecessary violence perpetrated by police was an honest mistake made with good intentions, given the sheer number and scope of these instances, many of them victimizing the elderly and children. For an example, look no further than recent events in St. Louis, where riot police knocked over an old woman and walked over her, pepper spraying the people trying desperately to get to her and help her back up. There is no way they could feasibly have thought that assaulting that elderly woman was the best way to protect and serve. Even if that situation could be misconstrued as an innocent mistake, their attitude toward their stations and actions was made clear when they appropriated the “Whose streets? Our streets!” chant. The chant was originally used by people protesting for immigrant, LGBT, and black people’s rights – often for the right to simply exist in a public space without being in danger of violence or death. When St. Louis police took that chant, when they themselves are not oppressed or victimized, and are often perpetrators of these injustices, they sent a clear message: they owned the city, and the protesters could not have the rights and freedoms for which they were marching. It goes without saying that their behavior is both terrifying and disgusting.

However, physical violence is not the only way police harm the vulnerable – sexual assault is the second most common form of police misconduct. There are a few reasons that it is not as widely discussed, such as the stigma of discussing sex crimes, fear or shame preventing a victim from coming forward, fear that it will happen again, or fear of retaliation by their victimizer. Police predators will also target the most vulnerable demographics, with most victims being girls of color. According to research by Dr. Phil Stinson, victims are also “disproportionately underage,” meaning that the majority of victims are legally children. Police are meant to protect these people, but instead they use their positions to prey upon vulnerable women and kids. This is not the only way that they exploit the vulnerable, as a year long investigation by the Associated Press found “about 1,000 officers who lost their badges in a six-year period for rape, sodomy and other sexual assault; sex crimes that included possession of child pornography; or sexual misconduct such as propositioning citizens or having consensual but prohibited on-duty intercourse.” If police are willing to let their fellow officers’ misconduct slide, as shown above in regards to police brutality, who knows how many more have done any number of these things and gotten away with it? Clearly, they should not just take their badges. These people are criminals, not protectors, and they deserve to be in prison.

Despite all evidence to the contrary, many Americans still believe that police are “under attack” because people are demanding that they face consequences for their actions. Many still do not, but this has not stopped passionate social movements like “Blue Lives Matter,” which arose as a direct counter movement to Black Lives Matter, castigating their members as liars, thugs, and thieves and upholding killer cops as heroes. Their website’s mission is to cover news from the “correct” perspective, i.e. the police officers’, and to condemn anyone who speaks or acts against them. This is both tone-deaf and racist, for a variety of reasons. “Blue lives” are not under attack at all; societally, all the power belongs to the police, who can kill (largely black) people, regardless of offence, and face absolutely no repercussions. Demanding accountability is not oppressive or unfair in any way, and it is disgusting that asking for due process and justice is apparently “reverse racist” to so many people. It is also concerning that police set themselves up as the public’s defender against these supposed criminals, whose only crime is demanding that the actual killers go to trial. Castigating the media for reflecting the perspective of the majority is more in line with a police state than a democratic one. Police are people, and their profession does not make them any better than the average citizen, even if that citizen is a young black man in a hoodie. They should protect the people, not terrorize them, and if they do, they should strive to fix it, not attack the ones calling for positive change.

The American justice system is, of course, necessary, but it should never be a necessary evil. Some may say that true justice is almost impossible to maintain, but the fact of the matter is that this nation could be doing a lot better. There needs to be more accountability, harsher punishments for trained and armed police instead of harsher punishments for untrained civilians, and safe resources and channels through which victims of police violence can get recompense. The prison industry needs to get far less money than it does, so that they will stop filling their cells with people convicted of minor charges. Measures that result in less loss of life for civilians needs to be put in place and enforced. Lastly, the “thin blue line” needs to stop being worshipped, and instead subject to the scrutiny and blame that its victims are subjected to even after their deaths.

Bibliography

“42 Shocking Police Brutality Statistics.” Vittana.org, Vittana, 22 Feb. 2017, vittana.org/42-shocking-police-brutality-statistics. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

“About Us.” Blue Lives Matter, 11 Jan. 2017, bluelivesmatter.blue/organization/#history. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Ali, Safia Samee, and William Sherman. “Why Police Officers Often Aren’t Convicted for Using Lethal Force.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 30 July 2016, www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-police-officers-often-aren-t-convicted-using-lethal-force-n619961. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Balsamini, Dean, and Kathianne Boniello. “St. Louis cops trample, arrest woman at protest.” New York Post, New York Post, 17 Sept. 2017, nypost.com/2017/09/16/st-louis-cops-trample-woman-at-protest/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

“Police violence map.” Mapping Police Violence, mappingpoliceviolence.org/. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Torjee, Diana. “Sexual Assault by Police Officers Is Even More Common Than You Think.” Broadly, VICE, 2 Nov. 2015, broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/gvze7q/sexual-assault-by-police-officers-is-even-more-common-than-you-think. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Willingham, AJ. “How the iconic ‘Whose streets? Our streets!’ chant has been co-Opted.” CNN, Cable News Network, 19 Sept. 2017, www.cnn.com/2017/09/19/us/whose-streets-our-streets-chant-trnd/index.html. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A response to Roxane Gay’s “Peculiar Benefits”

Roxane Gay’s “Peculiar Benefits” is a good starting point for people who are unfamiliar with the concept of privilege. It outlined what privilege is, gave examples, explained all the different kinds of privilege and that most people are privileged in some way, and, most importantly, explained that having privilege does not negate or devalue the struggles of the privileged person in question. However, the essay’s attitude towards marginalized people and people involved in the social justice community was at times dismissive or even condemnatory, whereas it never highlighted the faults or insulting/aggressive attitudes of the people on the other side of the equation.

Firstly, Roxane Gay says that the word privilege is overused, and has become almost meaningless. This was not caused by people who fight for social justice. In fact, appropriation and distortion of social justice terms is a tried and true method of fighting against it, parodying their words and efforts to make them look ridiculous and ineffectual. Anti social justice people will pick a word and use it ironically in order to insult, belittle, and delegitimize the people who use them correctly. Some examples would be “triggered” or “did you just assume my gender?”

Gay goes on to condemn the people who point out other people’s privilege, saying that they used it as an attack on the privileged person. This is nowhere near as common as she implied it to be. True, privileged people often respond as if it is an attack, delegitimizing their hardships and suffering, and sometimes use that as a chance to attack the marginalized person and delegitimize their suffering, and will sometimes even take that opportunity to say that they are not marginalized at all, and it is instead due to their “insulting and inflammatory” language and attitude. However, pointing out privilege is not an attack, nor is it “oppression olympics.” It is highlighting that, in a discussion about marginalization, the privileged person has not experienced it, and should not speak as if they are somehow just as, or more, knowledgeable about it.

Gay also engages in some tone policing, saying that marginalized people use privilege as a way to “strike back” or silence people. This is blatantly unfair. She goes to great lengths to soothe the egos of people who are angry about being privileged, but does nothing but point out that oppressed people are angry about being oppressed and should not take it out on others. Marginalized people’s anger is often blown out of proportion and made to seem “dangerous” or “disrespectful” (one example being the “take a knee” demonstrations in the NFL), but she says nothing about the privileged people who are enraged and attacking those marginalized people for speaking out in any way, including pointing out privilege. It is not an attack; it is asking people to acknowledge the ways that they have benefitted from their privilege, and keep that in mind when engaging in discourse.

Condemning the oppressed as being “too angry” or acting “just as bad” as their oppressors has always been used to destabilize and silence social movements. Pointing out privilege is not anything like that, and equating the two is blatantly unfair. Marginalized people cannot marginalize the ones who marginalize them. They should be allowed to have their voices heard and emphasized. They should be allowed to ask uneducated, privileged people to step back and listen, and acknowledge their privilege if they have something relevant they want to share. They do not owe privileged people their attention and effort, just as privileged people do not owe them their attention and effort. Expect from them what you expect of their privileged counterparts.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chicago U Prompt

In French, there is no difference between "conscience" and "consciousness." In Japanese, there is a word that specifically refers to the splittable wooden chopsticks you get at restaurants. The German word “fremdschämen” encapsulates the feeling you get when you’re embarrassed on behalf of someone else. All of these require explanation in order to properly communicate their meaning, and are, to varying degrees, untranslatable. Choose a word, tell us what it means, and then explain why it cannot (or should not) be translated from its original language.

“Goya” is an Urdu word meaning the complete transportation and suspension of disbelief when a fantasy seems so realistic that it temporarily becomes your reality. It is usually associated with skilled storytelling. While this concept is one that everyone who regularly consumes works of fiction has experienced, it has no equivalent in the English language.

For having such a complex meaning, the word itself is remarkably simple; only two syllables, both of which are easy to pronounce, together or separately. Any number of children just learning to talk could say it, perhaps even of their own accord, without any idea of what it signifies. This simplicity, in part, is what makes “goya” stand out amongst its peers. There are many “untranslatable” words in the world’s many different languages, the example “fremdschämen” being one of them, but almost all of them are lengthy, and made up of individual parts with unique standalone meanings, or even a more literal translation.

However, to Urdu-speaking peoples, “goya” is such an intrinsic concept that they had no need to mash two simpler words together to convey the meaning they were trying to capture. And what is language, what are linguistics, but a way of telling a story? It does not have to be your story; it does not even have to be fictional. However, the greatest purpose and use of language is to convey a narrative. When it comes to words, there is no such thing as objectivity. The very vocabulary you use and the structure of your sentences influence the meaning that the speaker or writer or even signer tells to others. Even so, we think and interact almost entirely with language. Every person tells a story whenever they open their mouths, and that story is, for at least a moment, the listener’s reality. And what is that but the greatest ‘goya’ of all?

Because of the inherently biased, perhaps even fictional, nature of language, it is impossible to truly translate anything, when words themselves have no absolute meaning. When it comes to words like “goya,” which are so perfectly encapsulatory, and yet untrue in the way that all words are untrue, translation is almost a diminishment.

I feel that we all make each other feel “goya,” but it never stops. How well can you truly know another person? How well can another person truly know you? Would you even want to truly know another person, or vice versa? Is the “translation” of the self a diminishment?

In many ways, I want to be a storyteller that induces “goya” in my listeners, with the fantasy being myself. I want to always present my best self, to be the best that I can be, even if, in my heart of hearts, I am not as confident or patient or generous as I seem. I want their truth, their perception of me, to be different -- to be better -- than my own. This is partially due to my own self-esteem and struggles with loving myself, because if everyone perceived my relatively minor flaws the way that I did, they would be the only things they ever noticed about me. Is my own self image, my own form of impostor syndrome, yet another facet of ‘goya’? I suppose that I cannot know; I suppose that ‘goya’ is universal.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bring Justice to Criminal Justice

Almost everyone can agree that the concept of law enforcement is a good one. The idea of people out there working tirelessly to punish evildoers and keep citizens safe is reassuring. It is a narrative that is upheld by the part of the population that rarely has to worry about getting targeted and victimized: white, wealthy, straight, cisgender people. The narrative varies amongst other white people, depending on how well they fit into all those categories, but as a whole, they are taught to consider police to be heroic and the justice system to be almost infallible -- and for many of them, that may be the case. It is not so for the rest of the population. The American criminal justice system is deeply flawed, and does as much (or more) harm as good.

One of the most visible faults of the criminal justice system as a whole is police brutality. Police officers can literally get away with murder, provided that their victim is a person of color. Even if they are caught on camera, courts will often fail to indict. This is because police are well-known to be reluctant to testify against or prosecute their own, and judges, jurors, and prosecutors have more faith in their testimonies due to their profession. Many witnesses are also unlikely to testify if they are facing criminal charges, as it will hurt their chances in their own legal battles. Police involved in killings are indicted less than 1% of the time. Comparatively, civilians are indicted at a rate of 90%. From 2005 to 2014, thousands of officers shot and killed people, but only 48 were ever charged with manslaughter in that same time frame. How is this at all just? They rarely face disciplinary action from their superiors, often getting paid leave until any media attention dies down. Imagine if your sister or father’s murderer got a paid vacation for his trouble! 99% of these cases in 2015 have not resulted in an officer’s conviction. But cases without media or court attention are far more insidious -- and far more prevalent. 52% of police officers report that it is not unusual for law enforcement officials to ignore the improper conduct of others, 61% say that they do not always report serious abuse that has been observed by other officers, and 84% of police officers stated in a survey that they have witnessed another officer using more force than necessary. These numbers are appalling. If this many have openly admitted to this, imagine how many did not. Statistically speaking, it is unlikely that every single instance of unnecessary violence perpetrated by police was an honest mistake made with good intentions, given the sheer number and scope of these instances, many of them victimizing the elderly and children. For an example, look no further than recent events in St. Louis, where riot police knocked over an old woman and walked over her, pepper spraying the people trying desperately to get to her and help her back up. There is no way they could feasibly have thought that assaulting that elderly woman was the best way to protect and serve. Even if that situation could be misconstrued as an innocent mistake, their attitude toward their stations and actions was made clear when they appropriated the “Whose streets? Our streets!” chant. The chant was originally used by people protesting for immigrant, LGBT, and black people’s rights -- often for the right to simply exist in a public space without being in danger of violence or death. When St. Louis police took that chant, when they themselves are not oppressed or victimized, and are often perpetrators of these injustices, they sent a clear message: they owned the city, and the protesters could not have the rights and freedoms for which they were marching. It goes without saying that their behavior is both terrifying and disgusting.

However, physical violence is not the only way police harm the vulnerable -- sexual assault is the second most common form of police misconduct. There are a few reasons that it is not as widely discussed, such as the stigma of discussing sex crimes, fear or shame preventing a victim from coming forward, fear that it will happen again, or fear of retaliation by their victimizer. Police predators will also target the most vulnerable demographics, with most victims being girls of color. According to research by Dr. Phil Stinson, victims are also “disproportionately underage,” meaning that the majority of victims are legally children. Police are meant to protect these people, but instead they use their positions to prey upon vulnerable women and kids. This is not the only way that they exploit the vulnerable, as a year long investigation by the Associated Press found “about 1,000 officers who lost their badges in a six-year period for rape, sodomy and other sexual assault; sex crimes that included possession of child pornography; or sexual misconduct such as propositioning citizens or having consensual but prohibited on-duty intercourse.” If police are willing to let their fellow officers’ misconduct slide, as shown above in regards to police brutality, who knows how many more have done any number of these things and gotten away with it? Clearly, they should not just take their badges. These people are criminals, not protectors, and they deserve to be in prison.

Despite all evidence to the contrary, many Americans still believe that police are “under attack” because people are demanding that they face consequences for their actions. Many still do not, but this has not stopped passionate social movements like “Blue Lives Matter,” which arose as a direct counter movement to Black Lives Matter, castigating their members as liars, thugs, and thieves and upholding killer cops as heroes. Their website’s mission is to cover news from the “correct” perspective, i.e. the police officers’, and to condemn anyone who speaks or acts against them. This is both tone-deaf and racist, for a variety of reasons. “Blue lives” are not under attack at all; societally, all the power belongs to the police, who can kill (largely black) people, regardless of offence, and face absolutely no repercussions. Demanding accountability is not oppressive or unfair in any way, and it is disgusting that asking for due process and justice is apparently “reverse racist” to so many people. It is also concerning that police set themselves up as the public’s defender against these supposed criminals, whose only crime is demanding that the actual killers go to trial. Castigating the media for reflecting the perspective of the majority is more in line with a police state than a democratic one. Police are people, and their profession does not make them any better than the average citizen, even if that citizen is a young black man in a hoodie. They should protect the people, not terrorize them, and if they do, they should strive to fix it, not attack the ones calling for positive change.

The American justice system is, of course, necessary, but it should never be a necessary evil. Some may say that true justice is almost impossible to maintain, but the fact of the matter is that this nation could be doing a lot better. There needs to be more accountability, harsher punishments for trained and armed police instead of harsher punishments for untrained civilians, and safe resources and channels through which victims of police violence can get recompense. The prison industry needs to get far less money than it does, so that they will stop filling their cells with people convicted of minor charges. Measures that result in less loss of life for civilians needs to be put in place and enforced. Lastly, the “thin blue line” needs to stop being worshipped, and instead subject to the scrutiny and blame that its victims are subjected to even after their deaths.

Bibliography

“42 Shocking Police Brutality Statistics.” Vittana.org, Vittana, 22 Feb. 2017, vittana.org/42-shocking-police-brutality-statistics. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

“About Us.” Blue Lives Matter, 11 Jan. 2017, bluelivesmatter.blue/organization/#history. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Ali, Safia Samee, and William Sherman. “Why Police Officers Often Aren't Convicted for Using Lethal Force.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 30 July 2016, www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-police-officers-often-aren-t-convicted-using-lethal-force-n619961. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Balsamini, Dean, and Kathianne Boniello. “St. Louis cops trample, arrest woman at protest.” New York Post, New York Post, 17 Sept. 2017, nypost.com/2017/09/16/st-louis-cops-trample-woman-at-protest/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

“Police violence map.” Mapping Police Violence, mappingpoliceviolence.org/. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Torjee, Diana. “Sexual Assault by Police Officers Is Even More Common Than You Think.” Broadly, VICE, 2 Nov. 2015, broadly.vice.com/en_us/article/gvze7q/sexual-assault-by-police-officers-is-even-more-common-than-you-think. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Willingham, AJ. “How the iconic 'Whose streets? Our streets!' chant has been co-Opted.” CNN, Cable News Network, 19 Sept. 2017, www.cnn.com/2017/09/19/us/whose-streets-our-streets-chant-trnd/index.html. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greek fire is a term that anybody who has an interest in medieval history is aware of. First used in 678 CE, it routed an entire Arab fleet, delivered only by a tiny Eastern Roman Empire flotilla. Its existence is commonly credited as the reason the empire lasted so long, and they used it to win battles for over seven centuries. The perfect ancient weapon, one so infamous that the most common response to it was to flee or, if that was impossible, pray. However, its destructive powers are not the only reason why it is so infamous to this day. Its recipe was such a closely guarded secret that it was never written down -- and so it was lost to time and memory.

What was in it? Historians can only theorize. Even people who managed to capture samples, as rarely as that happened, were unable to fully recreate it. All we can rely on are historical records in which fear and speculation are rampant. Was it truly as effective and fearsome as ancient people believed it to be?

In order to get a better idea of what exactly was necessary for “liquid flames” that could not be put out by water, I talked to our resident Chemistry teacher, Ms. Parameswaran. She told me that three things are necessary for a combustion reaction (fire): a fuel source, typically a hydrocarbon; oxygen; and something to ignite it, like heat or a spark. Flames cannot burn when the fuel is separated from oxygen, something commonly accomplished by submerging it in water or smothering it.

However, neither of those things, according to record, could stop Greek fire. The only things that could extinguish it were vinegar, sand, and oddly enough, urine. It actually burnt hotter when it came into contact with water, to the point that some sources claim that water actually ignited it. Ms. Parameswaran and I theorized that it might not have been just a combustion reaction, but an exothermic reaction, as well. Exothermic reactions create heat without flames, and there are plenty of things that react when they come into contact with water. Quicklime is often thought to be a key ingredient of Greek fire, and I agree with those assessments for one crucial reason: quicklime becomes very hot when it touches water. A person submerged in the ocean would certainly get chemical burns from quicklime, even if they were not truly on fire. This may be why people believed that the flames could burn underwater -- how else would the sailors burn, if not from fire?

After this, I figured that I had to go more in-depth. I visited the Southeast Library, where the librarian at the information desk told me how to access a bunch of online databases full of ebooks, articles, and other sources, all of which had been vetted. She recommended a couple of different databases, some for simple research, and some specifically meant to help researchers craft an argument by providing opposing viewpoints on the topics they offer information on.

I found that a few other commonly agreed-upon ingredients were naphtha (a form of petroleum), sulphur, and resin. Naphtha and sulphur would easily form the flames once ignited, and sulphur fires move extremely quickly, which was another property of Greek fire. Another interesting effect sulphur fire has is that it produces sulphur dioxide, a gas that produces sulphuric acid when it comes into contact with water -- including the moisture in your lungs. Even after submerging themselves in the sea, enemy sailors would still be burning, inside and out. The resin was likely used to thicken the mixture and make it sticky -- thus why Greek fire stuck to everything it touched; and once it touched something, almost nothing would be able to put it out. Additionally, if you’re familiar with outdoor survival tips, you’ll also know that pine resin is known as “nature’s fire starter.” It catches and spreads very quickly, which is one of the reasons why forest fires happen so easily and are so important to prevent.

After researching its possible components, it is very easy to see why Greek fire is sometimes called “the first modern chemical weapon.” In later years, the Eastern Romans managed to put it into grenades and even flamethrowers. Both modern weapons, as well as napalm, were inspired by their technology and ingenuity. Greek fire was a shaping factor in the history of the world -- had Constantinople fallen to the Arabs in the 600s, they could have conquered most or all of Western Europe, which had few governments strong enough or armies large enough to combat them. History could have looked very different, were it not for a Syrian refugee and architect named Kallinikos, who created the ancient world’s equivalent of the atomic bomb. His invention is the reason why the world is the way it is today. I’ll let you decide whether or not that’s a good thing.

Bibliography

Alchin, Linda. “Greek Fire.” Medieval Life and Times, www.medieval-life-and-times.info/medieval-weapons/greek-fire.htm.

All That Is Interesting on December 12, 2017. “Greek Fire: One of History's Best-Kept Military Secrets.” All That Is Interesting, 12 Dec. 2017, all-that-is-interesting.com/greek-fire.

All That Is Interesting on December 12, 2017. “Greek Fire: One of History's Best-Kept Military Secrets.” All That Is Interesting, 12 Dec. 2017, all-that-is-interesting.com/greek-fire.

Cartwright, Mark. “Greek Fire.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia, 14 Nov. 2017, www.ancient.eu/Greek_Fire/.

Gilbert, Steven. “Greek Fire.” Toxipedia, Atlassian Confluence and Zen Foundation, 30 May 2014, www.toxipedia.org/display/toxipedia/Greek Fire.

Knight, Judson, and Judy Galens. Middle Ages Reference Library. Vol. 1, Gale, 2001. Gale Virtual Reference Library, go.galegroup.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=T003&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=7&docId=GALE%7CCX3426200014&docType=Topic overview&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=&prodId=GVRL&contentSet=GALE%7CCX3426200014&searchId=R1&userGroupName=dclib_main&inPS=true.

Network, Warfare History, et al. “Greek Fire: The Byzantine Empire's Secret Weapon the Ancient World Feared.” The National Interest, The Center for the National Interest, 2 June 2017, nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/greek-fire-the-byzantine-empires-secret-weapon-the-ancient-20955.

Potenza, Alessandra. “This blue sulfur hellfire in Wyoming is mesmerizing - and toxic.” The Verge, Vox Media, 10 July 2017, www.theverge.com/2017/7/10/15947592/sulfur-mound-fire-video-worland-wyoming.

#greek fire#eastern roman empire#medieval history#medieval weaponry#historical mystery#history#military history

9 notes

·

View notes