R.O.U.S., Indigo. INFJ. They/Them. Draws weird and cute stuff. Anti-malnutrition, Anti-toxic-schools, Pro-massive-compensations-for-loss-of-health-due-to-abuse.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The more I think on it, and I know this greatly differs from what people have come to expect in recent years, but to me a TTRPG with no adventure modules is like booting up a video game and finding out the devs didn’t make any levels. Like I wanted to play this but I guess we’ll have to wait until someone in the group, who may have never played the game before, spends a not-insignificant amount of their free time in the level-editor throwing something together for us to play.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In a notification sent to Congress over the weekend, Immigration and Customs Enforcement revealed that a 75-year-old Cuban national named Isidro Perez died while in ICE custody on June 26. The death, which appears to have been caused by a heart attack, is “still under investigation,” according to the notification, which was sent our way by a congressional aide. Obviously, the man’s age immediately makes it look odd that he was in ICE detention in the first place. But here’s something else that’s striking about this case: According to the ICE note, the man was first paroled into the United States in 1966. Yes, you read that right. The man has been here for almost 60 years—and he appears to have been around 16 years old when he first arrived from Fidel Castro’s Cuba.”

— Why Did a 75-Year-Old Man in Poor Health Just Die in ICE Custody?

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

this might sound stupid but I can’t help but believe that the new wave of “birth control is actually horrible for your body, you need to get off it immediately” misinformation from influencers and the ‘natural cycle tracking’ apps suddenly being advertised is a sneaky underhanded way of causing more unplanned pregnancies that people now cannot abort. now is possibly the worst time ever to turn towards ‘natural family planning’

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s a “public internet?”

I'm in the home stretch of my 24-city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in LONDON (July 1) with TRASHFUTURE'S RILEY QUINN and then a big finish in MANCHESTER on July 2.

The "Eurostack" is a (long overdue) project to publicly fund a European "stack" of technology that is independent from American Big Tech (as well as other powers' technology that has less hold in Europe, such as Chinese and Russian tech):

https://www.euro-stack.info/

But "technological soveriegnty" is a slippery and easily abused concept. Policies like "national firewalls" and "data localization" (where data on a country's population need to be kept on onshore servers) can be a means to different ends. Data localization is important if you want to keep an American company from funneling every digital fact about everyone in your country to the NSA. But it's also a way to make sure that your secret police can lay hands on population-scale data about anyone they might want to kidnap and torture:

https://doctorow.medium.com/theyre-still-trying-to-ban-cryptography-33aa668dc602

At its worst, "technological sovereignty" is a path to a shattered internet with a million dysfunctional borders that serve as checkpoints where thuggish customs inspectors can stop you from availing yourself of privacy-preserving technology and prevent you from communicating with exiled dissidents and diasporas.

But at its best, "technological sovereignty" is a way to create world-girding technology that can act as an impartial substrate on which all manner of domestic and international activities can play out, from a group of friends organizing a games night, to scientists organizing a symposium, to international volunteer corps organizing aid after a flood.

In other words, "technological sovereignty" can be a way to create a public internet that the whole public controls – not just governments, but also people, individuals who can exercise their own technological self-determination, controlling crucial aspects of their own technology usage, like "who will see this thing I'm saying?" and "whose communications will I see, and which ones can I block?"

A "public internet" isn't the same thing as "an internet that is operated by your government," but you can't get a public internet without government involvement, including funding, regulation, oversight and direct contributions.

Here's an example of different ways that governments can involve themselves in the management of one part of the internet, and the different ways in which this will create more or less "public" internet services: fiber optic lines.

Fiber is the platinum standard for internet service delivery. Nothing else comes even close to it. A plastic tube under the road that is stuffed with fiber optic strands can deliver billions of times more data than copper wires or any form of wireless, including satellite constellations like Starlink:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/03/30/fight-for-44/#slowpokes

(Starlink is the most antifuturistic technology imaginable – a vision of a global internet that gets slower and less reliable as more people sign up for it. It makes the dotcom joke of "we lose money on every sale but make it up in volume" look positively bankable.)

The private sector cannot deliver fiber. There's no economical way for a private entity to secure the rights of way to tear up every street in every city, to run wires into every basement or roof, to put poles on every street corner. Same goes for getting the rights of way to string fiber between city limits across unincorporated county land, or across the long hauls that cross national and provincial or state borders.

Fiber itself is cheap like borscht – it's literally made out of sand – but clearing the thicket of property rights and political boundaries needed to get wire everywhere is a feat that can only be accomplished through government intervention.

Fiber's opponents rarely acknowledge this. They claim, instead, that the physical act of stringing wires through space is somehow transcendentally hard, despite the fact that we've been doing this with phone lines and power cables for more than a century, through the busiest, densest cities and across the loneliest stretches of farmland. Wiring up a country is not the lost art of a fallen civilization, like building pyramids without power-tools or embalming pharoahs. It's something that even the poorest counties in America can manage, bringing fiber across forbidden mountain passes on the back of a mule named "Ole Bub":

https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-one-traffic-light-town-with-some-of-the-fastest-internet-in-the-us

When governments apply themselves to fiber provision, you get fiber. Don't take my word for it – ask Utah, a bastion of conservative, small-government orthodoxy, where 21 cities now have blazing fast 10gb internet service thanks to a public initiative called (appropriately enough) "Utopia":

https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/16/symmetrical-10gb-for-119/#utopia

So government have to be involved in fiber, but how should they involve themselves in it? One model – the worst one – is for the government to intervene on behalf of a single company, creating the rights of way for that company to lay fiber in the ground or string it from poles. The company then owns the network, even though the fiber and the poles were the cheapest part of the system, worth an unmeasurably infinitesimal fraction of the value of all those rights of way.

In the worst of the worst, the company that owns this network can do anything they want with its fiber. They can deny coverage to customers, or charge thousands of dollars to connect each new homes to the system. They can gouge on monthly costs, starve their customer service departments or replace them with mindless AI chatbots. They can skimp on maintenance and keep you waiting for days or weeks when your internet goes out. They can lard your bill with junk fees, or force you to accept pointless services like landlines and cable TV as a condition of getting the internet.

They can also play favorites with local businesses: maybe they give great service to every Domino's pizza place at knock-down rates, and make up for it by charging extra to independent pizza parlors that want to accept internet orders and stream big sports matches on the TV over the bar.

They can violate Net Neutrality, slowing down your connection to sites unless their owners agree to pay bribes for "premium carriage." They can censor your internet any way they see fit. Remember, corporations – unlike governments – are not bound by the First Amendment, which means that when a corporation is your ISP, they can censor anything they feel like:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/15/useful-idiotsuseful-idiots/#unrequited-love

Governments can improve on this situation by regulating a monopoly fiber company. They can require the company to assume a "universal service" mandate, meaning they must connect any home or business that wants it at a set rate. Governments can ban junk fees, set minimum standards for customer service and repair turnarounds, and demand neutral carriage. All of this can improve things, though its a lot of work to administer, and the city government may lack the resources and technical expertise to investigate every claim of corporate malfeasance, and to perform the technical analysis to evaluate corporate excuses for slow connections and bungled repairs.

That's the worst model: governments clear the way for a private monopolist to set up your internet, offering them a literally priceless subsidy in the form of rights of way, and then, maybe, try to keep them honest.

Here's the other extreme: the government puts in the fiber itself, running conduit under all the streets (either with its own crews or with contract crews) and threading a fiber optic through a wall of your choice, terminating it with a box you can plug your wifi router into. The government builds a data-center with all the necessary switches for providing service to you and your neighbors, and hires people to offer you internet service at a reasonable price and with reasonable service guarantees.

This is a pretty good model! Over 750 towns and cities – mostly conservative towns in red states – have this model, and they're almost the only people in America who consistently describe themselves as happy with their internet service:

https://ilsr.org/articles/municipal-broadband-skyrocket-as-alternative-to-private-models/

(They are joined in their satisfaction by a smattering of towns served by companies like Ting, who bought out local cable companies and used their rights of way to bring fiber to households.)

This is a model that works very well, but can fail very badly. Municipal governments can be pretty darned kooky, as five years of MAGA takeovers of school boards, library boards and town councils have shown, to say nothing of wildly corrupt big-city monsters like Eric Adams (ten quintillion congratulations to Zohran Mamdani!). If there's one thing I've learned from the brilliant No Gods No Mayors podcast, it's that mayors are the weirdest people alive:

https://www.patreon.com/collection/869728?view=condensed

Remember: Sarah Palin got her start in politics as mayor of Wasilla, Alaska. Do you want to have to rely on Sarah Palin for your internet service?

https://www.patreon.com/posts/119567308?collection=869728

How about Rob Ford? Do you want the crack mayor answering your tech support calls? I didn't think so:

https://www.patreon.com/posts/rob-ford-part-1-111985831

But that's OK! A public fiber network doesn't have to be one in which the government is your only choice for ISP. In addition to laying fiber and building a data-center and operating a municipal ISP, governments can also do something called "essential facilities sharing":

https://transition.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Common_Carrier/Orders/1999/fcc99238.pdf

Governments all over the world did this in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and some do it still. Under an essential facilities system, the big phone company (BT in the UK, Bell in Canada, AT&T and the Baby Bells in the USA) were required to rent space to their competitors in their data centers. Anyone who wants to set up an ISP can install their own switching gear at a telephone company central office and provide service to any business or household in the country.

If the government lays fiber in your town, they can both operate a municipal fiber ISP and allow anyone else to set up their own ISP, renting them shelf-space at the data-center. That means that the town college can offer internet to all its faculty and students (not just the ones who live in campus housing), and your co-op can offer internet service to its members. Small businesses can offer specialized internet, and so can informal groups of friends. So can big companies. In this model, everyone is guaranteed both the right to get internet access and the right to provide internet access. It's a great system, and it means that when Mayor Sarah Palin decides to cut off your internet, you don't need to sue the city – you can just sign up with someone else, over the same fiber lines.

That's where essential facilities sharing starts, but that's not where it needs to stop. When the government puts conduit (plastic tubes) in the ground for fiber, they can leave space for more fiber to fished through, and rent space in the conduit itself. That means that an ISP that wants to set up its own data center can run physically separate lines to its subscribers. It means that a university can do a point-to-point connection between a remote scientific instrument like a radio telescope and the campus data-center. A business can run its own lines between branch offices, and a movie studio can run dedicated lines from remote sound-stages to the edit suites at its main facility.

This is a truly public internet service – one where there is a publicly owned ISP, but also where public infrastructure allows for lots of different kinds of entities to provide internet access. It's insulated from the risks of getting your tech support from city hall, but it also allows good local governments to provide best-in-class service to everyone in town, something that local governments have a pretty great track record with.

The Eurostack project isn't necessarily about fiber, though. Right now, Europeans are thinking about technological sovereignty through the lens of software and services. That's fair enough, though it does require some rethinking of the global fiber system, which has been designed so that the US government can spy on and disconnect every other country in the world:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/10/weaponized-interdependence/#the-other-swifties

Just as with the example of fiber, there are a lot of ways the EU and member states could achieve "technological sovereignty." They could just procure data-centers, server software, and the operation of social media, cloud hosting, mobile OSes, office software, and other components of Europeans' digital lives from the private sector – sort of like asking a commercial operator to run your town's internet service.

The EU has pretty advanced procurement rules, designed to allow European governments to buy from the private sector while minimizing corruption and kickbacks. For example, there's a rule that the lowest priced bid that conforms to all standards needs to win the contract. This sounds good (and it is, in many cases) but it's how Newag keeps selling trains in Poland, even after they were caught boobytrapping their trains so they would immobilize themselves if the operator took them for independent maintanance:

https://media.ccc.de/v/38c3-we-ve-not-been-trained-for-this-life-after-the-newag-drm-disclosure

The EU doesn't have to use public-private partnerships to build the Eurostack. They could do it all themselves. The EU and/or member states could operate public data centers. They could develop their own social media platforms, mobile OSes, and apps. They could be the equivalent of the municipal ISP that offers fast fiber to everyone in town.

As with public monopoly ISPs, this is a system that works well, but fails badly. If you think Elon Musk is a shitty social media boss, wait'll you see the content moderation policies of Viktor Orban – or Emmanuel Macron:

https://jacobin.com/2025/06/france-solidarity-urgence-palestine-repression

Publicly owned data centers could be great, but also, remember that EU governments have never given up on their project of killing working encryption so that their security services can spy on everyone. Austria's doing it right now!

https://www.yahoo.com/news/austrian-government-agrees-plan-allow-150831232.html

Ever since Snowden, EU governments have talked a good line about the importance of digital privacy. Remember Angela Merkel's high dudgeon about how her girlhood in the GDR gave her a special horror of NSA surveillance?

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-24647268

Apparently, Merkel managed to get over her horror of mass surveillance and back total, unaccountable, continuous digital surveillance over all of Germany:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/24/germanys-new-surveillance-laws-raise-privacy-concerns

So there's good reasons to worry about having your data – and your apps – hosted in an EU cloud.

To create a European public internet, it's neither necessary nor desirable to have your digital life operated by the EU and its member states, nor by its private contractors. Instead, the EU could make Eurostack a provider of technological public goods.

For example, the EU could work to improve federated social media systems, like Mastodon and Bluesky. EU coders could contribute to the server and client software for both. They could participate in future versions of the standard. They could provide maintenance code in response to bug reports, and administer bug bounties. They could create tooling for server administrators, including moderation tools, both for Mastodon and for Bluesky, whose "composable moderation" system allows users to have the final say over their moderation choices. The EU could perform and/or fund labelling work to help with moderation.

The EU could also provide tooling to help server administrators stand up their own independent Mastodon and Bluesky servers. Bluesky needs a lot of work on this, still. Bluesky's CTO has got a critical piece of server infrastructure to run on a Raspberry Pi for a few euros per month:

https://justingarrison.com/blog/2024-12-02-run-a-bluesky-pds-from-home/

Previously, this required a whole data center and cost millions to operate, so this is great. But this now needs to be systematized, so that would-be Bluesky administrators can download a package and quickly replicate the feat.

Ultimately, the choice of Mastodon or Bluesky shouldn't matter all that much to Europeans. These standards can and should evolve to the point where everyone on Bluesky can talk to everyone on Mastodon and vice-versa, and where you can easily move your account from one server to another, or one service to another. The EU already oversees systems for account porting and roaming on mobile networks – they can contribute to the technical hurdles that need to be overcome to bring this to social media:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/12/14/fire-exits/#graceful-failure-modes

In addition to improving federated social media, the EU and its member states can and should host their own servers, both for their own official accounts and for public use. Giving the public a digital home is great, especially if anyone who chafes at the public system's rules can hop onto a server run by a co-op, a friend group, a small business or a giant corporation with just a couple clicks, without losing any of their data or connections.

This is essential facilities sharing for services. Combine it with public data centers and tooling for migrating servers from and to the public server to a private, or nonprofit, or co-op data-center, and you've got the equivalent of publicly available conduit, data-centers, and fiber.

In addition to providing code, services and hardware, the EU can continue to provide regulation to facilitate the public internet. They can expand the very limited interoperability mandates in the Digital Markets Act, forcing legacy social media companies like Meta and Twitter to stand up APIs so that when a European quits their service for new, federated media, they can stay in touch with the friends they left behind (think of it as Schengen for social media, with guaranteed free movement):

https://www.eff.org/interoperablefacebook

With the Digital Service Act, the EU has done a lot of work to protect Europeans from fraud, harassment and other online horribles. But a public internet also requires protections for service providers – safe harbors and carve outs that allow you to host your community's data and conversations without being dragged into controversies when your users get into flamewars with each other. If we make the people who run servers liable for their users' bad speech acts, then the only entities that will be able to afford the lawyers and compliance personnel will be giant American tech companies run by billionaires like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

https://pluralistic.net/2020/12/04/kawaski-trawick/#230

A "public internet" isn't an internet that's run by the government: it's a system of publicly subsidized, publicly managed public goods that are designed to allow everyone to participate in both using and providing internet services. The Eurostack is a brilliant idea whose time arrived a decade ago. Digital sovereignty projects are among the most important responses to Trumpism, a necessary step to build an independent digital nervous system the rest of the world can use to treat the USA as damage and route around it. We can't afford to have "digital soveriegnty" be "national firewalls 2.0" – we need a public internet, not 200+ national internets.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/06/25/eurostack/#viktor-orbans-isp

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

tbh I do still think of California as a sort of otherworld. I know everybody shits on it, there's fire and traffic and "S*licon V*lley" and so on.

But a part of me will always see a Mediterranean neverland tiled for thousands of miles in every direction with modernist university buildings full of late-20th-century academics working on very exciting stuff. They all look somewhat like Jacob Bronowski.

In the uttermost West, beneath the film grain, the sun sets on the golden gates of a Pacific world, on science fiction writers and beautiful, racially diverse neo-hippies driving down the beach. They talk of quantum shamans and vibrations and it's all nonthreatening, all a bit Douglas Adams, not at all serious, and maybe...

In California, I dream, there are young and old women who believe in dolphins. I used to believe in dolphins.

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surveillance pricing lets corporations decide what your dollar is worth

I'm in the home stretch of my 24-city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in LONDON (July 1) with TRASHFUTURE'S RILEY QUINN and then a big finish in MANCHESTER on July 2.

Economists praise "price discrimination" as "efficient." That's when a company charges different customers different amounts based on inferences about their willingness to pay. But when a company sells you something for $2 that someone else can buy for $1, they're revaluing the dollars in your pocket at half the rate of the other guy's.

That's not how economists see it, of course. When a hotel sells you a room for $50 that someone else might get charged $500 for, that's efficient, provided that the hotelier is sure no $500 customers are likely to show up after you check in. The empty room makes them nothing, and $50 is more than nothing. There's a kind of metaphysics at work here, in which the room that is for sale at $500 is "a hotel room you book two weeks in advance and are sure will be waiting for you when you check in" while the $50 room is "a hotel room you can only get at the last minute, and if it's not available, you're sleeping in a chair at the Greyhound station."

But what if you show up at the hotel at 9pm and the hotelier can ask a credit bureau how much you can afford to pay for the room? What if they can find out that you're in chemotherapy, so you don't have the stamina to shop around for a cheaper room? What if they can tell that you have a 5AM flight and need to get to bed right now? What if they charge you more because they can see that your kids are exhausted and cranky and the hotel infers that you'll pay more to get the kids tucked into bed? What if they charge you more because there's a wildfire and there are plenty of other people who want the room?

The metaphysics of "room you booked two weeks ago" as a different product from "room you're trying to book right now" break down pretty quickly once you factor in the ability of sellers to figure out how desperate you are – or merely how distracted you are – and charge accordingly. "Surveillance pricing" is the practice of spying on you to figure out how much you're willing to spend – because you're wealthy, because you're desperate, because you're distracted, because it's payday – and charging you more:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/05/your-price-named/#privacy-first-again

For example, a McDonald's ventures portfolio company called Plexure offers drive-through restaurants the ability to raise the price of your regular order based on whether you've recently received your paycheck. They're just one of many "personalized pricing" companies that have attracted investor capital to figure out how to charge you more for the things you need, or merely for the small pleasures of life.

Personalized pricing (that is, "surveillance pricing") is part of the "pricing revolution" that is underway in the US and the world today. Another major element of this revolution are the "price clearinghouses" that charge firms within a sector to submit their prices to them, then "offer advice" on the optimum pricing. This advice – given to all the suppliers of a good or service – inevitably boils down to "everyone should raise their prices in unison." So long as everyone follows that advice, we poor suckers have nowhere else to go to get a better deal.

This is a pretty thin pretext. Price-fixing is illegal, after all. These companies pretend that when all the meat-packers in America send their pricing data to a "neutral" body like Agri-Stats, which then tells them all to jack up the price of meat, that this isn't a price-fixing conspiracy, since the actual conspiracy takes the form of strongly worded suggestions from an entity that isn't formally part of the industry:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/04/dont-let-your-meat-loaf/#meaty-beaty-big-and-bouncy

Same goes for when all the landlords in town send their rental data to a company like Realpage, which then offers "advice" about the optimum price, along with stern warnings not to rent below that price: apparently that's not price-fixing either:

https://popular.info/p/feds-raid-corporate-landlord-escalating

It's not just sellers who engage in this kind of price-fixing – it's also buyers. Specifically buyers of labor, AKA "bosses." Take contract nursing, where a cartel of three staffing apps have displaced the many small regional staffing agencies that historically served the sector. These companies buy nurses' credit history from the unregulated, Wild West data-brokerage sector. They're checking to see whether a nurse who's looking for a shift has a lot of credit-card debt, especially delinquent debt, because these nurses are facing economic hardship and will accept a lower wage than their better-off compatriots:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/12/18/loose-flapping-ends/#luigi-has-a-point

This is surveillance pricing for buyers, and as with the sell-side pricing revolution, buyers also make use of a third party as an accountability sink (a term coined by Dan Davies): the apps that they use to buy nursing labor are a convenient way for hospitals to pretend that they're not engaged in price-fixing for labor.

Veena Dubal calls this "algorithmic wage discrimination." Algorithmic wage discrimination doesn't need to use third-party surveillance data: Uber, who invented the tactic, use their own in-house data as a way to make inferences about drivers' desperation and thus their willingness to accept a lower wage. Drivers who are less picky about which rides they accept are treated as more desperate, and offered lower wages than their pickier colleagues:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/12/algorithmic-wage-discrimination/#fishers-of-men

But this gets much creepier and more powerful when combined with aggregated surveillance data. This is one of the real labor consequences of AI: not the hypothetical millions of people who will become technologically unemployed, numbers that AI bosses pull out of their asses and hand to dutiful stenographers in the tech press who help them extol the power of their products; but rather the millions of people whose wages are suppressed by algorithms that continuously recalculate how desperate a worker is apt to be and lower their wages accordingly.

This is as good a candidate for AI regulation as any, but it's also a very good reason to regulate data brokers, who operate with total impunity. Thankfully, Biden's Consumer Finance Protection Bureau passed a rule that made data brokers effectively illegal:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/10/getting-things-done/#deliverism

But then Trump got elected and his despicable minions killed that rule, giving data brokers carte blanche to spy on you and sell your data, effectively without restriction:

https://www.wired.com/story/cfpb-quietly-kills-rule-to-shield-americans-from-data-brokers/

(womp-womp)

Also, Biden's FTC was in the middle of an antitrust investigation into surveillance pricing on the eve of the election, a prelude to banning the practice in America:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/07/24/gouging-the-all-seeing-eye/#i-spy

But then Trump got elected and his despicable minions killed that investigation and instead created a snitch line where FTC employees could complain about colleagues who were "woke":

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/bedoya-statement-emergency-motion.pdf

(Womp.)

(Womp.)

Naomi Klein's Doppelganger proposes a "mirror world" that the fever-swamp right lives in – a world where concern for children takes the form of Pizzagate conspiracies, while ignoring the starving babies in Gaza and the kids whose parents are being kidnapped by ICE:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/05/not-that-naomi/#if-the-naomi-be-klein-youre-doing-just-fine

The pricing revolution is a kind of mirror-world Marxism, grounded in "From each according to their ability to pay; to each according to their economic desperation":

https://pluralistic.net/2025/01/11/socialism-for-the-wealthy/#rugged-individualism-for-the-poor

A recent episode of the excellent Organized Money podcast featured an interview with Lee Hepner, an antitrust lawyer who is on the front lines of the pricing revolution (on the side of workers and buyers) (not bosses):

https://www.organizedmoney.fm/p/the-wild-world-of-surveillance-pricing

Hepner is the one who proposed the formulation that personalized pricing is a way for corporations to decide that your dollars are worth less than your neighbors' dollars – a form of economic discrimination that treats the poorest, most desperate, and most precarious among us as the people who should pay the most, because we are the people whose dollars are worth the least.

Now, this isn't always true. Earlier this month, Delta, United and American were caught charging more for single travelers than they charged pairs of groups:

https://thriftytraveler.com/news/airlines/airlines-charging-solo-travelers-higher-fares/

That's a way to charge business travelers extra – for valuing their dollars less than the dollars of families, not because business travelers are desperate, but because they are, on average, richer than holidaymakers (because their bosses are presumed to be buying their tickets). Sometimes, price discrimination really does charge richer people more to subsidize everyone else.

But here's the difference: when the news about the business-traveler's premium broke, its victims – powerful people with social capital and also regular capital – rose up in outrage, and the airlines reversed the policy:

https://thriftytraveler.com/news/airlines/delta-rethinks-higher-fares-solo-travelers/

If the airlines are still pursuing this kind of price discrimination, they'll do something sneakier, like buying our credit histories before showing us a price. This is something British Airways is already teeing up, by offering essentially zero reward miles to frequent travelers for partner airline tickets unless they're purchased from BA's own website:

https://onemileatatime.com/news/the-british-airways-club/

But BA operates in the UK, where most of the pre-Brexit, EU-based privacy regime is still intact, despite the best efforts of Keir Starmer to destroy it, something that neither Boris Johnson, nor Theresa May,nor Rishi Sunak, nor Liz Truss could manage:

https://www.openrightsgroup.org/press-releases/uk-privacy-erosion-sparks-eu-civil-society-call-to-review-adequacy-data-deal/

So for now, BA travelers might be safe from surveillance pricing, at least in the UK and EU. And that's the thing, America is pretty much cooked. It might be generations – centuries – before the USA emerges from its Trumpian decline and becomes a civilized democracy again. Americans have little hope of a future in which their government protects them from corporate predators, rather than serving them up on a toothpick, along with a little cocktail napkin.

The future of the fight against corporate power and oligarchy is something for the rest of the world to carry on, as the American hermit kingdom sinks into ever-deeper collapse:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/06/21/billionaires-eh/#galen-weston-is-a-rat

And as it happens, Canada's Competition Bureau, newly equipped with muscular enforcement powers thanks to a 2024 law, is seeking public comment on surveillance pricing and whether Canada should do something about it:

https://www.canada.ca/en/competition-bureau/news/2025/06/competition-bureau-seeks-feedback-on-algorithmic-pricing-and-competition.html

I'm writing comments for this one. If you're in Canada, or a Canadian abroad (like me), perhaps you could, too. If you're looking for an excellent Canadian perspective to crib from, check out this episode of The Globe and Mail's Lately podcast on the subject:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/podcasts/lately/article-the-end-of-the-fixed-price/

Just because America jumped off the Empire State Building, that's no reason for Canada to jump off the CN Tower, after all.

(Eh?)

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/06/24/price-discrimination/#algorithmic-pricing

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surveillance is inequality’s stabilizer

I'm in the home stretch of my 24-city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in LONDON NEXT TUESDAY (July 1) with TRASHFUTURE'S RILEY QUINN and then a big finish in MANCHESTER on July 2.

The "dictator's dilemma" pits a dictator's desire to create social stability by censoring public communications in order to prevent the spread of anti-regime messages with the dictator's need to know whether powerful elites are becoming restless and plotting a coup:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/26/dictators-dilemma/#garbage-in-garbage-out-garbage-back-in

Closely related to the dictator's dilemma is "authoritarian blindness," where an autocrat's censorship regime keeps them from finding out about important, socially destabilizing facts on the ground, like whether a corrupt local official is comporting themself so badly that the people are ready to take to the streets:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/02/24/pluralist-your-daily-link-dose-24-feb-2020/#thatswhatxisaid

The modern Chinese state has done more to skillfully navigate the twin hazards of the dictator's dilemma and authoritarian blindness than any other regime in history. Take Xi Jinping's 2012-2015 anticorruption purge, which helped him secure another ten year term as Party Secretary. Xi targeted legitimately corrupt officials in this this sweeping purge, but – crucially – he only targeted corrupt officials in the power-base of his rivals for Party leader, while leaving corrupt officials in his own power base unscathed:

https://web.archive.org/web/20181222163946/https://peterlorentzen.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Lorentzen-Lu-Crackdown-Nov-2018-Posted-Version.pdf

How did Xi accomplish this feat? Through intense, fine-grained surveillance, another area in which modern China excels. Chinese online surveillance is often paired with censorship, both petty (banning Winnie the Pooh, whom Xi is often mocked for resembling) and substantial (getting Apple to modify Airdrop for every user in the world in order to prevent the spread of anti-regime messages before a key Party leadership contest).

But there are a lot of instances where China spies on its people but doesn't censor them, even if they are expressing dissatisfaction with the government. Chinese censors allow a surprising amount of complaint about official incompetence, overreach and corruption, but they completely suppress any calls for mobilization to address these complaints. You can be as angry as you want with the government online, but you can't call for protests to do something about it:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1251722

This makes perfect sense in the context of "authoritarian blindness": by allowing online complaint, an autocrat can locate the hot-spots where things are reaching a boiling-over point, and by blocking public manifestations, the autocrat can prevent the public from turning their failings into a flashpoint that endangers the autocracy.

In other words, autocrats can reserve to themselves the power to decide how to defuse public anger: they can suppress it, using surveillance data about the people who led the online debate about official failures to figure out who to intimidate, arrest, or disappear. Or they can address it through measures like firing corrupt local officials or funding local social programs (toxic waste cleanups, smokestack regulation, building schools and hospitals, etc) that make people feel better about their government.

Autocracy is an inherently unstable social situation. No society can deliver everything that everyone in it desires: if you tear down existing low-density housing and build apartment blocks to decrease a housing shortage, you'll delight people who are un- or under-housed, and you'll infuriate people who are happily housed under the status quo. In every society, there's always someone getting their way at the expense of someone else.

Obviously, widespread unhappiness is inherently socially destabilizing. After all, no society can police every action of every person. From littering to parking in disabled parking spots, from paying your taxes to washing your hands before serving food, a society relies primarily on people following the rules without even though their face little to no risk of being punished for breaking them. The easiest way to get people to follow the rules is to foster a sense of the rules' legitimacy: people may not agree with or understand the rationale for a rule, but if they view the process by which the rule was decided on as a legitimate one, then they may follow it anyway.

This legitimacy is a source of social stability. Sure, your candidate might lose the election, or the government might enact a policy you hate, but if you think the election was fair and you believe that you can change the policy through democratic means, then you will be on the side of preserving the system, rather than overturning it.

A democracy's claim to legitimacy lies in its popular mandate: "Sure, I don't like this decision, but it was fairly made." By contrast, a dictator's legitimacy comes their claims to wisdom: "Sure, I don't like this decision, but the Supreme Generalissimo is the smartest man in history, and he says it was the right call."

You can see how this is a brittle arrangement, even if the dictator is a skilled autocrat who makes generally great decisions: even a great decision is going to have winners and losers, and it might be hard to convince the losers that they keep losing because they deserve to lose. And that's the best outcome, where an autocrat is right. But what about when the autocrat is wrong? What about when the autocrat makes a bunch of decisions that make nearly everyone consistently worse off, either because the autocrat is a fool, or because they are greedy and are stealing everything that isn't nailed down?

Every society needs stabilizers, but autocracies need more stabilizers than democracies, because the story about why you, personally, are getting screwed is a lot less convincing in an autocracy ("The autocrat is right and you are wrong, suck it up") than it is in a democracy ("This was the fairest compromise possible, and if it wasn't, we need to elect someone new so it changes").

The Snowden revelations taught us that there is no distinction between commercial surveillance and government surveillance. Governments spy, sure, but the most effective way for governments to spy on us is by raiding the data troves assembled by technology companies (for one thing, these troves are assembled at our own expense – we foot the bill for this spying whenever we send money to a phone or tech company). The tech companies were willing participants in this process: the original Snowden leak, about the "PRISM" program, showed how tech companies made millions of dollars by siphoning off user data to the NSA on demand:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PRISM

It was only later that we learned about another NSA program, "Upstream," through which the NSA was wiretapping the tech companies' data-centers, acquiring all of their user data, and then requesting the data that interested them through PRISM, as a form of "parallel construction," which is when an agency learns a fact through a secret system, and then uses a less-secret system to acquire the same fact, in order to maintain the secrecy of the first system:

https://www.eff.org/pages/upstream-prism

Upstream really pissed off the tech companies. After all, they'd been dutifully rolling over and handing out their users' data in violation of US law, risking their businesses to help the NSA do mass spying, and the NSA paid them back by secretly spying on the tech companies themselves! That's a hell of a way to say thank you to your co-conspirators. After Upstream, the tech companies finally started encrypting the links between their data-centers, which made Upstream-style collection infinitely harder:

https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2013/11/yahoo-will-encrypt-between-data-centers-use-ssl-for-all-sites/

But that hardly ended the mass surveillance private-public partnership. Congress continued to do nothing about privacy (the last federal consumer privacy law Congress gave Americans is 1988's Video Privacy Protection Act, which bans video store clerks from telling newspapers about the VHS cassettes you take home) (we used to be a country). That meant that tech companies could collect our data will-ye or nil-ye, and that data brokers could buy and sell that data without any oversight or limitation:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/02/20/privacy-first-second-third/#malvertising

There's many reasons that Congress failed to act on privacy. Obviously, they face immense pressure from lobbyists for the commercial surveillance industry – but they also face covert and powerful pressure from public safety agencies, cops, and spies, who rely on private sector data as a source of off-the-books, warrantless, ubiquitous surveillance.

Why does America need so much spying? Well, because America has always been imperfectly democratic, from its inception as a enslaving nation where millions of people were denied both the ballot and personhood; and as a patriarchal nation where half of the remaining people were also denied the franchise; and as a colonialist nation where an entire culture of people had been subject to genocide, land theft, and systematic oppression. This is an obviously unstable arrangement. Whether in chains, on a reservation, or under the thumb of a husband or father, there were plenty of Americans who had no reason to buy into the system, accept its legitimacy, or follow its rules. To keep the system intact, it wasn't enough to terrorize these populations – America's rulers had to know where to inflict terror, which is to say, where order was closest to collapsing.

Some of America's first spies were private sector union-busters, the Pinkerton agency, who served as a private spy army for bosses who wanted to find the leverage points in the worker uprisings that swept the country. The Pinkertons' pitch was that it was cheaper to pay them to figure out who the most important union leaders were and target them for violence, kidnapping, and killing than it was to give all your workers a raise.

This is an important aspect of the surveillance project. Spying is part of a broader class of activities called "guard labor" – anything you might pay someone to do that results in fewer guillotines being built on your lawn. Guard labor can be paying someone to build a wall around your estate or neighborhood. It can be paying security guards to patrol the wall. It can be paying for CCTV operators, or drone operators. It can be paying for surveillance, too.

Guard labor isn't free. The pitch for guard labor is that it is a cheaper way to get social stability than the alternative: building schools and hospitals, paying a living wage, lowering prices, etc. It follows that when you make guard labor cheaper, you can build fewer schools and hospitals, pay lower wages, and raise prices more, and buy more guard labor to counter the destabilizing effect of these policies, and still come out ahead.

American politics have been growing ever more unstable since the 1970s, when oil crisis gave way to the Reagan revolution and its raft of pro-oligarch, anti-human policies. Since then, we've seen an unbroken trend to wage stagnation and widening inequality. As a new American oligarch class emerged, they gained near-total control over the levers of power. In a now-famous 2014 paper, political scientists reviewed 1,779 policy fights and found that the only time these cashed out in a way that reflected popular will is when elites favored them, too. When elites objected to something, it literally didn't matter how popular it was with everyone else, it just didn't happen:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/testing-theories-of-american-politics-elites-interest-groups-and-average-citizens/62327F513959D0A304D4893B382B992B

It's pretty hard to make the case that the system is legitimate when it only does things that rich people want, and never does things the vast majority of people want when these conflict with rich peoples' desires. Some of these outcomes are merely disgusting and immoral, like abetting genocide in Gaza, but more frequently, the policies elites favor are ones that make the rich richer: climate inaction, blocking Medicare for All, smashing unions, dismantling anti-corruption and campaign finance laws.

I don't think it's a coincidence that America's democracy has become significantly less democratic at the same time that mass surveillance has grown. Mass surveillance makes guard labor much cheaper, which means that the rich can make their lives better at all of our expense and still afford the amount of guard labor it takes to keep the guillotines at bay.

Cheap guard labor also allows the rich to strike devil's bargains that would otherwise be instantaneously destabilizing. For example, the second Trump election required an alliance between the tiny minority of ultra-rich with the much larger minority of virulent racists who were promised the realization of their psychotic fantasy of masked, armed goons snatching brown people off the streets and sending them to offshore slave labor camps. That alliance might be a good way to elect a president who'll dismantle anticorruption law and slash taxes, but it won't do you much good if the resulting ethnic cleansing terror provokes a popular uprising. But what if ICE can rely on Predator drones and cell-site simulators to track the identities of everyone who comes out to a protest:

https://www.wired.com/story/cbp-predator-drone-flights-la-protests/

What if ICE can buy off-the-shelf facial recognition tools and use them to identify people who are brave enough to step between snatch-squads and their neighbors?

https://www.404media.co/ice-is-using-a-new-facial-recognition-app-to-identify-people-leaked-emails-show/?ref=daily-stories-newsletter

Each advance in surveillance tech makes worse forms of oppression, misgovernance and corruption possible, by making it cheaper to counter the destabilizing effect of destroying the lives of the populace, through identifying the bravest, angriest, and most effective opposition figures so they can be targeted for harassment, violence, arrest, or kidnapping.

America's private sector surveillance industry has always served as a means of identifying and punishing people who fought for a better country. The first credit reporting bureau was the Retail Credit Company, which used a network of spies and paid informants to identify "race mixers," queers, union organizers and leftists so that banks could deny them credit, landlords could deny them housing, and employers could deny them jobs:

https://jacobin.com/2017/09/equifax-retail-credit-company-discrimination-loans/

Retail Credit continued to do this until 1975, when, finally, popular opinion turned against the company, so it changed its name…

…to Equifax.

Today, Equifax is joined by a whole industry of elite enforcers who use spying, legal harassments, mercenaries and troll armies to offset the socially destabilizing effects of the wealthy's misrule:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/23/launderers-enforcers-bagmen/#procurers

But despite centuries of American mass surveillance, America's oligarchs keep finding themselves in the midst of great existential crises. That's because guard labor – even surveillance-supercharged guard labor – is no substitute for policies that make the country better off. Oligarchs may want to tend the nation like a shepherd tends its flock, leaving enough lambs around to grow next year's wool. But they're all competing with one another, and they understand that the sheep they spare will like as not end up on a rival's dinner table. Under those circumstances, every oligarch ends up in a race to see who can turn us into lambchops first.

This is the dictator's dilemma, American style. The rich always overestimate how much social stability their guard labor has bought them, and they're easy mark for any creepy, malodorous troll with a barn full of machine-gun equipped drones:

https://twitter.com/postoctobrist/status/1909853731559973094

They accumulate mounting democratic debts, as destabilizing rage builds in the public, erupting in the Civil War, in the summer of 68, in the Battle of Seattle, in the Rodney King uprising, in the George Floyd protests, in Los Angeles rebellion. They think they can spy their way into a country where they have everything and we have nothing, and we like it (or at least, never dare complain about it).

They're wrong.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/06/26/autostabilizer/#slicey-bois

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

263 notes

·

View notes

Note

The study doesn't describe Keto or any low carb diet.

Their so called Low Carb diet is in reality a mixed diet in which calories from carbs and fat are roughly equal which is extremely harmful for biochemical reasons:

Carbohydrates: 214 (856, 39%) Protein: 103 (412), Fat: 105 (945)

Low carb diets are based on principle of not mixing fuel and have less than 26% of calories from carbohydrates.

Keto diets have like 10x lower consumption of carbohydrates.

*diet discussion tw* is there any long term research on the actual effects of the keto diet for people without epilepsy? my acquaintance keeps trying to pressure me into it because she claims it makes her more energetic (i have chronic fatigue) and when i say no bc the vast majority of humans need carbs to live healthily, she asks for "evidence" 🙄 thanks for any help!

I mean, first of all the quality of evidence supporting the Keto diet to treat epilepsy is “low to very low” according to one of the most trusted sources for medical evidence review.

As for the rest of us:

This study prospectively examined the relationship between low carbohydrate diets, all-cause death, and deaths from coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (including stroke), and cancer in a nationally representative sample of 24,825 participants of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) during 1999 to 2010. Compared to participants with the highest carbohydrate consumption, those with the lowest intake had a 32% higher risk of all-cause death over an average 6.4-year follow-up. In addition, risks of death from coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and cancer were increased by 51%, 50%, and 35%, respectively.

The results were confirmed in a meta-analysis of seven prospective cohort studies with 447,506 participants and an average follow-up 15.6 years, which found 15%, 13%, and 8% increased risks in total, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality with low (compared to high) carbohydrate diets.

[media summary] [scientific article]

So basically, these kind of diets increase your risk of literal death.

In the words of the researchers: “These diets are unsafe and they should be avoided.”

465 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contrary to popular perception, the Gestapo was actually a relatively small organization with limited surveillance capability; still it proved extremely effective due to the willingness of ordinary Germans to report on fellow citizens.

even evil cannot govern without the consent of the people, the bastards

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm skeptical of the "chatgpt causes brain damage" thing going around but I suspect there's probably a rational kernel of truth in the... idk intellectual helplessness it fosters and is explicitly designed to foster as a product. which isn't unique to llms by any means

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If it's amazing, they'll know."

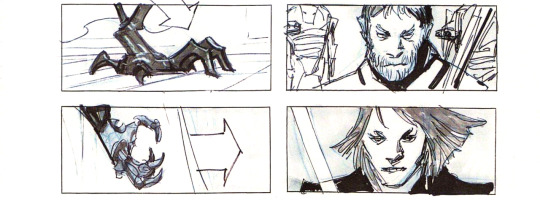

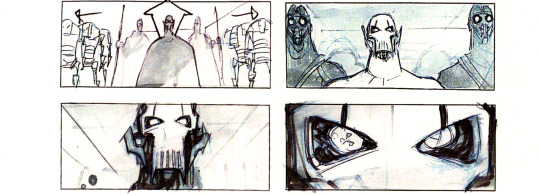

When talking about "George Lucas' vision" and the original six Star Wars films, there's one thing to bear in mind and that's Lucas' style of filmmaking.

These are movies for kids, designed to emulate the Saturday matinee serial format from the '30s, à la Flash Gordon. You see this most of all in the dialog. But something else you notice is George Lucas' filmmaking style, particularly in how he films and edits.

Take Darth Vader's introduction, for example.

Look at the composition: Vader stands tall, in contrast to the - as the script puts it - "fascist white armored suits of the Imperial stormtroopers". They're all in white, he's all in black, he's bigger badder, emerging from a cloud of smoke. What an entrance.

But if you think about it, it's just a single full shot. Very basic.

Compare this to Kenobi, wherein Vader is treated like a monster out of a horror movie. First, you glimpse his shadow, people reacting...

... then ominous bits and pieces like his boots or his lightsaber...

... and finally Vader himself, in all his terrifying glory.

That's a modern way of shooting it and it admittedly makes ol' Darth seem that much more imposing and absolutely badass.

But Lucas comes from a background of editing, experimental filmmaking and used to work as a documentary cameraman.

So what he did is just put the camera down and have Vader walk in. It's a faster yet differently-efficient way to introduce the character. It's more about dynamic pacing and visuals.

And that is Lucas' style. In his words:

"The way these films were put together, they're shot very much like a documentary film and the action of stage, and then I shoot around it. I don't stage for the camera. And as a result, there are a lot of things that happen pretty much by accident. It lends an aura of authenticity to everything." - Star Wars - Episode I: Podracing Featurette, 1999

Another example: the introduction of General Grievous.

A door opens revealing his ugly mug and he walks in. Boom.

But in Star Wars Storyboards: The Prequel Trilogy, you find that - as envisioned by the storyboard artists - our introduction to Grievous would've been very different.

"We wanted to have the introduction to Grievous be a series of really close shots that would be a series of details: his creepy foot, his creepy hand...

... his scary alien eyes...

... but George brought up an interesting point. He didn't want the film to concentrate on one design detail or one element— but rather let the world be there and let the viewer find those things without necessarily having it shoved in their face." - Derek Thompson, SW Storyboards: The Prequel Trilogy, 2013

"George nixed the idea, saying: 'I don't want something to be special because of how it's filmed, but because of what it is. Just put the camera on it and let it play out in front of the audience. If it's amazing, they'll know.'" - Iain McCaig, SW Storyboards: The Prequel Trilogy, 2013

That's it in a nutshell. "If it's amazing, they'll know."

The above storyboards look awesome and seeing Grievous be introduced that way would be great... but it wouldn't be Lucas' Star Wars. It would be some other director taking a crack at it.

And this way of shooting can be weird, even boring, at times. I mean compare Mace leading his troops into battle...

... to Aragorn leading his, in Return of the King.

The latter is so much more emotionally impactful. For a number of reasons (eg: Aragorn is a deuteragonist, Mace is a secondary character with less development), but one of them is that the moment is just shot in a way that's more interesting.

First we have an angle on Aragorn as he smiles and charges. Then the rest of the other characters as they react and follow suit, then the troops do the same.

With Mace it's, uh, *checks notes* he flourishes his saber and charges, the clones follow. Hell, for half a second we're looking at just an empty screen.

But y'know what the shot does look like?

It looks like something out of a WW1 documentary.

It's that authenticity he was mentioning further up.

At the end of the day, you can call it campy or bad... it's Lucas' style. It's cinema. There's a logic to it.

"To me, the script is just a sketchbook, just a list of notes, and, sometimes, I prefer the documentary feel of free flow, so I let my instincts tell me where to go. I like to create cinematically; I don't like to have a plan. I like to have a rough idea of what I'm going to do-certain themes, certain issues I'm going to deal with-and then I try to do so." - The Making of Revenge of The Sith, page 116, 2005

He doesn't try to make a character look particularly badass with camera angles or make the shot too choreographed, he just goes with the flow, and makes the deliberate choice to shoot it that way, because for better or for worse... it's his movie.

So yeah, just a tidbit I thought would be interesting.

Edit:

@schilkeman added this very interesting point in the replies:

"He doesn’t stage for the camera, but he does compose for the camera. The documentary style, while somewhat detached, requires the filling of the screen with motion and light. The way things move through frame seem very important to him. These are things his films excel at."

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

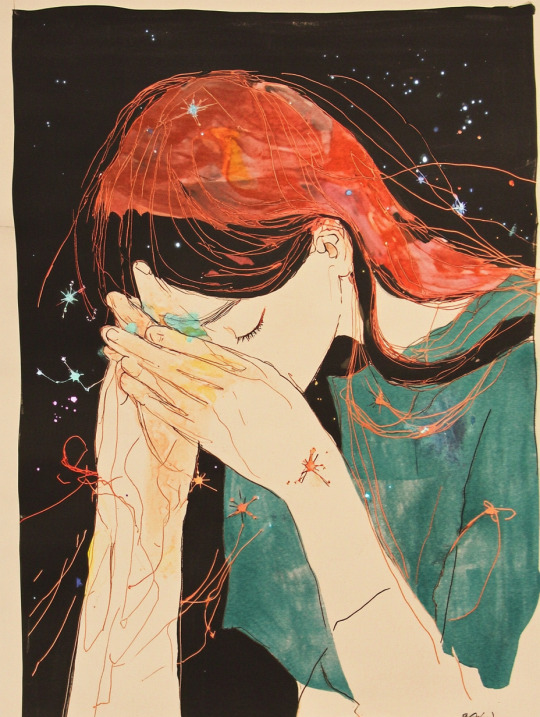

search inside yourself and find the outmost reaches of the universe

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

That's nonsense. Most of people don't have this kind of memory for enormous amounts of detailed information.

Like was OP homeschooled and never met people, or what?

I’m shocked at how many people are reacting to the Tucker-Cruz interview by saying that asking “what is the population of Iran?” is some kind of meaningless trivia question that it shouldn’t be seen as embarrassing for Cruz to not know.

For fuck’s sake. Every adult citizen of a democratic society should be expected to know a ballpark estimate of how many people live in most of the world’s countries. At least within an order of magnitude.

If hearing an incorrect statement like “Barbados has a population of 45 million people” or “Indonesia has a population of 8.3 million people” doesn’t immediately strike you as wildly implausible, you are ignorant of the world in many fundamental ways and should be slightly embarrassed about that.

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

raginrayguns said: gmail was so much better than the competition in 2004

yes it was, but everything Google did was so much better than the competition in 2004!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

New pandemic in making.

Mamãe por que você dá comida pros passarinhos só de noite?

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually I have a post I want to make about Property Value.

Which is a topic that comes up a lot in discussions of rich people hoarding wealth, in NIMBY panics, and in the ever-increasing prices of homes. But I don't think we talk much about how the perniciousness of property value goes deeper and basically holds middle class people who own a home hostage.

So the set some context here: in 2025 the median US home sold for $416,000. Say you have a working class family who can't meet median, but who scraped and saved and penny-pinched their way to a $300,000 home.

Typically, when buying a first home, you pay 20% down directly, and take 80% out as a mortgage from the bank. For this family, that means $60,000 of their liquid money (and let's say it took them 10-15 years to save that amount), and a $240,000 loan from the bank.

That's $240,000 in debt the family is. Which will be repaid over 30 years, with interest, at a rate that usually means for the lifetime of the loan, they end up paying back double the original loan.

However this massive $240,000 debt is generally considered "okay" debt to have, because it's backed by the house. If things go truly sour, the bank can take the house (and what's a little homelessness between friends).

That $60,000 the family put down is considered equity, and equity is money you "have", but isn't accessible.

Scenario: Now let's say something happens. Someone in the family loses their job, and the only job they can find requires moving. Or a family member across the country can't care for themselves anymore and so this family needs to move to be closer to them. The family gets divorced. Someone in the family is allergic to material in the home. Someone in the family is being stalked or abused and needs to leave the town. Anything at all, which would require selling the home and moving.

Case 1: The family is able to sell it for exactly what they paid (same property value, no increase or decrease). You would think the math is clean. They are paid $300,000 for the house. $240,000 repays the bank loan. The remaining $60,000 of equity goes right back to them. And they can use it (which took 10+ years to save up) to move across the country and buy a different $300,000 house.

Except no, it does not work like that.

The seller of a home is on the hook to pay commission to their realtor and the buyer's realtor. This is usually ~6% of the home value. They have to pay legal costs. There are taxes. There are miscellaneous costs. It can easily be 6-9% of the selling price of the house.

The bank NEEDS its $240,000 back. So those costs come from the equity. This family is not getting their $60,000 back. They're getting $30,000-$45,000, and now no longer enough money for a downpayment in their move. They're back to renting. Back to penny pinching. They can get by, but homeownership is now out of their grasp once more. Maybe in another 5 years, they'll have enough (unless home prices have increased too much by then) then they'll maybe never be homeowners again.

Case 2: The property value has DECREASED... Family is only getting offers in the $260,000 range.

If the family accepts a $260,000 sale, well $240,000 goes to the bank. This is genuinely non-negotiable. And that leaves.... maybe not enough money to even close on the house. Not enough to pay the realtors and the fees.

That $60,000 is wiped out, and the family is incapable of moving. Never mind losing 10+ years of savings--they're below $0. They don't have the money to close. It's financially impossible to sell. They are stuck with the mortgage. They are stuck with the house. (Maybe they'll rent it, if they can. And now they're landlords by circumstance, which is often NOT profitable when you're not a trust fund baby renting out a totally-paid-for no-mortgage home.) But whatever the case, they cannot sell it. And if the reason for selling was a job loss... well, they can be homeless soon. And if the property value dropped below $240,000, they can be homeless AND owe a bank debt. A $60,000 nest egg wiped completely out, with a bank debt owed on top of that.

So how do people avoid financial destitution when moving?

The most sensible answer is building up equity by paying down the loan--but it's important to know that mortgages are super interest heavy in the early life of the loan. With a 5% interest rate (BETTER, btw, than current rates) this family would be paying $15,460 the first year, and only $3,540.88 is actually chipping at that $240,000 principle. The other $11,919.59 was pure interest to the bank.

So after 1 year, the family went from having $60,000 equity in the house to $63,540.88 equity in the house. This buys a little extra wiggle room when juggling closing costs. But not very much. Even after 3 years, the family has just a little over $70,000 of equity, and just under $230,000 still left on the loan. So if the family has to move for any reason (sickness! death! job loss!) in those 3 years, it's probably financially devastating.

But there is a second answer to avoiding financial ruin: and that is Property Value going up.

Any amount of property value increase is PURE equity. The bank only cares about the amount of money is gave you. If after 3 years, that house is now worth (and can sell for) $315,000 (which is appreciation of only 1.6% a year. Most home appreciation is closer to 3%), that's more equity increase than they got from 36 diligent months of mortgage payment.

If they can sell for $315,000, pay $230,000 of that to the bank, that leaves $85,000. $25,000 goes to paying the realtors and the closing costs and.... the family is back to their $60,000 downpayment. Not trapped. Able to sell. Able to buy a new $300,000 home in the place they moved. Able to just maintain homeownership status.

But wait, if their home appreciated to $315,000, didn't all the other homes do the same, so now $60,000 isn't enough

Smart eye, lad! You've identified why this is a TERRIBLE rat race for the people scraping money together to live, and is ONLY a profitable leisure activity for rich people who sell homes like collectables.

Now because the increase is pure equity, a similar family with decent property value increase can funnel that extra equity into affording to meet the new higher down payment (remember the downpayment is only 20%, so even if the new place is similarly higher in property value, you only need to match that increase 20% for the downpayment). Which gets their foot in the door. But now their new mortgage is higher than the old one. More expensive. More interest.

But there is a losing scenario here--if home property values increased everywhere else, but not where you live. Then this family is back to surrendering homeownership. Because even if they can sell their place, they can't buy the next home.

It forces them to care about their own Property Value increase because, if it doesn't increase while everywhere else does, it traps them.

So what do I mean by all this

If the value of all homes dropped 50% overnight, I assume most people here would celebrate. Affordable homes! Rich people upset and crying! So much to love.

But in reality, that 50% drop would likely continue to mean no home for most of us, because the people who could sell you the homes would be financially incapable.

For the family above with the $240,000 mortgage, that mortgage does not reach halfway-paid-off until year 20 of the 30 year mortgage (remember the interest frontloading). If a family still owes $230,000 in bank loans on a place that can only sell for $150,000, they can't sell it to you. That house is the bank's collateral securing the loan. Their mortgage is underwater. They're trapped. They cannot sell it. You cannot have it.

Something similar happened in the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, and the only people who got out okay were ones who could stay the course, keep making the mortgage payments, and wait it out long enough for property value to recover.

Those who couldn't got foreclosed on. Those who couldn't were left in financial devastation.

So in conclusion?

Banks profit off of mortgages. Rich people profit off of hoarding housing stock and selling it as the property value increases. Real estate companies profit off of home sales. And the regular people, who managed to achieve home ownership, are shackled to the price-go-up system to avoid financial ruin. They're forced to care about their property value because it is the singular determinant of whether they're trapped in place, whether they'll be okay if they lose their job, whether they could move due to an important life event.

It's a profit system for the rich where the cogs are middle class people who could achieve homeownership, running a machine where every single crank locks the poorer and younger generations out of home ownership forever.

4K notes

·

View notes