Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

I created this image macro using the distracted boyfriend meme format. The meme simply, and obviously, gets at themes of distraction and disloyalty. Popular adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels often play up the marriage plots, simplify them, and ignore most (or any) of Austen’s irony.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

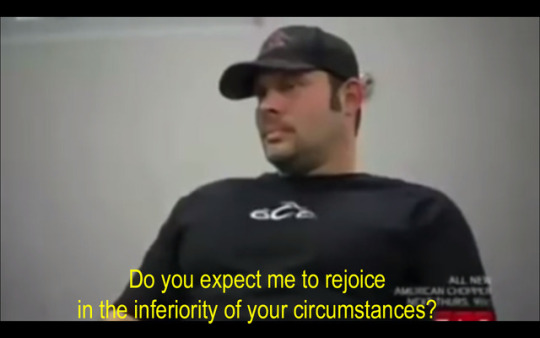

The American Chopper meme became popular this past March, 2018. Vox wrote an article explaining its significance and the ways in which it should be read. In simplistic terms, this meme is about constructing the dramatics of an argument in which both sides are shown through a fair lens.

This specific version of the meme uses dialogue from Darcy’s first proposal to Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice (the lines are from the 2005 film adaption starring Kiera Knightley). Overlaying the dialogue between Elizabeth and Darcy shows a successful execution of this meme. Austenites viewing this meme would understand that both sides of the argument should be viewed sympathetically.

The American Chopper/Pride and Prejudice meme mashup thus offers a better reading of both memes when understood fully.

Pride and Prejudice // 2005

47K notes

·

View notes

Link

It may feel uncomfortable to think of #metoo as a meme, but recall the definition of meme as “a unit of cultural transmission,” and suddenly the label feels fair. The #metoo movement was started by Tarana Burke in the late ‘90s to support victims and highlight the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault. Alissa Milano posted a tweet in October of 2017 asking women to respond with #metoo if they’d ever been sexually harassed or assaulted, and the hashtag took off.

In the following months, various articles surfaced which discussed the #metoo movement through Jane Austen. In this particular article Paula Marantz Cohen discussed Mr. Collins proposal to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. She discussed his tactless approach, and the truly complicated situation that Elizabeth Bennet was in. She discussed how Elizabeth’s refusal put herself, and her family, at risk. Cohen, however, notes Austen’s ability to control the narrative, recognize the wrong situation, and provide a more attractive option (re: Darcy). Cohen recognizes that these refusals are not always possible, but that we can look to this scene, and scenes like this, for ways in which they can be happening.

This article contributes both to the meme of Austen, as well as the #metoo meme. To the Austen meme, it adds to the idea of Austen as prototypical feminist. Readers who see this article, or articles like this, are likely to keep these feminist readings of Austen in mind if and when they return to Austen’s novels. To the #metoo meme, it offers gentle entry. Cohen is not calling for any radical movement or callout of everybody’s own Mr. Collins, she is calling for attempts to shut them down whenever it is safe and possible.

This article exists online in a stagnant, written, form, while #metoo as a movement continues to grow around it. The mimetic influence of this article is not stagnant: memes change through time and culture. As previously noted, the fluid or unpredictable nature of memes is especially relevant with internet memes. Just 13 days after this article was published, a new #metoo story was made public which received intense backlash. Babe.net posted a story about a date gone incredibly sour with actor/director Aziz Ansari, and The Atlantic published a response piece questioning its journalistic integrity, along with the integrity of women who had labeled this moment as a #metoo moment. The Atlantic article went so far as to negate the scene as “a whole country full of young women who don’t know how to call a cab”.

This interaction between ideas represented a shift in #metoo as a meme. It complicated the meme, even offered for a potential space for it to break into two separate memes--one championing a total recalibration of what is considered acceptable behavior when relating to another individual sexually, and one which championed a more conservative take on ending sexual harassment and assault.

In the wake of that shift in the #metoo meme, this article can be read in many different ways. These multiple readings exemplify the trouble with stagnant images or articles or books (such as any of Austen’s)--they are not always read in the mimetic context in which they were produced.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

When image macros are spread widely around the internet, they are referred to simply as memes. Internet memes are the same as regular memes, but specifically (and obviously) situated on the internet. They provide a vivid example of the ways in which fanfiction and memes overlap, ultimately creating memes which are more fit and adaptive.

On her personal blog KC Kahler dedicated multiple posts to displaying image macros which combined screenshots from Jane Austen film adaptations with headlines from popular satirical news outlet, The Onion.

Kahler’s image macro shown above does not expand far beyond Jane Austen’s pre-existing narrative world of Emma. It does, however, almost perfectly represent the two major conflicting themes present in Austen as a meme (which I discussed in my last post), the theme of marriage plot and the undeniable presence of sarcasm. This image macro actually helps me better understand how marriage plot and sarcasm co-exist so well. Of course Emma married Mr. Knightley in the end. Of course marriage is really about financial security.

An example of one of Kahler’s image macros which is especially fanfiction-esque, shows an image of Northanger Abbey’s Catherine Morland and Henry Tilney embracing, with The Onion headline “Reverend Blessed with 9-inch Penis”. Obviously, this is far more sexual than any content Jane Austen actually wrote about in Northanger Abbey (or any of her novels). This image macro thus functions as fanfiction by producing, or at least suggesting, a hidden plot line within the original narrative world: one in which Henry Tilney’s appeal was a generous (physical) endowment.

Image macros such as these, and internet memes in general, aid the survival of Austen as a meme more generally. People who were not pre-existing fans of Jane Austen are likely to stumble across some of these memes. They are not difficult to consume, and thus, Austen as meme is able to spread incredibly quickly. It is possible, also, that these memes will lead new people back to original works by Austen.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Austen, Mimetics, and Fanfiction (introduction to the blog)

Lately, I have been struck by the recurring thought that Jane Austen is treated unlike any other author. The many views of Janeites seem largely paradoxical at times. Jane Austen has been appropriated to communicate both alt right (https://www.chronicle.com/article/Alt-Right-Jane-Austen/239435) and liberal feminist (https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-jane-austen-can-teach-us-about-sexual-harassment-1514822957) ideals. She is heralded as mother of “chick lit” (Harmon, 201) and game theorist (https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/23/books/michael-chwe-author-sees-jane-austen-as-game-theorist.html).

The purpose of this blog is to examine Jane Austen’s own work, as well as her continued fandom, in relation to meme theory and fanfiction. If I can gain a better understanding of why and how ideas survive, than perhaps I can gain a better understanding of the cloud of truths which surround Austen. In this introductory post I will give a brief definition of meme theory and fanfiction, relate them to each other, and finally relate them back to Jane Austen, specifically her novels Northanger Abbey and Pride and Prejudice. Northanger Abbey because of its meta engagement with meme/fanfiction, and its general engagement with all things Austen (social class, marriage plot, sarcasm). Pride and Prejudice because it is arguably peak Austen fandom (who doesn’t swoon over Colin Firth’s Mr. Darcy?).

I’ll start with meme theory. Meme theory was first introduced by Richard Dawkins in his popular science book The Selfish Gene and it has continued to gain traction since. Dawkins presented meme theory to discuss culture in terms of genetics/Darwinism, and in doing so, he framed the possibility of a fit idea. Think back to whatever you’ve learned about Darwin in the past. Survival of the fittest. Dawkins explained meme “as a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” (Dawkins, 192). He even named memes to rhyme with genes. Dawkins explained that the part of an idea which make up a meme, is the thing about it which many individuals hold in common, as opposed to all of the disparate parts. When we think about the act of reading, we might think about reading different books in different languages, but generally, we all imagine the act of internally spelling out letters and words on a page which string together to create some larger meaning.

It must be noted, that considering culture in terms of Darwinism is a bit terrifying (Darwinism was used to justify racism, and colonialism generally, for a long time), and that shouldn’t be ignored (Dawkins does seem to ignore that fact, however). Thinking about the ways in which ideas are alive/act similarly to living organisms, however, doesn’t feel inherently harmful. So let us remember the ways in which dominant cultures can aid in the survival or death of particular memes as we go forward.

This brings me to fanfiction. Fanfiction are “stories produced by fans based on plot lines and characters from either a single source text or else a “canon” of works” (Thomas, 1). Fanfiction allow narrative worlds to be expanded upon (outside of the original text). When fanfiction meet internet platforms this expansion becomes basically limitless.

Fanfiction, in my opinion, are interesting to think about in relation to meme theory. They represent an expansion of ideas which are so obviously shaped by those who consume those same ideas. Fanfictions expand on the original meme, or multiple memes, which a book represents. In doing so fanfiction aids in the survival of the original meme(s). The more forms these memes are willing to take, the more people who interact with them, the more likely they are to be passed on. Simultaneously, fanfiction allow fans to play a role in potentially mutating the original meme. It makes sense that a meme (like genes!) would mutate over time to become better suited for their current environment. With fanfiction, these meme mutations can happen almost instantaneously. In What is Fanfiction and Why are People Saying Such Nice Things about it, Bronwen Thomas points out that “fan communities proudly boast about the influence they have on people’s engagements with the storyworlds about which they write”(10). Fanfiction, especially that which is written online, is not always created by the dominant culture, or even by the dominant fandom. Many platforms allow for different voices to contribute more equally. The interesting thing about Austen fandoms and fanfics, however, is that they “tend to be quite conservative and fiercely protective of the Austen legacy” (Thomas, 6).

So what is the central meme we can draw from or around Jane Austen? What is it that fans set out so fiercely to protect, even within their own fanfic? Let’s take a closer look at a couple of Austen’s novels to gain a better understanding of the stakes. Every Austen novel contains a marriage plot. Every Austen novel simultaneously contains a lot of wit and irony. It is not always certain how these two things interact, but their combination leave a lot of room for interpretation.

Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey functions through sarcasm and the marriage plot (as most of her novels do). Northanger Abbey, a kind of gothic fanfiction in its own right, ends with the marriage of Catherine and Mr. Tilney. Much of the novel’s tension resides in the uncertainty of romantic feelings between the two. A tension which moves the plot equally, however, is the central irony. Northanger Abbey begins, “no one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would have supposed her born to be an heroine”(Austen, 5). This beginning shows irony through a meta-awareness of format which continues throughout. Not long after this intro, the narrator openly defends novels, “I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom with novel writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding”(Austen, 22). In this, the narrator defends Catharine’s enjoyment of novels, while once again showing self-awareness of form.

Peak engagement with gothic fiction as a genre comes through at the points in which Catherine interacts with the Tilney’s own abbey. Catherine asks Henry Tilney if the abbey is “a fine old place, just like what one reads about” (Austen, 107), and Henry responds by explaining it as gothic, with “sliding panels and tapestry” (Austen, 107), “gloomy passages” (Austen, 108), and beds with “a funeral appearance” (Austen, 108). Although the abbey does not end up fitting these gothic descriptions, Catherine leans into every gothic mood which strikes her, eventually convincing herself that the General Tilney has murdered his late wife. By engaging with stereotypically gothic images and tone, Austen expands the world of gothic fiction in her own right. Northanger Abbey can thus be taken as a fanfiction, while the meme of gothic fiction is passed on.

Although similarly framed through irony, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is a more classic example of Austen as marriage plot meme. In Pride and Prejudice there are multiple proposal scenes, and the proposals themselves make up the major plot developments within the novel. The novel begins with the line, “it is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife” (Austen, 3). This line might be ridiculous, and obviously untrue, but it nevertheless alerts readers to the tensions to come. Elizabeth Bennet is proposed to three times, once by her cousin Mr. Collins, and twice by Mr. Darcy. Each proposal represents a peak in her character development. The first by Mr. Collin’s allows for her to the assert the separation of her own needs from her parents desires for her, the second proposal (first of Mr. Darcey’s) provides space for Elizabeth to begin questioning her own view and judgements of the world, while the third proposal finally ends with an engagement to Darcy. Without the proposals, Pride and Prejudice would be plotless. The irony of the first line does not negate this fact.

The role of irony and marriage plot together ultimately serve to complicate the larger meme of Jane Austen. In a way, irony allows for people to take the marriage plot as seriously as they want to. You can imagine Austen as lover of the institution, lover of marriage, or as institutional cynic; both are supported within the original texts. This makes the meme of Austen, although difficult to pin down, perhaps especially mimetically fit. Austen can continue to mean a lot of different things to different people, and the two major conflicting memes which exist within her novels, allow for these external conflicting views to align with her as a larger cultural symbol. Perhaps the extreme adaptability of Austen as a meme is why Austenites feel such a need to defend her. Memes are adaptable when they serve people or cultures as a whole. Austen’s ironic marriage plots give the people stories which help situate themselves to the paradox’s which surround them everyday.

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Northanger Abbey. New York: Norton & Company, 2004.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. New York: Norton & Company, 2001.

Cohen, Paula. What Jane Austen Can Teach Us About Sexual Harassment. The Wall Street Journal, 1 Jan. 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-jane-austen-can-teach-us-about-sexual-harassment-1514822957.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press, 1976.

Harmon, Claire. Jane’s Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World. New York: Picador, 2009.

Mirmohamadi, Kylie. The Digital Afterlives of Jane Austen: Janeites at the Keyboard. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Wright, Nicole. Alt Right Jane Austen. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 12 Mar. 2017, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Alt-Right-Jane-Austen/239435.

Schuessler, Jennifer. Game Theory: Jane Austen Had it First. The New York Times, 22 Apr. 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/23/books/michael-chwe-author-sees-jane-austen-as-game-theorist.html.

Thomas, Bromwen. “What is Fanfiction and Why Are People Saying Such Nice Things About it.” Storyworlds: A Journal of Narrative Studies, vol. 3, 2011, pp. 1-24.

#Jane Austen#Janeites#Meme theory#Mimetics#dawkins#northanger abbey#pride and prejudice#meme#literature#fanfiction

6 notes

·

View notes