Occasional BL Manga Reviews. Asks and messages are always open for your questions, concerns, and suggestions.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

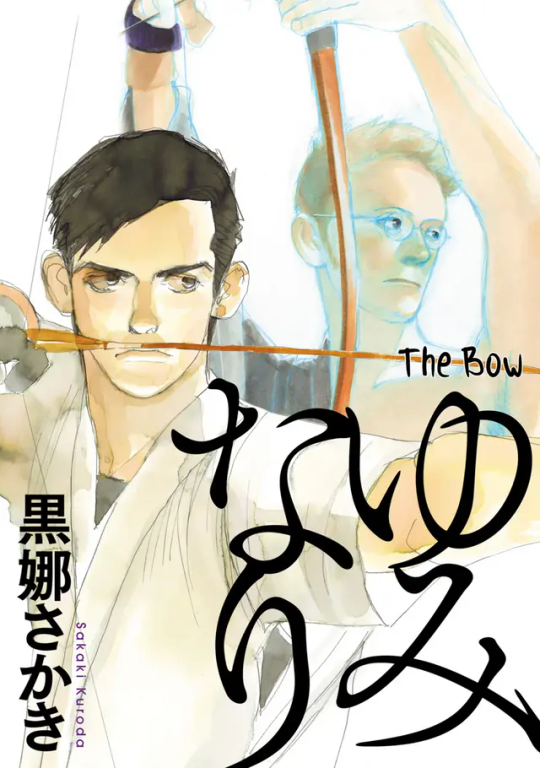

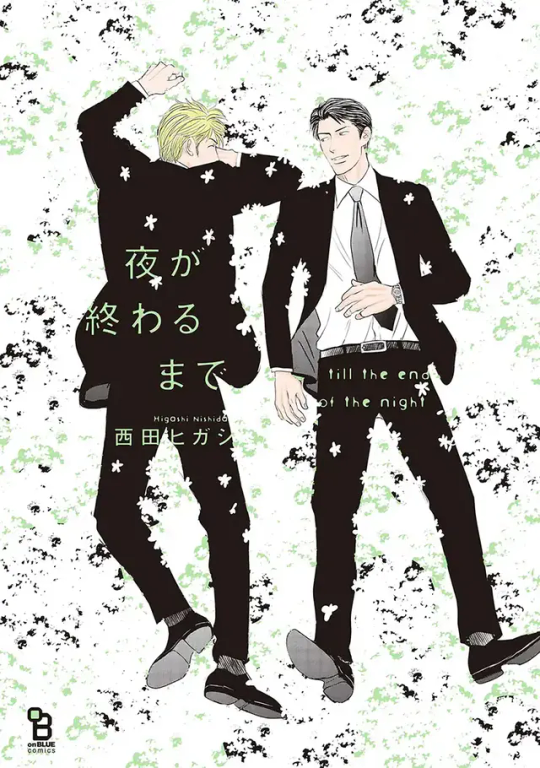

15/50: the loneliness of the forerunner ("the bow," "till the end of the night")

I read Evelyn Waugh's "Brideshead Revisited" at an impressionable time in my life (though I suppose if you are the kind of person to be moved by "Brideshead Revisited"—that is, a person prone to self-indulgent nostalgia—there is no safe time to read it) and thus live with the mark of being the kind of person who has committed to memory passages of a sentimental novel from the 1940s about a British man. Shameful! Let this be a lesson to you: the British will always find us when we are weak.

For those of you unfamiliar, "Brideshead Revisited" is about a rather ordinary middle class young man named Charles Ryder who at Oxford befriends Sebastian Flyte, the charismatic youngest son from a landed gentry family. Sebastian is tortured by a desire to escape the clutches of his family and eventually turns to a squalid life of alcoholism and poverty, much to Charles' confusion and vexation. Charles ends up romantically entangled with Sebastian's sister Julia, who in her own rebellion against her family has married a rather modern and horrible businessman named Rex Motram. In a striking passage during Charles and Julia's reunion, she asks Charles whether he loved Sebastian. "Oh yes," Charles says without hesitation. "He was the forerunner." It is a line that never leaves Julia's mind, and she brings it up later when she and Charles part, never to see each other again.

I am the same—I have never forgotten that line. Waugh did not write Charles and Sebastian explicitly as lovers, but he also did not shy away from the obvious romantic overtones of their friendship. Sebastian's father's mistress calls them out on it, commenting ironically on those too-close "romantic friendships." Charles (in another passage I've committed to memory) talks about how his days at Oxford were a search for love, "that low door in the wall," that was in a way filled by Sebastian. Caring for Sebastian, being at his side and learning there is nothing he could do for him, was how Charles learned about love. It helped, of course, that Sebastian and Julia were siblings. It is always easier, when the forerunner is family too.

(spoilers below, which matters especially if you want to experience the wild ride of "Till the End of the Night" yourself)

In Kuroda Sakaki's "The Bow," Takakura Kyu finds himself living in his father's apartment after his father's death. His downstairs neighbor Hideshima was his father's best friend and also his father's former archery teammate. In search of passion in his life and sick of sleeping around, Kyu takes up Hideshima's offer to learn archery. As he and Kyu get closer through archery, nascent feelings of desire start bubbling up in Hideshima, complicated by the fact that Hideshima had rejected Kyu's father Tetsu when they were younger and that Kyu also finds himself attracted to Hideshima. Hideshima, unable to bring himself to extricate himself from Kyu's advances, sleeps with Kyu, but then breaks things off when he spots Kyu's former sex friend Ei leaving Kyu's apartment in the morning. This and the closing of the archery dojo brings Hideshima and Kyu's relationship to an aborted end, and they disappear from each other's lives, until a year later, Kyu receives an email from Hideshima, announcing the reopening of the dojo, which Hideshima has purchased.

At the risk of accidentally making Hideshima into Jacob from the Twilight series, was loving Tetsu a forerunner for eventually loving Tetsu's son Kyu? Was Hideshima unknowingly preparing himself for the future love of his life, or is he still chasing after Tetsu's afterimage through Kyu? When Hideshima allows himself to be seduced by Kyu, he thinks, "I thought I had feelings for [Kyu] all this time. I've finally realized that I've been chasing after Takakura's shadow." Hideshima sees Tetsu in Kyu's form constantly: in his archery form, in the CD that Kyu fiddles with, in Kyu's feelings for Hideshima. But when they are reunited a year later in the archery dojo, Hideshima puts to rest the idea that he sees Kyu as a replacement for his father. He reassures Kyu that Kyu is his own person, and Hideshima's only apprentice.

It's thrilling enough to love both the father and the son; it is even more thrilling, as I think it is in Hideshima's case, to love both the father and the son and to become a pseudo-father to the son. Apprenticeship is a fatherhood ritual, sometimes literally in the case of craftsmen passing on their school of artistry. Hideshima is not looking to fuck Kyu's father through Kyu; he is looking to be a father figure that Kyu can also fuck. This is compounded by the reveal that Hideshima had moved into a downstairs apartment so that he could help Tetsu raise Kyu, the baby Tetsu had with Chihiro (the third friend of their archery trio and Hideshima's love rival) sometime after Hideshima rejected Tetsu. Hideshima had held Kyu in his arms when Kyu was just an infant. And in his role as archery teacher, he "gives birth" to another version of Kyu. Kyu's shooting form is not like his father's, but Hideshima's.

What Hideshima wants by the end of "The Bow" is not quite love, but connection (very archery master of him), something bigger than his own body, something that will land outside of himself, that is formed by himself but ends elsewhere, maybe even inside someone else (again, very archery master of him). When Kyu was first born, Tetsu told Kyu that humans can only find joy in other living things (very new papa of him). What he meant was a child, a wife, a partner. But in the end what Hideshima builds is a way to Kyu through archery. Even if Kyu and him separate, Kyu's shooting form will always be that of Hideshima's.

Is that love? Well, we are in the business of boys love, and not bows love (I will never stop making variations on this joke). So it must be.

The forerunner trope usually works like this: A is dead and B is sad about it. C is a brother, son, cousin, some other substitute for A. In his grief, B mistakes C for A. B eventually learns to love C on his own terms. In "Till the End of the Night," Hiura finds himself the lead prosecutor on a case involving the potential murder of his colleague and law school classmate Kageyama. He is haunted every night by dreams in which he and Kageyama have sex, a fantastical scene that disturbs Hiura because, while Hiura has always known Kageyama was gay, their friendship remained strictly platonic. While investigating the whereabouts of Kageyama's body, Hiura confronts Kageyama's younger brother Naoto, who bears a troubling resemblance to Kageyama and an inexplicable hostility towards Hiura.

Kageyama loved Hiura, of course he did; Naoto reveals that Kageyama slept exclusively with men who physically resembled Hiura, a fact that only serves to make Hiura sentimental over Kageyama, crying as he explains to Naoto, "I miss him. If he wanted me, he should have tried." As for Naoto, he was never close to Kageyama, and in fact no one but Hiura seems to see how much Naoto resembles his dead brother. Naoto, then, is a ghost of Kageyama that only Hiura seems to see. It is no surprise that as hope of finding Kageyama alive wanes, Naoto and Hiura are bound more and more closely together, eventually culminating in them having sex.

Here you might think you know where the story will go next. They find Kageyama's body. Naoto has some personal admission of vulnerability or feeling; perhaps he loved his brother after all, and his resentment towards Hiura was a misplacement of his grief. Perhaps it is Hiura who breaks down, and Naoto must hold him as they cry over Kageyama's death together. They have sex again; perhaps then they separate, thinking they cannot conduct a relationship so shadowed by the specter of Kageyama's death. Then, maybe, Hiura is walking down the street, and he catches a glance of someone familiar. He calls out. It is Naoto's name on his lips, not Kageyama's. The man turns around: it is neither of them. But that is enough for Hiura to realize what he does next.

Well, trust that Nishida Higashi will never go the conventional route and turn the trope on its head. What actually happens is that Kageyama turns out to have been alive the whole time, kidnapped by a woman who had a mental breakdown after her son died. Hiura is led by Kageyama's disembodied voice to the location where the woman has dumped an unconscious Kageyama and saves Kageyama from a near certain drowning death. Kageyama wakes up to find Hiura at his bedside. Hiura cries. The story ends. They do not have sex (not even in the bonus chapter), and Naoto never shows up again.

"Till the End of the Night" feels like a ghost story that is unable to fully commit to Kageyama's death. Nishida slips in little implications that Naoto only assumes his resemblance to the older Kageyama brother after Kageyama is almost killed, as if he is possessed by Kageyama; Naoto had longer hair, for example, but cut it after Kageyama's disappearance, and professes that he doesn't remember the night that he and Hiura had sex. Hiura, too, is convinced that he interacts at time with Kageyama and at times with Naoto. But if Kageyama was not dead, not even a coma, what possesses Naoto? Are souls in Nishida's world so easily dislodged? And if Naoto is merely a channel for Kageyama, why does Nishida spend so much time with Naoto berating Kageyama's life choices to Hiura's face? Why have Hiura and Naoto engage in any physical sex at all, when, rather memorably, there is a scene where Kageyama's ghost appears to embody a river that then goes on to sexually assault Hiura?

Nishida's theme is of regrets, of course: two people who failed to see each other for a time and thus missed the chance for connection, until a near death experience brings them to honesty. By using Naoto, Kageyama is able to give voice to the dirty side of his that he has hidden from Hiura all this time, and to be accepted by Hiura despite Hiura seeing the whole ugly truth. Whether Hiura could have any other response but acceptance, when he believed the alternative is accepting Kageyama's death, is a question for another time. Kageyama is a forerunner whose competitive spirit is too powerful to disappear politely into the sunset, like Takakura Tetsu. Or, alternatively, Hiura's desire to have a second chance with Kageyama is so strong it manifests in a perfect stranger and forces Naoto to be a passenger in his own body. No forerunner for him; he wants the original, and he wants it alive. Now that, I think, is truly boys love.

We never hear Sebastian's side of the story in "Brideshead Revisited." Charles goes on to marry one woman and attempt to marry Julia; Sebastian, as far as the novel is concerned, never sleeps with any women and ends up shacking up with a German man named Kurt who treats Sebastian like a dog. If Sebastian loved Charles, we'll never know. Waugh would probably say no, that Sebastian wasn't capable of it, but he was trying to write a story about days of sloth and excess eventually bringing Charles to the Catholic church, so giving voice to Sebastian's tragic love for Charles would be rather antithetical to his aims.

In "The Bow" and "Till the End of the Night," too, the forerunner/substitute's side of the story is pushed to one side. Naoto unceremoniously disappears from "Till the End of the Night" with a phone call. We don't even see his face, as if to emphasize that he was only in this story to look like Kageyama at a time when Hiura was vulnerable to such a thing. I wonder if Hiura will ever tell Kageyama about sleeping with his brother's body; my bets are on "no." As for the characters in "The Bow," I understand why Hideshima might not have responded to Tetsu when they were younger, but what happened in the time after Chihiro died, when Tetsu was a single dad and Hideshima was living under him? Kyu thought his father took advantage of Hideshima's feelings, but I rather think it was the other way around. Tetsu was waiting, biding his time, hoping Hideshima would see that they were meant to be together. Tetsu chose to raise Kyu all alone and asked Hideshima to hold his newborn son because, I think, he was hoping Hideshima would raise Kyu with him and be Kyu's father too. Even after Kyu presumably grew up and left his father's house, Tetsu and Hideshima remained upstairs and downstairs neighbors, close enough to hear each other's footsteps.

But a forerunner is always ahead of his time. He exists to become instrumentalized in the pursuit of true love. His only role is to usher in The Love Story: Tetsu by giving birth to Kyu, or Naoto by giving his body over to his brother. His love comes too early and remains unfilled and dies as Sebastian did, in a sunny garden among Franciscan monks, assumed to be happy because otherwise we feel bad. The true love narrative will always bulldoze through anything that shows the slightest hesitation, and the forerunner is the sacrifice that paves the way.

You can read both "The Bow" and "Till the End of the Night" on Manga Planet (formerly Futekiya).

0 notes

Text

SINCE I COULD DIE TOMORROW—FINITUDE IN PRESENCE OF LIFE

This is a post I previously published for a very short period of time and then deleted. I decided to publish it permanently after thinking about vulnerability and Sumako Kari, but having no backup, I had to rewrite it as I remember it. So here I am, rambling once again about Since I Could Die Tomorrow by Sumako Kari. There will be mentions of death and terminal illness here and there, and lots of…

#nora aaaaaa#much love to this post which is full of interiority and vulnerability#it is so difficult to be alive in this world#we have only our bodies and our bodies will betray us#there is nothing we can do about that except wait for the betrayal to come#all acts of human connection are breakwaters meant to stave that off#it is hard to build them and they will crumble#and the only true thing in this world is helping build them for yourself and for others

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you don't mind and have the time, can I send you BL challenge questions? Thx

You are always welcome to send me questions! However, I have to note that I am criminally bad at answering any questions that are structured like "What are your top [x] favorite [y]?" in part because I have a memory like a sieve and have to do a lot of soul-searching to remind myself of things I've read (I promise I'm working on a private tracker that will help me with this) and also because I just don't have very strong "tier" feelings. I appreciate so many things but all for different reasons! So if I don't answer, it's often because I'm struggling to come up with a satisfying answer. It may take me weeks; it may even take me months, but I am thinking.

However, please don't take this to mean that I don't want your questions! And if you are interested in dropping me recommendations or just want to talk about a series I've/you've read, please do!

(Side note: I'm sorry to the handful of people who have been sending me kind messages about how much you've enjoyed reading my posts. I've seen them! Thank you for sending me them! I very much want to send replies but I Have A Problem with publicly sharing nice things people say about me and if you're anon, that is the only way to acknowledge receipt... so please know I saw your messages and I appreciate them!!)

1 note

·

View note

Link

#perfect review for a perfect series#i wish i had known earlier that it was licensed bc i would have recced it everywhere

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

MIDNIGHT RAIN & ONE ROOM ANGEL—IN PRAISE OF PATHETIC (FICTIONAL) MEN

As some of you may have seen on my Twitter, I felt the pull to reread CTK‘s Midnight Rain and wanted to follow that with Harada‘s One Room Angel somehow. It was subconsciously done but in hindsight, my brain was onto something. So I wanted to hijack some of your spare time and attention span for a couple of minutes to talk about the main characters of these two series, Midnight Rain‘s Ethan and…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

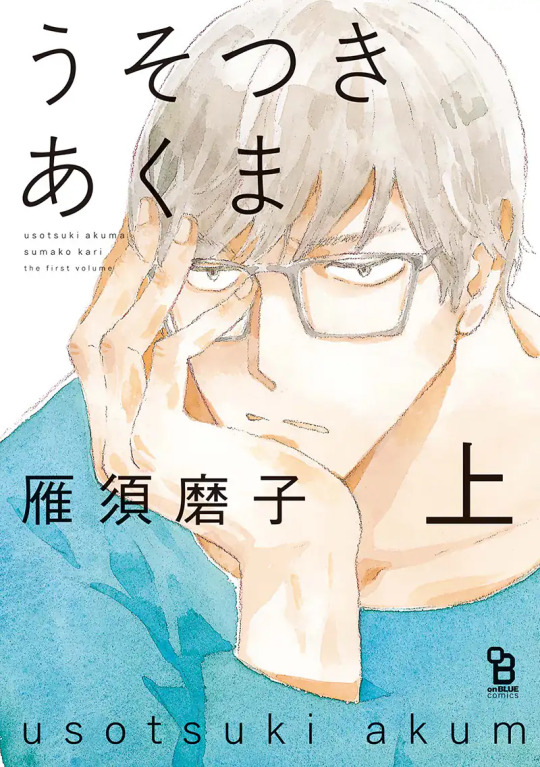

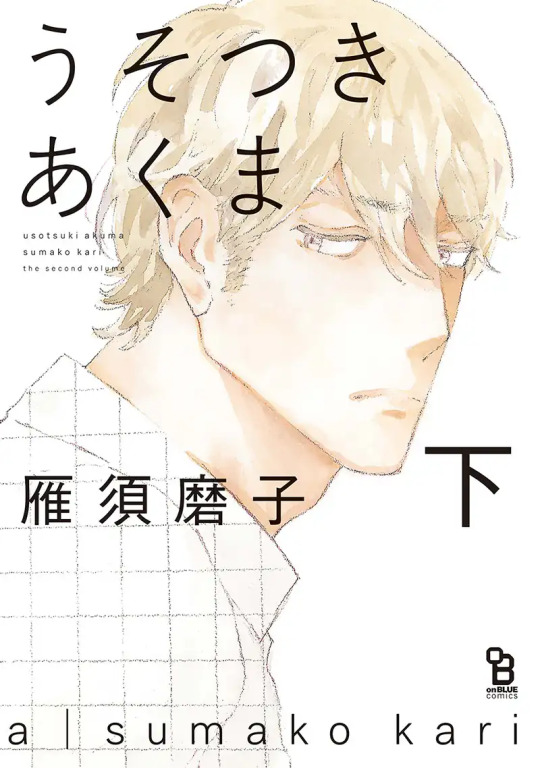

14/50: the tortured mangaka department (kari sumako, "lying devil")

In the spectrum of love-hate stories, there is nothing for me that can top a story between two authors or artists. In other versions of this trope (e.g. rival salesmen, delinquents from opposing gangs, classmates competing for rank, aces on opposite sports teams), the rivalry is the starting place. The characters are filled with resentment, jealousy, irritation. This is the activation energy necessary to generate the romance; after all, the opposite of love is not hate, etc. If there is admiration for the craft (and there often is, like in the case of 10 Dance), it is a begrudging one. The other is your competitor. You appreciate them from the vantage of point of putting yourself in their position and wanting to be them. "If only I could do that." "You make me want to do that." Love, in this case, helps the characters make peace with their messy feelings and put aside their egos. Love smooths over, love overcomes.

Not all stories about two rivals are love stories. But all stories about two writers who like each other's work is, ultimately, a love-hate story. Because there is no greater praise one writer can give another writer than, "I fucking hate you." When a writer reads another writer's work and loves it, he momentarily loses his identity as a writer—he becomes a reader, an object to be guided and seduced and manipulated by the other. He is compromised, he is made vulnerable. His appreciation forces him to surrender. To submit to this, over and over again, is a story that starts with love and becomes hate, before wrapping right back around again.

So this week, let's talk about Kari Sumako's "Lying Devil."

"Lying Devil" opens on Amari Eiichi, a mangaka who in his younger days was an assistant to (and mega fan of) fellow mangaka Ugo Satoru. Five years ago, Ugo had broken off their nascent relationship when Amari debuted to much acclaim, citing his inability to be truly happy for or praise Amari's work without being overwhelmed with professional jealousy. Despite this, years later, Amari and Ugo are still carrying on a strained fuckbuddy relationship that Amari finds unsatisfying and Ugo finds overwhelming. They carry on this way, on parallel paths that rarely intersect except for athletic late night sex and prickly but strangely intimate phone calls, until Ugo's poorly planned attempt at making Amari jealous (in part by going mountain climbing with another mangaka named Yara Shu whose presence in this story is so odd that I wondered for a while if he was a cultural reference I'd missed) backfires and causes Amari to dump Ugo himself and go fishing for a new boyfriend. It doesn't work—after throwing a drunken tantrum, Amari finds himself going back to Ugo, who has begun spiraling into a black hole of depression and writer's block that Amari tries valiantly to help him out of. That doesn't work either—despite Amari's best attempts to bind Ugo to him, Ugo ends up physically and artistically withdrawing, finally leaving his apartment, manga career, and Amari and disappearing into the night.

In other love stories, the resentment is a bug; in Amari and Ugo, it is a feature. Their happy ending is to stay in this push-pull of love-hate, to be drawn in by the other's talent only for that talent to stab them in the heart. A lesser writer than Kari might have acquiesced to the temptation dangled by chapter 11, when Amari helps midwife Ugo's struggling series through writer's block, to come up with a neater happy ending for these two. Perhaps instead of Ugo showing up at Amari's door four years later with a self-published collection of oneshots, they should have written a manga together or made up a new name under which they could together publish original doujinshi. After all, Ugo won his first award by taking story ideas from his good friend Chiba, who gladly handed over his story ideas to Ugo because he believed he'd never be a mangaka himself.

But Ugo and Amari are Kari Sumako's creations, and in all three of her three bl works on Futekiya, she features characters who hold strong to their principles, no matter how miserable it might make them, even if it loses them everything. What drew Amari and Ugo to each other was the desire to see each other and be recognized, in their work as well as in their feelings. Amari was a fan of the work Ugo made before they met. He is, and always will remain, a fan of Ugo's work. To strip away Ugo's ability to make work that is wholly and unapologetically himself, even if it is in service of something good that was created with Amari's assistance, is tantamount to creative "unaliving." It is no kindness for Ugo to be told that with Amari helping him, his work was "great" and "unexpected" and imbued with new feeling. "My god," he thinks, ruing over the impending marriage of another mangaka friend and this "marriage" of his and Amari's art. He must escape this—in their union they have both become smaller, lesser people, or at least smaller, lesser creators. And he is right, for once they are separated, Amari writes the most successful story of his career, and Ugo is finally able to draw again.

This is not a healthy way to think about writing, of course. To live with jealousy so ruinous that it eats away your life and makes you abandon your apartment, manga serialization, and fuck-buddy-ex-boyfriend for four years is, obviously, the mark of someone who maybe needs to stop drawing manga for a bit and/or go to therapy, and is certainly a red flag when it comes to pursuing a romantic relationship. In the afterward, Kari states that "Amari would be happier if [he and Ugo] broke up," only to be visited by a doodle of Amari who, threatening her with a kitchen knife, forces her to recant. Well, while Kari must answer to her own creations, I don't: she was right and should say so. Amari would have been happier if he and Ugo had split up and stayed split up.

I joked (I was being serious) in my post on Marukido Maki's "Pornographer" that all writers are infested with inherent badness. Certainly Ugo more than proves the rule. He is high-handed, overbearing, controlling and dismissive of Amari all at once, a bad friend and an even worse boyfriend. He wants Amari at his beck and call, because it proves that Amari loves him and would do anything for him. He knows Amari loves him and wants sex from him, but treats their time together like meditation or time at the gym or, worse, a trip to the restroom: something that helps reset his rhythm, but nothing sacred or special. Perhaps he has to treat Amari this way, because it tricks his mind into forgetting, for just a second, that Amari is sacred and special—not because of Amari's feelings for Ugo, but because of Amari's talent at manga, which tortures Ugo so much that he cannot even bear to read Amari's manga, not even a single glance.

What Amari deserves is supportive friends, editors, and fans, who would all appreciate Amari's ability to transmute feelings into storyboards and celebrate his determination to meet, even exceed, deadlines. Amari is so humble, so forgiving, so generous. He is even handsome. Inspiration and art come easily to him; he either thinks nothing of his talent or nothing of talent at all. He has so much talent he is even able to share it with Ugo, when Ugo is at his lowest. It is right that Ugo should grovel at the end, dogezaing in the entryway of Amari's entryway just to be allowed the privilege to see Amari again.

But my god! Doesn't that eat away at you? Don't you get why it might have eaten away at Ugo? Why doesn't Amari ever suffer for his art? Why is it so easy for him to create manga? Why does Amari never get jealous of Ugo's work? Why are all his hangups only about Ugo as the lover, Ugo the boyfriend, and never Ugo the mangaka? Is it that he isn't threatened by Ugo's work, and that's why he is able to read Ugo's work without feeling a stabbing in his heart, sometimes a stabbing all over, the furious desire to rip the pages to shreds and then eat them, because maybe in doing so you can totally crush the existence of this other person who is imbued with the talent you so fervently desire while also bringing that talent into your own body?

Isn't it more normal to think this way, to fall into Ugo's orbit of insecurities and jealousy?

Or is me saying all this just telling on myself?

The first time I read "Lying Devil," I was angry on Amari's behalf. "This fucking bastard!" I chanted along with Amari. "This scum of the earth! This coward!" The second and third time I read "Lying Devil," I thought to myself, it is Amari who is the monstrous one. A good man who is able to write so much so easily is not a normal man. He was put on this earth as a trial for Ugo, and for people like me, who are like Ugo. There are so many more of us who are like Ugo and not like Amari, who struggle with our own inadequacies, who face down a blank page and run away. Like Kathryn Chetkovich who writes in her autobiographical-ish essay "Envy" about dating a struggling novelist who ends up being Jonathan Franzen. In her essay, she remembers remembering a passage of his, then goes to find the piece he wrote, and realizes, "It wasn't as good as I remembered. It was better." Even her memory's recreation of his prose pales in comparison to his actual prose. That is Ugo-core.

Even "Look Back," which at first glance seems to be the opposite of "Lying Devil" with two main characters who work together to make manga and encounter tragedy when they are apart, is more Ugo-core than Amari-core. It is her jealousy and the drive to create something that is wholly herself that inspires Fujino to make manga. The drive to be "superior" in some way to Kyomoto even inspires Fujino to lie: that she quit manga so that she can submit a one-shot to a magazine contest. This drive, this lie, connects the two parallel worlds of the story: karate-athlete Fujino also lies to Kyomoto that she is thinking of writing a manga. Some writers, I’m sure, are inspired purely by the desire to put art out in the world. But how many more of us do so to prove a point, that we are in some ways superior to someone, and specifically the good writer whose story incapacitated us, reduced us to simply readers, held captive in the giant hands of a worthier talent, pathetic and cute and small?

The fourth time I read "Lying Devil," with all this swirling in my head, I found myself going back to the second chapter, to the scene where Ugo drags Amari to a drinking party with their other mangaka friends after they've had sex. Ugo, half-asleep on Chiba's knee, suddenly calls out Amari's name, and Amari responds immediately. Draw me a scene of Ikebukuro from a high-angle aerial shot, Ugo continues, as if lost in time and dreaming about when Amari used to be his assistant, much to the amusement of everyone around them. Amari goes home happy. "At that moment," he says, "Ugo was awake. He woke up, covered up what he had let slip, then fell back asleep."

The first time I read this scene, I had taken Amari—and thus Kari Sumako—at his word. The second time, I began to doubt. The third and fourth time, I wondered if maybe Ugo had called out Amari's name, just to test Amari, just to see if Amari would respond immediately. And when Amari called out "yes" like a reflex, like his body would always respond to Ugo wanting him, no matter the time or place, he'd hated the small petty part of himself that needed to test Amari, hated the fact that this was the only way he could show Amari that even in a group of their peers, even with Amari at the top of his career, Ugo can still bring him down like this, to the lowly assistant who will always respond to Ugo calling for his help. And it would never occur to Amari to think of any of this, Amari, ever the romantic. Of course Amari would only see the good. Of course Ugo could never bring himself to admit the bad. How clever of Kari to test us with this scene so early in the story, before we've even gotten to fully know Ugo. How sharp the writing, how perfectly characterized.

And then I thought to myself, goddamn you, Kari Sumako. I fucking hate you.

You can read "Lying Devil" on Manga Planet.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

13/50: you got a childhood friend or lover in me ("try & i love you," "derail," and "love song of the cracker ball")

Sometimes when you don't like a trope you end up devoting your entire week reading Futekiya's back catalogue of the trope and come up for air on a Sunday realizing you should probably say something about it. So, let's talk about childhood friends to lovers.

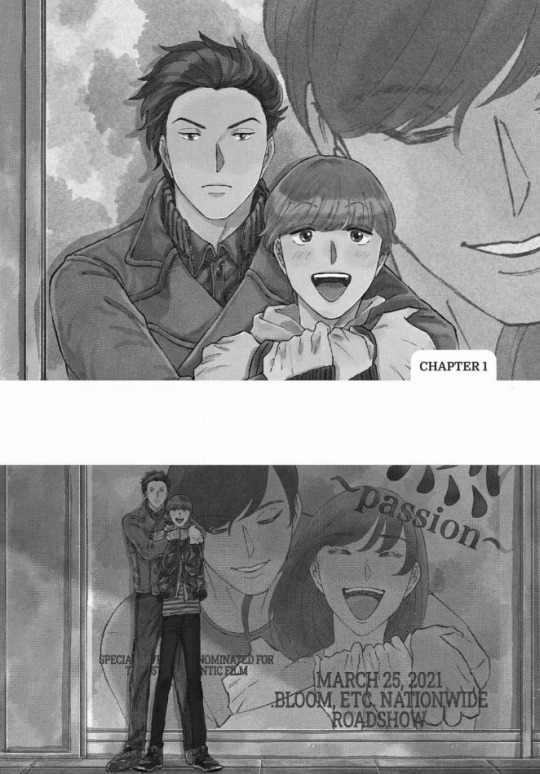

The splash page of the first chapter of echo's "Try & I Love You" features main characters Ren and Takumi imitating the poster art of a romantic movie they later go on to watch on their first date. This is the movie Takumi convinces them to pick it over Ren's suggestion (some sort of MCU parody) because "if we don't watch something like this, we won't feel the love, right?" The movie is a disaster; they both are so dissatisfied that they end up going to see Ren's pick immediately after. Worried that they've slipped back into friend territory, Takumi and Ren hold hands ("Friends don't do that, do they?") only to realize that friends, in fact, do hold hands, or at least they did, as friends, when they were younger. What else, then, could they do to differentiate themselves from the mere friends they used to be? Hugging, hobbies, hanging out, compatibility—these are all shared by the "lesser" couplings of friends or fuck-buddies. So, Takumi concludes, it must be sex after all. Or is it?

I was not blown away by "Try & I Love You," but I very much appreciate its existence. Unlike many other iterations of the "childhood friends to lovers" storyline (some of which I'll discuss later), it is the rare, unadulterated version of this trope: two childhood friends who harbor no romantic interest in each other before they decide in a moment of "why not?" to date each other. Accordingly, the plot consists entirely of Takumi and Ren struggling with what dating means for their friendship, if it means anything at all. In chapter 2, Takumi complains to his coworker that "it doesn't feel like we're lovers at all." They are too comfortable with each other and know each other too well. Instead of going out, they rent a bunch of movies and watched them at home. Instead of a popular cafe, they go to an all-you-can-eat-crabs buffet. They cuddle and make miso soup for each other after a night of drinking and go to a gyoza festival where they feed each other and even though Takumi's heart pounds at seeing Ren's happy face, he still wonders, "What if I tell Ren I want to date like real couples?" What the hell are you talking about, the reader may be yelling at this point. Are you not already dating like a real couple?

This week I was chatting about relationships and heteronormativity with my good friend Caitlin, who always has something smart to say. She reminded me that part of rebuking heteronormativity is "figuring out who you are versus what you think you are based on stories." In the case of "Try", the stories are contained in things like the movie Takumi and Ren imitated in chapter one, a romanticized fantasy narrative about how love should be performed and how dating should feel. Love feels like butterflies in the stomach, demands certain date spots and behaviors, and most importantly should not be comfortable during the honeymoon period. It should include some sort of physical manifestation of sexuality, because in these stories, you have sex with one person and that one person is the partner you date exclusively. These stories are predictable and iterative patterns of behavior that, for many people and for Takumi and Ren, make us doubt love even when we are staring it in the face.

In our society and in Takumi and Ren's, these stories are also straight ones, the heterosexual part of heteronormative. Ren's ex-girlfriend Sayaka breaks up with him because she realized she is attracted to women, and in the aftermath, Ren realizes he was distracted by years of heterosexuality into thinking that his feelings for Takumi cannot be the same romantic feelings he has for Sayaka, simply because Sayaka is a woman and Takumi is not. Later, when Takumi misunderstands Ren's motivations for dating him, Ren comes to a second discovery, even more radical than the first: that the issue is not whether Sayaka is a woman or that Takumi is a man, but that Ren wants to stay with Takumi, even if it means chasing and begging and fighting for a chance.

If love is anything at all, echo argues, it's not in sex or kissing or holding hands. At its most basic core, it must reside in the desire to be with the other person. For Sayaka was similar to Takumi in the ways that attracted her to Ren: they have fun together, they like the same things. But Ren was willing to give up Sayaka, simply because she said she loves women. And Ren wanted to date Takumi, even if Takumi never expressed an interest in men.

There is something dangerously close to aromanticism in Takumi, and part of me thinks echo could have gone the full nine yards with that. "Up until now, I've never been in a relationship because I fell in love with them," Ren admits to Takumi. Later, he explains, "I think girls are cute, but I've noticed that I don't want to know more about them, nor do I have romantic feelings for them. I don't feel anything in particular when I see my fellow men, either." But here echo stops short, and creates a unique "gay for you" twist but for alloromanticism: Ren's feelings for Takumi are uniquely romantic and inspire him to want to be with Takumi. And that's fine; we are in the boys love genre after all. But after the confession, "Try" loses its odd appeal and becomes a kind of awkward sex romp, with Ren getting angry that Takumi is trying to practice anal sex on his own and an epilogue where it turns out that Takumi is actually an insatiable beast over, of all things, Ren's sleeping face. I can't help but wonder what, say, ymz would have done with Takumi and Ren's relationship—but, well, "Good-bye, Heron" already exists.

On the other hand, Aiba Kyoko's "Derail" is "childhood friends to lovers" by way of false advertising. Hikaru and Haru are not childhood "friends" at all, but rather two lovers who have used childhood friends as a front to hide behind. Haru is a gloomy playboy who has spent most of his life devising ways to keep Hikaru unreasonably close to him, and Hikaru is a classic maladjusted people pleaser who uses his nice guy persona to hide the fact that he derives almost all his self-worth from being wanted by Haru. Both of them have the makings of psychopaths in another story, but here they spend their energy playing tortuous mindgames in their own heads while from the outside they progress, totally normally, from friends to dating to lovers. That neither of them have any real friends other than each other becomes increasingly obvious, because any third party would have called out this relationship for what it is from the start. Oh, your childhood best friend sleeps with you in the same bed and forbids you from bringing girls home? Oh, your childhood best friend makes googly eyes at you over breakfast and lets you jerk him off? Come on, man. Be so fucking real with me right now.

The issue is, of course, that the default assumption of heterosexuality has Haru believing he needs to be playing some sort of Soulslike game with Hikaru's feelings before he can get to his goal of dating, while Hikaru believes he's unilaterally trapped Haru like a codependent spider in a web of neediness. As Haru says, when people in tense situations are pressured to pick between two unreasonable choices, they're convinced they must choose one of them. So if you are two men who want to be in each other's lives forever and to be each other's number one, heteronormativity has you believing the unreasonable choices are either to (1) not do that, which isn't an option, or (2) slide everything under the cover of "childhood friends" and hope no one, least of all yourselves, takes a closer look. This is a losing proposition, but Hikaru and Haru are so busy believing the story they tell themselves and everyone around them of being "childhood friends" that they simply cannot realize they are in an impossible situation, being forced to make unreasonable choices. They must, as one might say, find the secret third thing, which is not so secret here: just admit you love each other and leave the rest of us alone!

Unlike Takumi and Ren, I don't think Hikaru and Haru were ever friends or at least haven't been friends for a long time, too caught up as they were in stretching the boundaries of acceptable "childhood friends" behavior. And I think there's a part of their creator that agrees with me. Amusingly and in contrast with "Try," the epilogue of "Derail" features the two of them going to a hotel for a date, not to have sex, but rather to spend an evening playing video games and relaxing. This might be the closest we ever get to a "lovers to childhood friends" reverse trope, or at least as close as we'll ever get without reincarnation or isekai.

Suzumaru Minta's "Love Song of the Cracker Ball" splits the difference by featuring one character who is learning how to turn a hypothetical openness to the other gender into a very real interest in one specific male friend and another character who is doing his own one-man show of "Derail" but, like, more normal about it. Wako and Takeo have been neighbors and childhood friends for a very long time, and Wako had been depending on remaining Takeo's friend to stay Takeo's number one. When that position is threatened by Takeo suddenly musing that he'd be open to dating a guy, Wako loses equilibrium entirely and ends up confessing his long-time crush to Takeo, who of course suggests they try dating. Wako is somehow even less prepared for this possibility than he was for getting rejected, but after a lot of hand-holding and hijinks and a poorly thought out plan by Wako to figure out what inspired Takeo's gay awakening, they manage to make a proper relationship of it.

(Before we get further in this review, can I just say that I loved this story? Wako and Takeo's friendship feels so lived-in, where you can tell they are two characters with a past who are used to dealing with each other, with Takeo able to pinpoint even Wako's wildest insecurities and Wako never letting Takeo control the pace, even when, towards the end of the story, it threatens to destroy their burgeoning relationship. Suzumaru draws big, dynamic expressions for her characters that bring them to life, making even frail Wako feel explosive, and isn't afraid of making her characters not look handsome if it serves the comedic timing. In particular, I love the panel at the end of chapter 1 when Wako yells "good fucking job!" Wako's face is ugly from the exertion of screaming, and Takeo literally looks like he could fall off the rooftop stairs and into a Crayon Shin-Chan panel. Wako and Takeo's friend Manaka is my favorite side character and would deserve his own spinoff if he wasn't imbued with the pansexual appeal of a certified pretty boy. He does a surprisingly good job playing emotional referee, and it speaks to the strength of their friendship that he never once seems worried that his friends will stop needing him after they start dating each other.)

"Cracker Ball" is a spin-off of "Cupid is Struck by Lightning," and while it isn't necessary to read "Cupid" to enjoy "Cracker Ball," Takeo and the decisions he makes make a lot more sense when you have. In "Cupid," Takeo is a side character who is brought into volume two to add spice and intrigue to main characters Ao and Shingo's relationship. Arrogant, brash, and determined to teach his underclassman a lesson, Takeo comes out the other side of "Cupid" realizing that he wants what Ao and Shingo have: a love so important that you'd be willing to be retraumatized just to prove that you need and want to be the other person. That's why he's so upset at what initially looks like Wako being homophobic, only to be totally disarmed when Wako declares, "I am the one who loves you the most." "Cracker Ball" softens the blustering egocentric Takeo we see in "Cupid" (though that may be because "Cracker Ball" is partially through the POV of Wako, for whom there can be no better man than Takeo), but the animating drive of Takeo is still to be someone's number one. When the veil of heterosexuality is lifted, he realizes he's had that all along in Wako.

Takeo is the most straightforward of the six men we see in these three series. Unbeholden to shame or crippling anxiety, he ends up cutting right to the bone of the childhood friends trope. When he corners Wako in chapter 2, he doesn't mince words and poses the questions that all friends-to-lovers pairs must answer. What can you do when you are already family, when there is already a bond that cannot break? What is beyond that, and why is it worth reaching for? "Childhood friends to lovers" is so powerful because it is a story that asks the characters to risk so much. It is a story that believes being together is worth potentially altering something that already works, because that is the only way to together explore something that may not. It is about moving into that uncertain future together, with a person both familiar and strange by your side. It is a man you have known all your life, but suddenly, he looks different. He is on the other side of a line, and that line is love. But he holds out his hand, and when you grab it, you see him for who he is. "See?" he says. "There is nothing to be scared of."

You can read all three series on Futekiya.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

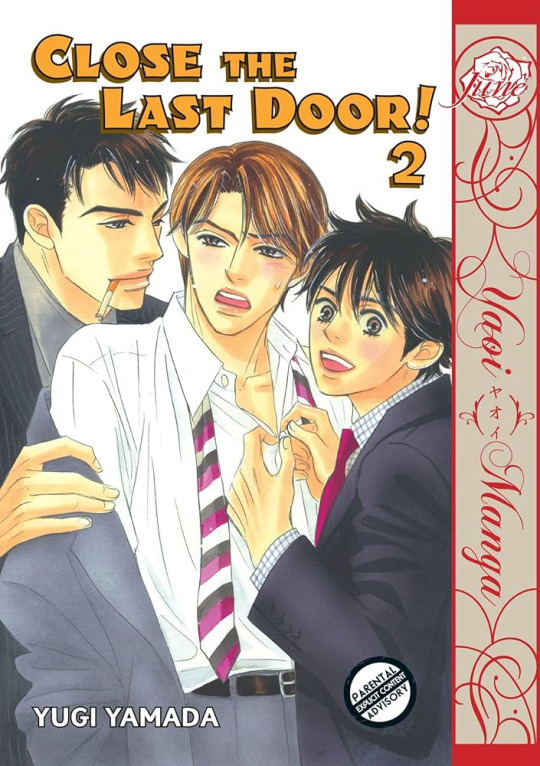

12/50: second draft (marukido maki, "pornographer" series)

Before falling back into bl fandom (thanks for nothing, June!), I was watching a lot of videos about conscious consumerism and booktok fandom. For a while, despite being hobby-less, I found myself contemplating how more and more modern hobbies have more and more become about consuming, buying, purchasing, collecting ever more things. Even reading has become a hobby about consumption rather than contemplation or meditation. In the loudest, most obvious corners of "reading as fandom," if reading is that, the hobby is defined by book hauls, buying new releases, subscription boxes, exclusive editions—the hallmarks of buying as a hobby rather than doing.

How do we make reading a hobby that isn't about spending money, and how, specifically, do we do this in the context of bl manga? I think it feels even more potent in bl manga because we the readers feel it is our obligation to support it, and more importantly, that our support allows the hobby to continue and proliferate. For example, we believe (and I am not saying we are wrong to do so) that if we buy more licensed bl and support reading/buying bl on their official platforms, the companies will keep licensing new series and even bring us the specific series we want. Too, as the hobby becomes more normalized, we encounter new and different (and, sometimes, bad) ways of doing fandom, like sharing screenshots of scanlations while tagging the authors. Faced with bad behaviors and bad actors, we try to rehabilitate our image, convince people that we are serious, we are a force to be reckoned with, that we matter. And how do we do that in this current world, if not through money?

But I bring these questions to you not to answer them, but to disregard them. As a consumer, as a reader, as a hobbyist, I don't have the responsibility, and certainly not the ability or the know-how, to fix the problems with the industry. I think of myself instead like an ancient wine priestess: mystic and superfluous, responsible not for portents or prescriptions, but rather for doling out the simple pleasures of the present. Others may come with solutions; I, for one, prefer to spend my time talking about bl delusions.

This is of course why I feel so strongly about writing about bl, and doing so in a serious way. It keeps the hobby fresh, forces me to revisit the things I have already bought, and to bring them alive in a way that isn't about buying more things. Rereading, sometimes over a period of years, coming back to stories as a changed person and discovering new reasons to love them—these are ways that I already interact with non-bl anime and manga, that feel normal and even laudatory as I've gotten older. I want to make that a way of interacting with bl too, that the bl stories we read are capable of having the same kind of lasting power, the same kind of emotion.

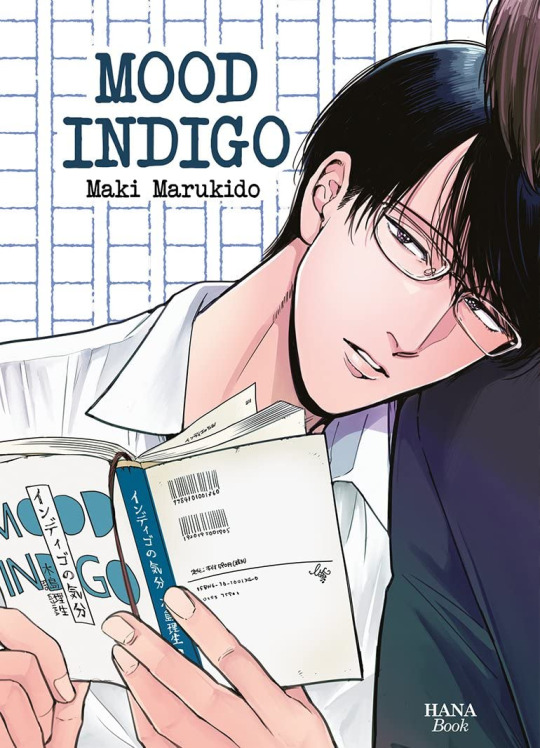

And so, this week, I want to talk about Marukido Maki's "Pornographer" series, a story about writing that I have read and reread many times.

In 2020 I got a Futekiya sub simply so I could read "Pornographer" and even wrote a little blurb about it. Normally, this would mean that I would consider this series off limits for another long post. After all, what more can I say that I haven't said already? I stand behind every word of my first pass. Kijima is a deliciously bad man who seems designed by Marukido specifically to torture Kuzumi, an innocent himbo with a very rich inner life. That Kijima manages to snag Kuzumi and keep him through the end of "Pornographer" speaks not to Kijima's virtues but rather to the suspension bridge effect of it all. Caught up in Kijima's elaborate lies and then very dramatic reveal of his lies, then strung along for two years while Kijima tries to find himself and a way out of his writer's block, Kuzumi really had only two options: strangle Kijima himself or fall in love with him, and the genre isn't called "boys' ligature."

If there is one fault with "Pornographer" and "Playback," it is that Kuzumi's interiority is not as well-developed as Kijima's, despite being the POV voice in "Pornographer." But perhaps that is because Kuzumi is so normal. It is normal to fall for the seductive, flirtatious older person who talks to you about your erection, it is normal to be upset that he lied to you for months and then ran away after a night of impassioned sex and seven orgasms, it is extremely normal to be furious when he then tries to recreate your meet-cute with another man. What is less obvious, maybe, is what keeps Kuzumi in love with Kijima. This time, in 2025, as I reread the series and especially "Playback," I think what he was drawn to was Kijima's natural loneliness. Kuzumi himself wasn't able to articulate this until chapter 3 of "Playback," when, passed out and lightly concussed from falling down a flight of stairs, he remembers the moment he started falling in love with Kijima. He had been washing Kijima's hair and talking about his parents eventually replacing a beloved family pet who had died of old age. Kijima implies that Kuzumi's family had gotten a new dog because Kuzumi had moved to Tokyo. "If I were your parents, I'd probably be sad too. I'm sure their home without you there was very quiet and lonely."

Kuzumi may not realize it, but in that concussed montage of the moment he began falling in love with Kijima, thinking of Kijima talking about loneliness, Kuzumi has finally seen Kijima as a writer. Writers are inherently lonely people. To write, or at least to want to write, is to be separated in some way from the normal flow of life, to be an observer even in your own life. Like all sentimental writers (myself included), Kijima has a bad habit of being nostalgic for something he has not yet lost. He is unable to be in the moment and enjoy Kuzumi washing his hair without thinking of himself becoming Kuzumi's parents, eventually left with a quiet and lonely home, having allowed Kuzumi to walk out of his life. Perhaps he thought of himself like Kuzumi's dog: helpless, fading, able to enjoy Kuzumi's kind ministrations only because it is temporary. Even at the very end of the series, when in "Spring Life Part 2" Kijima agrees to move in with Kuzumi, Kijima is unable to do so without thinking of endings. "Don't get sick of me and toss me out on the streets," he says, to a man who has had more than enough reasons to do just that and has resisted the impulse each time.

At this height of happiness, about to cohabitate with a man who loves him so much, Kijima remains tortured by happiness as a phase that will pass, of happiness that speaks to the possibility of future loneliness. And this is what inspires him to get out of bed, a bed he is sharing with a man who loves him so, so much, so that he can write. There is no panel that speaks more purely to Kijima's nature than the last page of "Spring Life Part 2." He sits, solitary, at the dining table in the dead of night, smoking. He is separated from the man who loves him by a door, a door that man has shut on purpose. It is because that man loves Kijima so, so much that he has closed the door, so that he does not interrupt Kijima's writing. In that moment, Kuzumi does not call Kijima by any of his names. He says, instead, from a tender but melancholy distance, "goodnight, sensei."

This distance between Kuzumi and Kijima is what brings me back to the "Pornographer" series time and time again. Younger me wrote that this series was "an ode to the idea that love is not the end of two people's identities as individuals, that a relationship is not about two halves becoming a whole, but rather a space for two people to be whole together, to be together while being apart." And I do love that and agree, but now I wonder if all that is only true because it is reflective of how Kijima—and maybe Marukido herself—thinks about writing. Perhaps to Kijima, the defining characteristic of a writer is some inherent badness. Or the other way around, that writing makes a person bad, hence why he, and Gamouda, and Kido all are "bad people." This "badness" means for Kijima that he feels forever quarantined from his friends and family and most of all from Kuzumi, who is bright and wholesome and untouched by writing of any sort. The only person Kijima feels no shame in holding onto is Kido. Kido can never reject him, because Kido at least was once a bad person—that is, a writer.

There's an uncanny parallel between Chapter 4 of "Playback" and Chapter 6 of "Mood Indigo." In both, there's a sense of leave-taking, that Kijima and Kido are nominally putting their relationship to bed, while secretly keeping silent about their own lingering feelings. In "Playback," Kijima is firm in his verdict that he and Kido would have never worked in a relationship, and Kido seems to agree. But I think there's a reason Marukido doesn't show you Kido's face in that moment. Because I think in that moment, Kido is not being a good friend, or a good editor, or a good person. I think in that moment Kido is relapsing. He is remembering that he was once a bad person, and that as a writer his heart can violate the laws of time and physics, letting go of a thing he never had in the first place. The awful truth is that writing made Kijima and Kido into twin flames. That doesn't mean they can be together, but it means they'll always share something Kijima and Kuzumi can never share. Perhaps that is why throughout the entirety of the series, Kijima never "reads" Kuzumi in to the events of "Mood Indigo." He'll share the secret of "Spring Life" and Gamouda, but not this. Well, perhaps that is the role of the editor, that fate that Kido eventually surrenders to: to transform a bad story into a good one, and to show the writer—Kijima—in the best light possible.

You can read the Pornographer series on Manga Planet (formerly Futekiya). One day we will get it in print. I believe it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the talking flower," by asada nemui

Reprinted from a now defunct newsletter previously hosted on TinyLetter.

I've been thinking a lot about body horror and plant imagery recently: bodies turning into plants, plants becoming human, how to make the language of flowers or the idea of flora into horror. When it comes to magical realism and flowers, the most obvious touchstone in fanfic is hanahaki disease, but there is something safe and tame in that—the physical manifestation of unrequited love is still sad, but it feels like the modern bl version of consumption, a more romantic tuberculosis. What I want is something like the structural plant people in the movie version of "Annihilation" or the one time in NBC's Hannibal where a corpse is turned into a flowering tree in the middle of a parking lot (of which I will spare you a screencap).

"The Talking Flower" is the second story from Nemui Asada's "Dear, My God" volume, and the plot is simple: main character Hana, a flashy careless businessman, drunkenly stumbles across a plotted plant (which resembles a head of a lettuce if it were also a rose at the same time) sitting abandoned in front of the florist shop across from his apartment. Hana picks it up and takes it home with him, only to learn that it's a talking flower—or more precisely, it's a flower "that God has allowed to talk," and only Hana can hear him. Hana, who lives a lonely single man's life, warms up to the idea of having what amounts to a very intelligent stationary pet, but is taken aback when he wakes up one morning to find that his cabbage rose has become a full, naked human being, or at least a thing that looks like a human being, even if it can only drink water. Worse still, the plant man is the spitting image of the florist shop's owner, a man named Miki, with whom Hana has a bad relationship.

There's nothing outright body horror about "The Talking Flower," but Asada adds her own flourishes with her art. Human!Miki and his florist shop are almost always conveyed in heavy shadow with lots of black and grey, as if Hana and Miki are in the eternal dark when their paths crossed (which is not untrue). In contrast, Hana and plant!Miki share scenes almost entirely in white space, including dream sequences where Hana gets to take plant!Miki to a botanical garden. When Hana wavers and begins to question how human plant!Miki can be, Asada brings plant!Miki into half-shadow: his face lit up by a TV screen, standing at the doorway waiting for Hana to come home, asking to share Hana's bed. Hana's attachment to plant!Miki is pure and wholesome, but Miki's presence is nevertheless suffused with eeriness. Asada never lets you forget that he is not quite human, even if Hana does.

The kicker is, of course, the ending, and if you mind spoilers you can skip this section.

Miki turns back into a flower; of course he does. This is the price all flower metaphors pay: the eventual disintegration, the fallen petals, a temporary bloom. Think Beauty and the Beast. The plant always dies. Nemui's twist, though, calls down a many-faced God who ends up being behind both Hana and Miki's fates and leaves open the question of how much of Miki was really human and how much of him was a potted plant on which both Hana and Miki projected their loneliness. In the end, the two humans meet and are given a second lease on life and, perhaps, their relationship. In the realm of bl or bl-adjacent manga, this is the trope ending, which isn't a complaint. After all, one of my favorite Ima Ichiko oneshots, "Always a Holiday With You," which you can find in her "Five Box Stories" collection, is this but without the plants. There, a high school boy is suddenly given custody of a shrunken version of his crush, a classmate that is currently in a coma due to an accident. A smarter writer would say something here about how this is just the old fanfic trope of hurt/comfort but taken out for a spin, which, probably true!

Like "The Talking Flower," "Always a Holiday With You" keeps ambiguous whether the relationship kindled by the magical realism remains after the spell has ended. There's probably more to be said about what these kinds of stories say about the idea of romantic love, and specifically how much of what we love is our own personal—and thus, potentially false—versions of the other. But for today, what I find the most interesting is the contrast between a human turning into a flower and a flower turning into a human. With the former, the fear is about losing freedom and freewill, becoming something that cannot express itself or feel, wholly dependent on the forces around it for movement and sustenance. In Miki's case, Asada argues that his life before Hana was already plant-like: isolated, merely existing from day to day, offering no emotion and receiving none. Yet by turning Miki into a plant, albeit one that can talk, God—or Asada—is able to give Miki life. He blooms, literally, under Hana's touch, because he is dependent on Hana's care which, in turn, endears him to Hana. Miki was most human, most alive, when he was not human and not entirely alive. A fun twist on the accidental transformation trope.

You can read "A Talking Flower" on Manga Planet (formerly Futekiya).

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello. I found you because of your twitter. So you're also KnB fan? So excited? Are also a shipper? Who are your fav KnB ships?

Can I ask you BL recs that the couples' dynamics remind you of your fav KnB ships?

Sorry if you're not a shipper...Then who are your top 3 fav KnB characters? And what are your top 5 fav moments from the series?

Hello anon! I was and remain a very big KnB fan. I actually have a number of KnB meta posts on my other blog, perhaps most prominently this one on how Kuroko no Basuke is the most romantic manga I've ever read. It is in fact the only fandom for whom I have a dyed-in-wool honest-to-god would-defend-them-to-the-wedding-altar OTP, and that is Kagami/Kuroko. I am always a sucker for main characters in shounen but Kuroko in particular is a guardian angel to me, one with his own guardian angel (Kagami). I find him endlessly fascinating as a character but I also think of him like a beloved nephew and want him to have a happy ending (married to Kagami and raising multiple dogs). I just love him so, so much.

However, I believe in shipping for fun and for sport, not as religion, the result being that I consume(d) voraciously in the fandom even for things outside of my OTP. I loved MidoTaka and bad boyfriends AoKise, would go to war for the Seirin third year Kiyoshi/Hyuuga/Riko (sorry for the sudden het), and was obsessed with KiKasa (legitimately believe Kasamatsu would take a bullet for Kise before he would kiss him and is that not the ultimate romance). Almost every day I wage a battle with myself whether or not to go back and reread the manga or to finally finish the anime (which I maintain legiimately changes the characterization of some of the characters, specifically Kise).

I can't say that I can think of bl manga with the same dynamics as KaKuro. Though I will say I was reminded recently that before Kizu Natsuki was Gusari, she was Sashikizu, and she wrote a pile of KnB doujinshi. While she settled into her sweet spot with Haikyuu, those who accuse "Given" of owing anything to Haikyuu don't see that the central Ritsuka/Mafuyu (+ Hiiragi) story is actually very Kagami and Kuroko coded, Teikou trauma and Generation of Miracles ex-boyfriends and all. Kizu-sensei wrote "Given" for those of us who thought Ogiwara was dead, I'll just leave it at that. (Is that why I later wrote a KaKuro band AU? Who's to say.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

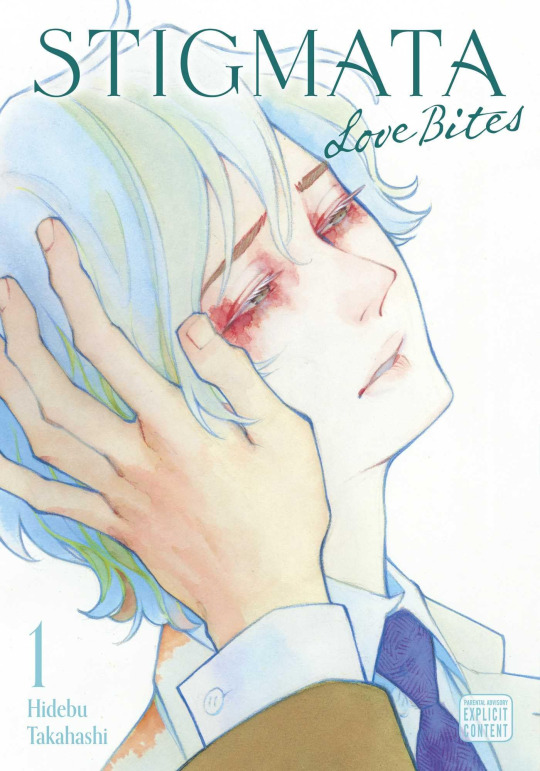

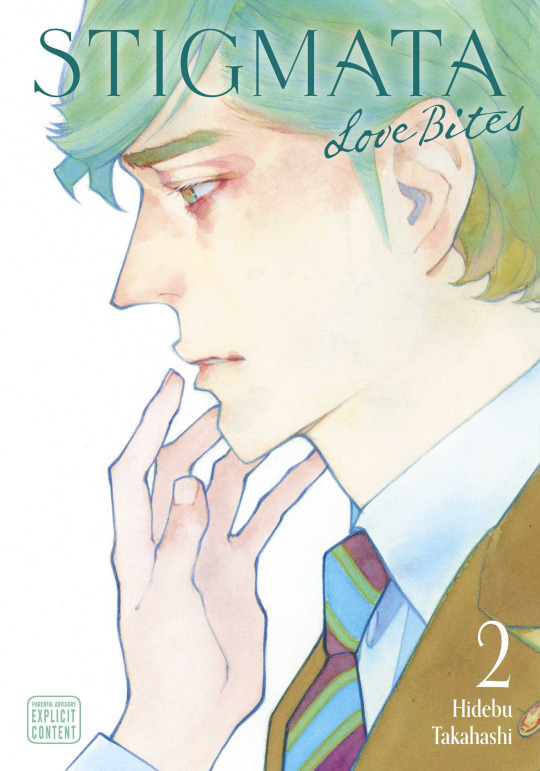

11/50: double vision (takahashi hidebu, "stigmata: love bites")

My favorite euphemism for dating is "seeing someone." No other phrase captures both ends of the romantic spectrum, both the fleeting glance of seeing someone out of the corner of your eye when crossing the street and the intensity of pinning someone with your gaze across a candlelit table. It alone feels capable of holding all of our figurative language about love, from the heavy to the light. Don't we fall for someone simply because we look at them ("love at first sight")? Don't we describe commitment and the monopolizing power of love by saying, we "only have eyes" for another person? We say, "to see her was to love her." We say, "to be loved is to be seen." If "eyes be the window to the soul," then what could sight possibly be but a vector to love?

Lovers aspire to "see" each other, to comprehend each other's souls, to be able to recreate their lover in the mind's eye without masks or pretense. But so too does the forensic profiler, the detective, the criminal investigator. In fact, more so than romance, crime and its fictional iterations lavish excessive time and detail to "seeing." The criminal stalks their victim; the crime scene investigator scours their surroundings for information both on the victim and the perpetrator; the dogged detective is the only person who really understands the mind of the elusive killer. Only the teenage lover left alone in the room of their crush could be more dedicated to trying to see and not disturb, to leave no trace but to take away the wholeness of another person, who is unknown to us now but, we hope, not forever.

No wonder, then, that in these genres we invent new ways of seeing. In NBC's "Hannibal," Will Graham can recreate in his head the events of a murder like a director staging a scene. In Shimizu Reiko's josei crime epic "Himitsu," new technology allows us to image a dead person's brain and see what they saw, as if we were watching a movie filmed through their eyes. And in Takahashi Hidebu's "Stigmata: Love Bites," we follow Asako Minami, who is cursed with the ability to experience the events leading up to and of a murder once he's presented with a murder scene. It's an ability that has ostracized him from family and friends, but with the help of his supervisor Kuroiwa, the senior detective of Tokyo's Special Investigations Unit 6, his body is a conduit for solving crimes, including the murder of Kuroiwa's ex-wife Mari.

"Love Bites" is actually the second draft of a story starring Asako and Kuroiwa. Takahashi first ran "Stigmata" (then subtitled Seikon Sousa, or Stigmata Investigation) as a seinen crime-of-the-week series in Shueisha's Grand Jump Magazine before it was canceled at six chapters. "Love Bites", the reboot, ran in the bl magazine Bloom, which would later also run Takahashi's other supernatural detective story "Psychedelia." Maybe that's why "Love Bites" has an atypical structure for a bl; instead of one long story that concludes with its characters more or less together in volume one and a pivot to a different subplot in volume two, it's more like a ten-episode miniseries that uses the full two volume length to explore the mystery of who killed Mari.

Freed of having to mimic the rhythms of a procedural, or perhaps cognizant that as a bl her story must now make feelings the plot instead of murder, Takahashi fills "Love Bites" with figurative language made into images, all the artistic trappings she has at her disposal. Blood bubbles out of Asako like a furious lava lamp, splattering against the floor and white backgrounds in endless dots and dribbles, a Van Gogh-ian nightmare. His dreams, where he is forced by Mari's memories to ride shotgun to her intimate moments with Kuroiwa, are haunted by the same big blobs, as if they and the blood bubble out of the same place. When Kuroiwa begins to fall for Asako in volume two, he too begins to sink into panels full of alternating blobby darkness and bubbling white. The illusion "Love Bites" traps us in is a sticky, liquid, fractal place, the boundary between reality and the supernatural. We cannot and should not believe our eyes. What we see cannot be happening. And yet, what we see is the truth.

What "Love Bites" contemplates (as does "Hannibal" and "Himitsu") is that there are two types of "seeing." To see someone is to understand them and, perhaps, to love them. To see as someone, though, is a special kind of emotional abomination. It is a transgression, an intimacy that is both more and less than love. In "Himitsu," seeing through the eyes of Kainuma, the serial killer who killed out of his love and longing for Maki, ruins Suzuki life. The curse is compounded when Aoki, already drawn to Maki, watches Suzuki's brain and is hit with the double whammy of seeing Maki through both Suzuki, and Suzuki-Kainuma's eyes. Doomed to be a Suzuki substitute from the start and now the living embodiment of Suzuki's memory, he is Eve and the apple both. Unable to resist, Suzuki takes from the Tree of Knowledge—Suzuki's brain—and then spends the rest of the story posing the same poisonous question to those who loved Suzuki. When we crawl into someone else's skin, can we ever come back from it? Or have we been forever poisoned by their visions?

These questions must have plagued Takahashi too. In "Stigmata," Asako struggles with how to maintain a sense of self when he is a repository for the memories of other people. In a particularly heartbreaking scene, he asks Kuroiwa if he should just let Mari's memories take him over. "Then, won't I basically be her on the inside? That means you'll get a chance to do things over with her." Aoki and Asako would have lots to say, I'm sure, if they were ever to meet for coffee.

But I think the theme of "Love Bites" is false visions, or rather, incomplete ones. Mari is mistaken multiple times for her coworker Makoto. Kuroiwa at the end of volume one embraces Asako and calls out Mari's name. Asako's body is female, then male, then female again in his dreams as he tries to digest the murder victims for whom he is a conduit. Even seeing through one person's eyes, Takahashi argues, can never be the whole truth. After all, in Kuroiwa's eyes, Mari had fallen out of love with him and thus ended their marriage. Asako, haunted by Mari's echoes, believes that Mari loved Kuroiwa even to her dying moment. But it's Makoto who fills in the missing piece that neither Asako nor Kuroiwa would have gotten to. Mari may have loved Kuroiwa, but she kept that love like a talisman, a prayer for better times, not a longing to return. She most of all would have never wanted to live on in Asako's body, as a zombie of the relationship she and Kuroiwa once had.

Asako may have had Mari's echoes, but I think what made Kuroiwa fall in love was all the ways in which he wasn't like Mari. He is not a cheery go-getter. He is not a competent career woman. He wants to be a burden on Kuroiwa. His helplessness, his desperation, and his offering up of his body as the only tool at his disposal are the things that make him precious to Kuroiwa. No matter how much he may be filled with Mari's memories, it is the realness of Asako and Asako alone that Kuroiwa reaches out for.

"Stigmata: Love Bites" is available to read on Manga Planet (formerly Futekiya). You can also read "Psychedelia" there; it's a one-volume story that also is about supernatural crime solving, and as an added bonus appears to be set during the pandemic (all characters featured wearing facemasks). "Stigmata: Love Bites" is also available in print or digitally from SuBLime.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

So ever since I found mlm and wlw stories (especially fanfics and BL & GL media), my interest in het romance decrese a lot, and what I search for is just the dynamic between mc (male) and male lead or mc (female) and female lead...

I don't want to read mc (female) and male lead or mc (male) and female lead...And what I want to read mostly are just mlm or wlw stories for romance....

What do you think is happening to me? Is it really weird?

This ask immediately caught my eye and I have been struggling on and off this weekend with how I should answer this.

So first. "Is it really weird?" No! It is not weird at all, and don't listen to anyone who is telling you it's weird. I don't really believe in pathologizing our tastes in media (except in extreme cases, and this is not an extreme case).

Ok, that's the easy part. "What do you think is happening to me?" Anon, I don't know you, and I don't know your personal circumstances, so I can only answer this in generalities and from my own personal experiences. If I make assumptions and they are wrong, please understand that I do so not from a place of malice or condescension, but simply from a place of unknowing. I am the blindfolded man in a room with an elephant, tugging on its tail and saying "this is a snake."

Any number of things, all totally normal, could be happening to you. You could just be drawn to certain tropes or plots or character dynamics that are very common right now in certain bl/gl media or fanfics but less common in m/f romances, or at least the ones that are popular now. Finding things to enjoy takes time and curation and often, too, curating where you get your recommendations.

Or, you could just be really excited about the fandoms you've discovered through bl/gl media or the canons you're reading fanfic in. A lot of bl/gl media have welcoming and exuberant fandoms where it's easy to meet friends who share your tastes! And to the point about curation, the more friends you make, the more you'll get tailored recommendations from them, which means the more bl/gl media you'll have to consume. Heaven knows my to-read pile grew exponentially since I came back to this tumblr.

Or, you could be learning more about yourself in these bl/gl stories. I think being drawn to bl/gl media (and fanfic starring mlm/wlw romances) is a very common way for many queer/not-straight people to explore their own sexualities. We often use fiction as a way to imagine ourselves in other lives and to grapple with how these alternate lives make us feel, if there are new modes of self-expression we aspire to, whether fictional characters are putting in words feelings we didn't realize we had. Even as a straight and very cis woman, I find reading bl/gl helps me articulate certain conceptions of what relationship should be and the pressures we face from society with respect to growing old, having community, raising children, etc. A better life is possible, and fiction helps us dream it into being.

Ultimately, I think there is no harm in following your heart and reading more of what you like. But I also do believe good het romances and m/f relationships and friendships are out there (LMAO what a sentence). You may just need to invest some time in pinpointing what it is you like in your fave m/m or f/f relationships and searching out those things in non-bl/gl media! For example, in my case, I love detectives, crime procedurals, and odd couples forced to be coworkers. Usually, this leads me down m/m paths (like, say, "Beyond Evil"), but the minute I saw the plot summary for "The Bridge (2011)" I knew it would be catnip for me, and indeed the friendship between the two lead detectives in the first two seasons of the show (one male, one female) remains hands down one of my favorite pieces of fiction.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

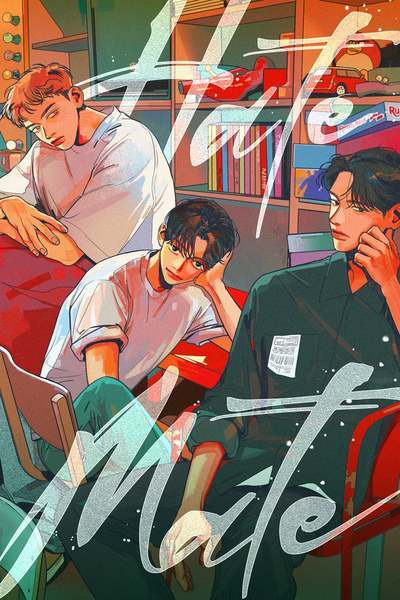

10/50: be sweet to me (reck/yeongha, "hate mate")

It's another week where I come to you not with a rec but with a meditation on (what else?) love and, specifically, the conundrum of being loved by a yearner.

There was a tweet going around that was like, "everyone person in bl fandom has that one bl that is their brand and reminds everyone of them." Well, I have always been a contrarian and all my friends who have known me for a long time in fannish spaces have accused me of hating love and/or happiness. But if you asked, they could all name the one dynamic that gets me every time: the not quite love triangle where character A and B are in a relationship that is actually about A or B's feelings for character C. This is why I am always game for a story where a man who has been in hopeless unrequited love for a long time suddenly finds himself being pursued by a stranger, or when a main character, who is in a relationship, is forced to confront an ex with whom he still has unresolved feelings.

So in a way, "Hate Mate" was written specifically to target me.

(This post will have spoilers for the entirety of Hate Mate.)

Bang Subin has been in love with his best friend Nam Hyeonwoo since high school. Buoyed by a night of drinking and Hyeonwoo's return from his two-year military stint, Subin manages to finally talk Hyeonwoo into sleeping with him, only for Hyeonwoo the next morning to deny anything ever happened and reveal that he has had a long-time crush on Subin's boss, a beautiful older woman named Yeona. Increasingly uncomfortable in the apartment he shares with Hyeonwoo and sick of seeing Hyeonwoo try to woo Yeona (who wants nothing to do with dating a young man), Subin turns to Kang Jun, an older salaryman Subin met on a gay dating site. Though put off by Subin's immaturity and the fact that Subin is obviously using Jun to get over Hyeonwoo, Jun finds himself first trapped and then reluctantly drawn into caring for Subin. Hyeonwoo, meanwhile, is forced by Yeona's repeated rejections to confront his own feelings for Subin, eventually coming to the realization that he does wants to be with him. Too little too late, however, as Subin has decided to close the book on his long-time crush on Hyeonwoo for a new relationship with Jun. Though they are not quite happily ever after, they move in together, and Hyeonwoo leaves Korea for a music career in Los Angeles so that he never has to see Subin and Jun together again.

Never, that is, until two years later when Hyeonwoo comes back to Seoul for "Hate Mate" season two.

You know I am hard on first loves and first men and generally find any story of "we met when we were younger and now we are destined to be together" to be, by default, suspect. But what is there to love about Nam Hyeonwoo? We consider him a love interest at first because Subin loves him and envies his talent and allows Hyeonwoo to make him miserable. We consider him a love interest later in S1 and throughout S2 because he tells us he loves Subin. But his actions are that he ignores Subin for years, repeatedly rejects Subin's feelings, lies to him about a drunken sexual encounter, interferes in Subin's life despite claiming to be in love with another person (woman), and then goes back to ghosting Subin for two-year periods. The one moment of kindness he shows (going to pick up Subin with an umbrella on a rainy day) is derailed by him ditching Subin for Yeona. The depths of Hyeonwoo's feelings are entirely in his head to which we, the readers, are given full access, but no one else.

The problem with Nam Hyeonwoo is the problem with any story that stars the yearning man as a love interest. Yearning is not, by itself, love. Yearning is the twin of limerence, the destructive sibling of self-soothing, an outpouring of emotion within ourselves, for ourselves. It is, in some ways, a delusion that happens entirely in our heads. It is not a relationship we have with the other person. The other person is simply an object.

Yearners survive in art because they write poems and draw portraits, because they model plays and novels on their affections, because they leave behind letters and journals. This is, of course, why Hyeonwoo is a musician and why "Hate Mate" S2 features music he has made about his feelings for Subin. But this is yet another way in which the object perfects the yearner's life, as opposed to a way for the yearner to engage the object. High school Subin was very important to Hyeonwoo, in fact maybe the only thing that mattered to Hyeonwoo after his parents died. But what does that matter now to 23-year-old Subin, or 28-year-old Subin? What can Hyeonwoo offer for Subin, instead of merely at him? Can love be judged just on depth of emotion? Is love just who cares the most in their head?

If all we craved was to see one man say in words that they love another man, then bl as a genre would be enough. So why, then, do we keep turning to shounen manga and insisting there are deep, loving m/m relationships hidden in plain sight? I think it's because male characters in shounen manga are always doing things to or for or at another male character, and that feels like love. If they yearn, they cannot do so purely emotionally, because it is a genre that by and large rejects pure emotion between men. So instead, they become better rivals or students or mentors or partners; they grapple with each other physically; they fist bump or strangle or punch or high five each other; they connect.

Subin has loved Hyeonwoo for years too, but he is a different kind of desperate bl man: the orbiter of unrequited love, who does anything he can to keep himself close to the object of his affection. So he learns to cook for Hyeonwoo, he takes care of Hyeonwoo when he is sick, he learns guitar and works at Hyeonwoo's old workplace to remain close to Hyeonwoo's passions, he tests Hyeonwoo's affections over and over again even though he knows where he falls on the list. Is it any surprise, then, that Subin ends up with Jun, whose biggest fault was simply committing to a half-hearted affection too quickly?

Which is to say, there could have been no other ending for "Hate Mate" except Subin choosing Jun. Jun's view of love is punishingly rational, practical, productive. In a relationship, he puts in effort, for which he is rewarded. He compares it to studying, where effort results in good grades; Subin compares his approach to cooking, which (usually) produces food. For Subin, who spent seven years longing for a man who gave him nothing, this is a revelation. Through his time with Jun, Subin is incontrovertibly changed, though he (and perhaps Reck and Yeongha) does not fully comprehend it. When Subin rejects Hyeonwoo in S2, he says, "I would fantasize about you being in love with me. I'd imagine you regretting the way you treated me and begging me to forgive you in anguish." But all that imagining, all that fantasizing, it is over now. All Hyeonwoo can offer Subin are reflections on their past together, and Subin at 28 becomes a person who values work and effort over feeling. Love or the absence of it does not live in only in his head. He makes curry for Hyeonwoo and tends to Hyeonwoo's body one last time. He cannot do that for Hyeonwoo again, because those actions are the vectors through which love moves, and vectors should be a two-way street.