Text

Cyborgs, “Emotion Picture,” and Robot Futures

If this is the last of our blog posts for ETHN 115, considering there aren’t any more readings left, I will be glad that I got to talk about Janelle Monae and her “Emotion Picture” in the very last one. Ever since a friend introduced me, about a year ago, to her life, her work, and its meaning, I have been in awe with her ability to create entire worlds with her artwork, something that is on full display in the “Emotion Picture” for her album Dirty Computer. She engages with Afrofuturistic thought as a way to reclaim modernity and technology for those who have commonly be left out of it. When I say this, I am thinking about corporations which preach “progress” when their technological development comes via the exploitation of specific communities, and I think of a booming tech industry that is dominated by men, among other examples. I have often struggled with the violence that these notions of “progress” tend to perpetuate in the world, which is why it is so beautiful for me to see Afrofuturism at work, because I see worlds where technology does not come at the expense of anyone, and if anything, it is used to uplift those who have been pushed to the margins, something I see as a commonality in the visions of both Janelle Monae and Donna Haraway.

The title of the album, Dirty Computer, was the first term that got me thinking about what her songs and the film meant with respect to her own identity and experience. In the main scene we see Monae herself as the target of an intentional erasure of identity and lived experience, because she, because of her Blackness, her womanhood, her sexuality, etc. has been deemed “dirty.” She struggles to express her true identity when under the constant surveillance of a system which refuses to allow her existence. These dystopian aspects of the world Monae creates put us, as the viewers, in a place of empathy (hopefully), where we see a symbol of what her experience might look like in a world that has attempted to teach her that her life doesn’t belong.

At the center of Monae’s message seems to be a defiant reclamation of her agency. This agency is at times focused on the sexual, as seen and heard in “Screwed,” and it can also simultaneously allude to the (haunted) power dynamics that she has experienced, as evidenced in “Django Jane” when she talks about “(speaking) truth to power,” and refusing the patriarchy, “Let the vagina have a monologue, Mansplaining I fold ‘em like origami ... ” (I also just want to point out the incredible power in her lyricism and visuals in all aspects of her work, because as I type this up I realize I am quoting her lyrics from memory and each line is conjuring up the visuals from her videos, like the mirror placed on her vagina during this second line).

In Monae’s work, the orphaned beginnings seem to be a starting point from which we understand her experiences. She talks about her upbringing in “Django Jane,” having grown up with a father working hotels, her mom driving for a living, and her working in retail to make ends meet, and these stories serve as a platform for understanding and appreciating her incredible accomplishments as an individual, an artist, and much more. She also mentions the ways in which she has been seen as “other” or “monster.” I especially think of the line “remember when they used to say I looked too mannish?” likely an allusion to the trope of questioning the womanhood of queer women of color. The creation of the character of “android” which defined a previous album and continues into her work in Dirty Computer is essentially an embodiment of this “other,” this “monster” character which she identifies with because of all the ways she has been treated as an outsider.

Perhaps the greatest triumph of Janelle Monae’s work, however, possibly applicable to Donna Haraway as well, is that she is able to create a world that functions outside of this place of trauma. Sure, the entire world and its characters are built upon certain experiences that are inseparable from the oppression that she has faced as a Black queer woman. At the same time, this world is one of imagination and hope, which is why I think it is the perfect example for our “Robot Futures” unit. The character of android, and the notion of this Afrofuturistic, politically powerful, highly accoladed, sexually liberated woman is so incredibly powerful, yet at its core it is a simple concept: a world that uplifts someone like Janelle Monae for everything she ALREADY is.

0 notes

Text

Week 8 Glossary Entry

“Dirty”

This goes in line with Professor Espiritu’s concept of differential inclusion, which explains that any group that is considered “foreign” or “outsider” to the United States and yet is present in its makeup has been brought here to serve the nation-state a specific purpose. If I had to write from my heart and not as an academic, I’d say it plainly: They want our services but not us. They keep us at an arm’s distance as if we’re “dirty” and we don’t belong, and that’s essentially how I’ve felt here my whole life. But I also know I’m not dirty, I’m just complex, and I belong just as much as anyone else.

0 notes

Photo

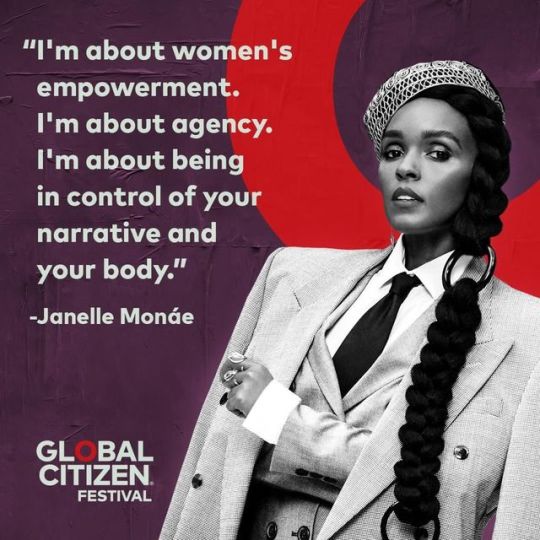

‘Cause we got the #PYNK! Can’t wait to see you this weekend in Central Park @janellemonae 💕 Have questions about Saturday’s Global Citizen Festival? Check out the FAQs here.

20 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I would argue that specific forms of families dialectically relate to forms of capital and to its political and cultural concomitants. Although lived problematically and unequally, ideal forms of these families might be schematized as (1) the patriarchal nuclear family, structured by the dichotomy between public and private and accompanied by the white bourgeois ideology of separate spheres and

nineteenth-century Anglo-American bourgeois feminism; (2) the modern family mediated (or enforced) by the welfare state and institutions like the family wage, with a flowering of a-feminist

heterosexual ideologies, including their radical versions represented in Greenwich Village around the First World War; and (3) the 'family' of the homework economy with its oxymoronic structure of women-headed households and its explosion of feminisms and the paradoxical intensification and erosion of gender itself.

Donna Haraway in “A Cyborg Manifesto”

0 notes

Text

Glossary of Haunting Week 7 Entry

“Social Justice”

This term has played such an interesting role in my life because of the spaces and contexts in which I have heard it. There are so many aspects of this work that many of us have taken some part in, and I have often had to steer away from the actual term “social justice” because of some of the stigmas I have seen around it. Instead, I prioritize the intentions and the material impacts of work because at the end of the day, I think this work is about loving human beings and helping members of our communities achieve the outcomes they deserve, which have been kept from them. As I recognize my time in the “academic bubble” is ending, I think more and more about how sometimes our conversations deviate so far from their intended purpose, and I try to prioritize keeping things simple, accessible, and sustainable.

0 notes

Text

“My Story Isn’t Over Yet;”

Dear mom,

You are the strongest, most understandable, beautiful, caring, helpful, genuine, loving, and supportive woman i have ever met. You are truly a blessing from god. These past six months have been tough, but you have never given up on me, and I am eternally grateful for that. Today you got me this ring. This ring is a symbol that will forever be close to my heart. With this ring, today, I “officially” promise to stay alive for you. Thank you for being the best support system in the entire world. i love you. (comment some love down below for your own mama/ guardian/ loving support systems. they deserve it. 💓)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Disability Justice” and Love as Truly Transformative and Revolutionary

As the end of my last quarter nears and my mind moves towards a place of understanding life simply for what it is, and how it exists outside these academic spaces which have played a significant role in my development over the last few years, I think more and more about how social justice work is actually creating the world that we and our communities want to see. One thing that a peer recently said that hit home was the idea that everything we’ve learned, especially in majors like Ethnic Studies and Sociology which attempt to create discourses and praxes to drive societal change, is simply academic jargon for more innately human behaviors like empathy and love.

When I see the field of disability justice and the ways it has spearheaded the imagination of a world that acknowledges all human beings as differently abled, and which accommodates human beings regardless of what these abilities may be for a given individual, I think the connections between this field and “love” are inherently present. Mingus stresses that transformative justice does not end at increasing access that currently does not exist, but rather transcends this goal, and involves creating a world where no group or ability can ever be pushed to the margins as “other.” Disability justice is love for every human being, to the point where we care to build a world where everyone can participate.

For these reasons, I was especially appreciative of how Mia Mingus brings up the idea of “accessing intimacy.” If we are about creating a world for everyone, CENTERING those who are most marginalized, we should do this with the intention not only of alleviating material disparities which we know to exist, but also with the intention of creating spaces where folks who are differently abled are allowed to exist as human, free of the pressures and anxieties that arise from being perceived and treated as “other.”

In our current world, we see those whose abilities are treated as “different” or “deviant” as both monsters and orphans. They are orphans because they are born into a world which, for no valid reason, treats them as “other” and puts certain burdens on them, including a lack of support, which human beings whose abilities are prioritized in this capitalist world that also does the work of disabling certain populations. They are monsters because they are often kept at the door, outside spaces which should exist to include them. Often times, this can even include spaces which they themselves created. I’ve learned a lot about how the history of organizing is inseparable from struggles for disability justice, and yet the physical labor which is prioritized in some, if not most organizing, is often ableist and inaccessible for many.

Yet we see robot futures in the possibilities we imagine keeping in mind love and intimacy. Rather than allowing institutions which are historically built to define “other” to control our understanding of human interaction and love and support, we can take it upon ourselves to build networks, spaces, and communities which prioritize the human being, and I believe that this idea is at the very center of Mia Mingus’ discourse on “Disability Justice.”

0 notes

Quote

When I started out doing disability justice work, before it was even called “disability justice,” these spaces were so rare. I want people to not take this space for granted because so many disabled people would kill to be here and so many people don’t have access to this type of space. And I know that for a lot of us, this I our political work, this is our life and we seek out these spaces, we create them. When I started out doing disability justice work, before it was even called “disability justice,” these spaces were so rare. I want people to not take this space for granted because so many disabled people would kill to be here and so many people don’t have access to this type of space. And I know that for a lot of us, this I our political work, this is our life and we seek out these spaces, we create them.

“‘Disability Justice’ is Simply Another Term for Love” by Mia Mingus

0 notes

Text

Infiltrated Intimacies

In this week’s reading, we receive firsthand narratives regarding the violence of displacement, and the realities of how this looked for Palestinian peoples who experienced the exodus. Specifically, feminist scholarship is critical in understanding the nature of the oppression of Palestinian people given the gendering of the experiences of colonialism which have affected this population.

As we discussed in class, settler-colonialism is inherently dependent on the the exploitation of the bodies of womxn and the reproductive labor that is expected of those who are not men, so these narratives are at the center of understanding how this imperialist, settler-colonial project of the Zionist state has been experienced by the Palestinian communities it has displaced.

Haunted power dynamics exist in the very nature of settler-colonialism, given that the majority of conversation regarding this region is centered around the stories of displaced Jewish peoples and the violences they have endured, yet the stories and traumas of the Palestinian people are consistently erased. This is the intentional design of a power dynamic which privileges the settler group.

The haunting is evident not primarily in the stories that HAVE been told about the Palestinian people, but in those that have been kept in because they’re so intensely traumatic that some Palestinians would prefer they remain buried, much like the notion of monsters that live on the margins but are never fully forgotten or pushed out. So too, the nation of Palestine may have much of its history erased, and its oppression ignored, but it is never forgotten.

The concept of “infiltrated intimacies” is possibly most applicable to the concept of orphaned beginnings. In this work Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian talks about how the literal acts of childbirth and child rearing were subjects of the process of colonization. She tells stories of Palestinian refugees struggling to sustain their children, given the economic realities of their displacement. This struggle of child rearing becomes both the site of violence and the site of survivance, given that this act/process, while a target of the Zionist violence, is also a cornerstone to the protection of Nakba heritage and tradition, “Again, the milk of the mother’s breast becomes a focal point in the remembrance of the Nakba experience.”

0 notes

Text

Glossary of Haunting Week 6

“woke”

I feel a little confused that I have to put this on here and write my thoughts about what passes for “woke.” But amidst the culture of shaming activists for being “social justice warriors” or “keyboard warriors” (even those of us who are doing much more than that) and using the word “woke” sarcastically, we actually have white, settler-colonial states which expand their imperialist projects by claiming to be the saviors against anti-LGBTQ, misogynist, and “Anti-Semitic” practices. The entire point of Canary Mission, for example, is to build support for Zionism and Israel by claiming that recognition for Palestine and its people IS the same thing as Anti-Semitism, and putting the threat of law enforcement behind this mission.

0 notes

Quote

Although these stories of familial betrayal, psychological terror,

and the manipulation of girls’ sexuality speak to the profound aftereffects of violence, the greatest impact of the scale of Israeli violence

can be registered in the decision of many Palestinians not to speak of it

at all. The humiliation, agony, and betrayals that Palestinians endured

were often not shared with future generations. Wardeh never spoke with

her new family about the three children and husband she left behind

when she returned home. The stories of sisters left behind in the mud, or

daughters surrendered to the authorities, although common experiences,

were seldom voiced to future generations.

“Infiltrated Intimacies” by Nadera Shaloub-Kevorkian

0 notes

Text

The War on Terrorism

Dominant narratives of history, the type that most students, at least those of my generation, have been exposed to throughout our upbringing, through the school system in the US and much of the media we have consumed, construct the image of the “terrorist-monster” that Jasbir K. Puar and Amit Rai talk about in this week’s reading. Given the amount of social construction that has taken place, especially post-9/11, there are entire false narratives that have become commonplace in discussions regarding the “Muslim terrorist” trope.

One thing that Puar and Rai analyze is the way the psyche of this character is portrayed as something which is racialized, with a very relevant example being the myth of a sexually frustrated Muslim man who will be granted an abundance of virgins as a reward for carrying out a violent jihad. It is important to note, in this conversation, that the Western conception of the jihad is very much a falsified version of its true meaning in Islam, also constructed as a part of this myth.

Orphaned beginnings are evident in the lives of those who are Muslim and queer, as bodies who have been incorporated, to some extent, into this nation-state, and whose experiences have been adapted towards the agenda of Western and American exceptionalism. For example, Puar and Rai make references to the process of pink-washing, and other “savior” complexes of the United States which have been used to justify imperialist advances. In order to justify its violence in the Middle East, the US has employed a savior complex by citing violence against women and LGBTQ communities in the region, creating from these forms of oppression a monolith of those societies that has allowed the US to claim itself the savior to the liberation of the women and queer folks who inhabit those communities.

Monstrous presents exist in the communities of Muslim folks living in the United States, and those abroad, whose experiences have become the “other” through this construction of the “terrorist-monster” character. On the surface, this trope of the terrorist has been painted in a very simplistic light (i.e. killing people is bad, and law enforcement has been employed to prevent these dangers). The “monster” is kept outside the door via the non-explicit racialization of this character. He has been propagandized as a brown Muslim man, at odds with the unity of the people of the United States, and as the justification for the United State’s exploits into the Middle East.

If there is a message for hope that is evident in this story, to imagine robot futures from within the realities of US imperialism and the marginalized identities which the US has constituted as the “monsters,” it is that these constructions have become so reliant on these fragile constructions of Muslim societies and queer folks that the simple act of presenting counter-narratives which shatter these notions may very well do the work of allowing oppressed people to imagine a nation-state where we get to define our own communities.

0 notes

Text

Glossary of Haunting Week 5 Entry

“Normal”

Growing up in the United States I had many ideas pushed on me regarding what the world “normal” meant. A lot of ideas that scratch the surface of race, gender, and sexuality, are conceptions that we address in academic/social justice spaces, like heteronormativity, patriarchy, and white privilege. However, given the excessive influence that white, cishet men have over knowledge production, I’m surprised that I keep finding new ways that this concept of “normal” has been pushed on me, even though what it has served to accomplish is essentially make someone with these “deviant” identities feel crazy for simply existing. Jasbir Puar’s conversation regarding the racialization of the psyche of the “terrorist” trope is the perfect example, where myths like “Muslim terrorists are awarded seventy virgins for carrying out a jihad” (noting that even Western conceptions of jihad are extremely flawed for the very purpose of being adaptable to the white man’s myth) are perpetuated simply to erase the humanity of those who fall into these “deviant” categories so they can be scapegoated for the benefit of the nation-state.

0 notes

Quote

What all these models and theories aim to show is how an otherwise

normal individual becomes a murderous terrorist, and that process time and again is tied to the failure of the normal(ized) psyche. Indeed, an implicit but foundational supposition structures this entire discourse: the very notion of the normal psyche, which is in fact part of the West’s own heterosexual family romance—a narrative space that relies on the normalized, even if perverse, domestic space of desire supposedly common inthe West. Terrorism, in this discourse, is a symptom of the deviant psyche, the psyche gone awry, or the failed psyche; the terrorist enters this discourse as an absolute violation. So when Billy Collins (the 2001 poet laureate) asserted on National Public Radio immediately after September 11: “Now the U.S. has lost its virginity,” he was underscoring this fraught relationship between (hetero)sexuality, normality, the nation, and the violations of terrorism.

Jasbir K. Puar, Amit Rai in "Monster, Terrorist, F**: The War on Terrorism and the Production of Docile Patriots”

0 notes

Text

Why do we try to explain gender?

Oyeronke Oyewumi pertains to many critical concepts in overall discussions of justice, specifically as they pertain to studies of the experiences of women of color. Perhaps one of the most critical conversations that comes out of this work, however, is a critique of colonialism, its preference of Western thought, and the notions of universality that come out of these western practices. The academic notion that there is a means of, or even a need to, apply some kind of universal framework to the experiences of ALL marginalized by gendered injustices runs counter to the specificity of gendered experiences in any single community or culture, and by centering narratives of the Yoruba society, Oyewumi calls attention to the failures of Western thought to address these experiences in a productive way.

One of the interesting critiques which Oyewumi mentions in her preface is the critique of this notion:

“Gender is a fundamental organizing principle in all societies and is therefore always salient. In any given society, gender is everywhere.”

It is important to understand that while Western teachings, and as a result, even teachings which attempt counter Western thought, engage with topics of gender and sexuality, given the material impacts that they have on members of our communities, this is not to say that gender as we know it is a necessary pillar of society, and one that societies have always needed to recognize in order to exist and function. In fact, the concepts of gender and sexuality which we recognize academically today were those brought by white colonizers, which disrupted our societies in dramatic and violent ways, so my understanding of liberation for my own community exists outside of any definitions pushed on us by this colonial way of thinking.

We see a very specific example of this in the second reading for this week by Wairimu˜ Ngaru˜iya Njambi which discusses the failures of Western feminist thought. Njambi talks about the practice of irua ria atumia, a practice which has come to be known in the West as “female genital mutilation” and viewed as evidence of the existence of the oppression and subordination of women in an ethnic group in Kenya who engage in this practice. The irony of this reductive label is that this practice of Gikuyu women has actually been viewed within their culture as a symbol of agency and possibility for women in this anti-colonial struggle.

In a sense, the attempts of the West to be “woke” have actually simply perpetuated the false logic of Western exceptionalism because researchers saw people in these communities as research subjects before they saw them as human beings. Oyewumi’s research is therefore necessary, in a very human sense, because she recognizes the idea that people from these various communities have very different experiences that cannot and should not be encapsulated in a single theory, especially when these theories are created without being in conversation with these communities, and without an active refusal of Western thought and the violences it perpetuates in upholding the ideals of the colonizer.

3 notes

·

View notes