All You Need to Know About Japanese, Brought to you by Bungou Stray Dogs! Please feel free to interact and ask questions!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Omake 4: Ability

((I’ve been so busy recently...but never fear, I shall continue to update~!)) Today’s Omake is very short: the word for Ability!

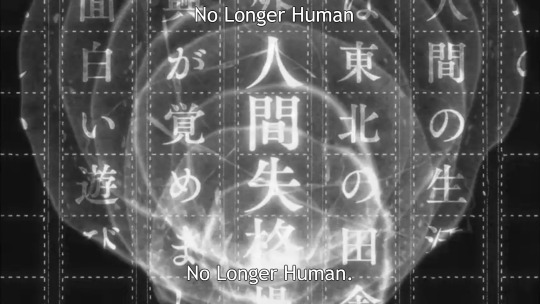

能力 のうりょく nouryoku 能 means ability, talent, skill 力 means power

This word can be used for any sort of commonplace ability. But wait! Ability Users actually use the word:

異能力 いのうりょく inouryoku Which more closely means unusual ability, supernatural ability, or ability beyond that of normal humans!

異 means unusual 異能 いのう inou also means unusual power or superpower!

Kunikida-san and Atsushi-san use both these words when Kunikida-san talks to him about the ADA~! \( ̄▽ ̄)/

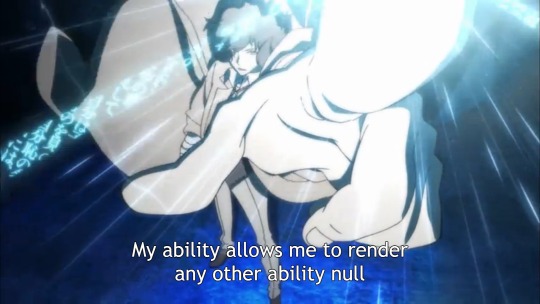

And Dazai-san uses inouryoku in his fight with Atsushi-san! Listen for it~! Ganbatte~ (๑˃ᴗ˂)ﻭ

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 2: Verbs of Existence: Iru/Aru

Sorry about the delay, Fukuzawa-shachou has decided I need to start school, so I’ve been a bit busy (〃>_<;〃)

Anyway, time for Lesson 2! In this lesson, we’ll learn to say that people and things exist, ask where people and things are, and learn how to say you have something. We’ll also cover some words of location and continue the Ko-So-A series for locations.

あ、太宰さんがいます。Ah, Dazai-san is here. Of course, he’s not really working….(;⌣̀_⌣́)

Iru/Aru. A wa B ni imasu.

In Japanese, there are two basic verbs of existence, or ‘to be’. One for inanimate objects and plants: ある aru (Dictionary/Plain form) あります arimasu (Polite)

and one for living things (besides plants): いる iru います imasu

This pair of existence verbs (iru/aru) are used both to say that: 1) something exists/something is there 2) somebody owns something, has something

For example:

When I arrive at the Agency in the morning, and I open the door and I see Dazai-san (which is strange, because he’s rarely here in the morning), I think to myself: あ、太宰さんがいます。 あ、だざいさんがいます。 A, Dazai-san ga imasu. Lit. Ah, Dazai-san exists. Or, more colloquially, “Ah, Dazai-san is here.” (‘Here’ isn’t specifically stated, but it’s understood.)

Now, what if I want to specify the location someone is in? Let’s say Dazai-san asks me where Atsushi-san is: 鏡花ちゃん、敦君はどこですか。 きょうかちゃん、あつしくんはどこですか。 Kyouka-chan, Atsushi-kun wa doko desu ka?

‘Doko’ means ‘where’, as in where is a thing, where is a person.

And if you remember Lesson 1, ‘desu’ is the polite sentence ending when you aren’t using another verb at the end. Dazai-san could casually say “Atsushi-kun wa doko?”

Key Point: “Where is ____?” = “____ wa doko desu ka?”

So, because I saw Atsushi-san in the first floor café on the way in, I’d then respond to Dazai-san: 敦さんはカフェにいます。 あつしさんはカフェにいます。 Atsushi-san wa kafe ni imasu. Lit: As for Atsushi-san, he is located in the café./Atsushi-san exists in the café. Or: Atsushi-san is in the café.

敦さんはカフェにいます。 Atsushi-san is in the café.

I can also simply say: Kafe ni imasu.

Since it’s obvious we are talking about Atsushi-san, so I don’t need to specify the subject again.

Key Point: “Person A is located/exists/is in location B.” = “A wa B ni imasu.” Or: “B ni imasu.” if the subject is already understood.

Japanese grammar is rather flexible, so I can also exchange the two pieces of the sentence and say: Kafe ni Atsushi-san ga imasu. Lit. In the café, Atsushi-san exists. In the café is Atsushi-san.

‘Ga’ is more commonly used in this structure than ‘wa’.

Key Point: “In location B is Person A.” = “B ni A ga imasu.”

no•の connector and location words:

The 2 patterns above can be used for inanimate objects if aru is used instead!! Dazai: 私の本はどこですか。 わたしのほんはどこですか。 Watashi no hon wa doko desu ka? Where is my book?

Me: 太宰さんの本はカフェのテーブルの上にあります。 だざいさんのほんはカフェのテーブルのうえにあります。 Dazai-san no hon wa café no teeburu no ue ni arimasu. Lit. Dazai-san’s book is located on the table in the café. Or: Your book is on the table in the café.

Oh my gosh, what’s going on? What happened to my A wa B ni arimasu structure??? Answer: It’s still there! But now we’re giving a relative location of the book, on the table.

On the table: Teeburu no ue.

In order to give relative locations such as: on top of, under, next to, in front of, etc, we connect the relative locations words to the objects they refer to using the connection particle の ‘no’. ‘no’ can also be thought of as: ‘s (apostrophe s)

Here is a list of relative location words:

上•うえ• ue• on top, above 下•した • shita• under 近く• ちかく• chikaku• nearby 隣• となり• tonari• next to 前• まえ• mae• in front of 中•なか • naka• inside 後ろ• うしろ• ushiro• back, behind (of people, buildings, etc)

So we can say:

on top of the table: teeburu no ue under the table: teeburu no shita near the table: teeburu no chikaku next to the table: teeburu no tonari in front of the table: teeburu no mae inside the table!?: teeburu no naka (maybe the table has a drawer or something….) behind the table: teeburu no ushiro

Hon wa teeburu no ue ni arimasu. The book is on the table. (A wa B ni arimasu.)

To say that the table is in the café, we also use the connection particle ‘no’.

kafe no teeburu lit. The café’s table. The table in the café

Connecting the two sentence pieces, we have:

Hon wa kafe no teeburu no ue ni arimasu. Lit. As for the book, it’s on the café’s table’s top. Or: The book is on the top of the table in the café.

But we also had ‘no’ connecting Dazai-san and book: Dazaisan no hon! ‘no’ is a connector particle and also shows ownership!

Dazaisan no hon: Dazai-san’s book Atsushisan no chazuke: Atsushi-san’s chazuke Chuuyasan no boushi: Chuuya-san’s hat Watashi no kimono: My kimono

So, putting everything together, we have: Dazaisan no hon wa kafe no teeburu no ue ni arimasu. Dazai-san’s book in on the table in the café.

But if I’m speaking TO Dazai-san and I say this exact sentence, it means more colloquially: “YOUR book is on the table in the café.” Since if you remember from Lesson 0, it is polite to refer to the person you are talking to with their name if you know it.

And finally, some other important location words come from the Ko-So-A Series that I introduced in Lesson 1! This is really a Ko-So-A-Do series because we have:

ここ• here そこ• there あそこ• over there どこ• where

And remember: Ko~ for locations closer to the speaker (yourself, if you are the speaker) So~ for locations closer to the listener A~ for locations far from both the speaker and listener

So I can easily say, “The book is here, Dazai-san!” Dazai-san, hon wa koko ni arimasu. (A wa B ni arimasu.)

With koko, soko, asoko, and doko, you can also replace ‘ni arimasu’ with desu: Hon wa koko desu.

Hon wa doko desu ka: Lit. Where is the book? Hon wa doko ni arimasu ka: Lit. Where is the book located?

So now you can say where all sorts of things and people are located in relation to other things and people!

As a final note, you can use iru and aru to say that somebody has a thing or person. For example:

Watashi wa kimono ga arimasu. I have a kimono. Chuuyasan wa boushi ga arimasu. Chuuya-san has a hat. Akutagawasan wa imoutosan ga imasu. Akutagawa-san has a younger sister.

It’s important to try not to mix up iru and aru!! Why? Well, if you say ‘aru’ in regards to a person, that brings to mind the image of their body existing in a location, rather than the fact that they are living and existing in a location:

*near the river*

Dazai-san wa asoko ni arimasu.

Atsushi *worried*: Dazai-san wa doko desu ka? Kyouka *points near the river*: Asoko ni arimasu. Atsushi: Dazai-saaaan! <sobbing> Kyouka: ……sorry, I mean imasu. Dazai-san wa asoki ni imasu. (-_-;)

Dazai-san wa asoki ni imasu. (-_-;)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omake 3: Jikoshoukai!

Jikoshoukai shimasu! Jikoshoukai means self introduction.

自己紹介 じこしょうかい

じこ ‘jiko’ means oneself and しょうかい ‘shoukai’ means introduction.

じこしょうかいしまあす。 ‘Jikoshoukai shimasu’ means “I will do my self-introduction.” or “I will introduce myself.”

You’ll actually hear this word a lot in anime now that you know what it is. It’s really important in Japanese culture! In fact, these are jikoshoukai, even if they don’t say ‘jikoshoukai’:

So polite~! And me~! ╰(▔∀▔)╯

Of course, you could just say your name and where you work, but you can also include where you’re from, what you like, your hobbies, all sorts of stuff!

You know what else is fun about Japanese culture? Word play. For instance, ‘jiko’ with different kanji (事故) also means ‘accident’, as in a car crash type of accident...

じこしょうかいします。 “Jikoshoukai shimasu.” aka, “Let me tell you about my accident….”

...Sorry, Ango-san, bad joke.... (⌒_⌒;)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omake 2

Weretiger is ‘jinko’: 人虎 人 虎 jin ko man tiger

Jinko not ‘jinkou’, which means population. 人口

JINKOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

Hard to tell when certain people are yelling…. (¬_¬;)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omake 1

Since I occasionally run across funny sentences or interesting grammar points that are too early to put into a lesson, I’ve decided to include short ‘omake’ or extras!

I came across this sentence: ぼーっとしていて、昨日財布をどこかに落としてしまったんです。

which some of my American friends translated as (using Google): “I was drowning, and dropped my wallet somewhere yesterday.”

I was drowning, and dropped my wallet somewhere yesterday. (-_-;)・・・

It actually means: “I was being absent minded, and unfortunately dropped my wallet somewhere yesterday.” Which somehow still sounds like Dazai-san (¬_¬;)

How google comes up with ‘drowning’, I have no idea! ヽ(ˇヘˇ)ノ

Anyway, rapid sentence breakdown:

ぼーっとする botto suru: to do nothing worthwhile; to abstractedly/dazedly/dreamily do something, aka to be absent minded ~ていた: ~teita: was doing X ~て: te form: sentence/verb connector ぼーっとしていて: botto shiteite: was being absent minded 昨日: きのう:kinou: yesterday 財布: さいふ:saifu: wallet を: o particle: marks a direct object (the thing you do an action on) どこか: dokoka: somewhere に: ni particle: marks direction/location 落とす: おとす:otosu: to drop 落として: おとして:te form of otosu ~てしまう: ~teshimau: ‘unfortunately does X/ X unfortunately happens’ ~てしまった: ~teshimatta: past tense: unfortunately did X ~んです:~ ndesu: ‘n’ added to plain forms, gives a bit of emotion or empathy, and followed by da or desu

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesson 1: A is B

Topics: A is B, Intro to Plain vs Polite, Nouns, Intro to wa Particle, Question Words Nani, Question Particle ka, Ko-So-A Series

Okay, time for Lesson 1!

This will be a simple lesson, even if it might be a little lengthy ^^ . Well, I suppose they’ll all seem a little lengthy in tumblr posts.

In this lesson, we’ll learn how to say what objects and people are, and ask what things are. The more vocabulary you know, the more you’ll be able to say! But we could go on forever about vocabulary nouns, so if there are specific kinds of words you want to know, feel free to ask! But for now *looks around* we’ll stick to what we can find in the Agency office! ヽ(o^▽^o)ノ

(Find the rest of the lesson under the cut!)

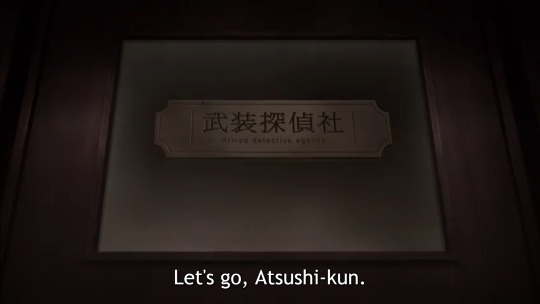

武装探偵社• ぶそうたんていしゃ• Busoutanteisha • Armed Detective Agency

In Japan, your choice of words (mainly verb conjugation) will depend on the level of politeness that you decide to use in your conversations. Just like in English, when talking to one’s Boss, we tend to use language that is a bit more polite than if we’re talking and joking around with friends, or even having a casual conversation among coworkers. The relative level of seniority also affects the choice of words and politeness level each partner in a conversation will use. Just like I mentioned in the previous lesson, I will use more polite language when talking to Dazai-san, and he will use more informal language when talking to me ^^

A is B. A wa B desu

In Japanese, the basic sentence ending, if no other verbs are being used, is:

だ da (Dictionary/Plain form)

of which the polite form, for normal, polite conversation is:

です desu (Polite)

wa•は

The wa particle is used to mark the topic that you are talking about. A literal translation into English could be specifically ‘as for’, or, more generally, ‘is’. But the reason it’s important to remember that ‘wa’ isn’t exactly just ‘is’ is because in later lessons, you’ll see that it can be used to highlight contrast between different things, and you can have several wa’s in a sentence. But don’t worry about that right now.

Here’s a simple example:

私は鏡花です。

わたしはきょうかです。

Watashi wa Kyouka desu.

Lit: As for me, I am Kyouka.

Or, more colloquially, simply: I am Kyouka.

彼は太宰さんです。

かれはだざいさんです。

Kare wa Dazai-san desu.

Lit: As for him, he is Dazai.

Or, simply: He is Dazai.

私•わたし• watashi = polite ‘I’, used by males and females

彼•かれ• kare = he/him

A Bit About Politeness

This is a good time to talk a bit about politeness level! I can say ‘I am Kyouka’ in several different ways:

Watashi wa Kyouka desu.

Watashi wa Kyouka da. this one sounds masculine with the ‘da’ ending ^^

Watashi wa Kyouka.

Watashi Kyouka.

The general trend is that the longer the sentence, the more polite it is! That is not always the case, but it is most of the time!

If it’s understood that I’m the topic, I don’t need to use ‘watashi wa’. Dropping the topic of the sentence does not make it less polite, but it does introduce ambiguity if you don’t know who people are referring to.

Kyouka desu.

Kyouka da.

Kyouka.

Japanese is interesting in that, I can pick up a book and say ‘Hon desu.’, and it’s a complete sentence! Literally, I’m only saying ‘Book’! But it would be translated as ‘This is a book.’

Ko-so-a

Speaking of the word ‘this’ or ‘that’…. There are 9 different words!

Yes! There are nine! And their use depends on several things!

1: the relative location of the object between you and your listener

2: whether the word ‘that’ is modifying a noun: that dog, this pencil

3: if you’re talking about a person or an object!

Don’t worry, this is not as hard as it sounds (* ^ ω ^)

Ko~ for things located closer to the speaker (yourself, if you are the speaker)

So~ for things located closer to the listener

A~ for things far from both the speaker and listener

これ• kore = this

それ• sore = that

あれ• are = that over there

This will make more sense with some examples!

For example, if I pick up a book, and I’m talking to Atsushi-san, and I want to say, “This is a book”, I could say:

これは本です。

これはほんです。

Kore wa hon desu.

This is a book.

Plain:

Kore wa hon da.

More plain:

Kore wa hon.

Even:

Kore, hon!

‘Hon desu.’ and ‘Hon da.’ can also be used, since it’s clear we’re referring to the book in my hand!

As for Atsushi-san, since the book is closer to me than to him, he would say, when referring to the same book:

Sore wa hon desu.

That is a book.

And Dazai-san would also say:

Sore wa hon desu!

That is a book!

Because the book is also closer to me than to him. But, if we’re talking about a book on the desk across the room, all of us would say:

Are wa hon desu!

That over there is a book!

Because the book is not really close to any of us!

We can do the same thing with any object!

鉛筆•えんぴつ• enpitsu • pencil

Kore wa enpitsu desu.

Sore wa enpitsu desu.

Are wa enpitsu desu.

予定表•よていひょう• yoteihyou • schedule

Kore wa yoteihyou desu.

Sore wa yoteihyou desu.

Are wa yoteihyou desu.

これは予定表です。Kore wa yoteihyou desu. This is a schedule. *This is not a schedule, this is an IDEAL!*

Question word Nani

Two other important words we need are ‘nani = what’, so we can make questions, and ‘ka’, which is like a spoken question mark!

何•なに• nani = what

か• ka = question particle

*Important point: Nani becomes ‘nan’ when it is in front of desu or da. Nani desu ka sounds weird~

*points at something closer to Dazai*

Dazai-san, sore wa nan desu ka?

Dazai: Kore? Kore wa konpyuuta desu.

(This? This is a computer.)

*points again to something closer to Atsushi*

Atsushi-san, sore wa?

Atsushi: Kore desu ka? Kore wa kami desu!

(You mean this? This is paper!)

*picks up an object*

Kore, nani?

Atsushi: Sore wa enpitsu desu.

As you can see, there are several different ways you can ask ‘What is that?/this?’ and they have varying levels of politeness.

What is that?

Sore wa nan desu ka?

Sore wa nani?

Sore wa?

Sore, nani?

You mean this?

Kore desu ka?

Kore desu?

Kore?

You can see that ‘kore’, ‘sore’, and also ‘are’ can be used alone to refer to an object that is being indicated by an action such as pointing or holding.

How about referring to people? It is very rude to say:

“Kore wa Dazai-san desu.” (⌒_⌒;)

when referring to a person, because ‘kore, sore, are’ are used only for things! So instead, we use:

こちら• kochira = this (person)

そちら• sochira = that (person)

あちら• achira = that (person) over there

“Kochira wa Dazai-san desu.”

Is much more polite! <( ̄︶ ̄)>

Sochira isn’t used often for people, because usually when you’re introducing someone, you’re standing next to the person you’re introducing, so ‘sochira’ is a little odd. You could use ‘achira’ when referring to someone across the room, though.

Go ahead, grab an imaginary friend (or a real friend), sit them down next to you, and practice asking, pointing out, and telling each other what various items in your room are (or use the photo of the Agency, pretending you’re various people in the room)! Remember, you ‘kore’ for items closer to you than your friend, your friend uses ‘kore’ for items closer to them; you use ‘sore’ for items closer to your friend, and your friend does the same for items closer to you; and you both use ‘are’ for items relatively farther from both of you. It’s pretty relative, so use your judgement – you don’t actually have to get out a ruler to measure whether an item is closer to you or your friend if it’s on the other side of the room, just use ‘are’!

Here is a list of words:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

机•つくえ•tsukue•Desk

鉛筆•えんぴつ•enpitsu•Pencil

ペン•pen•Pen

紙•かみ•kami•Paper

包帯•ほうたい•houtai•Bandages

ノート•nooto•Notebook (like the lined kind used for school)

手帳•てちょう•techou•Notebook (small pocket sized for keeping schedules, appointments, Kunikida-san’s notebook is actually this)

予定表•よていひょう•yoteihyou• schedule

椅子•いす•isu•Chair

窓•まど•mado•Window

ドア•doa•Door

床•ゆか•yuka•Floor

壁•かべ•kabe•Wall

天井•てんじょう•tenjou•Ceiling

帽子•ぼうし•boushi•Hat

携帯電話•けいたいでんわ•keitaidenwa•Cell phone

電話•でんわ•denwa•Telephone

コンピュータ•konpyuuta•Computer

本•ほん•hon•Book

小説•しょうせつ•shousetsu•Novel

文庫•ぶんこ•bunko•Small novel of the kind usually produced in Japan. All the BSD novels are bunko! ^^

虎•とら•tora•Tiger

人虎•じんこ•jinko•Weretiger

鉢植えの花•はちうえのはな•hachiue no hana•Potted plant

カップ•kappu•Cup

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Okay, so say you want to say “this book”. This is not the same thing as saying “This is a book”, because you know it’s a book, now you’re just specifying ‘this’ book. When using ‘this’ or ‘that’ like an adjective to modify a noun, we use:

kono = this (+ thing)

sono = that (+ thing)

ano = that (+ thing) over there

Kono hon

This book

Sono hon

That book

Ano hon

That book over there

Kono, sono, and ano cannot be used by themselves, they always have to be attached to a noun of some sort! ‘Kono wa hon’ makes no sense! Well….it would probably still be understood but….it would sound very weird!

That’s it for today~! I know it was kind of long, so I’ll try to keep it shorter for next time. I have a major test this week, so the next one will be out next weekend!

頑張って! がん��って! Ganbatte~! Do your best~! ☆*:.。.o(≧▽≦)o.。.:*☆

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I notice that the ask thing says Hai, very cleaver my dear! Could you explain why people say Kun, San, Sama, ect. After they say someone's name? It's confused me for quite awhile -Higumom

That’s a great question Higumom!! ( ^ ω ^) Actually, the perfect topic to start with, so maybe this is Lesson 0?

LESSON 0: Japanese Honorific Titles

So, what’s the difference between –san, -kun, -sama, and all that? They’re all different endings that you can attach on to names, and occasionally other nouns of position, like doctors or lawyers or even bakers! They can be attached to first or last names! Whether you use a first or last name actually depends on your personal relationship with the person you’re speaking to or about.

-san (さん) is the standard politeness level, and is like a conventional Mr/Mrs/Miss. You can use this with just about anybody you meet once you learn their name without offending them. Along with this, you would typically use someone’s last name + san if you just met them, and until they tell you to call them by their first name. I add –san to everyone’s name when I talk to them <( ̄︶ ̄)>

太宰さん • だざい • Dazai-san

敦さん • あつしさん • Atsushi-san

皆さん• みんなさん• Minna-san • Everyone (polite)

お客さん• おきゃくさん• O-Kyaku-san • Mr. Customer

You can even add –san to the word for a shop in order to refer to the owner!

パンやさん• Panya-san • Mr. Baker (literally, Mr. Bread shop!)

本屋さん• ほんやさん• Honya-san • Mr. Bookshop owner (Mr. Bookshop!)

肉やさん• にくやさん• Nikuya-san • Mr. Butcher (Mr. Butcher shop!)

医者さん• いしゃさん• Isha-san • Mr. Doctor

Companies even use –san to refer to other companies, which is common on small maps in phonebooks and business cards. The ADA could be referred to as:

武装探偵社さん• ぶそうたんていしゃさん• Busoutanteisha-san • Mr. Armed Detective Agency! ヽ(・∀・)ノ

We can even use –san as a cute way to refer to an animal or inanimate object ^^

うさぎさん• Usagi-san • Mr. Bunny /(^ × ^)\

魚さん• さかなさん• Sakana-san • Mr. Fish or Mr. Fishy!

-sama (さま) is much more respectful than –san and is often used by people in the business and service sectors to refer to their customers. It’s often written on letters instead of –san, and you’ll see it often on Japanese receipts from just about any store! Of course, you can also use it to refer to someone you really respect, if their position relative to you warrants it. We also tend to use it to refer to various gods.

お客様• おきゃくさま • O-Kyaku-sama • Honored customer

皆さま• みんなさま• Everyone (honorific)

神さま• かみさま• Kami-sama • Honored God (シ_ _)シ

-kun (君• くん) is more informal and is usually used by people of more senior ranking to refer to people of more junior ranking, or among male colleages, or between male friends. You can certainly address male children with –kun attached to their name, or to close friends and family of any gender. But it can even be used by males of more senior status to younger female employees! This is why Dazai-san occasionally calls me Kyouka-kun ^^

鏡花君 • きょうかくん• Kyouka-kun

樋口君• ひぐちくん• Higuchi-kun <3

-chan (ちゃん) is also informal and shows that the speaker finds a person endearing or cute, and adds a sense of cuteness to the name (chan is cuter than san!). Of course it would be rude to use this with strangers. You can use it for babies, young girls, female friends, grandparents, and even young boys! It’s very common for mothers to shorten their son’s name and attach –chan or –kun to it as a nickname! It’ll eventually get dropped as the boy gets older, at least in public ^^ Atsushi-san always calls me this (≧◡≦)

鏡花ちゃん• きょうかちゃん • Kyouka-chan

あくちゃん• Aku-chan or あっくん• Akkun (Akutagawa)

I’ll bet Gin-san used to refer to Akutagawa-san like that ^^

It’s also used to refer to cute things and animals!!

猫ちゃん• ねこちゃん• Neko-chan

-tan (たん) An even more cute version of –chan!! It’s like baby talk (widdle instead of little) and mascots often have it added onto their names. Only used with young children in a family or among very close friends or family to add cuteness as a nickname. Actually, all sorts of different endings can be made up to create a cute nickname (*≧ω≦*)

-shachou (社長• しゃちょう) Company president. In the working environment, it is very common to use your boss’s title when referring to them, or other appropriate titles to refer to other workers. You can also use the title as a standalone as well, without attaching it to a name:

福沢社長• ふくざわしゃちょう• Fukuzawa-shachou •Company President Fukuzawa

部長• ぶちょう• Buchou • Department Manager

課長• かちょう• Kachou • Section Chief

会長• かいちょう• Kaichou • President/Chairman

-sensei (先生せんせい) Used to refer to people who have authority in a particular field of knowledge, like a teacher, doctor, artists, musicians, accomplished writers, martial arts leader, etc. It can also be used as a standalone title without the person’s name! Kunikida-san would have been called this by the students in his math classes!

國木田先生• くにきだせんせい• Kunikida-sensei • Prof. Kunikida

-hakase (博士• はかせ) Does this one sound familiar to anyone? I’ve heard it used by Ash in referring to his Pokemon professor in the new Alola anime ^^ Similar to sensei, but this should be used if the teacher has a doctorate’s degree to indicate much higher learning! Like Sensei, it can be used as a standalone title. Literally means Professor, whereas Sensei can be translated as ‘professor’ or ‘teacher’.

-senpai (先輩• せんぱい) Senior. Used to refer to somebody of senior status (more experience) in a school, workplace, or club. It can be used as a title on its own or attached to a name.

kouhai (後輩• こうはい) Junior, the opposite of senior, but you don’t actually use this one as a form of address!! A junior would simply be addressed with their name + kun or some appropriate suffix!

tono (殿• との) Historical title used to refer to a feudal lord or samurai! But mainly used in official documents and certificates now. It becomes ‘-dono’ when attached to a name.

殿• との • Tono • Lord

信長殿• のぶながどの • Nobunaga-dono • Lord Nobunaga

-ue (上• うえ) This literally means above, and gives a high level of respect. It’s not really used anymore, but was commonly used to refer to one’s own mother, father, or sister when speaking to them. I don’t think Chuuya-san uses this term to refer to Kouyou-san…

父上•ちちうえ• chichi-ue • Honored Father

母上• ははうえ• haha-ue • Honored Mother

姉上•あねうえ• ane-ue • Honored Older Sister

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

You rarely use honorific titles to refer to your own self, unless you want to be seen as arrogant…

Oh, one final note, is that Japanese people rarely say the word ‘you’ when speaking to someone! Unless, of course you’re deliberately being rude, or you don’t know the person’s name and absolutely have to refer to them in some way. Normally, you use the person’s name plus appropriate suffix. So if I was talking to Chuuya-san and wanted to ask him what he ate for lunch, I could say, “Chuuya-san wa nani o tabemashita ka?”, which literally translates to “What did Chuuya-san eat?”, which in English sounds kinda cute when you’re speaking directly to that person. A more natural English translation would be, “What did you eat?”

Wow, Higuchi-san, this took a while! Great question!! I’ll probably get Lesson 1 out tomorrow ^^

30 notes

·

View notes