Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Perhaps the most-terrifying space photograph around.

Astronaut Bruce McCandless II floats untethered away from the safety of the space shuttle, with nothing but his Manned Maneuvering Unit keeping him alive. The first person in history to do so.

Credit: NASA

106K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Picture made by Sentinel 3 satellite on 10th August. The effects of drought and extreme high temperatures are clearly visible from space.

Source and details >>

by @spatialanalysis

456 notes

·

View notes

Photo

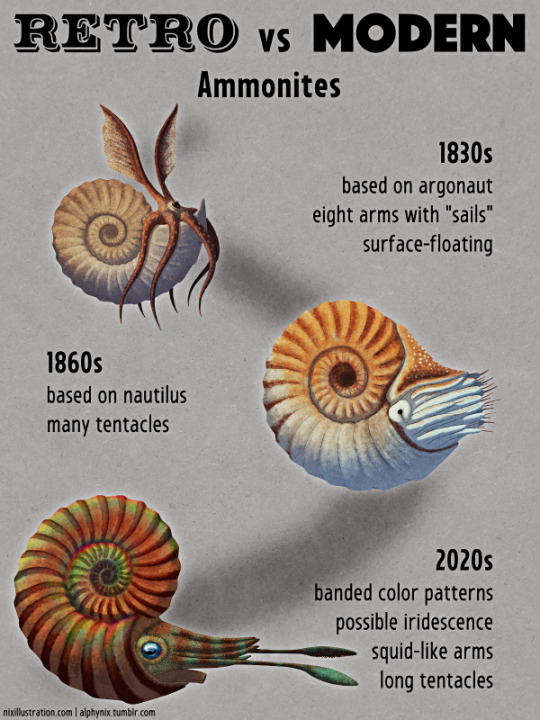

Retro vs Modern #17: Ammonites

Ammonites (or ammonoids) are highly distinctive and instantly recognizable fossils that have been found all around the world for thousands of years, and have been associated with a wide range of folkloric and mythologic interpretations – including snakestones, buffalo stones, shaligrams, and the horns of Ammon, with the latter eventually inspiring the scientific name for this group of ancient molluscs.

(Unlike the other entries in this series the reconstructions shown here are somewhat generalized ammonites. They’re not intended to depict a specific species, but the shell shape is mostly based on Asteroceras obtusum.)

1830s

It was only in the 1700s that ammonites began to be recognized as the remains of cephalopod shells, but the lack of soft part impressions made the rest of their anatomy a mystery. The very first known life reconstruction was part of the Duria Antiquior scene painted in 1830, but to modern eyes it probably isn’t immediately obvious as even being an ammonite, depicted as a strange little boat-like thing to the right of the battling ichthyosaur and plesiosaur.

The argonaut octopus, or “paper nautilus”, was considered to be the closest living model for ammonites at the time due to superficial similarities in its “shell” shape, but these modern animals were also rather poorly understood. They were commonly inaccurately illustrated as floating around on the ocean surface using the expanded surfaces on two of their tentacles as “sails” – and so ammonites were initially reconstructed in the same way.

1860s

While increasing scientific knowledge of the chambered nautilus led to it being proposed as a better model for ammonites in the mid-1830s, the argonaut-style depictions continued for several decades.

Interestingly the earliest known non-argonaut reconstruction of an ammonite, in the first edition of La Terre Avant Le Déluge in 1863, actually showed a very squid-like animal inside an ammonite shell, with eight arms and two longer tentacles. But this was quickly “corrected” in later editions to a much more nautilus-like version with numerous cirri-like tentacles and a large hood.

The nautilus model for ammonites eventually became the standard by the end of the 19th century, although they continued to be reconstructed as surface-floaters. Bottom-dwelling ammonite interpretations were also popular for a while in the early 20th century, being shown as creeping animals with nautilus-like anatomy and numerous octopus-like tentacles, before open water active swimmers eventually became the standard representation.

2020s

During the 20th century opinions on the closest living relatives of ammonites began to shift away from nautiluses and towards the coleoids (squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses). The consensus by the 1990s was that both ammonites and coleoids had a common ancestry within the bactridids, and ammonites were considered to have likely had ten arms (at least ancestrally) and were probably much more squid-like after all.

Little was still actually known about these cephalopods’ soft parts, but some internal anatomy had at least been figured out by the early 21st century. Enigmatic fossils known as aptychi had been found preserved in position within ammonite shell cavities, and were initially thought to be an operculum closing off the shell against predators – but are currently considered to instead be part of the jaw apparatus along with a radula.

Tentative ink sac traces were also found in some specimens (although these are now disputed), and what were thought to be poorly-preserved digestive organs, but the actual external life appearance of ammonites was still basically unknown. By the mid-2010s the best guess reconstructions were based on muscle attachment sites that suggested the presence of a large squid-like siphon.

Possible evidence of banded color patterns were also sometimes found preserved on shells, while others showed iridescent patterns that might have been visible on the surface in life.

In the late 2010s the continued scarcity of ammonite soft tissue was potentially explained as being the same reason true squid fossils are so incredibly rare – their biochemistry may have simply been incompatible with the vast majority of preservation conditions.

But then something amazing happened.

In early 2021 a “naked” ammonite missing its shell was described, preserving most of the body in exceptional detail – although frustratingly the arms were missing, giving no clarification to their possible number or arrangement. But then just a few months later another study focusing on mysterious hook-like structures in some ammonite fossils concluded that they came from the clubbed tips of a pair of long squid-like tentacles – the first direct evidence of any ammonite appendages!

A third soft-tissue study at the end of the year added in some further confirmation that ammonites were much more coleoid-like than nautilus-like, with more evidence of a squid-style siphon, along with evidece of powerful muscles that retracted the ammonite’s body deep inside its shell cavity for protection.

Since ammonites existed for over 340 million years in a wide range of habitats and ecological roles, and came in a massive variety of shapes and sizes, it’s extremely likely that their soft anatomy was just as diverse as their shells – so there’s no single “one reconstruction fits all” for their life appearances. Still, at least we now have something less speculative to work with for restorations, even if it’s a bit generalized and composite, and now that we’re finally starting to find that elusive soft tissue there’s the potential for us to discover so much more about these iconic fossil animals.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

3K notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Thinking about Sponge

In the split second between “I’m hungry” and “Ooh, a nice salad” millions of fizzling brain cells, or neurons, meet at junctions called synapses to communicate our desires (cake), our awareness (already had cake) and our memories (what’s in the fridge?). Of course, our synapses are involved in many different types of activity, but feeding might be where it all began. In this freshwater sponge (Spongilla lacustris) – pictured using electron microscopy – scientists find synapse-like structures, even though this primitive animal doesn’t have a nervous system. Zooming inside one of its feeding chambers, we see neuron-like ‘neuroid’ cells (highlighted in purple) reaching out, using chemicals to communicate with digestive cells called choanocytes (blue, green and yellow). While researchers spot similarities with human neurons squirting neurotransmitters into synapses – and making use of similar genes – it’s perhaps not surprising that the first thoughts evolved from where the next meal is coming from.

Written by John Ankers

Video by Jacob Musser, Giulia Mizzon, Constantin Pape & Nicole Schieber / EMBL

Developmental Biology Unit, European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), Heidelberg, Germany

Video originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Research published in Science, November 2021

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

20 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

This ghostly giant is a rare sight. 😮

But last month, MBARI researchers spotted this giant phantom jelly (Stygiomedusa gigantea) with the ROV Doc Ricketts 990 meters (3,200 feet) deep in Monterey Bay. The bell of this deep-sea denizen is more than one meter (3.3 feet) across and trails four ribbon-like oral (or mouth) arms that can grow more than 10 meters (33 feet) in length. MBARI’s ROVs have logged thousands of dives, yet we have only seen this spectacular species nine times.

The giant phantom jelly was first collected in 1899. Since then, scientists have only encountered this animal about 100 times. It appears to have a worldwide distribution and has been recorded in all ocean basins except for the Arctic. The challenges of accessing its deep-water habitat contribute to the relative scarcity of sightings for such a large and broadly distributed species.

Historically, scientists relied on trawl nets to study deep-sea animals. These nets can be effective for studying hardy animals such as fishes, crustaceans, and squids, but jellies turn to gelatinous goo in trawl nets. The cameras on MBARI’s ROVs have allowed MBARI researchers to study these animals intact in their natural environment. High-definition—and now 4K—video of the giant phantom jelly captures stunning details about the animal’s appearance and behaviors that scientists would not have been able to see with a trawl-caught specimen.

Check out this and other iconic deep-sea animals on our Creature feature.

youtube

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

First part of a commission for @leporidaefluff , a bear in autumn forest on an amazing orange labradorite

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

crying bc of velvet worms. they literally have little legs

10K notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on Acetabularia?

a single-celled organism that looks pretty and knows when to quit, I give it 9/10

1K notes

·

View notes