Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The #1 Career Mistake Capable People Make | LinkedIn

I recently reviewed a resume for a colleague who was trying to define a clearer career strategy. She has terrific experience. And yet, as I looked through it I could see the problem she was concerned about: she had done so many good things in so many different fields it was hard to know what was distinctive about her.

As we talked it became clear the resume was only the symptom of a deeper issue. In an attempt to be useful and adaptable she has said yes to too many good projects and opportunities. She has ended up feeling overworked and underutilized. It is easy to see how people end up in her situation:

Step 1: Capable people are driven to achieve.

Step 2: Other people see they are capable and give them assignments.

Step 3: Capable people gain a reputation as "go to" people. They become "good old [insert name] who is always there when you need him." There is lots right with this, unless or until...

Step 4: Capable people end up doing lots of projects well but are distracted from what would otherwise be their highest point of contribution which I define as the intersection of talent, passion and market (see more on this in the Harvard Business Review article The Disciplined Pursuit of Less). Then, both the company and the employee lose out.

When this happens, some of the responsibility lies with out-of-touch managers who are too busy or distracted to notice the very best use of their people. But some of the responsibility lies with us. Perhaps we need to be more deliberate and discerning in navigating our own careers.

In the conversation above, we spent some time to identify my colleague's Highest Point of Contribution and develop a plan of action for a more focused career strategy.

We followed a simple process similar to one I write about here: If You Don’t Design Your Career, Someone Else Will. My friend is not alone. Indeed, in coaching and teaching managers and executives around the world it strikes me that failure to be conscientious about this represents the #1 mistake, in frequency, I see capable people make in their careers.

Using a camping metaphor, capable people often add additional poles of the same height to their career tent. We end up with 10, 20 or 30 poles of the same height, somehow hoping the tent will go higher. I don't just mean higher on the career ladder either. I mean higher in terms of our ability to contribute.

The slightly painful truth is, at any one time there is only one piece of real estate we can "own" in another person’s mind. People can't think of us as a project manager, professor, attorney, insurance agent, editor and entrepreneur all at exactly the same time. They may all be true about us but people can only think of us as one thing first. At any one time there is only one phrase that can follow our name. Might we be better served by asking, at least occasionally, whether the various projects we have add up to a longer pole?

I saw this illustrated some time ago in one of the more distinctive resumes I have seen. It belonged to a Stanford Law School Professor [there it is: the single phrase that follows his name, the longest pole in his career tent]. His resume was clean and concise. For each entry there was one impressive title/role/school and a succinct description of what he had achieved. Each sentence seemed to say more than ten typical bullet points in many resumes I have seen. When he was at university he had been the student body president, under "teaching" he was teacher of the year and so on.

Being able to do many things is important in many jobs today. Broad understanding also is a must. But developing greater discernment about what is distinctive about us can be a great advantage. Instead of simply doing more things we need to find, at every phase in our careers, our highest point of contribution.

I look forward to your thoughts below and @gregorymckeown.

via linkedin.com

0 notes

Photo

Tiny Off-Grid Cabin in Maine is Completely Self-Sustaining | Inhabitat - Sustainable Design Innovation, Eco Architecture, Green Building

via inhabitat.com

0 notes

Text

Cities of the future should be designed with wellbeing in mind | Guardian Sustainable Business | Guardian Professional

At one time (up to the early 1900s), it was taken for granted that housing was inextricably tied up with health. According to one writer in the Lancet medical journal in 1923: "There is no need to emphasise in these columns the vital connexion between housing and health. The latter, whether physical or moral, is perhaps more dependent upon good housing than upon any other single factor in national affairs".

But the advent of dedicated health service providers (through the NHS) and the parallel growth of drug companies fuelled an increasingly medical response to health provision and, more specifically, a focus on treatment of ill health. At the same time, new built environment disciplines were developing and, while town planners focused on economic development and environmental protection, architecture aligned itself with the discipline of art.

The 21st century has brought new health challenges, such as longevity and a massive growth in lifestyle-related diseases, and with these new challenges has also come a renewed interest in housing and the wider built environment.

We know that where you live matters – you are likely to live longer in certain places (regardless of your economic circumstances) – and we know that some places just make us feel good while others are depressing. We're not so good at knowing what makes the difference. Think about your favourite place. What is it about this place, whether it's an Italian square or a loft apartment, that makes it attractive? If we could find out then maybe we could recreate this in new or redesigned places? In 2004, I set up the Wise (the wellbeing in sustainable environments) research unit, now based at the University of Warwick, to do just that.

Initially, most researchers were interested in obesity and how neighbourhoods could be designed to promote walking. However, at a time when we are all living longer and can expect to enjoy many disease-free years, perhaps the key challenge of the 21st century is to improve our wellbeing – to ensure we are happy as well as healthy. After all, what is the point of living a long life if we do not enjoy it?

The recession has reminded us that the pursuit of wealth is not necessarily the solution. It shocks me to see how cities of the future are often portrayed (for example in films): grim, dark and usually inward-looking environments. Surely we can do better than that?

Back in the early 20th century, Ebenezer Howard's solution for a healthy built environment was the garden city; the creation of relatively autonomous, leafy districts providing light-filled semi-detached houses and local shops and services. These districts still survive well today – for example, Bournville in Birmingham and Welwyn in Hertfordshire, but they are expensive places to live.

But we are starting to develop new models which might offer hope for the future. 'Urban villages' such as Poundbury, near Dorchester, are much criticised by the architectural community for their eclectic style, but there is little doubt that the pedestrian-oriented, high quality environment and inclusion of shops, restaurants and other local facilities, help to create a strong sense of community. Further afield, we can look to developments such as Bo01 in Malmö, Sweden, for a more innovative take on a rich urban environment. There are now numerous examples but to date we have little evidence on what design features make a difference.

Perhaps the key features of design for wellbeing are homes with enough space for family members to eat and relax together, with layouts that allow people to do their own thing without annoying everyone else; where effective sound insulation allows everyone to get a good night's sleep and where children reach their academic potential because they have space to concentrate on homework.

Other features include homes with plenty of natural light to boost our mood, and views of greenery to restore our energy; housing layouts in which people don't feel overlooked but are close enough to neighbours to bump into them in the street or chat over the garden fence; streets where children are safe to roam free, developing their motor skills and social networks; neighbourhoods where there are places to go, so that you are encouraged to walk around more; places that have their own unique identity, so you feel you belong and where you can stop and chat and meet friends or sit and watch the world go by.

There are problems that need to be overcome. At the moment no-one wants to impede housing development of any kind. Architects are used to thinking in terms of aesthetics and local authorities tend to leave housing development to others. However, the good news is that designing for wellbeing may not necessarily be more expensive. There has been debate recently about whether we should reintroduce space standards for housing. My view is that we don't need more space, just better space. And if, as consumers, we knew more about this 'better space', we could be more demanding.

It is shocking how little we know about the homes we decide to buy or rent. A house might be superficially appealing, but how is it going to affect our health and wellbeing over the long term? We would benefit from some sort of rating system which recognises design for wellbeing in housing. Just as for food we know not just what we like to eat but also what is likely to be good for us, in housing we could know a bit more about how a home is likely to affect different aspects of our wellbeing.

Imagine a world where homes, streets and neighbourhoods make you feel good about yourself, help you reach your potential, keep you healthy and safe, and support you in making good relationships. This is my vision for housing of the future – the pursuit of wellbeing and creation of spaces that help us to flourish.

Elizabeth Burton is a professor of sustainable building design and wellbeing at the University of Warwick. She is also research director of Wise

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox

via guardian.co.uk

0 notes

Text

Skylar Tibbits: Can we make things that make themselves? - YouTube

via youtube.com

0 notes

Text

Fixing the Fort - The Architect's Newspaper

Fort Mason Center, a military base turned cultural center on the San Francisco Bay, has announced that West 8, a Rotterdam-based planning and landscape architecture firm, will design a new master plan for the 13-acre waterfront site.

West 8’s scheme focuses on seven key strategies: the Fort’s legacy, ecological character, anchoring the Center, naval heritage, activation of the water’s edge, and branding. Their proposal includes a sinuous, partially-below-grade “gateway” building—the only completely new structure in the proposed master plan—housing the Center’s administrative offices.

Renderings showing the proposed transformation of the Pier 1 warehouse into an art-themed hotel. [Click images to enlarge.]

In what may be one of the more contentious changes, the plan envisions the transformation of the Pier 1 military warehouse into an “art-oriented” hotel. Past proposals for privately-operated hotels in the Presidio and Fort Baker met with considerable public opposition before eventually being opened.

The firm’s selection was the culmination of a design selection process that began with 20 invited firms. The list was then narrowed to three firms who prepared conceptual plans for the Center. The other two finalists were teams led by Bruner/Cott and AMP Arquitectos.

The sinuous new entry pavilion (top, left); barges with pedestrian space and swimming pools will be moored alongside the piers (center, right). [Click images to enlarge.]

The Fort Mason Center was created in 1977 from the former military complex of the same name. It is administered by the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, part of the National Park System. Overseen by a nonprofit board, the Center houses numerous nonprofit cultural and arts organizations and contains several large venue spaces. While the Center occupies some of the most desirable waterfront property on the San Francisco Bay, its facilities lack a cohesive urban concept and public access continued to be problematic.

Renderings show proposed changes along Fort Mason's piers. [Click images to enlarge.]

The West 8 team is comprised of nine firms and, incidentally, was the only team of the three finalists that included Bay Area designers and consultants. The design process will proceed as funding is identified; no firm timetable exists.

In addition to West 8, the team consists of: Jensen Architects, Bionic Landscape Architects, Architectural Resource Group, Ila Berman (all San Francisco based). Other consultants included Moffat & Nichol, HR&A Advisors, Langdon Associates, and Impark.

via archpaper.com

0 notes

Text

Exploratorium at Pier 15: A Green Machine - YouTube

via youtube.com

0 notes

Text

Dutch architects to use 3D printer to print a house

News: Dutch architecture studio Universe Architecture is planning to construct a house with a 3D printer for the first time.

The Landscape House will be printed in sections using the giant D-Shape printer, which can produce sections of up to 6 x 9 metres using a mixture of sand and a binding agent.

Architect Janjaap Ruijssenaars of Universe Architecture will collaborate with Italian inventor Enrico Dini, who developed the D-Shape printer, to build the house, which has a looping form based on a Möbius strip.

3D printing website 3ders.org quoted Ruijssenaars as saying: "It will be the first 3D printed building in the world. I hope it can be opened to the public when it's finished.”

The team are working with mathematician and artist Rinus Roelofs to develop the house, which they estimate will take around 18 months to complete.

The D-Shape printer will create hollow volumes that will be filled with fibre-reinforced concrete to give it strength. The volumes will then be joined together to create the house.

In 2009 architect Andrea Morgante used the D-Shape printer to create a 3m high pavilion, which was the largest object ever created on a 3D printer at the time.

In October last year, architects Softkill Design unveiled a proposal to print a house based on bone structures.

See all our stories about 3D printing.

via dezeen.com

0 notes

Photo

Fashion Photos With Whale Sharks | Smithsonian Blog

via blogs.smithsonianmag.com

0 notes

Text

11 Ways to Be More Mindful in Your Work Relationships « The Intentional Workplace

Do you know about the marshmallow test?

No, it’s not about seeing how many marshmallows you can toast and eat by the fire. It’s the classic Marshmallow Study conducted in 1968 at Stanford University by clinical psychologist Walter Mischel that became one of the longest running experiments in psychology. The initial study examined 600 children to see how they would behave when given a marshmallow and left alone. Each child was given a choice: wait for the experimenter and you get two marshmallows or just eat the marshmallow while you wait.

It’s fascinating to watch some of the children’s strategies for handling the choice. Subsequent follow-ups demonstrated that the children who waited – in other words, delayed gratification – performed better later in life with academics, attention, stress management and relationships than kids who rang the bell first (ate the marshmallow).

You may be wondering – what’s a 1968 study about children and marshmallows have to do with workplace relationships? While “mindfulness” was not on any scientist’s radar screen back then, the marshmallow study speaks to early patterns of self-control that follow us into our adulthood. Impulse control is learned early, and what’s still not completely understood is how much is native to a brain or learned through the power of social conditioning.

One thing is certain – while some of us may be born with more of a predisposition towards patience and self-discipline, none of us are born with the skills to be mindfully self-aware.

Take a few (delightful) minutes to watch this video of the children participating in the marshmallow study. Which one would you guess is most like you were as a kid? As much as I would like to think I had the willpower of the kid in the zebra suit, I’m probably more like the girl who ate bits of the marshmallow till it was gone and then took matters into her own hands and went looking for the person in charge.

Work Relationships are Rarely Easy

As I’ve written before in these pages, mindfulness is a skill that requires a commitment, over time, to develop and maintain desired behaviors. A daily meditation practice is only one way to engage acting mindfully.While there’s ample evidence of the physiological benefits of regular meditation, the practice alone won’t necessarily transform how you relate to other people.

Mindfully relating to others at work is an especially challenging and important skill. After all, relationships are the foundation of business. Business happens because people make it happen. Unless you work completely alone, you get things done with and through other people. And “performance” is based on feelings, even when those feelings are outside of conscious awareness.

One of the most significant findings of the last two decades is a greater understanding of the social nature of brains. Advances in our understanding of social neurobiology, show that our interactions with others shape our brain’s neural pathways including those that are genetically programmed. Recent studies show that the brain responds to nonverbal messages and emotional cue throughout life.

In his book, The Developing Mind, social neurobiologist Daniel Siegel uses the phrase the “feeling of being felt” to describe relationships that shape the mental circuits responsible for memory, emotion, and self-awareness. Brain altering communication is triggered by deeply felt emotions that register in facial expressions, eye contact, touch posture, movements, pace and timing, intensity and tone of voice.”

What You Value

If we place value on a growing body of neuroscience that demonstrates the impact and power of neural interdependency, the question becomes one of choice in deciding how to relate to others. Developing greater mindful awareness of our communication habits is one level of proficiency in relationship building. But it takes a deeper understanding of our motives in relating to others, especially in work relationships, to build mindfulness that can become our default state.

Developing greater mindfulness is a practice, the definition of which is simply, “done with repetition.” While you may want to be more mindful with your manager, expanding mindful awareness of your habits, in all of your work relationships, will give you better insights than simply focusing on one person, although that may be a good start. While there is often a tendency to want to “solve” our more intractable people problems first, try to resist the temptation to start with the most “difficult” person you know.

For beginners, it’s helpful to practice mindfulness when you are more relaxed to give yourself the space to calmly observe your reactions and those of others. Recognize that mindful awareness is not an “event” or “technique” or “strategy” that you use. Rather it is a commitment to a way of being that is transforming not only how you behave but how you perceive the world.

11 Ways to Practice

Clarify Your Intentions. As mentioned earlier, understand your motives. You may intend to be more patient or kinder with a specific colleague or with all the people you work with. Be clear with yourself about your intentions. What do you really want your outcomes to be –for you – and for others?

Think More Consciously. Being consciously self-aware means you are intimately aware of what, how and why you are thinking what you are thinking. Author Eckhart Tolle says that “When we can’t make up our minds, it’s because of our minds, or what I call “the voice inside your head.” Many people don’t even know they have this voice, but it’s talking away, creating a never-ending monologue.”

Develop Your Emotional Literacy. The more you engage in conscious thinking the more aware you will become of how those thoughts make you feel. Making the connection is the essence of emotional literacy. Expanding this knowledge enables you to manage your “negative” emotional triggers more skillfully and to cultivate the type of feelings that support you communicating more effectively with others.

Observe Your Behavior. We all have behavioral patterns with others, especially those people who we work with often. Some of these behaviors work – meaning they produce a positive result. Get to know what these are. Conversely, begin to note (by getting better at more closely observing others) what signals you send that provoke weak or negative responses in others. Over time, you’ll get a clearer picture of communication habits you have (that could be specific to an individual or more general) that you may choose to change.

Avoid Self-Absorption – In an era of chronic time pressures, poor attention and constant distraction, it’s easy to get overwhelmed and self-absorbed. If it’s always about you and your agenda, then it’s rarely about others. Non-verbal cues are always communicating what’s really on you mind. Paying attention to others is golden in our time-starved lifestyles. There’s no guarantee that you’ll get the full attention of the other person (they’re subject to the same cultural influences as you are in most cases) but at some level, your genuine interest will be felt.

Use Language Carefully. Language is power. Often the emphasis on nonverbal influence seems to diminish the value of words. Name calling in office environments has really gotten toxic. I cringe when I see courses or books from well-meaning consultants who refer to “problem” employees as “losers,” “slackers” “whiners, etc. When you label others, you de-personalize them. And when other people hear you use labels or make derogatory remarks about others, they will, at some level, assume you will so the same to them. http://blogs.hbr.org/bregman/2012/09/what-to-do-when-you-have-to-work-with-so...

Care About Others More. Yes, care more. How? Learn to engage your empathy, compassion and curiosity every day. Practice it. You are rewiring your brain when you forge these new habits. Research shows that when we are stressed, our focus becomes more internalized, resulting from anxiety that has switched on the stress response. As a result, we unconsciously switch off the part of our brains that generate empathy and compassion towards others. We’re in our own heads, trying to solve problems, make decisions and assuage our fears. Focusing on others is the last thing we’re thinking about. Often we feel and act as if changing our state is out of our control – it is not.

Learn to Express Disagreements & Even Anger Differently - Becoming more mindful in your relationships does not mean you have to become a saint or a pushover. The challenge is learning to be direct and assertive, where appropriate, without resorting to attacks, sarcasm or disrespect. There will be people that we work with whose behavior we do not like or condone. Being mindful in the face of such behavior can seem impossible, even unreasonable, but in response we must revisit #1 and ask ourselves – what are my intentions and what do I want my outcomes to be. If we decide that all we want is revenge, we must take the consequences. Mindful thinking about this process can be very valuable.

Letting Go of the Illusion of Control – Repeat this several times a day – I do not have the power to control or change others. Knowledge from neuroscience helps us to understand that the brain is always assessing potential threats or rewards from outside events. Most people perceive your motives at deep levels and act on them, often without any conscious awareness. Which signal do you want to activate when communicating with others?

Stop Judging Others. Your mental comparisons and evaluations are triggering your feelings – and those feelings leak through your body language. If you think I have an agenda (whatever that means) you are probably communicating that to me nonverbally. If you believe I am not as smart as you, I’m getting that at some level by how you are communicating with me.

Pay Attention to Cultural Influences. All work relationships happen within the context of the organization or situation in which you work. In other words – it’s the system! The mental models that shape the dynamics of an organization shape the patterns of communication within that system. According to Quantum Shifting author John Wenger, “Behaviors at work are tempered by the systemic norms.”�� The more you are aware of these factors, the better able you are to access how they influence you and your communication with others.

While you may not have much choice in who you work with, you can choose how you want to behave with them. When you behave towards other more mindfully, you’re likely to increase that others will perceive your positive intentions, even if your communication or actions aren’t perfect.

But remember intentions without actions won’t amount to the changes you would like to experience. “First, said the Greek sage and philosopher, Epictetus, say to yourself what would you be; and then do what you have to do.”

Thanks for reading and taking the time to comment, subscribe, share, like and tweet this article. It’s appreciated.

Louise Altman, Partner, Intentional Communication Consultants

0 notes

Text

Living Small - The Architect's Newspaper

Mayor Bloomberg named a local design team—nARCHITECTS, Monadnock Development, and Actors Fund Housing Development Corporation—as the winner of New York City’s adAPT NYC Competition. In July, Mayor Bloomberg and Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Mathew M. Wambua asked architects to think big but on a small scale by developing a micro-unit apartment housing model on a city-owned site—and that’s exactly what nARCHITECTS did when they conceived of “My Micro NY,” a 55-unit building that will offer affordable and bite-size housing, made up of units ranging between 250 and 375-square-feet.

Living units include multi-purpose spaces, high ceilings, and Juliette balconies.

After reviewing thirty-tree submissions from firms across the country, Bloomberg said they chose the design that made “innovative use of compact space” and was also “attractive, livable, and offered competitive priced rents.” The Museum of the City of New York will present the submissions from four notable teams at a new exhibit, Making Room: New Models for Housing New Yorkers, that includes: Jonathan Rose Companies, Curtis + Ginsburg, and Grimshaw; Durst Organization and Dattner Architects; Blesso Properties, Bronx Pro, Hollwich Kushner, James McCullar Architecture, and Handel Architects; Abby Hamlin, Chrystie Street Development, Rogers Marvel Architects, Future Expansion Architects, and Community Solutions.

The building will be one of the first multi-family building developed using modular construction in Manhattan. And like Atlantic Yards’ B2 development, it will be pre-fabricated at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Floor plans (left) and a diagram (right) of the units. Click to enlarge.

Eric Bunge, principal of nARCHITECTS, described the design layout as a “canvas and a toolbox,” which will provide plenty of light with 9’-10’’ floor-to-ceiling heights and Juliette balconies. Within the building, residents will have access to common spaces, a rooftop garden, a shared lounge, and a fitness room.

The city enlisted the help of leaders in the architecture field to provide feedback on the submissions, which included Maya Lin of Maya Lin Studio; Richard Plunz, Director the Urban Design Program at Columbia University; Barry Bergdoll, Chief Curator of Arhcitecture & Design at Museum of Modern Art, and Bjarke Ingels, architect and founding partner of BIG-Bjark Ingels Group.

via archpaper.com

0 notes

Text

Monastic Marvels: 12 Cliffside & Mountaintop Monasteries (Page 1) | WebUrbanist

Monastic Marvels: 12 Cliffside & Mountaintop Monasteries

Article by Steph, filed under Travel & Places in the Global category.

Clinging precariously to sheer cliff faces or perched on towering mountaintops and volcanic plugs, these 12 rocky monasteries throughout the world certainly provide inspiring views of the natural landscapes and cities around them. Built as early as the 3rd century BCE, these monasteries have been carved into stone, and are often deliberately difficult to access with dangerous ladders and rickety suspended paths.

Sumela Monastery, Turkey

(images via: wikimedia commons)

Located on a steep cliff at an altitude of about 3,900 feet in the Trabzon province of modern Turkey, the Sümela Monastery was founded in 386 AD in honor of the Virgin Mary. The monastery’s dramatic appearance and historical significance make it a major tourist attraction for the region. Built into the rock, the monastery has a rock church, several chapels, kitchens, student rooms, a guesthouse, a library and a sacred spring revered by Eastern Orthodox Christians.

Popa Taungkalat, Myanmar

(images via: wikimedia commons, preetamrai, scotted400)

Golden spires sparkle in the sunlight atop a rock platform that rises far above the rest of the landscape. Could the Popa Tuangkalat monastery be any more awe-inspiring? Elevated 2,417 feet above the plains of central Burma on an ancient volcanic plug, this monastery is accessed by 777 stairs. Tourists ascend eagerly to see the lush springs and streams, plentiful Macaque monkeys, and, of course, the view.

Meteora, Greece

(images via: cod_gabriel, thomas depenbusch, wentuq, ivan marcialis)

The Meteora complex in Greece features not just one, but six spectacular mountaintop monasteries built on elevated sandstone rock pillars. They include the Holy Monastery of Great Meteoron, which serves as a museum for tourists, as well as the Holy Monasteries of Varlaam, Rousanou, St. Nicholas Anapausas, St. Stephen and the Holy Trinity. Each was constructed in the 15th and 16th centuries, though the rock itself was inhabited by monks long before that. Access used to be deliberately strenuous, requiring a climb up long ladders lashed together. Goods – and people who couldn’t climb – were hauled up in large nets. The complex was bombed during World War II, and many of its art treasures were stolen. Today, it’s home to fewer than 10 inhabitants in each individual monastery, and serves mostly as a tourist attraction.

Mt. Huashan, China

(images via: overbreathing, wikimedia commons)

For many years, travelers and pilgrims have negotiated some of the world’s most dangerous roads and paths to reach the monastery that clings to the rock face of Mount Huashan in China. This was intentional, as access was only granted to those who had the will to face their fears, and the very real danger of falling along the way. However, as tourism has increased, safety measures have been put into place, and there are now cable cars and stone-built paths.

Hozoviotissa Monastery, Greece

(images via: manu 1, 2, 3)

Stark white against the mountain, in the tradition of Greek architecture, Hozoviotissa Monastery looks out over the sea from the island of Amorgos, the most eastern of the Cyclades. One of Greece’s most beautiful Byzantine monasteries, Hozoviotissa was founded in the 11th century and is now an attraction for tourists who come to the island to hike. It contains an icon of the Virgin Mary that, according to legend, ‘miraculously’ washed up on the shore of the island.

Cave Monasteries, Cappadocia, Turkey

(images via: wikimedia commons, alaskan dude, lwy, alaturkaturkey, vulcanus travel)

The stunning landscape of Cappadocia in Turkey looks like something from an alien planet, with hundreds of stone ‘fairy chimney’s rising from the earth. Set among the cliffs of this rocky city are a number of churches and monasteries. The Natural Rock Citadel of Uchisar is one of the highest peaks in the area, and inside it has been carved away with ancient tunnels and dwellings.

Next Page: Monastic Marvels 12 Cliffside Mountaintop Monasteries

1

2

Next Page »

Comment on Facebook

via weburbanist.com

0 notes

Text

A Marriage Between Buddhism and Science | The Amherst Student

B. Alan Wallace ’87 is not the typical Amherst alumnus. Author of more than 20 books on Buddhism and science and a practicing Buddhist monk for the entirety of his time at the College, he now goes on meditative retreats for months on end, performing psychological experiments in a lucid dream state to attempt to discover the true nature of reality, happiness and suffering.

Finding His Own Path

Wallace was born to a devoutly Christian family and spent his youth travelling the world with his Protestant theologian father. However, he was strongly interested in science from a young age and struggled to reconcile his passion for science with his deeply spiritual upbringing.

“I was looking for an integration of truth and meaning. Christianity offered meaning, but I couldn’t tell whether it was true; science offered truth, but I couldn’t see any meaning in it. I was looking for a true and meaningful life, and I didn’t see any real options or promising avenues,” Wallace said.

When he went to the Univ. of California-San Diego in 1968 to study ecology, he soon became disillusioned with both his classes and America in the turmoil of the Vietnam War. Seeking a change of scenery, he spent his junior year abroad, studying at the Univ. of Göttingen in Germany, where he first discovered Tibetan Buddhism. He quickly became engrossed by Tibetan culture and religion, discontinuing his university education and spending months in a local Buddhist monastery studying under the guidance of German monks. At last, he had found a belief system that united his love of science with his search for meaning.

“I found what I was looking for in Tibetan Buddhism. It’s very deeply experiential; it’s very sharp, very rational and intelligent — and it’s also profoundly meaningful. To my mind, it’s a true, comprehensive science of the mind that I haven’t found anywhere else. It’s both scientific and also deeply spiritual,” Wallace said.

During his time at the German monastery, a flier arrived announcing a year-long class on Tibetan Buddhism for Westerners taught in Dharamsala, India under the supervision of the Dalai Lama in exile. After meditating on the opportunity and seeking guidance from his lama at the monastery, Wallace decided to enroll in the course and traveled to India to begin perhaps the most transformative period of his life. Staying in the home of the Dalai Lama’s personal physician, Wallace fell in love with the freedom and intellectual fulfillment offered by his studies. After three months in the program, at the age of 21, Wallace had his first personal meeting with the Dalai Lama, and instantly knew he had found his mentor.

“I knew I found my spiritual guide or guru or lama if you’d like. He’s been my teacher ever since,” Wallace said.

After a year and a half in India, Wallace decided to take ordination as a novice monk and received full ordination as a Buddhist monk in 1975, administered personally by the Dalai Lama himself. Following his ordination, Wallace joined the prestigious Buddhist thinker Geshe Rabten at the Tibet Institute in Switzerland, where he studied Buddhism, taught courses on Tibetan language and culture and translated for Tibetan Buddhist monks and scholars, including the Dalai Lama. In 1979, he returned to India at the invitation of the Dalai Lama to begin four years of meditative retreats in India, Sri Lanka and the United States, receiving direct guidance from the Dalai Lama on meditative practice and technique.

Consciousness as Reality

At the end of his meditative period, Wallace had been away from Western civilization for nearly fourteen years and decided to re-integrate himself into Western society. Coming to the Pioneer Valley to study with the renowned Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman, who was then a professor of religion at the College, Wallace decided to finish his college education, applying to Harvard Univ. and Univ. of California-Berkeley. However, Wallace quickly adapted to the bucolic scenery of the Happy Valley and chose to continue his education in the area. He applied to the Univ. of Massachusetts-Amherst, but was encouraged his friend and mentor Professor Arthur Zajonc to apply to the College instead. In 1984, Wallace was accepted to the College and began his studies that fall.

During his first semester, Wallace studied mathematics, physics and philosophy, and he excelled in all his classes. Seeking a more challenging program of study, Wallace became an Independent Scholar, an option chosen only by the most disciplined and mature students at the College, where he designed his own curriculum of study, focusing on physics, the philosophy of science and Sanskrit. Wallace used his academic independence to write a groundbreaking two-volume thesis on the relationship between Buddhism, the philosophical underpinnings of modern science and the nature of reality. The ideas he first explored in his thesis drove him to pursue the study of consciousness as a fundamental component of reality.

“The whole notion that the fundamental constituents of physical reality — the elementary particles — do not exist out there with their own definite position, momentum, mass and all that independent of measurement; that is a very strong conclusion of quantum mechanics, and it has very profound implications for our understanding of nature as a whole. It raises questions about what is the role of measurement, what is the role of consciousness and is there a universe without consciousness? You just go deeper and deeper into seeing consciousness as fundamental to our understanding of reality,” Wallace said.

After graduating summa cum laude in 1987, Wallace began leading meditative retreats and publishing books on consciousness, before attending Stanford Univ. and pursuing a Ph.D. in religious studies. Wallace published his dissertation “The Bridge of Quiescence: Experiencing Tibetan Buddhist Meditation” simultaneously with another book, “The Taboo of Subjectivity,” in 1995. Both books dealt with themes of introspection and self-knowledge, approaching them from both Buddhist and scientific perspectives. “The Taboo of Subjectivity” also criticized modern cognitive science for discounting subjective experience as a path to scientific knowledge, drawing on the writings of philosopher and psychologist William James for intellectual support.

“Modern science is stuck in kind of a rut. When scientists want to study the mind, instead of observing the one mind they can observe — their own mind — they forget about that and try to study the mind by studying other people’s behavior and by studying the brain. All of this is very indirect. Everybody knows the brain contributes to mental events, but nobody really knows the nature of the relationship,” Wallace said.

Contemplating Science

Wallace has continued exploring the importance of introspection, founding the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies, an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural research center emphasizing the integration of science with contemplation and self-discovery, in 2003. Wallace is also the director of the Thanyapura Mind Centre in Phuket, Thailand, where he leads intensive meditative retreats and trains people in contemplative techniques. In 2007, he collaborated with neuroscientists and psychologists from universities worldwide in the Shamatha Project, which studied the neurological and psychological effects of long-term meditation and received support from the Hershey Family Foundation and official approval from the Dalai Lama.

Wallace, now perhaps the pre-eminent Western scholar of Buddhism, has transformed the academic careers of many of his students, inspiring them to pursue contemplation and introspection as a path to knowledge. James Elliot, a colleague of Wallace at the Santa Barbara Institute says that discovering Wallace’s ideas was central to his intellectual development.

“Alan has really provided me with a sense of direction. When I first started reading Alan’s work, before I started volunteering with the Santa Barbara Institute, I felt as though I’d finally found something I can dedicate my life to: the interaction and relationship between Buddhism and Science, in my case Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. As I’ve continued to work and study with Alan, this conviction has only grown,” Elliot said.

Although he has faced resistance from many in the scientific community who feel that subjective modes of inquiry such as introspection are less accurate than third-person approaches, Wallace believes that introspection is more in line with scientific values of empirical observation.

“If we look at any other branch of the sciences or even the social sciences, we find that the primary mode of inquiry rests on sophisticated, precise and direct observation of the phenomenon they are seeking to understand. Introspection is the only way we can observe states of consciousness and mental events — thoughts, images, dreams and so forth. Neuroscience ignores this fact. Introspection plays very little role in the modern cognitive sciences, much to their discredit,” Wallace said.

In December, Wallace will enter a six month-long solitary meditative retreat, where he will seek to explore the mind in ways unavailable to traditional psychology and neuroscience, using lucid dreams — dream states in which the dreamer is aware that he or she is dreaming — to perform psychological experiences in ‘dream reality.’ Wallace also hopes to explore subjects often ignored by mainstream cognitive science, such as clairvoyance and astral projection, arguing that dismissing them out-of-hand is no better than accepting them out of faith.

“If [these subjects] are fiction, then let us know that they are fiction. If not, let’s find out what we can discover,” Wallace said. “In meditation, I will be making further discoveries about the true causes of happiness, the true causes of suffering — and of course, without reliance on psychedelic drugs, in which I don’t have any interest. I want to explore alternate states of consciousness. What is dream reality? It opens up some very interesting experiments in consciousness. When you alter your dream reality, you’re working in the perfect laboratory. Nothing is physical; no aspect of your dream is composed of molecules or atoms.”

via amherststudent.amherst.edu

0 notes

Photo

Carlo Ratti: Architecture that senses and responds

via ted.com

0 notes

Photo

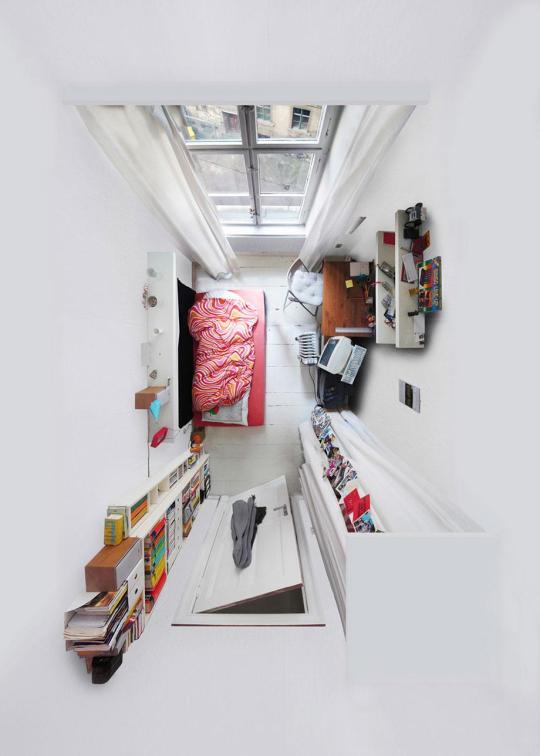

Menno Aden: Room portraits taken from above (PHOTOS).

via slate.com

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Levels House / BAK Architects | ArchDaily

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Architects: BAK Architects Location: Mar Azul, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina Design Team: María Victoria Besonías, Luciano Kruk Collaborators: Nuria Jover, Enzo Vitali Land Area: 600 sqm Area: 187.02 sqm Year: 2011 Photographs: Courtesy of BAK Architects

The location The ground on which we should intervene, forested with maritime pines of great size, has a slope of about 3 m in its front. In connection with the street, one end thereof is elevated while the opposite has a depression that some large acacias hide the view from the street.

Courtesy of BAK Architects

The assignment The order of the client was a house of exposed concrete, to be used much of the year, for a blended family. It was important the social areas to be of a large size, and the master bedroom could function as a sector of great independence and be equipped as not to depend of the rest of the house. It was expressly required the house to have multiple places of saved because the idea is to live there for the three summer months continuously.

Courtesy of BAK Architects

The proposal The particular highlight of the lot, its relationship to the street and the requirement of a large program solved in sectors with some independence, are the issues that make this house a singular one, with a constructive proposal aesthetic, similar to the others built by the studio in Mar Azul.

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Housing was designed resolved into four sectors connected to means levels on a single ladder. This decision allowed us to reduce the circulation areas to a minimum and go accommodating the various uses, following the natural slope of the lot and even burying part of them, reducing in this way, part of the built. The ladder of course becomes the organizer, not only functional but spatial, as a nexus between spaces that need to be integrated. With this volumetric arrangement and taking care to maintain as much vegetation, we were able to provide the house of the variety and flexibility of required spaces, without losing their independent use between them and proposing to them all, a clear integration with the landscape through openings that frame it.

Section

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Courtesy of BAK Architects

Plan

First Floor Plan

Elevation

Elevation

Elevation

Elevation

Section

Section

via archdaily.com

0 notes

Photo

Maryhill Museum of Art Expansion and Renovation Project / GBD Architects | ArchDaily

via archdaily.com

0 notes