Niamh McNulty | 21 | she/they | A diary of foraging for healing and transformation in Scotland

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Enclosed lands

Searching

For week two, I went in search of elderberry. This is because I recently followed Poppy Okotcha, a forager, on Instagram and in the past few weeks she spoke about this plant. She clearly explained how to identify it which gave me confidence to search and refer back to my screenshots if I was unsure. This was helpful because on my previous river searches I didn’t know where to start because I was unsure what to look for.

The first berries I spotted were by the busy t-junction before the river, so were likely unsafe to eat due to pollution. This wasn’t disheartening at first as I thought there would be some further up the river, away from the road and industrial estate. However, the further I went, I couldn’t see any more elderberries, except one tangled up behind ivy and poisonous hogweed. As I walked back through Inveresk, I noticed the Lodge Gardens were reopened, so I thought I would take the chance to see it. Inside were a few elder trees which I picked a small bundle from and made a syrup.

Barriers

Kolmunn and Agyeman (2002) detail what barriers limit people acting sustainably; on my search for elderberry I noticed several. Firstly, time constraints can limit people. For example, if I had taken another course I would be inside reading more often. Next, I lack personal knowledge about foraging. I overcame this by following foragers on Instagram. Books will be useful as I learn more. However, to start instagram offers a mix of video, voice, text and links which feels more rounded. This personal barrier can be linked to an infrastructural one: food identification wasn’t part of my school curriculum. Linking to Kasser’s (2011) discussion of values, the UK is a nation that promotes individualistic values that correlate to engaging in environmentally destructive behavior.

Do our cultural values limit us taking pro-environmental behaviour by prescribing what seems possible, shaping our personal aspirations and infrastructure? Kolmuss and Ageyman illustrate that this may be the case, showing how external factors - like politics and culture - influence our value system and therefore what steps we may take towards learning more about a particular environmental behaviour. Point in case, I have limited knowledge and confidence, but I do have nature-oriented values and access to a university course that allows me to overcome these barriers. They also note how these personal factors - what knowledge and values we hold or how confident we feel about a topic - may direct whether we take indirect environmental action that impacts the wider world.

For example, there was the infrastructural payment barrier to enter the garden. Although not pertinent to me, not everyone can spare money to be around nature. More to the point, the walling off of land once likely owned in common - meaning shared and worked by the community - is part of a history of dispossession from knowledge and literal sustenance (Shiva, 2016). Non-commercial foraging is allowed on National Trust sites. Yet, it still struck me how there was an abundance of food on this private land and over the wall, only roads and monoculture. How can people en masse tend a relationship to nature and food systems when land ownership is unequal? This leads me to see how taking a small, personal action in foraging engages me in considerations about the politics underlying how I am able to engage with it. In time, I feel this must play into the public sphere activism I take towards a Just Transition.

References

Kasser, T., 2011. Ecological Challenges, Materialistic Values, and Social Change, in: Biswas-Diener, R. (Ed.), Positive Psychology as Social Change. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp. 89-108.

Kollmuss, A., Agyeman, J., 2002. Mind the Gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 8, 239-260.

Shiva, V., 2016. Earth Democracy: Justice, Sustainability and Peace, Zed Books: London, *insert page*

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foraging for a more sustainable world

* This post was written as part of my assessed coursework for Responding to Sustainability Challenges: Critical Debates. It was written on October 1st 2020 *

My challenge is to identify more than human life within my locality and to forage one of these a week to include in a meal. I will focus my search in my garden, at the River Esk and the Musselburgh coast.

I am resistant towards making individual lifestyle changes. I feel the mainstream focus on straws and light switches shifts blame from states and corporations to those relatively less powerful and more constrained by wider rules, systems and levels of access. It shows, as Maniates (2001:33) says, “capitalism’s ability to commodify dissent” which limits our capacity to imagine meaningful responses that live up to the challenge at hand. Therefore, my first thought was to engage in public sphere actions where I can have more influence as part of a community.

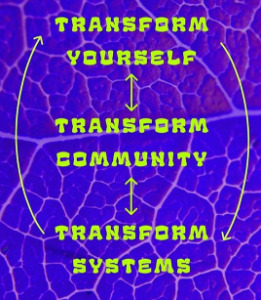

I thought of reflecting on my work with Climate Camp Scotland, a direct action group working against the fossil fuel industry in Scotland and for a Just Transition for workers and communities across the world. A Just Transition is a concept referring to a deliberate effort to prepare for a transition away from carbon economies and to promote socially sustainable jobs (Smith, 2017). The work I do in the group is building conflict processes based within a Transformative Justice (TJ) framework. TJ is a liberatory political approach to different levels of harm that centres safety and healing for survivors, does not rely on state interventions, and seeks to transform the conditions and people that cause harm (Mingus, 2018). I see this as part of social sustainability. Where organising spaces can be emotionally gruelling, risky and force us to confront uncomfortable topics, working on this interpersonal level is important in sustaining public sphere work. TJ has taught me that systems of violence are felt and enacted by each of us; that they seep into our lives. Is this the case with our relationships to the earth? Does that impact how we engage in solution making? What will a Just Transition from ecologically destructive industries look like if we hold an ambivalent relationship to nature?

Image by @ chiara.acu on Instagram

These questions drew me to this challenge. Malm (2013) discusses how fossil fuel production changed time-labour dynamics, throwing them out of sync with earth cycles and into sync with the drive for profit. It feels as though most of our waking hours are directed by demands of our employers, leaving us little time to think of what food we put in our mouths and how to care for our loved ones. Nevermind having the time to know nature. Before lockdown, I only walked back and forth on the same route to the bus stop. During lockdown, I was able to explore. I couldn’t name any of the plants. What I thought were dock leaves weren’t; what I thought were elderberry, were common ivy. This vast disconnect became so clear. Why am I spending hours in meetings and at protests if it is not to retain, rebuild and transform our relationship to each other and the earth?

I hope that naming and eating foods from my locality will help me tend a relationship with my environment rather than being insulated from it. I hope it directs me to taking effective public sphere action by letting me see not only what I am fighting against, but how to transform the conditions that allow the climate crises by healing my relationship to earth.

References

Image by @chiara.acu

Malm, A. 2013, 'The Origins of Fossil Capital: From Water to Steam in the British Cotton Industry’, Historical Materialism, 21(1), 15-68

Maniates, M. 2001, ‘Individualisation: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?”, Global Environmental Politics, 1(3), 31-50

Mingus, M. 2018, ‘Transformative Justice: A Brief Introduction’, Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective [online], Available at: https://transformharm.org/transformative-justice-a-brief-description/

#foraging#scotland#transformative justice#just transition#plant healing#climate justice#environmentalism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cayr

'To return to a place where one has been before' (Thomson, 2018)

Welcome to this space where I’ll be writing about my journey foraging around my home in Scotland.

I began this project after completing a blog assignment as part of my degree in Sustainable Development with Politics and Internal Relations at the University of Edinburgh. My thanks go to Dr. Rachel Howell who organised the course ‘Responding to sustainability challenges: critical debates’ for creating the space that allowed me to take up foraging and think deeply about it. The first four posts here cover the coursework I submitted. This space is dedicated to continuing the lessons I was beginning to learn there.

Hopefully writing here encourages me to take the time to step outside, learn the names of plants and animals, and build a connection to earth and community. Though I’ve lived in Scotland my whole life, in many ways I feel I have never been truly present in this land. I chose the name Cayr, a Scots word, to represent this homecoming.

References

Thomson, A. 2018. A Scots Dictionary of Nature, Saraband: Glasgow, p.199

#Scotland#foraging#scots language#nature#nature writing#sustainable development#climate justice#edinburgh

2 notes

·

View notes