Link

Get Out of the Car acts as a prompt to reconsider the cultural legacy of specific vanished places, and as a call to action to be vigilant of existing structures that could be on the verge of similar ‘redevelopment’.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

“When you post or publish a photograph, that means it has something special [to you]” says Caballero. “But with main details—we found them in those pictures that were not special, you know, the ones that are out of focus or that it has a strange angle. There’s a lot of details there that inspired us on how to do the decorations.”

0 notes

Link

“The landscapes serve as a kind of evocative wallpaper where you can project your own associations. I think the shots exude their own qualities of inherent melancholy and loneliness simply due to the lack of human figures but for me these spaces also represent a kind of existential empty slate where each viewer can be alone with their own impressions.“

0 notes

Link

The Berkeley Graduate Division published my essay which speculates on film’s relevance as a method for understanding and designing urban landscapes. Check it out!

0 notes

Link

Charles Birnbaum (The Cultural Landscape Foundation) on Dan Kiley’s landscapes as featured (but not credited) in Kogonada’s Columbus (2017).

0 notes

Text

Dumbarton Oaks “How Designers Think” colloquium: Narrative Response

November’s How Designers Think colloquium at Dumbarton Oaks featured dynamic presentations from a diverse group of mid-level practitioners in Landscape Design. Some of the most unique voices in today’s discipline shared personal strategies for addressing the increasingly complex and expanding notion of landscape. All of the presenters shared anecdotes and incites regarding projects that encompass the shifting scales, temporalities, and populations. Perhaps more unexpectedly, the presentations contained myriad references to the cinema, a realm that is becoming increasingly relevant to the work of a landscape designer.

At many points throughout the colloquium, a speaker would show a film still or deliver an anecdote to illustrate a point. Suddenly, a discernible and enthusiastic wave of agreement would spread throughout the audience. Many presentations made use of a film to introduce or illustrate a particular landscape. In speaking about the Chicago Riverwalk, Gina Ford of Sasaki Associates acknowledged that the area was regularly portrayed in Hollywood movie trailers. In speaking about Sasaki’s work in the Lower Mississippi River Delta, Ford referenced Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) as a way to render the cultural and ecological embedded within the landscape.

The Chicago Riverwalk as featured in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008)

The Lower Mississippi River Delta as featured in Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012)

Other designers used examples from film to illustrate the concept for a project. Sara Zedwe of GGN showed an image from Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964) to illustrate the ephemeral and formal qualities of fog. Walter Meyer of Local Office referenced the economic circumstances portrayed in The Big Short (2015) in an attempt to describe a design project predicated on ecological disturbance theory.

Fog as represented in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964)

Film was also discussed for its role in shaping the way people understand the landscape we inhabit. Flemish designer Bas Smets of Bureau Bas Smets believes that landscape cannot be seen without the mediation of an artist. In his presentation, he remarked that filmmakers and landscape designers are similar in that neither actually produces landscape. Rather, they both produce images of landscapes. Smets, interested in the intersection of film and landscape design, elaborated on a project in which his firm collaborated with an esteemed filmmaker and cinematographer to produce a landscape “that can only exist on film” (Continuously Habitable Zones, 2011).

Cinematographer Darius Khondji filming onset Continuously Habitable Zones (2011)

While some speakers may have not made explicit filmic references, their presentations revealed many interesting parallels with the ways in which filmmakers operate. Both Aki Omi (studio ma) and Michelle Delk (Snohetta) discussed the importance of narrative(s) in their work. Omi implored designers to reveal a story about the site rather than trying to be an expert of culture. Similarly, in film, it is often the fresh eyes of an “outsider” director or cinematographer who is able to find a narrative and give a landscape its voice.

It is evident that motion picture is becoming a beloved source of knowledge and inspiration among designers. Functioning to bridge understandings across cultures, film has a special role in mediating the way we perceive and discuss ideas and landscapes. In his presentation The Real and the Marginal, Jose Castillo of arquitectura 911sc enthusiastically argued that designers should not be afraid to be emphatic. In order to push innovation within the discipline and in society, it is necessary to dream big, much like the protagonist in Werner Herzog’s epic Fitzcarraldo (1982) who manages to drag a steamboat over a steep forested hill in the Amazonian Rainforest.

Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982)

#Dumbarton Oaks#How Designers Think#Sasaki#GGN#Snohetta#Bureau Bas Smets#arquitectura 911sc#colloquium#recap#landscape design#Landscape Architecture#cinema#landscape film#studio ma#Local Office

0 notes

Link

“Whereas we landscape architects make images that we transform into reality, filmmakers create a reality that then produces images. The two approaches create a cycle of reality, transformed into images while transforming reality. It’s an endless cycle, just like the seasons.”

I had the opportunity to attend the “How Designers Think” colloquium at Dumbarton Oaks yesterday. There was not a single lecture that did not at one point allude to film. Flemish Landscape Architect Bas Smets (Studio Bas Smets) gave a fascinating lecture in which he spoke about a landscape he created specifically to be filmed (elaborated on in the above article), and reflected on this implications of this in regard to the role of today’s landscape designers.

0 notes

Link

“Indeed, Benning’s excess spawns a musicality – manifested in the rhythm of landscape – that affects the viewer supra-emotionally... If Benning shares their languid sense of rhythm, indeed, it would seem to be demanded not only by his subject matter, but further by what the director intends to accomplish in the film. Specifically, Benning’s stated purpose in 13 Lakes is to make a film that assists his viewers in becoming artists. Again, the temporal dimension of the work facilitates this strategy as the extended duration provides the viewer with the opportunity to decipher small changes and fluctuations in the natural world. In other words, it impels the viewer to look and listen with greater sensitivity, which importantly mimics the name of a class he teaches to young artists at the California Institute of the Arts, “Looking and Listening”. Both represent the same programme of honing the sensorial acumen of would-be artists. Ultimately, 13 Lakes and his class both attest to the same belief: that being an artist, especially in the cinema, is first a matter of being sensitive to the surrounding world. To see and to hear are necessary preconditions of being a successful artist.”

0 notes

Link

“How do I read a landscape? How do I stage a landscape? How do I direct a landscape? Yes, you can direct human beings, you can direct animals, and you can direct landscapes to a certain degree.”

0 notes

Text

Objects and Meaning in the Landscape

The chair in which Don Pietro, priest, meets his fate for colluding with anti-fascists during the nazi occupation of Rome.

Rome, Open City. Roberto Rossellini (1945)

Monument in memory of deported Norwegian Jews. Antony Gormley. Akershus Fortress, Oslo, Norway.

“The Holocaust cannot be represented. I want to make a place to remember, to make a bridge between the living and the dead in order that these events and their implication should not be lost. The site is very evocative with the most minimal intervention. The presence of the excluding walls of the fort and the sea are already very powerful imaginative catalysts. The trees act as a witness to time and its passing.”

http://www.hlsenteret.no/gormley/english.html

Photos by Gene Stroman, film, 2017

#Rome Open City#Rossellini#Landscape#Cinema#Landscape Design#Sculpture#Meaning#Cultural Landscape#Oslo#Antony Gormley

0 notes

Text

DREAMING RENO: Film as Transect

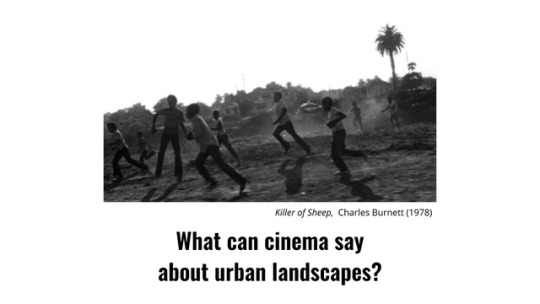

People have ways of assigning meaning to what they perceive based on atmospheric qualities which can be difficult to record with traditional means of architectural representation, for example the plan or section drawing. Film is a medium more ideally suited for picking up on the nuances of a built environment that may be interesting or relevant to the gaze of a mobile pedestrian.

In Landscript 2: Filmic Mapping: Film and the Visual Culture of Landscape Architecture, film scholar and curator Fred Truniger asserts the facility of motion picture to capture the pedestrian gaze, or the way in which one reacts to atmospheric stimuli as he or she wanders through an urban environment. Truniger summarizes philosopher and urban theorist Guy Debord’s early experiments in psychogeography in which Debord attempted to systematically map the phenomena of walking perception by overlaying subjective, qualitative information over traditional forms of 19th-century cartography. While Debord’s exercise was certainly innovative for its time, expanding on classic methods of cartography, his own methods were still deficient in their attempt to map a hyperactive, yet selective gaze in a dynamic urban environment. “The pedestrian’s gaze is never disinterested; ambulant perception constantly absorbs meaning,” writes Truniger (130).

Truniger continues to argue film’s suitability for translating the way in which people make sense of their environments: “Selection and interpretation -- in other words, the fragmentariness inherent to perception -- is translated in film using montage, which in itself is actually the organization of fragments. The way attention is guided by montage corresponds to the guiding interest of a gze not tied to a place. The filmic cut also offers a parallel to the interpretive perception of real space, in which everyone focuses his attention on different things depending on his (visual) preferences and fixations, and puts other “landmarks” in the foreground: whereas for one person, a notable building in the central experience in “her landscape”, for another it will be a chance encounter on a simple park bench. The film has already made the choice between these options and it compels the viewer to an entirely specific, pseudo-individual perception. Unlike walking in reality, there is in the cinema (in most cases) no “outside” that the viewer could alternatively consider… The filmic montage is thus an instrument for relating the fluctuating experiences of routes taken” (131).

DREAMING RENO (2017), utilizes filmic representation to pick up on place-defining attributes of the landscape in Reno, Nevada, a city filled with surreal, dreamlike environments, layered histories, juxtaposed heteropias, and leftover monuments from the city’s many eras of prosperity. The film follows the wandering gaze of two visitors on their first trip to Reno and depicts three separate transects (1) casino, (2) alleyways, (3) desert related to the cultural perception of Reno.

vimeo

DREAMING RENO: Casino Transect (Stroman, Dominguez, 2017)

Created during the preliminary site investigation phase of a project to strategize the reanimation of Reno’s downtown, the film was made without any preconceived notion of what our strategy might be. However, after recording and editing the footage, our concept became immediately clear: utilize Reno’s vacant alleyways to create an alternative way of experiencing the city.

vimeo

DREAMING RENO: Alleyways Transect (Stroman, Dominguez, 2017)

Using film, we were able to translate qualities of Reno’s built environment that were striking to a first-time visitor, for example the dancing reflection of a metallic panel across the worn paint of a derelict, but eerily beautiful alleyway or the overlaying of naturalistic sights and sounds in highly artificial environments like a casino. The use of filmic montage and non-diegetic sound were essential to relay the eccentricities of a place like Reno to an audience.

vimeo

DREAMING RENO: Desert Transect (Stroman, Dominguez, 2017)

Film has the potential to transform people’s perception of a place, and the goal of DREAMING RENO is to redefine Reno’s quirky (often perceived as trashy, ugly, tasteless, lacking culture, etc.) built environment as an asset for the city -- one that could serve both citizens and visitors by making sense of the city’s disparate histories and creating an alternate system of public spaces ideal for wandering and exploring the palimpsest that is Reno.

DREAMING RENO is a short film made collaboratively by Gene Stroman (MLA 3D) and Daniel Dominguez (MLA 3D) for LA 202 Drawing the Desert Studio (UC Berkeley, Spring 2017, Instructor: Danika Cooper). The full film can be viewed here.

#Stroman#Dominguez#Dreaming Reno#UC Berkeley#Landscape Design#Landscape Cinema#Landscape#Cinema#Palimpsest#Casino#Desert#Alleways#Reno

0 notes

Link

Last week, I had the opportunity to see the restoration of Andrei Tarkovksy’s Stalker at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. The characters’ dreamlike journey through the abandoned, lush, and ruderal landscape of “the zone” immediately brought to mind images from my childhood, and the joy of exploring the overgrown creeks and woods that ran behind suburban Northern Virginia.

What is the “zone” in Tarkovsky’s film? Knowing very little about this filmmaker, aside from the fact that he was (surprisingly) an Orthodox Christian, my interpretation is that his film is about finding a place (in your mind, and perhaps in the built environment) in which you can experience the world around you without scrutiny and without fear, just like a brazen young boy making his way across the weed and detrius-strewn landscape of youth.

0 notes

Link

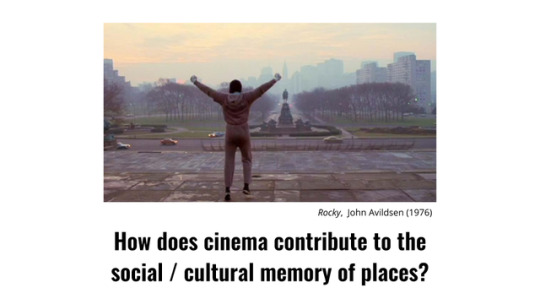

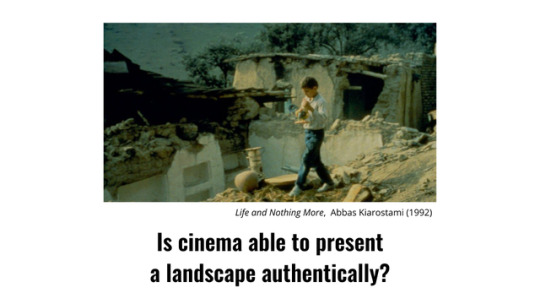

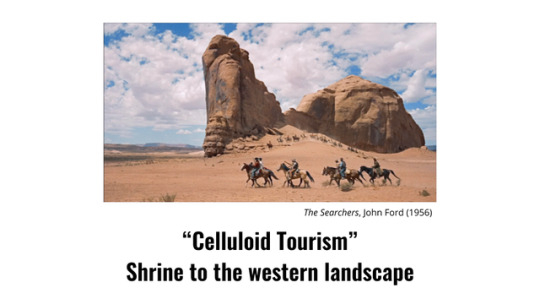

A film categorized as a “Landscape Film” is more than just a film that features a city or landscape as a main character. Just as landscapes are integral to the shaping of our thoughts and feelings over time, celluloid landscapes can be formative in the character and narrative development within these films. Landscape Directors, as I call them, for example Antonioni, Malick, or Kiarostami, have a stylistic tendency for shooting environments in a certain light, angle, or composition. This allows the landscape to coalesce with the characters, images, and memories in the mind of the audience–shaping the way we perceive and rationalize the built environment we inhabit.

0 notes

Quote

Of course the openness to interpretation of things that you perceive with your senses is sheer utopia. But at the same time you need to insist on it, as a kind of utopia. If you can’t hang on to it as an ideal, dream, utopia, whatever, then you lose your desire for it and your interest in it. And it's a cinematic ideal, telling a story purely through the senses. But as soon as you have a story - and with an epic story, it's still harder - you get that split. Storytelling itself is a cerebral undertaking. There's no getting round that. It’s to do with proofs and dramaturgy, and very soon the ideal of a purely sensual narrative is just that: an ideal. But that's the force field in which every film has to exist.

Wim Wenders, The Truth of Images

Can landscapes unfold like a story? To what degree can landscape designers tell a story purely through sensory experience? Should a landscape be curated for a user to experience in a particular way, or should the landscape produce memories and stories through pure interaction?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

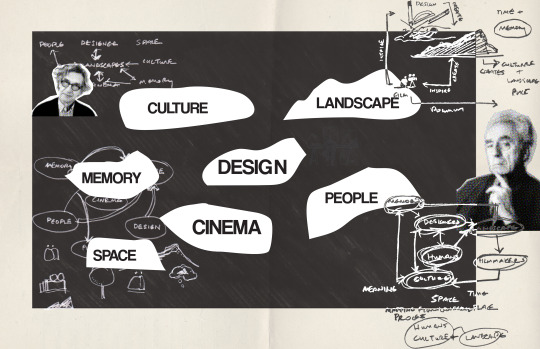

Slides from our final presentation to the ARC Fellows on April 11th, 2017.

#ARC Fellows#Arts Research Center#Spring 2017#University of California#UC Berkeley#Landscape#Film#Landscape Design#Landscape Architecture#Chip Sullivan#Gene Stroman

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Mapping the relationship of film and landscape, Gene Stroman, 2016

#ARC#Arts Research Center#University of California#UC Berkeley#Chip Sullivan#Gene Stroman#Film#Landscape#Celluloid Landscape#Landscape Design

0 notes

Text

Dreamscapes

Channeling dreams to create new worlds

Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky (1979)

In Chip Sullivan’s new book, Cartooning the Landscape, he argues that anything is possible during dreams and that this wellspring of creativity should be utilized by designers to generate unique and innovative landscape typologies. Dreams can also provide a space in which environmental designers can test and execute design concepts free of constraint. In a section titled Dreaming the Landscape, Chip illustrates the power of recording and translating our dream states, and includes examples from contemporary landscape designers such as Randy Hester, Cheryl Barton, and David Meyer.

Dreams are also an integral part of cinema, and the term “dream factory” has long been used as a metaphor for the film industry -- a laboratory for filmmakers to test and recreate worlds that are free of earthly limits. Much has been written about the similarities between the world found in our dreams and the world depicted on screen. Many filmmakers including David Lynch, Jean Cocteau, and Andrei Tarkovsky have garnered reputations for their ability to construct environments that exist in this hazy realm of the unconscious. Even Alfred Hitchcock worked with surrealist painter Salvador Dalí to design and film a dream sequence for his 1945 feature Spellbound. Hitchcock and Dalí utilize elongated shadows, fog, skewed camera angles, experimentation with scale and other surreal elements to create a landscape of warped time and perception.

youtube

Dream sequence from Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), featuring set design by Salvador Dali, the surrealist known for his unique depiction of dreamworlds.

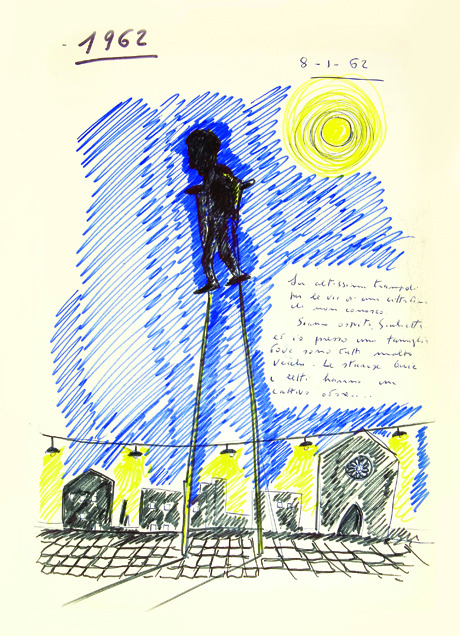

Fellini on set at Cinecitta

Italian director Federico Fellini has been celebrated for his dreamlike style of filmmaking which found its way into each of his films over his five decade career (~1945-1992). Many of his films include circus-like elements which lend to an artificial atmosphere that is just a step beyond reality. The inspiration for the Fellini’s films came directly from his dreams. In 2008, Rizzoli published the director’s dream notebooks, a treasure trove of recorded dream sketches and descriptions that the director (inspired by the work of Carl Jung) kept by his bed beginning in the early 1960s. These notebooks are beautifully illustrated and fascinating for their direct connection with the dreamscapes Fellini featured in some of his best films from his oneiric period, for example 8 ½ (1963), Juliet of the Spirits (1965), Amarcord (1973), and Casanova (1976).

From Fellini’s Brook of Dreams (Rizzoli, 2008)

youtube

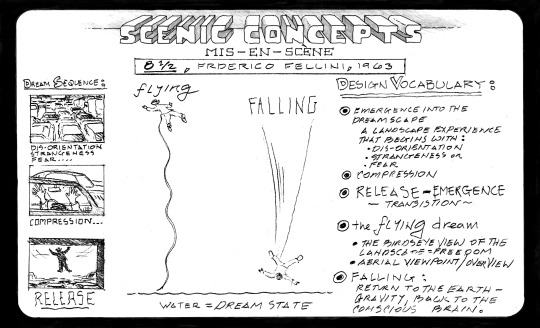

Opening dream sequence from Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963), one of the most important films of all time which straddles the line between dreams and waking life

Scenic Concepts: Dream Sequence from 8 1/2. Chip Sullivan, 2017.

In a piece titled Amarcord: Federico of the Spirits, Sam Rohdie, professor of cinema studies at the University of Central Florida, discusses Fellini’s 1973 feature Amarcord (I Remember) as an example of Fellini’s later films, which marked a departure from dramatic, realistic, or traditional narrative structure in turn for a more intuitive, dreamlike cinema:

In Amarcord, the Rex is made of cardboard, the sea of plastic, the sunset of paint. Very little is natural, and when it is, it is parodied and deformed. The natural was not an opportunity for Fellini, material to be recorded or rearranged, but rather a constraint, like rationality, defined order, and logic were—a limit on his creativity—and that is why the natural, the narrativized, and the realistic began to disappear from Fellini’s work, at first imperceptibly, before 1960, and then markedly afterward.

Rohdie goes on to describe how this exploration of a stylized dream world helped the director to innovate new, more ephemeral themes:

Being freed from the constraints of narrative allows not only for a greater range of associations but for filmmaking in which images and sounds and their colors, textures, light, tones, rhythms, and movement can combine and resonate. And in Fellini’s case, these are resonances of joyfulness and generosity.

Fellini’s body of work and the history of motion picture include countless successful examples of dreamscapes that have proven to be popular among audiences across the world. Dream sequences have made their way into cultural memory, becoming archetypes that are constantly analyzed and replicated. Environmental designers should consult these dreamscapes in order to think differently about the fundamental design tools of our trade, for example scale, material, experience, and the more ephemeral or sensory qualities of a landscape like light, sound, and smell.

1 note

·

View note