茶の湯とは只湯を沸し茶を立てて呑むばかり成る本を知るべし (千宗易・利休居士)["With respect to chanoyu, just make the water boil; and after the tea is prepared, simply drink it: this is the fundamental idea upon which we should act, you must understand." (Sen-no-Sōeki, Rikyū Koji)] Ask Chanoyu to wa a question

Last active 3 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Very Brief Update -- and a Request for Your Input, Please (8/21).

Professor Ahn just left. We were able to take excellent photos of all of the chaire kiri-gata. So a big shout-out to him, and thanks for his work and help!

The next step will be to process the photos (crop the white borders, make them all a uniform size, and so forth). I guess that will take a day or two (it is a little late now to accomplish more today, so I will begin working on them tomorrow morning). Once the photos are processed, I will have to decide what to translate (many of the kiri-gata do not have much of anything written on them, so there will be nothing to translate in those cases), and also how to format the post. I will also have to search for photos of the actual chaire represented by the kiri-gata. While I am sure that they are all in Takahashi Sōan's Taishō mei-ki kan [大正名器鑑], more recent photos would probably be a better option on account of their clarity (and the fact that they would be in color, which most of his photos are not). I am not sure how long the search will take.

What I can say now is that this project will probably have to be spread across either two or three posts (depending on how much text there is) -- though even that will remain uncertain until I actually start to create the posts.

Feedback would be very helpful at this point, so please let me hear from you. You can use the "ask" feature, and you can send your suggestions anonymously if you prefer (I have enabled both options). Or you can write to me by e-mail, in care of the address below my signature.

Thank you all for your time, and for your suggestions. Please have a good day.

-- Daniel M. Burkus [email protected]

Donations: https://paypal.me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part V: Poem 113.

〽 Rikka nado yorite kenbutsu-suru-toki ha ōgi wo nukite yorite miru-mono

[立花などよりて見物する時は 扇を拔てよりて見るもの].

“Because there is a rikka [立花], or something of that sort, when [approaching] to inspect [the toko], only once [the guest] has taken out [his] fan should [he] then [proceed to] look at what has been displayed.”

Rikka [立花 or 立華] is a formal floral arrangement that, in its most conventional form, was intended to represent an idealized landscape¹.

A sketch of a rikka, by Sōami [相阿彌; ? ~ 1525] (the grandson of the great Nōami [能阿彌; 1397 ~ 1471], and son of Nōami’s successor Geiami [藝阿彌; 1431 ~ 1485])², the author of the O-kazari ki [御飾記], composed of the three elements shō or matsu [松] (pine tree), chiku or take [竹] (bamboo), and bai or ume [梅] (flowering plum) -- the suì-hán sān yǒu [歳寒三友] (sai-kan san yū in Japanese), which means Three Friends of the Cold Season³ -- is shown above.

Rikka nado yorite [立花などよりて] means “as a consequence (yorite [依りて, 因りて]) of the rikka [立花], or other things of that sort (nado [など]⁴)....”

Kenbutsu-suru-toki [見物する時]: kenbutsu-suru [見物する] means to view, to inspect⁵, so kenbutsu-suru-toki ha [見物する時は] means “when inspecting (the rikka or other things of that sort).”

Ōgi wo nukite yorite miru-mono [扇を拔てよりて見るもの]: ōgi [扇]⁶ is the folding fan; the verb nuku [拔く] means “to take out” (for example, extracting the fan from one’s obi, or drawing or unsheathing a sword from its scabbard); yorite [依りて, 因りて], as above, means “as a consequence of (having done something),” or “after (he) has done something;” and, miru-mono [見るもの]⁷ means things to see, what there is to see.

Putting these ideas together, we understand Joo to be saying that only after the fan has been taken out should (the guest) look at whatever it is that has been displayed. Note that, in Jōō’s period the act of “taking out one’s fan” meant that the fan was to be opened and held in front of the face. Putting it down on the floor to create some sort of “virtual wall” to separate the guest from the object that is going to be examined is a rather meaningless gesture.

The reason why the fan is held in front of the nose is because rikka arrangements are very complicated, and if the exhaled breath caused some of the flowers to become disarranged, this would spoil the effect. Rikka were typically arranged in the toko of the large rooms, wile arrangements that we would identify as “chabana” were displayed on the chigai-dana, or on the dashi-fuzukue [出し文机], the built-in writing desk in the shoin room (this desk is often referred to as the tsuke-shoin [付け書院] today). And the reason why the tea schools abjure this action today appears to be because certain ikebana schools teach that it should be done⁸.

The version of this poem archived by Katagiri Sadamasa seems to be a revised (and so more inclusive) version of the original⁹:

〽 nani-shite mo hana wo haiken-suru toki wa¹⁰ sensu wo nukite yorite miru-mono

[なにしても花を拜見する時わ 扇子をぬきてよりて見るもの].

“Whatever sort of flowers you are inspecting at the time, take out [your] sensu and [only] then look at whatever it is [that has been displayed for you to appreciate].”

Nani-shite mo [なにしても] means things like “no matter what,” “whatever (they are),” “in any case,” and “regardless.” In other words, irrespective of the kind of flower arrangement (whether it is a more formal sort of arrangement created according to the rules of ikebana, or whether it is a case where the flowers have simply been “thrown into” the hanaire casually)....

Haiken-suru [拜見する] is the verb for to inspect, to look at, to view, that has been come to be preferred over kenbutsu-suru [見物する], in chanoyu, since the Edo period.

In chanoyu, sensu [扇子] has supplanted ōgi [扇] in general use since the beginning of the Edo period.

So, aside from the fact that this version has broadened the types of floral arrangements about which the poem is speaking, the meaning is basically the same as we find in Jōō’s Matsu-ya manuscript version.

_________________________

¹An idealized landscape that was technically intended to represent, or invoke the Buddha Amida’s Pure Land (as described, for example, in the Lotus sūtra).

²Together the three -- Nōami, Geiami, and Sōami -- were known as the san-Ami [三阿彌], on account of their inestimable influence on the courtly arts during the second half of the fifteenth century, and on into the sixteenth century (and beyond).

³Suì-hán [歳寒] (sai-kan) literally means the cold (months) of the year, so suì-hán sān yǒu (sai-kan san yū) is often translated “the Three Friends of Winter.”

In Japan they are used as a symbol of the New Year’s season because the Lunar New Year occurs around the time of the “official” end of winter (symbolized by setsu-bun [節分], the parting of the seasons, on February 3rd or 4th).

⁴Rikka nado [立花など] means rikka and other things of that sort.

This “things of that sort” appears to be referring to things that were formally arranged in the toko* (such as the oshi-ita kazari [押板餝] shown above in a sketch from Sōami’s O-kazari ki†)

As mentioned above, the intention behind this kind of arrangement (the scroll or scrolls, the “landscape” floral arrangements, and incense to perfume the air) was to create a stylized vision of Amitābha’s Pure Land. __________ *The implication seems to be that the action described in this poem -- taking out the fan with the intention of covering one’s nose (so the breath will not disturb the things that one is inspecting) -- might be unnecessary when looking at more casually arranged things.

The verb-construction used to describe the mechanics of arranging an “ordinary” chabana is nage-ireru [投げ入れる], which literally means “thrown in” or “dumped in together” -- that is, the flowers should be arranged without any show of artifice. (That said, even such arrangements should be inspected with the fan in front of the nose when composed of grassy flowers -- plant material that can easily be disarranged by the slight breeze resulting from an exhaled breath.)

†In this arrangement, a rikka of the sort shown in Sōami’s painting (in the body of the translation) was supposed to be arranged in each of the flower vases placed on the two sides of the arrangement. These rikka would be constructed as mirror-images of each other, that would be focused toward the incense burner (in the center of the arrangement).

⁵Today, the world of chanoyu prefers the expression haiken-suru [拜見する], which is a more formal way of saying exactly the same thing.

⁶Sensu [扇子], which we usually use in chanoyu, is an alternate form of the same word.

⁷Cf. kenbutsu [見物], which has essentially the same meaning of something to see (and so is also used to name the act of sightseeing, as well as to describe things that we would call a spectacle, a sight-worth-seeing, an attraction).

Miru-mono [見るもの] is conventionally written without the second kanji, to avoid any verbal confusion with kenbutsu.

⁸In other words, the rules for chanoyu must be different from ikebana -- an excellent example of the Edo period nonsense that resulted from the separation of the different arts from each other -- this despite the fact that Rikyū was the “master” who was charged with creating the rikka arrangements for Hideyoshi’s reception rooms.

In which capacity, Rikyū invented a new sort of flower shears that have a rounded tip (because Hideyoshi objected to the presence of even a small knife in his rooms -- which had been the usual implement for cutting the stems of the flowers theretofore).

These shears are, unsurprisingly, known as Rikyū-basami [利休鋏]. Their use is forbidden by the tea schools, however, because chanoyu must be different from ikebana.

Apotheosize Rikyū as the God of Tea, and perform rites and ceremonies to his memory by all means; but it is “unprofessional” for someone to be involved with more than one art*: ignore (or even denigrate) what he actually did or taught. This appears to have been the guiding principal of chanoyu since the Edo period. __________ *Given the definition that has held since the Edo period, it becomes necessary to ask, was Rikyū a “professional” chajin? Did the profession of chajin even exist during his lifetime? Was it even a business at all?

The Japanese say that a professional is supposed to be dispassionate about his art (to the point, apparently, of having no personal interest in it at all beyond what will bring in the maximum profit); but Rikyū appears to have been unusually passionate about chanoyu. And he was as proficient in flower arranging, and incense, as he was in tea. Ergo he must not have been a professional at anything.

Sometimes crude ignorance manifests itself in curious ways, such as in this approach to “professionalism.”

I know I have come down on this before, but this is really my pet peeve with the state of things. Indeed, it is, I believe, the reason why chanoyu in Japan has degenerated into little more than utensils (as financial investments -- or ways to hide money) and food. And since the whole system appears to be breaking down (as a result), I cannot imagine that there is much that can be done to salvage things there. Unfortunately, however, this “approach” is also spreading among tea people in other countries, and that is to be regretted -- and avoided in so far as it is possible. Forget about the monetary aspect of tea. Make chanoyu a part of your life as much as you can. Participate because you enjoy it, and serve tea to your guests with utensils that appeal to you. And when you are the guest, look at the utensils and try to understand what the host sees in them; and forget about who the maker was. In that day, nobody knew -- or cared -- who Chōjirō was. Newly made pieces were easy to replace, and used as such -- so it was only the interest that the utensils themselves provoked that made them memorable. Ideally, it should be something like that....

⁹Though the problem is -- by whom.

The changes seem better to reflect the sensibilities of the Edo period, rather than Jōō’s day -- especially regarding the word rikka [立花], which, by the Edo period, had become inexorably fixed to the art of ikebana, meaning it would not be acceptable to find it in a poem about chanoyu.

¹⁰Most curiously, the person responsible for this version has written the kana wa [わ], rather than the particle ha [ハ or は]. In other words, the kami-no-ku [上の句] (the first “half” of the poem) should read: nani-shite mo hana wo haiken-suru toki ha [なにしても花を拜見する時は].

This might suggest that someone other than Jōō undertook the reconfiguring of this incarnation of the poem,

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

❖ As the international exchange rate continues to collapse, your help is even more necessary than heretofore, since this blog is my only source of income. Please donate, if you can.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Chaire Kiri-gata [利休茶入切型], Part 2.

[Returning to] this kiri-gata [of the Nitta-katatsuki], the inscription reads, “an orange-red [color] appeared on the nadare during firing²⁶.”

In the Tennōji-ya kaiki [天王寺屋會記] (Sōtatsu ta-kaiki [宗達他會記]²⁷), in an entry for the 17th day of the Fourth Month of Tenbun 19 [天文十九年卯月十七日] (1550), in which [Sōtatsu] describes the physical details²⁸ of the Nitta-katatsuki (which was, at that time in the Ōsaka-Kyōto area²⁹), it says: “at the edge of the nadare streaks -- on both streaks -- an orange-red [color] appeared during firing” (nadare no suji no fuchi ni, futa-suji nagara, shu wo yaki-dashi sōrō [なたれのすちのふちに、二筋なから、しゆをやき出候])³⁰.

Tsuda Sōtatsu had a discerning eye, so every detail of [his] description matches exactly [the actual appearance of the chaire]. This being the case, it [might] lead to the conclusion that it was not Sōtatsu, but rather his son Sōkyū who wrote these notes [on the kiri-gata] -- though there is no way to know for sure. We must also remember that there was a close relationship between the Tennōji-ya [house] and the Ōtomo clan³¹.

In the end, while the possibility of the Rikyū chaire kiri-gata being created by Rikyū remains, there might be a stronger likelihood that they were Tsuda Sōkyū’s chaire kiri-kata [which are occasionally mentioned in documents from the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries].

This is not to say that there is no connection between Rikyū and the [concept of] kiri-gata, however. During the Tenbun [天文], Kōji [弘治], and Eiroku [永祿] eras, when the tea ceremony was flourishing in Sakai, [many] machi-shū were actively cultivating their expertise in judging the utensils used for chanoyu -- and Rikyū, as he was approaching his prime, spent his years immersed in this environment. Which is to say that the impetus was certainly there for Rikyū to also create his own kiri-gata³².

This kind of [tactile] approach may have, in turn, played a role in Rikyū’s activities of not so many years later³³, when Rikyū began guiding Chōjirō [長次郎; 1516? ~ 1592?] in the development of the ima-yaki chawan [今燒茶碗]³⁴ (Raku-chawan [樂茶碗])³⁵. Furthermore, in the Ninth Month of Tenshō 15 [天正十五年] (1587), Yoshida Kanemi [吉田兼見; 1535 ~ 1610]³⁶ asked [Rikyū’s disciple] the Tōyō-bō [東陽坊]³⁷ to help him seek out one of Rikyū’s kiri-gata³⁸ from the kama foundry at Sanjō (located several blocks east of Hideyoshi's Nijō castle compound) -- this is another example that we should consider.

So, here, in Yonehara Masayoshi sensei’s essay, we have read that there is some reason to doubt whether the Rikyū chaire kiri-gata were actually cut by Rikyū, or by someone else -- one of his contemporaries. This is hardly unique, in Rikyū’s history. Many of the most famous stories about Rikyū, and (perhaps even more so) his chanoyu, do not stand up to scrutiny. After his family lost their fortune, he was able to recover, to be sure, but after Jōō’s death the backlash from the tea world drove him into a sort of self-imposed semi-retirement. He rose up again, because the simplicity and rationality of his style of chanoyu impressed the greatest military minds of that day; but even under Hideyoshi, his influence remained limited to Hideyoshi’s inner circle. And because of this, his fall came fast, and the limits on his influence lead to the rapid fading of his legacy, to be supplanted by the teachings of his greatest rival. And when it became expedient that Rikyū become a combination of national teacher and virtual God of Tea, his general lack of history made it easy for the teachings and anecdotes of others to be transferred to glorify him, and his descendents.

But as for the chaire kiri-gata themselves, even if they were actually cut by a hand other than Rikyū’s, they still provide us with a wealth of information that could be gathered only by someone who had held those famous chaire in his hands, cut their silhouettes, and then recorded their details for his own edification -- and our own.

_________________________

²⁶Nadare ni shu wo yaki-dete [ナダレニシュヲヤキ出].

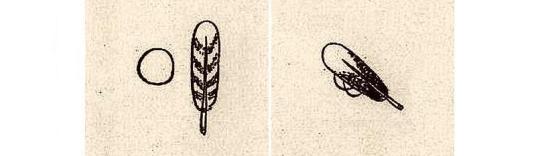

Nadare [雪崩] -- the kanji-compound literally means an avalanche of snow (which this sort of glaze effect resembles) -- refers to a run of glaze that occurs during the glazing process. There are two ways this can occur (naturally*). The first is when the glaze is especially watery, this may occur immediately (as we see on the left); or it may run as the glaze begins to vitrify during the firing process (as in the middle example), in which case the nadare appers within the glaze). These effects are seen on many of the karamono-chaire, and in this case, the effect was purely accidental (since these pieces were produced for utilitarian purposes, so the only really important features were that their sizes and shapes be identical, whether made as medicine jars or containers for souvenir liqueurs or hair pomade).

The other is when a drop of glaze accidentally drips down from a piece that was loaded higher in the kiln, or else natural ash glaze that sometimes collects on the ceiling of the kiln drips down onto the pieces below. Particularly in the latter case, this often results in the nadare being colored differently to the rest of the glaze on the piece (as seen in the example on the right).

Nadare ni shu wo yaki-dete [ナダレニシュヲヤキ出] means an orange-red color appeared† on the nadare during the firing process‡. It might be difficult for anyone who is not grounded in the chanoyu aesthetic to understand how such technical flaws came to be transmuted into beauty marks.

Though it is all but impossible to read, the handwriting does not seem to be Rikyū’s. __________ *Today the nadare seen on modern-made chaire is usually artificially induced, by dripping additional glaze (either the same color or one that will contrast with the other) on the shoulder before firing. Then, when the glaze begins to melt in the kiln, this extra glaze begins to flow over the other, producing a dramatic nadare.

†More literally, “came out” (during firing).

‡They actually appear to be finger marks, the result of the potter’s holding the chaire when it was dipped in the vat of glaze. When the pot was put down to dry, the glaze on the places where the fingers touched it was very thin, so that it started to burn away during firing, resulting in the orange-red blooms.

²⁷Tennōji-ya kaiki [天王寺屋會記] (Sōtatsu ta-kaiki [宗達他會記]):

Tennōji-ya kaiki [天王寺屋會記] is the general name for a collection of five kaiki, written by three successive generations of the Tennōji-ya family*, Tennōji-ya Sōtatsu [天王寺屋 宗達; 1504 ~ 1566], Tennōji-ya Sōkyū [天王寺屋宗及; ? ~ 1591], and Tennōūji-ya Sōbon [天王寺屋宗凡; his dates are unknown†].

Sōtatsu and Sōkyū both wrote two books each -- one that memorializes the details of tea gatherings that they attended as guests (called ta-kaiki [他會記]), and the other (called ji-kaiki [自會記]) that documents gatherings that they hosted for others. Sōbon only authored a ta-kaiki. The books are all styled chanoyu nikki [茶湯日記], which means tea diary.

◦ Sōtatsu chanoyu nikki・ta-kaiki [宗達茶湯日記・他會記], two volumes, covering the years Tenbun 17 [天文十七年] (1548) to Kōji 2 [弘治二年] (1556); and Kōji 3 [弘治三年] (1557) to Eiroku 9 [永祿九年] (1566).

◦ Sōkyū chanoyu nikki・ta-kaiki [宗及茶湯日記・他會記], five volumes, covering the years Eiroku 8 [永祿八年] (1565) to Tenshō 3 [天正三年] (1575); Eiroku 9 [永祿九年] (1566) to Genki 3 [元龜三年] (1572); Tenshō 3 [天正三年] (1575) to Tenshō 6 [天正六年] (1578); Tenshō 7 [天正七年] (1579) to Tenshō 11 [天正十一年] (1583); and, Tenshō 11 [天正十一年] (1583) to Tenshō 13 [天正十三年] (1585).

◦ Sōbon chanoyu nikki・ta-kaiki [宗凡茶湯日記・他會記], two volumes, covering the years Tenshō 18 [天正十八年] (1590), and Genna 1 [元和元年] (1615).

◦ Sōtatsu chanoyu nikki・ji-kaiki [宗達茶湯日記・自會記], two volumes, covering the years Tenbun 17 [天文十七年] (1548) to Kōji 2 [弘治二年] (1556), and Kōji 3 [弘治三] (1557) to Eiroku 9 [永祿九年] (1566).

◦ Sōkyū chanoyu nikki・ji-kaiki [宗及茶湯日記・自會記], six volumes, covering the years Eiroku 9 [永祿九年] (1566) to Tenshō 3 [天正三年] (1575); Tenshō 2 [天正二年] (1574) to Tenshō 4 [天正四年] (1576); Tenshō 4 [天正四年] (1576) to Tenshō 6 [天正六年] (1578); Tenshō 5 [天正五年] (1577) to Tenshō 10 [天正十年] (1582); Tenshō 10 [天正十年] (1582) to Tenshō 15 [天正十五年] (1587); and, Tenshō 11 [天正十一年] (1583) to Tenshō 13 [天正十三年] (1585). ___________ *In interactions with Japanese entities the family used the surname Tsuda [津田].

†This is very curious, considering he was (presumably) Tennōji-ya Sōkyū’s oldest son and heir.

Kogetsu Sōgan [江月宗玩; 1574 ~ 1643], who became the 156th Abbot of the Daitoku-ji, was Sōbon’s younger brother. But since he was born rather late in Sōkyū’s life (Tennōji-ya Sōkyū, though his year of birth is not known, was probably close in age to Rikyū, with whom he had a deep and warm friendship), this gives us no help pinpointing when Sōbon may have been born (meaning it could have been any time between roughly 1540 and 1573).

²��Nitta-katatsuki...no keijō [新田肩衝...の形状], which are Yonehara sensei’s exact words, more literally means “the shape of the Nitta-katatsuki.”

However, the majority of Sōtatsu’s comments, and the quotation in question in particular, are focused on a discussion of the peculiarities of the glaze of this chaire.

²⁹The text actually states, in a parenthetical gloss, tōji zai Kamigata [当時在上方], which means “at that time* (tōji [当時] (the Nitta-katatsuki) was in Kamigata (zai Kamigata [在上方]).” Kamigata [上方] refers to the Ōsaka-Kyōto area.

It can be inferred from what he wrote that Sōtatsu had been summoned to Jōō’s place, across from the Ebisu-dō [惠比壽堂], specifically to inspect the Nitta-katatsuki.

According to the denrai, the Nitta-katatsuki had originally been owned by Shukō, and then by the military commander Miyoshi Masanaga [三好政長; 1508 ~ 1549]†. After him, it was in the possession of Oda Nobunaga, who seems to have given it to Ōtomo Sōrin; with Sōrin, in turn, passing it on to Hideyoshi when Hideyoshi asked him for it‡. ___________ *In other words, at the time when Tennoji-ya Sōtatsu inspected the chaire during a chakai, and wrote this entry in his tea diary.

†He was also known as Miyoshi Sōsan [三好宗三], and was an avid practitioner of chanoyu.

While the denrai implies that this chaire went from Shukō to Miyoshi Sōsan, Shukō died in 1502, while Miyoshi Masanaga was not born until 1503. Therefore the chaire must have passed through at least one other pair of hands in the interum, but this person’s name has not made it into the records.

In the present instance, too, Sōsan died in 1549, Sōtatsu was called to Jōō’s compound to inspect the Nitta-katatsuki in 1550, but the denrai states that the next owner after Sōsan was Oda Nobunaga. Perhaps the chaire remained in the possession of the Miyoshi family following his death, with Sōsan’s heir ultimately deciding to part with it (to, or through, Jōō) in 1550. Precisely when Nobunaga acquired it, or under what circumstances, is not known.

Nevertheless, if it was in Jōō’s keeping, at least temporarily, in 1550, then it certainly was in Kyōto at the time when Sotatsu inspected it.

‡This was a sort of trade. Hideyoshi gave Sōrin a (karamono) nasu-chaire, as well as 100 silver coins, in exchange for the Nitta-katatsuki.

³⁰From the Sōtatsu chanoyu nikki・ta-kaiki (jō) [宗達茶湯日記・他會記・上] (cf. Sadō ko-ten zenshū [茶道古典全集], vol. 7, pages 21 to 22). While I have essentially translated the entire entry below, the passage that is quoted in Yonehara sensei’s essay has been indicated with boldface type.

The entry begins:

The sameᵃ, U-tsukiᵇ, Second day of the Horseᶜ (onaji u-tsuki uma-futatsu [同卯月午貳]).

A message was received from [Jō]ō, [brought by] Takasugi [隆軼] and Sōka [宗珂], togetherᵈ.

○ Katatsuki [カタツキ], Nitta [につた], the bag is kantō (fukuro kantō [袋かんとう]) with the appearance of a grate (samaᵉ kōshi [no] kokoro ari [さまかうし心在]), the tailᶠ is crimson-purple [kurenai no o [くれなヰの尾].

[This is a photo of the original shifuku (or possibly an early Edo period reproduction, if the original was lost in the fire that consumed Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle in 1615, at the conclusion of the war between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori). Note that the colors -- especially the color of the himo (and other red and purple tones) -- will have faded from what they were in the middle of the sixteenth century.]

Sōtatsu then goes on to describe the Nitta-katatsuki in great detail.

一、The shape is like a cylinderᵍ [nari ha tsutsu-giri to aru [なりハつつきりと在]); the neck rises straight up (kubi tachi-nobi sōrō [くひたちのひ候]), so that there is a feeling of unity between the twoʰ (futari to shitaru-kokoro ari nari [ふたりとしたる心有也]); the shoulders are also rounded, without a sharp point [where the body turns into the shoulder], it seems to be [more] gradualⁱ (kata mo kyū ni ha tsukanu nari mukuri to ari yo [かたもきうにハつかぬ也むくりと有歟]).

一、The clay is a whitishʲ, with a smooth surfaceᵏ that nevertheless appears dampˡ (tsuchi, usu-shiroi-yō ni te, sarari to ari, saredo mo, shirui to ari nari [土、うす白きやうにて、さらりと有、されども、しるりと有也]).

一、The glaze (kusuri [藥]): the under-glazeᵐ is blackish, with perhaps a hint of cobalt-blue (ji-gusuri usu-kuroku, ruri-gokoro isasaka-hodo ari yo [地藥うすくろく、るり心いさゝかほと有欤]); there is also a feeling of seaweed-greenⁿ (miru-iro kokoro mo ari nari [みる色心も有也]).

On the surface of the [outer-]glaze, the glaze [has flowed into] two streaks of nadare, which turn toward the left side of the jar (uwa-gusuri men ni aru-tokoro, sono kusuri ni te men [h]e ni suji nadare ari, tsubo no hidari no kata [h]e nejitaru nari [上藥面に在所、其藥にて面へ二筋なたれ在、壺の左の方へねちたる也]). There is a small[er] nadare on the shoulder (kata mijika ni nadare ari [かたみしかになたれ在]).

At the edge of the nadare streaks -- on both streaks -- an orange-red [color] appeared during firingᵒ (nadare no suji no fuchi ni, futa-suji nagara, shu wo yaki-dashi sōrō [なたれのすちのふちに、二筋なから、しゆをやき出候]).

The [outer] glaze stops rather high [on the side of the chaire] (kusuri taka-taka to tomari sōrō [藥たかゝゝととまり候]). Also, even though the glaze is thinner on the sides, there are places where it flowed downwardᵖ (waki [h]e mo kusuri isasaka-hodo-tsutsu sagaritaru tokoro ari nari [わきへも藥いさゝか程つゝさかりたる所有也]). At the edges of the two streaks of nadare, the glaze has a feeling of being a little fuller𐞥 (futa-suji no nadare no saki ni, isasaka-hodo mashiri kusuri no kokoro ari yo [二筋のなたれのさきに、いさゝか程ましり藥の心有欤].

___________ ᵃOnaji [同], “the same,” referring to the year (Tenbun 19 [天文十九年], 1550).

ᵇU-tsuki [卯月], “the month of Deutzia”, in other words, the month when Deutzia (Deutzia crenata) blooms is a poetic name for the Fourth Lunar Month. This name is of great antiquity -- and in the sixteenth century it continued to be used even in cases where the other months are not named in this elegant way (as in this document). This was so that the scribe could avoid writing shi-gatsu [四月] (which sounds like “the month of death”).

ᶜUma-futatsu [午貳] means the second Day of the Horse* (in the Fourth Month). In Tenbun 19 [天文十九年] (1550), this corresponded to the 17th day of the Fourth Month, which was would have been May 3, 1550 (in the proleptic Gregorian calendar). _____ *The days were named according to the usual cycle of the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. The series continued irrespective of the change from one month to the next, so that each animal appeared two or three times each month.

ᵈShū Ō ki-sōrō shimu [從鷗来候使] means a message was brought from Jōō* (perhaps to come and inspect the chaire).

Takasugi・Sōka ryōnin [隆軼・宗珂 兩人]: Takasugi [隆軼] has not been identified; Sōka [宗珂] is possibly Wakasa-ya Sōka [若狹屋宗可; dates unknown], though this should be considered far from proven; ryōnin [兩人] means both of them, implying that the two men conveyed Jōō’s message to Sōtatsu.

Though the details are not clear, it appears that Jōō was summoning Tennōji-ya Sōtatsu to come to inspect the Nitta-katatsuki. Perhaps this was to be done in his compound at Shijō [四条]†; but, as I said, nothing is clear from what Sōtatsu has written.

This gathering, if it can be called that, does not seem to have been a chakai‡. ___________ *Jōō’s [紹鷗] name was commonly abbreviated to Ō [鷗] by his contemporaries.

†The Daikoku-an [大黒庵].

‡There is no indication that anything else was done but inspect the Nitta-katatsuki. Nothing is said about anyone else who may have been present; and no mention is made of refreshments or other amenities.

ᵉSome commentators suggest the first word of this phrase should be shima [しま = 縞], “stripe,” rather than sama [さま], which, in this context, would mean “appearance.”

In the case where the word is shima, the phrase shima kōshi [no] kokoro ari [さまかうし心在] would mean “the stripes give the feeling of a grate.” The word grate implies that the stripes are horizontal (woven with the weft), rather than vertical (set out with the warp), as can be seen in the photo.

Traditionally, most kantō have vertical (warp) stripes.

The original shifuku (or possibly an early Edo period reproduction, as noted above) is shown above.

ᶠKurenai no o [くれなヰの尾]: kuranai [くれない = 紅] is a deep crimson-purple color. O [尾], which literally means tail, is referring to the uchi-dome [打ち留め, 打ち止め] (the part of the himo where the two ends of the cord are braided together into a single length, ending in a little tassel).

Since the kanji that the tea world pronounces himo [緖] can also (and more correctly) be pronounced o, Sōtatsu is either abbreviating or has misunderstood the correct kanji. (The proper kanji for himo is “紐” -- which, for some reason, the tea schools do not like to use.)

ᵍTsutsu-giri [筒切り] is described as being like a length cut from the middle of a daikon (by chopping off the two ends). So it is cylindrical, but also slightly fatter in the middle than at the ends.

ʰIn other words, the way neck rises out of the body of the chaire is pleasing to the eye.

“The two” (futari [ふたり, 二り]) could refer to the lower and upper ends of the neck, or to the feeling of balance between the neck and the shoulder/body of the chaire.

ⁱIn many katatsuki, the line between the shoulder and the body is a sharp ridge. In the case of the Nitta katatsuki, however, the transition from vertical (the side of the body) to horizontal (the surface of the shoulder) is gradual, rounded -- reminiscent of a (cloth) ball or flattened globe.

In the Edo period, this kind of shape came to be described as nadekata [撫で肩], which means “sloping shoulders.”

This sentence concludes with the kanji yo [歟], which indicates that Sōtatsu is framing his remark as a question -- in other words, he is undecided about the exactitude of his description (probably because he only was able to look at the chaire briefly -- during haiken -- and was recording his impressions in his kaiki several hours later).

ʲUsu-shiroi [うす白き] means whitish*. The clay from which the kansaku-karamono were thrown ranged (after firing) from a brownish terracotta color to a light brown or beige. Here it is the latter, albeit pailer or whiter than usual. (Note that the clay became darker after the chaire passed through the fire that burned down Ōsaka castle in 1615.) __________ *Not “light white,” as some have rendered it.

ᵏSarari to ari [さらりと有]: sarari means sleek, smooth. The unglazed clay body of many chaire has a minutely coarse texture (from the fine-grained sand it contains which separates as the clay dries), but that of this chaire is remarkably smooth, as if intentionally rubbed with a fine slip after the pot was thrown.

ˡShiruri [濕り] means damp, moist. The unglazed clay has a slight sheen, as if it were damp.

ᵐJi-gusuri [地藥]: it appears that this chaire was dipped into the glaze vat two times. The first time the glaze was very thin (probably the heavier constituents had settled, leaving a thin, blackish glaze). Perhaps, noticing the problem, the potter dipped it into the vat again (after stirring up the glaze), resulting in a second coating. It was the second coat that produced the nadare.

ⁿMiru-iro [海松色]: miru [海松] is a type of seaweed (Codium fragile, below), the color of which is somewhere between an olive green and a khaki green, as seen on the right.

This is roughly the shade that Sōtatsu is describing here.

ᵒIt is this detail that Yonehara sensei has latched on as proof of the authenticity of Rikyū’s comments that were recorded on the kiri-gata of the Nitta-katatsuki. (Though since anyone with reasonable eyesight would be able to notice this pair of orange-red blushes, it really does not prove any more than that the person who produced the kiri-gata -- whether that was Rikyū or someone else, such as Tsuda Sōkyū -- had first examined the chaire before writing the comments.)

As noted above, this orange-red color developed where the glaze was so thin (because the potter’s fingers had grasped it in those places when it was lowered into the vat of glaze) that it began to burn away during firing.

ᵖPresumably, if the glaze was too thin, even as it melted it would not be able to flow in this way. The most likely reason is that the glaze was rather thin (in other words, the potter had not bothered to stir the glaze before dipping this chaire into the vat), and so the nadare notice on the sides was the result of the liquid glaze flowing before it dried. This, then, had nothing to do with the firing process.

𐞥When the glaze ran as the chaire was being lifted out of the vat of glaze, at some point it lost the ability to continue flowing (a result of the amount of water remaining versus the dryness of the clay), so a little glaze continued to flow on top of the other before it dried completely, making the edges seem slightly thicker. This can be easily seen in the photo (under footnote 25), where the edges of the nadare appear slightly darker than the glaze immediately above them. This effect could also have been the result of the first coat of very thin (albeit blackish) glaze dissolving off the surface of the pot as it was dipped into the vat, and being carried to the edges as the second glaze ran over the surface.

Pots like the katatsuki chaire were usually dipped into the vat of glaze with the mouth facing downward (because the intention was to glaze the outside, not the inside*), and then turned over with the wrist (so the mouth was facing upward) before putting them down on a board to dry. The nadare developed on the side that had been held lowest as the chaire was being turned over (since the glaze would have flowed toward that side when wet, with the result that the layer of glaze would have been slightly thicker on that side of the pot). Care was taken to keep glaze off of the foot (otherwise the chaire would stick to the other pieces when the glaze melted). The actual flowing of the glaze during firing seems to have been minimal in the case of this particular chaire. __________ *These jars were originally made to contain powdered medicinal herbs. Glazing the outside while leaving the foot and inside unglazed would allow atmospheric moisture to pass through the clay, so that the medicinal herbs did not become too dry.

It is only in relatively recent times that chaire were intentionally glazed on the inside (to help prevent the matcha from sticking to the inside, making the chaire difficult to clean completely) -- and this is one way to tell if the chaire was really made several hundred years ago nor not.

³¹Tennōji-ya to Ōtomo-shi to no kōryū no shinmitsu sa mo kangaete yoi [天王寺屋と大友氏との交流の親密さも考えてよい].

Yoneyama sensei appears to be arguing that, because of the intimate relationship between the Tennoji-ya house and the Otomo clan, it seems easier to believe that Sōtatsu, or perhaps his son Sōkyū, would have been able to trade on this intimacy to gain access to this treasured chaire for long enough not only to inspect it carefully, but also cut the silhouette (which would have had to be done with the chaire physically in front of the cutter)*. And this connection would also explain the near-identical wording between Sōtatsu’s tea diary entry and the kaki-ire inscribed on the Nitta-katatsuki kiri-gata†.

The same cannot be said if the cutter is supposed to have been Rikyū, since nothing that is known might suggest that he was similarly placed vis-à-vis the Ōtomo family in 1559 -- especially if we also remember the logistical problem of his needing to travel from Sakai to Bungo in the little time available between the conclusion of his chakai in Sakai on the morning of the 23rd day of the Fourth Month, and his cutting of the kiri-gata on the first day of the Fifth Month -- which would have required his gaining access to the chaire immediately upon his arrival at Ōtomo Sōrin’s Fuchū-jō. ___________ *Then, too, there is the matter of Ko-getsu Sōgan’s association with the Ryūkō-in [龍光院] (following the almost immediate death of Shun-oku Sōen, the actual founder of that sub-temple, after he took up residence there). This connection would explain why these chaire kiri-gata came to be preserved there (if we assume they were made by either Ko-getsu’s grandfather Sōtatsu, or his father Sōkyū) -- while a connection between Rikyū and this temple could not have existed, since it was not erected until more than a decade after Rikyū’s seppuku (and the tea connection was to Kuroda Nagamasa, Tennōji-ya Sōkyū, Kobori Masakazu, and the Sakai, Chikuzen, and Hakata merchants of the early Edo period).

†Sōkyū, as Sōtatsu’s son, would have had access to his father’s papers, and was inspired by them to create his own series of tea diaries.

³²Sunawachi shigeki ga ōku, Rikyū mo chaire kiri-gata wo sakusei-shita de arou [すなわち刺激が多く、利休も茶入切型を作成したであろう].

Yonehara sensei is here arguing that, while the chaire kiri-gata that we are considering in this appendix may have been made by someone else (such as Tennōji-ya Sōtatsu or his son Sōkyū), it is also likely, given the environment in which he was living, that Rikyū, too, produced some (unknown) kiri-gata of his own during these years*. The problem is that if any such were the case, there is simply no evidence to suggest that he actually did so†. __________ *It must be mentioned that Yonehara sensei was commissioned to write a biography of Rikyū for the Rikyū daijiten [利休大事典] (which was scheduled to be published just in advance of the 400th anniversary of Rikyū’s death in 1992). And the curious lack of a notable surviving record from that period suggests that in the decade or so following the death of Jōō, Rikyū was living under a cloud, with little participation in the tea life of his community. The fact of the matter is that if Yonehara sensei did not bring up these purported Rikyū chaire kiri-gata, he would have had nothing at all to say about Rikyū between the ages of 37 and 43 -- the very time when he would presumably have been building up his store of fiscal and intellectual resources that would ultimately propel him into a public life that brought him close to the highest power brokers in the land.

†As I mentioned earlier in the footnotes, it really does not seem to be in character that Rikyū would have made tools like this. One of the points of gokushin training was that the chajin should train his eye and develop his muscle memory so that the whole concept of kane-wari became ingrained into his subconscious. The chaire kiri-gata, on the other hand, suggest someone who lacks a true understanding of kane-wari trying to make sense of the matter of why these specific chaire were considered meibutsu -- where, according to the original definition, meibutsu implied a utensil that, in the context of kane-wari, either defined a new temae or so perfectly fit into the temae defined by some other utensil that it could be used interchangeably. If this “rule” was not understood, then the question of why the size of the utensils (measured down to fractions of a bu [分]) would be mystifying -- both then, and in the present day.

³³Can we really justify considering a decade “not so many years*?” Rikyū first made Chōjirō’s acquaintance during the time when he was sculpting the finials and other ornamental figures that would grace the roofs of Hideyoshi’s monumental Juraku-dai [聚樂第] palace†, circa 1586‡.

Far from creating something new (as the effort is often portrayed), Rikyū’s original desire was for Chōjirō to produce a reproduction of the honey-brown Seto-chawan that Rikyū had received (as a sort of parting gift or consolation prize**) from Kitamuki Dōchin at the time when his collapsed finances no longer permitted him to continue receiving Dōchin's instructions††. __________ *Yagate [やがて] literally means soon, presently, before long, in a short time -- so even my translation of “not so many years” is a stretch that, one might argue, goes beyond Yonehara sensei's language.

(Many chajin appear to believe that Chōjirō began to produce chawan for Rikyū even as early as the 1570s, despite there being no actual evidence to support such a belief. The same kind of idea regarding the earlier origins of the small room is pervasive, even though the evidence all points to the spring or early summer of 1555 as the most likely starting date.)

†The purpose of the “Raku” [樂] seal was to distinguish these works as having been produced specifically (and exclusively) for Hideyoshi’s building project -- and so discourage theft. The seal was not used to indicate the name of the potter, and never was considered in that light at the time.

‡Construction began in 1586, though it is unclear how long before that date the production of the roof tiles actually commenced. Be that as it may, even though he was a member of the expatriate community in Sakai, Rikyū does not seem to have known Chōjirō before he became involved in Hideyoshi’s project.

**Unfortunately, when Rikyū’s house was forced into bankruptcy by their creditors, Dōchin immediately brought an end to the lessons, since Rikyū no longer held any interest for him. Still, in light of the money and gifts that Rikyū had given to Dōchin over the years, Dōchin was obligated to give Rikyū some sort of parting gift (and this Seto chawan is shown below, on the left).

However, by the nature of this chawan, Dōchin was clearly telling Rikyū that he should give up any pretense at practicing gokushin tea; and, rather, focus his future tea activities on wabi-no-chanoyu.

His decision to introduce Rikyū to Jōō was also a kindness, and one that allowed Dōchin to extricate himself from Jōō’s apparently incessant questions about the secret details of gokushin-no-chanoyu and kane-wari (since Rikyū would be able to barter his knowledge to ingratiate himself with the master), as well as allow Rikyū to offload his collection of Chinese utensils on the most favorable terms possible. (Jōō’s gifts to Rikyū at the conclusion of their deal aligned with Dōchin’s recommendation, while also filling in the gaps in Rikyū’s new collection of emphatically wabi utensils: for example, while Dōchin gave Rikyū a small chawan, Joo added the large chawan that would allow Rikyū to use the smaller one as his kae-chawan, in accordance with gokushin practice.)

††Dōchin’s chawan (on the left, alongside one of Chōjirō’s first red chawan) had been selected according to the teachings of kane-wari, making it valuable to anyone who understood (or wished to understand) those teachings. For this reason, Rikyū was able to sell it shortly after receiving it, to raise money to sustain his family.

³⁴Ima-yaki [今燒] means “fired in the present.” This is how Chōjirō’s early chawan were styled in the tea documents that survive from the 1580s. They were sometimes also known as Rikyū-yaki [利休燒], indicating that it was common knowledge that these bowls were being made under Rikyū’s direct influence. The term Raku-yaki [樂燒] does not seem to have been used before the Edo period.

When Rikyū referred to these bowls, he usually did so by the names that he had given them (such as O-guro [小グロ, オグロ]/Ō-guro [大グロ, オーグロ]* and Ko-mamori [木守, コマモリ]); or, alternatively, simply as kuro-chawan [黒茶碗]† or aka-chawan [赤茶碗]. __________ *Rikyū seems to have preferred using these two black bowls together, since the fact that the one was a little larger than the other meant that they could be stacked together (with a dry chakin in between, to keep them from sticking together). When he did so, he wrote just a single, ambiguously rendered, name as “オ・グロ” which could be interpreted as either O-guro or Ō-guro (and so naming both of them at once).

†This can be confusing, since he also calls other contemporaneous black-glazed bowls kuro-chawan, such as those produced at the Seto kiln by Furuta Sōshitsu.

³⁵This gloss is formatted as such in Yonehara sensei's text.

While a paper kiri-gata may have sufficed for the early Raku bowls (since the original model, the honey-brown Seto chawan shown under footnote 32, has a fairly regular shape), some scholars argue that Rikyū’s models for Chōjirō were more likely made from a sort of papier-mâché, made by soaking waste paper in water for some time -- since the three-dimensional qualities of these later chawan could never be suggested by a two-dimensional silhouette (which is useful only when attempting to represent highly symmetrical objects -- such as the classical chaire).

³⁶Yoshida Kanemi [吉田兼見; 1535 ~ 1610] was a Shintō shrine official who lived from the Sengoku to the early Edo period. He was born in 1583, as the eldest son of Yoshida Kaneyoshi. He served at the Yoshida Shrine (Yoshida jinja [吉田神社] in Kyōto. In 1586, after receiving permission to rebuild the Jingikan [神祇官] (the Shrine’s administrative office) of the Hasshin-den [八神殿] (all of which existed within the confines of the Yoshida Shrine), his family assumed the duty of officiating at the rituals (saishi [祭祀]) in that shrine. He also appears to have been an avid practitioner of chanoyu.

Kanemi died on the second day of the Ninth Month of Keichō 15 [慶長15年] (1612).

³⁷Tōyō-bō [東陽坊] is referring to the monk Tōyō-bō Chōsei [東陽坊長盛; 1515 ~ 1598]. He was a disciple of Rikyū’s -- from whom he received the black Raku-chawan that is eponymously known as Tōyō-bō*.

Chōsei lived as the resident monk in the Tōyō-bō, a small hall on the grounds of the Shin-nyō-dō [眞如堂], a Tendai temple (the principal image is of Amida Buddha [阿彌陀佛]) northeast of the Heian Shrine in Kyōto, where Chōsei is also buried.

Chōsei participated in the Kitano Grand Tea Gathering (Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶ノ會]), in the autumn of 1587; and the room he erected at Kitano was later relocated to the grounds of the Kennin-ji, where it remains to this day. This ni-jō daime chashitsu is accordingly known as Tōyō-bō†. ___________ *Though considered by many to be the original, this bowl appears to have been a copy made during the early Edo period (perhaps at the time when the original was damaged or broken).

Scholars also suggest that this is likewise the case for most of the chawan purportedly made by the first three generations of the Raku family.

†This Tōyō-bō chashitsu was modelled on Rikyū’s 1555 tea room, the Jissō-an [實相庵], with the details of the windows that give light to the utensil mat perhaps borrowed from Nambō Sōkei’s Shū-un-an [集雲庵].

³⁸Tenshō ju-go nen (1587) ku-gatsu Yoshida Kanemi ga Tōyō-bō ni annai-sare, San-jō kama-za de Rikyū kiri-gata no kama wo motomete-iru rei mo kono-sai sōki-shite okō [天正十五年 (1587) 九月吉田兼見が東陽坊に案内され、三条釜座で利休切型の釜を求めている例もこの際想起しておこう].

Yonehara sensei’s argument seems to be that the existence of the story of this episode can be taken as a kind of proof that Rikyū created kiri-gata -- even if the kiri-gata in question was of a kama, rather than a chaire or chawan. That said, it would be rather curious that Rikyū would have created a kiri-gata of his own kama (or a kama that he designed) -- unless Yonehara sensei means that this was the kiri-gata that Rikyū provided to the kama-shi when ordering the kama.

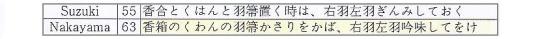

Traditionally, the craftsmen preserved the official shapes of the various named utensils as wooden kiri-gata (which represented the negative of the silhouette), such as that shown above (this one depicts the kiri-gata for the Tōyōbō-kama [東陽坊釜]). It is possible that Yoshida Kanemi was searching for the kiri-gata of the Tōyōbō-kama on the described occasion* (the authenticity of which he may have wished the Tōyō-bō to confirm). ___________ *Otherwise why involve Tōyō-bō Chōsei at all?

The most likely reason for all this trouble was that Kanemi wished to order a copy of the Tōyōbō-kama, and wanted Chōsei to confirm that it was correct before going to the expense of having one cast. Though such a story would be more at home in the Edo period than in 1587.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

❖ As the international exchange rate continues to collapse, your help is even more necessary than heretofore, since this blog is my only source of income. Please donate, if you can.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Appendix: the Rikyū Chaire Kiri-gata [利休茶入切型], Part 1.

The Rikyū chaire kiri-gata is a collection of cut-paper silhouettes¹ of a number of the famous chaire of Rikyū’s day, perhaps a byproduct of his reflections on Jōō and his teachings². This collection of kiri-gata are preserved in the Daitoku-ji, but they are rarely exhibited, and so are not widely known.

In a blog post devoted to this collection of chaire kiri-gata, Kawabe Rieko [川邊りえこ; her date of birth cannot be verified at this time] wrote that [the word] kiri-gata [切型] [generally refers to] silhouettes used to order utensils from artisans³.

[But] these [chaire kiri-gata] are kept secret⁴. Rikyū crafted them himself to memorialize the shapes (and other details) of the famous chaire that he saw at gatherings and on other occasions⁵. They were handmade and inscribed between the First Year of Eiroku 1 [永祿元年] (1558) and Eiroku 7 [永祿七年] (1564), when Rikyū was between 37 and 46 years of age⁶.

The kiri-gata were cut from a variety of different kinds of scrap paper, including the paper used as kaishi [懷紙]⁷.

The shapes of the famous chaire of his period, such as Hatsu-hana [初花], nasu [茄子], and the Uesugi hyōtan [上杉瓢簞] have been preserved among these paper kiri-gata. Rikyū’s careful recording of specific details, where these were critical to the identification of a specific chaire, is a testimony to Rikyū’s deep dedication to chanoyu. [...]

❦ ❦ ❦

Detailed descriptions of the chaire kiri-gata are few and far between⁸. The most commonly referenced discussion is found in an essay by the Japanese scholar and historian Yonehara Masayoshi [米原正義; 1923 ~ 2011] in the Rikyū Daijiten [利休大事典]⁹. This essay was included in the chapter Rikyū and the Ruler (Rikyū to tenka-bito [利休と天下人]), in the subsection entitled Rikyū chaire kiri-gata [利休茶入切型]. Translating from that source:

During the Eiroku [永祿] era¹⁰, Rikyū entered his forties. During that period he was motivated¹¹ to embark on a study of the meibutsu-chaire -- observing them with his own eyes wherever they were to be found, cutting paper silhouettes [of each], and writing down a careful record of his observations as part of his learning process. This can all be understood from the roughly 50 chaire kiri-gata of Rikyū that are preserved in the Ryūkō-in [龍光院]¹² sub-temple of the Daitoku-ji. It is believed that these chaire kiri-gata were created between 1558 and 1567, when Rikyū would have been 37 to 43 years of age.

The earliest known photographs [of some of these chaire kiri-gata] were published in 1931, in the second volume (part 2) of the Sakai-shi shi [堺市史] (Sakai City History)¹³, under the title Rikyū ji-saku chaire kiri-gata [利休自作茶入切形]. The next mention is in the 1935-published Sadō zen-shu [茶道全集], volume 9, where Nakamura Kiyozō [中村喜代三; his dates cannot be confirmed] contributed an essay entitled Rikyū ji-saku chaire kiri-gata [利休自作の茶入切型] that included detailed descriptions of 24 of the chaire¹⁴.

Recent scholarship appears to confirm that these chaire kiri-gata were cut by Rikyū with a degree of certainty, although the basis for this argument rests on a written statement to that effect that is found on the paper wrapper [in which the kiri-gata are kept]. This certification reads:

yotsu no nasubi katatsuki mata ko-tsubo tomo kata natsume ni ka kata

nani mo Sōeki kirare-sōrō nari

[四ツノナスビ カタツキ又小壺共かた ナツメ二ヶかた

何も宗易切られ候也]¹⁵.

However, since the Ryūkō-in was [effectively -- see footnote 12] established by Tsuda Sōkyū’s son Ko-getsu Sōgan [江月宗玩; 1574 ~ 1643], many scholars consider that the most logical way to understand the matter is that the kiri-gata were created by [Ko-getsu’s] father Sōkyū (for example, the argument laid out in the second volume of Nagashima Fukutarō’s Sadō-bunka ron-shū [茶道文化論集]¹⁶).

Now, [with respect to the words] nani mo Sōeki kirare-sōrō nari [何も宗易切られ候也] -- “all were cut by Sōeki” -- let us look at kiri-gata that depicts the Nitta-katatsuki [新田肩衝]¹⁷, which is among the ones [kept in that wrapper].

[I have no idea why a photograph of this kiri-gata was not included in Yonehara Masayoshi’s essay¹⁸. The editors included the two large color photos reproduced above, but the Nitta-katatsuki is not to be found among the 32 kiri-gata arranged in those photos. At any rate, this is the kiri-gata that Yonehara sensei is discussing here -- taken from the chapter in volume 9 of the Sadō zen-shū ( 茶道全集 巻の九 ), page 364.]

[The block of text on the right side of] this kiri-kata reads, “on the first day of the Fifth Month of the Second Year of Eiroku, ki-bi, in Bungo, [I] examined [this chaire]¹⁹.” If we accept that Rikyū [was the man responsible for] cutting this kiri-gata on the first day of the Fifth Month of Eiroku 2 [1559], then he must have examined the Nitta-katatsuki in Ōtomo Sōrin’s Fuchū castle [府中城] in Bungo [since that is where the katatsuki was being kept at that time]. However, since (according to the Hisamasa cha kai-ki [久政茶会記]²⁰) Rikyū hosted a tea gathering in Sakai on the morning of the 23rd day of the Fourth Month, this raises the problem [of logistics²¹].

For Sōrin and the Bungo Ōtomo clan [豊後大友氏], moreover, Eiroku 2 was a truly momentous year: in the Sixth Month he was appointed shugo [守護; military governor] of the six provinces; and in the Eleventh Month, [Sōrin] was elevated to Kyūshū tandai [九���探題; in effect, the governor of Kyūshū]. Moreover, [Ōtomo Sōrin] also succeeded to the role of katoku [家督], the headship of the Ouchi clan [大内氏]²², and from this time onward his power was in the ascendant.

Furthermore, in a letter addressed to Ōtomo Yoshishige [Sōrin] dated the 20th of the Eleventh Month [of the same year, Eiroku 2], [the nobleman] Koga Sōnyū [久我宗入; 1519 ~ 1575] ([known more formally as] Harumichi [晴通])²³ wrote: “since [I] have a desire to see [your] chanoyu, I will definitely go down [to Bungo, to visit you]²⁴.” The kuge-shū [公家衆; court nobles] in Kyōto were clearly well aware of Ōtomo Yoshishige’s attachment to chanoyu, and this had given rise to his reputation for owning meibutsu utensils. There is no reason to doubt that the Nitta-katatsuki was certainly in Ōtomo Yoshishige’s hands [at this time], so the surrounding context of this episode leaves us with nothing to question²⁵.

[Yonehara sensei’s essay will continue in the next post.]

_________________________

¹The word kiri-gata [切型], most of the well-known examples of which were produced during the Edo period, usually referred to silhouettes cut from paper that were used to order chaire from potters in China -- either as replacements* for famous chaire that had been presented to the daimyō early in the Edo period (as rewards for their assistance in the wars against Toyotomi Hideyori and Ishida Mitsunari: when the government started to run out of money and fiefs that they could grant to the daimyō for their military support, they turned to the only resource that had survived the wars -- Hideyoshi’s collection of meibutsu tea utensils).

The kiri-gata in this set, however, were created by Rikyū for his own use, as a way to preserve the details of the famous chaire that he had been able to inspect closely over the years for his own reference. __________ *When, for example, the chaire had been broken -- sometimes accidentally, but on at least several occasions this was done on purpose (so that the daimyō in question could “share” the government's bounty with his own retainers by offering each a shard, as he would have done had the donation come in the form of money or a grant of land).

While originally these chaire had been gifts that would belong to the daimyō and his family in perpetuity (which was why some of the daimyō, seriously offended by this poor reward for their services, treated them so cavalierly), eventually the bakufu, finding that their supply of tea utensils was running low, changed the policy by declaring that the gift was only for the lifetime of its recipient -- after which the chaire had to be returned. It was in the rush to replace pieces that had been broken that the idea of ordering directly from Chinese potters had begun (since trade relations with the continent had been normalized during the early Edo period) after this new policy was announced; and later the idea was expanded as a sort of insurance policy (often with numerous identical examples being ordered at the same time) to protect the family against the possibility of their chaire being broken or lost at some future date. (This also fueled the establishment of special fabric mills in both Kyōto and Edo that specialized in the reproduction of high-quality copies of the meibutsu-gire [名物裂] that had been used to make the original shifuku of the famous chaire -- since this would enhance the feeling of authenticity of the fake chaire.)

Some of these “sets” of identical chaire copies are still known to exist, though in the present climate they are rarely displayed together (since that would cast doubt on the authenticity of the one that is supposed to be the original).

²The whole idea of kiri-gata [切型] seems closer to Jōō’s early approach to chanoyu than to Rikyū’s*. This suggests that either Rikyū was carrying on a tradition that was initiated by Jōō, or that the urge to produce these kiri-gata was inspired by his reflection on Jōō and his approach to chanoyu.

Many of the chaire included in this selection had passed through Jōō’s hands at one time or another during his career as an antique dealer, and that may have been where Rikyū first saw them (or at least learned about their importance to the preservation of these important details).

The reflection on, and attempts to preserve, Jōō’s teachings seems to have been a common motivation shared by his principal disciples. In addition to Rikyū, during the same time frame the daimyō Uesugi Kenshin [上杉謙信; 1530 ~ 1578] set about writing down (and commenting upon) the secret teachings imparted to him by Jōō, which collection of three scrolls is today known as the Chanoyu san-byak’ka jō [茶湯三百箇條]; while Nambō Sōkei spent this time pondering the series of kiri-kami [切紙]† that set out the evolution of the tea of the daisu which Jōō had bequeathed him from his deathbed -- the collection of documents that ultimately came to be preserved as Book Five of the Nampō roku. ___________ *Jōō, as has been mentioned many times before, was originally an antique dealer. This, coupled with his continued pestering of Kitamuki Dōchin over the details of the gokushin-temae (in which the rules of kane-wari play a decisively fundamental part), suggests that Jōō -- like the chajin of the Edo period and after -- was intrigued, yet mystified, regarding the reason for the specific sizes of the various utensils that were used for chanoyu. And so, rather than simply accepting them and then moving on, he would have fixated on this detail, making things like the fabricating kiri-gata a valuable exercise that would help visualize the utensils, and so inform the way that those utensils combined together during the service of tea.

†Kiri-kami [切紙], in this context, refers to a collection of unbound, individual leaves of paper -- in this particular case, with one arrangement illustrated on each sheet.

In 1573 Nambō Sōkei took this collection of papers to Rikyū, and asked him for an explanation of them. This is how the numerous kaki-ire [書入] that appear throughout Book Five of the Nampo roku came to be there.

³However, this was not their purpose in the present context. Rikyū created these chaire kiri-gata as a way to memorialize the details -- including the shape and size -- of the meibutsu pieces of his day for his own reference.

The first part of this appendix is based on the blog-post entitled Rikyū chaire kiri-gata [利休茶入切型], from Kawabe Eriko sensei’s blog Kawabe Eriko no Tsure-zure-gusa [川邊りえこの徒然草].

The URL for Kawabe sensei’s post is:

http://miyabigoto.com/blog/2010/04/post-255.html

I have generally translated her remarks rather freely, so they will be part of the narrative that I wish to delineate here. (Kawabe sensei, on the other hand, was describing a special exhibition when she was able to inspect some of the chaire kiri-gata along side the chaire that they represented, so her remarks are focused on that situation. Her account is the only one that I was able to find online, and that is why I decided to lead with it in this post.)

⁴This statement seems to be referring specifically to the Rikyū chaire kiri-gata, with their being kept “secret” perhaps because they disclose not only the shapes and peculiarities of the glazes of the various chaire, but also the minute details of their dimensions*.

It is an unfortunate fact of history that, when the Japanese tea schools† do not understand something, or do not understand the purpose for something or why something is so, they inevitably declare it to be “secret.” This, coupled with their penchant to quote “authorities” without ever bothering to fact-check them (so that a certain statement might be repeated for literal centuries -- yet when one actually goes back to the purported original source, it is found that it either never existed, or has been conveniently “lost” without any trace, usually long before the teaching that is ascribed to it ever began circulating), is why Japanese scholarship (on chanoyu and the other cultural / traditional arts organizations controlled by similar iemoto-style systems, at least) is fraught and, frankly, almost impossible for an “outsider” to crack‡. ___________ *The sizes relate directly to the teaching of kane-wari. While this may have been the reason why they were considered “secret,” the more likely explanation is that, once the theory of kane-wari was forgotten (over the course of the several decades after Rikyū’s death, when the practice of chanoyu went into a sort of forced hibernation), the reason why such details were significant was no longer known. So, lacking this reason, they were declared “secret” to actively discourage further questioning.

†There is no such thing as an independent scholar working in the field of chanoyu studies. Everyone is affiliated with one or another of the modern schools -- and it is a prerequisite of their work that it must reflect the views of the school with which he or she is connected.

As one Japanese scholar said to me, “to attempt to pursue such research without any affiliation would be tantamount to professional suicide.”

‡While the “insiders” content themselves with mindlessly repeating what they were told.

A small, and very trivial example of this: several decades ago a certain authority said, during a presentation in a Western country, that Rikyū’s favorite color was dark blue, and that he always wore a dark blue kimono when serving tea.

Yet if we actually go back to the records from his time, we have to conclude that his favorite colors were dark blood-red and black; and, when serving tea Rikyū invariably wore a kami-ko [紙子] (a kimono made from heavy, specially processed paper) that had been dyed with shibu [澁] (persimmon juice, which makes the paper slightly impervious to water), so it would have been brick-red, over which he wore a black jittoku [十德], with a black-dyed cotton zukin [頭巾] on his head -- as imagined in the picture, above (which I modified to reflect the description in period documents). Yet in no modern books is Rikyū ever said to be dressed in this way (though the blue-garbed anecdote continues to manifest itself in prose -- and cinematic -- depictions to this day).

‡This was not difficult because it appears that Rikyū’s influence had remained primarily within a small circle of Hideyoshi’s closest advisors and confidants, while the fact that Imai Sōkyū retained control of Jōō’s collection of meibutsu utensils (and so his legacy as a teacher) meant that the tea world, in general, looked to him for guidance -- and, following his death, to Oribe.

⁵In addition to their use during tea gatherings, it was not uncommon for famous pieces to be displayed in the reception rooms of the wealthy, usually arranged in situ, even when they were not actually being used to serve tea.

⁶During this period Rikyū was still under a cloud -- the blame for the drastic changes that had been made during Jōō’s final months (following, and inspired by, Rikyū’s return from the continent) having been rained down on him following the master’s death -- and appears to have largely kept himself out of the public eye when that could be avoided. This is probably why the only reference to Rikyū’s activity during this period that Yonehara sensei could uncover was these chaire kiri-gata.

It may have been for this reason -- to amuse himself during his self-imposed semi-retirement -- that he began working on this collection of kiri-gata.

⁷Paper was a precious commodity, and the people of that day did not ruin a perfectly good sheet of paper for purposes such as this. However, there were always random bits of paper, cut from the ends of letters, and so forth, and this paper would be put to use on projects such as this*.

While kaishi originally referred to a packet of note-paper that people kept in the futokoro (so they had something to write on if the occasion demanded it), here the reference is to the smaller kind of kaishi (Rikyū’s kaishi was the size of modern women’s kaishi, though the paper was much thinner than what is seen today) that is used during the tea gathering when handling the footwear and eating the kashi.

The use of this kind of paper suggests that those particular kiri-gata may have been made during chakai that Rikyū attended, when the chaire was directly in front of him. ___________ *Love letters were traditionally written on just these kinds of odd scraps -- the use of which was supposed to imply that the author had been so overcome by passion, or other emotion, that he or she could not wait long enough to provide themself with a properly cut piece of writing paper.

As has been mentioned before in this blog, there was an entire industry that grew up around the recycling of waste paper -- and, indeed, it was for just this reason that Nambō Sōkei, charged (in his unofficial capacity as Rikyū’s steward of the Sakai household) with disposing of Rikyū’s old archives -- as the household was preparing to remove to the newly constructed compound at Mozuno. Thus Sōkei was able to peruse, and so rescue, many of the documents that eventually made their way into the Rikyū chanoyu sho [利休茶湯書] and the Nampō roku [南方錄].

⁸Unfortunately, the only photos available (which are the two reproduced above) are not clear enough for me to be able to read the writing, even when enlarged.

⁹利休大事典, 淡交社, 1989・10; ISBN4-473-01110-0.

Yonehara sensei’s essay Rikyū chaire kiri-gata [利休茶入切型] is found on pages 46 to 48.

¹⁰1558 ~ 1570.

¹¹Hagemi [励み] means encouragement, incentive, motivator, inducement.

However, Yonehara sensei does not give us any clue as to what he believes motivated Rikyū's (apparently) sudden interest in undertaking this kind of study.

My personal feeling (as I suggested above) is that his efforts were inspired by reflecting on Jōō and his legacy. While Rikyū had studied gokushin-no-chanoyu under Kitamuki Dōchin, which would have informed him why the measurements of the various utensils were important, it was from Jōō that Rikyū learned about the utensils themselves (as an antique dealer, Jōō had vast hands-on experience with them -- especially since most of them had been in his hands at one time or another -- whereas Dōchin's rather modest means meant that he was principally teaching his disciples theoretically, with probably little more than a single set of utensils with which they could practice the temae in his presence).

¹²The Ryūkō-in [龍光院] is technically a tat’chū [塔頭], which is a sort of mortuary or memorial temple -- in this case, the Ryūkō-in was erected by Kuroda Nagamasa [黒田長政; 1568 ~ 1623]* in 1606, as a memorial to his father, Kuroda Yoshitaka [黒田孝高; 1546 ~ 1604]. The name of the temple, Ryūkō-in, comes from Yoshitaka’s posthumous Buddhist name, Ryōkōinden-josui-ensei dai-kōji [龍光院殿如水圓淸大居士].

This sub-temple was founded under the auspices of Shun-oku Sōen [春屋宗園; 1529 ~ 1611], the 111th abbot of the Daitoku-ji, who retired to the Ryūkō-in during the winter of 1610~11, dying shortly thereafter. Because Shun-oku Sōen was resident in the Ryūkō-in only briefly, however, it is often considered that Ko-getsu Sōgan [江月宗玩; 1574 ~ 1643], the 156th Abbot of the Daitoku-ji, to have been its de facto founder.

The Ryūkō-in preserves a large collection of tea utensils, the core of which were pieces donated by Nagamasa from the Kuroda family’s collection -- though this was greatly expanded by gifts from various Sakai merchant-chajin and, through Ko-getsu Sōgan, much of the collection of Tennōji-ya (Tsuda) Sōkyū†. __________ *One of his retainers was Tachibana Jitsuzan, and it was Nagamasa who gave Jitsuzan permission to make an excursion to the Nanshū-ji during their journey to Edo; while it was at his request that Jitsuzan was given permission to unseal the Shū-un-an and peruse the collection of documents housed in Nambō Sōkei’s wooden chest.

†Ko-getsu Sōgan was the son of Tennōji-ya (Tsuda) Sōkyū.

¹³Sakai-shi shi, dai-ni-kan, honpen dai-ni [堺市史 第二巻・本篇第二].

There is some confusion regarding this document, since Yonehara sensei states that this document dates from Shōwa 6 [昭和六年] (1931). Unfortunately, this document appears to have been lost, since the Sakai-shi shi in the Sakai City Library (as well the earliest edition held in the National Diet Libraries) only goes back to Volume 3 (Sakai-shi shi, dai-san-kan, honpen dai-san [堺市史 第三巻・本編第三]). Volume 3, furthermore, is dated 1930 in the catalog.

Be that as it may, since Volume 2 is unavailable, it is not possible to check this reference to see which Rikyū chaire kiri-gata were photographed for preservation there.

¹⁴Sadō zen-shu, maki no ku [茶道全集 巻の九], pages 361 to 404.

The details of the 24 chaire kiri-gata are discussed in this section by the Urasenke-affiliated scholar Nakamura Kiyozō [中村喜代三; his dates cannot be confirmed]. This material will be translated in the next post.

¹⁵Yotsu no nasubi, katatsuki mata ko-tsubo tomo kata, natsume ni ka kata, nani mo Sōeki kirare-sōrō nari [四ツノナスビ、カタツキ又小壺共かた、ナツメ二ヶかた、何も宗易切られ候也].

Yotsu no nasubi [四ツノナスビ] means “four nasubi” (that is, four nasu-chaire [茄子茶入]). The kanji-compound “茄子” can be read nasubi as well as nasu.

Katatsuki mata ko-tsubo tomo kata [カタツキ又小壺共かた] means “katatsuki, and also ko-tsubo, of the same sort*.”

Nani mo Sōeki kirare-sōrō nari [何も宗易切られ候也] means “all of which were cut by Sōeki (in other words, Rikyū).”

The last sentence could be taken to mean that this identification written on the wrapper might have been written by someone other than Rikyū†. __________ *Meaning they were paper silhouettes like the others.

†Though we occasionally find references to oneself phrased in the third person in documents from that period. So this cannot be taken as definitive.

¹⁶Sadō-bunka ronshū, ge-kan [茶道文化論集・下巻]: Collected Essays on Tea Ceremony Culture in English.

Nagashima Fukutaro [永島福太郎; 1912 ~ 2008] was another Urasenke-affiliated scholar, with his several books all being published by Tankōsha.

¹⁷Nitta-katatsuki [新田肩衝].

In the Taishō mei-ki kan [大正名器鑑], Takahashi Yoshio [高橋 義雄; 1861 ~ 1937] (also known as Takahashi Sōan [高橋箒庵]) describes this chaire in this way:

Ō-meibutsu [大名物]ᵃ. Kansaku-karamono [漢作唐物]ᵇ. Katatsuki [肩衝].

[Illustrations from the Taishō mei-ki kan showing the front of the Nitta-katatsuki, the bottom, and the lid of its hikiya (挽家).]

The name Nitta [新田] is thought to be the name of a person, but [this person] has not been identified.

Height: 2-sun 8-bu [二寸八分] (8.5 cmᶜ); diameter of the body: slightly over 2-sun 5-bu [二寸五分強]ᵈ (7.7 cm); circumference of the body: 8-sun 1-bu [八寸一分] (24.5 cm); diameter of the mouth: 1-sun 5-bu [一寸五分] (4.5 cm); height of the koshiki [甑]ᵉ: slightly over 5-bu [五分強] (1.4cm); width of the shoulders: 3-bu 5-riᶠ [三分五厘] (1.0 cm); weight: 32 monmeᵍ [三二匁] (120.0 g).

The koshiki [甑] is slightly elongated, with a single ridge running along the neck’s inner surface; the mouth flares, the shoulders are slightly rounded and sloping, and the body is quite bulbous. Furthermore, while this type [of chaire] often has a flat base [resulting from its being cut from the potter’s wheel with a bamboo spatula], this one has a base that was cut with a string, resulting in a concentric swirl forming a concavity. Overall, [the chaire] is a yellowish-gray-brown color with a glossy finishʰ. The glaze on oki-gata [置形]ʲ has flowed into a thin line, so that a faint decorative pattern.

The record of transmission (denrai [伝来]): Murata Shukō [村田珠光] to Miyoshi Sōsan [三好宗三], to Oda Nobunaga [織田信長], to Ōtomo Sōrin [大友宗麟] until, in Tenshō 13 [天正13年] (1585) Toyotomi Hideyoshi requested it [from Sōrin], in exchange for which [Sōrin] was given the Nitari-nasu [似茄子]ᵏ and 100 silver coins (hyakkan [百貫]) in return. After the fall of Osaka Castle, Fujishige Tōgen [藤重藤元] and his son Tōgan [藤巌], were ordered to retrieve it from the ruins and restore it with same-colored lacquerʲ, after which it became Tokugawa Ieyasu’s [徳川家康] personal possession. It was subsequently bestowed upon the first head of the Mito-Tokugawa family [水戸徳川家], Yorifusa [頼房], and then passed down through his family [to the present day]. Today it is a treasure of the Mito-Tokugawa Museum [水戸徳川博物館].

The shifuku are made from brown ken-saki ume-bachi donsu [剣先梅鉢緞子], and dan-ori donsu [段織緞子]. There is [only] one lid. The outer box is made of unpainted paulownia wood. The hikiya [挽家] is black-lacquered. The gomotsu-bukuro [御物袋]ᵐ is made of navy blue kinran [金襴] with a pattern of small peonies and diamonds [小牡丹菱紋].

The Yamanoue Sōji ki [山上宗二記] has, “this jar is the finest katatsuki in the worldˡ. Together with Hatsu-hana [初花] and Narashiba [楢柴], it is one of the three [greatest] meibutsu under heaven” (kono tsubo katatsuki no tenka-ichi nari, Hatsu-hana・Narashiba to tomo ni tenka ni san-meibutsu no ichi nari [此壺肩衝ノ天下一ナリ、初花・楢柴と共に天下に三名物ノ一ナリ]).

__________ ᵃŌ-meibutsu [大名物]. Takahashi is using the traditional system of classification (proposed by Kobori Masakazu), where ō-meibutsu [大名物] refers to meibutsu utensils from the time before Rikyū; with meibutsu [名物] referring to those elevated to this status during Rikyū’s lifetime; while the term chūko-meibutsu [中古名物] designates meibutsu classified as such during (roughly) the first half-century of the Edo period.

ᵇKansaku-karamono [漢作唐物] despite the distaste that nationalist scholars have for the idea, the kansaku-karamono were made in Korea during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries; but more importantly -- and unlike the Chinese chaire -- they were specifically made for use in chanoyu. In other words, they conform, as closely as technically possible, to the teachings of kane-wari.

ᶜThe measurements in centimeters were provided by the editors who collated Takahashi’s material into this summary.

ᵈNi-sun go-bu-kyō [二寸五分強]: ...go-bu-kyō [...五分強] means that this chaire is ever-so-slightly larger than 5-bu -- so little that it was technically impossible to measure it.

The ideal large katatsuki, according to kane-wari, should be 2-sun 5-bu in diameter. In this case, since the glaze is fully vitrified, the increase was probably the result of a slight flow of glaze toward the widest part of the diameter during firing.

ᵉIn ancient times koshiki [甑] was the name of a simple kind of pottery still with an elongated and narrowing neck where the vapor was cooled into a distillate (later the word came to be used for a sort of ceramic steaming vessel, and this is the meaning generally given in dictionaries today). In chanoyu, it is used to refer to the neck of the chaire. Here the measurement refers to the height to which the neck rises above the shoulders.

ᶠThe kanji can also be pronounced rin [厘]. As a measurement, it means a tenth of a bu [分], or essentially 0.03 cm.

ᵍAlso written momme [匁], a traditional unit of weight (for things like pearls, paper, and silk). One momme is equal to 3.75 g.