chatnapwrites

429 posts

call me chat20 | ace | she/her

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

i wrote this little random blurb a while back. i don’t think it’ll ever make it into the final cut but it was fun to write from dylan’s pov and see them having fun together <3

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

Writer Beware makes posts on which publishing houses to avoid at all costs, which words to look for and which words to watch out for in contracts, and several other things that will keep you in control and knowledgeable about the publishing process. I’d suggest reading through the website if you want to avoid getting ripped off, cheated, or scammed.

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes u just need 2 listen 2 harry styles’ album fine line (2019) on repeat as u stare at the ceiling in the dark and have an existential crisis

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Morning After I Killed Myself

The morning after I killed myself, I woke up.

I made myself breakfast in bed. I added salt and pepper to my eggs and used my toast for a cheese and bacon sandwich. I squeezed a grapefruit into a juice glass. I scraped the ashes from the frying pan and rinsed the butter off the counter. I washed the dishes and folded the towels.

The morning after I killed myself, I fell in love. Not with the boy down the street or the middle school principal. Not with the everyday jogger or the grocer who always left the avocados out of the bag. I fell in love with my mother and the way she sat on the floor of my room holding each rock from my collection in her palms until they grew dark with sweat. I fell in love with my father down at the river as he placed my note into a bottle and sent it into the current. With my brother who once believed in unicorns but who now sat in his desk at school trying desperately to believe I still existed.

The morning after I killed myself, I walked the dog. I watched the way her tail twitched when a bird flew by or how her pace quickened at the sight of a cat. I saw the empty space in her eyes when she reached a stick and turned around to greet me so we could play catch but saw nothing but sky in my place. I stood by as strangers stroked her muzzle and she wilted beneath their touch like she did once for mine.

The morning after I killed myself, I went back to the neighbors’ yard where I left my footprints in concrete as a two year old and examined how they were already fading. I picked a few daylilies and pulled a few weeds and watched the elderly woman through her window as she read the paper with the news of my death. I saw her husband spit tobacco into the kitchen sink and bring her her daily medication.

The morning after I killed myself, I watched the sun come up. Each orange tree opened like a hand and the kid down the street pointed out a single red cloud to his mother.

The morning after I killed myself, I went back to that body in the morgue and tried to talk some sense into her. I told her about the avocados and the stepping stones, the river and her parents. I told her about the sunsets and the dog and the beach.

The morning after I killed myself, I tried to unkill myself, but couldn’t finish what I started.

By Meggie Royer

402K notes

·

View notes

Text

tbh i never deal with my emotions i just let them ravage my body and then i go to bed and then i wake up and do it all over again

256K notes

·

View notes

Text

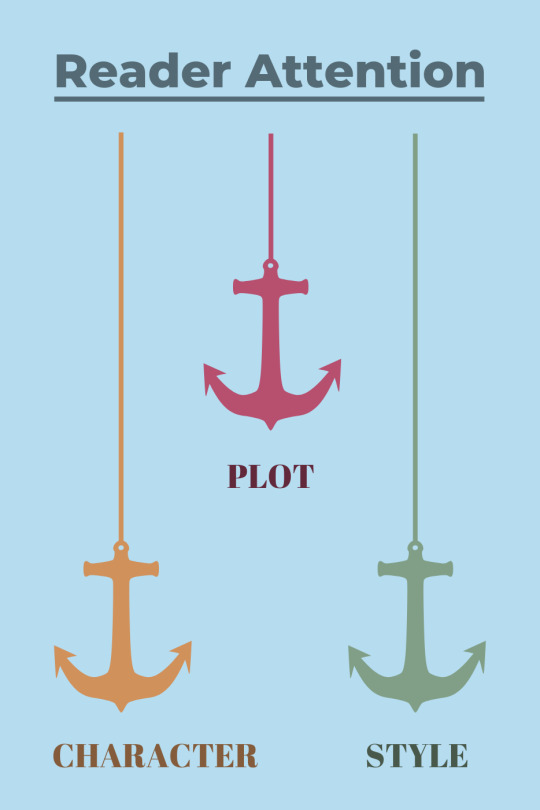

Narrative Anchors: How to hold your readers’ attention, wherever you take them.

One of my old fiction professors, Tom, used to always grab coffee with us students whenever our story had been workshopped.

We’d meet at the downtown coffee shop, where we fought the flocks of students for a table, pulled out a couple wrinkled copies of the story, and discussed feedback over bland coffee.

It was during one of these discussions that Tom pointed out something I’d stumbled into doing well. (He’s very good at that.)

“I think this is great, Mike,” he said, tapping my story on the table. “From the opening line, the question is whether these two will sleep together, and that grounds us. If my attention ever wavers, I can always fall back on, ‘Oh, well have they slept together yet? No, not yet? Okay, cool. I still know where we are, then, and where we’re headed.’ That makes the story easy to follow.”

This wasn’t, admittedly, a major focus of our conversation. We moved on to discuss more important things (like the story’s key flaws), but somehow that comment stuck with me over the years.

And now, looking back, I realize it was the first time I started thinking about something I’d eventually call “narrative anchors.”

What’s a narrative anchor?

It’s something I made up. But trust me, it’s helpful.

In short, I consider narrative anchors to be the craft elements you include in a story to ground your reader. On the one hand, they can help you craft a story that rings with simple, crystal clarity, and on the other hand, they can empower you to challenge readers with fresh, creative storytelling, without ever losing them at sea.

I put narrative anchors into three categories:

Plot Anchors

Character Anchors

Style Anchors

Plot Anchors

Plot anchors are a clearly defined situation, goal, or destination for a story. Tom (above) pointed out a situational plot anchor in my story, but you’ll find plot anchors everywhere. For example, in Avatar: The Last Airbender, Aang needs to master the four elements and defeat Fire Lord Ozai. We know from the beginning that defeating Ozai is the end-goal, so we feel grounded at every stage of the story, knowing where we’re going.

Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville, is another great example. Ahab is hellbent on hunting down the White Whale, and we never lose sight of that goal, even as the narrative stretches across hundreds of pages.

That’s the point of a plot anchor: to give your reader a clear direction, so they always know where they’re going.

Character Anchors

These anchors are the clear motivations and arcs you give your characters. Disney does this well in their musicals, always using an “I want song” (more about those here) to clearly declare what their main characters want: Mulan wants to express her true self, Hercules wants to find where he belongs, and so on. The rest of the story then circles around that character’s pursuit of their “want.”

When readers have a strong understanding of your character’s motivation and journey, they have a much easier time following the story as a whole.

Style Anchors

Style anchors are my handy little catch-all for every other craft choice you make to bring clarity and simplicity to your work. Style anchors can include: short chapters or paragraphs; simple and accessible language; straightforward writing forms; clarity of description; engagement with the five senses; using a smaller cast of characters; sticking to a single POV; and so on.

Cool. So when (and how) do I use these narrative anchors?

Tip 1: Don’t start with anchors. Start with the story. Take your idea, begin developing the characters and plot, and start writing.

Tip 2: As you write and revise, start thinking about anchors. Ask yourself what kinds of anchors you already have in place, what others may be helpful to add, and whether or not you’re doing enough to ground your readers in the story.

Tip 3: Consider your audience. Readers of popular fiction will want to be reasonably grounded, so you should try to always use at least a few anchors. But if your audience likes super artsy, experimental fiction, you may be able to get away with fewer tethers.

Tip 4: That being said, don’t be afraid to challenge your readers, whoever they are. If you want to get creative, go for it. If you want to experiment with form, language, plot, character arcs, or whatever, PLEASE do!

Tip 5: But when you challenge readers one way, try to compensate by grounding them in other ways. For example, maybe your story lacks a clear plot anchor, but you include a character with a clear arc and motivation. Or maybe your story is incredibly challenging on a stylistic level, but you give readers a clear character motive and plot (this was my experience reading Moby-Dick).

Tip 6: If big anchors don’t fit, consider smaller ones. For example, if your story lacks a BIG plot anchor like defeating Fire Lord Ozai, maybe use smaller plot anchors to drive individual sections of the book. Or maybe instead of a BIG declaration of your character’s motive at the beginning, include little anchors for your narrator that act like breadcrumbs for their motives and development.

Tip 7: Mix and match anchors as necessary, because there is no magic formula.

Long story short?

Write the story you want to write — then use narrative anchors to keep your readers reading, wherever your story takes them.

Tom may not have said that all in so many words, but if I bought him a coffee, I bet he’d agree.

Good luck, everybody, and good writing!

— — —

Everyone has stories worth telling. If you’re looking for writing advice or tips on crafting theme, meaning, and character-driven plots, check out the rest of my blog.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

There truly is a difference between "whispered" and "said quietly."

You can even write "said softly" or "in a low tone" and each evokes something slightly different when read. Do not take the No Adverbs advice so hard. So much of dialogue is tonal, so when you need a different word use it. Don't sacrifice meaning and character in important scenes for the sake of a "rule."

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

SOMEONE SENT THIS TO ME ANDI I CAN'T STOP LAUGIHIFJDJFND

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

tumblr's "year in review" has done nothing but alert me that I operate in an unnoticed dark corner of this hellsite

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

stop calling every piece of fabric with a plaid pattern “flannel”

flannel is a soft, warm cotton. it has nothing to do with what pattern is on the cloth

169K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Do World-Building Research

(Read this blog post and others on my website if you prefer)

Whether you’re building a fantasy world from complete scratch, or mentally designing the suburban house your very realistic story will take place in, at a certain point in your writing process you’ll need to plan out your story world. Here are a few world-building research methods to get you started:

Ask Questions

Ask anything and everything you can about your world. Each story will require different lines of inquiry. Listen to your story and follow the questions it seems to want you to investigate. What kind of car did your main character’s grandpa drive? How was the president elected? Why is everyone so obsessed with peanuts? The answers might appear in the story you’ve already written, in your imagination, or you may have to delve deeper into your research to find them. (For a complete list of questions to ask yourself as you build your world, check out the World-Building Checklist in my Free Resource Library.)

Draw a Map or Create a Model

Is your story world so complicated it’s making your head spin? Get out paper or other materials and make a visual representation of it. This could mean making a floor plan of your main character’s house, or mapping out an entire town, country, or kingdom. Physically creating your world is research in itself, but it can also guide you to new lines of questioning. You might discover that your story world contains a lot of lakes, or elk, or antiques, which in turn pushes you to research craters, or migratory patterns, or the history of antiques, which then leads you back to questions about meteors, or a lineage of hunters, or a family history of con artists, etc.

Outside Research

You may need to read history books, watch documentaries, conduct interviews, research online, or conduct first-hand research to get your questions answered. If your story takes place in Kansas and you’ve never been there, you could plan a trip, watch movies or read books set in Kansas, or talk to people who have lived there. Remember to record sensory details as well as facts. How does the air feel? What colors are prominent?

>>> Want more world-building help? Download a free printable World Building Checklist in my Free Resource Library! <<<

Take Notes

No matter what research method you use, take lots of notes. These can be straightforward recordings of the facts, or more creative expressions of what you encounter. Maybe something you stumble across will inspire you to write a poem, make a drawing, take a photo, create a mood board, or outline a new character. Keep in mind that your best ideas might come when you’re not actively researching, so keep a notebook or device nearby to record ideas that pop up when you’re not expecting them.

Use Your Own Experiences, Opinions, Ideas, and Imagination

Research doesn’t just mean looking into what other people say, think, or feel about a time, place, or topic. It can also mean exploring your own thoughts and perceptions! Say you’re researching a story that takes place in Oklahoma during the Great Depression. You’ll want to read history books, conduct interviews, watch films and documentaries, read novels set in that time period, research online, and perhaps even travel. But while you’re doing this, also pay attention to how you think and feel about the information you’re gathering. What details stand out to you? Does something you encounter make you mad? Why? What interests you about this time and place—and what bores you to tears?

When to Stop Researching

Some writers absolutely love story building… to the point that they never want to stop researching and actually write or revise their story! If you notice you’re procrastinating by languishing in the research stage, it’s time to get back to your story. As you return to the writing, you’ll probably find that you need go back to story building, then back to the writing, then to story building again. So don’t be too nervous about putting down your research: You can always go back and revise your world if you need to.

Of course, it’s completely acceptable to be obsessed with story building. All writers have their own attachments—elements of story telling that they love above all others. Some people get obsessed with a character, a plot, a setting, a theme… So if you’re a writer who loves your worlds, don’t be afraid to own it. Lots of amazing writers— especially science fiction and fantasy writers—are known for being huge world building geeks. If that’s what excites you, indulge! Just be aware of when you might be using it as a crutch because you’re nervous about composing or revising your story, and challenge yourself to move on—knowing, of course, that you can always come back to it if you need to.

>>> Want more world-building help? Download a free printable World Building Checklist in my Free Resource Library! :) <<<

Hope this helps!

//////////////

The Literary Architect is a writing advice blog run by me, Bucket Siler. For more writing help, check out my Free Resource Library or get The Complete Guide to Self-Editing for Fiction Writers. xoxo

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

the trouble with writing is that it’s literally always easier to just lie facedown on your floor and make inarticulate noises

366K notes

·

View notes

Text

Listen. Cut your own hair. Dye it blue, then shave it off when you’re bored of it. Wear that outfit with those shoes. Paint your nails with all the colors of the rainbow. Get that tattoo. Go to the movies alone. Get coffee, then drink it at that special place you like. Mouth the words of the song you’re listening to on public transport. Put that thing on your wall. Bake. Draw. Dance in your underwear. Life is so much better when you don’t give a fuck

279K notes

·

View notes