Text

Recipe: Hot Chocolate

Photo source:

https://www.travelawaits.com/2489668/oaxaca-city-is-a-chocolate-lovers-dream/

One of today's most infamous chocolate delights would have to be Hot Chocolate, cultures all around the world have added their own style to the beverage and have truly made it their own. Although many people may not know about the history of where chocolate originated from, hot chocolate has to be the oldest chocolate delicacy to date. Before we begin with the recipe, we can first take a look at the origin of cacao and “hot chocolate” and where it derives from. If we take a look at previous blog posts we can see that one of the first societies to ever use cacao in general were the Maya in Mesoamerica. The Maya peoples were the first to ever record their use of cacao through glyphs, and researchers found that the majority of their ceramics were engraved with the words “beverage”, “cacao”, etc. Many of these vases had stored cacao, and were all used for specific occasions and purposes and were mainly in the hands of nobles and elites. Very rarely was cacao in possession by the lesser peoples, as it was mainly consumed and in the hands of the wealthy. Most of the time the cacao beverage that was popular in the Maya society was served in banquets and feasts that were economic, social, and political bonding strategies to gain alliances. During these banquets cacao was not only gifted but received, it was a currency for the Maya culture that could be traded for other specific goods or to be used as tribute to the royal throne. It was a luxury to enjoy cacao, as it was also seen as an important trading commodity and tribute. Cacao was not only a sign of power but a symbol of wealth, it demonstrated sophistication, elitism, power, it embodied luxury in all aspects. Maya enjoyed drinking the cacao beverage in specific “chocolate bowls”, that were hand crafted and painted for that specific occasion. These bowls were specifically designed to prepare the cacao while it was in its liquid state, because of the long sprout as the beverage was poured from one bowl to the next it allowed for the cacao to be mixed into the frothy, velvety, flavorful beverage the Maya enjoyed so much. It was rare when the Maya mixed other ingredients into their cacao beverage, tzih kawkaw, but if they did they would add chili, honey, cornmeal, vanilla, annatto, and certain flowers to enhance the flavor of cacao. The Mexica also did little to enhance their version of the cacao beverage, the only significant difference was that they enjoyed it hot or lukewarm rather than in a cold state. If the beverage was hot then it was able to enhance the flavors that were added into the cacao like: vanilla, Kapok tree, seeds, chili, and anatto as a coloring agent. Not only did heating the beverage allow for the enhancement of the flavors, but it also allowed for the cacao to become thicker (with the help of cornmeal), this version of the cacao beverage is notably called atole, and is still popular and made today. In Venezuela, prior to the arrival of the Spanish, there was also a version to the cacao beverage that the Maya and Mexica enjoyed, it was a fermented-maize drink that was referenced as chicha. But as Europeans colonized Mesoamerica, and acquired the taste for cacao the flavors and recipes began to change. In Spain during the 17th century, the Spanish elites and nobles enjoyed their own version of the cacao beverage oftentimes drinking it out of a mancernia (which is a plate or saucer with a collar like ring in the middle that a small cup would be sitting on without the possibility of having it slip), they mixed the cacao with sugar, cinnamon, vanilla, and acciote (which added color to the drink). Later in the 19th century would the Spanish learn to mix the cacao with alkaline salts to remove the bitterness and make it more soluble in water. As for Italy, they too followed in the Portuguese and Spanish \ footsteps in welcoming cacao into society, although their main reason was because they owed it to the great glory of god to participate in cacao trade. One of the more significant differences the Italians did with cacao was mixing the beverage with jasmine, their recipe is as followed: 10lbs of toasted cacao beans, fresh jasmine flowers, 8lbsof sugar, 3oz of vanilla, 4 to 6oz of cinnamon, and 2 scruples of ambergris. As for today there are many different recipes, styles and techniques that can be followed to make the perfect hot chocolate. Some may use a packet of hot cocoa powder and mix with warm water or milk, other might use the brand Abueltita or Ibarra. Both of these brands are made in Mexico, but the only slight difference is that Ibarra carries a more cinnamon flavor to it in comparison to Abuelita. Both packages contain several chocolate tablets, and all you have to do is add it to either boiling hot water or (non-dairy) milk, mix it until it has completely dissolved and enjoy. But if you would much rather have a homemade version the ingredients are quite simple: 3 cups of (non-dairy) milk, 3 tablespoons of crushed cinnamon, 6 ounces of semi sweet chocolate chips, 3 tablespoons of granulated sugar, ¾ teaspoon of vanilla extract, a pinch of salt and ¼ of chile de arbol, or cayenne pepper (which is optional). After all your ingredients are collected you must first simmer the milk, adding the cinnamon as you do. Once you can smell the cinnamon your next step is to whisk in the chocolate, vanilla, salt, sugar, and cayenne pepper in. This should take about 5 minutes, and once you are finished you should be left with a smooth and creamy finish. After that your last step is to serve your hot chocolate and enjoy.

Bibliography:

De Orellana, Margarita, et al. “Chocolate: Cultivation and Culture in Pre-Hispanic Mexico.” Artes De México, no. 103, 2011, pp. 65–80. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24318969. Accessed 19 Nov. 2020.

De Orellana, Margarita, et al. “CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends.” Artes De México, no. 105, 2012, pp. 73–96. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24319003. Accessed 19 Nov. 2020.

“Mexican Hot Chocolate Inspired by 'The True History of Chocolate'.” Strong Sense of Place, 23 Jan. 2020, strongsenseofplace.com/food_and_fiction/2020/01/23/mexican-hot-chocolate-inspired-by-the-true-history-of-chocolate/.

0 notes

Text

Chocolate Futures: Fair Trade and Deforestation

Photo Source:

https://perfectdailygrind.com/2018/03/roast-fine-cacao-beginners-guide/

According to the Washington Post in a 2019 article, in the past decade alone, deforestation has accelerated in West Africa where over two-thirds of the world's cocoa is produced. They also reported that compared to anywhere else in the world, in 2018 the loss of Tropical rainforest accelerated in Ghana and the Ivory Coast. Globally deforestation is an issue, but the production and demand of cacao (palm oil, soybeans, timber, beef, rubber) allow for 40 football fields of tropical rainforests to be lost every minute. The Ivory Coast alone has lost over 80% of its rainforest in the past 50 years, and in Ghana trees have been completely removed that spreads across an area as big as the state of New Jersey. Although many different corporations, manufactures, and goods have played a huge part in the deforestation of our tropical rainforests, thousands of cacao farms that are often set in rainforests and national parks do the most damage. Many of these farmers are using land that should be protected but are exploited by corporations to use for their benefit. To add to the issue of deforestation, many of the trees that are removed for the purpose of making more land for cacao farms are left there and release carbon into the air. This now leads to the result of deforestation releasing 10% of global greenhouse emissions. This deforestation, and along with the child labor has made many of the big name brands that manufacture chocolate to have a loss of credibility an ruin their image (for the most part). This is then why many of these big chocolate manufacturing companies have created policies and worked deals with the United States and African government to help aid in restoring Africa and in the deforestation crisis. But over the past few years no one has completely checked these companies and the deadlines, allowing for no real affirmative action to be done. In addition to better sustainability in these cacao farms, and trying to limit the issue of deforestation, fair trade is also a major issue that needs to be addressed and fixed within the production of cacao. Many of these farmers who are cultivating the land of these cacao farms rarely profit off of their work, and can barely afford to take care of their families. Majority of today's contemporary trade stems from the structural roots of colonialism, which was that “cacao was supposed to be cheap” and the labor used behind it was supposed to be lucrative (Leissle 128). This is why it is important to push for fair trade in chocolate companies, but also that the farmers who are producing these cacao beans are being paid what they deserve, which means that not only is the fair trade important but that it is free trade, organic, and direct trade. It is important that the brands who take part in the cacao productions are ethical in their “fair trade” methods, and truly try and help the farmers who produce their crop.

Bibliography:

Leissle, Kristy. Cocoa. Cambridge, England. 2018

Mufson, Steven. “Mars Inc. Wants to Be a Green Company. The Problem Is Where Its Chocolate Comes from.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 29 Oct. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/national/climate-environment/mars-chocolate-deforestation-climate-change-west-africa/.

0 notes

Text

Chocolate in Modern Times: Expansion of Consumption and New Social Identity (Trading Cards, Women, Chocolate Museums)

Photo source:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/short-rise-and-fall-crazy-cocoa-trade-cards-craze-180954113/

Many of the companies that produced chocolate relied heavily on the social culture of their consumers to better advertise and showcase their products. In other words many of these companies found ways to cater to the likeness of their consumers, which is where trade cards and museums stem from. To begin with the trade cards, many of them delivered clear messages that showcased a sort of power that words did not have, these visuals evoked a message “cleanliness, industriousness, and an appreciation for good food and drinks'' into society's culture (Westbrook 187). Many of these companies that produced these cards targeted children specifically, seeing that they were the easiest focus group to take advantage of. Oftentimes these trade cards had images of children printed on to them that “...suggested innocence, delicacy, and, by extrapolation, purity” (Westbrook 187). There were also images of the “perfect family” happily sitting together in a living space, enjoying one another's company. Another marketing strategy was the marketing of chocolate to women, to help them be “good nursing” mothers. Depictions of a woman laying with her baby in these trading cards and a cocoa product accompanying them. Oftentimes words like “pure”, “digestible”, “soluble”, “dietetic”, “nutritious”, “healthy”, “invigorating”, and “delicious”, were used in slogans to make consumers feel more comfortable using these products. Through the years chocolate was often seen uncivilized because of wear cacao came from, and it was heavily stigmatized as a sexual temptation to its consumers. As marketing helped deteriorate that stigma it helped in the sales of these chocolate manufactures as well, selling the idea that chocolate can also be used for romance as it could be for health and energy. Thus in the 20th century marketing specialists connected chocolate to the importance of courtship. This is where we begin to see the “romanticization of commodity and commodification of romance” (Nutter 199). Along with romance, chocolate was especially targeted to women to not only be great mothers, but to also physically look and feel great. This is where we also begin to see the development of white women's history in America, and what they represent in society. Women are starting to be showcased as objects and pushed into fitting these stereotype roles that manufacturers created. “These representations of women reflect their perceived social roles and lived experiences at a particular historical moment” (Nutter 200). Like many other goods, selling chocolate often became a strategic marketing competition to become desired by the masses. The trade cards were short lived and by the beginning of the 20th century advertisement shifted onto more collectible and premiums like cigarette and bubblegum cards (Westbrook 189). Aside from trading cards in the late 1800s chocolate manufacturers turned to displaying their work in Agricultural halls, or “chocolate museums”. These showcases would often exhibit different types of machinery, like a panning machine for coating nuts with chocolate, marble topped production tables, cutlery, papermaking, and even trading cards. Chocolate manufactures also realized that these showcases were a valuable moment to sample their products, and further market their companies.

Bibliography:

Nutter, K.B.. (2008). From romance to PMS: Images of women and chocolate in twentieth-century america. Edible Ideologies: Representing Food & Meaning. 199-222.

Westbrook, Nicholas. (2008). Chocolate at the World's Fairs, 1851–1964. 10.1002/9780470411315.ch16.

Westbrook, Virginia. (2008). Role of Trade Cards in Marketing Chocolate During the Late 19th Century. 10.1002/9780470411315.ch14.

0 notes

Text

Cacao in Modern Times: Globalization of Product

Photo source:

https://fortune.com/longform/big-chocolate-child-labor/

For much of cacao's early expansion into European countries the crop was planted and grown in the Americas, with much of the labor force being indigenous peoples, and slaves that were imported from Africa. But as popularity increased so did the demand for chocolate, and during the mid 1800’s “the cacao trees of the Caribbean and the Spanish Americas were depleted and disease ridden: colonists destroyed the Theobrama stock through overproduction and poor management, just as they had ravaged the populations that had taught Europe about cacao” (Off 57). But as colonists discovered how well the cacao crop thrives and grows near the equator, they decided to relocate their business into other countries that were also located near the equator. The Dutch moved their cacao stock into Indonesia, and the Portuguese discovered how ideal the terrain in the Gulf of Guinea (present day Cameroon, in Central Africa) was for the production of cacao. “For years they'd been transporting Africans to the Americas to work as slaves on cocoa farms. Now they’d take the cocoa trees to Africa. One thing wouldn’t change: the Africans would continue to work the cacao farms in appalling circumstances” (Off 58). Majority of the slaves who worked on these cocoa farms in the 1800s were seen as “indentured servants”, they were not necessarily forced into working and could leave at any time but many (if not all) slaves could not afford to do so and were rarely told that they could leave if they wanted to. These cacao plantations offered nothing but abuse and torture to the salves, often times being treated inhumanely by their “owners”, “...squeezing their fingers in copying press, cutting parts and ears off, thrash them, men, women heavy in the course of nature, and children so unmercifully” (Off 59). Going into the 20th century Africa was hurting economically, and although these African workers were still subjected to work with earring less and less for their beans they paid for it physically by the pesticides and herbicides that the British imposed onto the crops (Off 107). As for the 21st century, to this day these cocoa farms are still being maintained and worked mainly by men and young children. Young boys and girls as young as ten or thirteen years old are being manipulated into working these farms. Many of them believed they would be going to school, and getting an education only to be lied to and driven into these plantations. These boys work long hours, months on end to provide for their family. Many of the young boys who work are also told to lie about their age so that no one is caught in these illegal activities. Many of today's big chocolate company brands know of this child labor issue, and yet do little to nothing about it. Although many of these companies have stated to set deadlines and policies that will help eradicate the use of child laborers, those deadlines and policies have gone unchecked and often overlooked.

Bibliography:

Off, Carol. Bitter Chocolate. University of Queensland Press, 2008.

“Hershey, Nestle and Mars Won't Promise Their Chocolate Is Free of Child Labor.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 5 June 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/business/hershey-nestle-mars-chocolate-child-labor-west-africa/?fbclid=IwAR0Wylrl4K2btGprh_qMmdd5lhdz4w5SdPTa8kNdUCgQ7T9uuyZKYk65GWw.

0 notes

Text

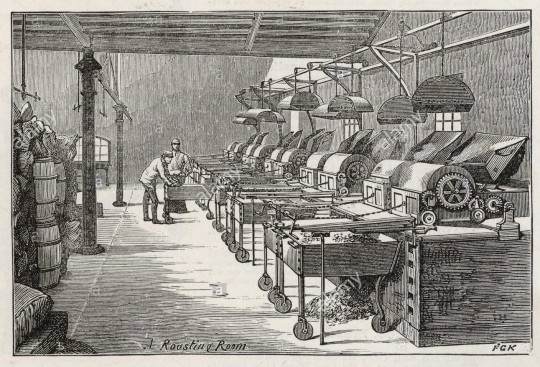

Chocolate factory: Technological Revolution

Photo source:

https://www.alamy.com/frys-factory-roasting-image8262683.html

The method in which cacao has been prepared has stayed the same through it’s evolution regardless of how people have modified it to make it their own, varying its flavor, quality, characteristics, etc. Aside from the obvious changes that have occurred to chocolate, through its flavor, production, and manufacturing, the key steps have remained enact for its development and remain to this day; roasting, winnowing, milling, molding (Snyder 611). Prior to Europeans getting ahold of cacao, the Mexica method of producing chocolate was quite simple, “[they would] roast the kernels in earthen pots, then free them from their skins, and afterwards crush and grind them between two stones, and so form cakes of it with their hands” (Snyder 611). These key steps that the Mexica perfected, are the same steps that have been used by the Europeans and are the same steps that influenced a more efficient and mass producing manufacturing process. Not to mention that the Spanish also added their own flavor into their method of producing chocolate, often adding sugar, vanilla, and cinnamon during the milling step to “allow for good mixing with the liquor” (Snyder 612). In the 18th century when chocolate was demanded in high volumes, most of the time it was consumed as a liquid beverage but it was noted in the 17th century that it was also offered in solid form.

One of the first European technologies invented to aid in the efficient development of chocolate was a hand turned cylinder bean roaster, and also a stone metate that was used to grind cacao beans. Both were developed in the early 1900s and were introduced by Spain and Portugal (who were the power houses of cacao trade). Depending on the country's methods of production and manufacturing of cacao, all the outcomes of the different chocolate would be diverse by flavor. In France “the beans were roasted at higher temperatures and for longer periods of time and were described as producing chocolate that tastes like burnt charcoal” (Snyder 612), while in comparison to Spain and Italy who had more bitter aromatic flavors. To perfect the best chocolate was one of Europe's most intense competitions, entrepreneurs, scientists, and chocolate companies were racing one another to see who could come up with the best methods and procedures to perfect the creation of chocolate. One of the most popular procedures produced was the conching method that was developed in 1879 by Rodolphe Lindt in Berne, Switzerland. Due to insufficient drying and roasting of cacao, a white substance formed over Lindt's chocolate and with the advice of his brother “modified an old water powered grinding machine… embedding iron troughs in granite with the upper edges curved inward. The curved edges allowed for more chocolate mass to be added to the trough without splashing out. The aeration reduced the bitter and sour flavors and helped to develop the chocolate aroma...When eaten, this new chocolate melted on the tongue and possessed a very appealing aroma. In this way began the production of chocolate fondant” (Snyder 616). With this new development Lindt knew he had to keep this method of “conching” a secret so he was ahead of his competitors in the creation of chocolate technology.

Bibliography:

Snyder, R., Olsen, B.F. and Brindle, L.P. (2009). From Stone Metates to Steel Mills. In Chocolate (eds L.E. Grivetti and H.‐Y. Shapiro). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470411315.ch46

0 notes

Text

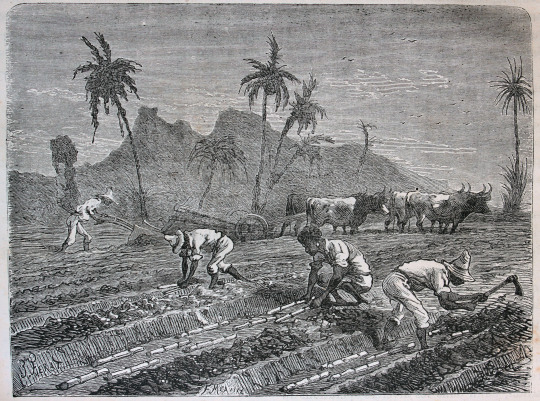

Cacao in Colonial Times: Production in the Americas (Venezuela)

Photo Source:

https://www.caracaschronicles.com/2015/11/06/what-was-venezuelas-colonial-economy-like/

It was during the 17th century that the province of Caracas, Venezuela would have cacao become the region's most foremost item of trade. As cacao became more available to Europe in the 16th, by the mid and late 17th century there was a more substantial demand for the crop. Before Caracas became the supplier of cacao for Spain, Spain originally acquired its cacao supply through Amsterdam. But by the 18th century Venezuela’s Caracas Company became the “legal link between the Spanish cacao market and the cacao economy of the province of Caraca” (Pinero 77). Prior to the 17th century there has been no record or official documentation of cacao being a native plant to Caracas, and for that reason it is commonly presumed that cacao is is not a native tree of Venezuela and was “planted there by native and African laborers at the command of Europeans” (Ferry 611). Within the span of 50 years cacao would become Venezuela's most popular traded good, although it is questioned how Venezuela was able to become a significant trader and supplier of cacao in New Spain when cacao was not a native plant in Caracas. Much of this success in cacao trade can be owed to the labor force used to create new groves during the early 1600s for the cacao crop, “much of the work of clearing and irrigating the land was done by African slaves who, in all probability, had been purchased with profits made in the 1620s and 1630s…” (Ferry 613). Due to the weather in Caracas, cacao was able to thrive in the region. The conditions were perfect for the growth of the crop, which also aided in Venezuela's ability to join in the trade and supply of Europe. “Here the conditions are ideal for cacao cultivation… winds release moisture accumulated during the Atlantic crossing as they collide with coastal mountains, providing a moderate, but constant, supply of water to the hot, cloud- covered valleys that rise steeply from the sea's edge” (Ferry 615). As the company began to gain such popularity it was important to keep track of the net sales and profit of the company, for every “fanega” (or roughly 55 liters) was approximately 40 pesos. Also like anything else in the economy, as cacao imports increased, retail chocolate prices went down (and vice versa) (Pinero 80). But most of those who could afford cacao were those who were of higher class, “A Parisian exclaimed in 1768 that "the great take it [chocolate] sometimes, the old often, the people never” (Pinero 83). What this meant was that normally an unskilled labor in Pairs earned about 145 maravedis daily in 1737, but the cost of a pound of chocolate was more than twice that amount (208%), running for around 300 maravedis (Pinero 83). If a cabinet maker in 1742 made about 636 daily, he could roughly afford to purchase two pounds of chocolate. With these calculations it is easy to tell the income level, and status that the consumers of chocolate were in Europe during the globalization of cacao.

Bibliography:

Ferry, Robert J. “Encomienda, African Slavery, and Agriculture in Seventeenth-Century Caracas.” The Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 61, no. 4, 1981, pp. 609–635. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2514606. Accessed 20 Nov. 2020.

Pinero, Eugenio. “The Cacao Economy of the Eighteenth-Century Province of Caracas and the Spanish Cacao Market.” The Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 68, no. 1, 1988, p. 75., doi:10.2307/2516221.

0 notes

Text

Chocolate in Colonial Times: Consumption in Europe and the Americas (Portugal and Brazil)

Photo source:

https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2015/01/06/18th-century-drinking-chocolate/

With the expansion of cacao, or Chocolate, many countries began to indulge in its properties of healing and stimulation. As stated by Timothy Walker in Cure or Confection, the Portuguese king and his advisors noted the “double light” that cacao held. It was a healing plant, essential to the health and well being of soldiers who protect the empire, and a stimulating aphrodisiac enjoyed by the “highest class, lineage, and privilege”. It was during the 18th century, where the Lisbon monarch employed a Chocolaterio da Casa, or a royal chocolatier, that was skilled in the knowledge of both the culinary, and medical roles that cacao holds. The chocolaterio was in charge of handling, managing, obtaining, and preparing the cacao, creating chocolate delights that are to be enjoyed by the royal family, advisors, and nobles. While preparing these chocolate delicacies, the chocolaterio also supplied invalid troops with a cacao beverage that was to help them recuperate their strength. This is also where the chocolaterio would experiment with the medicinal properties that cacao holds, often times “extracting the valuable medicinal cacao butter provided to interned patients for their skin disease…” (Walker 561).

The reason that the Portuguese were able to extract the medicinal properties of cacao can date back to 1549, when Brazil became a colony of Portugal. It was in the 16th century where contemporary Europeans “already considered cacao one South America’s most important medical plants” (Walker 562). To the society of Jesuits in the 16th century, cacao’s possession of medicinal richness was vital and they learned most of their information through the indios of Brazil. The indigenous tribes, Tupi and Guarani, had known of these properties long before the Europeans arrived, educated on of the mild stimulant that cacao carries and the sustaining energy it holds to withstand hunger and fatigue. While the Jesuits studied the Tupi and Guarani, and several other indigenous tribes in Chile and Brazil, they were able to compile a detailed manuscript volume of native remedies that was over 230 pages. The first of these entries begin with “Virtues of Cacao”, which go into detail of the medicinal usage of cacao. In one entry it explains how with just an ounce of prepared chocolate was enough to “‘open the [body's] passages… comfort the mind, the stomach, and the liver, provide aid to asthmatics… and those with cataracts, and maintain the body incase of cold’” (Walker 563). With this knowledge, it only added to the incentive that cacao must be gathered and further cultivated for their “health purposes in their mission communities…” (Walker 563). It is to be noted that most of the symptoms that were stated earlier were suffered by the Europeans, and not the people of the Tupi and Guarani tribes. This knowledge that the Jesuits stumbled upon was one of the main reasons as to why cacao would begin to be so popular in the Portugal colony, as well as Portugal itself.

Bibliography: Grivetti, Louis, and Howard-Yana Shapiro. Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. Wiley, 2009.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chocolate Encounters: Mexica and Spaniards

Photo source:

https://chocolateclass.wordpress.com/2015/02/20/drink-of-choice-mesoamerica-to-europe/

It was the “encounter” between the Mexica and the Spaniards that would be the start of the crops globalization. Cortez saw how the Mexica enjoyed cacao in the form of “Hot Chocolate '', of course it was not exactly called hot chocolate it was simply a “____ cacao beverage or altaquetzalli, “precious water”. The Mexica, who dominated much of Mesoamerica in the 16th century, had a large supply of cacao. Mainly due to the fact that they obtained much, if not all, of their cacao beans through tributes, while some were received through regular trade and once Cortez had acquired a taste for cacao, Europe would soon quickly follow. It was the fall of the Mexica empire that allowed for Cortez to take advantage of this economic opportunity, and use the cacao tribute to profit at his own gain. The Spanish military easily gained control of Mesoamerica, and the throne undoubtedly continued the “cultivation, commerce, and consumption of cacao, because the Spanish rulers' [knew of their] immediate ability to profit from the conquest” (Norton 676). Essentially the growth of the Spanish empire all “depended on their usurpation and maintenance of the tribute system organized by the Aztec rulers” (Norton 676). What history fails to mention, is that one of the main reasons cacao was so easily accepted into European society, is because of the development of a new social organization. Many of the conquistadors who colonized Mesoamerica saw themselves outnumbered by the indigenous, and also a severe lack of European women. So due their dependency of native culture, which led to their basic survival in Mesoamerica, many of the conquistadores adopted native dietary and domestic practices. It was the beginning of this cross-cultural contact, where indigenous women were now servants, housewives, but also the backbone of cacao consumption. They were the ones to prepare cacao in pre-Columbian and colonial Mesoamerica ((Norton 677). Once European women began to flood Mesoamerica, these women were still at the center of society, and with that cacao. It was in the household, and the continuation of the indigenous following pre-Columbian traditions of gifting cacao, and in the marketplace that would continue the popularity of cacao. The marketplace in Mesoamerica societies was also a place in which cacao thrived, much of the knowledge was also obtained by women. As said by Marcy Norton in Tasting Empire, “women—particularly Indian and black women—became the purveyors of desirable knowledge and edible and potable substances, while Spaniards were the seekers and buyers”. During the 16th century small batches of cacao would be delivered into Spain, but it was during the end of the century that cacao would begin to take over Spain and especially in the city of Seville. By 1650 and 1700 over 7 million pounds of cacao would be shipped into Spain, and through the several clergy and merchants that traveled between the New and Old world, would the Seville elites soon acquire a taste for the cacao. Which would then lead to the massive consumption in Europe.

Bibliography:

De Orellana, Margarita, et al. “CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends.” Artes De México, no. 105, 2012, pp. 73–96. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24319003. Accessed 19 Nov. 2020.

Norton, Marcy. “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics.” The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 3, 2006, pp. 660–691. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ahr.111.3.660. Accessed 19 Nov. 2020.

0 notes

Text

Origin of Chocolate

Photo source:

https://mayacacao.com/

The history of Chocolate goes far beyond the growth of Chocolate companies, past capitalization, and colonization. “Chocolate” was never originally named Chocolate, that name occurred through the appropriation and colonization of the indigenous crop Cacao. To begin, Cacao can be traced back to Mesoamerica, Central America, and specifically to certain indigenous communities like the Olmecs, the Maya, and later the Mexica. Cacao before it became capitalized was used by Mesoamericans for its nutrition, medicinal aid, artistic influence, commercial usage, and spiritual purpose as stated by Margarita de Orellana in Chocolate: Cultivation and Culture in pre-Hispanic Mexico. Although not much can be said for the Olmecs in how they cultivated Chocolate into their society, it is noted that though classic Maya scribes they were one of the first societies to ever write about the subject of cacao. The Maya wrote mostly through glyphs, and engraved their thoughts through jewelry, stones, ceramics, etc. It was the ceramics especially, where scholars were able to indicate how the Maya utilized cacao. First it was noted that many of these vases were created and intended for the use of elites, the art of glyphs and engravement on ceramics stipulates that mainly elites had the luxury of enjoying cacao. Second, these glyphs on the vases stipulate what was contained in the vase. As said by J.M. Hoppan in The Maya: the first Chocolate Scholars, many of the inscriptions said “for’, “bowl”, “beverage”, “cacao”, “____ cacao”, “bowel for cacao-atole”, “fresh cacao’, “cacao bowl”, “frothy cacao”, “chili cacao”, etc. The evidence of cacao used in the Maya society dates back to 600 BC, and not only was it used by nobility for food but also as a gift giving luxury to “establish alliances, build strong social ties, and define a certain hierarchy”. The cacao was also served as a beverage during these specific feasts, as a social, political and economic strategy to establish bonds between the banquets. During these banquets cacao was not only gifted but received, it was a currency for the Maya culture that could be traded for other specific goods or to be used as tribute to the royal throne. The elites were also “generous” with their cacao, and often during these feats paid those in the lower rank for their services. Philipee Nondedeo author of Cacao in the Maya World: Feasts and Rituals” claims that “Feats thus permitted wealth to be redistributed from the heart of the city to its periphery, from the upper echelons of the hierarchy to its lower rungs”. Cacao was not only a sign of power but a symbol of wealth, it demonstrated sophistication, elitism, power, it embodied luxury in all aspects. The role of Cacao in society would soon begin to fall out of significance once the Spanish began to exploit the crop.

Bibliography: De Orellana, Margarita, et al. “Chocolate: Cultivation and Culture in Pre-Hispanic Mexico.” Artes De México, no. 103, 2011, pp. 65–80. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24318969. Accessed 19 Nov. 2020.

2 notes

·

View notes