Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

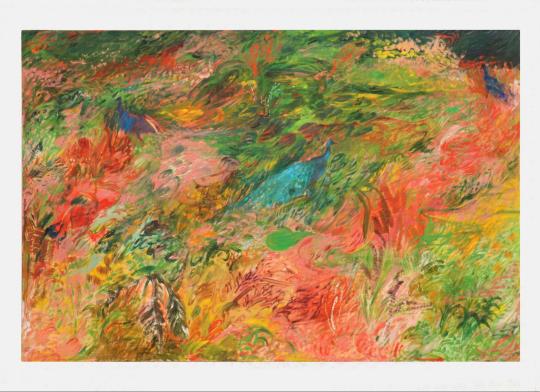

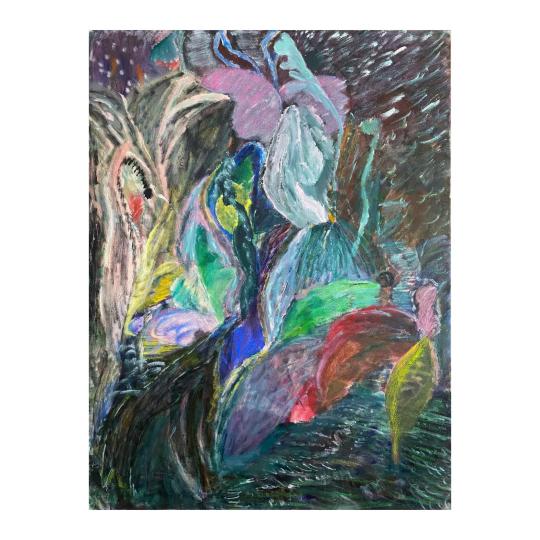

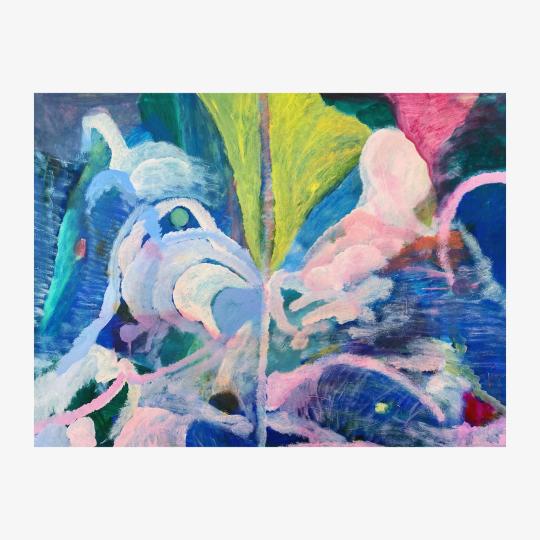

30. Mónica Palma & Kemar Keanu Wynter

Mónica Palma and Kemar Keanu Wynter discuss their recent work, how they are Invoking memories of food and home, the relationship of the body to their choice of materials and processes, trusting the wisdom of their bodies in making the work, how their thinking has evolved regarding making work for a white gaze, and how truth and honesty play roles in their work.

This conversation happened in person in the Winter of 2023, the text was edited for the purpose of the Correspondence Archive Project.

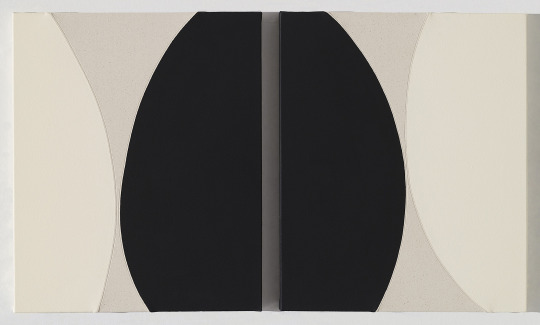

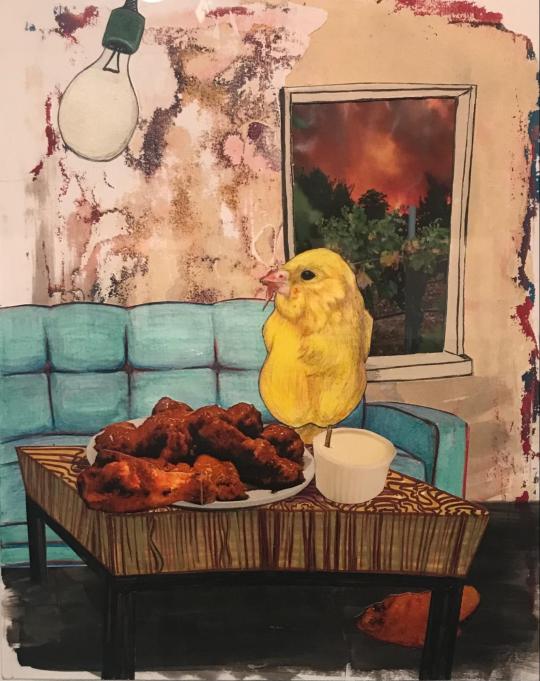

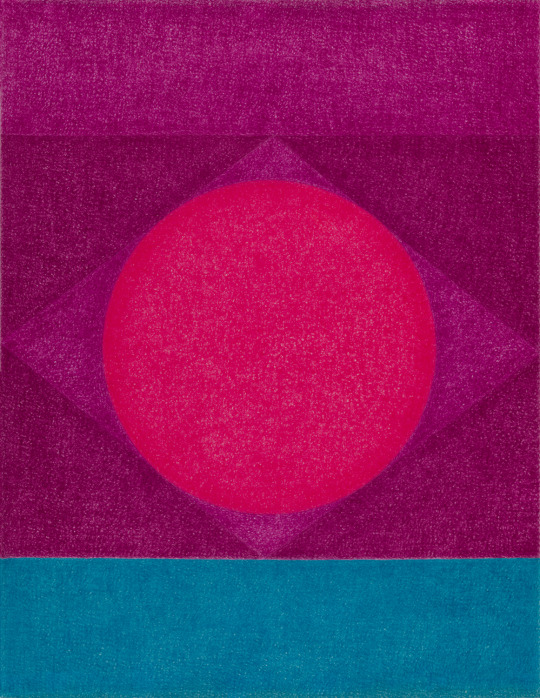

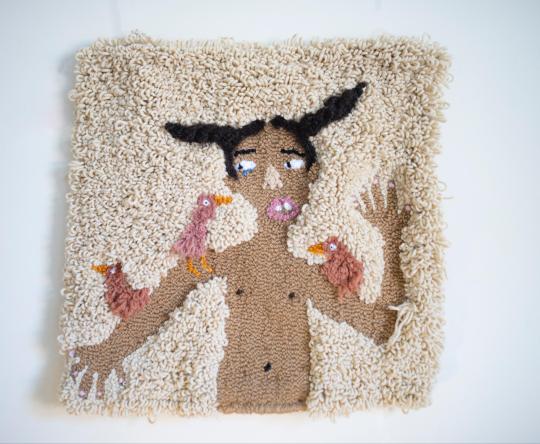

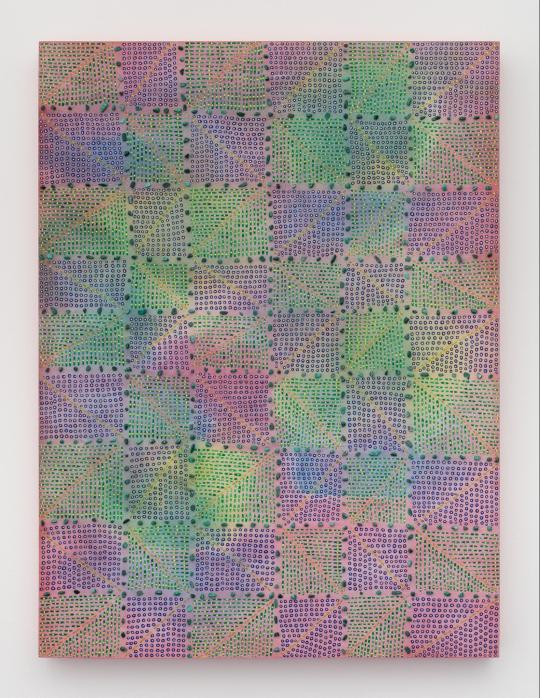

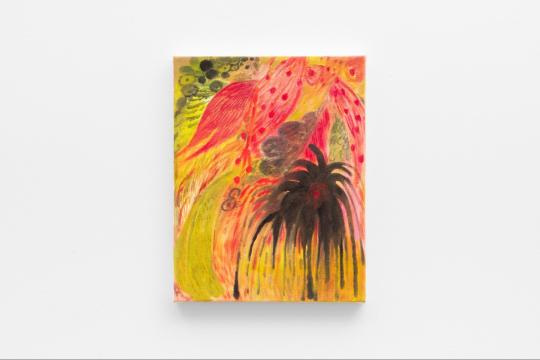

Kemar Keanu Wynter, (II.) Rederrin, 2022, Oil pastel, acrylic, graphite and grommets on collaged French cardstock, 35.375 x 36.25 inches

Mónica Palma (MP): Let's see. Hello. Okay, so we are in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Tell us who you are?

Kemar Keanu Wynter (KKW): My name is Kemar Keanu Wynter and I’m happy to be talking to Mónica today.

MP: So here I am. I'm Mónica Palma. And I'm so happy that you're here! I knew you were coming and I'm aware that I live in the neighborhood where you grew up - Crown Heights. That's your place. Before opening this recording app, we were talking about place, location, and neighborhoods. We talked about neighborhoods changing and transforming. We were talking about mulberry trees in this neighborhood whose fruits are edible. And I know that in your work one of the biggest anchors is food, your neighborhood, and your family. I wanted to ask you, because I know that you were in a residency recently. What happens when you are far away from your location or the place that you consider your location at heart? How do you access those familiar forces? How do you remember actions? Do you think that those forces are embedded in you when the place changes and you find yourself in a different location? And if so, how do you access those sources, those powers?

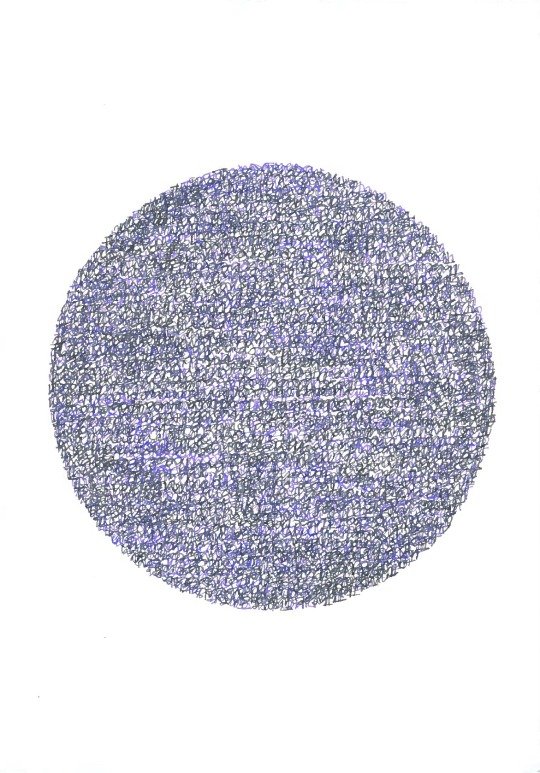

KKW: Whether I'm home or traveling, be it a residency or just out of the city for any other reason, if I'm working on paintings based around the dishes that I grew up eating, generally the way that I try to pull back to that–I mean the process generally doesn't really change depending on where I am–is through the recalling of memories. You know, my experiences with these dishes within mine or my auntie’s apartments, which are just second, third homes. The best way to do that is through writing. Text has become a big part of my practice and it's something that I think I've refined and become more attuned to in the last year especially. I will start thinking about my experiences of the dish, the flavors, the heat, the conversations and ambiance around it– I feel like every single dish has a story attached, some have multiple stories that can be attributed to very specific, singular moments in my life. I just write about those moments, and that helps me figure out where my focus needs to be when it gets to the painting side of things.

From the jump I knew that I couldn't just be a freely working abstract painter, I always needed something to ground the work, right? Having that text, something that really serves to bring those memories from years back to the forefront of my mind… it’s crucial for me to hone in on those memories and use it as the nucleus for my practice and then reach out from there. There's definitely a point in my process where the painting becomes as much about the dish as it is about making a formally good painting. And so there’s this moment where the narrative I’m bringing to the dish evolves into this dialogue with the surface about what it takes to make this work a good painting, but I wouldn't be able to get to a finished painting at all without having those initial references at the foundation.

MP: You mentioned the words nostalgia and memories. When you travel into the past to access specific forces, they will help you carry the work, but you also have to anchor yourself in the present. Then when you were talking about the formal qualities, the interest in making a good work, and your personal ethics. For me, it's like you're mixing those two tempos, right: the past and the present, like perhaps the time traveling sometimes takes you to sad or happy places, but then you bring the work to the present, and you give it roots and feet and work that comes back here and has its own flesh and its own identity.

I was wondering if the topics of food and family become beliefs? When I think about my work and how I don't have a religion and I don't live in my country, and as a result, there are certain things, certain materials, certain memories, that I invoke in the work. This is part of, if you wish, a narrative, but then there's the other part of the labor, which is organizing the materials, thinking about composition, etcetera. I think, in that sense, there are some similarities in our work in accessing the past, accessing ancestors, and accessing memories, and then manifesting the work and giving it flesh, I think both of our works have bodily qualities.

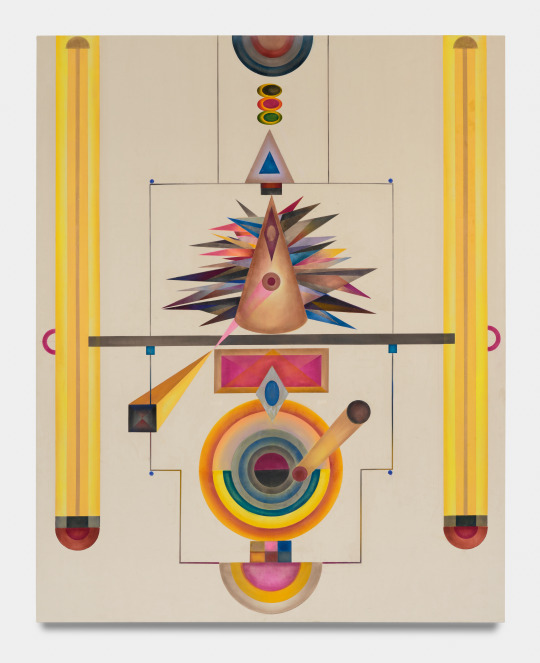

KKW: Yeah, definitely. I think that these aspects around physicality have become more prevalent in this most recent series of works because I’m really studying and thinking about heraldry in relation to my work. There’s this quote–

MP: What does “heraldry” mean?

KKW: So heraldry as in coats of arms and such.

MP: Right!

KKW: There's pretty much like this language and system of metals, colors and materials; different visual motifs that denote a family’s identity or an individual’s relationship to their family. There are select offices where people study the previous millennia’s heraldic markings and work to ensure that tradition persists into the future. One of these titles in Scotland is known as the Lord Lyon King of Arms and he and his staff have records of every coat of arms ever appointed and oversee the creation of new arms because though arms could be inherited, between marriages and descendants, the markings of a family could go through any number of alterations–there are evolutions to it. One of these Lord Lyons said that heraldry is “the handmaiden of history” and I’ve been fixated on it since.

Even before knowing of the quote, I had always seen these dishes as my family heritage, there’s so much power and presence in the dishes. My family started immigrating here in ‘93 and brought every dish that I, having been born in ‘95, grew up on. Each of those dishes is incredibly formative in molding this concept of who Kemar is. Those dishes are markers and coats of arms for my family, serving as a way to evoke an aspect of our relationship to one another. So I’ve been leaning into that system recently, in the shape of the surfaces and the sort of–

MP: Some kind of new symmetries are happening.

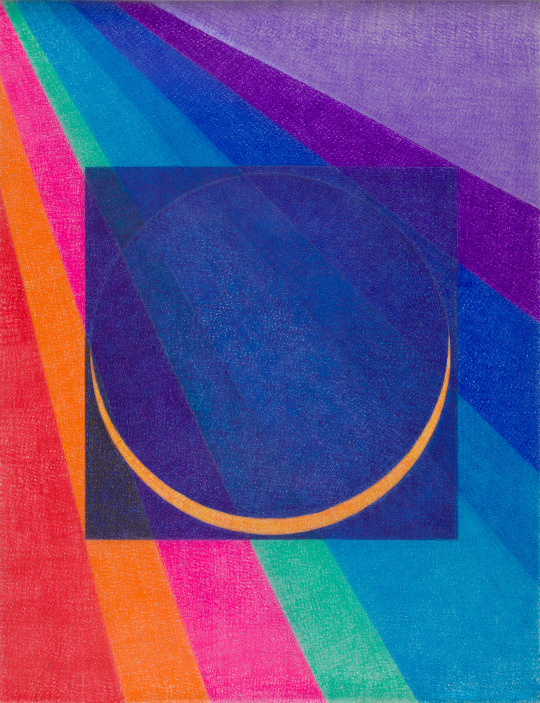

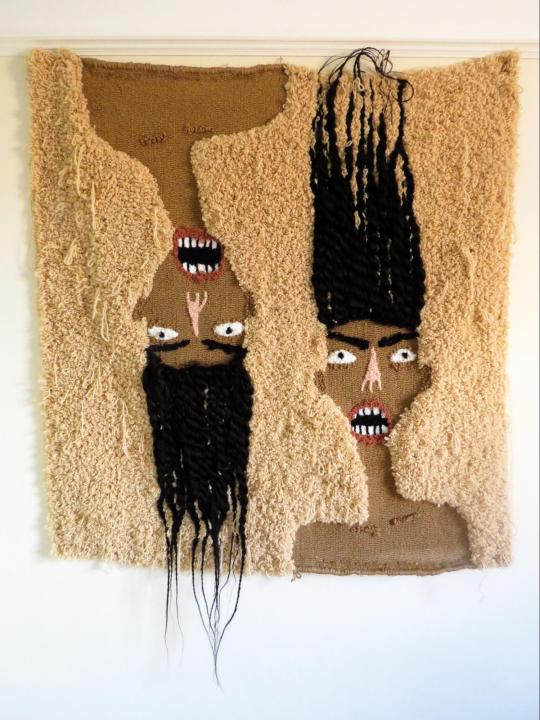

Kemar Keanu Wynter, (VI.) Tomorrow’s Dumplings, 2022, Oil pastel, acrylic, graphite and grommets on collaged French cardstock, 52.25 x 48.625 inches

KKW: Yeah, so the new works are all hexagonal because I'm thinking about shields, and I'm also thinking about Tupperware for holding food. You know, the painting is a container, so why don't I literally create the surfaces such that they evoke their relationship to the container, right? So for me, the hexagon made natural sense in that regard and with regards to that sort of triangulation that you're referring to, there are ways of partitioning shields, breaking their fields to identify your allegiances. The partition I'm using throughout these paintings is the saltire partition, which is utilized by the flags of only a handful of sovereign nations. The one’s I know off the top of my head are the United Kingdom, and more specifically Scotland, Grenada, Burundi and Jamaica so it felt like it made so much sense to take that form and keep it as my reference to Jamaica. Especially when you consider that this assumption of heraldry also runs headlong into a tradition intermingled with many fraught centuries of British hegemony.

It's been interesting for me to have to work with the complication of the per saltire partition across like a hexagonal form right. So now this hexagon is broken into these four fields, two rhombuses, two triangles and now I have to figure out how to deal with the composition.

MP: You in fact have partitions, where before you used to have fields, right? your surface used to be a field where you went swimming and now you have these partitions, these are boundaries. I imagine that you want unity at the end of the day but the idea of boundaries is also everywhere. Did you impose them on yourself, or did you think they were necessary? These demarcations also seem like they want something from you too.

KKW: Absolutely, they definitely give me something to sort of wrestle with and instead of there being one field, like you were saying, now there's four and how do I reconcile all of the sort of happenings within each of these fields? How can I make each of the fields function strongly, independently and then also operate together as one unit, one heraldic structure that also embodies the dish that catalyzed its making.

MP: Are you facing challenges related to entering a more mental space with the addition of these physical boundaries? I notice variations in the time-marking marks interacting with the divisions. Are these changes worrisome or exciting?

KKW: It doesn't entirely. I'm always open to making new changes in the work but the thing is, if I'm going to make a change in the work, it's something that I've probably been deliberating over for months before I actually make that first move. But once I do, I'm fully committed to it and to seeing it through to some point of resolution. So making the hexagons felt very natural, I'm really just taking a square and just tapering it at some of the edges, that was easy enough.

MP: I like the triangle because it's a very stable shape. Very solid, and present.

KKW: Exactly. There’s definitely a certain oomph to it for sure. There's that aspect of it of like having that sort of shapeliness, but the thing that I wrestled with the most there's now this sort of question of how I'm handling the surface because in prior work, I was sort of doing this sort of all over gestural mark that involved a lot of smearing and created a fairly uniform surface. Now, I’m also building more densely layered areas over that. I've done each of those approaches independently in work, but I'd never brought them together until this point. So it was a thing of just like, really wrestling with surface quality, and like really wrestling with how the sort of finished work should look.

And I think having those partitions to like really designate spaces for those sort of those textural qualities to exist, sort of in their own spaces, but also as part of the whole was the thing that made the most sense. I've always been like a very regimented, very list-oriented, a person who really benefits from having things very clearly delineated, so having those boundaries felt really natural and felt very generative in terms of just like really just figuring out the peculiarities of these new works.

MP: Coherence also with your way of thinking, organizing your brain, and also finding a form or shapes that make a mental click.

KKW: There's this moment where everything sort of just seemingly fits together. I'll build up the surface and have a first draft of the work, but as I'm looking at each section relative to the ones around them, I have to go back and respond according to what's going on in the other fields. So it becomes this call and response and I have these four parties demanding different things from their neighbors.

MP: There’s some kindredness; taking a bit of the DNA from this one, the DNA from that one. I saw a picture from the residency upstate where the paintings were all on a wall, and I could feel my eyes jumping from piece to piece, and my brain acknowledging the familiarity and sensing that the pieces required some democratic attention.

KKW: There's definitely moments where there's parts of the painting where I'm like, I love this section of the painting, but the whole painting falls apart because of it, right? And so I have to sacrifice that section and it becomes something else, for the sake of the cohesion of the whole. There's some times where sections pop, but it works because some of the other areas are a bit more muted or uniform. So there are those moments of calm within the composition that allow for like other places to speak more loudly.

The paintings now really feel like cooking, these are the most cooking-esque paintings that I've made. It's just like working on a stew for hours and like realizing okay, I need to add more of this seasoning here, and as things reduce down and tenderize and break down the flavors change again I realize, okay, I need to actually introduce a whole ‘nother element to round things back out.

MP: Is there one particular dish that requires all your attention, or you are talking about having different fires, controlling the temperature on all of them and making sure that nothing is burning?

KKW: You’ve got to maintain the tempo. I use stews as a general reference point to talk about the paintings, but I'm handling multiple burners at once, moving back and forth between the surfaces. If I hit a soft wall, I’ll move over to another one on the other side of the studio, and work on that one for a little while, just getting a little visual rest from the painting to return with fresh eyes and a new perspective. Or I'll make a mark on the surface that I'm currently working on right and graft it over to the one that I'm struggling with and it fully recalibrates the composition. It's become a really good sort of give and take, figuring out how not to overdo it– getting the tastes right, getting everything to harmonize in the right way, not necessarily having them all operating at the same level but having everything make sense by the end of it. Like having really sour notes but then having some sweet, some bitter and a hint of char to make it make sense. So it's not just a dichotomy at play in terms of balance, it’s numerous sensations operating in tandem.

MP:

I think that that's something I need to do more in the studio, I get lost in one single piece. I get completely devoted to one single surface, but I have this innate trust that there's going to be a common language across all of them. But there are moments where I'm like, wait a second!, and I crave a little bit of what you're having right now; this contained energy with these groups of work, that they help each other and feel like more of a community of objects. In my studio right here, I sometimes desire that kind of consistency.

KKW: I see the works that are around us right now and feel like there is definitely a familiarity amongst them, like they all know one another. There are nuances to the way that the surfaces are applied of course, but within that there are common through-lines between all of them. It’s most notable in the way the works reach away from the wall, out into space and towards the viewer. Even with the bindings, the yarns that weave around and serve to dictate the forms. A real kinship exists, they all branch from a central bloodline.

MP: I hope so, I think as an artist, that's what you hope that you make your choices, that this knowledge and interest is so deep, that it is going to be integrated into your system, that your psyche and your body are taking care of that process. And you can just do the work because you absolutely believe in it. Then it becomes about the materials you choose to do the right thing on the surface. We both work with surfaces, right, I think we both want some acknowledgment of that surface, we like touch. How did you arrive at that?

KKW: I've also been sort of wrestling with that question of like, what is true or what is honest? Because I really want to make honest paintings and I think that in the last year, what I really have come to realize is, I find honesty in that point of my practice where I let go and remember that I've been doing this work and that I know what I want in a painting already and what’s been accumulated.

MP: I agree with the wisdom of the body.

KKW: We've accumulated knowledge that’s gotten coded into our muscles, what marks feel good to the hands, wrists, the body and how to make them. That also extends to our materials, we know what makes sense and resonates. We’ve developed this knowledge over years of investigating within the work and to a degree there are moments when we don’t need to think about what we’re making and just let the body do. There are times where I find the most interesting passages in my work happen in those moments when I’ve receded into the background, into the music playing in my earbuds, and just feel it out. That might be five minutes or two hours but when I come back, I find that I’m in a location beyond the hump or complication that I was brushing up against and that intuition was able to serve as the guide in the moment. It’s true because it didn’t have to be forced.

MP: Right.

KKW: Not that powering through and pushing through a painting doesn't have its benefits in certain moments, but letting go of the preconceived painting in my head and letting all of the body wisdom that has accumulated– that understanding of color, that understanding of mark do what it needs to do and take control of that moment and get you through that ravine of uncertainty to that other side. If that makes sense?

MP: That makes sense. I feel that also-correct me if I'm wrong, but I feel something kind of similar; you make this work, then there is a point where you need to jump! Mostly with each piece, you have to jump and know that you're not going to break your head. It’s the trust that you're going to do the job every single time, and you're going to come out alive after that jump. I think it's a matter of material congruence, with personal histories, personal narratives, and with context, but also trusting the walk to the edge. I don't know how you feel about that. People work in different ways. I like walking on the edge with performance in particular, but also with the object-based works here, and I like to believe that I'm going to come out alive after that experience. It feels like you are surrendering yourself to life in each piece - I don't know, maybe I'm exaggerating! But I feel this gravity every single time I perform. Since the performances are absolutely related to the work, then it helps me know that I'm taking the right risks and that if I'm afraid it’s OK - that's my main barometer. You have to have a little bit of fear. Sometimes I've had a lot, and it's unsustainable, for me, Mónica, sensing that fear can be a very good indicator that I'm alive, and I'm taking risks.

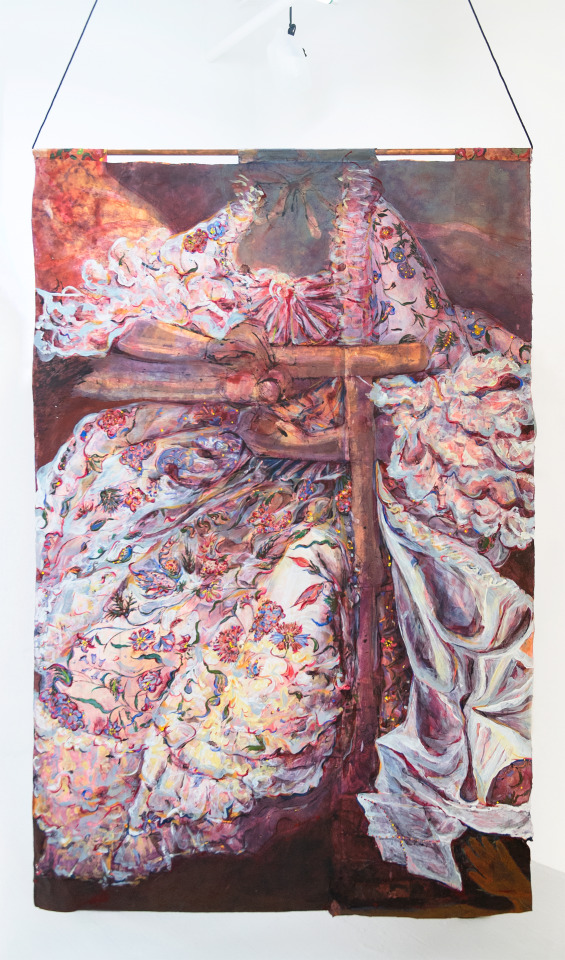

Mónica Palma, Before I Started Working With My Mouth (performance), Plexiglass panels, activated charcoal, honey, aloe, saliba, microphone and amplifier, 2020

KKW: Do you ever think that the embrace of fear and push on your boundaries that happens within performance expands the sort of boundaries that you have within the walls of the studio when you're working? Or do you think about performance and your painting practices sort of independent of one another?

MP: I find them completely related, but perhaps that's up to the viewer. My desire is that they are seen as related, if not even different manifestations of a single idea. In performance I expose my body and my body becomes a surface. I'm starting to see more and more that the pieces here in the studios are bodies that I act upon, and though not precisely my body (because it’s external), they feel like a proxy for my body. So for example; those marks on that piece are bites that are framing the metal. The last performance that I did in Tennessee I was using twine braids to tie up and restrain my body. In some of these pieces I'm also using braids to transform, mold, and mark the surface. And many of the pieces were done in a very performative way, more like private performances. Someone asked me if I ever film them or take pictures while I'm doing that, but because I'm so busy with my body, hands and mouth I never did.

KKW: I feel like there's this interesting relationship to like, to intimacy that exists within your work that I’m fascinated by. With the bindings I'm thinking about rope bondage and how aspects of power and control exist within that work, but simultaneously functions as an artistic practice where you're also using the rope to accentuate and sort of exaggerate the dimensions of the body. For me, it's interesting to think about these surfaces as surrogates for the action. These surfaces are your participants in these assumptions and relinquishments of control. As artists we're always sort of engaged in that because like we were saying earlier, there's that point where the work also tells you what it needs.

MP: I'm thinking about your small drawing pieces where you see your fingers smearing the oil pastel. I had this thought that you were tapping into S&M dynamics, although I'm not an expert in it, I'm interested in the idea of domination and pain, the kind that makes you feel present. I have a medical history, where too many things were done to my body, in a moment, at an age, where I could do nothing (I was 12), I had to be there for doctors to do things to me, to cut, to put things in me, and to extract things. The older I get and the more experience I have, these themes continue to emerge: themes of acknowledgment of a body and making it present.

I started using the braids thinking about my Mixtec grandmother's hair, and then braiding and wanting to bring that very simple action of transforming hair into my pieces, then eventually I wanted that braiding to be a force too. Those kinds of actions and materials are perhaps similar to the way that food is for you. They feel right. Like if someone doesn't get it, it's OK. I believe in the actions. It feels purifying. It feels liberating.

Mónica Palma, Cae mi voz (Mi voice is falling) performance, Chair, mug, hand dye braid twine with cochinilla, amplifier, microphone, vinyl text on windows, and serigraphy paper posters with poem by Xavier Villaurrutia, 2022

KKW: It is also interesting with braiding because you know, be it hair or any other fiber, that act of braiding strengthens the material. Even in this moment of vulnerability there is also this reinforcement that is happening. I think about that in relation to your works with these metallic edging, the central fields are paper but then they have this structure that once again, sets the boundaries, but those edges have this sort of strength to them, this rigidity that transcends the paper. It becomes like armor. Let me know if that doesn’t sound right.

MP: I think it's definitely the case with the metal that I've been using. They have the strength of bones. Those pieces you mention were done using the doors of subway cars. I took them on rides and I crushed them between the doors, and I enjoyed the moment where the middle of the doors and the rubber touch each other: metal meeting metal, that union, and the force, an external force that is the doors of the cars, marking the drawing. It was quite performative, even though I was not fully the one doing it but the machine. I'm not fully participating but I'm orchestrating the crushing.

KKW: You're a sort of conductor, you're setting a score. I would never say that I’m the most well versed in happenings but I think about how the Fluxus folks often had set instructions and parameters in place for the execution of their performances. I think about the medical situation in your past where you weren’t able to have that power in contrast to your role as the conductor in the subway and how there is a power in that relinquishment. Where you’re able to establish these parameters that are slightly out of your control and can exist outside of your intervention.

MP: I like what you're saying - I think it's about asserting the presence of the body. I'm talking a lot about my body, it is also about making visible the bodies of others that are not being considered, and asserting a presence by bringing materials to the front, by bringing the wound into view.

KKW: Making those who are pushed to the margins, those who are often invisibilized more visible in a way?

MP: The work gets political. Absolutely. Sometimes it is more explicit in the performance, the work here in the studio feels more abstract. Through the use of loaded materials like volcanic rock - of the same kind that the Aztecs built their pyramids which the conquistadors destroyed and used the same rocks to build their churches– materials like this bring the political component more to the fore.

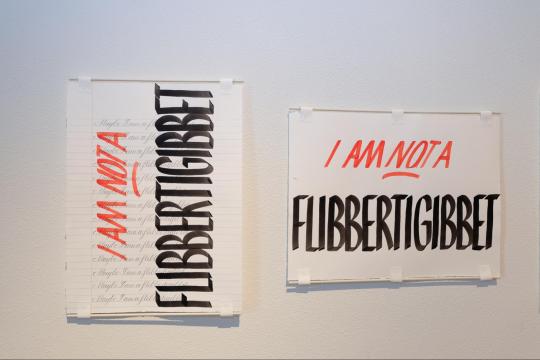

KKW: How do you feel about that? It's something I always think about. That idea of legibility as someone working within abstraction. Prior to this, you know I was working with coded text, creating these conditions to obfuscate and slow the read of the writing I was sharing. And it's been interesting because as I’ve been making these works, I've realized that the coding is no longer important to the work and frankly, it was funny to look back because I realized my efforts to obfuscate the work, still ended up centering the white gaze in some ways. And so it's been interesting just making the work now, just now I'm just sharing the writing.

MP: More straightforward.

Mónica Palma, Ribes and Bites, Aluminum sheet, calligraphic rice paper, glue, encaustic and braided rope, 38 x 27 x 13 inches

KKW: Yeah just straightforward, leaving it for people to read. I find so much, there's a sort of freedom that comes with that I think, that I didn't notice, or that I didn't realize was absent. That like there was a sort of pigeonholing that I was setting for myself in this effort to speak on the hyperconsumption of Black cultural production.

MP: What you are saying right now is very important: the realization of who are you serving, right? Who are you? Who's the viewer? What do you make work for? With what energy do you make the work? It's interesting because I think both of us have very personal stories to tell about our work, yet we are abstract artists. And for me, I don't know if you feel like this, but it excites me, and I definitely want to go back to what you were saying, because I think it maybe gets to the core of this conversation. I find so much of your practice in the world of sensuality and materials. And I feel that that is revolutionary in a way to claim– to claim the flesh, to claim the dirt, to claim the body, to claim the surface, to embrace the smells. I want to be in that world. And I have other things to say, they're incredibly important to me, like credos. I absolutely need them, but I want the work to have this form manifested in the world in this way that is abstract. Because it's the most sensuous form that I know. And it's not prescriptive.

So back to what you were saying, it sounds very important, that moment where you became more assertive and decided to remove the text.

KKW: Yeah, I definitely feel like taking out, shifting that element of the work has definitely been a way for the work to be more honest. To push the work further toward this idea of truth or honesty. At the end of the day, I’m making the work first and foremost for Black folks, immigrants, folks of color. Reaching out to those who have their own stories and identity woven around these or their own culturally essential dishes… and I find greater pleasure in the work now.

MP: It's so interesting, because it's not indulgent, it's pleasure. And there's a difference between indulgence and pleasure.

KKW: I feel like the joy is purer, now that I'm not thinking about this additional realm of labor that I’d been imposing on myself, to then place within the context of the exhibition or simply engaging with the work.

MP: It’s very hopeful: the path to ownership, to have ownership of your own story, and your own pleasure too. Is there something you would like to ask me or to ask yourself?

KKW: I feel like discussing more in regards to truth and honesty. I feel like we’ve spent a lot of time talking about my thoughts and I’d like to hear more about you.

MP: I will talk more about congruence than honesty. I like the idea of congruence because I feel that it speaks of a convergence of different places falling into the right place, into the right spot. For me it’s related to a search for materials; I put a lot of eggs in that basket. I tried to extract these ingredients and information and make them meet. I want to see if these particles, these elements, when they come together, if there's some kind of amalgamation, but where they can also keep their individual identities shining. Also, I can act upon them and they can allow me to participate, they can allow me to enter. It's an invitation for different elements to come all together. But I don't know if I'm doing any justice to the question of honesty, which feels huge.

I was listening to some writers talking about honesty—fiction writers—they were saying how honesty has nothing to do with the labor of writing fiction—that kind of truth is somehow irrelevant, because you're talking about building different worlds—constructing, characters… Of course you have to have integrity, you have to have some order. But framing the work in terms of truth and honesty was mostly irrelevant. It's not that I see my work as fiction, but I can say that I love written fiction, and it’s almost the only thing I read. I wonder if there might be some similarity between fiction and abstraction, in the sense that what I'm presenting here is not volcanic rock. What I'm presenting here is not me. I'm making these amalgamas—I don't know the word in English—amalgamations! They're creating a third something. So the elements might get a little corrupted on the way, because they traveled from Mexico to here, or even in the thinking because they get transformed by so many factors, including the infidelity of memory. I don't know exactly if what I'm making is really a matter of truth, so much as belief. I feel like there's an element of fantasy to it. But I think that in any fantasy there's some kernel of truth. It’s tricky to make sense of. What do you think—can you help me with this?

KKW: How you think about it is also how I think about it as well. I think that when it comes to honesty there is a lot of room for slippage and for things to not necessarily be exactly how they occurred in history. Because I think about a lot of these pieces that I've written, looking back and reading some of the things, I know this isn’t exactly how it happened, but this is how I remember it. That's the thing, memory especially is such a subjective, such an easily tarnished thing. I've decided that there's no point in fighting it. Whatever your brain is able to evoke that's the honesty and in some ways, I think that as artists we are maybe in some ways unreliable narrators but at the same time, because it's our story to tell we're the most reliable narrator you’ll ever get.

MP: I like what you're saying. I think it's almost like you believe in the grey area. I think we're believers in the grey area.

KKW: Yeah, we're always floating through the fog a little bit.

MP: And if I asked you about your auntie in particular; the order of her cooking ingredients, you are the holder of that information, there's veracity in that. But I think allowing yourself as an artist to explore and take those grey areas, that spacing between buildings, you know, that little gap, the alley or where the dust is being accumulated. So that's sometimes where the juices are there's an area that hasn't been completely defined.

KKW: There are times where I've written about dishes and most of the text isn't about the dish itself. I wrote something recently about a meal I had in Europe and the majority of the vignette is about the day that I had after the meal. It was just like talking about the weather on this particular afternoon and how the air felt on my skin, strolling along a canal for hours doing nothing in particular and in my mind, that's as much about the dish as like the actual talking about it directly. We have this luxury of being able to frame the image exactly how we want to present it.

MP: So if there's some sort of veracity that veracity for me is in being in front of the object—in the composition, in temperature, the visual temperature, in the touch—that's the veracity. The rest of it goes somewhere else, beyond. Maybe it has to do with dreams, maybe with memories, and we know that the concept of memories is complicated, like false memories, for example; the more you think about something, the more you transform it in your brain. But as visual artists we need to go back, back to having a bite of that food right? We travel back to that tangible moment or memory.

I wanted to ask you about—this is a bit of a jump to something different—but I know that maya, your partner, was with you at their residency. How was that? Are they involved in your process or a particular kind of viewer? What's their participation in the work? How do they see it? Do they give you feedback?

KKW: It’s interesting because I would say, it's usually one or two things when it comes to relating to the work. It's usually either they'll come into the studio unannounced and see one or two things that really draws their attention and that's usually a good sign I'm in a good place because they're one of the best color theorists I know.

MP: Wow. And they’re a writer.

KKW: Yes, they're also an excellent writer, so I trust them heavily. I trust them fully when they say something is exciting, I usually try and coax as much information out of them as possible about why they find certain aspects intriguing. I’ll usually take a line or two of notes and keep that percolating in the background as something I should be mindful of while working.

Alternately, there are times where I instead ask for feedback. I’m very much a studio hermit and don’t like having people interfering with my work especially when I’m actively in the midst of a session. I need to be in my mind with minimal distractions while working, when I reach around 85–90 percent done with my work, that’s when I might actually call maya in for some feedback and a temperature check on things happening on the walls.

MP: Going back a little bit, tapping on the theme of truth and veracity; Isn't it a beautiful thing that, when you love someone and you respect someone in your life, that person can see you and you believe them? I mean, when Calvin, my husband, says something about my work, I actively listen, though of course occasionally I disagree. The amount of trust that you can build with a partner who's in the arts or even if they are not but they are sensitive and receptive. It's really beautiful.

KKW: It’s definitely surreal, the sort of sensitivities that you have with the people that you care for and their work pulls a different type of critical energy that I think is– it's not necessarily meant to be people pleasing. This is where I stand in relation to your work. With an awareness of your tastes, but also an awareness of their own tastes, seeing those connections firing behind someone's eyes while looking at your work is a beautiful thing to watch.

MP: Sometimes it's the awareness of how they perceive you. Sometimes they see that you've been losing your mind in a project. They sense your energy, your mental health, "That thing is destroying you. Chill!"

KKW: Exactly. Oh my god, very relatable. It’s vital to have that outside look.

MP: Those kinds of viewers are so valuable. I don't know how many you have… well it's not about the numbers. It's just so important to have at least one person like that, who is going to give it to you straight.

KKW: Absolutely. Funny enough, I actually trust my family a lot. None of my families are necessarily like formal artists, but I trust them when it comes to their thoughts regarding my work because the thing is, all of these dishes are based on familial gathering and dishes that we've all eaten, often together. If I tell them the title of a dish, they immediately start laying out all of their own relationships to the meal and ideas about the painting. Frankly, they're my first audience, right? Back when I was in school, I always said that I wanted to make paintings that my mother would like, so you know.

Kemar Keanu Wynter, (V.) Earl Grey and Water Crackers, 2022, Oil pastel, acrylic, graphite and grommets on collaged French cardstock, 48.625 x 47.25 inches

MP: These folks have a sensitivity that is very similar to yours. I mean, they might not have a studio, but they smelled the same ingredients as you did. They are anchored in a sensuous world where, adding the salt, they know that in order to make a dish some steps have to be followed. It's almost like synesthesia, you know, that they can taste and get where you're going after.

KKW: Exactly, there's an equidistance between us and these reference points. It’s easier to make connections from work to dish and of course we share a lot of these memories.

MP: It's all under one umbrella.

KKW: Exactly. It’s all woven together. Also, I think there is a bias that also comes from me not having a formal, dedicated studio in New York. I’ve sublet one here or there for a month at a time but that's it, so I don’t really have a lot of visitors. There’s a few family members who are usually actively up to speed about what I’m working on, maya, a handful of other individuals and yourself, with us having so much kinship between our practices. I know you’d get what I’m working out.

MP: I have been in your studio. Yeah, remember when you were at the Ortega (Ortega and Gasset Projects), I saw those paper pieces.

KKW: The collage pieces.

MP: Were very interesting. Fascinating.

KKW: Those works have definitely led me down the path that I’m on now.

MP: I still see traces of that work they were also coming from tracing I guess, food containers?

KKW: I was pulling from the forms of actual food, drawing them over and over and abstracting them. That was January of 2018, so five years ago.

MP: You first came to my studio sometime later. And then you also saw me perform on the street.

KKW: Yeah! We’ve been in long range communications.

MP: Right. I agree with that. Yes. Are you still mostly using oil pastels?

KKW: Yeah, mostly oil pastel. I remember that you said the marks you’re making are produced from a sponge right?

Mónica Palma, Big volcán, Aluminum sheet, calligraphic rice paper, glue and encaustic medium, pulverized volcanic rock (tezontle) and braided twine, 2022

MP: Yes, though I also use brushes. These surfaces are now sheets of metal (aluminum), which I coat with layers of rice paper, dipped in archival glue. They make some kind of armor or exoskeleton that I can manipulate. Sometimes I bite them or spoon with them. And recently I started using encaustic to draw on them. Most of the work you’re seeing right now is encaustic, but I sometimes mix it with ground volcanic rock. And here is where I “cook” my ingredients. I've really been enjoying the heat source. I enjoy having to kind of control it, turn the heat down a little bit, also the immediacy I have to react first right at the moment.

KKW: It becomes the heart of the studio. It's so interesting how certain tools can just sort of shift the gravity of the space, you know?

MP: Right. It's like in a home people tend to gravitate towards certain areas like a kitchen. Wait, did you move away from the grommets?

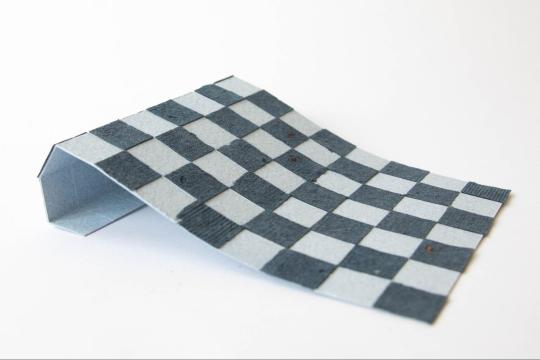

KKW: Oh no, I'm still using the grommet. The grommets are an element of the work that just like will never leave. It's one of those elements that entered the work out of necessity.

It came out of the desire to make larger surfaces and using small sheets of paper to make that happen. It's one of those things where I don't ever see that changing because I think that I kind of like the compactness of just having a stack of paper and those same sheets often become drawings. The utility that comes from being able to take an element or ingredient and utilize it, modify it repeatedly for various functions, and various suites of work just feels right to me.

MP: It feels honest, right, and looks right too. I think it gives a lot to the viewer: little portals, and binders too. The exposure of this material versus the other one; the oil and metal.

KKW: Everyone always asks if they're metal, and I love saying no. It’s one of my favorite things, I love that sort of illusion.

MP: Wait, they’re not metal??

KKW: No, they're paper. They're all paper.

MP: The grommets too??

KKW: Oh, no, my bad. The grommets are metal, the surfaces primarily are paper.

MP: All my pieces incorporate paper too because I have this drawing-oriented mind. Sometimes, I wonder if I'm just being stubborn. What is it?

KKW: I think of my work as painting through drawing so I get what you’re saying. At this point, I don't even know, right? Where are the boundaries?

MP: Maybe it's not up to us, we have other things to think about.

KKW: Leave it to the art historians to figure it out. Yeah, but it's definitely one of those things where it feels so right to put the grommets in.

MP: Closure and satisfaction! Like punctuation marks after a sentence. Period. Comma, Accent. Parenthesis.

KKW: Absolutely. Also, how would I hang the work otherwise, that's the other question. So as a tool the grommet is serving two vital functions. To borrow your idea of thinking about these works as bodies, it’s like trying to build the body without the skeletal system. At that point, it's kind of just a slouchy mass of tissue.

MP: It's giving it something like an entrance.

KKW: With how many grommets go into our surfaces, it actually does make them more rigid in a way

MP: It must be so nice feeling the weight when it's just paper, and then after the grommets come, sensing the weight.

KKW: You're probably the first person that ever really brought that up without me mentioning it. The way the paper changes from just being this fragile thing to something truly robust.

MP: Savoring the weight! Today, I got some X-rays, and they put the weighted blanket on me and now I'm almost having that sensation. They have a substance.

KKW: They're substantive but they're also kind of delicate. If they’re handled the right way you can really maximize the robust traits of the work rather than emphasizing the sensitivities

MP: I think there's something similar also with my work. They have a fragile facade. Especially these days (with the combination of metal and paper) people don't know how they were made. It's not that I'm intentionally trying to trick anyone. It's just doing what feels right for me.

KKW: Thinking about the work and its relationship to people. It makes sense that there's a certain level of trepidation, a certain level of sensitivity to the way that the work is hung or sits on a wall and exists in space, so that you’re not compromising or endangering the work because they have a certain solidity.

Mónica Palma, Small volcán, Aluminum sheet, calligraphic rice paper, glue and encaustic medium, pulverized volcanic rock (tezontle) and achiote seed powder, 21 x 22 x 8 inches, 2022

MP: In my case the work has been already intentionally injured or intentionally touched. I think they are already accepting of their not being imperfect. But yes, when you hold them, you realize that they need some care, but they also are allowed some level of roughness too. Just by touching, the pieces tell you what they need.

KKW: Absolutely, I'm always sort of relearning my sort of engagement with my materials. I’m figuring out new ways to pack them, new ways to build up the surfaces like there's always something that's changing. Previously, I was using rags or the side of my hand to do a lot of the smearing but I've switched over to gloves and the way that marks are built up is completely different.

MP: Totally.

KKW: There's a slickness to the touch that changes things which, and for the most part have been for the better, but then I've noticed other moments where like, Okay, I need to, like, shift the approach a little bit, right. Yeah. And, yeah, it's good. It's like it's, it's kind of like dealing with people. I mean, I'd like to think that the paintings have a sort of vibrancy and a sort of life to them that you know, they have presence.

MP: Something kind of anthropomorphic

KKW: And even beyond anthropomorphic, they don’t even need to be of the body. With the hexagon, it’s hard for me to not think about the torso, or even thinking about shields and how they relate to the body of course. But I hope that there’s this element in the work, just in how the surfaces are handled, that these marks are imbued with enough care and intention and intimacy that vestiges of myself can be felt and radiate off when you’re in the presence of the work.

Mónica Palma was born and raised in Mexico City and studied visual art at the Universidad Veracruzana in Xalapa, Veracruz. She received her MFA in Painting and Printmaking at Virginia Commonwealth University. She currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Her work has been shown at TSA (NYC), 245 Varet Street (NYC), Ortega y Gasset Projects (NYC), the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City), Soloway Gallery (NYC), Underdonk Gallery (NYC), and Essex Flowers (NYC). Since 2020 Mónica has been a lecturer at SUNY Purchase in the department of Painting and Drawing. In 2022 she was the AIR resident at UTK in Knoxville TN.

www.monicapalma.com @mopanana

Kemar Keanu Wynter (b. Brooklyn, NY) holds a BFA from the SUNY Purchase School of Art and Design. His work was the focus of recent solo exhibitions at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York (2021) and Tiger Strikes Asteroid, Queens (2021). He has exhibited in several recent group shows including Notes on Ecstatic Unity, OTP Gallery, Copenhagen, Denmark, Faraway Nearby, North Loop Gallery, Williamstown, MA, and Shining in the Low Tide, Unclebrother, Hancock, NY. Wynter has been an artist-in-residence at The Macedonia Institute, Anderson Ranch Arts Center, Ox-Bow School of Art, the ARoS Kunstmuseum in Aarhus, Denmark and AQB in Budapest, Hungary (both facilitated by Flux Factory, New York). His work is held in the collection of the Art Galleries at Black Studies at the University of Texas, Austin. Wynter has forthcoming solo shows with Encounter Lisbon and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery in the spring of 2023.

cowfoot.studio @cowfootsoup

0 notes

Text

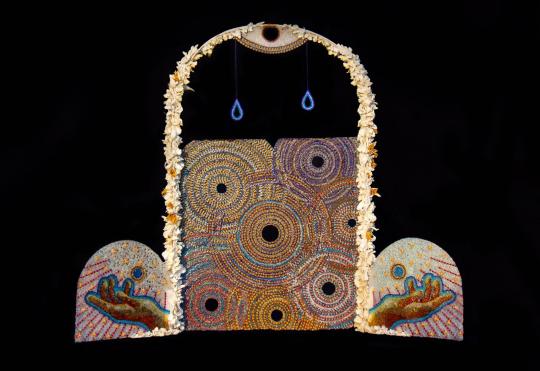

29. Dana Davenport & LaRissa Rogers

Dana Davenport and LaRissa Rogers discuss their experiences as Black and Korean artists and how their research and life experiences have led them to work with specific materials, motifs, and ideas. They discuss their work through the framework of family history, belonging, and Black-Asian futurity/solidarity.

Dana Davenport (DD): Hi LaRissa! I'm so excited to chat with you about our practices, expressions of identity, and interconnected histories. I came across your work a few months back while doom scrolling on Instagram. Unlike most days, I can say it was productive as it brought me to your work. I was thrilled to come across another Black and Korean artist working within similar mediums (sculpture, performance, and video). I was equally as excited simply to meet another Black and Korean person. I asked our mutual friend, TJ, to introduce us and now here we are. As I began to dive deeper into your work, I discovered so many throughlines in how you utilize the body, draw from familial history, and use specific materials to dissect identity. Perhaps, as a place to start off, can you talk a bit about your relationship to the materials that you're currently working with?

LaRissa Rogers (LR): Hi Dana! I am very excited you extended the opportunity for this correspondence. Similarly, I found your work doomscrolling on Instagram a few years back, and I was immediately a fan. It was exciting to see someone working through their identity, familial history, and materiality as a Black and Korean femme. Then a few years later, I received a lovely email from TJ, mentioning you were in LA and introduced us! It was such a great surprise, and I am so excited to start this relationship and pick your brain! Haha.

For me, material history is the easiest way to dissect and draw parallels to identity formation and larger narratives around diaspora, migration, belonging, violence, labor, care, etc... At the moment, I am working with porcelain, sugar, and soil. I began working with soil in 2019, almost as a default. I had just finished a project, “We’ve Always Been Here, Like Hydrogen, Like Oxygen,” which was a performance on the Richmond slave trail. The performance consisted of me washing my body with oranges as a ritual of self-care. At the time, the BLM uprisings were happening, Breonna Taylor was assassinated, AAPI hate was high, and I was paralyzed by the similarities in the political landscape of LA in 1992 and the current times. For me, oranges were a direct link to the Latasha Harlins murder and the erasure/silencing of Black women and girls. But, this case is very layered and complex. It's about anti-blackness, fear of others, misinterpretation, the legacy of slavery and policing, the corrupt judicial system..and I could go on. But, essentially, we have to look at this event holistically and consider all of the ways internal and external anti-blackness showed itself in violent ways. I wanted to use the Richmond slave trail and the African burial grounds to think through how we are implicated through landscape and history. It was also important for me to link temporalities and draw out similarities between these three moments in time. This performance was an outcry, an attempt at asking: “what does it mean for Black women and girls to be protected and cared for?” The title of the piece stems from a Dionne Brand quote, when the descendants of enslaved people meet their ancestors in a slave castle – where the ancestors say in awe: “you are still alive, like hydrogen, like oxygen.”

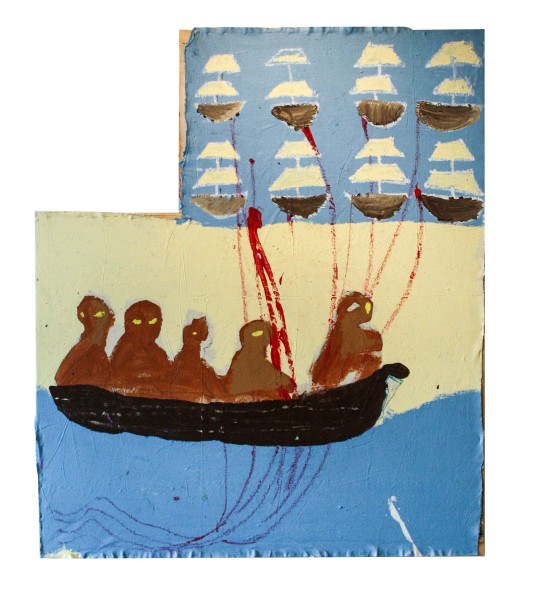

LaRissa Rogers, We've Always Been Here, Like Hydrogen, Like Oxygen, 2020. Double channel video Installation, 7min 22sec. Installed at Resurrection Lutheran Church, Richmond, VA.In Light 2020: Safety and Accountability. Photo Courtesy of 1708 Gallery. Photo by David Hale.

LR: This work leads me to work with soil. I was in online grad school at the time and had just moved back to Virginia (where I was born and raised) and did not have a studio. So, naturally, the landscape became that for me. As we already know, Virginia is a fraught place. I lived in Richmond for several years while attending undergraduate school and stayed a bit after. But, I was born and raised in Charlottesville, VA. Reading the news one day, I encountered this article about Pen Park. I grew up going to this park when I was young. My mom would take me to play at this park while we waited for my brother to get out of school. My father golfs there as well. But, Pen Park used to be an antebellum plantation. At Pen Park, there is a golf course, and on the golf course, there are unmarked slave graves. This place is not acknowledged. Around this time, I was also thinking heavily about monuments. The confederate monuments in Richmond were getting pulled down, and it seemed like every major city around the world was having conversations about their relevance and relationship to collective memory.

In Christina Sharpe’s In The Wake, On Blackness and Being, she speaks about residence time. She describes the residence of sodium held within the body being 260 million years, in relation to the enslaved Africans who were thrown, jumped, or dumped in the ocean during the middle passage. This residence time allows one to begin to think through the terms in which we understand the conditions of Black suffering. In contrast to water, the body takes approximately 200 years to return to dust when buried in the ground. As the nutrients of the body disintegrate back into the earth, how can thinking through residence time in the soil help us understand what it means for Black people to suffer when suffering is the ground?

Given how closely Black people are indexed to death, soil also holds the capacity to speak to regeneration. Historically, it is a place of Black resilience and possibility through geophagy, slave gardens, revolts, and the migration of African plants and foods to the Americas by way of women smuggling seeds in their hair during the middle passage. Soil is a living archive and speaks to the nonlinear nature of time. Saidiya Hartman’s theory of temporal entanglement questions how we narrate historical time when thinking about the afterlife of slavery. She calls us to examine the intersections where the past, the present, and the future, are not discretely cut off from one another, but rather, we live in the simultaneity of that entanglement. The ephemeral nature in which many traditions, stories, and ways of knowing are preserved in Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities becomes visible in intangible ways due to colonization. Methods of remembering that cannot be held but are protected through and within the people themselves.

Using this as a framework, I did a few projects with soil, Virginia soil, and soil from different locations with historical relevance. You can see my attention to soil in the works “Ode to soil” “A Poetic of Living” and “On Belonging: The Space In Between.” As a material, soil does a lot for me.

LaRissa Rogers, A Poetic of Living, 2021. installation, Dimensions Variable, Soil from Pen Park and Farmington Country Club, Celosia, Fungus, Oxygen, Light, Care. Photos courtesy of Welcome Gallery. Photos taken by Stacey Evans.

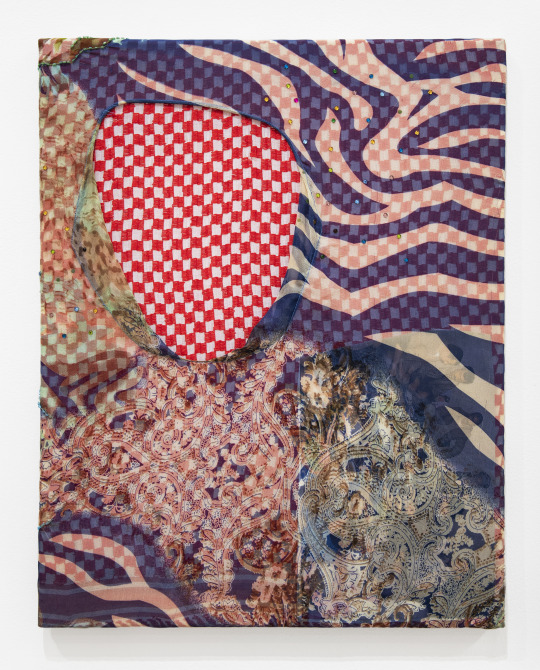

LR: I am also working with porcelain and sugar. I began researching sugar after my project with oranges in 2019. We are all familiar with the sugar trade and its relationship to the transatlantic slave trade in the Americas and Global South. But I am also interested in how sugar functions today within the US context. It disproportionately affects Black and Brown communities – operating similarly to that of the plantation system. My family has a history of diabetes and sugar-related complications. Alternatively and historically, sugar is a commodity that has connected all four continents. The first significant wave of Korean laborers worked in the sugar plantations in Hawaii. There is also an expansive history of coolie workers and indentured servitude related to sugar in the US. In the 18th and 19th centuries, sugar pastillage was used by European royalty to create table displays for admiration, then consumed at the end of the night. The sugar sculptures became a status symbol often, displaying racialized and exoticized images. With the decline in sugar’s value and the impossibility to preserve the sugar sculptures for long stints of time, sugar pastillage was substituted for porcelain. This porcelain is commonly coveted within upper-class white homes as "fine china.”

Right now I am delving deeply into Anne Cheng’s work around ornamentalism. In yellow feminist theory, the Asiatic subject becomes ornament. Whereas in Black feminist theory, the Black body is bare life, these relationships are important to me and start to touch on the complexities of my afro-asian identity and how I experience violence navigating within a world that prioritizes skin. Thinking through these two materials and their relationship to the body, the mouth, the act of hunger, the ornament – become what Anne Cheng describes as the divergence between Black flesh and Yellow ornament. Using the scars from being whipped on Sethe's back in Toni Morrison’s Beloved as an example, Anne Cheng articulated that the flesh that passed through objecthood needs ‘ornament’ to get back to itself.” This is where ornamentation, particularly the chinoiserie pattern I am researching right now becomes a nuanced symbol and not just a decoration. There are moments when the wound needs ornament – we see this a lot in Black material culture through the use of gold, chains,” swag” –but there are also many times when the wound and the ornament cannot be compared.

The chinoiserie pattern, which the blue willow pattern stems from, was something I grew up around. My mom is Korean, born in Seoul. She was a war baby and orphan brought to the US by a Black soldier stationed in Seoul during the Vietnam war. It is crucial to realize the complexity of her story on a macro and micro level. Her story is a byproduct of US imperialism in Korea, GI babies, and the beginning of Korea's large adoption project that set legislation in place to rid the country of “unpure” Koreans. At this time, there was also sanctioned prostitution of Korean women for the American military resulting in a wave of Korean mothers and American fathers, who eventually moved to the US.

For my mom, once brought to the US at age four, her adoption requirements were never fulfilled, so she remains stateless. She was raised by my grandfather's mother in a poor Black household in Madison, VA. My father, a Black man, was similarly raised in a very poor neighborhood in Newport News, VA. Growing up, my mom decorated the house in this blue and white greenware. I was unaware of the history of blue and white greenware or chinoiserie, but I was always curious about this decision. I read it as a representation of a heritage or place (Korea) that she no longer had access to. My new body of work delves into this pattern, chinoiserie -- a pattern adopted by the Europeans as an idyllic and exoticized interpretation of Asian people and life. I am interested in its relationship to diasporic distance, belonging, and everyday violence that upholds white supremacy. I am also interested in this conversation surrounding the influences, perceptions, and interpretations one performs in the creation of self. The way this pattern, a distant interpretation, a fantasy of others, became removed from its violent history within the home, assumed, and merged with a Black interior aesthetic to create a new language – one that exists in the in-between, the liminal.

For me, the liminal is parallel to notions of authenticity when working with this pattern and being mixed-raced. One should always question their perceptions of purity and outside influences of authenticity. Where does culture begin? With the start of global trade in the 18th century and the rise of capitalism — cultural symbols and objects were constantly being assumed, consumed, merged, adopted, and recontextualized. It’s a violent process. But, in specific situations, this cannibalization or hybrid transformation impacts intersecting identities and allows the violent collision to become something greater than just the violence—especially for those who have been exiled. Edward Glisssant calls this “opacity” – or a lack of transparency for and toward the other– that can “coexist and converge weaving fabrics.” He states that “To understand this truly, one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of the components.” For me, opacity has become a strategy for engaging cultural multiplicity and diasporic imagery of resistance and power. Opacity allows you to be fully seen without being owned. It allows you to occupy spaces you may not be seen as a member of. Opacity and what Fred Moten coins as “fugitivity”-- “a desire for and a spirit of escape and transgression of the proper and the proposed…a desire for the outside, for a playing or being outside, an outlaw edge proper to the now always already improper voice or instrument”-- creates portals for seeing and being seen.

Also, a fun fact, the chinoiserie pattern was used by the founding fathers (Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, etc..) to reinforce symbols of enlightenment that uphold race within architecture commonly found in Virginia...

But, I am curious and would like to ask the same question. What materials are you working with right now, and how does your background inform those decisions?

Dana Davenport, Dana’s Beauty Supply ~and relaxation space~ (detail of family photo)

, 2021,

Installation at Recess Art

, Photography by Mary Kang

DD: Wow, thank you for so eloquently sharing your relationship to the materials you’ve been working with. Your use of material and the histories that they hold really resonate with me. As you know, I was born in Newport News, Virginia and raised in Seoul, South Korea. Although Virginia is not a place that I’ve spent much time in, much of my dad’s family is scattered throughout the Virginia area so it’s where we meet for family reunions and such. As a kid, I went through many different phases. One of those phases was an obsession with America (and therefore Virginia) and claiming my Americanness to my friends who also went to school on the military base in Seoul. It sounds silly to want to “prove” your Americanness while literally going to school on an American military base. But, you know how kids can be. They’ll find anything to pick on someone about. Haha. What I didn’t know or understand at that time is how fraught of a place Virginia was and still is. The way that Virginia existed in my mind as a place that validated my belonging even though I was thousands of miles away, versus the reality that even if I lived there, there would be a constant battle for the contributions of my ancestors to be acknowledged, was definitely a plot twist for me and something that I’d become more exposed to as I’d visit more frequently over the years in middle and high school. There is something eerie about being in Virginia, walking on the land, yearning to connect with ancestors, cultures, histories, and languages that have been buried in the soil. When I feel this yearningness, it’s humbling to remember that these histories exist through and within me.

I didn’t know that the first significant wave of Korean laborers worked on plantations in Hawaii! This is really interesting to hear, as my partner and I visited a friend in Hawaii a few months back and didn’t know much about the migration of Koreans (and other Asian folks) to the islands.

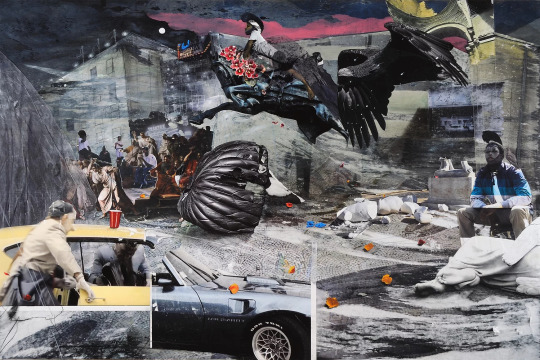

I’m really interested to learn more about your exploration of chinoiserie patterns. I see your use of it in Licked Until Your Tongue Rubbed Raw, 2022 and in On Belonging: The Space In Between, 2021. Are you creating the chinoiserie patterns yourself? It is quite interesting how this pattern has shape shifted and been adopted into Black interior aesthetics. I’m intrigued by aesthetics that seem to exist in between and thinking of ways that we can create visual languages around Black and Asian experience, solidarity, and futurity. For the past several years, I’ve been working with synthetic hair and hair care products as a material that binds Black Americans and Korean Americans through the beauty supply industry, an industry that we know is overwhelmingly Korean-owned with a primarily Black consumer base. Prior to this, I was doing a lot of performance work but became weary of having to rely on the presence of my physical body in my work in order to discuss not only the tensions that I felt in being a Black and Korean woman but also everyone else's interpretations and projections of the conflicts between Black and Asian communities. It was a lot to carry. After a particularly uncomfortable performance at a “prestigious” space with a nearly all white, generationally rich audience, I took a step back from performance. At that time, I simply didn’t know how to continue doing that work in a way that was also protective of my body and my experiences. So, in saying that, I was seeking out a material that could serve as a proxy for my body. I began to think deeper about hair care and the experience in obtaining these materials. When I first moved to NY from Korea after graduating high school, I remember being baffled after walking into a beauty supply store and seeing that the folks behind the counter were Korean. This was odd, as there are basically no beauty supply stores that cater to Black hair in Korea, and there wasn’t really any talk of how this industry in the US is dominated by Koreans. I started to experiment with speaking a little Korean here and there and it would not only confuse the Korean employees and store owners, but it’d severely improve the treatment that I received. I’m talking, free samples, the works! It was an uncomfortable reality of privileges that I hold. Disclaimer: I don’t speak Korean fluently so it took some courage and pepping myself up to actually speak Korean in public. All of this being said, I became obsessed with hair, hair care, and the beauty supply as a space to be reimagined where we can have critical dialogue around our collective history while envisioning Black and Asian futurity. In this reimagining, I return to the past and think about other businesses that are Asian-owned, in Black and Brown neighborhoods and how they are some of the few spaces where Black and Asian folks may find themselves intermingling. I think about the murder of Latasha Harlins. I think about my mom’s friend who’s worked at a beauty supply store for more than 20 years in Virginia (my mom and her friend are both Korean). I also think about early Chinese immigrants that opened grocery stores that served former slaves. They were successful because they offered goods at lower prices compared to plantation commissaries that inflated their prices to keep former slaves in perpetual debt. And of course, I consider the ways in which The National Housing Act of 1934 made it nearly impossible for Black folks to start businesses within their own communities.

Dana Davenport, Dana’s Beauty Supply ~and relaxation space~

, 2021,

Installation at Recess Art,

Photography by Mary Kang

DD: You studied Painting and Printmaking in undergrad at VCU and are now at UCLA in New Genres. Can you talk a bit about your journey from painting and printmaking to sculpture, performance and video?

LR: Thank you for your openness and criticality in articulating the tensions that arose from your experience, material practice, and journey as an artist. I resonated with many things you said and even found myself getting out of my chair and snapping my fingers in agreement because of it. Haha.

Firstly, when you were talking about your experience growing up in Seoul on a military base and feeling the need as a child to prove your Americaness – your virginianess -- was something I connected to. In my case, because I was born and raised in Charlottesville, it was not necessarily my Americaness I felt the need to prove, but my Asianness. I went to a predominantly white, upper-class private school, and I distinctly remember this moment on the playground when I was asked by a white classmate “What are you?” At this moment, I already knew I was different. I was one of maybe three Black kids in my grade for many years, but as a child, I had recognized the cultural currency my mom held as a Korean woman that my dad did not as a Black man. At that moment, I felt the need to legitimize my Assianness because I thought it would give me some sort of advantage. I longed to be accepted and included by my peers. There was always a feeling of not being accepted by the Black community or the Korean community. This was for a lot of reasons. My mom's relationship with her motherland was severed. Her connection to Korea and any sort of Korean roots is fragmented. Mine even more so. I did not grow up around other Koreans. My body also gets read as Black in the US. My Blackness has been prioritized because it has been perceived as more of a threat. How do we begin to talk about psychological violence? How do we begin to talk about these entangled and complex realities and relationships between Black and Asian futurity? How can we talk about belonging and arrival in the context of Black and Brown worldmaking? What are the tensions between belonging and fugitivity? Beauty and horror? Opacity and transparency?

Right now, I’m really sitting with Saidiya Hartman's offerings around monstrous beauty.

I say this and also recognize the privilege and complexities I hold being mixed-race.

I love your work and how you use the body as a material. Not just physical body, but hair as body. You asked about my relationship to the medium, particularly studying painting and printmaking and working primarily in sculpture and installation now. My journey was very similar to yours in a sense. In high school, I began to consider art as a career, and my introduction was primarily through painting. I fell in love with oil paint. The layering of color and texture, the manipulation, and the capacity for a single brush stroke to encompass expression and emotion. I went into undergrad knowing I wanted to be a painter. After the first year, that reassurance shifted. I took a time-based media class, and I was not great at making videos– but I did one performance, and something clicked. Through movement, material, place, and sound, I was able to tap into a sensory experience that felt more true to the emotion and criticality I was attempting to create in figurative painting. In the last two years of undergraduate school, I didn’t make a single painting. I began to work with hair and created a series of videos, sculptures, and performances that tried to pull out some of these tensions I felt navigating my identity.

I continued to make videos after undergrad, but I didn’t consider myself a sculptor at the time. It wasn't until after I graduated that I found object making through installation. Painting was such a distant memory at that point. Another reason I didn’t continue with painting is that I felt it was not able to do what I needed it to do. It couldn’t tell the story I was trying to convey, and the history of the medium is so fraught. I didn’t want to contend with it.

I then moved into performance. In the work with oranges, I was thinking of my body as orange. But, as I continued to perform, I would similarly get triggered. Especially performing to predominantly white audiences. This felt unsafe for my body and experiences. It got so exhausting that at one point in “My body is the architecture of my Every Ancestor,” (performed a few days after the Atlanta spa shooting) I performed inside the gallery through their “storefront window” making the audience watch the performance outside. I then pushed back the audience even further — to the sidewalk— to view the performance. I was trying to create distance, some sort of mediation of the violence of the audience, their gaze, and their interpretations of my body. I felt like an open wound, especially after my first year of graduate school. I felt vulnerable and constantly oozing…constantly being split open. Looking back, this is the moment I subconsciously turned to material as a stand-in for my body. A proxy that could be read in relationship to, but without my physical presence. This also allowed for larger narratives and histories to merge into the work.

As I continue to make performance and work that is non-archival in nature, I ask myself, what does it mean to build a practice that resists collectability/ownership and demands extensive care for its upkeep? As an ethos, how can I resist the market as a place of only transaction?

Going back to your question surrounding chinoiserie. I am starting to create the patterns myself. In "On Belonging" and "Licked Until Your Tongue Rubbed Raw '' I had not started to create my patterns yet. At the time, I was still grappling with the dissemination of these patterns. For my mom, it was less about the particular landscape within the pattern but more about the blue, white, and porcelain combination. You can now see within an American interior aesthetic, blue and white has become an interior decorating staple. The blue and white pattern has been adopted by many different cultures around the world. The interpretations, redactions, translations, adoptions, and reinterpretations don’t stop haha. This was intriguing to me because this pattern is synonymous with the colonial project. At that moment in time, I wanted this aspect of the work to be digested. The everydayness of this violence within this pattern. I was using generic interpretations of the chinoiserie to talk about the interpretation of the interpretation. The didactic. The performance of it. But now, I am less interested in that and more interested in how the pattern can be flipped or incorporated into my myth-making to generate something else. Similar to how I witnessed the pattern functioning in my home - a place of a combined Black and Korean interior aesthetic (though blue and white stems from a Chinese tradition). I am currently meditating on the beauty my mom has created through proximity of objects within the home. The rituals she has implemented so our family can begin to mend generational ruptures. For her, these mendings happen with food, and at the table. A type of physical and emotional nourishment that can happen in the home. This ability to mend and create beauty out of the monstrous, out of violence— it is a superpower. It is the Black radical tradition. It is the in-between. It is in the liminal. It is neither here nor there. It is the place where entanglement creates new futurities. It is everything all at once.

I am also curious about the aesthetic merging that happens in your work. Especially the chandeliers and Synthetic hair. Can you talk more about why the chandelier and how you landed on that form/object?

Also, in your works ``Much Love” and “experiments for relaxation” you’re working with multiple notions of care. How are you thinking through the registers of care that are required to nurture a critical dialogue surrounding Black and Asian futurities and solidarity? More specifically, What care is required to nurture yourself, your history, and your family's story? How are you thinking through care, and how do photography and family archives aid in telling this story?

Dana Davenport, 흑인 (heugin)-black person,

2017,

Performance at Watermill Center,

Duration: 2hrs,

Photography by Maria Baranova

DD: Ahhh, that very familiar feeling of wanting/needing to prove your Asianness. It’s wild that even at a young age, we unconsciously understand privilege and where one is situated within that system. While I was obsessed with America for a bit, that phase was short lived. My desire to “prove” my Asianness is unfortunately something that has taken much longer to shake off. In a lot of ways, my art practice played a huge role in that process. It provided me an unrestricted space to express all of the messy, contradicting, and nonlinear feelings that I was moving through. Initially, it was a lot of bottled up anger, a desire to be embraced by Korean culture while simultaneously resisting it in fear of rejection. This is most clearly articulated in my performance piece “흑인 (heugin)-black person”. In this performance, I write the word 흑인 repeatedly on a blank canvas on the floor. Gradually, the task became more aggressive resulting in exhaustion, examining the arduous notion of performing identity. Have you found that your relationship to Korea/Koreaness has shifted over time? And if so, what was influenced these shifts?

While our experiences differ in ways, I’ve arrived at similar questions. “How do we begin to talk about these entangled and complex realities and relationships between Black and Asian futurity?” I definitely don’t have an answer but something that I think about a lot is where are Black and Asian folks are interacting the most and under what conditions? I feel as though, within America, store owner/customer settings are the most common spaces in which Black and Asian folks gather. Commonly, Asian-owned shops in Black neighborhoods. So, that’s where I’ve started and how I arrived at the beauty supply as a space to be reimagined. I didn’t know that you worked with hair in the past! I’d love to see some of that work. I’m really fascinasted by your research around chinoiserie patterns, as it’s something that I’ve seen in so many places in totally different contexts but never stopped to think about how it lived between these spaces (I also never actually knew what the pattern was called). I always viewed it as an “Asian-coded” artistic style (often seen on vases and such) but then would also see as a wallpaper in some preserved colonial mansion in Virginia and not think twice about the overlap between the two. This pattern is truly a chameleon! I love how you are thinking about the next lifeform of this pattern, how it can shape shift to reflect a new culture, a combined cultural aesthetic, how it can be flipped as a tool to mend wounds. As you said, it is our superpower to mend and create beauty out of the violence we and our ancestors have endured. When I began working with hair, I started with simple domestic objects. A vase, slippers, rug, etc. I wasn’t really sure why, I was just drawn to it. As someone who studied Photography in undergrad, I hadn’t really considered myself a “maker” and definitely didn’t have the tools at that time to create the sculptures that I’d envisioned. Out of the many ideas that I’d jot down (and often talk myself out of trying) creating a chandelier was one that stuck. In the Summer of 2018, a family friend, Dan, offered to teach me how to weld. That changed the game for me as far as the tools that I had to create. Initially, I was drawn to the chandeliers because of their ability to elevate a material that, when worn and activated by Black folks, is criticized as ghetto, cheap, fake, and unprofessional. As I’d hang them within my studio and home, incorporate them in installations, and hang them in gallery spaces, they began to take on a protective role, setting the tone for whatever room their in and requiring that viewers look up at them with appreciation and awe.

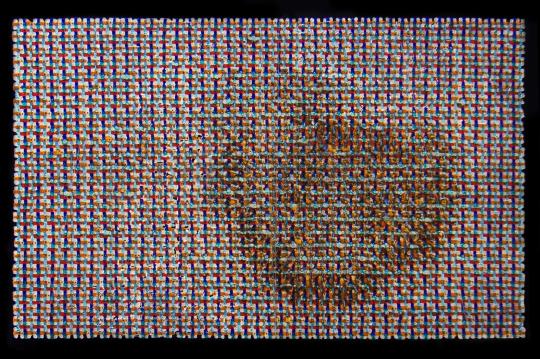

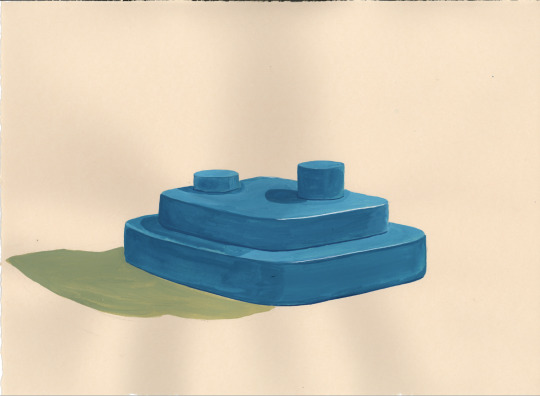

Dana Davenport, Box Braid Chandelier #3, 블랙파워 (beullaegpawo)-Black Power, 2021, 30in x 25in, Steel, plastic beads, modeling clay, synthetic hair from Hair Style 21 (Online)