Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This Blog Moved

Hey reader. Just a heads up that I’ve changed platforms to help me organize future posts and give the blog an makeover. You can find it here: https://cumbersomelift.blogspot.com/

0 notes

Text

Spiritual First Aid (Resources Pt. 1)

When I was deconverting at university, I spent months poring over sacred texts, spiritual commentary, and works of philosophy to try to find what’s true. I thought what I needed was a theological rehab – to detox from harmful ideas and to replace them with healthier ones. But what I really needed was more like spiritual first aid – something to immediately address the frustration and guilt I was experiencing right then and there. I mourned the death of God even as I rejected him, and I felt tangled up in this ambiguous sense of loss.

Apart from a few close friends, I deconstructed privately. I thought the more open I was about my questions the less social support would be available from my community. (This was only half true.) I had also internalized the idea that I was responsible for the spiritual well-being of those around me, so I should keep these potentially destabilizing questions to myself because to do otherwise would be morally irresponsible. I would have said that it’s like throwing the biblically inexperienced into the theological deep end (which is patronizing and ridiculous). So, I often felt alone. Years of immersion in evangelical culture made me blind to the shame-loops that fed that sense of isolation and deaf to the language I needed to describe my own experience.

Even years later I’m still figuring that out. But I’ve found the trick to unlocking that language is just tuning in to the right conversation. These days, they are happening all around us in podcasts, books, and other media. Some of the best advice to those deconstructing—and in general— is simply to keep reading.

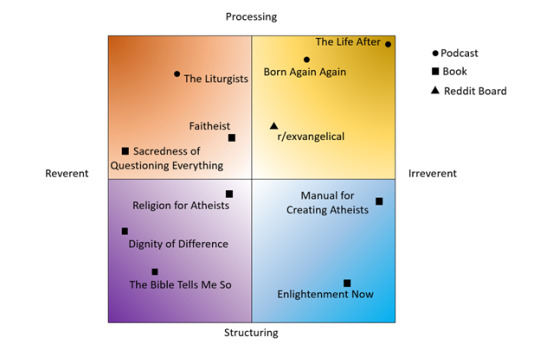

So here are some of the resources that I had (or wish I had) when I was deconstructing, and a map to show how they meet different needs. After all, someone reshaping their faith (deconstructing) needs something different than a someone dropping it entirely (deconverting). Those of us who are hurting need something different than those who are rebuilding. So, here’s the chart I’ve used to help catalog the books I’ve found most useful.

The reverent/irreverent x-axis describes whether the author sees religion as sacred and useful or delusional and hurtful. So, on the reverent side, you have secular pluralists who see religion as a force for good and Christians boldly asking the hard questions in an authentic attempt to deepen their faith. On the irreverent side, you have secular thinkers who say organized religion is mostly just harmful, but it’s normalized in ways that make this hard to see. If you’re deconstructing as a Christian – because you think the earth maybe wasn��t created in 7 days or because the Bible is hard to make sense of – then I’d point you to the reverent side of this map. For those deconverted or deconverting, you might find the irreverent items more relatable.

The processing/structuring y-axis captures whether the writer is exploring the personal experience or writing about the structure of beliefs that follow. Writers who are “processing” are often those who have abandoned a formerly cherished belief and are working through that change out loud with friends. “Structuring” writers are a few steps removed from the tension but can help answer the question "What am I supposed to believe now?" These writers can help us replace bad theology with a healthier, coherent alternative.

For brevity, this post is focused solely on the processing quadrants – I’ll pick up the structuring quadrants another time. These are a handful of resources that I’d describe as being Spiritual First Aid because they help make sense of pain and can even provide community for those struggling. I have a few books listed, but many of these are literal conversations in the form of podcasts. As you’re reading these consider adding them to your Facebook feed, Spotify rotation, or Amazon wishlist.

Oh. And one last thing: the point of this series is to encapsulate for the church what it’s like to deconstruct and how that impacts relationships. If you’re a person of faith reading this, I encourage you to listen in on some of these podcasts yourself – not because I think they’ll deconvert you but because they’re a primer for bigger conversations. They can be immensely helpful if you want to know reasons people leave the faith, why they might harbor resentment toward the church, and whether your church is participating in these harmful practices (I know that I was). So, even if the quadrant is “for you” it can offer a sense of what experiences others are up against.

Irreverent and Processing

These are conversations where people explore personal experiences of religious trauma syndrome, process the emotional damage of belief, and reject their spiritual upbringing with varying degrees of force. These can be useful for knowing you are not alone when you feel betrayed or hurt by religion in ways that are hard to express. They may even supply language to better articulate those experiences. Everything I listed here is produced by deconverted Christians who have firsthand experiences deconstructing their faith and fishing out the toxic ideas they once accepted.

The Life After (Podcast)

Here, two deconverted pastors interview courageous people about their journey of faith deconstruction, unraveling religious indoctrination, spiritual abuse experiences, religious trauma, mourning the death of God, and what it's like rebuilding a community after leaving Christian fundamentalism. Their trauma-informed approach and irreverent humor add levity to a series of heavy topics. (If this paragraph is the first time you've ever heard of spiritual abuse or religious trauma then you can read a short blurb about religious trauma syndrome (RTS) from one of the lead researchers on the topic, here.)

I found two episodes on purity culture and RTS with sex therapist Jamie Lee Finch to be especially illuminating. These are the episodes "Unbuckling the Bible Belt" and then “You Are Your Own.” The best introduction to this podcast might be the episode called “Born Again Again” with Katie and Joe Bauer who talk about deconstructing as a couple and what it’s like for spiritual leaders to leave the faith.

The Life After also has a Facebook group that began as a trauma-informed home base for listeners to relate their deconversion experiences, but now it hosts book clubs, a mentor network, and a stream of blasphemous insights from those who have deconstructed into non-Christian spirituality or secular humanism. They even have affinity groups focused on specific challenges like how to be body-positive after living in purity culture or deconverting in a marriage where one partner stays a believer.

Born Again Again (Podcast)

Two former worship leaders talk through their own deconstruction experiences and how they make sense of their spiritual upbringing as secular adults. They have some fascinating stories about their experiences with Campus Crusade for Christ and the Hillsong movement. In fact, in "This Is Your Brain on Worship" the hosts share how they had a formula to help congregants speak in tongues based on hypnosis. Wild!

Another is "A Personal (or Abusive) Relationships with Jesus?" where the hosts show the dark side of trading religion for a "relationship with Jesus.” They start with the descriptions provided by Campus Crusade for Christ, John Piper, and Billy Graham to define what a relationship with Jesus means, then they break down how these definitions in any other context are textbook cases of abuse that are just normalized through false consensus. They also talk about what it did to them to buy into this relational framework themselves, and how Cru’s organizational structure can pressure young college students to do the same.

r/exvangelical, r/exChristian, e/TrueAtheism (Reddit Boards)

r/exvangelical and r/exchristian are moderated communities of post-fundamentalist Redditors. This might be of use for those who describe themselves as something like "culturally Christian but theologically agnostic.” It’s a moderated group of individuals that works like the Life After Facebook group. People share their experiences, seek advice, and connect on the process of deconversion. It’s a very welcoming, affirming community where pretty much every trepidatious Redditor is met with a chorus of supportive replies.

r/TrueAtheism is similar but not specifically made up of post fundamentalists. It was recommended from the Born Again Again hosts. This particular thread of “honest questions from an atheist” is an incredibly exhaustive list of troubling bible verses and hard-ball questions about the faith that many of us may find relatable or articulate a dissonance we’ve experienced before.

Reverent and Processing

These may be good resources for people who grew up Christian and have an active personal faith but aren't sure where they fit anymore. After all, the church has changed a lot in the last ten years. Maybe you describe yourself as a Christian mystic, agnostic, or just a believer trying to find your place. If the phrase "spiritual nomadism" resonates with you, you might feel at most at home exploring questions of faith with these spiritual thinkers.

The Liturgists Podcast (Podcast)

Michael Gungor and Co. are believers in the in-between talking about faith issues and modern events in this podcast. Sometimes we conflate deconstruction with deconversion and overlook the ocean of gray area between Christian fundamentalism and secular humanism. This podcast is hosted by a community of believers that live in that space.

In "Is Deconstruction Bad?" they talk about the emotions felt in deconstruction, the social cost (especially for spiritual leaders), and how to embrace a healthy outlook in the midst of it. It's a serious look into what is lost when we challenge our assumptions about faith and why it becomes hard to stop. A similar episode is called "Does Being Good Mean My Beliefs Shouldn't Change?"

Among my favorites, though, is "Swapping Fundamentalisms.” Sometimes we move from one restrictive, dogmatic set of beliefs to another because we've internalized fundamentalism so thoroughly that we take it with us wherever we go next.

Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious (Book)

Chris Stedman was raised in a staunchly homophobic faith community when he began to realize he was gay. His memoir is a story about his unconventional deconversion experience. Stedman would say that the hostility expressed by his church toward the LGBTQ community is hard to too similar to what new atheists express toward the church today. Stedman rejects militant atheism for a more pluralistic approach to interfaith relationships. He believes that mutually incompatible religions can exist in harmony and not just competition.

He's an atheist committed to interfaith organizing and believes that rallying faith groups on the common ground of our humanist ethics can help us create a better world together. If you think the new atheists are too harsh on religion or overlook the good that religion has does for the world, then you might be sympathetic to his approach.

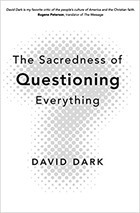

The Sacredness of Questioning Everything (Book)

David Dark a Christian writer who thinks that if you read the Bible and don't have any questions then you weren't reading very closely. "The God of the Bible not only encourages questions; the God of the Bible demands them." In The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, Dark talks through why interrogating our belief is a spiritual discipline and what believers fall prey to once they stop.

Importantly, Dark shows how deconstruction isn't just for the deconverting. Instead, it's an act of theological hygiene. If the God we believe can’t accept protest, interrogation, or dissent, then we’re in trouble. In fact, without the right questions, our conception of God can exist strictly to keep us in line and keep our heads down so we don't get burned. Dark is a Christian who wants to disabuse Christians of that narrow conception of God and show why questions are essential for spiritual growth.

Conclusion

So there’s my spiritual first aid kit. Hopefully at least one or two of these resources will resonate with you. I can say that at different points in my life, each of these things provided an insight that made deconstruction less shameful and more clear. If you have other books, podcasts, or communities that have helped you process in deconstruction, then don’t hesitate to add them in the comments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Trumpification of Evangelicalism

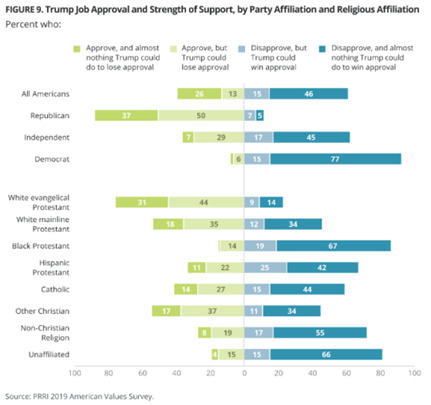

About 85% of white evangelical voters cast their ballot for Trump in 2016. In 2019, 77% of white evangelicals approved of his job as president, and 81% said he fights for what they believe in. Whether we like it or not, Donald Trump has become an avatar of white evangelicalism and this has substantially damaged the reputation of the church. Rather than being known for it’s love, it’s known for it’s president.

In an interview with the Atlantic, an unnamed pastor tried to describe what the infusion of Trumpism means for American Christianity. He put it like this:

“There are many reasons why young people are turning away from the Church, but my observation is, Trump has vastly accelerated that trend. He’s put it into hyperdrive.”

“For decades Hollywood has portrayed conservative Christians as cruel, ignorant, greedy, and hypocritical. For 20 years I have worked, led, and sacrificed to put the lie to that stereotype, and have done so successfully here … Because of how we have served the least of the least, city officials, school officials, and many atheists have formed a respect for Jesus and his church. And I’m watching all that get washed away.”

“Yes, Hollywood and the media created a decidedly unattractive stereotype of Christians. And Donald Trump fits it perfectly. Made it all seem true. And sadly, I now realize that stereotype is more true than I ever knew. It breaks my heart... He’s everything I’ve been trying to say isn’t what the church is all about. But sadly, maybe it is."

Many who saw the church as institution of moral clarity in our youth are now left disoriented by its enthusiastic endorsement of Donald Trump. In the words of the pastor, we began to feel like we were wrong about what the church actually stood for. What if what the church stands for is Donald Trump?

I suspect that many Christians wince at this suggestion. Maybe it sounds derisive or unfair to draw the conclusion. Maybe it's the empty generalization you'd expect from an embittered nonbeliever. In this post, I want to explain why linking Trump to the church isn’t a symptom of “Trump derangement syndrome” or a product of liberal ad hominem memes in my news feed. I believe this because it’s what the church tells us. When researchers asked white evangelicals about their political attitudes, their warm feelings toward Trump consistently set them apart from other Americans. Even apart from other believers.

In the Pew results I mentioned earlier, 77% of white evangelicals said that they support Trump in 2019. For reference, in 2018, the percent of American Christians that said that they "believe in the God of the Bible" was 80%.

Based on these results, Christians are about as likely to believe in God as white evangelicals are to support Trump.

Reconnecting with evangelicals is harder to do when their political icon gets his kicks from pwning the “liberal snowflakes” like me. But more importantly, it’s harder because the church is being remade in his image. If you compare Pew results from early 2016 to now, it appears that the white church has moved from tolerating to accepting to celebrating Trump’s pugilistic style.

From Tolerable to Upstanding

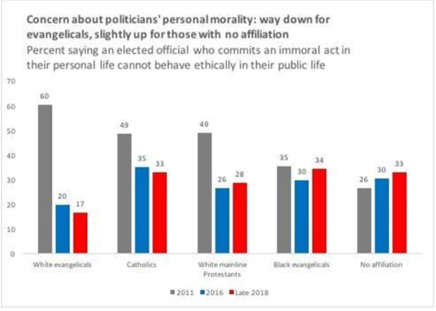

A 2011 poll from the Pew Religious Research Institute (or Pew) asked Americans this question: If a politician committed an immoral act in their personal life, are they unable to act ethically in their public life? Compared to other religious groups, white evangelicals drew the hardest line -- 60% agreed that if you're unethical in your personal life, you can’t be trusted to do the right thing in politics. Trump’s Hollywood Access tape leaked in 2016 in which he bragged about sexually assaulting women, saying that he liked to “grab ‘em by the pussy.” That year Pew asked this exact question again. This time, white evangelicals saw things differently.

In 2016, only 20% of them agreed.

This 40% swing is one of the wildest poll results from 2016 (which was a wild year for poll results). In the span of 5 years, white evangelicals went from being the most concerned about a politician's personal conduct to the least concerned. Shortly after, a bulwark of the moral majority allied itself with a thrice-married reality TV star who had previously featured on the cover of Playboy magazine. Over time, white evangelicals grew not just tolerant of his behavior but began to identify with it.

Fast forward to 2020. In a poll this year, a majority of white evangelicals described Trump as “morally upstanding” (61%) and “honest” (69%). I don’t mean to overinterpret two polls, but this result is a remarkable extension of the 40-point swing we saw earlier. Together, it seems like the majority of evangelicals said in 2016 that, “Look, even if Trump’s unethical in his personal dealings, he can still be a good politician,” and now say in 2020, “Actually, he’s not unethical at all, he’s morally upstanding.” That’s a remarkable shift in moral judgement across four years.

When I think of Trump’s behavior between 2016 and 2020, here are three things I remember:

On August 7th, 2017, Trump complained that it was “ridiculous” of Megyn Kelly to question his past treatment of women on the debate stage. He proceeded to insult Kelly on live television, saying she “had blood coming out of her eyes. Or blood coming out of her wherever.”

On October 16, 2018, Trump used his Twitter to call an adult film star with whom he had an affair “Horseface.”

On July 14, 2019, Trump told four congresswomen of color to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came.”

From the outside looking in, it’s strange that in the same four years Trump moved from being not-quite-disqualified to being “morally upstanding” to a majority of white evangelicals. I've wondered whether this would change if we read Trump's tweets aloud at a Sunday worship service every week. Take a look at his latest and judge for yourself. For whatever reason, he’s grown on the church.

Fifth Avenue Evangelicals

A striking majority of white evangelicals viewed Trump favorably in 2019 (71%) but many believers took it a step further. About three in ten white evangelicals checked a box that said, "I approve [of Trump] and there is almost nothing Trump could do to lose my approval.” Famously, Trump joked that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue in broad daylight and not lose support. That's why asking if "there is almost nothing Trump could do to lose my approval" is worth the ink. It appears Trump's Fifth-Avenue supporters are largely in the halls of the white church.

Maybe you're thinking, "Sure, but those people aren't real churchgoing Christians. Upright believers are straight-laced and polite and love thy neighbor.” Well, not exactly. It turns out that white evangelicals who are fondest of the president are usually the ones who attend church weekly. Those who attend church less frequently are less supportive.

So, the idea that evangelicals are holding their nose to vote for Trump I have to reject. I mean, most Americans (74%) wish Trump would be more presidential in his personal conduct, but that view is only shared by about half of all white evangelicals (53%). The other half don’t see an issue. In fact, over one in ten white evangelicals said that Trump’s personal behavior makes them more likely to support him.

God-and-Country Believers

Trump has reputation for fear mongering about immigrants, but many believers share his view. In fact, these attitudes have become an empirically defining feature for a major swath of the American faithful. Pew’s new typology gives them their own category called "God-and-Country Believers." They’re defined as "Those who are socially and politically conservative, most likely to view immigrants as hurting American culture” and about a third of highly religious Americans fit this description.

If the data is any indication, the majority of God-and-Country Believers are white evangelicals - they consistently report the strongest, most negative attitudes toward immigrants than any other faith group.

More than frequently than any other group of believers, white evangelicals:

said they have a negative view of immigrants (17%)

said that immigrants are invading the country (75%)

said immigrants increase crime (62%)

said that immigrants create a burden on communities by using social services (71%)

were least likely to support sanctuary cities (27%)

were most likely to support family separation policies for undocumented families (39%)

I personally believe that Trump is a major force shaping these attitudes, too, but I could be wrong. Others say that Trump is just the embodiment of beliefs white evangelicals have always held and is finally “telling it like it is.” Robert Jones, the director of Pew Religious Research Institute and a white evangelical himself, explained this in his book The End of White Christian America. Jones describes these attitudes as the result of the "symbiotic relationship between Christianity and white supremacy" that's existed for centuries.

He explores this further in his newest book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. Here, Jones argues that white evangelical support for Trump is best understood in the context of that racial history. MLK remarked that America’s most segregated hour is always 11am on Sunday morning, and Jones explains why this isn’t a coincidence. Many of these faith traditions were originally predicated on a desire for white protestant cultural dominance, and until now, that dominance has never been challenged. He writes:

By activating the white supremacy sequence within white Christian DNA, which was primed for receptivity by the perceived external threat of racial and cultural change in the country, Trump was able to convert white evangelicals in the course of a single political campaign from so-called values voters to “nostalgia voters.”

Trump’s powerful appeal to white evangelicals was not that he spoke to the culture wars around abortion or same-sex marriage, or his populist appeals to economic anxieties, but rather that he evoked powerful fears about the loss of white Christian dominance amid a rapidly changing environment.

The book is meant to provide a historical explanation for the trends he’s discovered in his research. Many of these findings I’ve reporting throughout the post. Jones argues this history explains why the white evangelical church has historically lagged in support of racial justice efforts where it hasn’t directly opposed them.

Why This Matters to Non-believers

I’ve spent a lot of time here writing about why the association between Trump and the white Christian church is warranted. I haven’t said a lot about why that’s a problem. I’m not sure I need to, but here are few reasons, anyway.

It’s a problem because Trump bragged about sexual assault on tape. It’s a problem because he shared a video saying “the only good democrat is a dead democrat.” It’s a problem because Trump peddled conspiracies about Obama not being a real American. It’s a problem because he tweeted a white power video. It’s a problem because he ordered an alt-lite militia group to “stand by” in case he needed them to fight after the election. It’s problem because it’s now genuinely unclear to me whether the church finds these behaviors morally objectionable.

I think it’s also unclear to Trump.

Here’s why I say that.

Do you remember at, the height of civil unrest, when secret police fired without warning on international journalists and peaceful protestors in front of St. John’s church in DC? The clergy demonstrating for racial justice were forcibly removed so that Trump could be photographed in front of their church with a Bible that wasn’t his. That display of fraudulence and tyranny was ostensibly a performance for Trump’s base: the white evangelical church.

Trump thinks he knows what that church wants and he’s largely correct.

It’s possible that white evangelicals find all of Trump’s bullying and lying are consistent with an upright life. It’s more likely that they were overlooking what I’ve described here entirely. Either way, I think it requires explanation. Why the church is willing to support or even overlook this behavior needs to be talked through. That the church was even capable of this was a shock to many.

This is, I think, one of the most urgent and difficult conversations between evangelicals and nones that’s required for our mutual understanding.

0 notes

Text

Fire and Brimstone

A few years ago, a close friend of mine came out to their parents as a non-Christian. Distressed by their child's infidelity, they said that if they had known this would happen then they would have never had kids in the first place. In effect, things would have been better if they were never born.

That’s a cruel thing to say to a child, but it’s also refreshingly honest. I think if more of us took the fundamentalist doctrine of hell seriously, then conversations like this would be more common. These feelings might surface for others. Fundamentalism of any kind can create the circumstances that lead kind and gentle people say remarkably harsh things.

Damnation complicates interfaith relationships because it raises the stakes in a way that's rarely acknowledged. For me, it also dredges up a series of experiences I had as a child preoccupied with the fear of hell. I've since discovered that this is not uncommon. So before I talk about the doctrine as a barrier to relationships, I wanted to share a few experiences of why I see efforts to internalize the doctrine of hell in children as emotionally manipulative at best and abusive at worst.

Growing Up Damned

Growing up in a fundamentalist tradition, I thought about hell a lot. Of course, I was taught about hell a lot. I imagined it as an active, eternal torment and in long family car rides I wondered what it would even look like to inflict that kind of pain. I pictured immersion in lava pools, splinters under fingernails, hooks in one's skin, and being eaten alive by rats. I shuddered at these ideas. I also cried a lot. For a significant portion of my childhood, I believed I was nearly or definitely damned. Based on my 4th grader's interpretation of Hebrews 6:6 and an offhand comment by the Bible school teacher, I thought my joke delivered in a sugar rush at bible class was "mocking the holy spirit" - which I interpreted to be the unforgivable sin. I remember sobbing into my pillow and quietly weeping hymns that night just in case God was still listening.

Now that I'm older - and out of the church - some friends have shared similar experiences. Their damnation came from things like muttering "godammit" or was evidenced by their failure to speak in tongues. Some described recurring nightmares and even panic attacks that were triggered by fire and brimstone sermons. Many of the object lessons I received on hell are still burned in my memory.

A high school friend from a sister church recounted one object lesson about hell that she found especially devastating. One time at Bible camp, about half of the campers hiked to a hilltop for the nightly sermon only to find that many of their friends were missing. She took a seat among the empty chairs as the preacher welcomed them to heaven, and began preaching from Matthew 7 & 25. He read, "small is the gate and narrow is the way that leads to life and only few will find it" and "[the unsaved] will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life." At that moment, she began to hear her friends calling her name through the trees from the bottom of the hill. They, the unsaved, were begging her to come back. To save them.

I remember listening to a leader in my old church as he explained how the gospel is like a cure for cancer. "Imagine that everyone in your school is dying of cancer, and you have the cure in your backpack. Are you going to share it with them, or keep it to yourself? How selfish must a person be to withhold that from those that need it most?" I agreed and felt a fresh burden of guilt - how many people haven't I told? How many are unsaved from my cowardice and apathy?

Parents sometimes complained about these lessons and as a teenager I didn’t understand that. If we really believed these are the terms of existence shouldn’t be we made fully aware of their gravity?

I've often wondered if, as kids, we took the idea of damnation more seriously than our parents did. In an episode of The Life After, a therapist joins the hosts to talk about internalized fundamentalism and undoing what some call religious trauma syndrome. One host offers an explanation for why children (now millennials in their 20s-30s) experienced this growing up:

“This is something very interesting that I have not heard a lot of commentary on, but I’m really interested in exploring: A big part of the reason that our generation experienced so much religious trauma is that our parents' generation more or less chose Christianity, and our generation was born into it. So for us, growing up, it was our entire reality. Whereas for our parents, it was an augmentation to the reality they already knew. They were able to pick and choose what they let in, whereas we didn’t have a choice. That’s part of the gap. That’s why we can’t communicate [about the impact of our religious upbringing].”

The doctrine of hell was a defining aspect of my faith by design. While I personally think it's a stretch to call these experiences religious trauma or spiritual abuse, I'm troubled that emotionally manipulating teenagers this way is normalized -- even systematized -- in so many traditions.

Why Hell Matters for a Nonbeliever

I became a Christian universalist at 17 - even as a Christian, I thought to torture nonbelievers for their nonbelief was morally indefensible. But even after leaving the faith entirely, that fundamentalist doctrine has caused me more pain than any other. It also makes interfaith relationships much trickier to navigate.

One reason for this is that I find myself preoccupied by its normalcy. In fact, I'm comfortable saying that my damnation is the primary lens through which I view the church. Every steeple, every cross on the highway, and every bible verse on Facebook is a reminder that a considerable portion people in this country would not object to my eternal suffering as long as it's at the hands of the right deity. That number includes many family members and people I grew up with. Maybe you can see why that’s a little preoccupying.

This means that my damnation often becomes the unshakeable backdrop to any relationship that I have with a Christian person. Even when they’re not thinking about it, I almost certainly am - and I want to know what they're thinking about it. There's not a clear way to introduce that into a conversation, but I'm always curious. I mean, maybe I want to be friends, but it's awkward if you think your God will call for my torture in fifty years. In many cases, there’s no aspect of faith that I want to engage believers on more than this point exactly. I rarely do, because it's impolite to ask that kind of question, and when the conversation arrives I often find myself ill-prepared to engage.

This is because I find communicating the relational toll of this dynamic to be almost impossible. Asking someone to take my perspective is hard because, for one, there is a lack of any secular analogue. In that past, I've asked whether it would change our relationship if I believed that eating animals for food was a sin. (I'm a vegetarian.) Would it change anything if I believed that, if you don't also become a vegetarian, you will be reincarnated as an animal that's needlessly slaughtered forever? That if you stop eating meat now, you can save yourself this fate, but that I'm afraid your late omnivorous relatives are already in anguish for their crimes? Of course I don’t want that for them, and it’s sad but it’s true. That I don't make the rules, but also the rules are fair? Maybe our dinner parties would be a little more awkward. Maybe you wouldn't let me around your kids. Or invite me to dinner at all. You can see that our interactions might be a little strained, and you might have some questions about what this means for our relationship.

Why Hell Matters for Believers

The doctrine of hell also impacts Christians who have relationships with nonbelievers. It raises the stakes for any Christians willing to have interfaith relationships by casting nonbelievers as both a soul that’s in danger and a spiritual threat. This is why I've seen preachers tell new Christians not to befriend nonbelievers, and why I've had parents tell their Christian kids to stop hanging out with me. I think this advice is hateful and misguided, but more than anything it’s self-preserving and intuitively follows from the doctrine of damnation. Moreover, it puts many of the necessary conversations out of reach.

The mathematician Blaise Pascal invented a tactic of evangelism that won souls by threatening them with Hell. (He was also a lot of fun at parties.) It’s called Pascal’s wager, and it goes something like this: “If you’re an atheist then you might as well be a Christian, because if you’re right then you’ll die and be dead, but if you’re wrong then you’ll die and be damned. So, just be a Christian. Why roll the dice?” It's about as effective for evangelism as it is unethical. But it's an excellent retention technique for those already in the pew. If you're a Christian already persuaded of the stakes, it's a paralyzing reminder about the cost of defecting.

When I was a Christian, I found the risk of dissuasion utterly terrifying. I read up on apologetics mostly to reassure myself that I could parry every objection with my faith intact if any atheist came looking for a fight. But when the atheist is a loved one, the stakes get even higher. It’s not enough to defend myself anymore. I have to bring that person back to the fold before they're calling my name from the bottom of the hill. So many believers decide to withdraw altogether. By taking a step back, they can at least say it's in God's hands. But the relationship is too risky to pursue.

My point here is not to say that the doctrine of damnation is incorrect -- though I obviously think that. My point is to say that it’s damaging. A judgment about whether another person’s life stance makes them worthy of suffering will matter for that relationship, and in the end that judgment is what the doctrine is about. It’s especially preoccupying for the deconverted when we assume that Christians take the belief as seriously as we did when we internalized it in childhood.

Addressing that assumption requires a conversation where we may find ourselves at an impasse: the doctrine of damnation is both preoccupying to nonbelievers and immobilizing to believers. I can't say that every nonbeliever wants to have this conversation or that every believer is so reticent. What I can say is that on three different instances, I have been contacted by an old friend who I thought was just catching up, only to discover they were enlisted by a concerned believer to "give me a nudge in the right direction." Presumably feeling ill-equipped to do this themselves, my family recruited someone with ministerial experience. I found myself heartbroken, not only by the pretense of reunion, but because I desperately wanted to have that conversation - not with a minister but with those closest to me. Not to interrogate or dissuade them, but to unpack the challenges that I'm writing about now.

Even as I'm attempting to acknowledge the pain on both sides of this discussion, I'm still blinded by my indignation about it. (I’m shaking as I type this.) Personally, I've found it a relief to openly ask Christians about this in a way that is as nonjudgmental as I can muster. Taking an exploratory posture toward these attitudes has at least put my wandering mind at ease and is a big part of why I feel less preoccupied with all of this than in years past. That's required self-restraint on my part and interpersonal courage on theirs. Relationships have grown as a result, and I consider myself extremely lucky for the opportunity to have them. I don’t know if it’s something talk through and be done with, but even if the questions may never be entirely resolved it’s a conversation worth having.

0 notes

Text

Intro: Cumbersome Lift

I quit my faith at 18, and I’m still learning to talk about it. I spent my high school years as a bona fide evangelical - going to church three times a week, leading communion, the whole schtick. But after two years spent majoring in Biblical studies I realized I could not, in good conscience, remain a Christian. That was a life changing experience for me, but it's not an uncommon one.

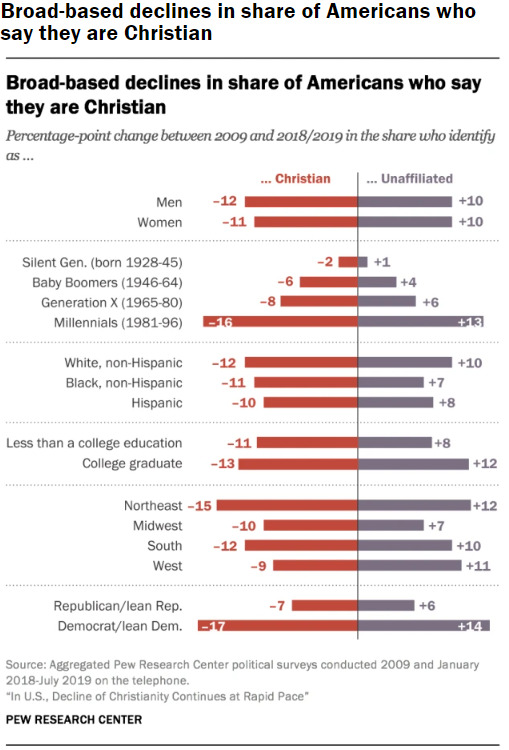

According to Pew, young people are dropping out of the church at a precipitous rate. A little over 15% of all millennial Christians stopped identifying as Christians in the last 10 years. This generation of Americans will be the first non-Christian majority in our history.

Despite the magnitude of this shift, I find that recently declared "nones" are sometimes resigned to being misunderstood. The assumption is that because vocalizing apostasy will jeopardize permanent relationships, it's best not to surface that reality at all. Especially among those closest to us. That's not always because the confession of non-belief would lead to outright rejection - in some cases, it does - but more often that it would result in harm and confusion. Because explaining non-Christian convictions would be so emotionally upsetting, many nones shield their believing family and friends from the most deliberate pieces of their identity.

But how long can that pattern hold? For many of us, our most permanent relationships are now characterized by a faith-divide. This is treacherous emotional territory. In my experience, it's not uncommon for recently declared nones to withhold their change in faith-identity from their family for years before finally disclosing it. Many don't do it all. As a consequence, these relationships can deteriorate into little more than rituals themselves, carried along by the inertia of our upbringing.

There must be a better way.

Brene Brown has said everyone wants to experience belonging in our relationships, but the experience of belonging is capped by our level of self-acceptance. I interpret this to mean we can only feel like we belong where we have already risked being authentic. Otherwise, acceptance is precluded by superficiality. If interfaith relationships are going to be places where belonging is possible, then what's required is authenticity. For many of us, this means surfacing the tensions have existed for years. It also means coming to terms with the fact that while persuasion is likely impossible, a mutual understanding is not.

The book Why I Left, Why I Stayed is co-authored by an evangelical leader and his secular humanist son. The book opens with each articulating their points of disagreement to their own satisfaction. But what's next is a chapter about what it means to authentically relate across the faith divide. In the end, they argue that it takes an unflinching commitment to that person. They describe it as a kind of love:

"The love we are talking about here, however, has less to do with flowery words and sweet emotions, and more to do with a fierce determination to know and be known by someone close and important to you, even when it is painful, so you can fully trust that person, even when you doubt his or her judgment."

The fierce determination to know and be known by those closest to me drives a lot of this blog series. But it's also about a few other things.

One is to signal to the nones like me that if they are experiencing a new kind of loneliness in the wake of their non-belief that they are not, in fact, alone. I wish I had known how common it was to question your way out of your faith tradition when I was an atheist Bible major in college. And I think I've done a disservice by not vocalizing that transition more publicly. So it's an attempt to normalize the migration already taking place. It's an attempt to challenge that taboo.

The second is to explain some of the reasons why I and others have left the church to that body of believers. I don't want this to be too navel-gazey, so I've interviewed other millennials about their experiences. Over the last few months, we've talked about what leads a person to root themselves in a faith community and then leave.

The third is to describe what barriers I see, as an atheist, in relating across the faith divide. I'll point to a few places where well-intentioned Christians can grind on the sensitivities of non-believers.

Here's what the project is not. This is not a new atheist apology. I'm going to be critical of the church where I think it's deserved, but the point is not to dissuade Christians - it's to be understood by them. No blog post I could write would do the job anyway.

I'm not a therapist or a scholar or a guru. I'm not someone who models an ideal balance in interfaith relationships. Like the rest of us, I'm an amateur at this. So, at times, I'll be unclear, overly emotional, and insensitive. In many ways, this is a public experiment. It's an attempt to contribute one side of a conversation that's as difficult as it is necessary. Necessary because our relationships are too valuable to give up, and difficult because we risk their permanent change.

1 note

·

View note