Following the cultural fears and anxieties that horror films have tapped into over the decades.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold” -W.B. Yeats

The zombie that we know today, the decaying, slow-walking monster who wants to feast on our brains, is a relatively new version of the zombie. When zombies first made their way onto American movie screens, they weren’t travelling in cannibalistic hordes; they were mindless, subservient slaves. Their origins can be traced back to the American occupation of Haiti [1915 – 1934], where many of the marines stationed in Haiti would return to the United States with sensationalist accounts of Haitian voodoo practices — most notably the folkloric tradition of raising the dead into personal slaves by a sorcerer or bokor.

While Americans brought back a [misappropriated] idea of the zombie, it nevertheless struck a chord with depression-era society. The zombie is a creature that is consistently associated with labour; the zombie’s labour is its sole purpose as they are brought back from the dead as slaves dead to toil endlessly in fields and factories. The surplus of labour that encompassed the great-depression no doubt had striking similarities to the idea of a mindless zombie, performing alienating labour at the hands of wealthy landowners.

The first film to solidify this image was White Zombie (1932), starring Bela Lugosi as the antagonist Murder Legendre, a wealthy Haitian factory owner who raises the dead to slave at his sugar cane factory. The scene in which the protagonist first visits the factory illustrates, in a depressing parable, the physical embodiment of assembly lines of workers — the zombies are no more than mindless cogs performing monotonous labour. The camera lingers for several minutes in a long take on this scene, capturing its dreariness and eerie familiarity.

“They work faithfully,” says a stoic Lugosi. “And they do not worry about long hours.” This echoes the sentiments of the depression-era bosses who took advantage of the economic crisis to bind desperate unemployed people to poor working conditions and long hours. And at this time, labour struggles were intensifying alongside rapidly expanding union membership in an attempt to fight this phenomenon.

The fate of the zombie is a stolen consciousness and livelihood, or spiritual connection to their labour, by another (the bosses/voodoo masters). As Peter Dendle says, zombification is the logical conclusion of human reductionism; it is to reduce a person to a body, to reduce behavior to basic motor functions and to reduce social utility to raw labour. It is the displacement of one’s right to experience life, spirit, passion, autonomy, and creativity for another person’s exploitative gain.

During the ‘30s and ‘40s, the zombie also served as a parable for the plight of women in patriarchal society. Zombie movies consistently depicted undead, zombified women who were subservient to a domineering male [I Walked with a Zombie, 1943]

In the ‘50s, zombies are taken away from “exotic” landscapes and find a home in middle class America. The zombies are mindless victims of an unseen external force that forces everyday people to turn on each other [Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1956]. Many readings of these films suggest a clear relationship to the looming threat of a communist invasion, essentially rendering American individualism into a mindless hoard of red zombies. But it also marks the first time that the zombies became a threat to American society, assuming their role as the dangerous “other.” This is the continued essence of the zombie to this day.

Zombies are a significant symbol in popular culture. As cultural objects, they reveal and reflect their social context through their position as the other. Anything “otherized”— feared, marginalized, or repressed—will find its way into the construction of zombies. Zombies are a barometer of which we can use to observe the collective anxieties and fears of any period or society.

This brings us to Romero’s zombie in Night of the Living Dead, the film that transformed zombies into cannibalistic ghouls that travel in hordes and turn innocent people into their kind.

Romero shot Night of the Living Dead on a small budget with the cheapest film possible: black and white 33m film. The idea came from a short story Romero wrote in college called “Anubis,” which he called an “allegory about what happens when a new society—in this case hordes of the living dead hungry for human flesh—replaces the old order.” Another economical factor was the decision to film at an abandoned farm house in Evans City, Pennsylvania.

Over two hundred and fifty extras were cast as zombies; they used chocolate Bosco syrup for blood and mortician’s wax for the decaying flesh wounds on the zombies. One of the extras owned a meat shop, and he gave Romero pounds of meat and innards to use as human guts. The scenes where the zombies feed on human flesh look so realistic because the extras were actually eating animal innards.

Romero’s zombies can be read in many ways, but the focus of the film has much more to do with how living humans react to a society on the verge of collapse. Its temporal urgency has both a narrative function and a psychological function; it takes place in the span of one day, giving it a true-to-life feel and a terrifying warning of just how quickly we can be engulfed by disaster. Romero’s conception of a contagious, cannibalistic zombie horde uniquely manifests modern apprehensions about the horrors of the Vietnam War, the struggles of the civil rights movement, and a questioning of patriotic American exceptionalism. The first scene at the graveyard has a fluttering American flag in the foreground, which represents the meaningless of patriotism as a moral compass at a time of social decay.

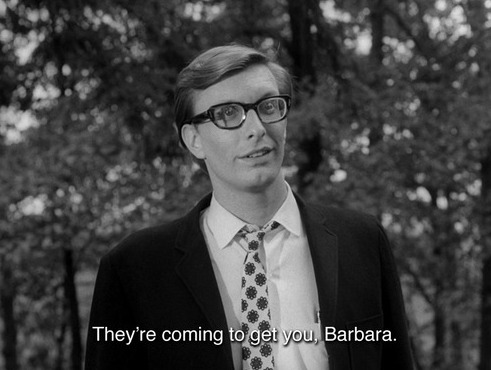

Only two minutes into the film, Romero introduces audiences to the new American zombie. Almost immediately after the infamous line: “they’re coming to get you Barbara,” a lone zombie appears in the graveyard and kills the protagonist Barbara’s brother Johnny. As we find out with this swift, senseless killing, the zombies cannot be reasoned with or dissuaded by logical discourse. The rationalized, civilized “morals” of America are not enough to suppress a full blown epidemic.

Just as the early enslaved zombie resonated with recession-era America, the infected decaying zombie struck a chord with Vietnam-era America. Graphic images of death and decay by photojournalists were surfacing, and the senselessness of war was stirring anger and hopelessness. Romero suggests the destruction of America is brought on by its own ruthless ventures, and it cannot be sustained by its faulty moralizing and patriotism. The dog eat dog nature of survival apocalypse is not a dismal diagnoses of human nature, but a forecast of how Americans will be left scrambling to rationalize their own survival as their moral code is rendered useless.

Romero is justifiably pessimistic in his vision of America under crisis. He suggests, and rightly so, that on the verge of collapse, the lack of solidarity caused by an alienating system rife with racism and misogyny is the ultimate damnation of humankind.

In 1964, after Kennedy was shot, president Lyndon B. Johnson declared that he would make the United Sates into a “great society,” where racial injustice and poverty had no place. But the civil rights act and the voting rights act did little to erase racism and poverty, and the Vietnam War raged on, plucking working-class blacks and whites from their communities and sending them off to die. Mass dissatisfaction — and the realization that “the great society” was nothing more than an empty echo — gave way to the radical anti-war movements and the black power movements. Still, Americans were divided on how to fix the crises their country was facing. What they did know, however, was that something was horrifically wrong.

If only the living could work together, it seems that the zombies would be easy to control. But the living can’t work together, Romero suggests. In Bowling Alone (a book I will frequently mention in my blogs), Robert Putnam notes that the proportion of Americans saying that most people can be trusted fell by more than a third between the 60s and the 90s. This was also a time when the nuclear family was turning inwards to an isolated unit preoccupied with post-war consumption.

By 1965, a majority of Americans made their homes in suburbs rather than cities. And through their greater access to home mortgages, credit, and tax advantages, men benefitted over women, whites over blacks, and middle-class Americans over working-class ones. White Americans more easily qualified for mortgages through discriminatory banking institutions, and more readily found suburban houses to buy than African Americans could.

As a result, a metropolitan landscape emerged where whole communities were increasingly being stratified along class and racial lines, while simultaneously, mass consumption was becoming commonplace in American society. Business leaders, the government, and advertisements and mass media were eager to convince Americans that mass consumption was not a personal indulgence, but a civic responsibility that was tied to standard of living.

In Night of the Living Dead, the house is no longer a home, but a site of entrapment and a prison—objects like the radio are no longer for entertainment, they are for survival. Doors, a symbolic device of many Hollywood films, are used as barricades on the windows. And just as objects are scrutinized for their utility (which can be read as a critique of the rising consumerism of post-war America) humans are reduced to their functionality and self-interest.

Gender roles and the subservience of women seems to only doom the people in the house even further. Barbara is reduced to a docile couch-ridden mute, and Helen Cooper has little say in her husband’s destructive decisions. Barbara’s clear lack of distrust for Ben (illustrated in the scene where she stares ambiguously at the knife) is also a hindrance on their mutual survival.

Romero also takes a jab at the insular nuclear family as an institution that cannot survive, and he illustrates this with the scene in which the young daughter eats her parents (Harry and Helen Cooper). In most horror films, the family is usually the prevailing site of the restoration of order, but Romero blatantly rejects the bourgeois notion of family as a site of mutual respect and meaningful existence.

And through the deaths of Barbara and her brother Johnny, we learn that being altruistic and good offers little redemption. Both characters die in their attempts to help another person. Individual acts of goodness, as well-meaning as possible, do little to save humanity. The character Ben (not quite Hollywood’s idea of “the good black man”) despite his noble actions, still meets his demise at the refusal of the white men to cooperate with him. In the scene where Ben first meets Harry Cooper, a middle-aged white man who is hiding his family in the cellar, Ben and Cooper argue over whether the cellar is the safest place in the house. Cooper insists the cellar is the safest place, while Ben argues that it is a death trap. The two men never reach a consensus, and this tension reflects the very real lack of consensus with Americans on how to address the political and economic crises of the ‘60s. A young black man, who simply wants to survive a crisis, arguing with an older white man is a perfect cinematic snapshot of racial tensions in the United States. The tension eventually blows up when Ben shoots Cooper.

When Ben recounts his first encounter with the zombies, the manner in which he reminisces about the situation evokes a pain that is clearly very real with the actor Duane Jones, and can draw a parable to the racist mob riots and even the violent police reaction to anti-war riots and civil rights riots of the ‘60s—especially the Watts riot in 1965, where 34 people were killed after the California National Guard was called in to quell the riots.

The emotional reminiscence of Ben casts a solemn mood and leaves room for reflection of the horrific state of American society. Romero prompts audiences to think of how America can continue to exist as it is, especially during wartime as it campaigns as the champion of the free world. The characters on screen undoubtedly feel this sense of doom.

Jones’ performance as Ben quickly draws in the audience’s sympathy. The look on Ben’s face immediately after he shoots Cooper quickly changes from satisfaction to pained. This self-realization encapsulates the major theme—the zombies are not the enemy; rather, the people have become their own enemies. With a lack of solidarity, there is no plausible way for humanity to survive the crisis. In the end, when Ben emerges from the dark cellar as the lone survivor, he is shot point blank by a posse of gun-toting vigilante rednecks. Following Ben’s death is a montage of still frames of Ben’s body being dragged by meat hooks into a pile of bodies that are light on fire—a scene reminiscent of the lynchings and racist violence of the Jim Crow era.

By this point, it is clear who the real monsters are. Unlike most horror films, there is no return to order. Order was disrupted almost immediately at the beginning of the film, and the audience does not get to see that same sense of order returned. On a superficial level, order is restored by the men who shoot and kill Ben, but the audience knows that this order has been achieved at the cost of an innocent man’s life.

The return to order in apocalyptic horror films, or any horror film, suggests a major obsession with the need to be constantly reassured about the strength of the status quo. For a while, horror films in the ‘40s and ‘50s had to have an ending that indicated a restoration of order. But a progressive director can suggest the fragility of the status quo. And this is exactly what Romero does.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to this blog

Hi! The “official” title of this blog is Daughter of Horror. :)

This blog will focus on American Horror Films starting from 1960 to the present, and with the exception of Night of the Living Dead, I will be writing in chronological order. I will not rate the films; the point of my blog is to explore and discuss how each film was influenced by popular culture, social issues, historical events, and the predominant fears and anxieties of the time.

I strongly believe that horror as a genre is progressive. Horror films force viewers to confront collective anxieties and [even if only temporarily] identify with transgression and subversion of the dominant ideology. Of course, there are still plenty of reactionary horror films, and I will be talking about them as well (Shivers and Fright Night are two prime examples).

About Me:

My name is Mary and I’m a 23 year old student in Toronto, Canada. Currently I’m majoring in professional writing with a minor in film studies. I will likely be specializing in Soviet Cinema for my master’s degree, but I’d still like to continue my research in the horror genre and hopefully publish a book that follows a similar theme as this blog. I’m also a Marxist, so when I am reading and critiquing a film I am often writing from a Marxist perspective.

Future Reviews:

Here is the order in which I will be posting. I’d like to post once every two weeks, but it may take me longer to compile research on certain films and/or directors. I may also post sooner than biweekly depending on the film.

My first post [on George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead] will be up by the last week of April.

If you have any suggestions, don’t hesitate to message me! I also appreciate feedback, criticism, and discussion.

Note: Some of these films are *not* american, but I will discuss why I believe they are still relevant to American society.

13 Ghosts (1960) dir. William Castle

Homicidal (1961) dir. William Castle

Carnival of Souls (1962) dir. Herk Harvey

The Birds (1963) dir. Alfred Hitchcock

Strait-Jacket (1964) dir. William Castle

Die, Monster, Die! (1965) dir. Daniel Haller

Picture Mommy Dead (1966) dir. Bert I. Gordon

Chamber of Horrors (1966) dir. Hy Averback

Something Weird (1967) dir. Herschell Gordon Lewis

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) dir. Roman Polanski

Satan’s Sadists (1969) dir. Al Adamson

House of Dark Shadows (1970) dir. Dan Curtis

The Wizard of Gore (1970) dir. Herschell Gordon Lewis

Blood and Lace (1971) dir. Philip S. Gilber

The Last House on the Left (1972) dir. Wes Craven

The Exorcist (1973) dir. William Friedkin

The Crazies (1973) dir. George A. Romero

It’s Alive! (1974) dir. Larry Cohen

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) dir. Tobe Hooper

Jaws (1975) dir. Steven Spielberg

Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) dir. Pier Paolo Pasolini

Shivers (1975) dir. David Cronenberg

Carrie (1976) dir. Brian De Palma

The Omen (1976) dir. Richard Donner

The Hills Have Eyes (1977) dir. Wes Craven

Dawn of the Dead (1978) dir. George A. Romero

I Spit on Your Grave (1978) dir. Meir Zarchi

Martin (1978) dir. George A. Romero

The Amityville Horror (1979) dir. Stuart Rosenberg

The Brood (1979) dir. David Cronenberg

Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) dir. Werner Herzog

When a Stranger Calls (1979) dir. Fred Walton

Cannibal Holocaust (1980) dir. Ruggero Deodato

The Fog (1980) dir. John Carpenter

Friday the 13th (1980) dir. Sean S. Cunningham

The Shining (1980) dir. Stanley Kubrick

The Evil Dead (1981) dir. Sam Raimi

Possession (1981) dir. Andrzej Żuławski

Poltergeist (1982) dir. Tobe Hooper

The Thing (1982) dir. John Carpenter

Christine (1983) dir. John Carpenter

Sleepaway Camp (1983) dir. Robert Hiltzik

Videodrome (1983) dir. David Cronenberg

Children of the Corn (1984) dir. Fritz Kiersch

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) dir. Wes Craven

Fright Night (1985) dir. Tom Holland

Day of the Dead (1985) dir. George A. Romero

The Fly (1986) dir. David Cronenberg

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) dir. John McNaughton

Hellraiser (1987) dir. Clive Barker

The Stepfather (1987) dir. Joseph Ruben

Child’s Play (1988) dir. Tom Holland

Dead Ringers (1988) dir. David Cronenberg

The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) dir. Wes Craven

Pet Sematary (1989) dir. Mary Lambert

Flatliners (1990) dir. Joel Schumacher

Misery (1990) dir. Rob Reiner

The People Under the Stairs (1991) dir. Wes Craven

Candyman (1992) dir. Bernard Rose

The Blair Witch Project (1999) dir. Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sanchez

Ginger Snaps (2000) dir. John Fawcett

Uzumaki (2000) dir. Akihiro Higuchi

Cabin Fever (2002) dir. Eli Roth

They (2002) dir. Robert Harmon

High Tension (2003) dir. Alexandre Aja

The Village (2004) dir. M. Night Shyamalan

They (2002) dir. Robert Harmon

Land of the dead (2005) dir. George A. Romero

The Devil’s Rejects (2005) dir. Rob Zombie

Hostel (2005) dir. Eli Roth

30 Days of Night (2007) dir. David Slade

Let the Right One In (2008) dir. Tomas Alfredson

Martyrs (2008) dir. Pascal Laugier

The Human Centipede (First Sequence) (2009) dir. Tom Six

Jennifer’s Body (2009) dir. Karyn Kusama

Rubber (2010) dir. Quentin Dupieux

V/H/S (2012) dir. Adam Wingard, David Bruckner, Ti West, Glenn McQuaid, Joe Swanberg, Radio Silence.

Evil Dead (2013) dir. Fede Álvarez

V/H/S/2 (2013) dir. Jason Eisener, Gareth Evans, Timo Tjahjanto, Eduardo Sánchez, Gregg Hale, Simon Barrett, Adam Wingard

As Above, So Below (2014) dir. John Erick Dowdle

The Witch (2015) dir. Robert Eggers

1 note

·

View note