Text

Reference list

Primary literature:

Jansson, Tove, Bildhuggarens dotter

Jansson, Tove, Midsummer Madness

Jansson, Tove, Moominvalley Midwinter

Jansson, Tove Moominvalley in November

Jansson, Tove Moominpappa at sea

Secondary Literature:

Happonen, Sirke, Den dansande mumindalen, Spralliga språng och existentiellt rörelsespråk. I litteraturens underland. Festskrift till Boel Westin. Maria Andersson & Elina Druker (red.) , 2011, 397-403

Jaques, Zoe, Tiny dots of cold green. Pastoral nostalgia and the state of nature in Tove Jansson’s The Moomins and the Great Flood, In The Lion and the Unicorn Maria Nikolajeva (red.), 2014, 200-216

Laity, K. A. Roses, Beads and Bones. Gender, Borders and Slippage in Tove Jansson’s Moomin Comic Strips, in Tove Jansson Rediscovered Kate McLoughlin och Malin Lindström Brock 2007 Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 166-183.

Sundmark, Björn, Tove Janssons tecknade serie “Muminfamiljen och havet” (1957). En medieanalys, i Historiska och Litteraturhistoriska studier 89 Jannika Tylin- Klaus och Julia Tidigs (red.) 2014, 15-36.

Westin, Boel, Stenens berättelser. Tove Jansson och idén om den lömska barnboksförfattaren, Historiska och Litteraturhistoriska studier 89 Jannika Tylin- Klaus och Julia Tidigs (red.), 55-62.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The end of the journey

Our beautiful journey has finally come to its end. I thank all of you for having read my posts, and I hope this blog made you wanted to dig a bit more into Tove Jansson’s works and life.

This is what has happened with me; starting the course at my University I knew basic information regarding this amazing artist, and I mainly knew her thanks to Moomin. I am so happy to have had the chance of reading different texts and articles about her, because they really helped in widening my comprehension and understanding of her.

I think that the most fascinating aspect regarding Tove Jansson is her capacity of mixing real life events with fantasy, creating a product which is perfectly reliable and relatable. From now on I will read Jansson’s works with more aware eyes, trying to catch their real essence.

This is a goodbye for now, but do not feel sad: if you are still longing for adventure, Tove’s books are out there, ready to be browsed.

What are you waiting for?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back to the origins

Our journey in the hidden secrets of Moominvalley has almost come to an end, and I thought that the best way of concluding a circle would be going back to the origin: Tove. We have to thank her for having shared with us her art and thoughts. She touches a series of thematic with delicate hand and hides them in a form enjoyable by children and adults, which will catch her allusions. It is also necessary to make “justice” for Tove, so that she will not only be remembered as the creator of Moomin, a children’s series.

As Boel Westin (“Stenens berättelser. Tove Jansson och idén om den lömska barnboksförfattaren, Historiska och Litteraturhistoriska studier 89 Jannika Tylin- Klaus och Julia Tidigs (red.), 55-62) states, Tove, by writing children’s literature, was fulfilling a liberation process to purify herself. She writes about families, obsession, loss, dreams, searching for identities, desires and passion. And as herself stated, maybe it is due to all these elements that children's literature does not contain themes for children. We surely agree that her art and literature extended far over the label of children’s literature. She gradually makes Moomin, her alter ego, to disappears, only to come back as the new narrator Toft in Moominvalley in November, lonely soul who is looking for the vanished Family.

Tove wrote the stories related to Moominvalley in peaceful years, after the horrors of World War II, which is somehow present in the stories as a threatening natural force. Tove wrote about a family living in a cheerful valley, where adventures are the order of the day. However, families were changing, and so were the times. It is interesting to notice that Moominvalley in November and Bildhuggarens Dotter have been published on the same year: Westin states how Tove decided to do this in order to put “the children’s book behind her to be the sneaky writer without prefixes” (61).

Tove Jansson was an incredible artist, which was able to touch different themes and thematic with such a unique style that we keep recognize her works without doubt still nowadays. And I am not just talking about the Moomins; one just knows when an illustration was drawn by her hand.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

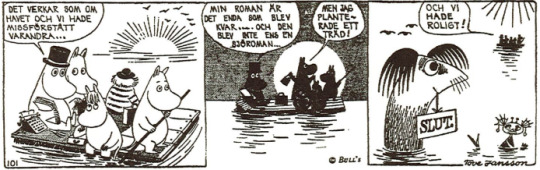

Comic strips

In one of my previous posts, I had already mentioned the concept of iconotext. I'm sure that all my readers are careful, but I will anyway refresh a little the memory of those who are a bit more distracted. An iconotext is a text that features both a verbal part and a picture. The two parts interact, and the reader has to handle the whole time both systems. An inconotext can be just a page or could be about how an entire work interoperate in image and writing.

Tove Jansson's comic strips are indeed an iconotext. They are built through a sequence of rectangular panels which subsequentially brings on the narration in a chronological order. I think that this works is one of the most interesting productions by Jansson. They function as an arena in which she could display adults’ contents in a funny and ironic tone, without forgetting to add deeper considerations on serious topics.

Tove creates her comic strips by repeating a motif through the panels; the motif remains the same, but she changes elements on the way, dragging the reader into confusion and uncertainty (if you are interested to discover more about this aspect, take a look at Laity, K. A. “Roses, Beads and Bones. Gender, Borders and Slippage in Tove Jansson’s Moomin Comic Strips”, in Tove Jansson Rediscovered Kate McLoughlin and Malin Lindström Brock 2007 Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 166-183).

Björn Sundmark (“Tove Janssons tecknade serie “Muminfamiljen och havet” (1957). En medieanalys, in Historiska och Litteraturhistoriska studier 89 Jannika Tylin- Klaus och Julia Tidigs (red.) 2014, 15-36) analyses the comic strips “Moominfamily at sea” Does this title ring a bell? It would be strange if it did not, but you would be surprised to see how different this comic strip is in comparison to the book Moominpappa at sea. In fact, Sundmark explains how bright and expressive the panels are and how rapidly the story evolves. Compared to Moominapppa at sea, where the general feeling is dark and every character is focused on its individual project, the comic strip highlights a sense of community and group. In fact, the atmosphere is more idyllic, and it conveys a sense of adventure. The motifs keep the story together and rewards the expectations of the faithful reader. The stories are mainly based on dialogue, but we also read each character’s comment. Both the comic and the book work perfectly, they are just a bit different. The sea is calmer and harmless and Moominamma’s incorrigible positivity has the last word in the comic strip.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Moominmamma: heart of the narrative

Today’s post will be dedicated to Moominmamma. You are probably familiar with her character, which represents the prototypical idea of motherhood. She is always kind, has everything tidied up and loves to spend time with her family. Tove had confirmed that this character was inspired by her own mother, Signe Hammarsten. In fact, the fictional character and Signe share several traits of their personalities: both are creative, gentle, and are extremely talented at drawing.

Just like what Signe represented in real life for Tove, that is the centre of the family, Moominmamma has the same role in the Moomin family. However, in Moominpappa at sea, Moominamma faces a crisis. In the book, which could be considered the darkest of the Moomin series, both parental figures face difficulties: Moominpappa due to his feeling of being unnecessary, and Moominmamma for the difficulties encountered in the new environment.

After having moved to a lonely island to support Moominpappa’s desire of adventure, Moominmamma starts feeling anxious and wants to go home, being unable to find her place on the new home. To bypass the crisis, she paints small flowers on the windows of the lighthouse which stands there, together with trees on the internal wall. The painting suddenly opens and allow her to enter it. Elina Drunker (Staging the Illusive: Self-Reflective Images in Tove Jansson’s Novels, 2009) makes an interesting consideration. She claims that the scene is a variation of the Chinese myth of an artist that wanders into his own paintings. According to the author, the choice made by Moominamma to recreate her beloved garden is significant, because she choses a familiar and controlled setting in which seeking reparation. Drunker also states that Moominmamma’s art offers her a quiet place to stay, while Moominpappa needs approval from everyone for everything he does.

If you looked at my post related to Tove’s biography and maybe read Bildhuggarens Dotter, you will have noticed the resemblance with the description given by Jansson herself when she talks about her parents’ different approach to art. While her father needed that inspiration came to him in solitude, her mother quietly drew her illustrations without too many ceremonies, and inspiration arrived to her at the right time. It is like what happens here: Moominammma manages to find a place where to repair herself and have a bit of peace, a place where she is the only one who can access. Her prohibition to let others paint on the wall is a sign of female empowerment and, as she gains confidence in her paintings, she starts painting little versions of herself, among whom she can hide. When she is in her painting, she is safe from the hostile island but, at the same time, she can watch her family going on living from a external perspective. Moominmamma finds strength in her solitude, and this strength is visually reinforced by the colourful palette she uses. Moominamma reflects her emotions and hopes through the paintings of the lighthouse, creating a shield where she can go and rest.

While reading both Bildhuggarens Dotter and the Moomin series I was very moved by the maternal figure Tove portrays on her works. Both Moominammma and Signe appear quiet and unceasing, ready to help the others in any time and always willing to follow their partners in any decision. Signe was a model for Tove, both from a personal and artistic point of view. In the same way, Moominmamma is a model for Moomin, and she represents a safe place for him. Even though the father figure may seem a more prominent presence in the stories, is the maternal one that emerges as a winner: calm personalities which hide incredible talents.

0 notes

Text

Nature: ally or enemy?

I have already discussed in a previous post how Tove got inspired by her grandfather’s summer place and the Finnish archipelago to create the setting of the Moomin stories. Nature has then an important role in the stories and is very present throughout the development of the narrative. However, the most careful reader has surely noticed how sometimes nature is hostile towards the characters; if we think about the threat of the comet in Comet in Moominland, the snowy and lonely landscape Moomintroll has to face in Moominland Midwinter, the unfamiliar and dangerous island in Moominpappa at sea we notice how nature becomes a dangerous place for the Moomin family to live in.

As Zoe Jaques (“Tiny Dots of cold green”: pastoral nostalgia and the state of nature in Tove Jansson's The Moomins and the Great Flood, 2014) explains, Tove exposes the Moomins to natural perils, showing how the struggles faced by the characters can also enable a benevolent humanity. Tove Jansson then, did not only limit to celebrate nature, but she also displayed the connection between nature and culture. The author displays how the Moomins seek reparation through their homes against nature: both in Moominsummer madness and The Moomins and the Great Flood they look for a house, and this aspect builds a contrast between the family and nature: nature’s perils can be overcome only through civilization. However, the Moomin’s civilization does not damage nature: they are capable of respecting it and they understand the falsity of technology. For example, when arriving to a mountain inhabited by a gentleman, Moomimamma after first feeling attracted towards the landscapes, immediately understands that all that surrounds her is false. We could also consider this episode as the result of human interference with nature which caused its worsening. Moominmamma then suggests leaving the man’s house and build a real one in real nature. In fact, however dangerous and hostile it might seem, real nature is better that the synthetic one.

Even if apparently paradoxical, the Moomin’s approach is against human comfort; they need a home, but not technology. I would also argue that a home is not a direct equivalent of human comfort. A home gathers members of the same family and conveys an idea of community and love; the Moomins are civilized in this sense, but not in the idea of the exploitation of nature and falsity.

In the end, who needs a jacuzzi if there is nobody to share it with?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dancing Moominvalley

Welcome back to our blog!

Are you enjoying the journey so far? Today we will explore the festive mood of Moominvalley. I am sure that those of you who have read the Moomin series has noticed that the characters living in the iconic valley are quite festive: they often have parties, and they really like to dance in any situation. Have you ever wondered if these celebrations had a meaning or a specific function? As in all Tove’s works, nothing is left to fate in these stories. Let's go and find it out!

Which good party does not have music, and then, dances? The answer is none, and it could be claimed that characters in Moominvalley clearly know how to party. Sirke Happonen (Den dansande Mumindalen – Spralliga språng och existentiellt rörelspråk, in I Litteraturens Underland, feskrift till Boel Westin, Stockholm, 2011), makes an interesting analysis on the function that dances has in the Moomin books. Dance scenes are a strategy that Tove uses to create movement and dynamic in the books and they convey a strong sense of community and playfulness. The dances vivify the images and are a way for the characters to express joyfulness and, at the same time, get free.

Dances are performed more from female characters than from male ones, who anyway participate. The first dance scene in the series is in Comet in Moominland, where small figures dance in couples and the Snorkmaiden seems to be more concerned about dancing than anything else; even the threaten of a comet which may destroy the valley is less important. In the end, if you have to die, why not dance?

The figures dance in different styles: some are characterized by faster movements and dynamic shifts, while others (like Moomin), represent a kind of comic ballerina. Different dance scenes in the books also represent a different relationship between text and image. For example, in Mominvalley in November, Mymble’s dance displays a sense of reluctance at the beginning; her unnatural pose reflects the unnatural situation. In fact, Mymble, Snufkin, the Hemulen, Grandpa-Grumble, Filljyonk and Toft are trying to party at the Moomin’s house, but the situation is artificial due to the absence of the Moomin family. However, Mymble’s dance grows in a crescendo which becomes one of the few lively elements in the stagnant atmosphere of the book. Tove used the expressivity of dances to reinforce the relationship between text and images, creating transcendental movements that involve the reader and invite him/her to dance with the protagonists.

0 notes

Text

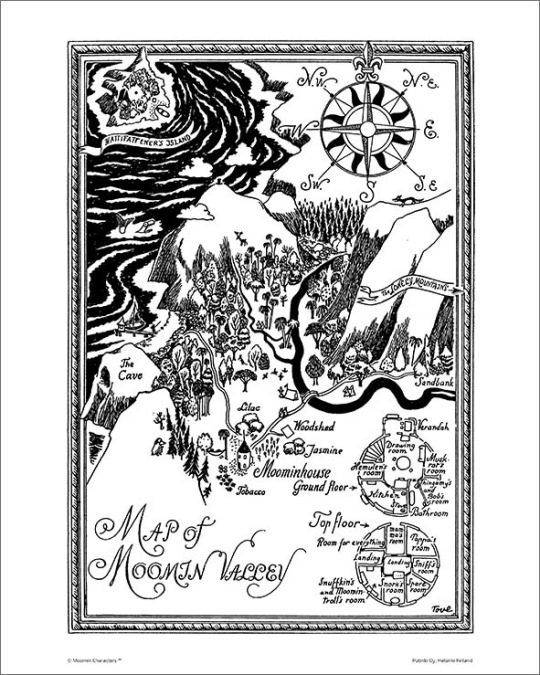

Mapping Moominland

Today's post will help us in getting more familiar with Moominvalley landscapes. The iconic illustrations of the valley are surely one of the most appreciated aspects of the Moomin books. But where do all these beautiful landscapes come from?

Tove Jansson used her lifeas an inspiration for her works. The characters of the Moomin series are based on real people that Tove met in her life. Her country’s landscapes were not an exception; she used the Finnish archipelago and her grandfather’s summer place to create the perfect environment for her stories. I have always thought that maps in the Moomin stories were a bit the beginning of the magic; Tove usually situates them in the book’s first pages, before starting the narration. The maps give information regarding the Moominvalley at the time of the events; even if the place is the same, the maps change in relation to the story.

Björn Sundmark (“A Serious Game”: Mapping Moominland, 2014) gives an interesting analysis related to the role of maps in the Moomin series. He claims that maps do not only systemize a place, but they create an imaginative space. If this consideration is true (and we definitely think it is), maps become an important instrument that has a creative potential. The author then states a question, which seems predictable, but in relation to children's literature becomes essential: what is a map? A map is an iconotext which mixes verbal text, cartography and illustrations. Usually, the verbal text refers to the places' names in the map and the cartographic symbols make the iconotext a map (Sundmark, 2014).

If you have ever read one of the Moomin books, you have certainly noticed the presence of maps in the frontispiece page before the title; Tove shows Moominvalley from a bird’s eye prospective. In the map of Finn Family Moomintroll, the verbal texts are mainly in the description of the house, where Tove explains to whom the rooms own and their functions. But what is the function of maps in Moomin’s books? Firstly, they guide the reader through the places of Moominvalley and help him/her in getting familiar with the environment. Secondly, they communicate specificity and immediateness. More importantly, a map “encapsulates the essence of the narrative, the atmosphere of Moominvalley,” (Sundmark, 2014: 168). The significant characters and important objects are compressed in the map, while actions seem to be happening simultaneously.

One of the aspects that I like the most about these maps is that they function as a summary of the story. Let's take as an example the map of Moominvalley Midwinter: the place is the same as in Finn Family Moomintroll, yet it looks completely different. Everything is in a rounded shape due to the heavy presence of snow and Moomintroll stands alone on the snowy roof of his house. Once again, the map compresses the content of the whole book. I had always looked at the maps in the books, but I had never really thought about the fact that they are so important for the story; the frame they create immediately takes the reader into the story, and the most beautiful part about it, is that you do not even realise it.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's get started: Moomintroll

Here we are back to our blog. As I promised in my introduction, the Moomin series will be a great protagonist of this blog. We have already introduced the figure of Tove Jansson, the incredible mind that gave life to Moominvalley, so now it is time to introduce our second protagonist; Moomintroll! I am sure that most of you know who he is. Rounded, sweet looking, kind and gentle. What if I told you that you would probably not recognise him if you saw his first drawing? Think about the Moomintroll you know now and remove it from your head; the first Moomintroll was a completely different story.

Did you know that Moomintroll’s first appearance was in the satirical magazine Garm? Tove drew many illustrations for it, and initially Moomintroll was her political signature. The ancestor of Moomintroll appeared on the cover page of the October issue 1944, which shows Hitler's plunder in Lapland. Behind the M of Garm, a small white creature pops out, watching concerned the scene. The little character has some resemblance with the famous Moomintroll, but he is thinner, longer and has a pointy nose. We could say that he is the ancestor of the beloved character that only in the 1950’s changed shape into the Moomintroll we know today. The first Moomintroll was simply called Snork, and his sharp-cornered aspect was the reflection of the war years Europe was facing when Tove first illustrated him.

If you are curious to know more about Tove’s contribution to the satirical magazine Garm, you should read Mayumi Tomihara’s “Garm - The people’s watchdog: Tove Jansson and Finland-Swedish culture’s definitive caricature magazine”, which gives a detailed description of the magazine and how different artists, among whom Signe and Tove, contributed to the realization of caricatures that made parody of society and policy. Enriched with illustrations, the book is a good source to get a general overview on Tove’s less known works, that are equally deserving to be discovered. The author also traces the story of Moomintroll’s development, from the little creature mentioned above to the iconic character; because yes, Moomintroll had to climb the ladder of success to get his own show.

Ehm, I mean book(s).

0 notes

Text

Where to start if not from Tove Jansson herself?

It would seem rather odd to open a blog about Tove Jansson and to not give any information about her. So I may say that the best way to explore her life and learn about her is certainly starting from her life.

Jansson wrote an autobiographical book published in 1968, Bildhuggarens Dotter (Sculptor's daughter). The book, divided in twelve chapters, is a collection of memoirs of her childhood. Despite the autobiographical genre, the content of the narrative is written in a rather fictionalized voice, which makes it difficult to distinguish real events from invented ones. Jansson narrates episodes of her life which do not seem connected from a coherent logic, but this fragmented nature of the book gives a good insight on her rather excentric, bohemian family.

My first impression when reading the book was almost as if I was reading a Moomin story. The events she recounts are mixed with magic and fantasy, certainly a very different narration that one would imagine when reading an autobiography. I was firstly confused by her choice of narrating the events in such a imaginative way, but I then realized that maybe she was trying to communicate something else. It was clear that she was not interested in recounting her memories exactly how they had happened, but how she had experienced them as a child. Her fantastic encounters were real; at least, in little Tove's imagination.

Tove deliberately decided to write in this particular way firstly to create drama and make the book more appealing. However, this was not the only reason. Behind the fictional child narrator hides the will of criticize and comment certain traditional ideologies. Maria Antas (Livet i ateljén var ingen fest. Om män som skapar kvinnor i Tove Jansson barndomsskildring Bildhuggaren Dotter, 2014) gives an interesting analysis of Tove's father, Viktor Jansson, who "created" women. It is also interesting to see the cover of the book, where a little girl looks at women's sculptures in an atelier. Maybe a little Tove who is trying to find her place in a sequence of beautiful and classic women?

A figure that certainly stands out in the narration is Signe (Ham), Tove's mother. Signe was a key presence in Tove's life, her artistic inspiration and the real center of the Jansson's family. I will be back to the importance of Signe and the role of Moominmamma in the next posts. For now, it is important to know that it was thanks to Signe that Tove started her career. Indeed, she took her mother's place in 1928 when she designed an illustration for the cover page of the children's journal Lunkentuss; it is also Signe that introduced Tove in Garm, a satirical magazine written in Swedish. Tove had to work hard, and fame did not arrive immediately. She attended the Tekniska school of arts in Stockholm and later in Paris. She grew into an independent artist and she freed herself from the definition of "Sculptor's daughter", just becoming Tove Jansson.

0 notes

Text

Before starting...

Now the blog is ready to be filled up with illustrations and information regarding Tove Jansson. But before coming to that, I would like to introduce you to my work and explain in what it will consist.

I opened this blog to discuss and comment Tove Jansson's literary production as part of the course "Tove Jansson - Text och Kontext" at Åbo Akademi University. During the course I will read primary literature by Tove Jansson, together with scientific essays and academic materials. The purpose of the course is to contextualize Jansson's work in its historical and literary context.

This blog will explore several aspects related to Jansson's life and artistic production. The Moomin series will certainly be a great protagonist of the upcoming posts, but I will accompany you in a new Moomin Valley, and we will discover together the secrets that lie behind Jansson's most well-known character.

Are you ready to start the journey?

2 notes

·

View notes