"When life closes a door, it opens a window. Then zombies climb in and eat you." - Anonymous

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Belladonna got a reboot. I wanted her to still be a redhead... technically but more on the pastel side of things. At a glance she seems non-threatening but she will gladly demolish you ♥

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dude, I'm so tired.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you write a mentor character so that they're wise and intelligent but still humanly realistic in terms of flaws and weaknesses?

I’ve often found most character weaknesses come from the strengths the character already has. To that end, let’s look at strengths a mentor character usually has:

Wisdom. The mentor character is supposed to be wiser, if not smarter, than their student. Wisdom or intelligence comes with a number of flaws. The mentor could be arrogant in their intelligence or their wisdom could be difficult to understand. The mentor’s maturity could turn into patronization and condescension.

Experience. Mentor characters have had time to go everywhere, do anything, and learn everything. They have experience, except now they’re older and they aren’t as sharp or flexible as they were in their golden years. The mentor could have the usual problems of an old person, and personality issues associated with those problems: self-hate because they aren’t at their best and jealousy because some people are at their best.

Pride. The mentor becomes a parent figure for their student. The mentor could take too much pride in their student and believe their student is invincible - and that’s dangerous for a number of reasons. The student might stop trusting their mentor, who puts them in dangerous situations.

Some other traits:

Short-tempered. I think it’s because most mentors tend to be older, but nearly all of them are irascible. You can make this into an anger issue or just something that causes friction between the mentor and others.

Reticent. Mentors like to keep things hidden until the plot demands it’s time for the protagonist to know. People/the student might not trust the mentor because they have so many secrets.

Born in a different time/place. Again with the age, but mentors tend to come from places and eras different than where the protagonist comes from. The age/location gap could cause friction or the mentor could have some beliefs that translate into flaws when dealing with the protagonist.

Doubt. The student is inept at the beginning of their training. If their training progresses and they’re still inept, the mentor might feel doubt about their abilities to teach and/or their student’s ability to learn/become the Chosen One.

To shake things up, you might want to change the mentor’s past, disposition, or life. This will create more flaws and such. Here are some suggestions:

The mentor is the same or similar in age to their student (NO ROMANCE)

The mentor was never formally schooled in anything and sometimes makes things up to appear smart

The mentor has a family/other pressing responsibilities they’re juggling in addition to mentoring the hero

The mentor has multiple students

The Chosen One could be the mentor or their student, but no one knows yet - the mentor takes the student under their wing just in case the inexperienced student is The One

The mentor and the student really don’t get along and part ways a number of times

780 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, I have these two characters that eventually become a couple. How can I make sure they have "chemistry"? I see people talk about that with fictional couples all the time, but I don't really understand what it means or how to pull it off...

Chemistry is when two characters have a strong, authentic, natural connection or attraction to one another. This term is most often used for characters who are romantically involved, since good chemistry usually involves sexual tension, but platonic relationships can have chemistry too.

Here are characteristics of characters who have good chemistry:

Attraction: This doesn’t necessarily mean that the characters are romantically and/or sexually attracted to one another, but it can. This means that characters naturally gravitated toward one another and that they are attracted to the other person’s mere existence.

Complement: These characters complement each other. Both are whole on their own (and should be developed that way), but when together they create a new kind of force. They work well together and other people see that. It’s like when two people are always known as a “package”. Everyone refers to them as being together because they’re always together and when they’re together, they seem more complete and balanced to other people.

Connection: Something connects these two characters. It could be because they share a back story, they live near each other, they have a similar hobby, they work at the same place, they’re both in school, or because they keep ending up in the same place at the same time.

Sexual Tension: Sexual tension is most often found when the characters are supposed to be romantically involved, but romance doesn’t have to happen if sexual tension occurs.

Authentic: When characters have good chemistry, their interactions are natural and authentic. This is difficult to pull off because it’s one of those things that just happens when you write.

Reaction: It’s called character chemistry for a reason! Think of characters like elements. Putting the right elements together creates a reaction. These characters need to fit together and their bond needs to create something new.

The Secret Formula: While there are certain characteristics that create chemistry between characters, it all depends on the characters themselves and how you write it. There’s no equation for creating chemistry that will always be successful. Sometimes chemistry between characters comes out naturally without the author’s intention.

Examples of Chemistry in TV Shows

2K notes

·

View notes

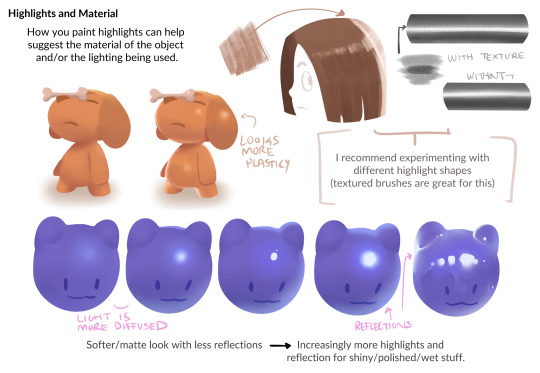

Photo

HEYY my 2nd color tips pdf is now available ! ^o^ hope you enjoy!

BUY HERE or HERE

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

Third Person Omniscient

A step away from the more common “limited” viewpoint, omniscience places the narrator in a position of all-knowing and all-seeing power. The narration can easily jump from MC Martha to Love Interest Lucy to George the Cashier, within the same chapter and often without page breaks. As readers, we can effectively see things from the point of best perspective or the point of best action, even if the best perspective is a bird flying overhead or Generic Soldier #1. Not every character will get a complete arc, but each head you get inside should still have a distinctive personality. It’s a hard line to balance, since you’ve got the narrative voice on top of a unique character voice. It’s not difficult to give a unique voice to your main characters, but not every generic onlooker should sound the same, either.

The perspective allows you to follow the action. If Martha gets knocked out, instead of time jumping to when she wakes up, you can shift into Lucy’s head for a bit. You’re not even limited to the main characters—you can easily get into the villain’s head and let us know what they have planned. This can, however, make it hard to give a good plot twist. This will usually shift your story’s focus to not be on the twist itself, but how they deal with the results.

The narrator might foreshadow upcoming events, either of importance or not. It adds a level of dramatic irony (where you know more than the characters). And really, be careful just to hint. The narrator might already know how things end, but you don’t want to give things away if it’s important.

Often the narrator has its own voice. Many times when I see 3rd person omniscient narrators, they use their all-seeing powers to pop into the heads of random characters as an opportunity for comic relief. They might make fun of characters, or offer their own opinions on the events. The characters have no idea that this all-seeing narrator is following their thoughts and actions, so again, dramatic irony.

The perspective allows characters to inspect each other, which makes relationships and possible relationships less suspenseful. Instead of being stuck in Martha’s head the entire time, wondering if Lucy likes her or not, the narrator can very easily switch to Lucy and give an insight about her feelings towards Martha. 3rd person omniscient is very common in romance novels for this reason. It ups the tension knowing they both like each other, but neither will admit it. The tension comes in their personal struggle to act or not act on their desires.

Examples of sentences you might read in third person omniscient:

A woman across the street saw the teenager disappear into the wormhole, but paused only a minute. She blinked. A trick of the eyes, she decided. Besides, she was already late for work.

Grug the goblin scurried away to do his master’s command, pleased that his expertise would finally be recognized. He’d get a promotion for this—all he had to do was kill some overrated girl with a sword. But Grug had a lot to learn about girls with swords.

Genres typically told in this tense:

High Fantasy, especially when there is an emphasis on fight scenes. Each fighter can react and size up the other’s movements, and appreciate each other’s skills. (The Legend of Drizzt series by RA Salvatore)

Romance. Like stated before, there’s tension in knowing what each side wants, and then knowing why they won’t act on it. Plus, romances generally cater towards a female audience. This POV allows readers into the more familiar woman’s perspective as well as the man’s romantic thoughts towards her. You can read all the romantic things your man never says out loud, but still thinks about!

Anything can be told in this POV, but make sure there’s a reason for it. Since the default storytelling mode is 3rd person limited, there should be purpose in straying from that.

If you want to write in this perspective, read plenty of books written in it. Here are a handful of book recommendations in 3rd person omniscient to get your started: Downsiders by Neal Shusterman, Artemis Fowl by Eoin Colfer, The Legend of Drizzt series by RA Salvatore. The first two link to book reviews with a creative writing analysis, both of which talk more about the narrative voice and ways to successfully implement a 3rd person omniscient narrative.

An overview of the other points of view.

—E

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

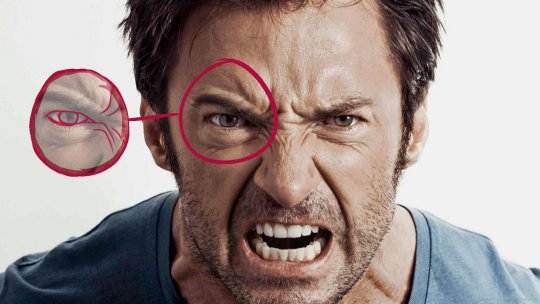

Tiny trick I use when I draw “growly” expressions is starting the lines at the tear duct It doesnt always start there but when simplifying art that’s the method I do!

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Help

I redid this list because broken links 💀

General Tips

Stretch your fingers and hands

Art is for fun

Never too late to start/improve

Using a tablet

Editing software: pictures & video

Moodboard resources

Comic pacing

Watercolor

Coloring

Color Theory (not children's hospital)

Gold

Dark Skin undertones

Dark Skin in pastel art

POC Blush tones

Eyes colors

Human Anatomy

POSE REFERENCES

Wizard Battle poses

Shoulders

Tips for practicing anatomy

Proportional Limbs

Skeletons

Hair Directions

Afro, 4C hair

Clothing

Long skirts

Traditional Chinese Hanfu (clothing reference)

CLOTHING REFERENCE

Sewing information

Animals

Horse -> Dragon

Snouts: dogs, cats, wolves, fox

Foot, paw, hoof

More

Drawing references sources

Art tutorial Masterlist

Another art tutorial Masterlist

Inspiration: father recreates son's art

Inspiration: Lights

ART BOOKS

Plants/flowers: North America, Hawaii, Patagonia

47K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Layer Effects Tutorial by Robin

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cliché

A cliché is NOT a trope.

A trope is NOT a cliché.

Tropes are things that are used over and over again. They’re conventional actions, people (archetypes), and things, that make up story the same way rhyming schemes and set meter make up poetry. Tropes aren’t bad. They’re a tool.

Cliché’s are thoughtless generic place holders. They’re frequently the first thought to occur you precisely because you’ve seen it so often. But the Clichéness is in the (lack of) thought, not the frequency.

When you worry that you are going to be cliché, what you’re worried about is that you haven’t thought enough about your story. You’ve taken the first thought that occurred to you and just taken it. Sometimes that’s good, that’s your storyteller instinct. But particularly at the beginning it’s easy to simply take your first thought because you don’t want to think any more about it. So, yes, you do tend to use tropes, and you tend to use the one that you have run into the most in a close situation because that’s easiest for your brain. And that’s bad: not the trope, how you used it.

What I’m telling you is that the Trope isn’t the problem. The problem is how much you’ve thought about it. A trope is a tried and true method for solving a story problem. A cliché is a tried and true story method misapplied. It’s the misapplication that is the problem.

My best piece of advice for dealing with cliché is to stop worrying if your method for solving your story’s problem has been done before. It has. And somebody did it before that. And someone else did it before them. But somehow it didn’t screw their story over. Funny that. Why would it inherently screw yours?

Instead worry if what you’ve done solves your story problem the best way that it can be solved for your particular tale. That’s when you’ve beat cliché: when you’ve mastered the extremely difficult art of correct application, which must be relearned for every individual problem. Not when you’ve miraculously mastered the impossibility of saying something new. Worry about your story, not anyone else’s. Of course what’s happening has been done before. But it’s been done right and its been done wrong. The people who did it right, did so by thinking very hard and rejecting anything that could be done better until it was good enough.

If your question is, “I’ve seen this done a million times. Should I….” Stop. It doesn’t matter. If your question is, “Why does this bore me?” Then you’re on the right track. And the answer isn’t just that it has been done before. It’s that it doesn’t work for your story. The answer that does work will have been just as used, it just won’t be the first thing to pop into your head. “What would make this interesting?” “What else could they do?” “What would have more meaning?” Those are the questions to ask yourself. That’s avoiding cliché, not going on a goose hunt just to avoid eating turkey.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Give Your Villain an Emotional Backstory That Isn’t Tragic

In crafting a villain’s backstory, we often want the origin to be as powerful as the character themselves. As Chris Colfe says, “A villain is just a victim whose story hasn’t been told.”

Unfortunately, however, tragic backstories become tedious. Oh, of course their parents were eaten alive in front of them, their home was foreclosed on by a corrupt institution, the love of their life betrayed them, their favorite TV show was canceled, and they couldn’t get the last scrap of mayonnaise out of the jar. Someone get the fainting couch, quick.

At a certain point, it’s no longer a backstory – it’s a sob story, which quickly transforms our empathy into pity, and finally into boredom. We roll our eyes and wish the villain had kept the melodrama to themselves.

On the other side of that coin, having a character who stomps on bunnies for no reason isn’t exactly relatable, and a well-rounded character can’t just burst into existence one day fully formed. Everyone has a history.

So how can you give your villain a backstory that tugs on readers’ heartstrings, without making it a sob story?

For this, we’re going to use Epic of Lilith as an example once again (How to Make Your Villain Domestic but Still Evil), as well as Megamind briefly. Some of these tips can also be applied to heroes, but we’ll stay villain-centric for now.

Keep reading

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

I have some trouble w focusing on my WIP, bc I don't really know how to plot. I know what's the big picture, but I don't know how to put the details, unify the scenes and build the whole story. I feel the plot is quite boring, but I cant nor want change too much cuz then it'll affect the nexts books. It's the story of two friends who have to live far away one of another, and there's a war and they have the chance to met five times before one of them dies. And their lives meanwhile, but idk. Help

It sounds like you have some problems with sub-plots, my friend!

Here are some links that might help!

all about subplots

4 tips to writing subplots

20 basic plots

the mind map method

how to plot a complex novel in one day

a guide to plotting

tips for visual thinkers

p.s.

I know i sucks, but sometimes re-doing the entire plot of your novel is the way to go. If it’s not working, something has to change.

I hope this helps!

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tips On Planning Out A Series

This is also available on wordsnstuffblog.com!

– This is a list of tips I’ve gathered throughout the outlining process of my work in progress. If you are an author, feel free to leave your own tips in the replies!

–Patreon || Ko-Fi || Masterlists || Work In Progress || Studyblr || Studygram

Figure Out What Type Of Series You’re Writing

There are many forms a series can follow, but in the base level world of understanding your series, you should know what type of series you’re going to be writing. Either your series is one of episodic plot, wherein each book is a contained conflict and resolution, but following the same set of characters on a singular timeline, or you’re splitting one big story arc into a series of novels in order to flesh it out in detail and allow enough time for the reader to become invested in the details.

Don’t Stretch It Too Much

If you plan on writing a series, you need to have enough content to justify the amount of time and attention you’re asking of the reader. If your series is going to be seven books long, you need to have seven books worth of content, not two books worth that you spun and twisted and over-elaborated on for the sake of word count. Earn your reader’s loyalty to your story by giving them substance to enjoy, rather than long instances of nothing between short bursts of importance.

Plead Ahead or Edit Diligently

It is imperative that you decide from the beginning whether you’re going to plan your story from start to finish ahead of time, or go with the flow and tear it to shreds later. Whatever you choose is justified and can produce a good product as long as you’re willing to deal with the consequences of that choice. If you choose to plan out six books worth of plot, conflict, world building, and character development ahead of time, be aware that it will be a long while before you actually put pen to paper. If you choose to start somewhere and go and deal with the spill of ideas and possibilities later, then know that you will spend about 10 times as much time editing, rewriting, and re-editing as you spent actually writing. Either way, refinement of detail takes up more time in the writing process than actual writing.

Think About The Reader’s Experience

When you’re thinking about timing, revelations, growth, progression, and foreshadowing, your number one thought should be “how is this going to affect the reader’s experience of my story?”. When you release each book, you are handing it off. You don’t get to explain to each individual reader what you meant by this, or how this is supposed to make them feel, or why you included this cryptic piece of dialogue or this detail at this precise moment. You have to construct your story in a way that unfolds deliberately and effectively. Always put the reader first, and you will gain a loyal, captivated audience.

Twist The Commonalities

If you notice that your story shares a lot of attributes or includes a lot of tropes that you know the reader would recognize, this isn’t a bad thing and won’t be a detriment to your story as long as you make it your own. I don’t know how to state this in a way that isn’t going to start a fight in the comments, but originality is dead so long as you refuse to acknowledge interpretation. Interpret the character archetype or the trope however you feel fits your story and try to make it like nothing you’ve ever seen before. Not only for the sake of avoiding criticism for the use of it, but because new things are more exciting to create than reused things are interesting to copy.

Understand The Voice(s) Of The Series

Some books are told in first person, third person, whatever. That’s important to an extent, but one thing that goes severely overlooked is the decisions you make that contribute to the voice behind the storytelling. The way you tell the story impacts the way the reader experiences it, and things like details that you repeat, preferred vocabulary and phrases, and even where you put commas and em-dashes forms your voice as a writer, and your character’s voice in the case of first person.

Support Wordsnstuff!

FIND MORE ON WORDSNSTUFFBLOG.COM

If you enjoy my blog and wish for it to continue being updated frequently and for me to continue putting my energy toward answering your questions, please consider Buying Me A Coffee, or pledging your support on Patreon.

Request Resources, Tips, Playlists, or Prompt Lists

Instagram // Twitter //Facebook //#wordsnstuff

FAQ //monthly writing challenges // Masterlist

MY CURRENT WORK IN PROGRESS (Check it out, it’s pretty cool. At least I think it is.)

Studyblr || Studygram

Check out my YouTube Channel!

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#reblog#ok but i don't tend to shove personal things into anyone's face but this applies#the crypt is empty

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Need..‼️

912 notes

·

View notes