Photo

A Thoughtful & Spiritual Journey of a Young Man's Experiences as a Civil War Soldier. by Opus Book Review Format: Kindle Edition “I Didn’t Sign Up For This” by author Dr. Don C. Kean is a story about young J.D. Sims. J.D. grows up on a farm in Fishing View, Kentucky in and around the 1850’s. J.D. loves his family and fishing. His father is a simple, hardworking and loving man who as J.D. says, has “walking around smarts”. His mother is equally loving and in J.D.’s opinion, there is no person better to cook up a day’s catch than his mama. They are a family that has a deep connection to God. As J.D is coming of age, there are whispers of a possible war coming to the South and brought about by the North but it is thought that nothing would come of it and as J.D. hears these rumors, he isn’t much bothered by it as it seemed a ridiculous thing to him, a country’s people fighting their own selves. What sense does that make? He asked his Uncle Billy about the Yankees and why would they want to start a war? His Uncle Billy explained that some of the people who lived up North were against black slavery and wanted to change the laws that made it legal. This causes J.D to begin to give quite a bit of thought to the black slaves and what he knew of the subject. The subject becomes a cause of great consternation for J.D. It was with his Uncle Billy and on a trip to Paducah, Kentucky that J.D. comes across what sparks another great love of his life; a map of the United States that he sees on the wall of a general store. It doesn’t take long for J.D. to know this map like the back of his own hand and becomes quite astute in the subject of Geography. As the year 1861 approaches, J.D. is faced with a decision. He can go away to school and this option appeals to him as it would afford him the opportunity to see more of that country he was so fond of looking at on that map of his. He could stay home and work on the farm with his Daddy which would be a fine life, too. Or he could join the other men of the South that were forming the Confederate Army. As he is trying to decide what would be best for him and his family he realized that becoming a man meant that he would often face these types of important decisions. J.D. is a very thoughtful young man. J.D. decides that his honor and the honor of his family would best be served if he were to join the Confederate Army. The opportunity to see the places he only knew from maps seemed an exciting proposition as well. Before J.D leaves his family to go off to the army, his mother presents him with a Bible, one that she had bought prior as a Christmas present but had saved it because she knew that the right time would come for him to receive this gift and that time had come. This gift becomes an intricate part of J.D. Sims life and the story that ensues. I Didn’t Sign Up For this is a story of a young man who becomes greatly conflicted with what is happening in the world around him. The voice of J.D. is a clear and genuine narrative, a great deal of fun to read if you enjoy reading the dialects of the South. It is a book about a person’s thoughts and decisions, how they are in relation with God’s word and the diversion between what is right and what is wrong. A potentially a heavy topic that author Dr. Don C. Kean manages to write in a delightfully entertaining manner. The authors love of fishing shines through his main character, J.D. Sims. If you are a religious person or have a connection with God, you will enjoy this book as it is largely centered around J.D.’s relationship with God and the words he finds in the Bible as he is faced with the moral struggles that are encountered during a contentious period of American history. I admired the characters curious, kind, thoughtful and honorable nature. Dr. Don C Kean D.M.D is a retired General Dentist of 25 years. He is a die hard University of Kentucky Wildcats fan. He is also a fan of automobile racing. His truest passion is freshwater fishing especially at Kentucky Lake which is where the background of this story takes place. He hopes to one day live out his years on Kentucky Lake.

0 notes

Quote

A Thoughtful & Spiritual Journey of a Young Man's Experiences as a Civil War Soldier. by Opus Book Review Format: Kindle Edition “I Didn’t Sign Up For This” by author Dr. Don C. Kean is a story about young J.D. Sims. J.D. grows up on a farm in Fishing View, Kentucky in and around the 1850’s. J.D. loves his family and fishing. His father is a simple, hardworking and loving man who as J.D. says, has “walking around smarts”. His mother is equally loving and in J.D.’s opinion, there is no person better to cook up a day’s catch than his mama. They are a family that has a deep connection to God. As J.D is coming of age, there are whispers of a possible war coming to the South and brought about by the North but it is thought that nothing would come of it and as J.D. hears these rumors, he isn’t much bothered by it as it seemed a ridiculous thing to him, a country’s people fighting their own selves. What sense does that make? He asked his Uncle Billy about the Yankees and why would they want to start a war? His Uncle Billy explained that some of the people who lived up North were against black slavery and wanted to change the laws that made it legal. This causes J.D to begin to give quite a bit of thought to the black slaves and what he knew of the subject. The subject becomes a cause of great consternation for J.D. It was with his Uncle Billy and on a trip to Paducah, Kentucky that J.D. comes across what sparks another great love of his life; a map of the United States that he sees on the wall of a general store. It doesn’t take long for J.D. to know this map like the back of his own hand and becomes quite astute in the subject of Geography. As the year 1861 approaches, J.D. is faced with a decision. He can go away to school and this option appeals to him as it would afford him the opportunity to see more of that country he was so fond of looking at on that map of his. He could stay home and work on the farm with his Daddy which would be a fine life, too. Or he could join the other men of the South that were forming the Confederate Army. As he is trying to decide what would be best for him and his family he realized that becoming a man meant that he would often face these types of important decisions. J.D. is a very thoughtful young man. J.D. decides that his honor and the honor of his family would best be served if he were to join the Confederate Army. The opportunity to see the places he only knew from maps seemed an exciting proposition as well. Before J.D leaves his family to go off to the army, his mother presents him with a Bible, one that she had bought prior as a Christmas present but had saved it because she knew that the right time would come for him to receive this gift and that time had come. This gift becomes an intricate part of J.D. Sims life and the story that ensues. I Didn’t Sign Up For this is a story of a young man who becomes greatly conflicted with what is happening in the world around him. The voice of J.D. is a clear and genuine narrative, a great deal of fun to read if you enjoy reading the dialects of the South. It is a book about a person’s thoughts and decisions, how they are in relation with God’s word and the diversion between what is right and what is wrong. A potentially a heavy topic that author Dr. Don C. Kean manages to write in a delightfully entertaining manner. The authors love of fishing shines through his main character, J.D. Sims. If you are a religious person or have a connection with God, you will enjoy this book as it is largely centered around J.D.’s relationship with God and the words he finds in the Bible as he is faced with the moral struggles that are encountered during a contentious period of American history. I admired the characters curious, kind, thoughtful and honorable nature. Dr. Don C Kean D.M.D is a retired General Dentist of 25 years. He is a die hard University of Kentucky Wildcats fan. He is also a fan of automobile racing. His truest passion is freshwater fishing especially at Kentucky Lake which is where the background of this story takes place. He hopes to one day live out his years on Kentucky Lake.

0 notes

Photo

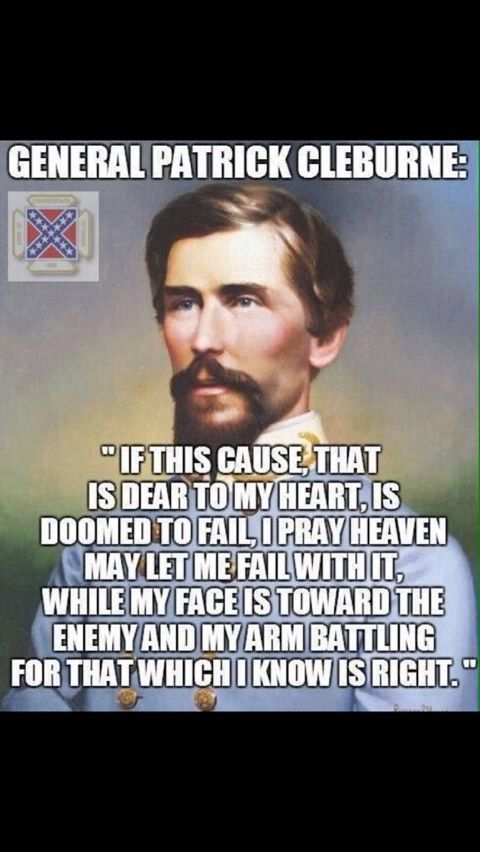

IF THE WORD DUTY WAS EVER PERSONIFIED, Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne was the carrying vessel. Do you admire individuals who carry deep convictions? How about one who exemplified his convictions in action, while also accepting the repercussions both good and bad? Patrick Cleburne's is an intriguing story of an Irish Immigrant who struggled in sheer determination to make his way in life. Cleburne rises through the military ranks as a non West Point Graduate to become a gallant Major General whose men adored him. This is a true story of what hard work and determination can accomplish. Patrick Cleburne was born in Ovens, County Cork, Ireland, on March 16, 1828, at Bride Park Cottage to Joseph Cleburne, a doctor, and Mary Anne Ronayne Cleburne. He was the third child and second son of a Protestant, middle-class family that included 2 brothers and a sister. His mother died when he was eighteen months old His father remarried Isabella Stewart and there were three half-siblings born to this union: Isabella, Robert, and Christopher. At age eight, the family moved to Grange Farm, near Ballincollig. While residing their Cleburne attended Church of Ireland Reverend William Spedding’s boarding school. His father would pass away unexpectedly of typhus in November 1843, having contracted it from a patient. “Ronayne,” as the family called him, was expected to carry on in the family profession of medicine. Cleburne's formative years while a child in Ireland were critical in the formation of a very grim and determined man. 19th century Ireland was a land ruled by feudal landlords who would drive their non rent paying tenants away with the bayonet. He attempted to become a physician and apprenticed for two years in an apothecary. When he failed the entrance exam at Trinity College, Dublin, he could not dare to face his family. Thus he enlisted in the 41st Foot in the British army. He found army life in Dublin to be extremely mundane. For three and a half years, Cleburne was posted at a barracks in famine-stricken Ireland. He served during the turbulent months of the 1848 Young Ireland Rebellion and was promoted to corporal on July 1, 1849. The 1840s were years of extreme political and social unrest in Ireland. The crisis deepened after the Irish potato crop failed in 1846. Relations between landlords and tenant laborers deteriorated quickly. Laborers, who usually paid in potatoes, could not pay their rents. Landlords then demanded cash for rent, but with no crop to sell landlords had no cash. It was a vicious cycle that erupted in widespread violence. Hungry, desperate laborers revolted and some landlords were murdered. Cleburne’s regiment was assigned to assist local police in evicting tenants that could not pay. He found himself in the position of guarding food from his fellow countrymen to protect his own social class and the oppressive English government. The famine continued and thousands died in poverty in their homes, by the roadside and in the streets. It is estimated that up to 500 people died in Cork City per week, Food riots and looting increased. Cleburne returned home to find his own family farm in arrears for six months rent. On September 22, 1849, he paid £20 for his discharge from the army and received his papers. In the space left on the discharge for a statement of character was written, “A good soldier.” Cleburne kept the paper for the rest of his life. Cleburne and his family decided to journey to a new life in America in the decade before The American Civil War. Cleburne loved his new country. His family would split up as job opportunity presented soon after arrival in America. Patrick would eventually land in frontier Helena Arkansas poulation 600. Just months later he learned that two physicians in Helena, Arkansas Hector Grant and Charles Nash needed a druggist to manage their store. Nash told Cleburne they needed a competent prescriptionist who could manage the entire shop. In a month, Cleburne had brought complete order to and become the manager of the Grant and Nash Drugstore. As compensation he received $50 a month, a room in the back of the shop, and meals he took with Dr. Grant. He would eventually through grit and diligence earn his way to become a full partnered small businessman. He then dedicated himself to the study of becoming a lawyer. He would soon after be selected a delegate to the Democratic Convention in 1858. Cleburne never owned slaves and often voiced his opposition to the institution. Yet he strongly valued the right and desire of a section of the country to govern itself. Once the American Civil War begins, Cleburne joins the Confederacy purely out of an adoration and loyalty for a society that accepted him and simply gave him a chance. Much of his philosophy was based on witnessing the Irish fight for independence in his homeland. After enlisting He quoted; "If this [Confederacy] that is so dear to my heart is doomed to fail, I pray heaven may let me fall with it, while my face is toward the enemy and my arm battling for that which I know to be right.” Sadly, that wish would tragically be fulfilled. The Yell Rifles were formed in the state to become part of the First Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Cleburne was elected it's colonel. The First Arkansas was attached to the Army of Tennessee, the main Confederate force in the western theater. Cleburne was promoted to brigadier general in March 1862, and participated in the Battle of Shiloh in April and in the 1862 Kentucky Campaign. At the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30, Cleburne was struck in the face by shrapnel and forced to leave the field. He remained away from the army until his recovery six weeks later, He returned to duty for the Battle of Perryville in October. On December 14, 1862, he was promoted to major general. He then commanded at Stones River. During 1863, Cleburne participated in major battles at Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge. On November 27, 1863, his division made a critical stand at Ringgold Gap, Georgia, while as the rearguard protecting the retreating Confederate army. His scant division of 4,000 men managed to fiercely hold back 15,000 of General Joseph Hooker’s Union troops. Cleburne received a Congressional citation from the Confederate Government for his brilliant performance. On January 2, 1864, Cleburne made his most controversial decision ever. He gathered the corps and division commanders in the Army of Tennessee to present a very radical yet extreemely logical proposal. The Confederacy was unable to fill its ranks due to a lack of manpower. Cleburne's correct yet politically charged "Memorial" was designed with the idea to arm the southern slaves for Confederate military service in exchange for their freedom. It was most thoughtfully and brilliantly crafted. However the proposal was not well received at all. Most knew that it was a political time bomb that would stir great controversy. In fact, Jefferson Davis directed that the proposal be suppressed. It was met with so much controversy that it virtually scuttled any chance of Cleburne's further promotion in the ranks. Here is a copy of the full text: Commanding General, The Corps, Division, Brigade, and Regimental Commanders of the Army of Tennessee General:

Moved by the exigency in which our country is now placed we take the liberty of laying before you, unofficially, our views on the present state of affairs. The subject is so grave, and our views so new, we feel it a duty both to you and the cause that before going further we should submit them for your judgment and receive your suggestions in regard to them We therefore respectfully ask you to give us an expression of your views in the premises. We have now been fighting for nearly three years, have spilled much of our best blood, and lost, consumed, or thrown to the flames an amount of property equal in value to the specie currency of the world. Through some lack in our system the fruits of our struggles and sacrifices have invariably slipped away from us and left us nothing but long lists of dead and mangled. Instead of standing defiantly on the borders of our territory or harassing those of the enemy, we are hemmed in to-day into less than two-thirds of it, and still the enemy menacingly confronts us at every point with superior forces. Our soldiers can see no end to this state of affairs except in our own exhaustion; hence, instead of rising to the occasion, they are sinking into a fatal apathy, growing weary of hardships and slaughters which promise no results. In this state of things it is easy to understand why there is a growing belief that some black catastrophe is not far ahead of us, and that unless some extraordinary change is soon made in our condition we must overtake it. The consequences of this condition are showing themselves more plainly every day; restlessness of morals spreading everywhere, manifesting itself in the army in a growing disregard for private rights; desertion spreading to a class of soldiers it never dared to tamper with before; military commissions sinking in the estimation of the soldier; our supplies failing; our firesides in ruins. If this state continues much longer we must be subjugated. Every man should endeavor to understand the meaning of subjugation before it is too late. We can give but a faint idea when we say it means the loss of all we now hold most sacred — slaves and all other personal property, lands, homesteads, liberty, justice, safety, pride, manhood. It means that the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern school teachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by all the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, our maimed veterans as fit objects for derision. It means the crushing of Southern manhood, the hatred of our former slaves, who will, on a spy system, be our secret police. The conqueror’s policy is to divide the conquered into factions and stir up animosity among them, and in training an army of negroes the North no doubt holds this thought in perspective. We can see three great causes operating to destroy us: First, the inferiority of our armies to those of the enemy in point of numbers; second, the poverty of our single source of supply in comparison with his several sources; third, the fact that slavery, from being one of our chief sources of strength at the commencement of the war, has now become, in a military point of view, one of our chief sources of weakness.

The enemy already opposes us at every point with superior numbers, and is endeavoring to make the preponderance irresistible. President Davis, in his recent message, says the enemy “has recently ordered a large conscription and made a subsequent call for volunteers, to be followed, if ineffectual by a still further draft.” In addition, the President of the United States announces that “he has already in training an army of 100,000 negroes as good as any troops,” and every fresh raid he makes and new slice of territory he wrests from us will add to this force. Every soldier in our army already knows and feels our numerical inferiority to the enemy. Want of men in the field has prevented him from reaping the fruits of his victories, and has prevented him from having the furlough he expected after the last reorganization, and when he turns from the wasting armies in the field to look at the source of supply, he finds nothing in the prospect to encourage him. Our single source of supply is that portion of our white men fit for duty and not now in the ranks. The enemy has three sources of supply: First, his own motley population; secondly, our slaves; and thirdly, Europeans whose hearts are fired into a crusade against us by fictitious pictures of the atrocities of slavery, and who meet no hindrance from their Governments in such enterprise, because these Governments are equally antagonistic to the institution. In touching the third cause, the fact that slavery has become a military weakness, we may rouse prejudice and passion, but the time has come when it would be madness not to look at our danger from every point of view, and to probe it to the bottom. Apart from the assistance that home and foreign prejudice against slavery has given to the North, slavery is a source of great strength to the enemy in a purely military point of view, by supplying him with an army from our granaries; but it is our most vulnerable point, a continued embarrassment, and in some respects an insidious weakness. Wherever slavery is once seriously disturbed, whether by the actual presence or the approach of the enemy, or even by a cavalry raid, the whites can no longer with safety to their property openly sympathize with our cause. The fear of their slaves is continually haunting them, and from silence and apprehension many of these soon learn to wish the war stopped on any terms. The next stage is to take the oath to save property, and they become dead to us, if not open enemies. To prevent raids we are forced to scatter our forces, and are not free to move and strike like the enemy; his vulnerable points are carefully selected and fortified depots. Ours are found in every point where there is a slave to set free. All along the lines slavery is comparatively valueless to us for labor, but of great and increasing worth to the enemy for information. It is an omnipresent spy system, pointing out our valuable men to the enemy, revealing our positions, purposes, and resources, and yet acting so safely and secretly that there is no means to guard against it. Even in the heart of our country, where our hold upon this secret espionage is firmest, it waits but the opening fire of the enemy’s battle line to wake it, like a torpid serpent, into venomous activity.

In view of the state of affairs what does our country propose to do? In the words of President Davis “no effort must be spared to add largely to our effective force as promptly as possible. The sources of supply are to be found in restoring to the army all who are improperly absent, putting an end to substitution, modifying the exemption law, restricting details, and placing in the ranks such of the able-bodied men now employed as wagoners, nurses, cooks, and other employe[e]s, as are doing service for which the negroes may be found competent.” Most of the men improperly absent, together with many of the exempts and men having substitutes, are now without the Confederate lines and cannot be calculated on. If all the exempts capable of bearing arms were enrolled, it will give us the boys below eighteen, the men above forty-five, and those persons who are left at home to meet the wants of the country and the army, but this modification of the exemption law will remove from the fields and manufactories most of the skill that directed agricultural and mechanical labor, and, as stated by the President, “details will have to be made to meet the wants of the country,” thus sending many of the men to be derived from this source back to their homes again. Independently of this, experience proves that striplings and men above conscript age break down and swell the sick lists more than they do the ranks. The portion now in our lines of the class who have substitutes is not on the whole a hopeful element, for the motives that created it must have been stronger than patriotism, and these motives added to what many of them will call breach of faith, will cause some to be not forthcoming, and others to be unwilling and discontented soldiers. The remaining sources mentioned by the President have been so closely pruned in the Army of Tennessee that they will be found not to yield largely. The supply from all these sources, together with what we now have in the field, will exhaust the white race, and though it should greatly exceed expectations and put us on an equality with the enemy, or even give us temporary advantages, still we have no reserve to meet unexpected disaster or to supply a protracted struggle. Like past years, 1864 will diminish our ranks by the casualties of war, and what source of repair is there left us? We therefore see in the recommendations of the President only a temporary expedient, which at the best will leave us twelve months hence in the same predicament we are in now. The President attempts to meet only one of the depressing causes mentioned; for the other two he has proposed no remedy. They remain to generate lack of confidence in our final success, and to keep us moving down hill as heretofore. Adequately to meet the causes which are now threatening ruin to our country, we propose, in addition to a modification of the President’s plans, that we retain in service for the war all troops now in service, and that we immediately commence training a large reserve of the most courageous of our slaves, and further that we guarantee freedom within a reasonable time to every slave in the South who shall remain true to the Confederacy in this war. As between the loss of independence and the loss of slavery, we assume that every patriot will freely give up the latter — give up the negro slave rather than be a slave himself. If we are correct in this assumption it only remains to show how this great national sacrifice is, in all human probabilities, to change the current of success and sweep the invader from our country.

Our country has already some friends in England and France, and there are strong motives to induce these nations to recognize and assist us, but they cannot assist us without helping slavery, and to do this would be in conflict with their policy for the last quarter of a century. England has paid hundreds of millions to emancipate her West India slaves and break up the slave-trade. Could she now consistently spend her treasure to reinstate slavery in this country? But this barrier once removed, the sympathy and the interests of these and other nations will accord with our own, and we may expect from them both moral support and material aid. One thing is certain, as soon as the great sacrifice to independence is made and known in foreign countries there will be a complete change of front in our favor of the sympathies of the world. This measure will deprive the North of the moral and material aid which it now derives from the bitter prejudices with which foreigners view the institution, and its war, if continued, will henceforth be so despicable in their eyes that the source of recruiting will be dried up. It will leave the enemy’s negro army no motive to fight for, and will exhaust the source from which it has been recruited. The idea that it is their special mission to war against slavery has held growing sway over the Northern people for many years, and has at length ripened into an armed and bloody crusade against it. This baleful superstition has so far supplied them with a courage and constancy not their own. It is the most powerful and honestly entertained plank in their war platform. Knock this away and what is left? A bloody ambition for more territory, a pretended veneration for the Union, which one of their own most distinguished orators (Doctor Beecher in his Liverpool speech) openly avowed was only used as a stimulus to stir up the anti-slavery crusade, and lastly the poisonous and selfish interests which are the fungus growth of the war itself. Mankind may fancy it a great duty to destroy slavery, but what interest can mankind have in upholding this remainder of the Northern war platform? Their interests and feelings will be diametrically opposed to it. The measure we propose will strike dead all John Brown fanaticism, and will compel the enemy to draw off altogether or in the eyes of the world to swallow the Declaration of Independence without the sauce and disguise of philanthropy. This delusion of fanaticism at an end, thousands of Northern people will have leisure to look at home and to see the gulf of despotism into which they themselves are rushing.

The measure will at one blow strip the enemy of foreign sympathy and assistance, and transfer them to the South; it will dry up two of his three sources of recruiting; it will take from his negro army the only motive it could have to fight against the South, and will probably cause much of it to desert over to us; it will deprive his cause of the powerful stimulus of fanaticism, and will enable him to see the rock on which his so-called friends are now piloting him. The immediate effect of the emancipation and enrollment of negroes on the military strength of the South would be: To enable us to have armies numerically superior to those of the North, and a reserve of any size we might think necessary; to enable us to take the offensive, move forward, and forage on the enemy. It would open to us in prospective another and almost untouched source of supply, and furnish us with the means of preventing temporary disaster, and carrying on a protracted struggle. It would instantly remove all the vulnerability, embarrassment, and inherent weakness which result from slavery. The approach of the enemy would no longer find every household surrounded by spies; the fear that sealed the master’s lips and the avarice that has, in so many cases, tempted him practically to desert us would alike be removed. There would be no recruits awaiting the enemy with open arms, no complete history of every neighborhood with ready guides, no fear of insurrection in the rear, or anxieties for the fate of loved ones when our armies moved forward. The chronic irritation of hope deferred would be joyfully ended with the negro, and the sympathies of his whole race would be due to his native South. It would restore confidence in an early termination of the war with all its inspiring consequences, and even if contrary to all expectations the enemy should succeed in over-running the South, instead of finding a cheap, ready-made means of holding it down, he would find a common hatred and thirst for vengeance, which would break into acts at every favorable opportunity, would prevent him from settling on our lands, and render the South a very unprofitable conquest. It would remove forever all selfish taint from our cause and place independence above every question of property. The very magnitude of the sacrifice itself, such as no nation has ever voluntarily made before, would appal [sic] our enemies, destroy his spirit and his finances, and fill our hearts with a pride and singleness of purpose which would clothe us with new strength in battle. Apart from all other aspects of the question, the necessity for more fighting men is upon us. We can only get a sufficiency by making the negro share the danger and hardships of the war. If we arm and train him and make him fight for the country in her hour of dire distress, every consideration of principle and policy demand that we should set him and his whole race who side with us free. It is a first principle with mankind that he who offers his life in defense of the State should receive from her in return his freedom and his happiness, and we believe in acknowledgment of this principle. The Constitution of the Southern States has reserved to their respective governments the power to free slaves for meritorious services to the State. It is politic besides. For many years, ever since the agitation of the subject of slavery commenced, the negro has been dreaming of freedom, and his vivid imagination has surrounded that condition with so many gratifications that it has become the paradise of his hopes. To attain it he will tempt dangers and difficulties not exceeded by the bravest soldier in the field. The hope of freedom is perhaps the only moral incentive that can be applied to him in his present condition. It would be preposterous then to expect him to fight against it with any degree of enthusiasm, therefore we must bind him to our cause by no doubtful bonds; we must leave no possible loop-hole for treachery to creep in. The slaves are dangerous now, but armed, trained, and collected in an army they would be a thousand fold more dangerous; therefore when we make soldiers of them we must make free men of them beyond all question, and thus enlist their sympathies also. We can do this more effectually than the North can now do, for we can give the negro not only his own freedom, but that of his wife and child, and can secure it to him in his old home. To do this, we must immediately make his marriage and parental relations sacred in the eyes of the law and forbid their sale. The past legislation of the South concedes that a large free middle class of negro blood, between the master and slave, must sooner or later destroy the institution. If, then, we touch the institution at all, we would do best to make the most of it, and by emancipating the whole race upon reasonable terms, and within such reasonable time as will prepare both races for the change, secure to ourselves all the advantages, and to our enemies all the disadvantages that can arise, both at home and abroad, from such a sacrifice. Satisfy the negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race. Give him as an earnest of our intentions such immediate immunities as will impress him with our sincerity and be in keeping with his new condition, enroll a portion of his class as soldiers of the Confederacy, and we change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.

Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters good stead in battle. In the great sea fight of Lepanto where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom, and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves. The negro slaves of Saint Domingo, fighting for freedom, defeated their white masters and the French troops sent against them. The negro slaves of Jamaica revolted, and under the name of Maroons held the mountains against their masters for 150 years; and the experience of this war has been so far that half-trained negroes have fought as bravely as many other half-trained Yankees. If, contrary to the training of a lifetime, they can be made to face and fight bravely against their former masters, how much more probable is it that with the allurement of a higher reward, and led by those masters, they would submit to discipline and face dangers.

We will briefly notice a few arguments against this course. It is said Republicanism cannot exist without the institution. Even were this true, we prefer any form of government of which the Southern people may have the molding, to one forced upon us by a conqueror. It is said the white man cannot perform agricultural labor in the South. The experience of this army during the heat of summer from Bowling Green, Ky., to Tupelo, Miss., is that the white man is healthier when doing reasonable work in the open field than at any other time. It is said an army of negroes cannot be spared from the fields. A sufficient number of slaves is now administering to luxury alone to supply the place of all we need, and we believe it would be better to take half the able-bodied men off a plantation than to take the one master mind that economically regulated its operations. Leave some of the skill at home and take some of the muscle to fight with. It is said slaves will not work after they are freed. We think necessity and a wise legislation will compel them to labor for a living. It is said it will cause terrible excitement and some disaffection from our cause. Excitement is far preferable to the apathy which now exists, and disaffection will not be among the fighting men. It is said slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties. We have now briefly proposed a plan which we believe will save our country. It may be imperfect, but in all human probability it would give us our independence. No objection ought to outweigh it which is not weightier than independence. If it is worthy of being put in practice it ought to be mooted quickly before the people, and urged earnestly by every man who believes in its efficacy. Negroes will require much training; training will require much time, and there is danger that this concession to common sense may come too late.

P. R. Cleburne, major-general, commanding division D. C. Govan, brigadier-general John E. Murray, colonel, Fifth Arkansas G. F. Baucum, colonel, Eighth Arkansas Peter Snyder, lieutenant-colonel, commanding Sixth and Seventh Arkansas E. Warfield, lieutenant-colonel, Second Arkansas M. P. Lowrey, brigadier-general A. B. Hardcastle, colonel, Thirty-second and Forty-fifth Mississippi F. A. Ashford, major, Sixteenth Alabama John W. Colquitt, colonel, First Arkansas Rich. J. Person, major, Third and Fifth Confederate G. S. Deakins, major, Thirty-fifth and Eighth Tennessee J. H. Collett, captain, commanding Seventh Texas J. H. Kelly, brigadier-general, commanding Cavalry Division Patrick Cleburne was a very shy and unassuming figure with a quiet determined inner drive. Yet he carried an undeniable emanation of authority and competence about him. He was extremely introverted, often avoiding social situations. He was extremely shy around women. That would change abruptly on January 13, 1864. Cleburne acted as best man at the wedding of close friend and superior commander William Hardee to Mary Lewis Forman near Demopolis, Alabama. There he first laid eyes on twenty-four year old Susan Tarleton, maid of honor to her best friend, “Mollie” Lewis. The wedding guests left the next morning by steamboat for Mobile, where Cleburne spent the remainder of his furlough, his first since the war began. Their he proposed to Susan only days after meeting her. She hesitated in her decision but did not discourage him. In February, he received another furlough and returned to Mobile. He later wrote to a friend, “After keeping me in cruel suspense for six weeks she has at length consented to be mine and we are engaged. I need not say how miserable this has made me.” A fall wedding seems to have been planned. Unfortunately, the war woulde come between Cleburne and Susan Tarleton after he departed Mobile in early March 1864. They would never see each other again. Like countless other soldiers and their loved ones back home, the couple tried to stay in touch by mail. The shy, formal, no-nonsense general would reveal another side of his character in his letters to Miss Tarleton. The letters, said aide Leonard Mangum, “were often revelations, even to one who knew him well, as to the depth of his feelings. Devoid of all approach to sentimentality, they were full of a most sweet and tender passion." Before the tragic and fatal charge at the bloody Battle of Franklin Tennessee that Cleburne seemed to know would be his last he reluctantly but bravely did his duty. Despite seeing the futility of a successful assault, he accepted his final order, stating to his superior commander Lt. General John Bell Hood, "I will take the enemy's works or fall in the attempt." His closest aide stated, "Well General there will not be many of us that get back to Arkansas." Cleburne's response: "Well Govan, if we are to die, then let us die like men." Govan would survive the blody morass to see Arkansas once again. But by that day’s end, in the words of his former Adjutant Captain Irving A. Buck, ‘the inspiring voice of Cleburne was already hushed in death’ Cleburne rode to a site called Breezy Hill just before deployment of his division and surveyed the Union defenses down on the Harpeth River that flowed through the once sleepy town of Franklin. As he peered through a borrowed snipers telescope he spoke aloud to no one in particular, "They have three lines of works." "And they are all completed." "They are most formidable." Cleburne advanced on horseback in a charge with his men directly into the center of the Union Line. The horse that bore him was shot from under him. Asking to borrow another, Cleburne placed his feet in the stirrups to mount just as that animal was struck by a cannonball and killed. Cleburne drew his sword and charged on foot at the center of the line where he could see the Bonnie Blue Flag being raised on the parapet. He was struck some 50 yards from the trench line by a bullet in the heart and died instantly. Major-General Patrick Ronanyne Cleburne's body was taken to nearby Carnton plantation. He was lain out for morning on the porch along with General John Adams, General Hiram Granbury, and General Otho Strahl, all who perished in the bloody trenches at Franklin. He was initially interred at Rose Hill near Franklin. His body was soon moved to St. John’s Church, Ashwood, Tennessee. Cleburne had passed this cemetery just days earlier during the advance into Tennessee and remarked that it was ‘almost worth dying for, to be buried in such a beautiful spot��. In 1870 his body would be moved once again for the final time, this time returning to his adopted State in Arkansas, where he remains in Maple Hill Cemetery, Helena. Back in Mobile, Susan Tarleton waited anxiously for any kind of word from the man she loved dearly. Union raiding parties had cut all telegraph lines into the city. Six days after the Battle of Franklin, as she walked in her garden she heard a passing newsboy shout: “Big battle near Franklin, Tennessee! General Cleburne killed! Read all about it.” She fainted dead away. After spending a year confined to her bedroom in “deepest mourning,” Susan Tarleton reluctantly re-entered life. In 1867 she married Captain Hugh L. Cole, a former Confederate officer and an old college friend of her brother’s. Less than a year later, she died unexpectedly of an apparent brain effusion. While growing up in Ireland Patrick Cleburne learned valuable lessons of the harsh realitys that life often presented. He also developed an incredible work ethic. While in the British army, he had learned patience, discipline, self-control, and how to live a life of self-denial. He also came to deeply appreciate the position and suffering of those at the mercy of tyrannical authority in the form of a far too powerful central government. Those lessons served him well as the leader of the men he drilled and prepared to go into battle with. Duty is not just following orders. It is seeing that some ideals and some causes are bigger than one's self, and duty in its deepest sense is the following orders that one does not always agree with. One of his closest friends, Lt Gen. William J. Hardee said of Cleburne after his death, "He was an Irishman by birth, a southerner by adoption and residence, a lawyer by profession, a soldier in the British army by accident, and a soldier in the southern armies from patriotism and conviction of duty in his manhood."

0 notes

Photo

A PHENOMENAL STORY FROM THE BATTLE OF FRANKLIN TENNESSEE. November 30th 1864. By the time the American Civil War began, Theodrick “Tod” Carter was 20 years old and a lawyer. When Tod’s older brother, Moscow, raised a company of men from around Franklin, Tennessee to support the Confederacy. Tod joined what would become Company H of the 20th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. For over two years, Tod’s war service was fairly mundane. But that would change on November 25, 1863 when Tod’s 20th Tennessee defended Missionary Ridge outside of Chattanooga. Union General George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland rushed Confederate positions high on the ridge overlooking the city. The Confederates abandoned their positions and fled east. Tod would be captured during the battle and sent to the Johnson Island prison camp outside of Sandusky, Ohio. Prisoner of war camps were places of pure misery, riddled with disease and death. Tod survived Johnson Island and was in the process of being transferred to Point Lookout, another prisoner of war camp, outside of Baltimore, Maryland, when he escaped from the train transporting him by jumping off. He roamed the wilderness of Pennsylvania, alone and hunted, but determined to find his old unit. On foot, he would eventually make his way over 600 miles to Dalton Georgia where he was reunited with the 20th Tennessee. Now a part of John Bell Hood's Army of The Tennessee he would begin marching north from Atlanta towards his home in Franklin. Desperate to see his family again, in his pocket was a furlough allowing him leave to spend precious time with them. The Army of The Tennessee's march took them directly to Franklin. In their small, brick home next to the main road leading into town, the Carter family waited, knowing that Tod’s old unit was near. They may now have known that Tod wasn’t dead as was first feared Tod's brother Moscow had written Tod a letter while at Johnson's Island, in it he stated “I have a little piece of news you many never have heard before. After your capture, your horse swam the river, and returned to camp in full rig. The boys thought for a long time you were killed, seeing your horse without you.” They still could not have known that their courageous son had escaped from a train, and walked cross country to join up with his old unit? That same morning Tod Carter prepared to finish his journey toward home and visit his loved ones. Earlier that day Union General Jacob D. Cox had knocked on the door of The Carter Home informing Fountain Branch Carter that he would be using the Carter house as a command headquarters. He informed the family that their was very little chance of a battle ensuing, due to both armies being exhausted from their long tedious marches. (Little did he know what that day beheld), Tod managed to slip through the Union lines, and made it to the edge of the Carter garden, where he began to enter through the gate. As he lifted the latch, one of his relatives motioned for him “to go back.” Later in the afternoon of November 30, 1864, Hood decided to launch an attack against the entrenched Federal forces in Franklin. The massive frontal assault was launched against the center of the Union line, which stretched across the land owned by Tod’s father. Called the Pickett’s Charge of the West, Franklin would be the scene of the bloodiest and most gruesome five hours The Civil War. Legend has it that as the 20th Tennessee approached the Union lines dug across the Carter family property, Tod shouted to his comrades, “I’m almost home! Come with me boys!” Just some 200 yards from the home in which he grew up, Tod Carter was struck by 9 bullets and lay in the family’s garden severely wounded. After the battle, as Union troops moved north to Nashville, Confederate soldiers sought out Fountain Branch Carter to inform him that his son Tod had been engaged in the battle and had fallen on the family’s property. Tod had been an aide to Brigadier General Thomas Benton Smith CSA (pictured below). Although Carter’s duties as assistant quartermaster and aide to Smith exempted him from engaging in battle, he vowed that, “No power on earth could keep him out of the fight.” Smith would grimly step through the smoke filled darkness over voluminous piles of dead and wounded men in The Carter yard just moments after The Bloody Battle of Franklin Tennessee had terminated. He arrived at The Carter home to inform the family that their son Tod lie gravely wounded just a few hundred yards away. The Carter family along with their servants, their neighbors and the Albert Lotz family emerged from the root cellar, all unharmed and thanking God for their well-being. What they saw would out do the most graphic horror movie. Major General Benjamin Cheatham C.S.A. who served in numerous major engagements during the war including Shiloh, (24000 casualties), Chickamaugua, (35000 casualties) and Stones River, (24000 casualties) wrote. "Just at daybreak, I rode upon the field and such a sight I never saw and can never expect to see again. The dead were piled up like stacks of wheat or scattered like sheaves of grain. You could have walked all over the field upon dead bodies without stepping upon the ground....Almost under your eye, naearly all the dead, wounded, and dying lay. In front of the Carter house, the bodies lay in heaps, and to the right of it, a locust thicket had been mowed off by bullets, as if by a scythe. It was a wonder that any man escaped alive....I never saw anything like that field, and never want to again." Tod’s family climbed over the body covered breastworks and blood filled trenches carrying gasoline lanterns. It was just before daybreak when they found Tod, laying on the cold ground, incoherently calling out a friend Sgt. Cooper’s name. Nearby lay Carter's grey horse Rosencranz, beautiful even in death. Tod was brought home barely clinging to life after being shot nine times, once in the head. The regimental surgeon removed the bullet, (pictured below), from his skull, but gave little hope for his recovery. Frances A. McEwen a young schoolgirl who resided in Franklin later wrote: "As we approached the Carter House we could scarcely walk without stepping on the dead or dying men. We could hear the cries of the wounded, of which the Carter house was full to overflowing. As I entered the front door, I heard a poor fellow giving his comrades a dying message for his loved ones at home. We went through the hall and were shown into a little room where a soft light revealed all that was mortal of the gifted young genius, Theo Carter, who under the pseudonym of "Mint Julep", wrote such delightful letters to The Chattanooga Rebel. Bending over him, begging for just one word of recognition, was his faithful and heartbroken sister." Tod would pass away the next day without really ever regaining conciousness. His father did say that shortly before Tod expired that he seemed to recognize that he was finally home. Just two weeks later Gen. Thomas Benton Smith would be forced to surrender at the Battle of Nashville. After surrendering his weapons to Union Colonel William McMillen whose brigade suffered heavy losses in the fight with Smith's brigade, Smith and his men were marched, along with 1,533 others, through the Federal dead and wounded, who lay thick on the steep slopes of the Overton Hill. The Union soldiers realized the Confederates had surrendered and, according to one Illinois soldier, began “shouting, yelling, and acting like maniacs for a while.” Apparently, this angered Smith. As he was being marched to the rear, eyewitnesses reported that he allegedly exchanged words with McMillen. Two fellow prisoners, Monroe Mitchell, a private of Company B and Lieutenant J.W. Morgan of Company F, 20th Tennessee Regiment, recalled that McMillen appeared drunk. Whether he was intoxicated or inflamed from the recent bloodshed, his temper overcame him, and he began verbally abusing Smith. Mitchell and Morgan said Smith’s only reply was, “I am a disarmed prisoner.” At that remark, McMillen struck the twenty-six-year-old Smith over the head with his saber three times, each blow cutting through Smith’s hat, the last driving him to the ground, and fracturing his skull, inflicting serious brain damage. Observers believed McMillen would have continued the brutal assault had his own men not pulled him off. Smith was initially given a dim chance of survival. He was told by a Union Surgeon, “Well you are near the end of your battles, for I can see the brain oozing through the gap in the skull.” Smith would never fully recover from McMillen’s cowardly attack. For the remainder of his life, he would suffer from bouts of depression and mania which resulted in his spending much of his remaining 47 years of life in the Tennessee Central Hospital for the Insane

0 notes

Photo

AN ANGEL OF MERCY BECOMES THE WIDOW OF THE SOUTH I just returned in December from visiting the historic Carnton Plantation in Franklin Tennessee. While only one spot on the bloody battlefield of Franklin Tennessee on November 30th 1864, the story of that one bloody night is so incredibly horrific, that it defies the imagination. After the five hours of intense carnage and desperate hand to hand combat their would be roughly 10000 souls who were either killed, wounded or captured. Sarah North Martin was a resident of nearby Columbia, Tennessee just south of Franklin in November 1864 as both the Union and Confederate armies swept through the town during Southern General John Bell Hood’s “invasion” of Tennessee. Sarah, the wife of prominent local judge, William P. Martin, was taken by surprise on November 24, 1864 when two brigades of Union infantry under Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox Jr. commandeered ground on the Mount Pleasant Road. Before they were in position Union cavalrymen came hastily down the gravel road, fleeing from the brigades of Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry. Cox had three artillery batteries along with his troops on both sides of the road. More Confederate troops later arrived and sought to displace the Yankees. Sarah Martin’s thoughts as she and her family escaped, are part of a remarkable letter she sent to a relative:

The fighting commenced at our house, which is situated about 50 yards from the road on a high hill. I dare not write the particulars. Suffice it to say the Yankees had possession of our home & forced us to leave. We went to Mr. Martin’s fathers’ [i.e. George M. Martin], about 800 yards nearer town, taking with us the bedding of three beds & most of our wearing apparel. We were between the fires of the two contending parties for two days, & five shells struck [his] father’s house while [we] were in it, until we had to go down to a brick milk cellar in the yard, the minie balls falling on the roof like hail. The wounded Yankees [kept] passing through the yard, bleeding & screaming with pain. We could hear the yells of the Rebels as they charged & drove the Yankees toward town. At last, when the fight was evidently beyond us, I ran out quickly to avoid the sharpshooters, & entering the [George M. Martin] house, found Gen. [Colonel Edmund Winchester] Rucker’s staff, who showed us every courtesy. Each officer took charge of one of us, & led us in the line of the house, over to [our] home; procured an ambulance and sent us down to Gen. Pillow’s. [this was “Clifton,” four miles west of Columbia, the home of Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow, who was married to her husband’s sister (Mary Martin Pillow)] Gen. [Brigadier General Stephen Dill] Lee had possession of our house, & artillery was planted in several places on the hill. The Yankees [had] sacked our house, & set fire to it, but Forrest came in time to extinguish the flames, before any serious damage was done. They [Yankees] threw our wheat into the pond, burned piles of bed clothes & books, & threw our china all over the yard, took the most of twenty-two hogs, and killed nineteen shoats, took all our horses, etc. In short I cannot enumerate our loss, or tell you how the Yankees treated us. We have ever since been living on biscuit[s] & milk, without a parcel of meat, for we have no money to buy with. You can have no conception of the oppression, & we dare not murmur. Even yesterday they came & took the only animal we had, a mule. Judge M. [i.e. her husband Judge William P. Martin] walked to town to day in the rain to try to get it back, but was unsuccessful, & now we have nothing to plow with, or to haul wood, for we had been driven to hauling wood in a cart. We are very anxious to sell & move to Texas… All our negroes ran off during the fight, & went with the Yankees in their retreat to Nashville. Some of them want to come back, but we will not receive them. The Lord has mercifully preserved our health, & I hope will bring us safely through these troubled times. Just six days later both armies raced towards Nashville for a final bloody showdown. The Union Army was delayed in Franklin due to the swollen Harpeth River. They were ordered to hold their position and dig defensive fortifications as a purely protective measure until they received pontoons from Nashville to move men and equipment across. They did not believe that a major battle would ensue their. But Confederate Lt. General John Bell Hood had other ideas. Seeing the Union Army split and penned against the swollen stream, he decided to launch an all out offensive. General Jacob Dolson on this day would awake Fountain Branch Carter at 4:30 AM to inform him that his home was being commandeered. As the likely spectre of a major battle grew more likely, the town residents hunkered down to bear a fear and horror no human being should ever have to experience. The following are a list of eyewitness accounts of that cold terrible November evening in 1864: "The Men seemed to realize that our charge on the works would attend with heavy slaughter, and several of them came to me bringing watches, jewelry, letters and photographs, asking me to take charge of them and send them to their families if they were killed. I had to decline as I was going with them and would be exposed to the same danger. I was vividly recalled to me the next morning, for I believe every one who made this request of me was killed." Chaplain James H. M'Neilly Quarles Brigade "When Conrads brigade took up its advanced postion we all supposed it would be only temporary, but soon an orderly came along the line with instructions for the company commanders, and he told me that the orders were to hold the postion to the last man, and to have my sergeants fix bayonets and to instruct my company that any man, not wounded, who should attempt to leave the line without orders, would be shot or bayonetted by the sergeants." Capt John K. Shellenberger 64th Ohio Inf. "When I regained consciousness I was laying in the ditch . . of running water and could feel the loose dirt fall in on me when Yankee bullets would strike the top of the ditch . . I became thirsty but had fallen on my canteen but could not get to it... I drank the water in the ditch and it was cold and good. I knew my sight was destroyed. I placed my hands under my forehead to keep my face from above water .. and fell asleep" Lt. Mintz 5th Arkansas, Govans Brigade I saw a Confederate soldier, close to me thrust one of our men through with a bayonet and before he could draw his weapon from the ghastly wound his brains were scattered on all of us that stood near, by the butt of a musket swung with terrific force by some big fellow whom I could not recognize in the grim dirt and smoke.. As I glanced hurredly around and heard the dull thuds, I turned from the sickening sight and glad to hide the vision in work with a hatchet for I had broken my sword. Col Wolf 64th Ohio Conrad's Brigade "The slaughtering could be seen down the line as far as the Columbia and Franklin Pike, and where the works crossed the pike . . . Our troops were killed by whole platoons, Our front line of battle seemed to have been cut down by the first discharge for in many places they were lying on their faces in almost as good order as if they had lain down on purpose; but no such order prevailed among the dead who fell in making the attempt to surmount the Cheval-de-frise, for hanging on the long spikes of this obstruction could be seen the mangled and torn remains of many of our soldiers who had been pierced by hundreds of minie balls and grape shot ... The ditch was full of dead men and we had to stand and sit upon them. The bottom of it from side to side was covered with blood to the depth of shoe soles" James M. Copley 49th Tennessee Quarles' Brigade " as evening came on the neighboors began to come in . . and we went down in the cellar. Grandpa had already put rolls of rope in the windows. . to keep the bullets out. The negroes crouched down in the dining room, and all the children & grand children and neighbors in the hall cellar, and granpa walked back and forth and watched out the window." "The first sound of the firing and the booming of cannons, we children all sat around our mothers and cried." Alice M. Nichol age 8 Tod Carters neice "The mangled bodies of the dead rebels weere piled up as high as the mouth of the embrasure and the gunners said that repeatedly when the lanyard was pulled the embrasure was filled with men crowding forward to get in who were literally blown from the mouth of the cannon. Only one rebel got past the muzzle of the gun and one of the gunners snatched up a pick and killed him with that. the ditch was piled promiscuously with the dead and badly wounded and heads arms and legs were sticking out in almost every conceivable manner. The ground near the ditch was filled with the moans of the wounded and the pleadings of some of those who saw me for water and for help were heartrending." Capt John K. Shellenberger 64th Ohio Inf. Conrad's Brigade "Nothing could be heard but the wails of the wounded and the dying, some calling for their friends, some praying to be relieved of their awful suffering and thousands in the deep agonizing throes of death filled the air with mouthful sounds and dying groans" Capt. Hickey 1st Missouri Cockrells Brigade "I could hear the wounded calling for help in every direction. I again wanted water and thought I would again drink from the water in the ditch, biut this time it tasted of blood and I managed to get my canteen from under me and drank from it." Lt. Mintz 5th Arkansas, Govans Brigade (who has been blinded) "I stood on the parapet just before midnight and saw all that could be seen. I saw and heard all that the eyes, or my rent soul contemplate in such an awful environment. It was a spectacle to chill the stoutest heart...the wounded shivering in the chilled November air; the heartrending cries of the desperately wounded and the prayers of the dying filled me with an anguish that language cannot describe. From that hour I have hated war. Colonel Isaac Sherwoood 111th Ohio Infantry "I remember seeing one poor fellow, sitting up and leaning back against something whose lower jaw had been cut off by a grape shot, and his tongue and under lip were hanging down on his breast. I knelt down and asked if I could do anything for him. He had a little piece of paper and an envelope. He wrote: No, John Bell Hood will be in New York before three weeks." Teenager Hardin Figuers, Franklin resident moments after he emerged from shelter. "God forgive me for ever wanting to see or hear a battle! You had to look twice as you picked your way among the bodies to see which were dead and which were alive and often a dead man would be lying partly on a live one, or the reverse. And the groans, the sickening smell of blood! I noticed while wandering along the earthworks that all or nearly all of the Union soldiers were shot in the forehead. In front, the ground was covered with bodies and pools of blood. the cotton in the old cotton gin was shot out all over the ground. Our Union soldiers had been stripped of everything but their shirts and drawers, but the Confederate soldiers could not be blamed much for that, for they were half clothed, half barefoot and many of them bareheaded." Carrie Snyder; a Union sympathizer who happen to be visitig friends in Franklin at the time. "In this yard and in that garden, I could walk from fence to fence on bodies, mostly those of Confederates. In trying to clean up, I scraped together a half a bushel of brains right around the house, and the whole place was dyed in blood. Nothing in the shape of horse, mule, jack, nor jinny was left in this neighborhood. In fact I remember it was not untilChristmas, twenty five days afterwards, that I was enabled to borrow a yoke of oxen, and I spent the whole of that Christmas Day hauling seventeen dead horses from this yard." Moscow Carter: Brother of Captain Tod Carter recalling what he saw upon emerging from The Carter House root cellar. "Amid the hundreds of dead and wounded Confederates who lay thickly scattered over the field in our front....there was one lying in front of my company, only a few distant feet crying "Mother you were right, you'll never see your boy again. I'm dying out here in the dark....I'm bleeding to death. "The boy's voice became gradually weaker and weaker until we heard it no more......One of the company's new recruits, a mere boy in years, was crying as though his heart was broken. He too was the only son of a widowed mother.": An unknown officer of the 63rd Indiana. The carnage was so great throughout the town that any available structure was used as a hospital. To put this into proper perspective, for every single resident who resided in Franklin Tennessee (pop. approx. 900) there were 7 casualties. The Carnton house quickly became a field hospital for Confederate wounded. It was a ghastly scene of pain , torment, and suffering. The McGavocks tended for as many as 300 soldiers inside Carnton alone, though at least 150 died the first night. John and Carrie McGavock and their 9 yr old daughter Hattie and 5 yr old son Winder helped tend the over 300 men who lay throughout the home. Soon the outbuildings were filled with hundreds more until the only place to lay them were in the yard. After the battle, on December 1, Union forces under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield evacuated toward Nashville, leaving their dead, including several hundred Union soldiers, and their wounded who were unable to walk. The residents of Franklin were then faced with the task of burying over 2,500 soldiers, most being Confederates.The following are some of the first hand accounts of the nightmarish eve at Carnton: "Every room was filled, every bed had two poor, bleeding fellows, every spare space, niche, and corner under the stairs, in the hall, everywhere -0 but one room for her own family. Our Doctors were deficient in bandages, and she began by giving her old linen, then her towels, amd napkins, then her sheets and table clothes, then her husband's shirts and her own undergarment. During all this time the surgeons plied their deadful work amid the sighs and moans and death rattle. Yet amid it all, this nobel woman. . . was very active and constantly at work. During all the night neither she nor any of the household slept, but dispensed tea and coffee and such stimulants as she had and that two with her own hands.. she walked from room to room from man to man her very skirt stained with blood." Capt. William D. Gale - Lt. Gen Alexander P. Stewart's staff "Give me forty grains of morphine' he called out all through the night. 'Give me forty grains of morphine and let me die!' 'Oh Can't' I Die?' ' My Poor Wife and Child!'' My Poor Wife and Child!' "OMG ! Can you get the surgeons to administer some drug that will relieve me of this torture" I did try through my appeals were in vain. " Cold presperation gathered in knots on his brow and of course (he) knew that death was inevitable. . . "I went down the steps and far beneath the silence of the stars to escape his piteous prayers." C. E. Merrill Adjutant General , Brig. Gem Scott's Staff All of the Confederate dead were buried as nearly as possible by states, close to where they fell, and wooden headboards were placed at each grave with the name, company and regiment painted or written on them." Many of the Union soldiers would later be re-interred in 1865 at the Stones River National Cemetery in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Over the next eighteen months many of the markers either rotted or were used for firewood, and the writing was disappearing. To preserve the graves, John and Carrie McGavock donated 2 acres of their property to be designated as an area for the Confederate dead to be re-interred. The citizens of Franklin raised the funding and the soldiers were exhumed and reburied in the McGavock Confederate Cemetery for the sum of $5.00 per soldier. A team led by George Cuppett took responsibility for the reburial of 1,481 soldiers. The names and identities of the soldiers were recorded in a cemetery record book by Cuppett, which soon fell into the care of Carrie McGavock. It is said that for years following the war visitors would knock on her door requesting the book to see if they could find closure from the loss of a loved whom they never knew of their fate. Carrie never failed to fulfill those requests. Carrie McGavock spent nearly 40 years of her life maintaining the McGavock Confederate Cemetery. In her later years she also would help to raise orphaned children, many of which were created by that bloody war. It was the most sincere expression of the heart and compassion she personified for so many years. Carrie died in 1905 and rests beside her husband, John, within sight of the nearly 1,500 Confederate soldiers who they protected and watched over for so many years. The mere thought of young children having to witness so much blood and suffering should draw deep emotions from even the coldest of souls. This was truly an experience where nightmares were born. Harriet (Hattie), Young McGavock was only nine-years-old on the day of the Battle of Franklin. That afternoon and night, she and her younger brother, five year old Winder, and their parents, John and Carrie, watched as their home became a hospital and mortuary. Hattie and Winder worked alongside their parents throughout the night, helping where they could as the battered bodies poured in to the house. The next morning, the bodies of four Confederate generals, who had been killed in the fighting, were brought to the McGavock home and laid side-by-side on the back porch. They were Patrick Cleburne, John Adams, Hiram Granbury, and Otho Strahl.

In Hattie McGavock Cowan's own words over 50 years later:

I can still sense the odor of smoke and blood. I recall how the startled cattle came home from the pastures, how restless they became, sniffing and excitedly running about the place, bewildered by the smell of the battlefield. I can still see swarms of soldiers coming with their dead comrades and lying them down by the hundreds under our spacious shade trees and all about the grounds. I shall carry those awful pictures in my mind down to the day of my death. I was only nine-years-old then, but it is all as vivid and as real as if it happened only yesterday. I overheard a man at Carnton that night say he estimated over 300 wounded were crammed in to our home. There we were in this ocean of suffering — mother, father, Winder and me — going from man-to-man doing what we could. Mother ordered the bed sheets and linens torn into bandages. Those ran out so, she told the medical attendants to use her tablecloths, towels, and father’s shirts. At one point, she used her own undergarments, put to use mending the myriad of wounds. Those who saw her were awestruck by her selfless actions. Mother never ceased in her work that long and dreadful night. She handed out tea and coffee and went from room to room making sure there was nothing else she could do. William D. Gale, of Gen. A.P. Stewart’s staff, said mother was so involved in affairs that her skirt was “stained in blood.” I remember it vividly. Some of the soldiers recuperated at our home until June, nearly seven months after the battle. There was a lot of bad, but there was a lot of good. You sometimes see the best in people under these circumstances. We just went to work and did what we could. I stuck by my mother. Chaplains, doctors, and agents of the U.S. Christian commission showed up over the coming weeks and months.

What happened to Hattie McGavock Cowan?

She married a Confederate veteran named George Cowan at Carnton on January 3, 1884. They lived in close proximity to Carnton for many years in a home known as Windermere. George died in 1919. Hattie lived until 1931 and for many old Franklin residents she was the last living connection to the Battle of Franklin. She is buried with George at Mt. Hope Cemetery in Franklin. Winder Mcgavock took over Carnton after his mother's death in 1905. He died just two years later. While touring Carnton (which would cost over 10 million in modern day currency) visitors can still see the blood stains in the wooden floors from over 150 years ago. The operating table used by surgeons was set up "rather ironically" in the nursery. It consisted of two saw horses and a barn door. It is still on display their today. Hattie Mcgowan quite vividly retold of her memories of that bloody night in an interview she gave shortly before her death in 1931 recalling the smell of blood and powder smoke and the sounds of the intense suffering of the wounded. One can only imagine the nightmares these two children experienced for years afterwards.

0 notes

Photo