ellapainting

44 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

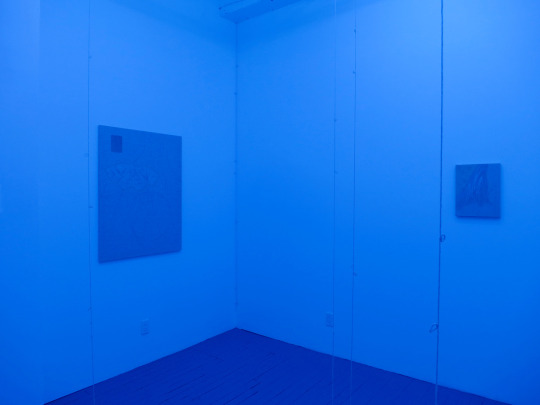

From John, as part of HOUSE BOAT GOOD WATER at goodwater gallery

0 notes

Text

Rhea Dillon, She was washing dishes. Her small back hunched over the sink—a winged but grounded bird, intent on the blue void it could not reach., 2023 Brass and polyester 8 1/4 x 3 1/2 x 4 7/8 in

0 notes

Text

"Thinking of painting as a fold invites a reimagining of its volume, not as physical depth, but as a conceptual space. Like SketchUp, which simulates the third dimension through the second, or like the diaspora, which is shaped by memory, displacement, and fragmentation, the fold gestures toward volume while refusing total access. I'm drawn to painting's ability to hold layered and sometimes contradictory meanings. A volume not inhabited, but imagined; one that exists on and through the surface. It is both object and message, container and content. The fold creates space not just for potential, but for multiple coexisting viewpoints. Through this lens, my work aligns with Édouard Glissant's concept of opacity, which affirms the right to remain partially unknowable and resists the demand for complete legibility. Through opacity, the fold and abstraction offer a model for thinking about diasporic experience as irreducible to a single narrative. It invites viewers to hold complexity without resolution, to see from another angle, and to accept that some aspects are not enterable. This is not a lack of understanding, but a different kind of knowing; one that values difference, preservation and the possibility of alternative perspectives."

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Hanna Hur, The Lovers (2016) at Roberta Palen, Toronto

"Can a painting heal me, she asked? Can a drawing speak?"

0 notes

Text

My favourite Margaux Williamson painting from Shoes, books, hands, buildings, and cars (2025) at the MOCA, Toronto

0 notes

Text

Fergus Feehily

Fergus Feehily makes paintings, but sometimes only just. Dovetail (all works 2011) can’t boast an iota of actual paint: it’s a polyhedral sheet of scarred found wood with three bevelled corners, the lower left one revealing a rumpled and fraying fold of synthetic green cloth. The unassertive scale of the whole – dainty enough to be wall-mounted on slim golden panel pins – ensures you move in close, so that its scratches, knots and radiating waterstains shimmy forth as an ad hoc, quasi-ironic abstract composition. Tally the push-pulls: deliberation vs. accident; hard vs. soft; fixity vs. impermanence (removed from the wall, it would most probably fall apart); the title’s carpentry/nature dualism. There are many paths to the painterly, and the Dublin-born artist is clearly actively interested in such formalistic fence straddling: Feehily’s own website, fearless of cliché, attests to ‘a long-term preoccupation with blurring boundaries’ as well as a desire to engender ambiguity and anxiety.

Yet the eight compact works in his first London solo show operate most winningly – and pleasurably – in micro mode: in accumulations of near-subliminal pictorial events that reward an unhurried, particle-magnifying gaze. The works are hung diffidently low on the wall. You peer down into them, parsing their secrets. Deep engagement with Dovetail reveals an almost imperceptible furze of fluffy material peeking out from the back, an Easter egg for viewers who’ve learned to look around the sides of Feehily’s paintings, where a lot of the action – if that’s the word – takes place. Birdsong, meanwhile, resembles quite a lot of current painting in that it sweeps its ostensive compositional elements towards the periphery: hugging the contours of Feehily’s cheap cream-coloured found frame are blots of alizarin, chartreuse and golden yellow, leaving a washy steel-grey void at the centre. What’s inexplicably gratifying to discover is a wealth of crazy-paved geometric detail in this void, due to the fact that the paper has evidently been folded and flattened out again; that, and the slow-burning warmth of its yellow underpainting.

There’s an appealing sense of these works as waiting, each inlaid with their handful of concealed quirks. (Even the spacey hang reflects Feehily’s taste for discreet skewing, the pacing varied inexplicably on one wall.) What strikes you is the operation of a consistent if slightly unpredictable sensibility: these are paintings that feel to have been rigorously tuned, arrested when they’re no longer austere and not yet busy. Even the serenely pop-minimal and seriously covetable Chamber – which layers a sheet of light pink-painted wood onto a larger expanse of lightly rumpled, brighter pink synthetic material, then letterboxes them between white-painted wooden battens – has a touch of orange paint around its edges that makes it glow like an Ambilight.

Remember that Feehily seeks anxiety. I’m not sure it’s there, or if you could actually feel disquieted by, say, wondering about those holes clogged with colourful paint in the creased, whitewashed paper of The Night, or about how well secured the purple and green foil is within the blunt backless wooden frame of Picture. Yet the latter painting does feel like a fragment of a larger world, and that’s another side of Feehily’s art: it flirts teasingly with anecdotalism and allegory. Picture feels like an ensnared memory of a party (wrapping paper, a gaudy dress), while the mind snarls up when trying to square the title The Interior World with a swatch of soberly patterned material screwed onto a lavender-painted base: thought’s borderless spaces meeting uneasily with notions of décor, the work being at once exactly what it is and a vehicle for metaphoric flights.

There you are again, push-pull: this isn’t a storytelling art so much as one that lets a viewer waver between (among other things) poles of intangibility and materialism. Behind this sturdy architecting, though, reside two things that can’t be blueprinted or learned. Feehily has a very good eye, and knows how to make modesty feel major. And that, evidently, is plenty.

Martin Herbert

0 notes

Text

Will Benedict

Iconic buildings are signifiers for places: the Leaning Tower is Pisa in the same way that the Eiffel Tower is Paris and the Taj Mahal is India. Like flags, landmarks stand alone, always depicted detached from their context; they’re perfect for stamps, those remote ancestors of thumbnail images on which the marvels of tourism have been reproduced for centuries and circulated among friends and relatives. ‘Bonjour Tourist’, Will Benedict’s first solo show at Giò Marconi, paid whimsical homage to the faded glories of philately, the Grand Tour and social networking. His paintings – including Pisa, The Taj Mahal, The Rock of Gibraltar and Paris(all works 2012) – echo the subjects and rectangular format of postcards, stamps included. Sometimes, Benedict’s paintings even portray actual postcards, with scribbled notes and addresses, and ironic titles such as: Lucie, see you when I see you, Lucie, dream of stone and Josefin, read that bitch.

Thankfully, the artist’s interest in semiotics is subtler: while exploring ready-to-consume, ‘picture-perfect’ images such as stock photos, Benedict confuses the usual distinctions between frame and picture, hand painting and mechanical reproduction. In so doing, he connects with our new ways of seeing – after all, web browsers now allow us to search images not only by keyword (content), but also directly by images (form), effacing hierarchies between origins, versions and authors of a sign. Benedict’s technique is, by itself, a tribute to the mise-en-abîme. First, the artist paints abstract patterns in gouache on ordinary foamcore panels. Then, he removes a rectangular portion of the panel and inlays in it a painted canvas, which often depicts the surreal map of a country (Orange China, Corporate Italian Twilight andMexican Twilight). Sometimes, he also asks friends and models to pose in front of the painted panels: he photographs them alone or in couples, seated behind a table or office desk whose shiny surface reflects the paintings. Benedict then prints the photographs life-size, cuts out the figures and glues them to the original foamcore panel. Seen from afar, the different supports and techniques are hard to distinguish, although Benedict does little to hide his labour-intensive process, which straddles hi-tech collage and DIY Photoshopping. Quite the contrary, in fact: here he displayed the photographic maquettes alongside the paintingsBonjour Tourist (Lucie and Markus) and Bonjour Tourist (Lucie and Markus Yellow Model).

The exhibition unfolded as a sequence of odd, multi-layered conversation pieces, sentimental landscapes and a few flag-like abstract compositions. Benedict invited Lucy Dodd to exhibit her sculpture Piano Pond Pipe (2010) – a piano pierced by a thin copper pipe and a small hookah-like burner. During the opening, a pianist played it while she smoked and struck poses, all of which added to the overall atmosphere of daydreaming and voyages around the room.

Benedict’s smaller, inlaid paintings are the most compelling: they encourage free associations with stamps, posters, tablets, television or newsreader’s sets; landmark after landmark. They all have a much older equivalent: the window overlooking a landscape often found in the background of Renaissance paintings, after which our hypertexts still appear to be modelled.

0 notes