thoughts, notes, related art to the material i come across in my studies/medieval to contemporary/interests in influences of religion, science, art and the occult on the history of british literature

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

English 349: November 4

The Tempest and Forbidden Planet

‘loose adaptation’ the same way Clueless is a loose adaptation of Jane Austen

first big-budget Hollywood sci-fi film

Prospero is Morbius

has secret study

access to occult knowledge

Miranda is Alteira

‘stereotypical pretty dumb blond’

pure, innocent, has never seen a man before

not included in father’s activities

sexual knowledge comes to her over the course of the play

mother removed

Category of servants/slaves

Caliban and Ariel both exhibited to some extent by Robbie the Robot; he is like a conflation of the two

The cook

Like some mix of Trinculo and Stephano

humorous moments where he is looking for liquor

The captain

Ferdinand but reimagined as a more proactive hero

less passive; saves the day

important part of plot, his status is elevated

References/similarities to other readings from our coursework

echoes of the interest in anthropology found in New Atlantis/Man on the Moone

Morbius is a trained philologist; has figured out the hieroglyphics of the alien people

New Atlantis=meeting other people who don’t want them to land on their planet, encounter with the other

similarity to Solomon’s House—tour around all the scientific experiments and technologies, “look how much your tech sucks in comparison to ours”

“Now this is the time to talk about the bonkers parts of the film that are not related to our coursework”

‘2000 centuries’—why such an oddly specific large number instead of just saying infinity?

odd tension present between very large and very small numbers being used

tries to make a big show out of the fancy science but then there are these tiny laser blasters; like the film spent all its budget in certain places and not others

the set where Alteira is outside was the reused munchkin set from The Wizard of Oz

Portrayal of 1950s American values/conception of what it meant to be an American

white male cast with one white female; in line with the 1950s American vision of extreme whiteness, heteronormativity, etc

Only woman on the planet becomes ‘mother nature’

‘acceptable’ power for woman to have would be calling the animals

like Snow White

domestic figure, only woman in house, friends with animals

as she becomes corrupted by initiation into sexual knowledge the animals turn against her

reflection of the myth of Orpheus?

The krell

modelled on figures like King Kong and Godzilla

also called ‘id,’ related to/projection of Morbius’s id

when Morbius wakes up, the krell retreats

represents unmitigated passion that the crew ought to leave the planet

if the Krell is Morbius’s id, and the krell has killed before, is it possible that his unconscious wishes killed his wife?

very Freudian implications

when conscious, he suppresses his desires and the krell lives them out

father-daughter set-up by removing the mother figure; Electra complex

father does not want daughter having contact to other men

Morbius claims that his wife died in labour but if we believe him, we’re just subscribing to his narrative

What is the krell?

scene where scientist made mold of footprint; taloned feet but quadruped who only walks on two feet

appears to be some kind of chimera that echoes Ariel’s harpy form in the banquet sequence

1 note

·

View note

Text

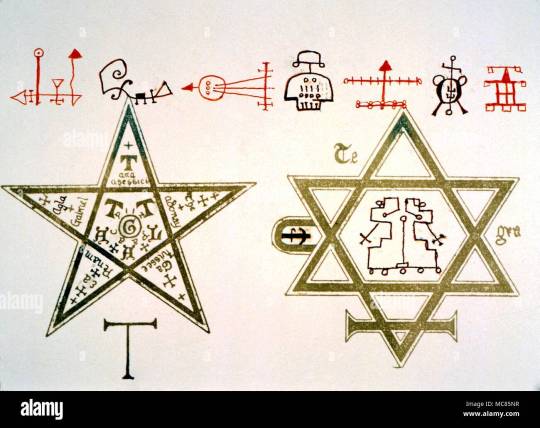

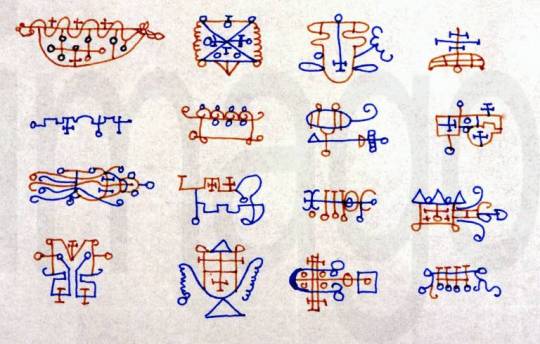

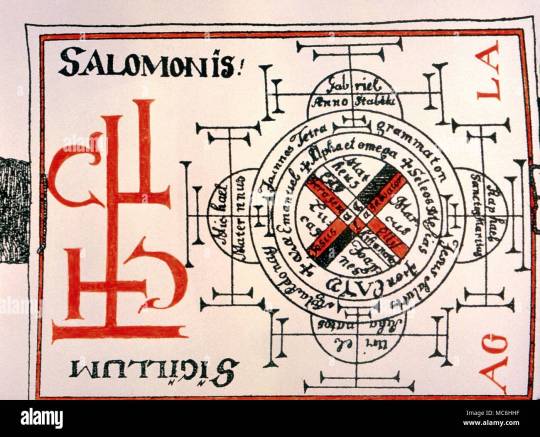

Examples of early Grimoire illustrations (Professor Nardizzi described the Grimoire as the sort of book Prospero would have had in his collections)

0 notes

Text

About Easter tables and telling time in the Middle Ages

0 notes

Text

Hell Isn't Other People--Hell Is Ourselves: The shadow selves of Inez, Garcin and Estelle

For Carl Jung, “the shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort”. The shadow is the part of ourselves we repress, that we wish to not have see the light of day, and this poses a special dilemma as problems tend not to go away unless you fix them. The shadow, once repressed, can only do harm, and in coming to terms with the shadow self and learning to embrace it, it can be brought to the surface and dealt with effectively.

The repressed nature of the shadow self, and the refusal to come to terms with it, serves as one of the main methods of torture for the inmates locked in a room in Hell together for eternity in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit. The acts of not accepting the shadows, the growing pains of recognizing the existence of the shadow selves, and the frustration of being around others who refuse to come to terms with their dark sides are all means by which our characters are tormented en lieu of the traditional torture devices one typically pictures inmates of Hell would face.

The shadow is “the negative side of the personality”, which we can see Inez has a firm grasp of, Garcin struggles with, and Estelle refuses to believe she possesses at all. Of the three, Inez is the most in touch with her own darkness, but a good portion of Inez’s torment comes from trying to help Garcin and Estelle recognize their own dark sides. Garcin has a sense of his own cowardliness, which wanes and waxes over the course of the play, and is subject to a degree of torture by the suspicion that it is there and the refusal to fully acknowledge that it is. Estelle stubbornly refuses to acknowledge her shadow, and in doing so, refuses to help Garcin acknowledge the existence of his own and holds him back from making progress on that front, contributing to avoidable torment for both of them.

The funny thing about the shadow—especially compared to the other parts of the unconscious, which Jung calls the anima and animus—is that the shadow, relatively speaking, is fairly easy to identify. This speaks further to the level of immorality that plagues these characters—the work necessary to uncover their shadow selves is not particularly difficult work, but they lack the moral character to undergo that process. “With a little self-criticism one can see through the shadow—so far as its nature is personal”. Estelle is entirely incapable of engaging in any self-criticism, through her extreme narcissism, and Garcin’s cowardly nature results in his being too afraid to properly engage in such self-criticism. Accepting the shadow, Jung says, goes as follows:

To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge, and it therefore, as a rule, meets with considerable resistance. Indeed, self-knowledge as a psychotherapeutic measure frequently requires much painstaking work extending over a long period.

In this sense, we can see that Inez is actually a perfect embodiment of one who accepts her shadows.

Inez is fully aware of what kind of person she actually is, and she’s fully aware of what she did that was sufficiently evil to land her an eternity in Hell:

When I say I’m cruel, I mean I can’t get on without making people suffer. Like a live coal. A live coal in others’ hearts. When I’m alone I flicker out. For six months I flamed away in her heart, till there was nothing but a cinder. One night she got up and turned on the gas while I was asleep. Then she crept back into bed. So now you know.

She is, quite simply, a cruel person who toyed with the emotions of others, who holds no pretensions about being any kind of saint. This does not make her necessarily any better than the other two—her evil deeds are not lessened by her own recognition of it. But because she has acknowledged her shadow self, her torments in hell will be lesser than those of her unwilling companions.

Estelle nicely embodies another one Jung’s statements about the nature of the shadow:

“It is often tragic to see how blatantly a man bungles his own life and the lives of others yet remains totally incapable of seeing how much the tragedy originates in himself, and how he continually feeds it and keeps it going. Not consciously, of course—for consciously he is engaged in bewailing and cursing a faithless world that recedes further and further into the distance. Rather, it is an unconscious factor which spins the illusions that veil his world. And what is being spun is a cocoon, which in the end will completely envelop him.” (147)

Estelle’s narcissism is so engrained into her that she scarcely recognizes herself as one who embodies some pretty nasty vices, pretending at first to not even know why she was in hell. Inez and Garcin, however, figure her out quickly. The others can see through her more readily than she is wanting them too, discovering almost immediately why she is there based on her fear of a man with a disfigured face. They figured this man attempted suicide on her behalf, and shot himself. She becomes extremely distressed after this revelation is made, and we learn she can barely even admit the fact to herself that she murdered her own baby, prompting the suicide of the man she was cheating on her husband for. Her inability to take responsibility for her own circumstances is a clear byproduct of her repressed shadow self.

Estelle is blatantly obsessed with herself on a surface level, and a surface level only, refusing to believe there is anything to her beyond her appearance; and so one of the ways in which she is tortured is that she is not permitted to have a sense of her physical self anymore, which ideally ought to push her farther towards having to embrace her shadow. Upon arriving in the room where she is to spend eternity, Estelle becomes quickly dismayed by the fact there are no mirrors present. She is expected to reflect on the deeper parts of herself, but becomes desperate to bury her fears in the reassurance of her physical beauty, as demonstrated by the scene in which Inez attempts to comfort her by acting as her ‘mirror.’ Estelle’s fragile sense of self is revealed when she has a vision of herself on Earth, and realizes that not only does she have no mirror in Hell, but she cannot see herself in mirrors on Earth as well:

“I can see them. But they don’t see me. They’re reflecting the carpet, the settee, the window—but how empty it is, a glass in which I’m absent! When I talked to people I always made sure there was one near by in which I could see myself. I watched myself talking. And somehow it kept me alert, seeing myself as the others saw me…”

On some level, the loss of her preferred sense of self is likely causing Estelle to begin coming to terms with her shadow. Estelle is so horrified by this process, however, that she doubles down on her efforts to seclude her true self from the others. In the scene in which Inez acts as her mirror, Estelle becomes distressed by having somebody scrutinize her so carefully, as Inez is likely seeing Estelle in such a way she has never seen herself before. Desperate to reaffirm her sense of her own beauty in the last way she can, Estelle turns to attempting to seduce Garcin, the only man around, so that she can escape having to face the parts of herself that do not relate to her appearance. In doing this, she wishes to regain control over the way in which others see her, by forcing Garcin to find her attractive, as she lost control over how she is perceived when Inez glanced into her face so deeply.

The fact of our characters’ eyes being open all the time is surely significant as well. With the act of being closed off to yourself serving as a torture method, there is some profound irony to be found in the fact that they are being forced into this state of complete transparency towards one another. They quite literally cannot hide any part of themselves from each other, which perhaps would expedite the process of not being able to hide parts of themselves from themselves any longer. Garcin appears to be the most distressed by this revelation: “With one’s eyes open. Forever. Always broad daylight in my eyes—and in my head.” His distress is probably linked to the fact that, unlike Estelle, he has a sense that a darker side of him exists, but unlike Inez, he is not fully ready to open up to it yet. His inability to close his eyes, and the sense of transparency this brings about, is especially significant to him because he realizes that all his secrets are about to be let out into the open.

Garcin’s predicament is perhaps the most interesting of the three because of how he flips and flops between the two poles of attempting to uncover his shadow self and be like Inez, and attempting to bury his shadow self even further like Estelle. He is dimly aware of his own cowardliness—the cowardliness that got him killed and, along with cheating on his wife, contributed to his damnation in Hell—and alternately tries to come to terms with it and convince himself that he is not one.While trying to be more like Inez, he declares:

“A thousand of them are proclaiming I’m a coward; but what do numbers matter? If there’s someone, just one person, to say quite positively I did not run away, that I’m not the sort who runs away, that I’m brave and decent and the rest of it—well, that one person’s faith would save me. Will you have that faith in me? Then I shall love you and cherish you for ever.”

Garcin at this point is the closest he will come to recognizing that he needs to bring his shadow self to the surface, so it can be properly dealt with, and requests that Inez help him recognize this part of himself so he can begin the process of reconciling it: “The curtain’s down, nothing of me is left on earth—not even the name of coward. So, Inez, we’re alone. Only you two remain to give a thought to me. She—she doesn’t count. It’s you who matter; you who hate me. If you’ll have faith in me I’m saved”. Inez, the only one who sees through everybody, has to help him see through himself. The revelation of cowardliness is a particularly difficult one for Garcin, who “aimed at being a real man. A tough, as they say. I staked everything on the same horse… Can one possibly be a coward when one’s deliberately courted danger at every turn? And can one judge a life by a single action?” (44). The discovery Garcin has to make here, is that the answer is yes—he could still be a coward.

The progress Garcin made was enough to excite the reader, but alas, as the play draws to a close, he buries himself in Estelle’s arms, as she seeks confirmation of her own beauty that his attention can provide her with, and she reassures him he is not a coward, undoing the difficult work of discovering the shadow self he had tried to begin. In the end, him and Estelle decide to succumb to their vices together, instead of confronting them, and subsequently, as the shadow selves are more repressed, they will find inevitably find themselves in much deeper misery they could have avoided. Inez mocks the scene, as Estelle and Garcin suppress themselves in affection for one another:

“What a lovely scene: coward Garcin holding baby-killer Estelle in his manly arms! Make your stakes, everyone. Will coward Garcin kiss the lady, or won’t he dare? What’s the betting? I’m watching you, everybody’s watching, I’m a crowd all by myself. Do you hear the crowd? Do you hear them muttering, Garcin? Mumbling and muttering. “Coward! Coward! Coward! Coward!”—that’s what they’re saying…. It’s no use trying to escape, I’ll never let you go. What do you hope to get from her silly lips? Forgetfulness? But I shan’t forget you, not I! “It’s I you must convince.” So come to me. I’m waiting. Come along, now… Look how obedient he is, like a well-trained dog who comes when his mistress calls. You can’t hold him, and you never will.” (46)

While the three are there to torture each other, Inez is rendered a special kind of torturer because both Estelle and Garcin find her ability to see the darkness in everybody absolutely repellant. While they are still playing games and lying about the way they are, and trying to project different versions of themselves onto the scene, Inez asserts that she sees their shadow selves—she sees Garcin’s cowardliness that Estelle is claiming she does not see, and she sees Estelle’s shallowness that Garcin is refusing to see, because he is so desperate to not be seen as cowardly. And so, although Inez recognizes the shadows, she is tortured by being the one who can see them.

Garcin drives home this point about Inez when he says,

“And you know what wickedness is, and shame, and fear. There were days when you peered into yourself, into the secret places of your heart, and what you saw there made you faint with horror. And then, next day, you didn’t know what to make of it, you couldn’t interpret the horror you had glimpsed the day before. Yes, you know what evil costs. And when you say I’m a coward, you know from experience what that means. Is that so?”

Inez knows evil, and fully understands what it means. She does not try to run and hide from it, or pretend to be less involved with it than she actually is. She sees, knows and embraces her shadows. While clearly she is not troubled with the same amount of inner turmoil as the others, she is differently tortured with the realization that she alone carries the burden of being the only one who truly knows why they are all there, and faces the distress of knowing that she cannot really do anything to help Estelle and Garcin come to terms with their true selves.

From this, we can see that No Exit provides us with fascinating grounds for discussion of Jung’s conception of the shadow self, because of the various ways in which both recognizing it, and not recognizing it, can bring us suffering. The shadow self is inherently the part of ourselves that tortures us, and from this, we can also see just how painful and messy the process of trying to reconcile one’s shadow self can be as well. Works Cited

Jung, Carl. “The Shadow.” The Portable Jung. Edited by Joseph Campbell. (Markham, Ontario: Penguin Books, 1971).

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “No Exit.” No Exit and Three Other Plays. Translated by Stuart Gilbert. (New York: Vintage Books, 1955).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A flawed moniker of Freud's: Exactly why Oedipus the King does not have an Oedipus complex

Sigmund Freud’s “Oedipus complex” has had its share of critics over the years, with their charges aimed at it typically consisting of an inappropriate sexualization of children and being pseudo-scientific and unfalsifiable. But perhaps one of the most interesting ways in which it can be found to be flawed is that it is so poorly named. While many fictional stories, such as The Brothers Karamazov, Hamlet, and Psycho, can be accurately said to be representations of the Oedipus complex, the play that shares a name with the complex, upon scrutiny, cannot be found to demonstrate one at all.

The Oedipus complex is rooted in Freud’s belief “being in love with the one parent and hating the other are among the essential constituents of the stock of psychical impulses” that lead to the formation of neuroses; Freud further asserts “this discovery is confirmed by a legend that has come down to us from classical antiquity: a legend whose profound and universal power to move can only be understood if the hypothesis I have put forward in regard to the psychology of children has an equally universal validity”: the Sophocles play Oedipus the King. So clearly, for Freud, Oedipus the King stands in as a manifestation of the child’s latent desire to sleep with the mother and kill the father.

Technically speaking, Oedipus was in love with his mother: she is characterized as his loving partner. And he murdered his father after his father angered him, so it seems we can safely say Oedipus murdered his father out of hatred. However, the chief motivating factor behind the Oedipus complex cannot be found here, as Freud posits the boy wishes to eliminate the father in order to receive greater love from the mother. Oedipus only killed his father out of anger, not because this seemingly random man stood in the way of his receiving his mother’s affections. Any attraction that Oedipus had towards his mother, Jocasta, was also entirely hinged upon the fact of his not knowing who she truly was; for the very moment all is revealed and Oedipus recognizes he has fathered children with his mother, he is moved beyond disgust. He gouges out his own eyeballs, and loses any sense of attraction to her. This cannot, on any level, speak to a secret desire to be with the mother—it speaks to the opposite, that you would lose all attraction to a woman if you discovered she was your mother.

Furthermore, the aforementioned quotation of Freud’s finds itself within a passage concerning the origin of neuroses, which describes “the mental lives of all children who later become psychoneurotics.” Freud’s larger assertion is that early childhood experiences pave the way for what are to become adult neuroses, and the Oedipus complex is one of the events a child might experience that leads to the formation of some of the most severe neuroses. The Oedipus complex, for Freud, is what often produces a child’s earliest sense of shame, as the child faces an impulse which is at odds with what is societally acceptable. The child experiences shame (likely for the first time) stemming from the fact he can never have what he wants, because he would face castration by the father if he attempted to act on this impulse. Oedipus was not raised by his own parents, and did not display these tendencies towards his adopted parents. He committed these acts as a grown man, who was firmly convinced that his parents were Polybus and Merope. So he does not fit the profile of one with an Oedipus complex at all, because the crucial component—its onset in early childhood—is not present.

While in Freud’s eyes, the Oedipus complex springs from an internal source—an innate and inevitable desire—the fate of Oedipus the king was bestowed upon him by external forces that he cannot escape. There is a faint similarity between Oedipus and his namesake complex in that in both cases, there is a sense of inevitability and helplessness. Because the Oracle had declared such would be Oedipus’s fate, and one cannot change their own destiny, Oedipus had no other choice. And in Freud’s eyes, while the boy likely will not act on his impulse, it also cannot be said to be his fault he is experiencing it. But the distinction ends there, as Oedipus had to kill his father and sleep with his mother to fulfill destiny, while the son has no such compelled fate.

In attempt to reconcile the textual details of Oedipus the King with the Oedipus complex, Freud appeals to a quote from Jocasta: “In dreams too, as well as oracles,/many a man has lain with his own mother./But he to whom such things are nothing bears his life most easily.” Freud frames this as a benign comment from Jocasta’s end, which was intentionally inserted by the author to indicate “the legend of Oedipus sprang from some primeval dream-material which had as its content the distressing disturbance of a child’s relation to his parents owing to the first stirrings of sexuality”. A much more obvious interpretation of this comment of Jocasta’s, however, when examined under the context of the play, is she had been merely trying to comfort her panicking son/husband. Additionally, the sentence served a structural purpose of foreshadowing what was to come. The play lacks any textual evidence that in any way, shape or form did Oedipus, secretly or not, desire to sleep with his mother.

From this, we can see that the Oedipus complex, while sharing some similarities to the story of the unfortunate king, cannot actually be used to analyze its namesake. Perhaps Freud would have been better off calling it the equally catchy ‘Karamazov complex’ instead, seeing as that tale featured Dmitri’s intentional violence and aggression towards his father while he was in love with the woman his father was dating at the time…

Works Cited

Freud, Sigmund. “The Interpretation of Dreams.” Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. 2nd Edition. Edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010.

Sophocles. “Oedipus the King.” Sophocles I: Three Tragedies. Edited by David Greene and Richmond Lattimore. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

0 notes

Text

An aging double ends up being confused with the real thing: Dorian Grey's precession of simulacra

For Jean Baudrillard, “to simulate is to feign to have what one hasn’t… simulation threatens the difference between ‘true’ and ‘false,’ between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’”; this sentiment, paired with Lord Henry’s declaration love and art “are both simply forms of imitation” can be viewed as an interpretation of the source of Dorian Gray’s ugly descent into depravity. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, the titular character, upon being made aware of his own charm and beauty for the first time in his life, develops a terror of aging and dying, and begins an attempt to transform into pure simulacra instead of organic man in order to escape death and decay. His precession towards a simulation of pure beauty and perfection begins by his seeking to surround himself with individuals who also live as imitations, severing ties with anybody who he finds to be grounded in reality. When these friendships begin to turn sour, he continues his precession by building a world for himself of beautiful material objects and symbols of greatness passed. But as his sins increase in number, he develops an acute sense of guilt, and his world of symbols is no longer enough to protect him from the reality that he is not just a piece of artwork but a real, living man, whose actions had very real and devastating effects on others.

Three people Dorian is acquainted with mark his story by serving as artists living in various stages of simulacra: Basil, the painter, Sybil, the actress, and Harry, who exists as performance art. Dorian aims to surround himself exclusively with others who are as separate from reality as he wishes to be, and so, these friendships are terminated once Dorian observes a human or detached element from these individuals. The first casualty of Dorian’s precession is his friendship with Basil; Basil whom, of all characters, observes the greatest separation between his life and his art. As he is a painter who captures the essences of real things and people, Basil has the most distinctive boundary between his life and his creations; compared to Sybil, who becomes simulacra temporarily every night, and Harry, who lives as an imitation or parody of life and whose words blur the boundary between truth and provocative half-truth so constantly one ceases to be able to take him seriously at all; rendering him exclusively valuable insofar as he is entertainment. Furthermore, the art produced by Basil is far from simulacra; it captures real things but, to the exception of Dorian’s portrait, does not replace them.

Basil’s art is inspired by things he loves and finds beautiful. He attaches special reverence to the painting of Dorian because it captures what he perceives to be the essence of this beautiful man—it is as close to Dorian as he can get with art. In turn, Basil recognizes himself within his artwork, because when he is successful in realizing his artistic goals, he feels that his true passions are represented in their portrayal. In painting and finding beauty in the existence of another, Basil reveals his own soul to himself: “I know you will laugh at me… I have put too much of myself into it." As the story progresses, Basil begins to work against Dorian’s interests in two ways: by not being a simulation, by saving as an unwanted symbol of Dorian’s past. Dorian needs to eliminate all traces and memories of his organic form in order to become simulacra. Dorian disposes of Basil first by fading him out of his life, progressively spending less time with him when Dorian realizes Basil cannot do more to help him achieve his fantasy; later, he murders Basil to assure his secret concerning the painting can remain his forever, so the creator of the painting cannot be made aware that the painting has become the real man. And such is also why Dorian’s painting transforms from his source of inspiration to something he abhors: after Basil is gone, it is to remain the one thing tethering him to the organic world, the one symbol of his true self it seems he cannot rid himself of, that proves his whole world is not as beautiful as he wishes it to be.

We meet Sybil as Basil’s prominence in Dorian’s life is beginning to fade; Sybil, who is only capable of producing work of artistic merit to alleviate pain and suffering. She may be read as almost a satirical portrait of the notion, held by many, that art is necessarily a byproduct of miserable circumstances. Theatre for Sybil was a means of pulling herself out of her own tragic life and poverty: she was given the opportunity every night to lose herself, transforming temporarily into simulacra, repeatedly performing the roles of women who never existed. Sybil perhaps represents the notion of simulacra the most accurately to Baudrillard’s original conception; as acting is a process of becoming a character who is already a mere simulation of a real person to begin with. She is effectively simulating what is already simulacra. Dorian falls in love with her when he sees her in this simulated state, declaring “.the only thing worth loving is an actress”. He decides she, as such a beautiful symbol, must hold a place in his own increasingly simulated life, and he views her as an abstraction in lieu of a person independent from the roles she plays: “I have had the arms of Rosalind around me, and kissed Juliet on the mouth”. He takes no interest in learning anything about the real her, stating her manager “…wanted to tell [him] her history, but [he] said it did not interest [him]”. Furthermore, Dorian’s desire to maintain a superficial and artistically constructed relationship to Sybil is reinforced by the fact he is reluctant to even share something as real as his name with her, allowing her instead to conceive of him and to refer to him symbolically as ‘Prince Charming.’ Sybil, while discussing her marriage with her mother, even has to confess that “‘he has not yet revealed his real name’”. (Fortunately for Dorian, she thought it was ‘“quite romantic of him’”).

Dorian’s plan deconstructed itself when she fell in love with him and faced the prospect of securing a happy life: marriage, property ownership, children, financial stability. Facing an escape from the life of misery that created this desire to escape, she has no more need to escape through her art. As she represents this notion one can only be a good artist if they are in pain, the cessation of her pains entails the cessation of her talents. Not only has she ceased to be a simulation, she has developed a sense of pride in herself and expresses excitement for her own future, demonstrating she is excited to enjoy her life as something beyond just being a piece of art: “The girl was standing there alone, with a look of triumph on her face. Her eyes were lit with an exquisite fire. There was a radiance about her. Her parted lips were smiling over some secret of their own”. This reclamation of her self confidence and pride is startling in comparison to the meek and frail girl we are introduced to earlier: “‘Oh, she was so shy, and so gentle. There is something of a cild about her. Her eyes opened wide in exquisite wonder when I told her what I thought of her performance, and she seemed quite unconscious of her power’”. When Dorian sees she is more than a simulation, she, too, can no longer serve his needs, and he releases her in disgust. He had loved her because “‘one evening she [was] Rosalind, and the next evening she [was] Imogen. [He had] seen her die in the gloom of an Italian tomb, sucking the poison from her lover’s lips. [He had] watched her wandering through the first of Arden, disguised as a pretty boy'”. He now recognizes Sybil as a complex person, not a mere emulation of others; and she does not belong in his world of carefully curated representations divorced from reality. Perhaps most insultingly to her memory, Harry and Dorian do not even lament Sybil’s passing to the same extent they lament the termination of her acting career: “‘Mourn for Ophelia, if you like. Put ashes on your head because Cordelia was strangled. Cry out against Heaven because the daughter of Brabantio died. But don’t waste your tears over Sybil Vane. She was less real than they are.’” Here, we see the symbols Sybil represented being observed as more real than she was. Dorian even had the gall to request of Basil a portrait of Sybil, so he can preserve a literal simulation of her likeness: “You must do me a drawing of Sybil, Basil. I should like to have something more of her than the memory of a few kisses and some broken pathetic words’”. Sybil, clearly, possessed value to others only as simulation and not as a human.

The only significant friend Dorian has left after Sybil exits his life is Harry, as Harry lives in such a way that twists the nature of reality to serve his own ends exclusively, and has firmly severed most his ties to the world the rest of us inhabit. With Basil, the art and the artist were always distinct and separate; with Sybil, she was only a simulation when she chose to be so. Harry, on the other hand, simulates truth all of the time. He is a relentless provocateur, who spews senseless pseudo-intellectual observations which distort the perceptions of reality of those who take his words to heart—as exemplified in his relationship to Dorian. Prior to meeting Harry, “…one felt [Dorian] had kept himself unspoiled from the world”, and Basil recognizes the horrible potential somebody as manipulative as Harry could have on somebody as manipulatable as Dorian when he pleads to Harry not to “‘…spoil him. Don’t try to influence him. Your influence would be bad’”. But immediately after hearing Harry’s words, “…a look [came] into the lad’s eyes that [Basil] had never seen before,” and Dorian’s downwards spiral is officially triggered. Harry expresses world views which glamorize living as simulation, instead of producing art: “The mere fact of having published a book of second-rate sonnets makes a man quite irresistible. He lives the poetry he cannot write. The others write the poetry that they dare not realize”. Through Harry’s influence, Dorian begins to acknowledge himself solely as a piece of art, and strives to develop the same detachment from reality as Harry. This friendship is now solidified in a way his other relationships could not have been: he can count on Harry to always help him towards his goal of detachment, for Harry is decidedly detached. While the reader watches the conflation of art and life in Dorian's eyes progressing, he begins to attempt to turn not just himself into a work of art; he tries to transform everything else around him into art as well.

Dorian’s obsession with fine interiors and the collection of rare and beautiful goods immediately follows the dissolution of his relationship to Sybil; it can perhaps be interpreted as a result of the tremendous amount of guilt that is starting to build up inside him, as he acknowledges some degree of responsibility for what happened to her, and the portrait begins to transform, displaying this guilt. Now, he wishes to become simulacra not just to evade death, but to protect himself from his own sins. Dorian “collected together from all parts of the world the strangest instruments that could be found, either in the tombs of dead nations or among the few savage tribes that have survived contact with Western civilizations, and loved to touch and try them”; he “would often spend a whole day setting and resetting in their cases the various stones that he had collected”, and begins frequenting the opera, but only in his own company or Lord Henry’s. He has become almost completely closed off from the rest of society at this point, socializing with extremely few people and devoting more time to admiring beauty. He develops an unhealthy fascination with deceased royalty as symbols of pure greatness, most likely because they represent what he wishes to be seen as: “How exquisite life had once been! How gorgeous its pomp and decoration! Even to read the luxury of the dead was wonderful” He prefers objects representing dead people to alive ones; perhaps because he has become an object representing a dead person himself.

As his infatuation with his self as a symbol grows, the line between human and symbol becomes progressively more blurred, until “…something [has] disappeared: the sovereign difference between them that was the abstraction’s charm. For it is the difference which forms the poetry of the map and the charm of the territory, the magic of the concept and the charm of the real”.Towards the end of the novel, Dorian’s life has become all but pure simulacra; to the exception of the unfortunate portrait that serves as the final thing tying him to the reality of his organic nature, after Basil’s murder. His simulation, however, has clearly ceased to be enough to protect him from his own sense of guilt. Basil’s murder also takes both a visible toll on the picture of Dorian, and on his psyche, and his retreats to the opium dens become a necessary release from his guilt: “There were opium-dens, where one could buy oblivion, dens of horror where the memory of old sins could be destroyed by the madness of sins that were new”. For there is no state in which one is closer to experiencing a more perfect simulation of reality than in a drugged dream state, in which the individual is not even physically capable of distinguishing the real from the dream anymore.

Ironically, the sketchy venues Dorian begins to frequent represent a different kind of escape from the life he has built from himself, as “memory, like a horrible malady, was eating his soul away”; they represent an absolute absence of anything artistic and beautiful. “Ugliness was the one reality. The coarse brawl, the loathsome den, the crude violence of disordered life, the very vileness of thief and outcast, were more vivid, in their intense actuality of impression, than all the gracious shapes of Art, the dreamy Shadows of Song. They were what he needed for forgetfulness”. As he used art to escape life, he is now using life to escape art.

The death of James Vane proves to be the last reminder of Dorian’s real implications on the people around him that he can tolerate, and finally, he realizes he no longer needs a escape from reality, but a total escape from the pseudo-reality he has manufactured for himself. In a desperate attempt to save himself from his sins, Dorian stabs the portrait, but unfortunately “… it is dangerous to unmask images, since they dissimulate the fact that there is nothing behind them”. Facing the portrait for the last time, Dorian thought to himself “…he would be good, and the hideous thing that he had hidden away would no longer be a terror to him. He felt as if the load had been lifted from him already”. But alas, the attempt to annihilate the last trace of the original completed Dorian’s precession. The portrait of Dorian Grey is now “…no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even of parody.” The portrait “substitut[ed] signs of the real for the real itself,” and fully and finally became the actual Dorian, in its final form. Baudrillard speaks specifically of the need for the original to perish in order for the symbol to become ultimately real: “Nothing changes when society breaks the mirror of madness… nor when science seems to break the mirror of its objectivity… [E]thnology in its classical institution collapses… in order to conceal the fact that it is this world, our own, which in its way has become… devastated by difference and death”. The novel ends on a final note of irony: the deceased Dorian, organic again and rendered ugly by sin and time, is unrecognizable to anybody who knew him well. His own servants were only able to identify him through one last symbol he left behind for them: he was wearing his rings. “Lying on the floor was a dead man in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they realized who it was”. The beautiful things he admired were more identifiable as Dorian Gray than his actual body. Now, “only the allegory of the Empire remains”. The man has become the simulacra, and the simulacra has become the man.

The moral of the story, once analyzed from this perspective, is hard to decipher. Perhaps it is, as it has been said before, that life is more important than art. Or that, as much as art gives life meaning, art is not a substitute for a meaningful life. One can live in an artful way, but when one ceases to differentiate between real and unreal, it does not appear much good can follow. [2882]

Works Cited

Beaudrillard, Jean. “The Precession of Simulacra.” Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. 2nd Edition. Edited by Vincent B. Leitch, et al. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010).

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2006.

0 notes

Text

The Line Separating Dionysian from Apollonian Runs Through Every Human Heart: Chaos and Order in Goblin Market

There is probably an argument to be made that any piece of literature can be interpreted according to Nietzsche’s theory all art springs from two primal energies: the divinely structured and intentional Apollonian, and the unrestrained, unpredictable Dionysian. Christina Rosetti’s Goblin Market, however, makes for a particularly intriguing instance of a Nietzschean analysis as the two energies can be detected in this story as both a strict physical binary, and as inherent personality traits our characters grapple with from within. The horror element of this story arises once our protagonist crosses the internal and external boundaries between the two, finding herself in the horrible no-man’s-land outside of both.

In the physical sense, the Apollonian is embodied as the world of humankind and the Dionysian as the Goblins’ world. Our human characters are well aware common sense dictates the line is never to be crossed. In the personal sense, the duality of both forces exists in all humans, and it is the Apollonian’s duty to keep the Dionysian impulse in check. When a human physically crosses the boundary between their world and that of the Goblins, it is due to weakness on the part of the Apollonian that cannot sufficiently counter Dionysian curiosity.

Laura’s lapse in Apollonian judgment transpires when she descends upon the Goblin’s fruit “like a vessel at the launch/when it’s last restraint is gone” (85-86). As she consumes the forbidden fruit, she is pushed over the divide between worlds in a spiral towards a Dionysian hell; with the first symptom of her Dionysian illness being her “longing for the night” (214) while her ascetic sister “[warbles] for the mere’s bright daylight” (213). Because she failed to appreciate the separation between human and goblin, between night and day, she is now neither and she is all alone in what she suffers. Subsequently, she finds herself outside of the laws of nature as she is outside the natural state of humanity. As these laws cease to apply to her, she begins to age rapidly and wither away; made to pay for her sin of blurring the boundary by being punished with unstoppable yearning for the same temptation she yielded too. As she would not restrain herself from consuming the goblin’s fruit, the desire for the Goblin’s fruit consumes every waking second of her life as it consumes her physical form. The natural force of time is now unable to control her aging process, and her Apollonian individuated body deteriorates as she withers away, racing towards the Dionysian state of the abolition of the individuated self in the death that follows the disintegration of her physical form.

What saves Laura from her impending demise is her sister, Lizzie, who echoes the presence of another Nietzschean archetype, the Ascetic Priest. Lizzie’s constitution is dominated by Apollonian asceticism, allowing her to resist what her sister could not. In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche wrote the spiritually ‘sick’ needed doctors and nurses who were ‘sick’ themselves; however, these figures in addition to being sick also needed to be strong enough to lead the weak to salvation. In order to help save humanity, Ascetic Priests take the suffering of others upon themselves. The Dionysian exists within Lizzie, as it exists within all of us, and so she is ‘sick’ in part too; but is stronger and more capable of resisting it than her sister. And so, she ventures to the domain of the Goblins, convinced she is strong enough to resist temptation to bring to her sick sister what she so desperately desires.

Because the Apollonian remains strong within Lizzie, she is able to walk down the line between human and goblin without falling to the wrong side of it. While Laura sells the Goblins a part of herself, her hair, in exchange for the fruit because she has no money on her, Lizzie wisely pays the goblins with cash. This maintains the physical separation between herself and them. Wary of her ploy, the goblins ask her to “take a seat with us/Honour and eat with us” (368-369), hoping she will fall prey to their spell as well. When she resists, the Goblins become violent with her, forcing the fruit against her mouth, while “White and golden Lizzie stood” (408), distinctly emulating Apollo himself, stoic and unflinching. When they realize they cannot affect her, she is released, and returns to her sister with the fruit.

The fruit appears to have taken on a different meaning. In the wake of Lizzie’s self-control and her sacrifice for her sister, the fruit loses its Dionysian power and assumes Lizzie’s Apollonian influence. Lizzie tells Laura, “Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices/Squeezed from goblin fruits for you/Goblin pulp and Goblin dew/Eat me, drink me, love me” (467-471). The Ascetic Priest’s suffering for the sake of another caused the fruit to become a cure and not disease. As Laura consumes the fruit, her strength and health return; she assumes the Apollonian once again and becomes well.

Some consider it to be the case that it is unlikely the story would have ended well for Laura at all had it not been for the author’s intent of “Goblin Market” being a children’s tale, and therefore, could not have featured an ending as dark and depressing as one entailing the protagonist’s death. This may very well in fact be true; however, a lot more than just a palatable ending is achieved by allowing Laura to live. The story is transformed from a simple fable into a much more complex piece to unpack and interpret. By resolving the conflict this way, with Lizzie facing torture and torment in what appears to be a helpless attempt to save her sister, motivated purely by love alone and not concern for her own wellbeing, the story ceases to be a simple cautionary tale advising children to resist their temptations. The morality is expanded from exclusively stressing the necessity of restraint to encompassing the power and value of sisterly love and sacrifice for one another as well.

Works Cited

Nietzsche, Frederich. The Birth of Tragedy. Translated by Clifton P. Fadiman, Dover Thrift Editions, 2016.

Nietzsche, Frederich. Genealogy of Morality. Translated by Maudemarie Clark and Alan J. Swensen. Hackett, 1998

Rosetti, Christina. “Goblin Market.” From The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, One-Volume Compact Edition. Broadview, 2018, pp. 1615-1622

0 notes

Text

Adam Raised a Cain and Cain Raised a... Grendel?: Explorations of jealousy as the root of evil in the British canon

My shrink once told me that jealousy stems from a desire to protect what you perceive to be yours. I remember being caught off guard when I heard that, having previously thought of jealousy as, as I am sure most of us do prior to further reflection, the feeling that arises from watching other people enjoy what you wished you have. What the definition I was offered changes about this assumption is that it instills it with a very irrational, but very personal, sense of possessiveness, and it got me thinking about how jealousy in action across the stories we have read this term has manifested as a particularly interesting brand of evil. Jealousy as an emotion often spilled out, consciously or unconsciously, as violence and destruction against what the characters we read about have seen—rightly or wrongly—as being rightfully their own. This essay will explore at length how these various characters allowed for their possessiveness and jealousy to run afoul of reason, resulting in the chaos that drove their stories forward.

Going all the way back to somewhere between the tenth and eleventh centuries from what researchers can gather, one of the very earliest manifestations of jealousy as the leading cause of evil can be found in the epic poem Beowulf. Beowulf is exclusively a story of live action, with the events of the story unfolding in descriptions of the physical and material, and with no attention paid to the inner workings of our characters’ minds, their psyches, and their motivations. The result of this is that the reader, based on the few clues they are offered, are left to themselves to determine what maxims our characters are acting upon.

There are three villains present in Beowulf: Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the wealth-hoarding dragon (who distinctively reminds me of Jeff Bezos for some reason). The root of the dragon’s evil, and Grendel’s mother’s evil, are apparent on the surface: the dragon was greedy and hoards wealth that the humans want for themselves, and will protect his wealth with violence, and Grendel’s mother wants to avenge her son who was murdered by the humans, just as any mother would. Grendel himself is a little more subtle, but the reader is left with one major clue as to exactly what causes him to attack the humans in the first place:

…people lived in joy,

blessedly, until one began

to work his foul crimes—a field from hell.

This grim spirit was called Grendel,

lightly stalker of the marshes, who held

the moors and fens; this miserable man

lived for a time in the land of giants,

after the Creator had condemned him

among Cain’s race—when he killed Abel

the eternal Lord avenged that death.

No joy in that feud—the Maker forced him

far from mankind for his foul crime.

From thence arose all misbegotten things,

trolls and elves and the living dead,

and also the giants who strove against God

for a long while—He gave them their reward for that.

Grendel is personified, either metaphorically or physically, as a descendant of Cain’s; as a byproduct of the biblical character’s evil. Grendel arose from how the Lord punished Cain for his sin, and Cain’s sin, quite blatantly, was that of jealousy: He saw his brother, Abel, as receiving the love from God that Cain himself should have been receiving. Cain felt a sense of entitlement to God’s love, and when he did not receive it, was driven with jealousy to murder his brother so that more of God’s love that ought to have been his would have come his way; he was to have less competition. This passage quite literally frames Grendel as a creature born from the very first human sin after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden: an act of pure jealousy.

Grendel, therefore, seems to be inherently a jealous creature, but the reader also has good reason to see that he might have good reason to have acted the way he did within the confines of this story. Or, if not good reason, then at least, some reason: the Danes’ Heorot Hall was erected on the land Grendel previously inhabited, while he, “a bold demon who waited in darkness/wretchedly suffered all the while,/for every day he heard the joyful din/loud in the hall, with the harp’s sound,/the clear song of the scop.” While the narrator of the poem is making Grendel out to be a monster that acted solely out of hatred from humans, there is clearly something else going on here as well. Grendel watched from the shadows as the Danes built a noisy hall on the land he had called his own, and their celebrations and the beauty of human civilization surely must have been hard for him to witness in a similar way to how they affected Frankenstein’s creature, as they reinforced his sense of his own ugliness, loneliness and misery, now paired with the fact that his land was not his own anymore. While this may not exactly justify Grendel’s actions as correct, the reader, upon reflecting upon these details, may develop a deeper sense of sympathy for Grendel, as his evil was not unprovoked, but rather, a result of the recognition that something that was his was not anymore, and he was surrounded by constant reinforcement of the beauty of human civilization that was not his either.

Jumping forward a handful of centuries to The Canterbury Tales, we can find an interesting example of how a sense that something ought to have been yours, even with no evil intention present, can result in a whirlwind of chaos, violence, and eventually death. In The Knight’s Tale, Palamon and Arcite, while in prison, both fall in love with the only woman present, the unfortunate Emelye who certainly had not planned on getting dragged into this mess. Similar to the conception of jealousy at hand is the notion they are both regarding Emelye as something that ought to be theirs, when they both become smitten with her beauty and get it into their heads that they must escape prison and marry her:

…Venus, if it be thy wil,

Yow in this gardyn thus to transfigure

Bifore me, sorweful wrecche creature,

Out of this prisoun helpe that we may scapen!

And if so be my destynee be shapen

By eterne word to dyen in prisoun,

Of oure lynage have som compassioun

That is so lowe ybroght by tirannye!

The very sight of her, and the feeling of possessiveness that it drives into both men’s hearts, drives forward the rest of the action in the story, and at first, the longing for something they acknowledge as what ought to be theirs spills out into jealousy, and then violence, as Palamon and Arcite cease to see each other as friends and become obstacles to one another instead. Neither man had any claim to Emelye—she was, quite literally, the only woman around. But the singularity of their desires for companionship from the world outside of their prison, in addition to her beauty, gave them a sense like she was the only woman they could ever love. This infatuation was exclusively a byproduct of abnormal circumstances, and in no shape or form could they have made any claim that she was ‘theirs.’

The two are given the chance to battle one another, army and all, for her hand in marriage, ultimately resulting in Arcite���s death. Palamon gets what he wants at the end, at a cost he had not bargained for, providing us with a prime example of the destructive and sometimes deadly results of jealousy and possessiveness, especially insofar as these emotions can envelop us completely if not checked and can cause us to lose sight of everything else that is important in life outside of the singular focus of an intense desire.

John Milton’s conception of Satan is almost wholly motivated by jealousy, and of all the characters within the British cannon—if not all the characters out there—he perhaps signifies the most severe case of jealousy’s destructive powers taken to the their logical conclusion. Lucifer may have been the most beautiful and most loved of all the angels, but that still was not enough for him: God still existed, and God was still more perfect than he was. Lucifer waged a war against God, wanting to take his place that he saw as rightfully belonging to him. Obviously, as God is literally a being of infinite capacities, the war did not go the way Lucifer had wanted it to, and he was expelled from Heaven into the fiery pits of Hell:

…with ambitious aim

Against the throne and monarchy of God,

Raised impious war in Heavn’n and battle proud,

With vain attempt. Him the Almighty Power

Hurled headlong flaming from th’ ethereal sky,

With hideous ruin and combustion, down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In adamantine chains and penal fire…

he, with his horrid crew,

Lay vanquished, rolling in the fiery gulf,

Confounded, though immoral.

There is some profound irony in Milton’s conception of Hell not being something that Lucifer created, but rather, as a “place Eternal Justice has prepared/For those rebellious; here their prison ordained/In utter darkness, and their portion set/As far removed from God and light of Heav’n/As from the centre thrice to the utmost pole.” He is driving home the point that only God has genuine creative power—Lucifer could not even create his own Hell, it was handed to him as a prison. The implications of Lucifer’s lack of creative power is severe: because he cannot create anything on his own, he can only subvert and corrupt what God has already created. And so, he decided to take on God’s most perfect creation yet—Adam and Eve, the first man and woman—and corrupt them; since he cannot create any beauty of his own, he must cause ugliness where there is beauty.

The sense of jealousy returns both when, in Book III, Lucifer sees the Garden for the first time, and again, in book IV, when he sees Adam and Eve. Confronted with God’s beautiful creations, Lucifer’s sense of inferiority is reinforced, and fuels his desire to corrupt these wholly good works of God’s. He assumes the likenesses of a cherub and a snake, to deceive the Garden’s inhabitants, and is successful, in part, in his mission, when he persuades Eve to partake in eating the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. She in turn gives Adam the fruit to consume as well, and they are subsequently rejected from the Garden by God for their disobedience. But God is always one step ahead of the Devil, and he shows Eve mercy for her sins, rewarding her by making her the mother of all humanity. She is given a powerful legacy of creation on Earth, with her children destined to vanquish Satan, and providing her with such creative powers was another pointed blow to Lucifer in itself.

In the end, Lucifer is left with absolutely nothing. His demons are all turned into snakes by God, his plan to corrupt the humans largely backfired because they were forgiven, and he has been unable to build any sort of a legacy, yet alone anything as powerful as the one he had imagined for himself at the beginning; that would be so great as to overturn God’s rule. We are left with a picture of what jealousy will do to you if you act upon it uncontrolledly—you will have nothing, while all those you envied will move forward in peace.

One last text to conclude this exploration of jealousy is Sheridan Le Fans’s novella Carmilla. Carmilla, a vampire who was bitten and who became monstrous when she was a young woman, of the age where she would soon be married and start a family of her own, goes about pursuing victims that were all in the same place in their lives and who occupy the same place in society as she did when she lost her humanity. She has now been somewhat immortalized in the same physical form she had been when she became a vampire, and so, she still comes across as wholly desirable young woman: “‘She was very witty and lively when she pleased… the features were so engaging, as well as lovely, that it was impossible not to feel the attraction powerfully.’” But she will never be a human again, capable of love, relationships and starting a family, and so, she preys upon women who also meet such a description; who are lovely and would be considered ideal candidates for marriage. Her evil manifests itself as her taking away from them what was taken away from her. Especially considering the strict societal gender roles of the time, wherein a woman’s worth was determined by her relation to a family and mothering children, the inability to become the ideal woman she must have been raised her whole life to be has resulted in her exclusively choosing victims that would have occupied the role she thought was rightfully hers. Driven mad by jealousy, she retains what she thinks ought to be hers by not allowing others to have it either.

We can see from this that what makes Carmilla and Lucifer the most detestable of these villainous characters is that the subjects of their jealousy had done nothing to deserve any form of retribution simply for being in positions these two envied. Carmilla’s victims were a displacement of her own dissatisfaction with her lot in life, and the damage done by Satan demonstrated his sense of inferiority knowing there was a being out there that was more perfect than him. The young women Carmilla preyed upon, and God, the angels, and the humans, all did nothing to spite those who harmed them, and we see from this that jealousy can result in the most tremendous evil when deliberately and consciously aimed at individuals who had nothing to do with your own suffering, instead of dealing with your own suffering directly. With Palamon and Arcite, we also see a case in which Emelye, who was dragged into their strife, was harmed by their jealousy; but we are inclined not to judge those two as harshly as Carmilla and Lucifer because they lacked evil intention—they just also lacked the sensibility to realize that neither of them had any claim to this woman, and that their senses of possessiveness were wholly irrational. And while Grendel still did wrong, by all means, we can see that his jealousy in part springs from a sense of actually being wronged, with something that belonged to him actually having been taken from him, and so, because there is to some extent a personal vendetta against the humans because they are responsible for his plight, we may be inclined to have more sympathies towards him as well.

Most, if not all, destructive acts, can be tied to a desire to have something you think you ought to have, on some level; and stories like these do an excellent job at reminding us what can happen, intentionally or not, if we fail to critically analyze our own emotions as they arise by surrendering reason to be the slave of the passions.

Works Cited

“Beowulf.” The British Library, December 9 2014. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/beowulf.

“Beowulf.” In The Broadview Anthology of British Literature One Volume Compact Edition, 62-103. Peterborough, Ontario; Broadview Press, 2018.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “The Knight’s Tale.” In The Broadview Anthology of British Literature One Volume Compact Edition, 227-257. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2018.

Le Fanu, Sheridan. “Carmilla.” In Green Tea and Other Weird Stories, 378-439. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Milton, John. "Paradise Lost”. In The Broadview Anthology of British Literature One Volume

Compact Edition, 726-813. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2018.

0 notes

Text

Gay Shakespeare, but make it sad: Unity and honour in Sonnet 36

Sonnet 36

Let me confess that we two must be twain,

Although our undivided loves are one;

So shall those blots that do with me remain,

Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite;

Which, though it alter not love’s sole effect.

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love’s delight,

I may not evermore acknowledge thee,

Lest my bewailed guilt should do the shame,

Not thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

But do not so; I love thee in such sort

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report

From The Broadview Anthology of British Literature

Note: The in-text citations for the ‘Analysis’ section relate to the line numbers from this poem.

The thinly veiled homoerotic themes featured in Shakespeare’s body of sonnets appear to be of strong interest to modern readers, and for good reason: they serve as one of our earliest examples of an LGBTQIA+ writer who was not permitted to say outright how he was really feeling, and had to be careful to write poems which did not go against his authentic self while not offending the Protestant morality of his era. This theme displays itself more and less blatantly across pieces in sonnets that span a wide range of tones, with some being silly and lighthearted, others romantic, and a few, such as Sonnet 36, being downright heartbreaking.

The plot of the poem invokes an image of the narrator sadly explaining to his lover they must be extremely cautious as not to have their relationship discovered in order to avoid public backlash and the tarnishing of the lover’s reputation. While the two are one in spirit, this external pressure stemming from the homophobic reality of their times forces them apart; they are doomed to remain two distinct bodies sharing one love for each other, instead of the shared body, mind and love they would be publicly seen as sharing had they been married.

The rhyme scheme of the poem, like many of Shakespeare’s other sonnets, goes: A-B-A-B C-D-C-D E-F-E-F G-G. The four separate sets of rhymes break the poem down into four small sections, starting with an introduction of the situation and of the two main themes of the poem; which can be briefly summed up as unity versus division, and honour. The introduction informs us of the basic facts of the situation: our characters are secretly in love and they must take careful measures to preserve their relationships’ secrecy. It is briefly mentioned (but not thoroughly explicated) that our narrator has some kind of a tarnished reputation he feels he must bear alone; he wishes to remain separate from his lover as well in this respect. In the second section of the poem the first theme of unity versus division is developed, while the third section further expounds upon honour and the importance of reputation. Finally, in the brief conclusion, the narrator reassures his lover he truly loves him despite the hardships they will face.

In the introduction and section on unity, the language used is strongly fixated on the united figure they wish to be and the reality of the divide caused by their inability to publicly express their love for one another. While heterosexual couples, when married, were considered within Christianity to be one in flesh and spirit, he observes their ‘undivided loves are one’ (2) but ‘we two must be twain’ (1).

The origins of this concept of a married couple as one flesh date right back to the first book of the Bible; it constitutes the very definition of Christian marriage: ‘Therefore shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall cleave unto his wife, and they shall be one flesh’ (Genesis 2:24). Ironically, ‘cleve’ by our tongue is usually affiliated with a separation, but quite literally means ‘to glue together’ in this Biblical tradition. Terminological choices that dominate the first eight lines of the sonnet lament they cannot partake in being imagined as one physical form by their peers, focusing on the unity and duality that plagues their situation: ’by me be borne alone’ (4), ‘in our two loves there is one respect’ (5), and ‘in our loves a separate spite’ (7). This pressure does not take away from the love they share from one another, yet their predicament ‘steal[s] sweet hours from love’s delight’ (8), meaning the judgment forces them apart, pushes them into secrecy and robs them of time they ought to be spending together.

A stylistic device worth noting is the whole poem is written in perfect iambic pentameter, to the exception of a slight deviation present in the eighth line. The alliteration of the letter ’s’ in ‘steal sweet hours’ suggests you should slow down and emphasize all three words, highlighting the injustice these lovers are facing by having their time together cut short.

In the third section of the poem, the narrator returns to shame and honour. He tells his lover he ‘may not evermore acknowledge thee’ (9); pretending to not even recognize him as an acquaintance if he sees him in public; as he perceives his ‘bewailed guilt’ (10) to be so strong it will bring shame upon his lover even if they are seen as mere friends. He implores the lover to return the favour and pretend not to know him as well under the public eye, or the lover will have ‘honour [taken] from thy name’ (12). As the previous section focused on the narrator’s true, subjective feelings, this section ignored them completely and presents itself objectively. He knows he cannot allow for love to affect his lover’s safety. Clearly the matter is weighing on him tremendously, but he has been forced to set his own concerns aside, acting sadly rational about something as irrational as romance to protect his lover.

The last two lines concluding the poem combine the emotionally attached and detached elements as he reassures his lover he is the subject of his ‘good report’ (14), and that his lover must not get so caught up in the pains the technicalities of their relationship cause that he forgets why they love each other in the first place. And so, in fourteen brief lines, Shakespeare has given us quite a complete story about the burdens people of marginalized sexual identities faced in the Elizabethan era when they had to simultaneously face the romantic and the pragmatic, contextualized against the religious norms of its time; resulting in a poignant and tragic piece of both literature and history.

0 notes

Text

What happens to women who eat apples: Comparative treatments of the Fall in 'Goblin Market' and Paradise Lost

Passages Referred To

…and to my memory

His promise, that thy seed shall bruise our foe;

Which, then not minded in dismay, yet now

Assures me that the bitterness of death

Is past, and we shall live. Whence hail to thee,

Eve is rightly called, mother of all mankind,

Mother of all things living, since by thee

Man is to live; and all things live for Man.

To whom thus Eve with sad demeanour meek.

Ill-worthy such title should belong

To me transgressour; who, for thee ordained

A help, became thy snare; to me reproach

Rather belongs, distrust, and all dispraise:

But infinite in pardon was my Judge,

That I, who first brought death on all, am graced

The source of life; next favourable thou

Who highly thus to entitle me vouchsaf’st

Far other name deserving. But the field

To labour calls us, now with sweat imposed,

Though after sleepless night; for I see the morn,

All unconcerned with our unrest, begins

Her rosy progress smiling: let us forth;

I never from thy side henceforth to stray,

Where’er our day’s work lies, though now enjoined

Laborious, till day droop; while here we dwell,

What can be toilsome in these pleasant walks?

Here let us live, though in fallen state, content.

John Milton, ‘Paradise Lost’

Book 11 156-180

Days, weeks, months, years

Afterwards, when both were wives

With children of their own;

Their mother-hearts beset with fears,

Their lives bound up in tender lives;

Laura would call the little ones

And tell them of her early prime,

Those pleasant days long gone

Of not-returning time:

Would talk about the haunted glen,

The wicked quaint fruit-merchant men,

Their fruits like honey to the threat

But poison in the blood;

(Men sell not such in any town):

Would tell them how her sister stood

In deadly peril to do her good

And win the fiery antidote:

Then joining hands to little hands

Would bid them cling together,—

“For there is no friend like a sister

In calm or stormy weather;

To cheer one on the tedious way,

To fetch one if one goes astray,

To lift one if one totters down,

To strengthen whilst one stands.”

Christina Rossetti, ‘Goblin Market’

543-567

An unsuspecting and disobedient woman being offered a fruit by a demonic figure, biting off more than she can chew. A wholly good figure who steps in on behalf of the fallen woman, acting solely out of love and charity, offering her a redemption that she did nothing of her own accord to deserve. The legacy of the mother’s sins that is passed on as a stern warning through the children. Such are among the many parallels between the plight of the biblical Eve, as presented in John Milton’s epic Paradise Lost, and the unfortunate Laura of Goblin Market. One may be able to understand Laura’s character and plight as a re-working of Eve’s fall from the Garden, with religious undertones present but concealed, and a gracious sister filling in the role of the divine spirit that provided Eve with the opportunity to triumph over the Devil. Starting from this position, this paper will examine both the similarities and discrepancies between these women’s misadventures in order to arrive at a comparison of Eve and Laura’s respective fates.

Eve’s tale requires little recapitulation: Perfectly content in the Garden of Eden with Adam, she has been ordered never to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. But alas, that pesky Satan disguised himself as a snake, and persuaded Eve to partake in the consumption of the apple. Subsequently, she and Adam are banished from the Garden, and are only to return to God’s kingdom after their physical bodies perish on Earth. The original account of the Fall ends with their exile, and God’s most interesting prophecy for the devil, wherein “I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel”. What sets Milton’s interpretation apart from the original account in Genesis, and what, at least to the author of this paper, truly renders it a powerful elaboration of the original story, is that Milton greatly expounds upon this small prophecy, by allowing for the angel Michael to show Adam and Eve much more completely what their fates and future will be—specifically by showing Eve exactly how she is to enact her revenge upon the Devil. And what a revenge! Eve is made the mother of all humanity; with her offspring to survive and thrive for millennia, creating beauty and joy on Earth while all the Devil can do is corrupt and invert what God has already created. At this point, the earlier supposition that Eve did nothing to deserve her own redemption may require more unpacking. While the Devil certainly helped to lead Eve astray, the act she partook in was an exercise of her own free will, and a violation of one of the only orders God had given to them. In fact, she contributed to the digging of her own grave by offering the fruit to Adam as well. After her sin, she performed no redeeming act of her own, and simply by God’s good graces was she permitted to live the life she did, as the mother of all humanity.

Goblin Market deviates from Paradise Lost in that there are many Goblins, as opposed to one snake; and many fruits, as opposed to just the apple. But the parallels are clear, as the Goblins act as a unified whole, trying to push humanity into a fallen state, and the fruits are all of the same nature as well. The apple, additionally, is the first of the Goblin’s fruits mentioned. Poor Laura, like Eve, shows an interest in the fruit, and is goaded by the demonic figures to consume it. Her desperation is curiously reinforced by the fact that, as she had no money on her, she begged the Goblins for an alternate way to pay for the fruit, and does so by offering them a piece of her own body: a lock of her hair. While there is no intervening divine force in the story, there is a sister of an extremely ascetic character who is able to step in and offer her sister salvation. Lizzie ventures into the realm of the Goblins, and as hard as they try to force her to consume the fruit, they are unable to, and the fruit of the Goblins loses its corrupting influence. The fruit now assumes a Eucharist-like nature; as Lizzie implores her sister to “hug me, kiss me, suck my juices/Squeezed from goblin fruits for you/Goblin pulp and goblin dew./Eat me, drink me, love me;/Laura, make much of me”, her sister is saved by consuming the ‘flesh’ of her sister. Laura, like Eve, while not wholly deserving her own downfall, also created her situation for herself as the result of her own free choice, by not being obedient to the important teaching of not eating the Goblin’s fruit, and performed no further action upon consuming it that made her more worthy of rescuing. She simply had a sister who loved her, as Eve had a Creator who loved her, and both loving figures kept those fallen ones alive.

One last point of interest prior to turning to a close comparison of their destinies might be the role of fertility between both texts: Eve is made the mother of all humanity in order to enact revenge upon the devil, while Laura, prior to her sister’s actions, was to be punished for her sin by not being permitted to have children. The nasty effects of the goblin’s fruits upon Laura were that they caused her to age and wither rapidly; like the unfortunate “Jeanie in her grave,/Who should have been a bride; But who for joys brides hope to have/Fell sick and died/In her gay prime”. The implied tragedy is that these young women, who were supposed to marry and have children, were robbed of their age and beauty and fertility that made them valuable, and so, were to die incomplete. Fortunately for Laura, she had a sister who knew what to do to save her, and she was able to go on to have children; in the absence of such a sister, however, Laura surely would have faced the same plight as Jeanie. So while both women become mothers at the end of their stories, the implications of motherhood are quite different for both of them.