Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The White Man: Identity as Opposition in 19th century America

Take up the White Man's burden-- Send forth the best ye breed-- Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives' need; To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild-- Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.

- The first stanza of The White Mans Burden by Rudyard Kipling from 1899.

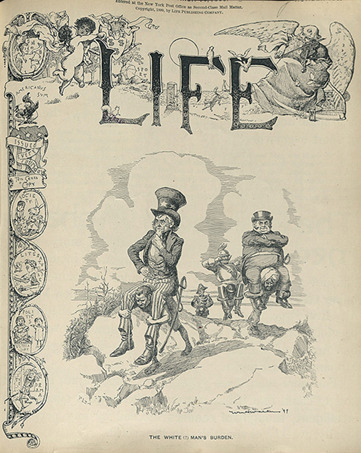

1899’s “The White Man’s Burden!” by William H. Walker. The figures of Uncle Sam and Kaiser Wilhelm being carried on backs of subjugated people in the Philippines, India, and Africa. These figures have always been depicted as Caucasian, literal figures of white peoples. This and a series of illustrations are based off a famous poem by a Britain in reaction to American takeover of the Philippines, presenting the White Mans Burden as a thankless but necessary job in “civilizing” the savage, “Half demon half child” people. Source.

It is odd, as a white person, to hear news of a White Power movement growing in America, specifically among young white men in the right side of the political spectrum. I can’t help but ask, when was power taken from white people? We’ve always been the majority in America, dominating popular culture to a problematic extent. We’ve also dominated education, populate the highest priced residential areas, and make up the richest people in the world (though that is changing in all aspects). So, it’s strange to have watched people protest in Charlottesville with dollar store tiki torches, The president advocate for extreme immigration control, and that same president by advised by a major white nationalist advocate (Who likely influenced the prior decision). I ask again, why do whites need more power? To reference the poem above, does the white man carry a burden?

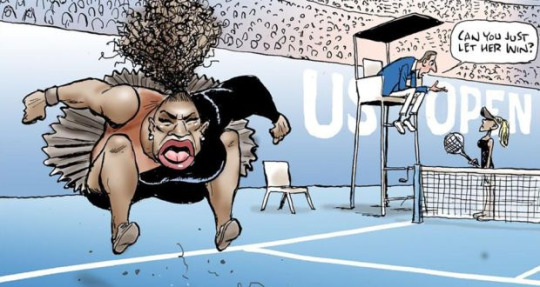

As American society begins to grip with its past, full of racism, colonialism, exoticism, and taking advantages of minorities, we see this sudden push back from this group of people who advocate for “white power”, more specifically, to defend this “white power”. Throughout their debates, we find references to “white genocide”, through immigration, racial based science, and eugenics, along with linking minorities (specifically the colored minorities) to higher rates of crime (Clark). They participate in this “othering” of “non-white” races, which finds an uncomfortable connection within the very history they (and society as a whole) debate with.

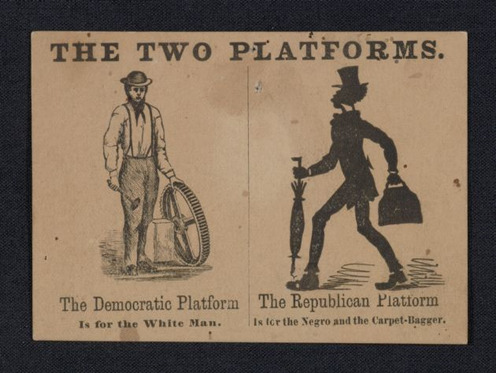

1960s Century propaganda for the Democratic party, illustrating the Democratic party as the respectful, hardworking White Man and the Republican Party as this cartoonish mockery of “the Negro” as a “Carpet-Bagger” (a term for traveling swindlers). Several similar posters can be found, with the same slogan. It should be stated that this is before the Democratic and Republican platforms switched platforms with each other around the early 20th century. Source.

As American began to find itself in the 19th century, meaning its identity along with the fact the nation had only recently been created, we find the identity of the “White” individual being emboldened by the othering of those races they considered “savage”. The figure of the white man is presented as this master of the nature, this excellent survivalist, who at the same time astounds audiences with his charisma and charm, all the while civilizing the wild world of the American West. It’s outlined by Minstrel Shows, Public displays of “History” like Buffalo Bills Wild West Show and to a lesser extent those of P.T. Barnum, and the depictions of both the white man and the Native American that find themselves in 19th century culture. To illustrate this plainly, look at “The White Mans Burden!” once again, the white man is carried forward only under the mistreatment of the Colored while at the same time this action being called his “burden”.

At the same time all this is happening, this identity allows other marginalized people, particularly the Irish, to integrate into society more easily. The identity of “the White”, in place of nationality, gets solidified in the 19th century as an aspect of being American by “othering” the savage, the minority.

An 1899 Lithographed Advertisement for William H. West’s Big Minstrel Jubilee, Carrol Johnson is depicted in his natural state and In black face. Notice the clear difference in how he carries himself between the two depictions. Source.

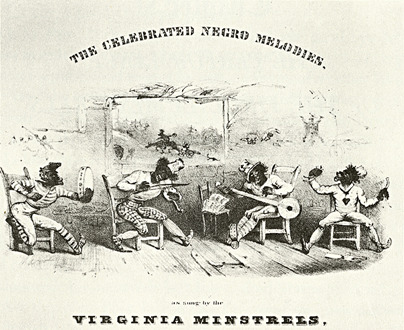

In the beginning of the era, we see both at the same time minstrel shows and minstrelsy in itself become immensely popular (oddly enough among the Northern states) and the westward expansion of America happen leading to Native American displays like Barnum’s and Buffalo Bills Wild West Shows (along with Medicine Shows offshoot). Both participate in the same type of “othering”, the colored (or rather those masquerading as the colored) as a show, a display for the white audiences to look at and place themselves in opposition to.

The minstrel show started, preceded by what were called “Ethiopian delineation” which stole black culture, around 1828 with Thomas D. “Daddy” Rice creating the character of “Jim Crow” (which was based off a young, disabled black stable hand of the same name). Typically, it consisted of a white man or men, with their faces blackened by shoe polish, performing a series of skits, comical speeches, musical renditions of slave songs in mock dialect, playing instruments, and “Negro” humor (Toll).

It boomed in the entertainment hungry, blossoming cities of the 1820s, “Working-class whites flocked to minstrel shows, where they could define their whiteness against the drama of blackness” (Browden 50). To quote Robert C. Toll of the American Heritage Magazine, “The “Jim Crow” song and dance, observed writer Y. S. Nathanson in 1855, “touched a chord in the American heart which had never before vibrated.” It brought black culture to white Americans.” It at the same time allowed white Americans to other the black figure, positioning themselves as the “civil” White opposition to the cartoony, caricature the minstrel show performers showed. It presented the black figure to an audience, that would have little true interaction with them:

The Northern white public before the Civil War generally knew little about black people. But it knew that it did not welcome blacks as equals and that it did enjoy watching minstrels portray the “oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and comicalities of that Sable Genus of Humanity.” With their ludicrous dialects, grotesque make-up, bizarre behavior, and simplistic caricatures, minstrels portrayed blacks as totally inferior. Minstrels created two sets of contrasting stereotypes—the happy, frolicking plantation darkies and the foolish, inept urban fools (Toll).

Both stereotypes that these Minstrel shows presented, neither the truth of these people, were more digestible and thus, more easily universally “othered” as inferior. “Whiteness is defined in opposition to blackness, which becomes performative and ridiculous”, the two become polar opposites to each other (Browden 49). One is seen as the civilized race, the clear White, and the other is seen as the lazy, silly black.

In this opposition of the White and the Black, we oddly find this integration going on at the same time of separation of race. During this time, Irish Immigrants would be in the same niches of African Americans, being compared and put on the same unequal level as them.

However, these shows of race offered immigrants “the chance to develop an identity that downplayed their own “foreign” ethnicity and offered them an opportunity for a common, Americanized identity in opposition to blackness” Simply put, Minstrelsy as a whole “made a contribution to a sense of popular whiteness among workers across lines of Ethnicity, religion, and skill” (Browder 50). It created this highly specifically American white identity (Some could say it becomes the American identity itself), that enabled the immigrant to integrate themselves more easily into the new America as it lined its sights on skin tone rather than nationality.

Yet, this came at the price of denying Black Americans the same courtesy, as Minstrelsy refused to work in both directions. The White could mock the black by becoming them temporarily, however the Black were ridiculed. The White American could act Black, however the Black American could not “act white”, as it was put for the White was seen as the norm, the goal.

A group of Native Americans (assumed Sac, Fox, and Iowa personages) Barnum had perform at his American Museum to perform dances and “war-like” reenactments. He is recorded as calling them “a lazy, shiftless set of brutes” Source.

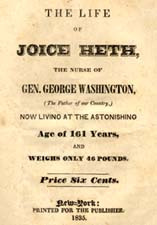

I would be remised to talk about popular displays of race and entertainment (along with arguments of authenticity) without talking about P.T. Barnum and his American Museum. He displayed various African Americans as freaks, like Joice Heth or “What Is It?” who was malformed African American man presented as the link between man and ape, although he wouldn’t allow African Americans into his museums until the 1860s (Browder 56). He offered a similar role Minstrelsy offered to the white audiences, a chance to create White identity in opposition to Blacks he presented as “freaks” and “oddities”. Additionally, Barnum, before Buffalo Bills Wild West Shows would come onto the scene, displayed Native Americans at his museum, presented simply as themselves which was enough to create opposition to the population that would have little interaction with Indians in a non-performance, spectacle based space.

In 1843, he had those Native Americans pictured above perform at his museum for his audiences. He stated, “These wild Indians seemed to consider their dances as realities” referring to the Indian performers refusal to understand the “performative nature of their lives” (Browder 57). Later that same yet, he would present to 24,000 spectators in New Jersey a “Grand Buffalo Hunt” where a “white man dressed as an Indian chased a herd of yearling buffaloes across the Hoboken race course” (57). In this instance, “the national drama of westward expansion was reduced to a child-sized joke”, as Laura Browder puts it.

Later in 1863, He would group up the most popular Indian chiefs in the country in one area, from their peace conference with President Lincoln. One of those chiefs was Yellow Buffalo, famous for his battles, “During the show, Barnum would make a great pretense of saying respectful and admiring things about him, put his around him and so forth….while his patter (which Yellow Buffalo couldn’t understand because he didn’t speak English) described all of his blood-curdling atrocities” (Stewart).

Finally, by 1884, He would present the “Grand Ethological Congress of Nations” (after his days of Museums and into his Circuses), “in which he presented all the known world’s “uncivilized races” and “savage and barbarous tribes”, including a group of North American Sioux people amongst the Zulus, Polynesians and Australian Aborigines” (Stewart). Needless to say, Barnum pictured American Indians as the popular culture did, savage.

He presents these displays of Native Americans as he did his Black American displays, as oddities that find themselves outside of the White, “civilized” society. These “performances” offered yet another chance for the White populace, including immigrants, to define themselves by their Whiteness. “Many immigrants first saw Indians at the museum; it was here that they might affirm themselves as Americans viewing the vanquished subjects of their newly adopted nation” (Browder 57). They hold themselves in opposition to the “wild Indians” and African Americans (Depicted as semi human or mystically old). Barnum offers a in between for Minstrelsy and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, this performance of exaggerated caricature of both Black Americans and Native Americans while at the same time trying to perform in this authentic, historical context.

A poster for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (and Congress of Rough Riders of the World). The description reads “Representing various tribes, Characters and Peculiarities of the wily dusky warriors in scenes from actual life giving their weird ward dances and picturesque style of horsemanship”. The American Indians are characterized as this odd mixture of earthy colors, in these wild and savage positions as they attack a wagon train (based on a real life event) reflecting cultural thought of the Indian as a war-seeking people. The Whites are depicted as innocent, or respectful like Buffalo Bill, sitting on his horse evenly in comparison to the “rough rider” way (which even the horses seem scared of). Source.

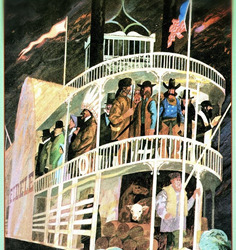

In the same vein, Buffalo Bills Wild West Shows (and later Medicine Shows after these shows lose popularity) depicted the American Indian as another opposite to the “White” identity (Although not entirely on the surface level). Buffalo Bills Wild West Shows began in the early 1880s, when these displays of Indians and Buffalo Hunts had become acts of nationalistic, solemn pride rather than the comical acts of Minstrelsy and Barnum’s displays (though it almost replaced Minstrelsy to a point). Buffalo Bill, his real name being William Fredrick Cody, authenticated these shows as being historical in nature, in truth they were recent enough that the lines between reality and history became thin enough to affect eachother (Browder 58).

These shows of “historical events” would present various acts, “The show's constantly changing format consisted of several exhibitions and competitions involving activities such as riding, hunting, shooting, and dancing” along with reenactments of famous battles or particular events, such as the famous “Attack on Settler’s Cabin” where Indians “played” themselves (in this odd act of authenticity against the cultural thought of the Native American) while “white performers would defend a homestead of women and children from native raiders” (White 35-36). These shows started more basic, with basic shooting demonstrations of Annie Oakley, but as the shows became more popular they became more violent, more “loud”, “As one reporter wrote "[t]he more there was of banging pistols and scurrying Indians, the better apparently the spectators liked it" (36).

While these shows were no where near the level of mockery and caricature the likes of Minstrelsy was to the native populations (along with other minorities later allowed to perform), it still portrays a divide and opposites between White and Colored peoples. It is the fantastical version of the Wild West History, that the easterners likely would have never interacted with other than through other people (who would likely be White). The Wild West became Buffalo Bill to eastern audiences and American Indians became walking advertisements for the show (along with being used later in Medicine Shows as mascots for authenticity). Joy Kasson says, In her book overlooking the entirety of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West:

“In its crude form as a dime novel or melodrama, and in its more sophisticated form in the animated outdoor drama, this Wild West story reached for the power of myth. And to attain this mythic level, it required an enemy, a counter-force against which the hero displayed his virtues. American Indians were consistently cast in this role” (161).

The white actors would be displayed as strong, skilled, outdoors men, holding shooting shows, rounding buffalo, acting as the heroes in historical reenactments saving captured women, and defeating those the popular culture considers “savage”. Meanwhile, the American Indian actors, being primarily from the Ogalala Sioux, would be presented doing war-dances, only participating in specifically “Indian” activities, and the fallen in fake battles.

While Buffalo Bill might not have meant the view of them to be so, excuse the phrase, Black and White, it would easily be digested that way in the eyes of spectators. “Stage actors can walk away from the parts they play, but the Wild West confounded distinctions between “reality” and “representation”, and just as Cody was considered a “real” hero because of his dramatic enactments, the American Indians in his company were identified with the villainous roles they played in the show” (Kasson 162). After all, the white man cannot be the loser to the audience of whites, it simply wouldn’t be satisfying.

Kathy White displays this definition of identity through opposition along with the division the White and the Colored have in these shows:

Riding exhibitions and competitions played a key role, although winning and losing depended on the day because competitions were debatably rigged; one Chicago Tribune article boasted that the American cowboy always beat "them all" (Indians, Mexicans, and other foreign performers that were later invited into the show).

Indeed, the definition of identity is often sought in its opposite. What is "right" is what is "not wrong" and in this case, what was "civilized" was supposedly that which was "not savage." One way to be delineated as "not savage" and, therefore, "civilized" was to have a relationship with technology. Correspondingly, Warren notes that the most technological feature of the show, the shooting competition, always saw white Americans victorious over Indians and Mexicans (36).

Through this “othering” of Native Americans as lesser, inferior to the White performers, it creates this affirmation of the “White” identity as higher. Granted, Kathy White also lays out points where Indians were often praised for their strength, their dexterity, ability to ride, and unique customs, however those are all put in opposition to the White, nevertheless. Of course, the Wild West is more complex than it is presented, however the history of it is written by the White victors, and the identity of the “White” is cemented by opposition.

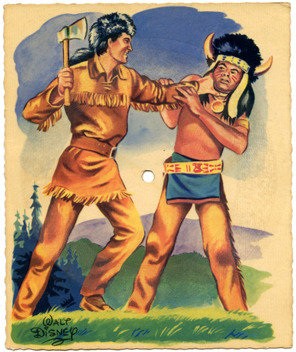

The cover of a Phonoscope produced by Walt Disney in France titled “La Ballade De Davy Crockett”, depicting Davy Crockett fighting a Native American. The figure of Davy Crockett has become ingrained into America history as a true American icon, to the point a racoon tail cap can be directly tied to him without any other context. Source.

To summarize the cultural image (and ideal) of the White American, we can look no further than Davy Crockett. This performance of whiteness, which exists majorly in opposition to non-whiteness, becomes somewhat tangled together with the performance of being American. From his beginnings as a popular icon in the 1830s, Davy Crocket employed “a combination of autobiography and melodramatic performance to craft an image of himself as an archetypical American, one whose stature depended in part on his ability to keep blacks and Indians in their places” as Laura Browden states. She captures an odd element that repeats in these narratives of the frontier, specifically in context of the White Man, this mixture of Historical context and fantastical exaggeration of prowess. Browden continues, “Crockett’s version of Americanness emerged in opposition to the other; his national identity came not from ancestry, blood, or essence but from his ability to conquer the land and its original inhabitants” (51). Crockett creates this uniquely White American image, that summarizes what Minstrelsy, Barnum’s displays, and Buffalo Bills Wild West Show all demonstrate below the surface.

To expand on this, it is no coincidence we see Crockett also align himself with people like General Andrew Jackson, who owned more than one hundred slaves, “bought with money gained from speculation on land from Native Americans, built his political reputation on his role as an Indian Fighter” (51). The identity of the White American comes from this violent, oppositional force built on this image of the wilderness taming man, who at the same time tings on animalistic qualities (primarily that of raw, brutal strength) that are accepted simply because of his skin tone.

He presents as the white primitive, compared better to the Indian barbarians and the Black savages. Crockett’s status as a white American “was set off against a background of inferior others”, boasting about boiling Indians for medicine for his pet bear, being able to swallow “a nigger whole without choking if you butter his head and pin his ears back”, along with describing Mexicans and Cubans “as “degenerate outlaws,” Indians as “red niggers”, and African Americans as “ape-like caricatures of humanity” (Calling back to the Barnum display of “What is It?) (52). Davy Crockett created, paraded, and summarizes these concepts of Whiteness and Americanness as one null category, and that Identity existing only in opposition above others.

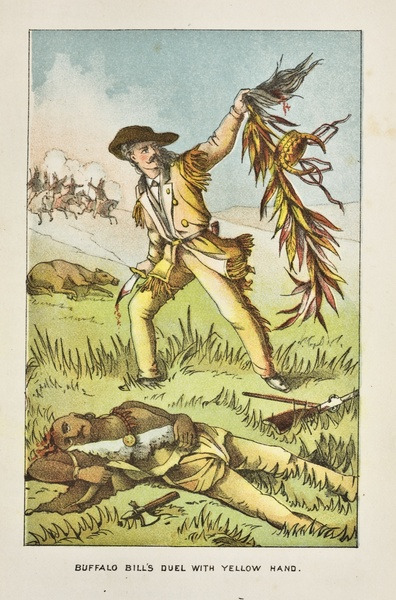

“Buffalo Bill’s Duel with Yellow Hand” by James W. Buel from Heros of the Plains, or, Lives and Wonderful Adventures of Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill ... and Other Celebrated Indian Fighters ... Including a True and Thrilling History of Gen. Custer's Famous "Last Fight" from 1881. Buffalo Bill is seen the victor of his 1876 duel with Hay-o-wei of the Cheyenne, he reenacts this event in his shows later. He holds the scalped hair and feathers of Hay-o-wei, an odd allusion to a practice Native Americans did. Source.

The identity of the White American in the 19th century mostly thrives in Opposition to other races, of skill, of morality, of humanity, and of civility. The theatrical tradition of Minstrelsy, The Displays of P.T. Barnum of both blacks and Native Americans, along with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show all participate in this othering, intentional or not, of race ignoring nationality and blood. While it offers Immigrants an easier integration into American society, it also participates in this unkindness towards the “colored” peoples. Black Americans are depicted as lazy, frolicking slaves or foolish urbanites all the while their culture is stolen and commodified for the White identity to laugh at. Native Americans have their culture commodified as well, used as entertainment and exoticism-focused exhibits, along with having to reenact brutal battles and deaths where they are always the victim. Davy Crockett stands as the figure of ideal White Americanness in opposition to all these stereotypes, this strong, nature conquering frontier man with condoned animalistic traits mixed with this racial oppression of the most American people and Blacks.

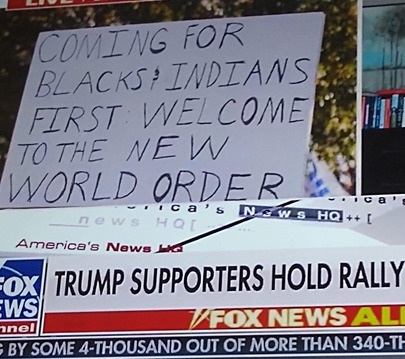

A photo of a sign displayed at a Trump Rally being reported on Fox News, reading “Coming for Blacks & Indians First: Welcome to the New World Order”. This “New World Order” is uncomfortably mirroring Antebellum Age America, zeroing in on the most oppressed races in the era (Not to downplay the oppression all other “non-white” races received). Source.

This growing White Power movement in America finds itself uncomfortably close to the 19th century’s ideals of the White American. Perhaps it is no coincidence though. Is the power the White frontier man had the “White Power” they to reclaim? This perceived strength and domination over the land and its natural people, all the while being seen as the most skilled, civilized, and powerful race all at the same time? Perhaps, moreso, as the percentages of races in America begins to balance more, they begin to see these fears of losing more power, that is more influence over culture than the “power” they already perceived they lost during the 20th and 21st century (perhaps by the movement to remove Antebellum age statues of Slaveowners). I state again, as a white individual, what power have white people lost that isn’t one that we didn’t deserve? If coming to terms with our mixed, racism-tinged past is a loss of power then, it is a loss of power in exchange for further equality.

Browder, Laura. “Staged Ethnicities: Laying the Groundwork for Ethnic Impersonator Autobiographies.” Slippery Characters : Ethnic Impersonators and American Identities, The University of North Carolina Press, 2000, Pgs. 50-51, 56-58.

Clark, Simon. “How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics.” July 1, 2020. Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2020/07/01/482414/white-supremacy-returned-mainstream-politics/

Kasson, Joy K. “American Indian Performers In The Wild West” Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History, Hill and Wang, 2000, Pgs. 161-162

Stewart, Donald Travis. “P.T. Barnum and the Indians.” November 18, 2013. Travalanche, https://travsd.wordpress.com/2013/11/18/p-t-barnum-and-the-indians/

Toll, Robert C. “Blackface: the Sad History of Minstrel Shows.” Edited with Introduction by Edwin S. Grosvenor, American Heritage Magazine, Volume 64: Iss. 1, 2019 (Republish of a 1978 Article). https://www.americanheritage.com/blackface-sad-history-minstrel-shows

White, Kathyrn. “"Through Their Eyes": Buffalo Bill's Wild West as a Drawing Table for American Identity.” Constructing the Past, Illinois Wesleyan University, Volume 7: Iss. 1, Article 8, 2006, Pgs. 35-36. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1079&context=constructing

0 notes

Text

There is Joy in Simplicity: 19th century Optical Toys

A late 19th century advertisement for the Stereoscope. It advertises the ability to be “Around the World in 60 minutes” reflecting the educational quality people believed the Stereoscope to have. Source.

I have become engrossed in the world of Yo-Yos lately. This little hunk of plastic with the name Duncan painted on the side, flying through the air on a string. By itself it seems so perfectly simple, however the world of Yo-Yos is deeper than one would think. For instance, there’s several different types of Yo-Yos with their own advantages and disadvantages based on their material and shape. While a Yo-Yo may seem like a simple toy, they also demonstrate a humans ability to learn reflexes. At first, I could barely get the Yo-Yo to come back up but after weeks of continued use I can shoot a dog across the wooden floor of my mother’s kitchen. Toys in a society are truly significant, because they represent what that society wants the young to learn or what they themselves want to play with. They are a form of experimentation.

Just as the yo-yo represents a learning of reflexes, the toys of 19th century America reflect the societal obsession with illusion and vision. Granted, people of the 19th century already had stuff like dolls (which I would argue is still related to vision of the human form), wooden tops and yoyos, dominos, balls, and all other means of play, but the late 19th century sees a boom of vision-based toys. We see the kleidoskope, the thaumatrope, the phenakistoscope, the stereoscope, the zoetrope, and the praxinoscope emerge as these fun little practices in vision. The early hints of film, the basics of animation, the play of illusion all appear in this era.

These toys exist as echoes of the 19th century American societal interest in deception, vision, and representation of self. In the early 19th century, the American faced challenges of identity, the crowd, later on they faced the mass societal grief and crisis of war, the camera as a view of reality, and the concept of the showman like P.T. Barnum, going into the late years of the era we see the early hints of film come out and the concepts of reality. Throughout the 19th century we see visions-based gadgets appear as supplements to the already ongoing discussions of view. Toys like the kaleidoscope, the thaumatrope, the phenakistoscope, the stereoscope, and the zoetrope and praxinoscope all represent a growing societal interest in vision and experimentation throughout the 19th century.

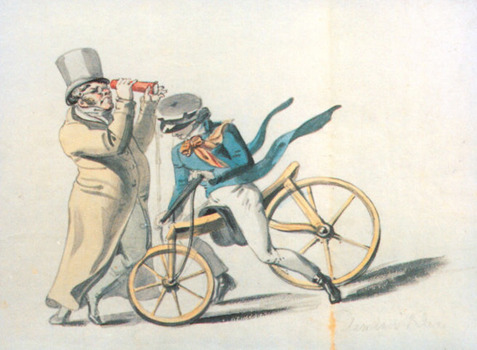

An 1818 illustration titled “Human Nonsense”, the man in the top hat is so entranced by the kaleidoscope, he doesn’t notice he’s walking directly in front of a bike. The Victorians had what Is now called a “craze” over kaleidoscopes as they allowed exploration of vision. Source.

The first optical toy to be invented in the Victorian age was the Kaleidoscope in 1816, by David Brewster, who we will see appear again. Jason Farman of Atlas Obscura describes the 19th century kaleidoscope design as, “made from a range of materials, such as tubes made of brass with embellishments of wood or leather or those cheaply made of tin. The base of the tube was typically filled with broken pieces of glass, ribbons, or other small trinkets.” When viewed from one side, the other would appear as a range of fantastical colors, patterns, and shapes. It almost immediately gained massive popularity, amongst both children and adults, scientists, artists, and industry professionals. Scientists “found it useful as a tool to visualize massive numbers” while artists and industrials used it “for patterns on china, paper, carpets, floor-cloths, and other fabrics” (Farman).

It was experimentation in the role of the eye in light, and shape, along with the illusions of beauty, or reality, when viewed close with a magnifier. Truthfully, some people felt betrayed when they found out what was inside of a kaleidoscope, R.S. Dement, a playwright, writes he was “deceived (as a child) into believing that what he saw was at least the shadow of something real and beautiful, when in truth it was only a delusion” (Farman). However, this only further intrigued some of the Victorian viewers:

These new visual tricksters fed into the fascination in the deficits of the human eye and how it could be misled. As people began understanding human vision differently because of these objects, people also began seeing the world through machines like trains, moving walkways, and steamships (Farman).

While the kaleidoscope is simplistic, it is not to be denied it is important as a starting point for the 19th century conversation on vision. A tube that presents to the viewer an illusionary range of symmetrical colors and patterns, created by broken glass, ribbons, and random scraps.

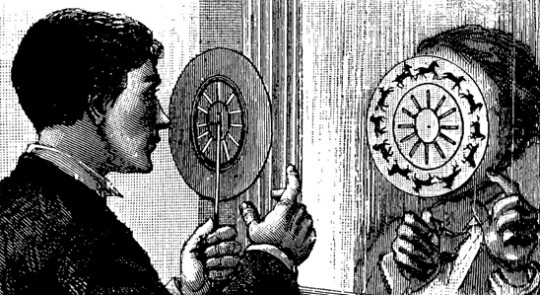

Vignette by George Cruikshank from Philosophy in Sport, 1827. Source.

The next optical toy to appear was the thaumatrope, appearing in the mid-1820s (when it was first published) by John Aryton Paris. The history of the thaumatrope is a mixed and complex mess of early 19th century scientific figures making a bet, including John Herschel (A popular astronomer), Charles Babbage (A mathematician who made the calculating engine), and David Brewster, however it stands clear as a true foundation of visual interest (Herbert). As much as I talk it up, the toy is extremely simple. It consists of a piece of cardboard with two strings on each end, with a picture on both sides (the classic example is bird on one side and a cage on the other) and when the user twists the strings fast enough the two images appear to become one (The bird appears inside of the cage). The same effect had been created by spinning a coin previously, however the thaumatrope was the first to give “the phenonium a scientific explanation and a device produced to be sold as a popular entertainment” (Gunning 499).

Bird-in-Cage Thaumatrope, the classic example and believed to be the first thaumatrope image created as an example, by Dr. Fitton. This depiction pictures the expected result of twisting the strings. Source.

While it is basic, its an extremely effective toy for teaching a core concept of the 19th century. There is flaw in the human vision, or moreso, the human vision has depths and conditions. From 1827’s Philosophy in Sport by Paris, “I will now show you that the eye also has its source of fallacy” says “Mr. Seymour” as he operates the device (501). Its simplicity allows there to be no questions about interference from the toy’s design, there is no mirror, or screen, or other window the viewer is looking at the toy at through.

“We can operate it and understand its process. But the image it produces is not fixed in space, embodied in pigment or canvas; it occurs in our perception. Yet while it may be defined as a subjective image, taking place through our individual processes of perception, it is not a fantasy or, in a psychological sense, a hallucination” (513).

There is simply vision, and the effect of the lasting image (called an afterimage) the human eye creates with the reality the user is the sole reason the illusion continues. Tom Gunning captures perfectly what the Thaumatrope meant as a foundational toy, “This device introduces to the Victorian era a new class of images simultaneously technological, optical, and perceptual” (500). It is the perfect device to start the 19th century with a magical simplicity that allows the user to experience illusion in their own hands through natural processes of the eye.

An illustration depicting a person using the phenakistoscope. Of course, it’s impossible to depict the movement accurately in a drawing. Source.

Later, in 1832, the phenakistoscope was “simultaneously invented…by Joseph Plateau in Brussels and by Simon von Stampfer in Berlin” though other concepts were in the works at the same time (“Phenakistoscopes (1833)”). The so called “parlour toy” is a cardboard disc on a handheld stick with an outer circle of images and an inner circle of slits which the viewer would look through. The “trick” of the toy is to spin it while looking through the slits into a mirror, where the images on the outer circle jump to life in animation through the distortion and the flicker of light as the disc moves. “The scanning of the slits across the reflected images kept them from simply blurring together, so that the user would see a rapid succession of images that appeared to be a single moving picture” (“A Short History of the Phenakistoscope”). Its one of the earliest forms of animation, completely using human sight as its method.

A Phenakistoscope featuring zebras and monkeys in a jungle setting, the zebras would run, and the monkeys would swing when viewed through a mirror. This particular phenakistoscope is from a competing product of the original production, “Mclean’s Optical Illusions or Magic Panorama” from 1833. This is a simplistic image, but phenakistoscopes became more complex as years went on. Source.

Like how the thaumatrope represents a flaw in human vision, the phenakistoscope fully represents the conditionality of vision. The human eye is susceptible to condition, to light, to distortion of light, to illusion. The illusion is only possible through a window, the mirror, showing the young the new concepts of the human eye as an unreliable “narrator” by itself. However, at the same time it shows it through an exciting illusion of movement. The Phenakistoscope saw mass popularity, being published under names like Fantoscope and “Magic Wheel”, leading to further visual toys being produced which would eventually overtake the simple phenakistoscope and thaumatrope. However, before we get into them let us take a quick sideroad into the world of photography.

A 1908 advertisement for a stereoscope viewer in the Pittsburgh Daily Post. It presents the stereoscope as a tool, and as entertainment. Source.

In 1838, Charles Wheatstone published a paper reporting an odd illusion he had discovered where two drawings of the same object, at slightly different perspectives, were placed next to each other the two would be fused together by the eye into a three-dimensional view of it. It is realized this is exactly how the eye functions, each eye taking its own perspective and the two images fusing together for a full three-dimensional view (Thompson). From Oliver Wendell Holme’s 1859 essay on the Stereoscope (After it gained mass popularity):

The two eyes see different pictures of the same thing, for the obvious reason that they look from points two or three inches apart. By means of these two different views of an object, the mind, as it were, feels round it and gets an idea of its solidity. We clasp an object with our eyes, as with our arms, or with our hands (Jacobi).

Wheatstone created a table-top device to demonstrate this effect more easily and clearly, thus the world’s first stereoscope was created, a product of the 19th century’s scientific endeavors.

However, the mass market version of the stereoscope would not be refined and produced until a decade later, by Davis Brewster (who you may remember as the inventor of the kaleidoscope and involved with the thaumatrope) who crafted it into a handheld model in 1849, enabling a scene to appear anywhere.

The refinement of the stereoscope just so happened to align with the release of the first photographs (the specific type called daguerreotypes) as well, enabling the device to show its true potential. “Once Brewster’s design hit the market, the stereoscope exploded in popularity” writes Clive Thompson of the Smithsonian, “The London Stereoscopic Company sold affordable devices; its photographers fanned out across Europe to snap stereoscopic images. In 1856, the firm offered 10,000 views in its catalog, and within six years they’d grown to one million.” The stereoscope, at least its phenomenon, is possibly one of the most long-lasting of these optical toys, considering 3D magic books are on the shelves that use stereoscope technology and some virtual reality headsets rely on the same visual illusion to function.

A stereograph of Indian people gathered outside of a building, created between 1860 and 1930. Stereographs were viewed as tools for exploring the world without literally traveling, however it also led to people objectifying different cultures as they were not people but depictions of people that lacked relation. Source.

The stereoscope equipped with the stereograph became a scientific tool, a toy, and an educational object. Astronomers used it to peer closer at celestial objects. “Astronomers realized that if they took two pictures of the moon—shot months apart from each other—then it would be like viewing the moon using a face that was the size of a city: “Availing ourselves of the giant eyes of science,” as one observer wrote. (The technique indeed revealed new lunar features)” (Thompson). It also became a tool of education, as a way for the child to view far off locations and immerse in a select scene, which the Victorian believed sharpened the child’s attention as their mind was “chaotic and unfocused”. The mass popularity of the stereoscope enabled mass collections of stereographs to develop, which further allowed people to see far off regions, of India, of Asia, of Africa, and the landmarks of Europe, South America, and their own America. However, overall, it remains a toy, a device for entertainment, a way to immerse oneself in another world, another plane, another region.

The stereoscope reflects the society’s interest in vision, the world, and the depths of the human eye. The lighting illusionary discovery reveals the eye to be more than seen, a thing to be further explored. The use of the stereograph reveals the human eye to have complex mechanisms of sight, what you see if not simplistic it is made up of two images. People collected hundreds of stereographs that depicted America, landmarks, animals, people, and any other thing you could imagine into countless to indulge in. However, it is important for the Victorian, and us, to remember however, a person inside of a photograph is not a person, it is the depiction of a person.

A 19th century advertisement for the Zoetrope from T.H. McAllister, describing the Zoetrope as “an instructive Scientific Toy, illustrating in an attractive manner the persistence of an image on the retina of the eye.” The nickname “Wheel of Life” comes from the way the images appear to “jump to life”. Source.

The direct improvement of the phenakistoscope was the cylindrical Zoetrope, first invented by William George Horner in 1834 (only a year or two after the phenakistoscope) who originally named it the Daedalum (the “Wheel of the Devil”) but only marketed in 1887 under the new name of Zoetrope (A combination of the Greek words for life and turn). It improves on the phenakistoscope in two aspects, the user did not need a mirror to observe the effect, and the device could be enjoyed by more than one person at a time. The Zoetrope works in a similar method, along with also being constructed of cardboard, to the phenakistoscope:

Photo included with the article, showing the construction of the zoetrope. Source.

The zoetrope is a mechanical device that produces the effect of motion through a rapid succession of static images, seen through the slits in a rotating cylinder. The sequenced drawings or photographs lie beneath the slits on the inner surface of the cylinder, and as the cylinder spins the viewer looks through the slits at the opposite side of the interior. This scanning action prevents the images from blurring together, and the viewer is treated to a repeating motion picture (Kumar).

The device is considered an early work of animation, along with the flipbook, and acts as a supplement to the evolving concept of human vision, deception, and illusion in the 19th century. From the time of its creation to its market appearance, P.T. Barnum rose to worldwide fame, the Civil war ended, the concept of photographs and spirit photography had arrived, and the societal concept of children had evolved. It is only just then, that the Zoetrope is succeeded by yet another evolution of vision, the Praxinoscope.

An advertisement for the Praxinoscope theatre at the 1878 Exposition Universal in Paris, highlighting its winning of a bronze medal. Source.

The Praxinoscope was created in 1877 by Emile Reynaud, a Frenchman. It is similar in design to the Zoetrope, however it has one innovation that makes it superior, it replaces the slits used to create the effect with narrow vertical mirrors placed in the center of the drum (Greenslade). This enabled even further wider audiences, along with cleaner, brighter animation which was vital in an era before the lightbulb. The praxinoscope garnered massive popularity, being used in homes, and presented as theatres like the one above.

The zoetrope and the praxinoscope both represent the later ends of the 19th century in terms of the view of vision, as this concept that exists to be explored, a thing that can view through windows into other realities, that of film, of moving pictures, of the modern cinema experience. They stand as foundational objects to the modern film industry, with film coming quickly after their creation in the late 1800s and early 1900s. While these toys are simplistic to the modern viewer, they stand as important milestones of concepts of human vision, of looking askance, and of the eye.

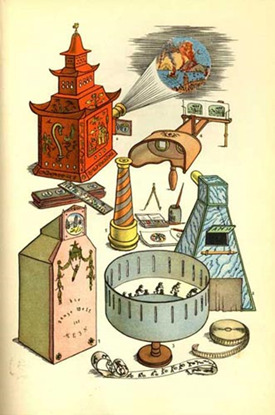

Lithograph by Alfred Mahlau from “Spielzeug, eine Bunte Fibel”, a german book from 1938 by Hans-Friedrich von Geist. The lithograph shows a Kaleidoscope, A Stereoscope, a Zoetrope, along with later film mediums. Source.

The 19th century was an era of vision, the exploration of it, the evolution of it, and the play of it. Within the century we see the concepts of vision evolve, from the simple exploration of tricks of the eye to the questioning of the credibility of it, alongside it we see these optical toys appearing as exploration of the concepts. The kaleidoscope appears in the early 19th century as an exploration of the interaction of the eye and light. The thaumatrope flips as a exploration of an illusionary sticking image of the eye. The phenakistoscope spins to look at how the interaction of the eye and light can create illusions of movement. The stereoscope appears as another exploration of an illusion the eye creates, being used to explore other regions and concepts. Finally, the Zoetrope and the Praxinoscope make their way in, becoming early concepts of animation by building off the concepts of the phenakistoscope, and enhancing the effect with more slits and mirrors.

While these toys may seem laughably simplistic to us, there is a reason things like yoyos, balls, and dolls are still so amazingly popular along with these very optical toys being recreated and sold. There is a joy in simplicity, there is joy exploring the human eye.

Farman, Jason. “The Forgotten Kaleidoscope Craze in Victorian England”. Atlas Obscura, November 9th, 2015. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-forgotten-kaleidoscope-craze-in-victorian-england

Greenslade, Thomas B. “Praxinoscopes”. Instruments for Natural Philosophy, Keyton College. http://physics.kenyon.edu/EarlyApparatus/Optical_Recreations/Praxinoscopes/Praxinoscopes.html

Gunning, Tom. “Hand and Eye: Excavating a New Technology of the Image in the Victorian Era” Victorian Studies, Vol. 54, No. 3, Indiana University Press, Spring 2012. Pgs. 499-501, 513.

Herbert, Stephen. “The Thaumatrope Revisited; or: "a round about way to turn'm green". The Wheel of Life, https://www.stephenherbert.co.uk/thaumatropeTEXT1.htm

Jacob, Carol. “Tate Painting and the Art of Stereoscopic Photography”. ‘Poor man’s picture gallery’: Victorian Art and Stereoscopic”. Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/display/bp-spotlight-poor-mans-picture-gallery-victorian-art-and-stereoscopic/essay

Kamar, Julie. “The Wheel Of The Devil - The History Of The Zoetrope From Ancient China To Pixar”. June 1st, 2012. Thalo, https://www.thalo.com/articles/view/343/the_wheel_of_the_devil_the_history_of_the

Thompson, Clive. “Stereographs Were the Original Virtual Reality”. Smithsonian Magazine, October 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/sterographs-original-virtual-reality-180964771/

“A Short History of the Phenakistoscope” June 28, 2014. Juxtapoz: Art & Culture, https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/news/short-history-of-the-phenakistoscope/

“Phenakistoscopes (1833)”. The Public Domain Review, https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/phenakistoscopes-1833

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Orangutan in the Room: 19th century and the Figure of Man

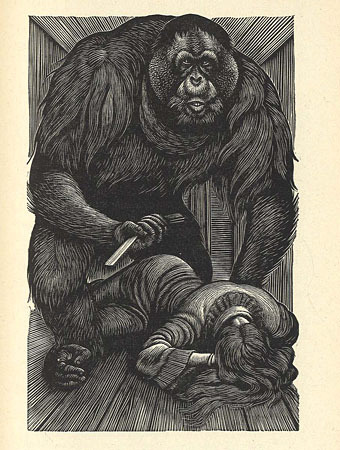

Fritz Eichenberg’s 1944 wood engraving illustration of Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. This engraving is interesting as it shows the animal as an actual Orangutan rather than a generic ape-monkey creature as previous depictions do. Source.

In 1839, Charles Darwin published The Voyage of the Beagle, the third account of his journeys on the ship the HMS Beagle with the prior two volumes already out. Later, in 1859, Darwin would publish The Origin of Species presenting his theory of Natural Selection and Evolution. Finally, in 1871 Darwin publishes The Descent of Man, and The Selection in Relation to Sex, where he lays out his concept of Sexual Selection, another form of biological adaptation related but not the same as natural selection. In all of these, Darwin proposed a singular idea that devastated, excited, and confused the public, that Humans and Apes had a relatively common ancestor.

This, along with several other scientific discoveries of the decade like photography and new astronomical concepts, created a vast public interest in science. Darwin specifically created an interest in the figure of ape in relation to the figure of man.

The figure of men in the 19th century itself was a sort of deception, constantly shifting and constantly changing in the new urban landscape. The faces of strangers would be countless, constantly morphing and shifting. Edgar Allen Poe would write about these fears in his short story, “The Man of the Crowd” where the narrator pursues a man who’s face shifts and morphs as he goes around town while Walt Whitman would publish “Faces” exploring Physiognomy, the pseudo-science of studying faces, with lines like:

“This now is too lamentable a face for a man

Some abject louse asking leave to be, cringing

for it,

Some milk-nosed maggot blessing what lets it

wrig to its hole.

This face is a dog's snout sniffing for garbage;

Snakes nest in that mouth, I hear the sibilant

Threat” (302).

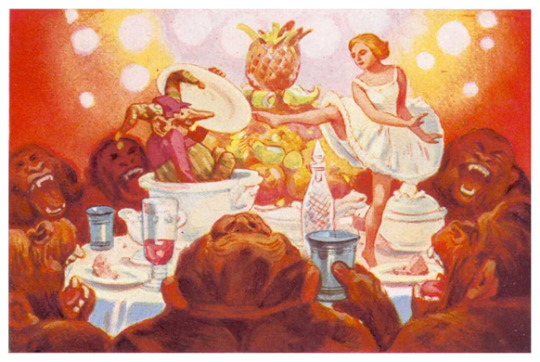

While this figure of man was a constantly shifting mass, the figure of the Ape however becomes this odd, solidified concept by the end of the 19th century. It is man but young, less intelligent but able to learn, capable of incredible violence but easily scared by violence upon him, child-like but immoral. Particularly, the Orangutan becomes this definite symbol of the Ape, shifting in appearance from the generic monkey to the genuine Orangutan form, displaying all the intelligence, horrific strength, and immorality the figure required. It becomes Man but not Man. The Orangutan is put under the name “Wild Man of the Woods”, an odd connection between ape and man. However, the figure of the Ape was not just applied to Apes and Monkeys.

The Native African (and African Americans) are continuously tangled in these narratives of apes and monkeys, being compared to them, related to them, and placed side by side to them in an equality. The 19th century viewer saw Africa as a barbaric, primitive country, full of ignorant, child-like, immoral souls who were in desperate need of Christianity. When explorers, more so invaders, brought relics of this foreign country, particularly animals like birds, fish, and, yes, Orangutans, the figure of the Ape became this outline of Africa.

The figure of the Ape becomes an allegory for the figure of Man itself, through the dehumanization of the natives of Africa and the discussion of what constitutes “Human” intelligence. Orangutans, spelled Orang Outang, become a figure of the exotic to the 19th century viewer, representing all the brutality, mock intelligence, and childlike tendencies they perceived Africa and Native Africans to possess.

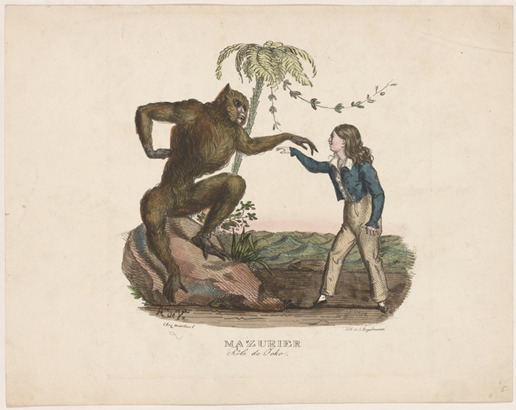

From 1826, An illustration of a scene from Jocko, specifically the play based on the Book, about an Orangutan who lives on a Portuguese Trader’s plantation as a servant and pupil. He lives in his own “jungle hut” and spends his time teasing slaves and workers on the plantation. In the plot he saves the traders son but is shot due to belief he is hurting him. He lives long enough to retrieve hidden diamonds from his hut for his master. The book and play represent a significant connection between Man and Ape, along with this odd relation between the plantation slaves and this creature in a hierarchy. Source.

In the early 19th century, the figure of the Orangutan appears in the theatrical sphere, “Man-Monkey” roles in European and Southern American Theatres (which eventually made its way to America), which saw people dressing up as apes and doing various acts of athleticism. It was a way for the early viewer to consider the relation of man and ape, “nineteenth-century popular theater had found the vehicle—the “man-monkey” role—through which to engage with growing public interest in the nature and origins of humankind” (Cribb, Gilbert, and Tiffin, 156).

The figure of the Orangutan in the theater had little specifics, “this form of theater cared little for specificity when it came to representing orangutans or other primates, and even less for realistic plots”, the figure of the ape was shifting, never a singular creature. The Ape was not yet alluded to humanity fully, more animal. “The most successful works in this genre excited audiences with the frisson of species similarity through skillfully executed performances, even if their plots were generally unequivocal about where the lines between humans and animals should be drawn” (157). Darwin’s publications only pushed interest in this role further, letting it remain popular until the end of the 19th century where trained Orangutan acts carried on the spectacle of the Human Ape connection.

The “Ape” was always the foreign element, in some scenarios it would be a servant, usually in an “exotic” location, such as one from an 1806 play that depicted one “ fighting valorously alongside him against ferocious “savages”. Others would be “devious and lustful” creatures, In one play called Monkey Island, or, Harlequin Island and the Loadstone Rock from 1824 the plot revolves around a man and a woman trapped on a foreign island, “run by scheming monkeys and baboons that dress and behave like humans. Their ruler, an “ourang outang,” captures the woman and attempts to rape her, but she escapes” (158).

“Am I A Man and A Brother” from 1861, titled “Monkeyana”, alluding to both contemporary debates about evolution and slavery and the connection between Man and Ape, but more specifically relating the African to Ape. “Monkeyana” is taken from 24 etchings by Thomas Landseer in 1827, a series of satirical cartoons depicting monkeys in human scenarios. In the western tradition, Monkeys embodied sinful qualities. Source.

The Orangutan fell into two narratives, the “Good” Ape” to parade as the good servant or “savage”” as they had become allegorical to in plays set in “The New World”, and the vehicle for debate of species (161). The Orangutan as a figure was used to “probe human fears and foibles in topical narratives” (173). They became this figure through which to explore Africa, a costume for the viewer to easily slip into or for the natives to be forced to wear.

As the concept of the “Man-Monkey” role developed however, it grew increasingly racial (perhaps just more racial) in various ways. The Ape character would be presented against “Savages”, such as Indians or Africans. They would presented as “Good Savages” like in the 1840 play Bibboo, or the Shipwreck and The Ourang Outang, or the Indian Maid and the Shipwrecked Mariner, where “the orangutan proves himself more faithful than the beautiful and alluring “nut-brown” Indian girl who, Pocahontas-like, defies her tribe to aid the interlopers” (162). In a different instance, African cultures are directly tied to “Apes” such as “one occasion, man-monkey actor Harvey Teasdale deliberately leaped (in full monkey suit) into a group of “Bosjesmans” (a different term for one of the foraging ethnic groups from Southwest Africa) who had been brought to Liverpool to perform their customs” (163). Later, in 1847, Monkey of the Plantation directly likened the “Bosjesmans” to “orangutans and other primates”. This is a only few instances, amongst numerous ones that have been lost to time.

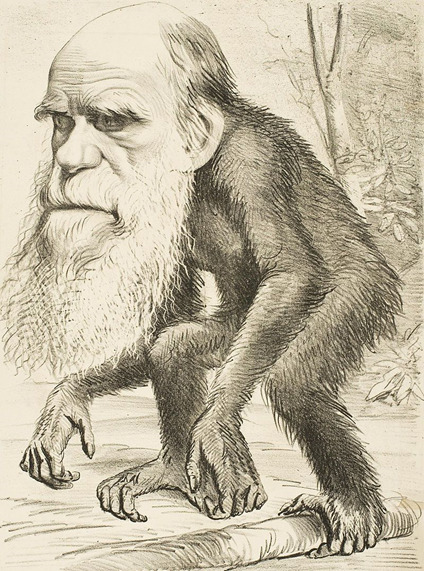

Charles Darwin depicted as a Chimpanzee from 1871. It was published in newspapers as a mocking of the evolutionary theory, as the culture at the time was heavily religious and saw the relation of Man and Ape as insulting. Source.

The role of and perception of Ape in theatre, specifically Antebellum theatre which consisted a large of Minstrelsy and the mocking of the African American figure, evolved as the 19th century went on. Particularly, the publication of Darwin’s theories saw a change in the figure of the Ape, shifting into these discussions of relation of Man and Ape and being twisted into racial allegories between “Savages” and slaves and if they constitute as human.

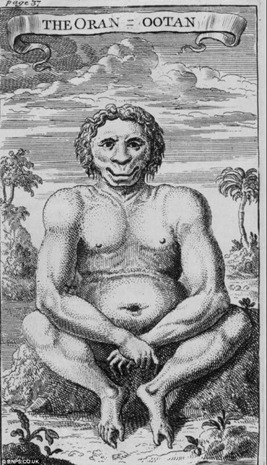

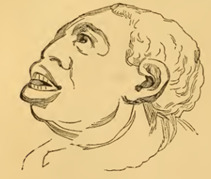

A depiction of Vesperitlo homo presented as less specifically Orangutan and more vaguely simian from 1835. On the right is a depiction of the Bipedal beavers, which ironically appear to be more advanced in development but ignored for the creatures with a distinct human-esc form. Source.

The figure of the Orangutan, at least the face, first appeared in specifically American popular culture in 1835 with the one of the first newspaper-originating fake news, the Moon Hoax, where a series of articles were published in The Sun falsely attributed to John Herschel (they had been made by the editor Richard Locke Adams), one of the most popular astronomers of the time, that reported that life had been seen on the moon. The reports laid out a world of booming foliage, mountainous regions of vermilion, single-horned blue deer, bipedal beavers with huts, and humanoids covered in “short and glossy copper-colored hair” with head hair that was “darker color than that of the body, closely curled, but apparently not wooly” with a face like a “large orang outang” (Locke 15).

The world of the moon in these reports sits as an odd allegory to Africa, this amazingly foreign world with beings that are, as Kevin Young puts it, “stereotypically black” and are close to “a range of racial types” and are bereft of Christianity, and thus, “civilized” society. Two varieties of Vesperitlo homo, the scientific name subscribed to these creatures, exist in this world with the dark skinned variety being immediately criticized and placed hierarchical lower than the lighter skinned variety, simply because the former is observed in mating while the latter is observed in religious and community actions. It reflects the view of the native African the European and American colonizer had, as these brutal, savage people in need of Christian-orientated salvation from basic human interaction.

Additionally, during this same time the Moon Hoax, African Americans were being presented in sideshows in the same caliber as, you guessed it, Orangutans. “Peale’s Muesum, across from City Hall, was now featuring a “living ourang outang, or wild man of the woods” named Joe; the creature had been wrenched from his mothers breast” though just streets away upstairs of Niblo’s was “Joice Heth…born a slave in Virginia…claimed to have been George Washington’s nursemaid” (Goodman). This narrative of being torn from family is oddly found in both narratives of apes and slaves. P.T. Barnum created a fictional account for Joice Heth he used in the Northern states (which were majorly abolitionist), claiming she was entertaining to save her great-grandchildren from a slave owner, who was written as being “highly respectable” and willing to set them free for “one-third of what they cost him” (Barnum 107). This narrative of being torn from family is found in both slave owners and abolitionist narratives alongside “exotic” animal capturers and advocates. It is this human feeling, this link of man and ape, of the ape and the slave for the 19th century viewer.

A depiction of the Orangutan from Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue from 1931 by Harry Clarke. The Orangutan is depicted as this grotesque elongated humanoid form, corpses of its victims gruesomely thrown around the room. Source.

Edgar Allen Poe published two stories involving Orangutans revolving around them as an allusion to man and the “exotic”, The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1842 and Hop Frog in 1849.

The Murders in the Rue Morgue is Poe’s and the world’s introduction to the detective genre (being one of the earliest detective fiction story), bringing forth this character of C. Auguste Dupin, an isolated American scholar with a remarkable eye for the non-obvious truth. The scenario Poe puts forth is a classical locked room mystery, two women are murdered on the top floor of a building in the middle of the night, with no obvious way out as the trapdoor leading to the roof is nailed down and the windows appear held down. Forgive me for ruining the ending, if the prior photos did not, but the murderer is an Orangutan, who climbs up a weather pole, through a window with a broken nail, and accidentally murders the women with a razor in an attempt to mock shaving before escaping into the night.

The Orangutan is represented as Child-like, it only kills because it is attempting to copy it’s owner shaving, it only hides a body out of fear of being punished, it only runs to explore. Yet at the same time it is put through an anthropocentric lens, looked at under human morals and behavior (Granted Orangutans are believed to be the closest Ape to humans intelligence wise). In the discussion of Apes and their relation to Man, Poe describes the Orangutans actions as “a grotesquerie in horror absolutely alien from humanity” (Poe 133). The Orangutan’s backstory finds itself uncomfortably close to how slaves are brought over, though simply put they were treated the same way as the foreigner was seen as less than human, landing in Borneo where it is captured and brought to the Americas with “great trouble, occasioned by the intractable ferocity of his captive” (137). The Orangutan becomes this easy allusion to the foreign, through the treatment the African people saw.

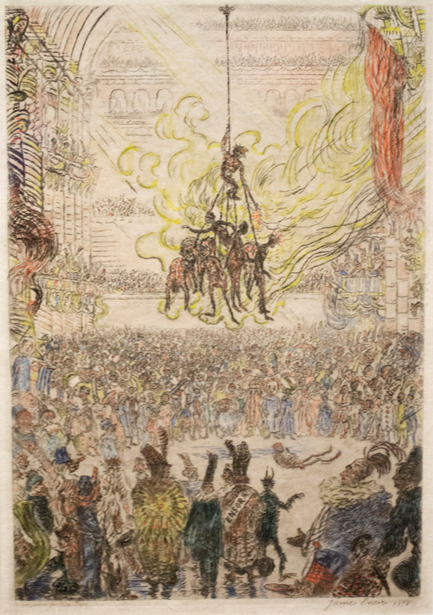

“Hop Frog’s Revenge” by James Ensor, 1898. This illustration depicts the horrific end in all its glory, the crowd of shocked people, the grotesque collection of blackened, burning bodies, with Hop Frog scampering up the chain to his escape. It is interesting the depiction of Hop Frog across most illustrations is this odd, thin, nymph like figure that contrasts his description. Source.

Hop-Frog shows a far very different, and more complex, depiction of the Orangutan, in two specific forms. It is the classic Poe horror story, short, bitter, and distressing. The title character Hop-Frog is a “fool” kept around for his ability to humor others, while also existing as a spectacle as he is called both a Dwarf and a cripple. “Without both a jester to laugh with, and a dwarf to laugh at” says Poe for the reason the monarch keeps Hop-Frog around (441). The plot centers around the king, cruelly forcing Hop-Frog to drink wine against his will as the king laughs at him, then proceeding to kick Hop-Frogs only friend, Tripetta, when she attempts to help him. Hop-Frog, in revenge for the kings cruelty, formulates a plan during the masquerade ball, convincing the King and his Advisors to dress up as Orangutans “the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs” (444), drenched in tar and covered in flax, running into the ball in a jest to scare the guests. Hop-Frog then proceeds to tie up the “Orangutans” with chain (as agreed as part of the jest) but rises them in the air and lights the group of tar-drenched, flax-covered men on fire to the horror of the party guests. Hop-Frog escapes with Trippeta into the night, while the people of the Kingdom watch their king burn into a “fetid, blackened, hideous, and indistinguishable mass” (447).

It is this horrific story of revenge, some argue too much revenge, that depicts Orangutans as both the victim of their own actions and the perpetrator of those actions. I stated earlier that there is two forms of depiction of the Orangutan in this story, one is the “Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs”, the other is Hop-Frog himself.

Hop-Frog and Number One by Stefan Mart in Tales of The Nations from 1933. It depicts Hop-Frog laying out the “Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs” plan to the king and his advisors. This is yet another depiction of Hop-Frog as imp like. Source.

Hop-Frog is never stated flat out called an Orangutan; however, his description is aptly describing one. He is described as “a dwarf and a cripple” due to his “inability to walk as other men do. In fact, Hop-Frog could only get along by a sort of interjectional gait- something between a leap and a wriggle, a movement that afforded illimitable amusement” (441-442). Along with this, he is described as having:

“prodigious muscular power which nature seemed to have bestowed upon his arms, by way of compensation for deficiency in the lower limbs, enabled him to perform many feats of wonderful dexterity, where trees or ropes were in question, or anything else to climb. At such exercises he certainly much more resembled a squirrel, or a small monkey, than a frog” (442)

His dexterity in climbing is further compared to a monkey’s, “to the centre of the room- leaped, with the agility of a monkey, upon the kings head- and thence clambered a few feet up the chain” (446).

Before Hop-Frog burns the king and his advisors, his teeth are revealed in his rage, “fang-like teeth” which had been repeatedly making a grating sound heard throughout the story, “who ground them and gnashed them as he foamed at the mouth” (446). The grating sound is heard immediately after the King forces him to drink, when he kicks Tripetta, and finally when Hop-Frogs revenge is done.

Furthermore, Hop-Frog is represented as being from “some barbarous region” and “had been forcibly carried off from their respective homes in adjoining provinces, and sent as presents to the king, by one of his ever victorious generals” (442). Tripetta and Hop-Frog arrived together, both representing parts of this “barbarous region”, Tripetta, the exotic beauty who “universally admired and petted”, and Hop-Frog, the barbaric African depicted literally as an animal or as close to one as you can get.

“The Eight Chained Orangutans” thus represents the ultimate revenge for Hop-Frog, to literally turn the king and his advisors into what you are (or what they see you as) and destroy them in front of the kingdom your forced to be a spectacle for. It is literally turning the spectator into the spectacle, a burning mass of blackened bodies. It is the Ape turning human, the human turned Ape, and the King into the Fool.

“Tripetta Dances”, another illustration of Hop-Frog by Stefan Mart. It depicts the king and his Advisors as Orangutans, laughing at Hop-Frog and Tripetta as she dances. Source.

Both stories created with an Orangutan featured in them in drastically different circumstances. The Murders in the Rue Morgue depicts the Orangutan, and thus all that this figure of the Ape alludes to, as Child-like but dangerous, intelligent to a degree but not enough to be “human”, it is a being that represents the barest echo of the African, a loose connection by shared treatment. On the other hand, Hop-Frog presents the Orangutan as this symbol of the foreign, that is ridiculed and mocked for existing as it looks, that seeks its revenge for actions done against it. It takes an eye for an eye, rather than mocking an action for an action. It’s a development in Intelligence (along with the fact Hop-Frog speaks) towards the viewer. In Hop-Frog, as a character, this leads to horrific consequences, and for the King and his councilors it speaks death for their cruelty upon the foreign, the African.

It is an odd coincidence then that this story that links Ape and Man through action and morality, is published the same year as the theory that linked Man and Ape in evolution.

An early 1860s advertisement for “What is It?”. The text below it reads “Is it a lower order of man? Or is it a higher development of the monkey? Or Is it both in combination? Nothing of the kind HAS EVER BEEN SEEN BEFORE! IT IS ALIVE!” It indulges in these thoughts of hierarchy, the thought that there is “low orders” of man and Africa is where they would be. Source.

After 1859, the comparison of Ape to Man exploded in the popular culture, leading to more comparisons and more racist allusion. Only three months after Charles Darwin’s publication of Origin of Species, P.T. Barnum introduced in 1860 what he called a “missing link” between man and ape in the figure of “What is It?”. The name came from Barnum presenting the actor to Dickens, who replied “What Is It?” It played on peoples hierarchical thoughts, racist concepts, and view of Africa along with the growing public interest in this concept of Man being linked to Ape.

To look beyond the image of the Half-Man, Half-Monkey, as P.T. Barnum presented him, we see a black African American performer named William Henry Johnson being described as having “the head like the slim end of an egg, a long broad nose and a prognathous jaw” (Zip The “What Is It?”). However, to the public he becomes not man, but not ape, but “MAN-MONKEY!, a most singular animal, which, thought it has many of the features of characteristics of both the human and brute, is not, apparently, either, but, in appearance, a mixture of both- the connecting link between humanity and the brute creation” (Barnum 134). P.T. Barnum positions “What is It?” as neither man nor what he calls “Brute”, implying ape but the same language is used to describe Native Africans in this period, this link or mixture of the two, neither the figure of Man or the figure of Ape. This depiction as the African as the inbetween of Man and Ape became this popular cultural touchstone, being used in arguments against slavery, and specifically as part of Anti-Lincoln arguments.

“What Is It?” is depicted as this feral, animistic proto-human, indulging in these hierarchical thoughts of Africans as lower, less developed, and thus less “human” yet a “wonderful freak of Nature” ( Barnum 134). Barnum details this narrative of him being captured, all the while directly linking him to apes. “They were in a perfectly nude state, roving about among the trees and branches, in the manner common to the Monkey and Orang Outang” and draws notice to his head which “combines both that of the native African and of the Orang Outang”, he goes on to compare the arms and legs of “What is It” “like those of the “Orang Outang”.

Additionally, Much like the Orangutan of Poe’s early detective story, “What is It?” is presented as child-like at “humanity”, Barnum advertises “The walk of What Is It is very awkward, like that of a child beginning to acquire that accomplishment.” He presents this “link” of Man and Ape, presents it as a mixture of Native African and “Ourang Outang” placing it (and native Africans) underneath the 19th century average middle-class white audience member in the hierarchical mind. “What is It?” presents a fake “direct link” between African and Ape, indulging in racist concepts of Africa and the newfound interest in the connection. It echoes the early 19th century theatrics, with the Man-Monkey, a spectacle of Ape and Man connection.

An illustration of an “Oran Ootan” from 1718’s first edition of Daniel Beeckmans’s A Voyage to and from the Island of Borneo. The Orangutan is depicted entirely humanlike, being shown to grow hair only “where it grows on human bodies” as Daniel says. Source.

For the 19th century viewer, the figure of the Ape, particularly the Orangutan, becomes this symbol of the foreign world. In theatrics Apes are presented against “savages” in equalitys, while at the same time being compared to Man through the fact they are played by men in costume. The Moon Hoax of 1835 echoes and mirrors the views the 19th century person had of Africa as this alien, wondrous world that is in need to colonization, making these bat people that are ranked based on skin tone. The stories of Poe involving Orangutans offer these narratives about the figure of the African in relation to the acts of the White Man, be that those actions will be repeated in mimicry or that those actions will eventually be turned on you in revenge. Finally, “What Is It?” represents this attempt to link the figure of the Man and the Ape, through this racist, hierarchical lens preying on the scientific hungry 19th century American.

As these questions of what “humanity” constitutes went on, African Americans and Native Africans found themselves tangled up in these discussions as people dehumanized them to be “less than human”, becoming Ape. Through Narratives of the Ape, we can see how people see those they consider “less than human”, be that this colorful figure of the Orangutan sidekick, or the mystical Bat People in need of teaching, or this jester who takes bitter revenge. It is human to consider what human is, it is less human to say, “What Is It?”

Cribb, Robert, Helen Gilbert, Helen Tiffin. “Wild Man from Borneo: A Cultural History of the Orangutan”. University of Hawai’I Press, 2014.

Edgar Allan Poe. “Edgar Allan Poe: Complete Tales & Poems”. Introduction by Wilbur S. Scott, Castle Books, 1985, Pgs. 133, 137, 441-442, 444, 446.

Goodman, Matthew. “The Sun and the Moon: The Remarkable True Account of Hoaxers, Showmen, Dueling journalists, and Lunar Man-Bats in Nineteenth-Century New York”. Perseus Books Group, 2008. Pgs. 8-9.

Locke, Richard Adams. “Great Astronomical Discoveries Lately Made By Sir John Herschel”. The Sun, August 25th, 1835, Pgs. 15-16.

Phineas T. Barnum. “The Colossal P.T. Barnum Reader: Nothing Else Like It In the Universe.” Edited by James W. Cook, 2005, pgs. 134-135.

Young, Kevin. “Moon Shot: Race, a Hoax, and the Birth of Fake News”. The New Yorker, October 21, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/moon-shot-race-a-hoax-and-the-birth-of-fake-news

Zip the “What Is It?”. Issues 48 & 49, Weird N.J., 2017. https://weirdnj.com/stories/local-heroes-and-villains/zip-the-what-is-it/

0 notes

Text

A Spectrum of Scares: The Red Scare, the Lavender Scare, and mid-20th century paranoia

History isn't something you look back at and say it was inevitable, it happens because people make decisions that are sometimes very impulsive and of the moment, but those moments are cumulative realities.

- Marsha P. Johnson, A Black Transgender Drag Queen

“A Promotion We Can Do Without” from the Miami Herald, 1954. It accompanies an article about police being “soft” on “perverts” (the typical term for a homosexual in this period) in Miami leading to moral failure. The first line of the paragraph in the top left reads, “Sex perversion is a growing public problem”. Source.

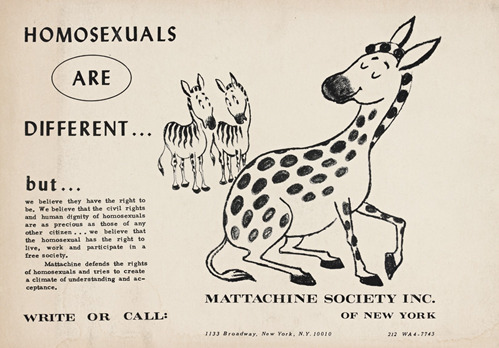

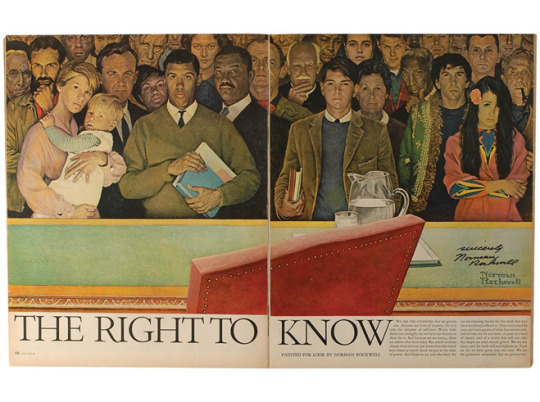

The history of the LGBT+ community in America is a textbook of struggle, just as Marx claims history to be patterns of class struggle. The lesbian is told she needs a man, the homosexual is blamed for moral failure, the bisexual is called confused, and the transgender called mentally ill. They are constantly alleged to be corruptors, perverts, and conspirators trying to undermine the “normal” straight society, in other wards they are the “other”. In the McCarthy era, we were alleged to be Communists; but then again, who wasn’t?

The year is around 1948, the second World War had only ended 3 years ago, and America is feeling powerful. They’ve come out the victor with their allies and defeated the Nazi Party. However, their society is now forever tinged with this xenophobic culture, powered by anti-German, Russian, and Japanese propaganda, that paints them broadly as, President Donald J. Trump tweeted barely a week ago, the “Red Wave”. As Communist government expands in Eastern Europe, the communist, to the American, becomes a boogeyman, a coverall for any ill moral, counterculture, or otherwise “bad” action that anybody does. Furthermore, the Cold War pushes this even further as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union boil to a tipping point awakening anti-communist hysteria from the 1930s. Simply put, The Soviet Union and the US were goading each other constantly. Thus, begins McCarthyism and the second Red Scare (the first being in the late 1910s during World War 1).

The communist, the so called “Red Menace” becomes the anti-capitalist, the socialist, the critic, the questioner, the democrat, the minority, and, most important to us, the homosexual.

Amidst the McCarthy investigations and hearings, the societal panic, and the illusionary massive plan of the communists to uproot American Society (though we were literally pointing nuclear missiles at eachother), the second Red Scare was used to discriminate further against the “other”. All areas of minority were targeted for being Communist, some directly by McCarthy, from Black Americans, to the non-Christian, to the LGBT community. The figure of the Communist and the “other” became one in the same.

A newspaper headline from 1961 stating the “Reds” blackmail Homosexuals into being Communist spies. The paragraph above it reads, “The F.B.I. knew those two code experts were fruity fellows but nothing was done about it until the boys has already minced off to Moscow.” Their homosexuality is summarized as “perverted pursuits in hotel rooms”. Source

This resulted in the Lavender Scare, a mass investigation and eviction of LGBT, primarily gay people, from United States Government due to fear of them being Communist infiltrators along with public beliefs of the gay person. McCarthy himself declared the “homosexual” to be a threat to the American lifestyle, as he thought they could be easily blackmailed by the communist into revealing state secrets or be “Corrosive” to their coworkers moralities. The Lavender Scare is the people’s moral fears over the homosexual lifestyle colliding with Mycarterism-era conspiracy fueled paranoia.

A 1950s Newspaper article warning Americans “DON’T Patronize Reds” in the entertainment industry. The last line reads, “every time you permit REDS to come into your Living Room VIA YOUR TV SET you are helping MOSCOW and the INTERNATIONLISTS to destroy America!!!” Source.

During the late 1940s and stretching into the late 1950s, a “Red Scare” occurs, a conspiracy theory where the American people believed that Communists had infiltrated their society with the goal to bring down democracy. People believed “Reds” had infiltrated government, Hollywood, TV, schools, and any other public place with an express hope of “corrupting” the populace. The era overall is called the “McCarthy Era” after Senator Joseph McCarthy, a right-wing republican who in 1950 rose to prominence by declaring there was “Communist penetration of the State Department, the White House, the Treasury, and even the US Army” (Miller Center). In his speech, titled “Enemies Within” he declares:

The great difference between our western Christian world and the atheistic Communist world is not political, gentlemen, it is moral. For instance, the Marxian idea of confiscating the land and factories and running the entire economy as a single enterprise is momentous. Likewise, Lenin’s invention of the one-party police state as a way to make Marx’s idea work is hardly less momentous…Karl Marx, for example, expelled people from his Communist Party for mentioning such things as love, justice, humanity or morality. He called this “soulful ravings” and “sloppy sentimentality”

He points the finger at the end, claiming:

I have here in my hand a list of 205 . . . a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department.

He later cut this list down to 57, in an address to President Truman, “Despite this State Department black-out, we have been able to compile a list of 57 Communists in the State Department”. Two of these cases specifically targeted homosexuals.

This speech polarized the nation, creating parties who both believed and dismissed his allegations. McCarthy in the early 1950s would comb over nearly all government departments, questioning countless witnesses (Who a large majority of the time were only accused of being Communist), and in 1954 it all cultivated in its peak, the McCarthy Hearings. The McCarthy Hearings were 36 straight days of televised investigative hearings ran by McCarthy, however this turned public opinion against McCarthy after seeing ludicrous claims by the Senator against trusted people, along with a well written criticism by Edward R. Murrow (Achter). However, the Communist fear would never truly fade, nor the effects this conspiracy theory created.

A McCarthy era flyer, urging the viewer to report any “suspected Communist Activity” to presumably the police or the House Committee on Unamerican Activities (HUAC) which were a committee entirely focused on monitoring Communist activity within the United States. Source.