Text

Provocation: Historical Poetics Now

This is the text of the “provocation” I delivered at the Historical Poetics Now conference at the University of Texas, Austin, this weekend. A forthcoming article in Literature Compass discusses Mary Austin’s theory of free verse and its effect on modernist conceptions of Native American poetry in more detail, as does my book manuscript in progress.

A Provocation from an Americanist

Thank you to the conference organizers for inviting me to be one of the provocateurs at this event––I’ll try to live up to the designation. I’ve been charged with being the provoking Americanist, and I’m afraid I’m also really a modernist these days, so I’ll be giving my views on what historical poetics offers from the standpoint of someone who works primarily with materials from the Americas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. My provocation today consists of two main linked claims: first, historical poetics is not only about historicizing poems, and second, historical poetics can help to elucidate some of the ways that contemporary literary studies remains attached to its white supremacist foundations. Put differently, historical poetics can be one tool we use to chip away at the foundational whiteness of literary studies.

Claim 1: historical poetics does not simply mean historicizing poems. A historical poetics approach to literary study pushes scholars to ask which terms we hold stable in order to narrate the literary histories that emerge in our scholarship. Work in historical poetics starts from the premise that, as Michael Warner puts it, the modern academic critic is “a historically unusual sort of person” (“Uncritical Reading” 36) whose habits of critical reading are markedly different from the habits of most other kinds of readers. Academic critical reading is very good at elucidating certain kinds of poetic texts, but many poetic texts have been illegibile to modern literary scholars––for instance, most of the poems written and circulated in the United States in the nineteenth century.

This situation meant that, for a few decades at least, nineteenth-century American poetry was essentially disappeared from English departments, aside from works by Whitman, Dickinson, and maybe sometimes Poe. As Kerry Larson writes in the introduction to the 2011 Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Poetry, “It cannot be said of nineteenth-century American poetry that it needs no introduction” (1). For generations of scholars, it seemed self-evident that convention, rhyme, repetition, and imitation were marks of bad poetry, and that bad poetry isn’t worth the investment of time required to make it yield interesting knowledge. Hence, nineteenth-century American poetry was simply ignored. Historical poetics scholarship, along with feminist recovery projects, book history studies, and any number of allied fields, has fundamentally reoriented our view of the nineteenth century in the Americas, pushing critics instead to see how twentieth-century literary critics “ask[ed] questions that nineteenth-century American poetry didn’t seem [able] to answer,” in the words of Mary Louise Kete (15). The scholarship that has investigated how to ask the questions that nineteenth-century American poetry does answer has been as varied in method and scope as nineteenth-century American poetry itself. In general, though, such scholarship can be said to push back against the once pervasive ideas that 1) readers have always understood capital P Poetry to be a meaningful generic category, 2) that conventionality is a mark of bad artistry, and 3) that poetic forms and genres evolved in any kind of progressive way. This latter strand of criticism is the strand I want to pick up in this talk today.

With the time I have remaining, I want to present to you a case study in historical poetics, to show what happens when we no longer hold generic and formal terms––especially terms like meter and prosody––stable as we analyze poetic texts. [I have to ask you indulgence here, because I’m going to be talking about modernist studies and texts from the early twentieth century, but it’s my hope that this conversation will have some theoretical utility for scholars working prior to the twentieth century.] As a practitioner of historical poetics, I am interested in the consequences of the return of nineteenth-century American poetry for fields that have relied on its disappearance for their own existence--namely, modernism. I am especially interested in the question of how to narrate historical accounts of modernist poetry from the premise that, as Max Cavitch so eloquently puts it, “Poetry’s liberation from the shackles of meter is one of the most important nonevents in late nineteenth-century literary history” (33). When scholars of modernism talk about free verse, they still position it as a real break with the prosodic experiments of the nineteenth century. This narrative covers over the white supremacist theories of meter that developed in the modernist era. A historical poetics approach to the history of free verse poetry can, I propose, reveal how white supremacist ideologies continue to inhere in some scholarly assumptions about the relative values of various poetic forms. In other words, historical poetics is not simply about historicizing poems; it is an approach that challenges the often reflexive, unexamined narratives of progressive generic and formal evolution that sometimes continue to structure otherwise historically-minded scholarship.

My abridged case study today is part of one chapter in the racialized development of free verse in the Americas in the early twentieth century. Mary Austin created a position for herself in the 1910s through the 1930s as one of the foremost “interpreters” of Native American poetry and cultural traditions. She was appointed to the School of American Research in Native American Literature in 1918, authored the “Aboriginal Literature” entry for the Cambridge History of American Literature in 1921, and published widely on Native American literatures and cultures in popular magazines like The Nation and Atlantic Monthly. She managed to attain this stature in spite of the fact that she spoke no Native languages. Though Austin did advocate for the importance of Native American poetry, which she presented as the earliest known form of free verse, she also managed to turn free verse into a tool of settler cultural domination. Austin proposed that free verse poetry was a technology for managing time—specifically, for integrating Native Americans into the relentlessly linear march of what Mark Rifkin has recently theorized as settler time. Austin’s theories of free verse had significant, distorting effects on the way Native American oral expressions were presented as poetry in modernist anthologies. While free verse is still all too often mapped onto historical narratives about progress and democratization, Austin’s work shows that ideas about free verse were in fact part of settler attempts to control and mediate Native cultural expressions in a way that benefitted non-Native artists and literary cultures. This case study highlights the need to question the way we narrate changes in the use and theorization of poetic forms.

I don’t have the space to get into all the wonderfully baroque and twisty logic behind Austin’s prosodic theories. I just want to highlight the effects of her understanding of free verse for Native poets. Austin argued that, because Native American poetry was a type of free verse, it had a unique relationship to the blank, white space of the printed page. She explained that printing what had been oral expression as free verse poetry revealed that, much like with Imagist poetry and other compressed forms, “the supreme art of the Amerind is displayed in the relating of the various elements to the central idea” (AR 56). Austin claimed that this economy of form showed that “the Amerind excels in the art of occupying space without filling it” (AR 56), both literally and literarily.

Furthermore, Austin argued, Native American poetry was “for the most part of the type called neolithic” (AR 20), and was incapable of being translated into the modern world without the resources of the English language. Austin’s logic went thusly: she argued that “accent does not appear to have any place in Amerind poetry” (AR 61). This mattered because accent in poetry was “a device for establishing temporal coincidences” (AR 63), both metrically within a poem and in a larger historical sense. Without the technology of accent, Native poetries were destined to remain firmly rooted in their “Neolithic” moment. By being translated into English-language poetic forms, however, that Neolithic verse could be brought into the future, and in the process the English-language interpretations of Native verbal arts would become privileged poetic objects. English free verse interpretations were needed to unpack the fossil poetry of Native verbal arts in order to preserve a cultural heritage that would otherwise have been lost in the inevitable march of historical and generic progress. Non-Natives (and only non-Natives) could create a “temporal coincidence” between the beginnings and the ends of poetry, according to Austin, through their use of accented poetic rhythms in “aboriginal” free verse forms. It had been the technology of poetic accent that had allowed Vachel Lindsay to create “points of simultaneity” between “the Mississippi and the Congo” (AR 32) in his free verse poetry, and it would be the technology of accent that would lead non-Native poets to nurture “the common root of aboriginal and modern Americanness” (AR 54) into what Austin called “the rise of a new verse form in America” (AR 9). The right poetic rhythms, in other words, wielded by white poets, could create material linkages between the past and the future, making history visualizable and graphically representable as the rhythms of modern poetry. Rhythm was a time machine that moved between the “unaccented dub dub, dub dub, dub dub, dub dub in the plazas of Zuñi and Oraibi” (AR 11) and the accented “chuff chuff of a steam engine” (AR 64). This translation across time would make those primal unaccented rhythms intelligible to the non-Natives on board the forward-moving train. Not coincidentally, Austin repeatedly returned to this image of a train as a sort of time machine running back and forth on a single track between the rhythms of “primitive” man and modern man, a la Back to the Future Part III. Running this track, according to Austin, allowed both rhythmic systems and both types of man to merge into a singular and inevitable creation—namely, the modern American.

Austin’s theories of Native American poetry as neolithic free verse affected the design of anthologies of Native American poetry in the modernist era. Take, for instance, the 1918 anthology The Path on the Rainbow, to which Austin contributed the introduction and seven “interpretations” of ethnographic translations of Native American songs.

The anthology was hugely commercially successful, and the form of the anthology was widely imitated well into the twentieth century. And that form is deeply influenced by the logic of generic and cultural succession. The anthology performs the metabolization of Native American oral arts by white poets in its very design. The anthology first presents literal translations of Native American songs and oral expressions, made by non-Native ethnographers and divided into “songs” from various geographical regions. Labeling these works as “songs” may seem to indicate an awareness that “poetry” and “verse” are non-Native categories, but the anthology works to fit these transcribed and translated oral expressions into a stadial theory of generic evolution, in which the earliest poetry was a communally authored oral expression that included ritual dance as a necessary component, and in which the end goal of generic evolution is individually authored printed poems. In the table of contents to The Path on the Rainbow, the translators of the collected “songs” are named, but they are not named in the text of the anthology itself, reinforcing the idea that the songs were anonymously or communally authored.

These ethnographic translations are followed by “Interpretations” by Constance Lindsay Skinner, Mary Austin, Frank Gordon, Alice Corbin Henderson, and Pauline Johnson. Where the ethnographic translations are marked by the names of their collectors and the tribal groups that produced them, the “interpretations” do not have consistent textual apparatuses to explain which sources, if any, the poets were interpreting, indicating that the cultural specificity of the oral arts of different Native groups mattered less to the anthology’s editors than the ways those oral cultural productions were interpreted by non-Native authors.

The message of this design is clear: as “neolithic” poetry, Native American verbal arts were waiting for more “advanced” literary artists to polish and perfect them. The anthology made Native American poetry “productive” for American literature. Its seemingly unsystematizable, unaccented poetic rhythms would be incorporated into the system of English-language poetic rhythm, meaning that Neolithic Native cultures would be brought into the modern world on settler terms. Austin’s introduction ends with a call to action for non-Native poets: the translators of Native American poetry had done their job, according to Austin, but “The interpreter’s work is all before him” (xxxii).

So, why have I yammered at you about problems in modernist studies for so long? I hope to have made a convincing case for the need to interrogate the terms that can easily go unquestioned in historicist work. One can historicize a poem without ever questioning why we call that text a poem; it is harder to historicize a poetic term or form or genre without questioning how ideological investments have shaped and continue to shape our literary histories. This, from my vantage point, is what historical poetics approaches offer to scholars working in any historical period. In the case study I’ve presented, I’ve tried to show that accepting one historically-situated understanding of a poetic form can perpetuate exclusionary, racist, colonialist lines of thought. To continue to narrate the advent of free verse as a break with the past, without acknowledging the white supremacist colonial thinking that helped to create that idea of a prosodic break, seems to me to be a pretty serious problem. It may be a problem specific to modernist studies, but I hope this talk can provoke discussion about the terms in other periods that tend to get stabilized or reified.

Works Cited

Austin, Mary. The American Rhythm. Harcourt Brace, 1923.

---. “Introduction.” The Path on the Rainbow, edited by George W. Cronyn, Boni and Liveright,

1918, pp. xv–xxxii.

Cavitch, Max. “Stephen Crane’s Refrain.” ESQ, vol. 54, no. 1, 2008, pp. 33–53.

Kete, Mary Louise. “The Reception of Nineteenth-Century American Poetry.” The Cambridge

Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Poetry, edited by Kerry Larson, Cambridge

University Press, 2011, pp. 15–35.

Larson, Kerry. “Introduction.” The Cambridge Companion to Nineteenth-Century American

Poetry, edited by Kerry Larson, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 1–14.

Warner, Michael. “Uncritical Reading.” Polemic: Critical or Uncritical, edited by Jane Gallop,

Routledge, 2004, pp. 13–38.

0 notes

Text

Quit Lit, Stay Lit, Light it All On Fire

I have fantasized often over the past three months about being able to make this announcement publicly: I’ve accepted a job as an assistant professor of English at Tulane (my second tenure track position; I’ve been at Missouri State University for three years). In addition to having fewer teaching duties and more support for my research, I’m getting an $18,000 raise (only possible because my salary has been criminally low, and it’s not even the worst of the worst!). I’m elated. But of course this is not an uncomplicated elation. This is also the time of year when a lot of brilliant people realize they can no longer sustain all the costs associated with looking for a good academic job (one with a salary that is at least not insulting and with benefits).

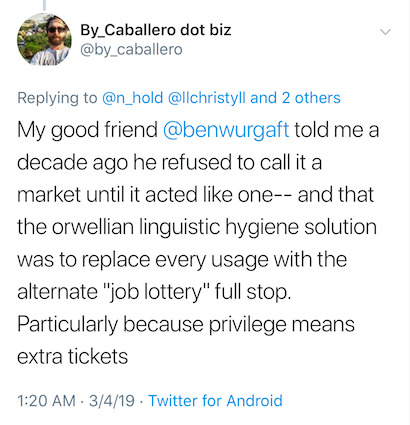

[I can’t co-sign this terminological change hard enough.]

This is a piece of stay lit, not quit lit. I’m in no position to tackle the complicated morass of emotion from which quit lit emerges (though I was in 2015, when my mentors convinced me to give it one more year). But I’ve been thinking a lot about the cost of a tenure track job, both literal and emotional. I’m offering what it has cost me because I think it’s good for everyone in academia—especially those who have been removed from the pain of job searching in this decade—to be reminded of what it takes to stay. I also want to think seriously about real (read: difficult and costly) solutions to a genuine crisis. (I’m not here for any of the “it’s always been bad” takes.) I don’t want to turn into the type of professor whose politics are performative. Nothing changes if the ones who stay don’t think seriously about the structures we’re staying in and propping up. (It’s also worth noting that not all tenure-track positions are created equal. I’ve been privileged to have the job I had at Missouri State. But I also worked my ass off, teaching between 60 and 90 students a semester, which, please never forget, includes a lot of time serving as a de facto counselor to students in crisis, a job for which I am most definitely not trained and which I find completely and utterly exhausting. Between all of that mental and emotional labor, service work, and trying to keep publishing things, most days I didn’t have the energy to follow the plot of a Top Chef episode, let alone organize for contingent faculty on my campus or anywhere else. And pre-tenure faculty are not exactly in the most secure positions when it comes to rocking the institutional boat.)

The cost of staying

Many people warned me before I started graduate school that I was “mortgaging my earning potential in my twenties.” I sort of understood this, but also I was twenty-three years old and had no real sense of what that meant. Eventually I’d have a stable job, so what did that really matter?

Well, for me now, at thirty-six, I see how it mattered. I’m not starving, but I have no savings (aside from $9,000 in a retirement account that I was only able to start at age thirty-three), no assets, and about $18,000 in debt (some low-interest student loans and some high-interest credit cards). Here’s how the credit card debt happened.

Income through grad school and first years on the job market:

2006–2007 (Grad School Year 1): $12,000 stipend plus $5,000 fellowship

2007–2008 (Year 2): $16,000 stipend plus $5,000 fellowship

2008–2009 (Year 3): $16,000 stipend

2009–2010 (Year 4): $18,000 stipend (raised because a TT faculty member went to bat for us—I think this was the year it was raised, though it may have been the following year)

2010–2011 (Year 5): $18,000 stipend

2011–2012 (Year 6): $18,000 humanities center fellowship at my home institution

2012–2013 (Year 7): $25,000 external fellowship

2013–2014: $19,000 salary at a one-year “VAP”

2014–2015: $38,000 one-year research fellowship

2015–2016: $26,000-ish adjuncting (4–6 courses per semester)

2016–2019: $52,000 salary in a TT position (3/3 teaching load)

2019–?: $70,000 salary in a TT position (2/2 teaching load)

Prior to the MSU job, 2014-2015 was the only year I made enough money to cover my expenses. My family is not in a position to help me out (my parents have had their own job struggles that have coincided with my college and grad school years). Each year there were things I had to have that I couldn’t pay for. They went on my credit card, which had a $20,000 limit, even though my annual salary was almost never above $18,000, because Bank of America is a predatory institution. I’ve never been able to successfully negotiate for more money or resources in a job offer because I’ve never had any leverage, because getting one job offer is a goddamned miracle.

In addition to the financial costs, there are also of course the mental and emotional costs of knowing you’re only going to stay in a place for a year (nine months, really), not to mention moving costs that may or may not be reimbursed, and the isolation that, for me at least, has come with the jobs I’ve had in very small, insular towns. Others have written about this more eloquently than I feel capable of. I just want to note that financial stress and emotional distress work together to amplify each other, as you know if you’ve ever had a depressive crying jag interrupted by a phone call from a bill collector.

I love this profession with my whole heart. It is a complete and total joy, even when it’s difficult, to think, write, and teach. It’s everything I’ve ever hoped for in a professional life. This shouldn’t be a privilege for the few. And that means the few need to fight harder for everyone else playing the good life lottery.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“We travel far in thought”

I'm not quite sure what this piece is: a travelogue, a defense of tastelessness, an exploration of the meaning and value of the sign "woman" now, a manifesto for living, a meandering record of thought. It's mostly a collection of things I needed to work out for myself that I post here in the hopes that they'll resonate with someone who's also trying to work some of them out.

I. Itinerant "My imagination wandered at will; my dreams were revealing.... Thoughts were things, to be collected, collated, analysed, shelved or resolved. Fragmentary ideas, apparently unrelated, were often found to be part of a special layer or stratum of thought and memory, therefore to belong together; these were sometimes skillfully pieced together like the exquisite Greek tear-jars and iridescent glass bowls and vases that gleamed in the dusk from the shelves of the cabinet that faced me where I stretched, propped up on the couch in the room in Berggasse 19, Wien IX." -- H.D., Tribute to Freud

I came to Vienna, like so many before me, for Freud.

In between conference presentations (one at the American Comparative Literature Association's conference in July in Utrecht and one at the Modernist Studies Association conference in August in Amsterdam), I am loosely tracing threads that made up the poet H.D.'s life a hundred years ago, including her time as an analysand of Freud in 1933 and 34. This has meant taking a meandering path from Amsterdam to Berlin to Prague to Vienna to Rome to Corfu to Athens to Syros to Lesvos to Zurich and back to Amsterdam over the past six weeks, planning each leg as I get to it, taking fast trains and slow ferries, writing and thinking all along the route.

There is no particular reason to follow these threads now. I teach H.D. occasionally, and I wrote an undergraduate thesis about her, but I don't work on her anymore (my conference presentations are about Mary Austin and James Weldon Johnson, contemporaries of H.D.'s who had nothing to do with her). But when I realized I was going to have a little over a month to travel in Europe, when I thought of where I wanted to go, I thought of Corfu, where H.D. had a vision that was significant for her, and that thought has shaped the contours of this trip.

It's fitting, given the Freudian connection, that as I've traveled I've discovered a number of submerged reasons for the sudden desire to return to H.D. now. They have to do with loss, and identity, and class, and criticism, and taste. They have to do with recovery, and with poesis. They're about solitude and connection. They're about the disconnect between my personal and my professional lives and the submerged threads that loosely bind them.

I started reading and writing about H.D. about the same time I started a relationship that lasted through almost all of my twenties. Though the relationship is long over, the process of sorting out the stories and the selves it generated hasn't really stopped for me. Is this an overdue project? Yes and no. Somewhere in A Lover's Discourse Barthes writes about those who are disorganized by mourning for longer than is acceptable. In Freud's terms, such a person is melancholic -- they can't get past an event or a feeling. I am prone to melancholic loops. It takes me ages to fully process emotions and to understand intellectually what I've been feeling intensely. Common knowledge has it that it takes half the lifespan of a relationship to get over it. If that's so, I'm well past the expiration date for thinking about this one in any kind of sustained way. But what does it mean to get over a part of your history, a part of the things that make you you? What would it mean to fully process it? What about the lingering emotions and questions that exceed the memory of the person or the relationship itself, which is really what I'm talking about here, since I no longer know the person(s) my ex has become, just as he no longer knows me? Isn't it worse to fail to reconcile with these lingering questions, to just put them aside, to pretend things end neatly, or at all?

Rebecca Solnit's A Field Guide to Getting Lost is one of the books I loaded on my Kindle before leaving the States (I know, I know -- a little on the nose for traipsing around Europe), and I was struck by the following lines in the essay "Two Arrowheads":

"A happy love is a single story, a disintegrating one is two or more competing, conflicting versions, and a disintegrated one lies at your feet like a shattered mirror, each shard reflecting a different story ... The stories don't fit back together, and it's the end of stories, those devices we carry like shells and shields and blinkers and occasionally maps and compasses."

One mirror shard: we made each other worse versions of ourselves. Another: I was cruel. Another: from the beginning, he had a lot of stories about who I was that didn't have anything to do with my experience of myself, that were classed and gendered on both sides.

I think that on some level, with this trip I'm trying to go back to a point before that doubled and multiplied story, to tell a new one of myself in relation to myself, my thoughts, my non-romantic relationships, places, books, systems, landscapes, genealogies. These are all stories I already tell myself, that I already share with others, that I already live, but I think I wanted to make them mappable. All of the international travel I've done in my adult life was with that partner; this is my first overseas trip alone. It is a chance to carve out new territory, layer new experiences on the old. It's a chance to, so to speak, reclaim my time, in a political era that is both hostile to my existence as a woman and that commits violence in the name of a quality it ascribes to my body (white womanhood, always in peril).

I wrote my undergraduate thesis about H.D. after falling in love with her epic poem Trilogy in a class on American women writers. At the time I knew it was pretentious to talk about this project as the beginning of my intellectual career, but I also really liked to talk about it in those terms. I had always been the smart kid, but this project was the first time that it truly seemed that ideas could be, not just instrumental (good grades, college admissions, stable career), not just interesting, but the stuff of a fulfilling life's work, a significant part of a life. The class in which I first read Trilogy was all about taking womens' ideas seriously. My undergraduate advisor took mine very seriously, encouraging me to apply for fellowships, nominating me for prizes, helping me to see my ideas as part of a conversation with "real" scholars -- the first of a long line of women to do so, to whom I owe the career I have now.

One of H.D.'s favorite tropes to play with was the palimpsest. "Palimpsest" refers to a piece of parchment or paper that has been written on, partially erased, and then overwritten with another text. The first writing is obscured and fragmentary, but still there as an echo or a trace. In extended, metaphorical usage, "palimpsest" is anything that has been reused, written over, but that still has some evidence of its earlier forms. It is the perfect image for a poet who wanted to think about history and the unconscious and trauma -- for all of the things that seem to be over and gone that keep returning in altered forms.

[Palimpsest in Ermoupolis]

The image of the palimpsest that H.D. worked and reworked is a way to think about loss differently-- to look at all the layers that make up a life, including the traces of things that have ended or been destroyed, that shift to form patterns and shift again to create a blur that maybe becomes a pattern again. I realized consciously, standing in front of the reconstructed Bella Venezia hotel in Corfu town (the original was destroyed, collateral damage of WWII), the site of H.D.'s Corfu event, that I came on this trip to think about my own personal palimpsest -- an image that's complicated and simple and meaningless and my entire world, the way that all individual lives are infinitessimally small and infinitely large at the same time. (At a Passover dinner in Missouri this spring, part of a new layer in my palimpsest, my friend Rachel read us the Talmudic saying that who saves a life saves the entire world. I think of this often when I'm tired of/from activist work in the Trump era.) My palimpsest includes that relationship that defined my twenties, but it does not start or end there, as I sometimes used to like to pretend it did.

Others have made the case for the seriousness of womens' thoughts and lives and creations in ways I now find more compelling, but H.D. will always be the first who made me think in a sustained way about these things. For that reason alone I wanted her to be part of the palimpsest or pattern or constellation I decided to trace this summer. I wanted to weave her more fully into the life that tendrils out from Iowa to Amsterdam to Corfu to Zurich to Missouri and on and on. And so I came to Vienna, and Corfu, and kept going.

II. Corfu: Vision "We had come together in order to substantiate something. I did not know what. There was something that was beating in my brain; I do not say my heart -- my brain. I wanted it to be let out." -- H.D., Tribute to Freud

I haven't thought about H.D. much since I started grad school. When you talk about H.D. in academic circles, you have to hedge and qualify. There is something embarrassing about her. She is excessive -- excessively melodramatic, excessively self-serious. And yet. And because. I like excessive women. I especially like women who insist on giving weight to the experiences and emotions that get coded as melodramatic or self-indulgent. I like H.D.

H.D. had a breakdown/breakthrough in Corfu town in 1920. She was fleeing London and WWI and what she experienced as the total fragmentation of her personal world and the world at large during the war. While staying at the Bella Venezia hotel, she had a vision of mysterious hieroglyphic writing on the wall of her hotel room. Much later, in 1933, she underwent a brief period of analysis with Freud in Vienna during which they tried to decipher what the writing meant.

[The new Bella Venezia]

I took great pleasure in re-reading H.D.'s account of her analysis with Freud on the train from Vienna to Rome, adding another layer on top of her narrative of their interweaved patterns, which linked Vienna and Rome and Corfu. I had forgotten how much I admire Tribute to Freud in all its excessiveness. It's self-indulgent, yes, and free-associative, yes, and at times utterly impossible, but it's also a text in which H.D. asserts her authority to interpret her own life in ways that Freud did not sanction, and in which she insists on a reparative reading of history, in spite of the very real trauma she lived through (H.D. experienced much of the violence of both world wars at firsthand -- she lost a brother in WWI, suffered a miscarriage, had a severely shell-shocked husband return home to her, and then lived in London during the Blitz).

In Tribute, H.D. repeatedly stakes a claim to her right to interpretation and to self-knowledge that both depends upon and is separate from Freud's authority. H.D.'s palimpsest involved stories and symbols from all kinds of classical mythological worlds, which overlapped with Freud's more skeptically tinged interest in antiquities and the history of religion. She explained that due to this overlap, "Sometimes, the Professor knew actually my terrain, sometimes it was implicit in a statue or a picture, like that old-fashioned steel engraving of the Temple at Karnak that hung above the couch. I had visited that particular temple, he had not" (10-11). It's a small but important moment in which H.D. asserts the value of her personal experience as part of her dialogue with Freud. He may be the analyst, he may have the collection to testify to a vast body of knowledge about the classical world, but she too had her ways of knowing.

[Part of Freud’s antiquities collection, which I spent a long time examining at Bergasse 19]

Famously (among H.D. scholars, at least), H.D. wrote that "there was an argument implicit in our very bones" (17), and that, though she "was a student, working under the direction of the greatest mind of this and of perhaps many succeeding generations ... the Professor was not always right" (24-25). Their argument came down, essentially, to hope; Freud diagnosed H.D. with a type of religious monomania -- the desire to found a new religion -- and saw her desire for meaningful signs and symbols, for a pattern or order in the world, to be a dangerous symptom of a delusion.

This was especially true when it came to what she called the "writing-on-the-wall" episode in Corfu.

[Writing on the wall 2017 -- the more things change. I’m writing this caption the day after Charlottesville.]

In her long description of the vision and her argument with Freud about the vision, H.D. explained,

"We can read my writing, the fact that there was writing, in two ways or in more than two ways. We can read or translate it as a suppressed desire for forbidden 'signs and wonders,' breaking bounds, a suppressed desire to 'found a new religion' which the Professor ferreted out ... Or this writing-on-the-wall is merely an extension of the artist's mind, a picture or an illustrated poem, taken out of the actual dream or day-dream content and project from within (though apparently from outside), really a high-powered idea, simply over-stressed, over-thought, you might say, an echo of an idea, a reflection of a reflection, a 'freak' thought that had got out of hand, gone too far, a 'dangerous symptom'" (75-76).

A hysterical woman, or an artist? Irrational emotions or ideas worth attending to? Her right to her ideas -- to stay with them, to think about them intently, to consider what they could signify aside from some kind of disorder in her mind -- is at the heart of Tribute to Freud as much as her genuine homage to the man who "had first opened the field to the study of this vast, unexplored region," the "shapes, lines, graphs [that made up] the hieroglyph of the unconscious" (140). It is this fight that remains at the heart of my love for her work.

III. Rome: Scale "What does it mean to call something petty, or to be petty yourself? Pettiness has to do with being out of scale. We might understand pettiness as a relation between attention and object of attention: you are being petty when a small or seemingly irrelevant detail generates disproportionate irritation; you are also being petty when irritation leads you to pay disproportionate attention to a small detail."

Though I didn't see it when it started (indeed, I didn't see it until after very many years of therapy and much nudging from my own analyst), the relationship that defined my twenties involved a lot of him telling me that my ways of being in the world were wrong -- something I had accepted in part because this was a recurring experience I had in college, at an institution that I at first romanticized and very quickly became horrified by, as I was trained out of old habits and systems and assumptions and socioeconomic expectations and behaviors (some amalgamation of lower middle class/middlebrow, always haunted by the specter of slipping back in the poverty of previous generations, never secure about money or status, not trained to like the "right" things or to behave in the right ways) into new ones (the cruelty of old money, the desperation of new or aspiring new money). I value some of this retraining when it comes to the scholastic realm, but a lot of it never really took. This failure to be retrained shapes the kind of thinker and critic and teacher I am now. It has a lot to do with why I live in Missouri and why I felt immediately connected to my community there even as I'm exasperated by it. It is part of why I'm writing this as a blog post and not as a piece of professionalized writing.

The only physical book I brought with me on this trip is the third volume of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels because I was right in the middle of it when my flight took off and because I couldn't bear to be apart from the story. (I'm dragging it around now even though I've finished it and don't have room for it in my backpack for the same reason. I almost tried to squeeze in a visit to Naples and Ischia but couldn't swing it, so Rome had to stand in.) These novels often get reduced to "those books about female friendship," which they are, but they are also about the details of what it means to be trained out of the class you were born into, and about what it means to think about womens' lives as part of larger movements and systems but also as outside of and irreducible to those systems. They're about what women lose, intentionally and not, under patriarchy and capitalism, how the game is rigged and how it forces you to play anyway.

Sarah Blackwood and Sarah Mesle are currently my favorite readers of these novels because of the ways they've thought about how criticism isn't really up to they challenges they pose. In "The Function of Pettiness at the Present Time," Blackwood and Mesle read Ferrante's novels as, paradoxically, importantly petty. It is the pettiness of the details of the womens' lives in the books, they argue, that manage to accurately capture "the grinding quality" of gendered experiences of "rape, loss, poverty, abuse, marriage, friendship." I write this in the days immediately following the clip of Maxine Waters reclaiming her time going viral, another perfect example of the huge importance of pettiness. Steve Mnuchin is of course the one actually being petty by refusing to answer Waters's question, but Waters is the one forced to repeatedly assert her right to not have her time wasted with bullshitting. She has to say it over and over and over and over and over. And she does because she is a goddamn heroine, but she still has to engage in the grindingness of the exchange.

A petty, huge fight I had with the first person I dated after the relationship that defined my twenties ended started with the words "what's so bad about sexism really, though?" I only wish that that person, bless his heart, could have realized how fully he was enacting sexist violence through that question and his continued insistence throughout the fight that my nuanced arguments came down to "it makes women feel bad" -- a petty reading of a grinding experience indeed. In our era of presidential gaslighting, of re-entrenched sexism and misogyny (what a joke -- as if it had ever been uprooted an inch), I don't want to talk to anyone who isn't being petty, who isn't thinking about the minutiae of daily life and how fucking irritating it is to deal with this shit all of the goddamn time. Mesle and Blackwood:

"The Neapolitan novels feel weirdly capacious to us because they have allowed space for ugly feelings to exist, and importantly not only in their fictional depiction. One thing that this ugliness has allowed us is new purchase on the experience of reading, interpreting, and practicing criticism as women. It seems to us, personally, and as women, that to love these novels is to hate how most everyone else talks, argues, and makes claims about them. In fact, to love these novels, as women, might be to hate everyone; that hate might be one of the best (yet still limited) tools we have to understand how gender continues, obstinately, to shape individuals' entrance into interpretation."

I haven't wanted to talk to anyone who isn't feeling petty about gender since November 9th. But I also don't want to talk to anyone who isn't feeling petty about class and race, and in the academy, I find that people are rarely petty enough, for my taste, about class, Mesle and Blackwood included (we do slightly -- only slightly -- better about dealing critically with race. And of course it needs to be said, over and over and over, that these are not extricable categories -- you can't talk about gender without talking about race without talking about class. Though you wouldn't know it from the constant headlines about Trump voters, the "working" class is not exclusively composed of angry white men).

Two things irritated me about Mesle and Blackwood's brilliant reading of being irritated by readings of the Neapolitan novels: one petty and one very large indeed. The petty (which is of course to say the still large): they read a scene in which "Lenu realizes that her entire critical and creative life might be 'reduced merely to a petty battle to change her social class,'" which is indeed a crucial moment. The Lenu who has changed her social class has this thought, yes, that the fight may have been "mere." But when I read this line, the affirmation that such a battle would be petty, all I could think of was the bitter catharsis I saw in some of my middle school classmates, listening to Everclear on the back of the bus that took us home from school, singing along with the lines, "I hate those people who love to tell you / money is the root of all that kills/ they have never been poor / they have never known the joy of a welfare Christmas." It's merely changing your social class once you've done it, but there's nothing mere about it when you're living day to day, bracing for the petty economic catastrophe that could ruin you at any minute. (Would such a change be "mere" to the Lila who had to stop her education after elementary school, who destroys her body and mind working in the sausage factory?) In the context of the novel, the "mereness" has to do with a failure to live according to revolutionary political ideals -- to fit the personal into the larger systems that shape it and to take on the larger systems rather than the "mere" individual life. But the novels also show us the consequences of living for those ideals in the story arcs of Pasquale and Nadia. The system doesn't change, the individual life is ruined or corrupted anyway.

What I love about these novels, what I haven't seen discussed yet in criticism about them (which could be my own blindness, because I keep reading the articles focusing on gender), is how they also capture the grindingness and pettiness of the experience of "merely" changing one's socioeconomic status, in addition to capturing the ways it can make one myopic and self-centered. Lenu is an outsider to the world of the Italian academy -- it is a shock to her when she is admitted, tuition-free, to a university in Pisa -- and she marvels at her professor's children, who seem to move so naturally in a world of ideas she has to work to come to grips with. The passages about the frustration of not knowing how to navigate new social spaces, of not understanding what the rules are -- that show how difficult it can be to figure out what the game even is, let alone how to play -- struck me so forcefully. (This is why, of all the novels in the world, I will always remain deeply, intensely attached to Great Expectations. Pip never really gets it -- the game plays him, and he doesn't understand anything about it until it's far too late.)

[This is also why I was thrilled to see The Goldfinch in person in the Hague; Donna Tartt's novel of the same name is a reworking of Great Expectations.]

What you learn is to shut up, to imitate, to not speak up when an idea or assumption seems wrong to you, because you know that any wrongness is always located in the things you learned as a member of other, unprestigious communities, from people with no status. Take, for instance, Lenu's account of a discussion of an article she hadn't read about Italian politics:

"The subject made me uneasy, and I listened in silence. ... I was informed about world events only superficially, and I had picked up almost nothing about students, demonstrations, clashes, the wounded, arrests, blood. Since I was now outside the university, all I really knew about that chaos was Pietro's [her fiancee] grubmlings, his complaints about what he called literally 'the Pisan nonsense.' As a result I felt around me a scene with confusing features: features that, however, my companions seemed able to decipher with great precision, Nino even more than the others. I sat beside him, I listened, I touched his arm with mine."

Nino, who comes from the same place as Lenu, understands the game faster than she does (or at least appears to), and we see her here in some ways trying to take a shortcut through him -- attaching herself to his body, desiring to take on some of his facility in this world of ideas through physical contact, the same way her husband Pietro, of that academic, petit bourgeouis class, provides her a way in.

The novels also beautifully, simply, killingly describe the ways that changing one's socioeconomic status can alienate you from your family and them from you, temporarily or permanently. Lenu's family is of course proud of her, but also resentful of her and ashamed when she brings her new realm to them. When she finally brings her higher-status fiancee home, she waits until the last minute to tell her parents he's coming, which causes the following scene with her mother:

"She attacked me in very low but shrill tones, hissing with reddened eyes: We are nothing to you, you tell us nothing until the last minute, the young lady thinks she's somebody because she has an education, because she writes books, because she's marrying a professor, but my dear, you came out of this belly and you are made of this substance, so don't act superior and don't ever forget that if you are intelligent, I who carried you in here am just as intelligent, if not more, and if I had had the chance I would have done the same as you, understand?"

I still have a hard time thinking about how angry I was with my family for not preparing me better for the violent competitiveness, for the disillusionment, for the fundamental pettiness, of social climbing via educational institutions in America. They couldn't have, of course, and it wasn't actually them I was mad at -- it was the people constructing and enforcing the rules of the game -- but that didn't make the conflict any less real. It didn't make it any easier to go home, to see the ideas and ways of knowing and cultural productions I was now supposed to scoff at, to be better than.

A petty incident I haven't let go of and will never let go of (the same way I will not let go of ending sentences with prepositions): in a creative writing class, a fellow student wrote a story about meeting an autodidact. It was, to my mind, a shitty, condescending portrait written by a shitty, overprivileged prep school kid. The professor praised it as a true portrait of what autodidacts are like. I fumed for days to myself about this and was never able to express how fundamentally gross the whole exchange was. It was so dismissive of this character, of their way of processing the world, which irritated me deeply because of how many autodidacts I grew up with, who were autodidacts because education is a class-based system even in our supposedly democratic nation. Of course you process the world differently if you have acquired knowledge without the guidance of institutions designed to shore up class differences, which are also gendered and raced differences. Why that should then become a source of bemusement for people with access to those institutions, a way to write cute stories about how smart and talented they are after all their years in those institutions...well. It's a thing I have no desire to reconcile myself to. (And, it needs to be said, this truly is a petty incident, compared to the serious aggressions my non-white classmates faced daily in virtually every classroom, every space on campus.)

So, the petty irritation with Mesle and Blackwood's reading: it's not petty enough about classed experience. The larger irritation: I want them to go further, to double down on claims they gesture toward or feint at here that they assert forcefully elsewhere. In a non-scholarly article, they argue that "taste is just another name for misogyny," but in this piece they argue that this claim, when presented "as a truth claim at the foundation of an argument rather than the argument itself...can't hold ... it is out of scale with itself." But of course this claim can and does hold, and can be backed up with all kinds of careful, rigorous scholarship, as can claims that taste is another name for racism and for classism. Take Michael Omi and Howard Winant on racial formation, "the process by which social, economic and political forces determine the content and importance of racial categories ... in the cultural realm, dress, music, art, language and indeed the very concept of 'taste' has been shaped by racial consciousness and racial dynamics" (qtd. in Bibby 493). Take basically all of Pierre Bourdieu's work, or the whole field of cultural studies, or race studies, or gender studies, or queer studies -- all of it provides more than ample evidence that taste is another name for oppression. I want Blackwood and Mesle to own this, to say, not just that taste is misogyny, but fuck the very idea of taste. It is worse than useless; it's violent.

I write "fuck taste," and take great pleasure in writing it, and mean it sincerely. And yet, as of April 2016, I am in a position to be the gatekeeper, the one who tells students that their ways of knowing are wrong, that there are other evaluative standards than the ones they know that they must apply if they want to enter a world of ideas. I spend a lot of time telling students that the ways they're used to reading literature will no longer work for them, at least not in my classroom. But I do what I can to explain that ways of knowing, ways of reading, are situational. They depend on communities and contexts, and the way they learn to read in the classroom isn't the only or even always the most desirable way to read.

When I teach, I focus my students' attention on particular texts not because I think they're objectively good, as if that's something that could ever be evaluated, but because I think they contain ideas that my students need to encounter, to think about, to wrestle with to live lives that don't remain petty and quotidian, even as they remain grounded in those categories. I don't want them to have to be trained into a new class, though I want them to have the tools they'll need if they want to fight that battle. I want to make their worlds bigger. I want them to think about the types of communities they want to create for themselves, at all scales. I want them to dream, and to create their own palimpsests, and pull together the texts and experiences and people that they need, that define them, that make them bigger and better versions of themselves, that add to their stories. This project seems so much more urgent than evaluative criticism ever has been or could be. That probably makes it utopian and quixotic. But I also know that already, for a student or two, this approach has mattered.

"Good" is a useless term; "worth thinking about" is better. I want to live in a world in which people say "that's not for me" rather than "that's objectively bad," where we ask "what do the people who it's for like about it? What's interesting about this object when I try to remove my ego from the conversation?" and so I do my best to create that world for myself and my students every day. I can't make anyone else dwell there with me, but I try to make it an inviting place.

IV. Syros and Lesvos: Re-enchantment

[I was a free [woman] in [Lesvos] / I felt unfettered and alive]

Like a lot of women, I've been trained out of feeling that self-expression is seemly or necessary. This happened insidiously in various complicated ways, most of them having to do with writing. I've always written -- I made picture books out of construction paper bound with masking tape before I understood the alphabet; in elementary school I wrote stories in which I was a genius child detective; as a teenager I wrote a ton of earnest poetry about how many feelings I felt (one of them even won an award and I got to read it at a public event -- unsurprisingly, it bummed the audience out); as a young adult I tried to write fiction but quickly felt that I would never be successful at it (one of the last pieces I wrote in fact was about my fear of failure, inspired by the panic attacks that a change in anti-depression medication caused during my junior year of college. It lives on online, because what is millennial self-expression if it's not on the internet?). I discovered uncreative writing; I started dating someone who believed that self-expression was essentially just narcissism. After college, I stopped writing anything that wasn't career-oriented. I didn't even journal for myself anymore.

Being trained out of your class, being socialized as a woman, means learning to distrust your instincts and to put aside the things that merely make you happy in order to make room for the things that are Important, according to Important People. This trip has been at some level about reenchantment, about following desire and sensation just because they exist and I exist. Because I fucking love existing, and I fucking love writing about existing. (Someone I dated briefly told me he liked being with me because I took so much joy in the things I loved -- I believe his exact words were "experiencing things with you is fucking exhilarating." It remains one of my favorite compliments, one that I try to live up to.)

Something that had been shifting inside of me for a while broke open when I read Maggie Nelson's The Argonauts last fall. The way that she used academic criticism to think about her life was so elegant and free and liberating. It made me want to write again -- to give shape to my thoughts other than the very specific shape required by academic writing. It made me want to think about living as a creative act. It felt like one while I was on Syros and Lesvos.

I captured some of what Syros was like for me here. I slept in; I wrote my academic writing; I swam in the sea; I drank ouzo and tsipouro and wrote my non-academic writing. I went for night swims and hikes and ate every fig I could find. I sat one day at the top of Ermoupolis, under pine trees overlooking the port and read Tribute to the Angels, book two of H.D.'s Trilogy.

Ermoupolis is named for Hermes. I had forgotten that Tribute opens with an invocation of Hermes:

Hermes Trismegistus is patron of alchemists;

his province is thought, inventive, artful and curious

Tribute is a book about reinvention, recreation after absolute destruction, pursued through writing. One of the central images is the vision of a holy woman, a palimpsest of Mary and Eve and Lillith and Isis and Astarte and Ashtaroth. The woman is described as "Psyche, the butterfly, / out of the cocoon." I don't believe in signs and wonders the way H.D. did, but, when I read those lines, a butterfly flew across my line of sight, and stayed, fluttering up and down on the wind until I finished the book.

no trick of the pen or brush could capture that impression

**

Lesvos was, if anything, more magical than Syros, which I didn't think was possible. I only saw a very tiny corner of the north of the island -- essentially just Molyvos and Eftalou, but it was more than enough. The hot springs in Eftalou alone...

On Lesvos, I started reading Alana Massey's brilliant and funny All the Lives I Want, and made a million notes in the margins that were all variations of "fuck. yes!" The title essay, about Sylvia Plath fangirls, is especially marked up. Massey argues that Plath's poetry and journals, and the fan art on display in certain corners of the internet, are "ongoing act[s] of self-documentation in a world that punishes female experience (that doesn't aspire to maleness)," which makes them "radical declaration[s] that women are within our rights to contribute to the story of what it means to be a human." Reading the final line of The Bell Jar ("I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart: I am, I am, I am."), Massey notes, it's difficult "to think of any line of thinking more linked to being a socialized female than to consider the declaration of simply existing to feel like a form of bragging." Massey stakes a claim for girlhood, for effusive emoting and navel-gazing introspection, as sites of strong affective attachments and sharp intuitions about the world that should be valued: "Young girls are smarter than they're given credit for, and more resilient, too. They like what they like for good reason."

In general the rating system on Airbnb makes me uncomfortable the way all rating systems make me uncomfortable, but my hosts on Lesvos wrote, "Erin is a joyful and adorable person." I was so tickled by their choice of words because they capture the spirit of girlhood that Massey champions:

"I want to call out to the girls who repeat Sylvia's poisonous directive, 'I must bridge the gap between adolescent glitter and mature glow.' This is a fallacy, a lie intended to kill the spirits of girls so that they might become what we have come to expect of women. ... Glitter is the unbridled multitudes of shining objects that have no predictable trajectory and no particular use but their own splendor. A glow is contained. Its purpose is to offer a light bright enough that those who bear it will cast a shadow, but not so bright that their features will come fully into focus. 'Never surrender your glitter' sounds like the cliche battle cry of a cheerleading coach or a pageant mom, but I still find it a suitable message for young girls."

My favorite beach in Syros was full of mica schist -- as you swam in the clear blue Aegean, the mica filled the water and glittered in the sunlight over your skin. I bathed in glitter every day on that island. Signs and wonders.

V. Zurich: Out of Line

In fifth grade, my teacher told my mother that I was a pleasure to have in the classroom. Without missing a beat, my mom replied, "You don't know what a viper you're nursing at your bosom." They were both right. I am joyful and adorable, and I am almost always, on some level, furious. (Someday I hope to work at Sam Irby’s school for girls with bad attitudes.)

I was made to feel unsafe three times on this trip: twice men followed me as I walked alone at night, and once a bus ticket taker didn't exactly assault me, but he didn't exactly not assault me. I expected things like this to happen on this trip, because they happen everywhere. But god. The way a patriarchal world will try to shut you down every time you try to take pleasure in it.

Maggie Nelson writes about the "many-gendered mothers of the heart” who help her live in the world; Massey writes about her famous friends (celebrities she's never met) who help her do the same. For me as for Massey, Courtney Love is one of those many-gendered mothers who helps me cope with the constant misogynistic violence of the world. Courtney was loud and messy and dramatic and ugly and gorgeous in the 90s, when I first became aware of her. Though I didn't exactly have the language or the concepts for it then, I felt the truth that Courtney embodied "female rage as ... the logical response to a hostile world,” as Massey describes her:

"When evil is done to a person, it gets under their skin, if there is enough of it, it'll sink down through the flesh and into the bones, becoming part of its target. For most of us, the pain is absorbed as poison rather than power. We see a world awash in women's blood and tears. We endure claims that the most profound kinds of pain are the exclusive possessions of men, that they are best equipped to make art from this suffering. Instead of bearing witness to it, we are asked to be killed by it, quietly if possible. But Courtney did nothing quietly." (Courtney: "honeysuckle / she's full of poison / she obliterated everything she kissed")

Like Massey, "I have not seen a fraction of the cruelty that the world is capable of, but I have trembled often enough in the aftershocks of my own resistance to a world built to break me to know that female brutality is not just an acceptable response, it is the most sensible one, too." I saw Courtney in the play Kansas City Choir Boy at the Oberon theater in Boston a few years ago. The play was...not for me (it was for a certain kind of creative white man), but Courtney was. She passed so near my seat at one point I could have reached out and touched the tiny flower tattoos on her arm, could see the glitter eyeshadow she wore. I was so, so happy sharing space with her. I love that bitch. I love her for being angry and messy and never apologizing. I'll hold that moment in my heart forever.

Of course, to refuse to behave respectably, according to gendered, classed, raced codes, is a particularly fraught survival strategy for people who inhabit bodies that tend to get disciplined and punished. (Just look at the police response to an actual fucking Nazi rally and compare the way they’ve treated peaceful black protestors.) I read a lot of books by white women on this trip -- actually, a lot of books by white women my age, who spent their late teens/early twenties in and around New York -- in part because I wanted to navel gaze, to dive into my own experiences and identity. But of course identity, experience, only happen in relation to other identities and experiences. The women I've been reading have suffered, have felt pain, have expressed it in ways I've found compelling. But they're also insulated from some types of pain, the same way that I am, by my whiteness, by what some people read as "adorableness" or attractiveness. It's easier for me, and for the women I've been reading, to access some survival strategies than it is for other women. White girls can act out with relatively less punishment than black girls; those of us who write/think for a living often have access to grants and funding structures that allow us to be selfish, to take the time to pursue ideas.

I stopped in Zurich for a day and a half on my way back to Amsterdam because it is where H.D. lived in the last years of her life, where she wrote a few of her major works. It is also near where my paternal ancestors are from, so it was a chance to take a selfie in Kappeler alley and Kappeler park.

I thought a lot about privilege in Zurich, one of the most insanely expensive cities I've ever visited. The places where H.D. lived and wrote in Zurich are gorgeous and peaceful.

[The Klinik Hirslanden, where H.D. spent her final days]

The peace she found there was hard fought, and it makes me happy to know she was able to make that place for herself. But she was able to make that place because of her heiress lover, her whiteness, her access to certain kinds of privileged spaces.

In Zurich I started How to Murder Your Life by Cat Marnell (which is such a compelling read). It's another story of a privileged white female writer, but it's also the story of an addict. And oh my god, if you want your heart broken, read Marnell's description of what her parents did with her zine. The way they shut down her means of self-expression, of effusion, of girlish excitement and emotion, is brutal, and brutally common for girls, even if they're rich, even if they're white. Marnell, like Love, survives by acting out, by refusing to conform, to be quiet and docile. It's not necessarily a good strategy -- Marnell's is not a happy story, and it's questionable how long she will continue to survive. But it is a significant strategy, a way to protest, "the logical response to a hostile world." (It can't destroy you if you destroy yourself.)

[There is a beautiful cemetery across the street from the Klinik Hirslanden, full of statues of women like this. They mark women whose lives are long over, who may or may not be remembered. They seemed to me both tragic and defiant, poignant symbols of loss and endurance.]

***

What does it mean for me, a white cisgender woman, to remain invested in the category "woman" now? What does it mean to claim my experiences, my existence as important, when I exist as a white woman in a country where white supremacism is newly emboldened and sanctioned? (And, to borrow a phrase from Mesle and Blackwood, let’s be crystal fucking clear about this: white supremacism has always been there. It’s structurally a part of our country in a million different ways. What we’re seeing today isn’t surprising or new; it’s the logical outcome of our failure to confront how white people maintain oppressive structures because we benefit from them.) As Mesle and Blackwood argue in their reading of Ferrante,

"it is worth saying that 'woman' is obviously a troubling category. 2017 is a year when the world has emphasized both how radically women are vulnerable as women, with pussies to be grabbed, and also has made the violence that white, straight, middle-class women do to others crystal fucking clear. (Trump's voting block depended precisely upon the pettiness of white women.) Further, we can't even use the word 'woman' without mobilizing a language that is inherently false, and heterosexist, in its understanding of what it means to be human. Perhaps 'woman' is a word that should have no force in criticism. Many people think this, and we see their point. Yet we - we, the writers of this piece -- are uncomfortable with the way this formulation allows human knowledge, here literary criticism, to hopscotch yet again over the responsibility to understand the particularities of women's experiences, in the way that science and medicine and economics and history often have done. ... This is the tension of the sign of 'woman': that it is out of scale, simultaneously universal and particular, simultaneously useful and an obstacle, outmoded. We have to talk about it, and yet can't."

I don't believe that there are any universal or essential experiences of womanhood. "Woman," "female" are of course socially constructed categories, not empirical realities. But the experience of being socialized as a woman does things to you. It creates problems and opportunities and frustrations and acts of violence and intense, intense pleasures. It creates the particularities of individual lives. The experiences of people who live as women matter to me, fundamentally and completely. My attachment to the sign "woman" is serious and real, even as it's fraught and falls apart as soon as I start to interrogate the category with any rigor. Perhaps "woman" is simply the sign for what Mesle and Blackwood identify as "a kind of ecstatic bitterness that is the opposite of consensus making or persuasion. It is aligned with the lived-ness of gender, with the deauthorization of all those whose lives never stand as common sense. This bitterness reminds us that it is always a privilege to have the luxury of leaving pettiness behind."

VI. Missouri: Enlargement

This has been a hard year, personally and politically. I love the new life I started making when I accepted my first tenure-track job in the spring of 2016, but making a new life is difficult and draining work. I think I would have been emotionally tired no matter what. But this was also a year in which I decided I'm going to keep consciously rejecting the versions of adult female life that are legible to people, which is right for me but also a difficult thing to do. And, of course, it was the year of the worst imaginable presidential election outcome, and of moving to a state where the state government is actually worse than the current presidential administration. It's hard to realize how many of your neighbors are contemptuous of you just because you're female, and of your friends because they're trans, gay, bi, non-binary, not white, an immigrant, economically disenfranchised, neurodiverse, ill, and on and on and on. By the end of the spring semester I was tired and emotionally sick in a way I've never been before. Planning this trip was a way out of that structure of feeling for me -- it was a way to chart a new course, build a new structure, enlarge the space in which I feel safe and free to exist.

Years ago, when Sheila Heti's How Should a Person Be? first came out, I fell deeply into that book and spent a lot of time thinking about it. I copied the protagonist and made a mental catalogue of what non-material things I had at my disposal. I wrote it down on an abandoned blog somewhere. I'd forgotten about it until I read re-read this passage in Tribute to Freud:

"We [H.D. and Freud] had come together in order to substantiate something. I did not know what. There was something that was beating in my brain; I do not say my heart -- my brain. I wanted it to be let out. I wanted to free myself of repetitive thoughts and experiences -- my own and those of many of my contemporaries. I did not specifically realize just what it was I wanted, but I knew that I, like most of the people I knew, in England, America and on the Continent of Europe, were drifting. We were drifting. Where? I did not know but at least I accepted the fact that we were drifting. At least, I knew this -- I would (before the current of inevitable events swept me right into the main stream and so on to the cataract) stand aside, if I could (if it were not already too late), and take stock of my possessions. You might say that I had -- yes, I had something that I specifically owned. I owned myself. I did not really, of course. My family, my friends and my circumstances owned me. But I had something. Say it was a narrow birch-bark canoe. The great forest of the unknown, the supernormal or supernatural, was all around and about us. With the current gathering force, I could at least pull in to the shallows before it was too late, take stock of my very modest possessions of mind and body, and ask the old Hermit who lived on the edge of this vast domain to talk to me, to tell me, if he would, how best to steer my course" (17-18).

I got to pull into the eddy and take stock this summer. I am grateful; I am well supplied. I am ready to put my oar back in, which I must, because the current is still gathering, and we all have to do our individual parts to deal with the destruction that is here and that is coming. I am ready. I am, I am, I am.

0 notes

Text

Heaven

When I imagined what Greece would be like, I imagined this.

There’s a beach near where I’m staying that, if you get there early enough, you can have basically to yourself for a good part of the morning. The water is just cold enough and perfectly clear, and the sand is full of tiny particles of mica that make it glitter through the already glittering water.

Syros is dry and mountainous, with ancient towns cut into hillsides and tiny roads full of sharp switchbacks. Everything shuts down between 3 and 5 for an afternoon rest. All of the restaurants in the town I’m in are so close to the water they’re almost in it.

There’s a kind of aloneness that is indulgent and voluptuous, that is like swimming in the calm water I’m surrounded by. I have it here.

I’m spending a lot of time with the slow and sensuous pleasures of the world. I sat under these pines for I don’t know how long, just breathing their smell until I understood the existence of mastiha. I’m spending hours on my patio, staring at the way the blue of my neighbor’s shutters matches perfectly the blue of the Aegean, and doing the kind of writing, personal and professional, that is only possible for me when I have the space and time to spread out mentally like this.

One of the town’s mini marts had fresh figs today,

and the colors matched some of the flowers I see on the walk there.

I’m ruined for regular life.

0 notes

Text

Corfu/Kerkyra

The trip I’m on has multiple functions, one of which is to make a literary pilgrimage. I’ve been loosely following some of the threads of the poet H.D.’s life, including a significant event on Corfu, for reasons that I’ll write about later (there are many, it’s complicated, I’m not sure why I’m following them now, but here I am).

I am both glad I’m here and I can’t wait to leave. The island of Corfu is ridiculously beautiful --

and ridiculously cheesy --

(if you listen closely you can hear the Muzak version of “The Girl from Ipanema” coming through the beach bar’s sound system.)

Because my travel funding came later than expected, I didn’t book a hotel room until much too late in the season, which means I wound up staying in Sidari rather than my desired destination of Corfu town. (Had I understood the domatia concept/system, this would have been a very different trip.) Sidari is, essentially, the British version of the Jersey shore. (”Sidari is no good,” according to an Airbnb host in Corfu town, and I can’t say I totally disagree.)

Think Wildwood -- families on holiday, kids building sandcastles, teenagers cruising each other, everyone sunning themselves into a radioactive hue as if news of skin cancer failed to travel this far, empty yet deafening nightclubs straight out of the Inbetweeners movie. Sidari may have once been a Greek town, but it is now little Manchester.

Every restaurant serves buttys and toasties and Irn-Bru and Guinness. You can’t swing a beach towel without finding a place to watch a football game, and every night, although my hostel is decently far from the town center, I’m lulled to sleep by the sounds of karaoke and kids racing scooters down the main drag.

There are things about Sidari that are charming. Everyone I've met, including some of those British tourists, has been lovely. When I was confused about how to find my bus stop, the driver called ahead to my hostel to confirm things with the owner, Angelica. ("Ah, Greek men," said Angelica when I arrived. “[noise somewhere between amusement and resignation and frustration] — they like pretty girls. These bus drivers, they are not always so nice, yes?") Angelica herself has been delightful. She's told me a lot about Sidari and the guests she sees and Germany, where she was born and raised, and what it's like living through the current economic crisis ("It's a shit time. But at least on Corfu people can have chickens and gardens, so it does not look so bad here. But in the cities..."). Indeed, one day at a mini mart the clerk was clutching something to her chest. I didn't think much of it until a baby chick poked its head out of the towel she was holding.

I've been delighted every time a clerk or waiter is amused by my parlor trick of having sort of learned how to pronounce thank you correctly in Greek, but disappointed to realize it really is only the men who find this paltry accomplishment charming. I keep thinking of the story of the hostel guest of Angelica's who, every morning would come up to the kitchen, spread his arms wide, and proudly greet everyone, "Calamaris!" (”good morning” = “kalimera”). When I can't take the tourist kitsch anymore, I’ve gone for runs in the gorgeous countryside, on tiny roads that wind through olive groves and empty buildings and subsistence farms of goats and chickens and orange trees and squash vines and bee hives and tiny tavernas where old men sit outside and smoke and drink (these men, they are also very friendly).

I’ve also been escaping to Corfu town as much as possible, but the bus system here is chaotic, to put it nicely. The town itself is only 30km away, but it takes an hour and a half to get there. (Buses are giant touring buses that barely fit on the tiny mountain highways; bus stops are unmarked and placed seemingly at random; tickets are sold on the bus, meaning you often sit and wait at a stop for 15 minutes for everyone to get paid up; schedules are mostly followed, kind of, but also you’d better be at your stop early just in case, but also be ready to wait for late buses, because they are always late.) On my bus this morning, the ticket taker asked if I would volunteer to give him a massage, then attempted to give me a massage, and then asked if I’d like to kiss while grabbing the back of my neck (”My name is Philip, would you like to kiss?” -- verbatim pickup line). These Greek men...

Of course, one of the other functions of this trip is to get myself to write, and Sidari is sort of a perfect place for that. There is nothing to do, once the novelty of people watching wears off (I am not trying to tan myself into a radioactive hue, so that pastime is out), and the concentrated thinking time has led to some realizations about what I’m trying to do in the book chapter I’m writing and in the larger book project as a whole.

And the pilgrimage has been significant -- it meant something to me to be in the places in Corfu town that mattered to H.D.

[Corfu town near H.D.’s preferred hangouts]

Still. Corfu is one of the places where Odysseus was briefly stranded, and while he found its inhabitants welcoming, he was happy to leave. I’m looking forward to moving on to my next island too.

0 notes

Text

Roman Holiday

I had a glorified layover in Rome yesterday, and it was incredible.

I was afraid of Rome -- everyone I talked to said it’s awful in the summer, and the pickpockets are terrible, and it’s generally an unbearable place in July. (”Everyone there is crazy right now,” according to a Roman I met in Prague.)

But aside from the heat, which was real, none of the other warnings were borne out. I walked through the city all day long because I just couldn’t stop gawking at the scale of the architecture.

I tried to capture what it’s like to round the corner onto the Piazza Venezia and to be confronted with the Museo Sacrario delle Bandiere, but pictures can’t do it justice.

The Foro Romano,

the Pantheon,