Text

Slaty-backed Gull

Larus Schistisagus

A rotund, dark-backed gull of northeast Asia. Legs bright to rich pink, brightest in high breeding condition. Eye pale yellow, sometimes with flecking, rarely dark (Ayyash 350; Howell and Dunn 440). Often structurally distinctive, with short wing projection, long goose neck and round, sagging lower body (Adriaens 264; Ayyash 350). Adults have extensive white portions to upperparts and remiges. Broad tertial and scapular crescents. Large apicals, shrinking with wear. Fairly broad trailing edge to secondaries and inner primaries, appearing uneven at times, especially towards inner primaries, like the slate of the remiges was hurriedly coloured in with felt marker on either side of the rachis (feather shaft). White tongue-tips on p6-p7 or p8 (Ayyash 357) creates a string-of-pearls. Variably large p10 mirror, sometimes smaller mirror on p9.

Citations

Ayyash, Amar. "The Gull Guide: North America." Princeton University Press, 2024.

Adriaens, Peter, et al. "Gulls of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East." Princeton University Press, 2022.

Howell, Steve N. G., Jon Dunn. "Peterson Reference Guide to Gulls of the Americas." The Peterson Reference Guide Series. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007.

0 notes

Text

Thayer's Gull

Larus glaucoides thayeri

A four cycle gull similar in size to California Gull (Howell 392). Small individuals with long wing projection and cute appearance (Adriaens 188). Larger birds approach American Herring Gull in size and structure; the bill however is rarely as robust, lacking a pronounced gonydeal angle. The largest male-type Thayer’s Gull can outsize female-type American Herring Gull (Ayyash 398).

Yellow bill with small gonys spot in breeding condition, becoming pale with a yellow patch on the culmen. Dark eye, though variable. Legs and orbital ring rich pink in high breeding condition, duller pink in low breeding condition.

White body with gray upperparts similar in shade to Glaucous-winged Gull. In basic plumage, head, neck and chest mottled dusky, often with greater concentrations on hindneck. Varying amounts of streaking on head. Dusky patterning replaced by white in alternate plumage.

One cannot overestimate the incredible variability of primary patterns within this taxon, and the dividing line between thayeri and kumlieni has not been fully ascertained. However, learning to distinguish between typical thayeri and kumlieni wingtip patterns is an important first step in trying to reconcile edge cases.

Wingtip Patterns

p10 has partial, complete or absent subterminal band. Large mirror commonly extends to both sides of feather (Ayyash 398). Variably sized medial band (visible on open wing) slopes proximally on outer edge of outer web, forming a dark line that reaches the primary coverts.

p9 highly variable. Mirror can be restricted to inner web or broken in half on either side of rachis, with the outer web portion usually not reaching the outermost edge. Subterminal band present when mirror is at its largest. In more pigmented birds, subterminal band and outer edge of outer web merge, forming a thayeri pattern. Some individuals have medium-sized mirror enclosed in black (Ayyash 398). Medial band, variable and sometimes absent, slopes proximally, forming a dark line that sometimes reaches primary coverts. Rarely p9 mirror absent.

Subterminal bands and tongues tips from p8-p6 or p5, with apicals sometimes eating into rachis (these individuals usually have larger tongue tips) (Ayyash 398). p4 can have small dark markings, usually on outer web (Ayyash 398). p5 subterminal band sometimes broken or absent. Rarely a broken p6 subterminal band, faded in appearance (Ayyash 398).

Juvenile to First Cycle

Juvenile to First Cycle

Head, neck and underparts ranges from milky grey brown to dark brown typical of American Herring Gull; streaked or mottled whitish (Howell 476).

White base color with variable extent of dark barring to ventral area, undertail and uppertail coverts.

Primaries the darkest feather group, followed by tertials and secondaries (Ayyash 400). Paler individuals suggest Kumlien's Gull, except remiges noticeably darker than rest of plumage, especially primaries. Primaries and greater primary coverts usually have pale tips, more extensive on paler individuals.

Incredible variation in upperpart patterning, overlapping with American Herring Gull and other taxons. Regularly has thicker, whitish margins on scapulars and coverts than American Herring. This variable patterning, even within a single plumage, and contrasting with whitish margins, can make upperparts appear messy, especially on secondary coverts at rest.

Scapulars can have dark centers, creating a scaly appearance; can be slightly notched in a holly pattern, like typical American Herring Gull. Other scapular patterns include:

Center shaped like a diamond, spade, anchor, or upside-down three-point crown (Ayyash 400; Howell 476).

Brown basally with dark subterminal band

Barring or checkered pattern on greater coverts increases in intensity proximally, nearest the tertials.

Tertials dark basally, with variably notched distal edge.

On upperwing, darker outer webs on outermost primaries, forming venetian blind. Dark primary tips merge with outer web on outermost primaries. Dark primary tips decrease in size proximally along wing, sometimes becoming restricted to outer web, joining dark line running along rachis distally.

Secondaries dark brown with pale leading edge.

Underwing coverts concolorous with other body feathers, sometimes with barring.

Underwing primary and secondary greater coverts paler gray brown; remiges greyish, can look silvery in direct lighting.

Pale underside to primaries helps rule out typical American Herring Gulls.

Axillaries with variable amount of barring or marbling.

Tail usually dark brown with a thin, notched or absent tail tip. Variable amounts of barring or marbling basally, usually more extensive on outer webs of outermost rectrices. Some individuals have solid dark tail.

Bill remains dark through the winter months, sometimes with flesh pink basally. Legs dirty pink to pink. Eyes dark.

First alternate scapulars pale gray to brownish gray, with thin undulating markings, barring or anchor patterns(Howell 476); can be solid gray.

Plumage bleaches whitish into spring, contrasting with darker remiges.

Second Cycle

Head, neck and underparts mottled and streaked brownish gray and whitish. Sometimes has short postocular line (Ayyash 402).

Scapulars range from uniform gray in advanced individuals, an admixture of gray with brown markings, to thinly barred on a whitish base color.

Upperwing coverts milky brown to dark grayish brown, contrasting with gray scapulars on advanced individuals. Median and lesser coverts, when barred or checkered on whitish base color, contrasts with plainer or marbled greater coverts. Greater covert patterning, when present, increases in extent proximally along wing.

Tertials with dark centers, variable amounts of marbling on distal margins. Less advanced individuals can show light barring on plain background (Ayyash 402).

Dark outermost primaries with venetian blind pattern, sometimes with p10 mirror.

Wing panel formed by innermost primaries, contrasting with darker secondaries, outer primaries and often the primary coverts.

Whitish distal margins to outer primaries and primary coverts reminiscent of first cycle, absent on more pigmented individuals.

Variable amounts of marbling along trailing edge of secondaries and innermost primaries. Secondaries with dark centers.

Ventral area, uppertail and undertail coverts variably barred with white base color.

Tail dark with variable extent of white and marbling basally; patterning often most extensive on outer webs of outermost rectrices. Tail can also be solid brown or dark. White tail tip ranging from thick band to thin line or absent.

Most individuals develop dark bill tip with flesh pink base in winter, not clearly demarcated as in American Herring Gull.

Legs pink. Eye color dark to dirty lemon. Orbital ring can be pinkish in summer (Howell 477).

Third Cycle

Third Basic plumage like definitive basic with immature characteristics. Delayed individuals can superficially resemble second cycle (e.g. dark brownish outer primaries with small p10 mirror), while advanced individuals become difficult to distinguish from later age groups.

Head, neck and underparts white with brown markings. Streaking on head becomes smudging on lower neck and breast, concentrated around hindneck. Smudging more extensive than adult, sometimes reaching belly and flanks. Brown markings sometimes present on ventral area. Rump white.

Upperparts adultlike gray with some brownish tinge throughout, less noticeable in advanced individuals. Sometimes with remnants of brownish marbling on greater coverts. Tertials gray with broad white margins distally, often with dark brown centers or markings.

In flight, upperwing secondary coverts grayish and variably washed in brown and dark markings, but can approach adultlike gray.

Secondaries gray with white trailing edge, often with brown tinge and dark bases or markings to multiple feathers. White trailing edge on secondaries continues to inner primaries.

Usually with concentration of dark markings on primary coverts and alula, especially outermost greater primary coverts.

Like secondaries, innermost primaries gray with white trailing edge.

More extensive pigmentation on outer primaries than adults, usually on outermost 6 primaries, varying from dark brown to blackish. Pigment often reaches primary coverts on p7-p10 (Ayyash 403). P10-p6 with paler inner webs, creating venetian blind pattern. Often dark subterminal band on p5, at times restricted to outer web, with dark line running proximally along rachis.

Apicals smaller than adult, can be absent.

Mirror on p10. p9 sometimes with thayeri pattern or small mirror (Ayyash 403).

On underwing, coverts white with variable amounts of brown wash.

Secondaries and inner primaries pale silvery with trailing edge, sometimes washed brownish. Venetian blind of outer primaries visible on underwing, appearing diluted.

Tail can be solid dark with pale tip, have dark distal band, or be mostly white with dark markings; dark markings often concentrated on central rectrices (Ayyash 403).

Eye usually dark, can be pale lemon. Bill varies from pale flesh with dark tip to greenish yellow with distal markings and orange smudge on gonys. Legs pink to purplish pink.

Third alternate plumage has reduced brown smudging on head, neck and underparts. Upperparts gray.

1-2 tertials replaced (Pyle 688), gray with broad distal margins, contrasting with less advanced third prebasic feathers. 1 or more central rectrices may also be replaced (Pyle 688).

Smaller apicals can be lost to wear (Howell 477).

Bill brightens to adult yellow with red gonys spot and either dark tip, distal band or subtle markings.

Forth cycle individuals may retain dark markings on alula, primary coverts and rectrices (Pyle 689).

Adult (Definitive) Cycle

White bodied with medium gray upperparts in definitive basic plumage. Brown to dusky patterning on head usually more streaked, becoming smudgy on neck and upper breast.

Broad tertial crescent and smaller scapular crescent. Secondary skirt often hidden.

At rest, pale inner webs of outer primaries create white 1-3 "hooks" running along upper portion of primary projection (adriaens 188).

Primaries black to slaty with white apicals.

In flight, upperwing coverts gray.

Secondaries and inner primaries gray with white trailing edge.

Dark pattern usually on 6 outermost primaries (p5-p10), with p5 having subterminal band or dark marking usually on outer web. Venetian blind pattern formed by darker outer webs. (See Wingtip Patterns for more information.)

On underwing, coverts white. Secondaries and inner primaries pale silvery with trailing edge. Dark patterns on outer primaries diluted from below, with subterminal portions often forming a band that runs along outer wing.

Medial portion of inner webs of p10 and often p9 appear washed out like ink.

Bill greenish yellow in low breeding condition, with yellow patch on outer culmen; some individuals have dark distal markings. Small red gonys spot. Gonys angle said to be less pronounced than other large white headed gulls, but subject to individual variation.

Legs pink or purplish pink. Orbital greyish to dull pink.

Hood pattern is replaced with white in third alternate plumage.

Bill brightens to yellow with pale nail and small red gonys spot. Orbital pink to purplish pink. Legs richer pink.

Citations

Ayyash, Amar. "The Gull Guide: North America." Princeton University Press, 2024.

Adriaens, Peter, et al. "Gulls of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East." Princeton University Press, 2022.

Howell, Steve N. G., Jon Dunn. "Peterson Reference Guide to Gulls of the Americas." The Peterson Reference Guide Series. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007.

Pyle, Peter. "Identification Guide to North American Birds: Part 2." Steve N.G. Howell, Siobhan Ruck, David F. Desante. Slate Creek Press, 2008.

#birding#birds#birdwatching#gulls#larus#bc#bird#molt#moult#larusglaucoides#larusglaucoidesthayeri#thayersgull#icelandgull

1 note

·

View note

Text

Franklin's Gull and Laughing Gull Chart

This chart will eventually end up in my Gullable app.

Thanks to Cam Nikkel and Joseph Bourget for allowing me to use their images in this project.

#franklins gull#laughing gull#seagull#gull#birds#birding#leucophaeuspipixcan#leucophaeusatricilla#gullable

1 note

·

View note

Text

Primary Patterns in The Iceland Gull Complex

Not by any means exhaustive, but should help with distinguishing between typical Iceland, Kumlien's and Thayer's Gulls.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western Gull

Larus Occidentalis

Large, thickset gull with white body feathers. Bill is bulbous compared to Glaucous-winged, more slender in females. Back slaty gray, outer primaries black-tipped. Juveniles start off sooty brown to grayish brown, pale outlined scapulars and coverts giving it a checkered or scaly appearance. Hybridizes with Glaucous-winged in the Juan de Fuca Strait, the northernmost range for this species.

Two subspecies: L. o. occidentalis to the north and L. o. wymani to the south. Nominate occidentalis has slaty gray upperparts, while wymani has slaty black upperparts and is smaller. Definitive basic head markings on northernmost populations may be due to hybridization with Glaucous-winged Gull.

Molt and Development

The following, unless otherwise specified, refers to both subspecies (L. o. occidentalis and L. o. wymani). Past attempts have been made to classify immature birds by proportions of “gray” and “brown” types (Howell and Dunn, Gulls of the Americas), but this does not appear reliable. I am afraid to even bring up introgression between the two subspecies, and Glaucous-winged Gull influence in northern populations.

Juvenile to First Cycle

Juvenile plumage sooty brown to grayish brown, uncommonly blackish brown, with variable amounts of whiteish flecking. Dark base color to most body feathers (head, neck, mantle, chest, flanks and belly), with darker concentration around face. Lower body variably patterned. Some individuals are uniformly brown into ventral region, others with white base and dark barring around vent, sometimes extending up belly or towards breast; these areas can also lack barring, instead being all white. Tail coverts with white base color and variable amounts of dark barring. Scapulars and upperwing coverts with whitish or buff margins, creating a scaly appearance; feather pattern ranges from having smooth dark centres to being heavily notched, creating untidily spotted pattern on secondary coverts. The greater secondary coverts dark basally, with barring increasing proximally along wing. When notching is extensive, greater covert panel has messy white band. Tertials dark basally, contrasting with lighter, patterned upperparts. Tertial pattern on distal edge variable, from a thin line and or with slight notching, to mostly white eating into feather base, creating a pseudo-tertial crescent. At rest, dark secondaries with pale trailing edge forms a skirt, contrasts with lighter, more patterned upperparts. In flight, trailing edge decreases in extent distally, disappearing almost completely by innermost primaries. on upperwing, all primaries uniformly dark on darker individuals, with minimally paler basal portion to inner webs; lighter individuals have a slight window. Primary coverts and alula dark with minimal, if any, pale margins. Lighter individuals have slightly lighter primary coverts proximally. On underwing, pale gray remiges contrast with darker auxiliaries, lesser and median coverts. Outermost primaries tend to have darker tips and leading edge, but be careful of underwing reflection. Tail dark like other flight feathers, with thin white distal edge, uncommonly with subtle notching; sometimes white and or barring basally on r6. Bill black with flesh pink basally, increasing in extent distally over first cycle. Flesh pink legs, some having dirty aspect [1].

First prealternate molt proceeds from late summer and early fall into spring, replacing body feathers and scapulars, sometimes upperwing coverts [2]. Scapulars vary from brownish gray with buff or pale tips with dark basally or streaked along rachis, to dark brownish gray with minimal patterning. Body feathers variably mottled sooty brown to grayish brown, becoming increasingly pale through winter. Low quality juvenile flight feathers and upperwing coverts become paler through bleaching and abrasion, contrasting with neater first alternate and second basic feathers.

Second Cycle

Second basic plainer and more diffuse than first cycle. Considerable variation within this age class, and issues arise when trying to distinguish between more advanced second prebasic and second prealternate feathers. (e.g. Second prebasic and prealternate molts overlap in late summer in northern California [3].) Upperparts range from grayish brown to brownish slate. On upperwing, plain greater coverts have varying degrees of diluted barring, vermiculation and pale margins, concentrated on innermost coverts. Tertials variably white on distal edge, with faded dark markings. Body feathers mottled pale and sooty gray or brownish gray. Remiges variably grayish brown overall. Dark secondary bases, outer primaries and primary tips like first cycle. Some individuals have a fairly advanced, broad trailing edge to secondaries and inner primaries [1]. Dark tail with thin white tip which is quickly lost to abrasion.

Second prealternate molt commences during late summer and early fall, replacing most body feathers and variable amounts of upperwing coverts, especially median coverts. Scapulars slaty gray with white crescents on advanced individuals, with some brownish wash. Body white and often mottled grayish to grayish brown. Sexually mature individuals have yellow bill with dark tip and gonys spot during breeding season, whiles others have either a flesh bill with dark tip or a dark bill with flesh basally. Bill color regresses by winter.

Third Cycle

Third basic plumage adultlike with immature characteristics. Advanced individuals have slaty gray upperparts with well-defined crescents and trailing edge to secondaries, with brownish undertones sometimes making said upperparts appear darker; body feathers largely white with dark smudging. Less advanced individuals have brownish tinge to upperparts, especially median coverts. Variable brownish patterning on underwing coverts. Hormonal changes throughout the third cycle can result in a mix of 2nd cycle type and adultlike patterns along the same feather tract, most notably on the primaries. Typically, inner primaries more gray with broad white tips and variable dark markings, dark line along rachis. Outer primaries darkish or black, sometimes with small apicals that abrade quickly; rarely with small p10 mirror. Primary coverts roughly reflect pattern of corresponding primaries (e.g. gray primary coverts over gray primary window). Tail white with variably complete band, advanced birds showing minimal to no markings. Bill becomes brighter yellow during breeding season, at times with black tip or distal markings, and small to complete gonys spot. Orbital yellow. Eye whitish yellow to olive.

Differences between third prebasic and third prealternate body feathers not fully delineated. Through late summer and early fall, some birds lose their dark markings, becoming quite difficult to distinguish from adults. Some birds continue to have dark markings, even having a semi-hood. Bill regress in nonbreeding season to being largely black with flesh basally to flesh with black tip or distal markings.

Fourth/Adult (Definitive) Cycle

Definitive basic achieved in forth prebasic molt. White body with slaty gray (occidentalis) to slaty black (wymani) upperparts. White scapular and tertial crescents, broad trailing edge to secondaries and inner primaries. Variable black subterminal band on p5, sometimes on p6 or higher. Black on p7-p8 often reaches primary coverts [1]. White apicals and small p10 mirror, rarely smaller p9 mirror. On underwing, gray remiges and black outer primaries contrast with white auxiliaries, lesser and median coverts. Eye whitish yellow to olive. Orbital deep, at times orangish, yellow. Legs sometimes develop yellow tinge for brief period during breeding season.

Definitive alternate body feathers at times impossible to distinguish from definitive basic. Head and upper body markings observed in some birds in late summer into fall, abrading quickly to all white. Northern populations have denser markings, which might indicate hybridism with Glaucous-winged Gull.

Citations

Ayyash, Amar. "The Gull Guide: North America." Princeton University Press, 2024, pp. 318, 322, 324.

Howell, Steve N. G., Jon Dunn. "Peterson Reference Guides to Gulls of the Americas." The Peterson Reference Guide Series. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007, pp. 446.

Howell, Steve N. G., Chris Corben. "Molt Cycles and Sequences In The Western Gull." Western Birds. 31, 2000. pp. 39.

#birding#birds#birdwatching#gulls#larus#bird#molt#moult#larusoccidentalis#western gull#westergull#seagull

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heermann’s Gull

Larus heermanni

Second cycle in appearance, but primaries are being replaced, commencing third prebasic molt.

A gorgeous, medium sized gull with slaty gray upperparts, gray body and white head in alternate plumage. Primarily coastal[2], breeding in Mexico and wintering as far north as British Columbia. Has a restricted breeding range, with around 95% of the population nesting on Isla Rasa in the Gulf of California[3][4], making it particularly vulnerable to human disturbance and environmental changes.

Molt and Development

Juvenile to First Cycle

Juvenile plumage chocolate brown to sooty brown overall. Variably extensive pale margins to scapulars, upperwing coverts and tertials, which abrade quickly. Scaly appearance, on rump and tail coverts, sometimes on undertail and flanks[6]. Blackish legs and dark eyes. Bill blackish, with dull pink increasing basally. Darkish remiges and tail with very thin pale edges, disappearing on outer primaries[1].

Postjuvenile molt (more study needed to rule out overlapping preformative and prealternate molts), variable in extent, including most upperparts and often a few tertials[5]. The extent of this "molt" generally increases towards lower latitudes, with advanced individuals replacing any number of primaries, secondaries and or rectrices[6][7]. Replaced body feathers are grayer than juvenile plumage, like pencil lead, and lack scaly appearance.

Second Cycle

Second basic plumage like first cycle, with more dark gray throughout, lacking pale edgings. Some upperparts can be slaty gray, and advanced individuals can have white speckling on head. Bill tip black with orangish tinge distally, greenish gray basally.

Second prealternate not as extensive as previous inserted molt(s), although can include inner rectrices[1]. Upperparts a mix of adultlike slaty gray and immature sooty brown, sometimes with white crescents to tertials and or scapulars. Less extensive trailing edge to inner remiges and tailtip compared to adults[1]. Variable amount of white mottling on head, sometimes almost completely white. Sexually advanced individuals can have red bills with black tips.

Third Cycle

Third basic variable, with some individuals looking adultlike or second basic in aspect. Individuals similar to second cycles tend to have more clearly defined scapular and tertial crescents, although not as distinct as in adults. Head pattern ranges from mostly dark gray to mottled dark gray and white, too dark and undefined for adult, with faint eye crescents. Adultlike birds with a brown tinge throughout suggests third cycle; however, worn primaries on adult types can appear brownish, and adults can have a faint brownish wash[6]. Eyes dark brown. Orbital ring gray to greenish[1]. Bill orangish with greenish gray basally, black tipped.

Third alternate plumage tricky, and some birds may defy ageing. Look for brownish wash and thinner edge to remiges and tail. Bill red with reduced black tip.

Fourth/Adult (Definitive) Cycle

Fourth cycle similar to definitive cycle. Slaty gray upperparts with broad white crescents. Gray neck and body, including rump and tail coverts. Dark secondaries and primaries with white trailing edge extending to p6-p8[6]. Tail dark with broad white tip, thicker than in third cycles. Head slaty gray with white peppering, with white concentrated around the base of the bill. White eye crescents. Bill orangish with greenish gray basally, black tipped. Legs liquorice black. Eyes dark brown to brown.

Head becomes white during prealternate molt, blending into neck. Bill turns bright red, with black tip reducing in size.

Citations

Howell, Steve N. G., Jon Dunn. "Peterson Reference Guides to Gulls of the Americas." The Peterson Reference Guide Series. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007, pp. 26, 105, 358-359.

"Heermann's Gull." All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024, www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Heermanns_Gull/id. Accessed 18 Jul. 2024.

A. Ruiz, Enrico, et al. "Demographic history of Heermann's Gull (Larus heermanni) from late Quaternary to present: Effects of past climate change in the Gulf of California." The Auk. Vol. 134, no. 2, 1 Apr. 2017, pp. 309. doi.org/10.1642/AUK-16-57.1.

Mellink, Eric. "History and Status of Colonies of Heermann's Gull in Mexico." Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. Vol. 24, No. 2, Aug. 2001, pp. 188. doi.org/10.2307/1522029.

Olsen, Malling Klaus. "Gulls of the World: A Photographic Guide." Princeton University Press, 2018, pp. 125.

Ayyash, Amar. "The Gull Guide: North America." Princeton University Press, 2024, pp. 146, 149-150.

Howell, Steve N. G., C. Wood. "First-Cycle Primary Moult in Heermann’s Gulls." Birders Journal. 75, 2004, pp. 40-43.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

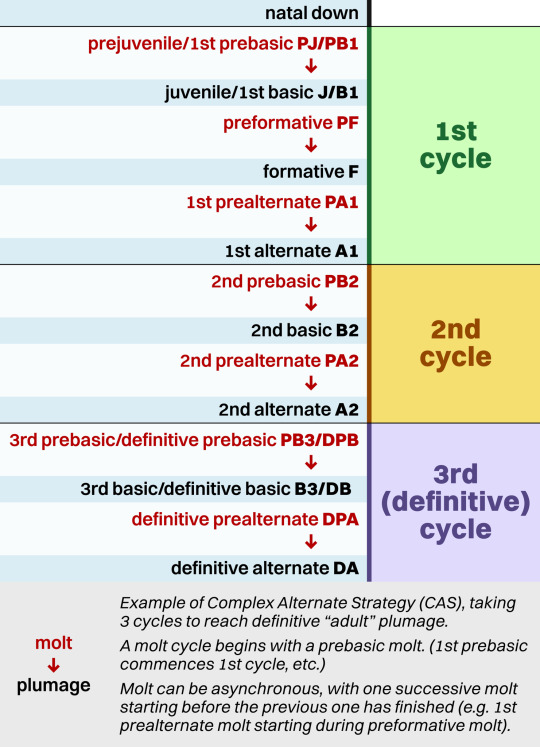

I made this little diagram to help visualize Humphrey-Parkes-Howell terminology.

It might seem daunting at first, and talking about moult in terms of cycles can feel detached from reality. However, once the initially steep learning curve is overcome, describing moult in terms of homologies helps untangle the confusion surrounding birds whose moult strategies do not fit neatly into Life Cycle terminology (e.g. neotropical birds that do not experience distinct seasons like in boreal regions.)

For those interested in learning the HP/HPH system, check out these links:

Moult terminology: envisioning an evolutionary approach

https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.02958

0 notes

Text

Differences Between Ring-billed and Short-billed Gulls

September 29, 2024

Misidentifications I see on the Metro Vancouver eBird somewhat frequently involve Short-billed and Ring-billed Gulls, especially juveniles and first cycles (juveniles that have begun the first pre-alternate/pre-breeding moult).

Adults are the easiest to separate.

Ring-billed Gull gets its name from the black band towards the end of the bill. At most, Short-billed Gull will have dark markings in a similar position, but never a complete ring. Sometimes the bill tip of some Short-bills is yellow, and the basal portion greenish yellow.

Adult Ring-billed Gull in breeding plumage. Note black band around outer bill, pale yellow eye.

Adult Short-billed Gull in non-breeding plumage, undergoing prebasic/post-breeding moult. Head is all white during breeding season, like Ring-billed Gull. Note dusky, speckled eye.

Also, Ring-billed is larger than Short-billed, has a lighter grey mantle (upper body) and pale yellow eyes instead of dusky/speckled.

In flight, Ring-billed has smaller wing mirrors on p10-p9 than Short-billed Gull (white patches near the top of the outer two wing feathers).

Ring-billed gull in prebasic/post-breeding moult. Note limited wing mirrors on outer primaries.

Short-billed gull in prebasic/post-breeding moult. Note extensive wing mirrors on outer primaries.

The juvenile plumages of both species are reliably identifiable as well.

Ring-billed is whiter overall, with contrastingly dark brown patterning on upper body, wings and behind the tail. Short-billed is grey-brown overall, bleaching whitish over winter.

Both species's bills start off dark, then become pink at the base. The dark tip of Ring-billed is more clearly demarcated.

#birding#birds#birdwatching#gulls#larus#bc#canada#larusdelawarensis#ringbilledgull#larusbrachyrhynchus#shortbilledgull

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juveniles

August 22, 2024

Juvenile California Gull

Now that most of the local Olympic Gulls are out of their nests, scattered along beaches, docks and alleyways, I think it would be a good time to talk about juvenile plumages. I would also like to briefly explore the types of moult that young birds undergo in early life, particularly in their first year.

Juvenile Plumage

Nestlings in most species begin replacing their natal down in the nest in a process called prejuvenile moult, which results in juvenile plumage.* Juvenile plumages (and subsequent immature plumages, like those of larger land birds and gulls) are fascinating, fine-tuned to give a young bird the best chance of survival. Thrushes like American Robins are speckled with dots and teardrop patterns to confuse a chasing predator, while the muted grey and brown colourations of Larus gulls act as camouflage. In fact, as for adult birds, juvenile plumages serve multiple and often conflicting functions (e.g. predator confusion vs camouflage), which find balance through natural and sexual selection.1

Fledgling Swainson's Thrush. Notice the buff teardrops on the upperparts and speckled chest.

Formative Plumage

There is also a wide variety of moult strategies for immature birds. In most cases, juvenile feathers have to grow quickly, being semi-functional by the time the bird has left the nest. Because of this, these feathers are of lower quality than adult feathers. Combined that with the fact that most species have a longer delay between prejuvenile (first prebasic) and second prebasic moult than subsequent moults, many species have supplemental moults to maintain feather quality.2 The preformative moult takes place after, or even before, the prejuvenile moult has completed, producing formative plumage. In many songbirds, and small gulls like Bonaparte's and Franklin's Gull, this moult is limited to body feathers and some coverts, though there is much variation.

First cycle Franklin's Gull. This individual has some grey feathers appearing on its upperparts, marking the start of the preformative moult.

Alternate Plumage

Larger gulls (Glaucous-winged Gull, Herring Gull, Ring-billed Gull, etc.) do not have a preformative moult.** Whereas the prebasic moult is usually complete (replacing body and flight feathers) and coincides with the nonbreeding season, the prealternate moult replaces less feathers. Alternate plumage--think of it as alternating with basic plumage annually--is completed around the breeding season for many species, and is often when you see birds at their most colourful. Birds that take multiple years to reach adulthood still undergo this prealternate "prebreeding" moult--it just looks a little messy. When my local Olympic Gull Juveniles start developing grey feathers on their backs, that is the prealternate moult in progress.

First cycle Ring-billed Gull beginning its prealternate moult (light grey on upperparts).

I know I am throwing a lot of jargon around--moults, cycles and bears, oh my! If anything, this is just me, a novice birder, trying to express my excitement about such misunderstood and under appreciated subjects as the plumages of juvenile and immature birds and the process of moult in general.

Until next time.

*I might confuse a few people writing about H-P terminology and the WRP system in Canadian English. Hopefully more Old World articles begin to be written using these standards, trading in Life Cycle terminology, which has an initially shallow learning curve, with that which better accounts for eclipse plumages in ducks and variation in moult duration in neotropical birds.3

**Preformative moults actually occur in most birds, according to Pyle. However, it is not appreciable enough in the larus gulls I come across. I need to look into this further.

References

Jenni, Lukas, and Raffael Winkler. “The Biology of Moult in Birds.” Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020, pp. 10.

Pyle, Peter. “Identification Guide to North American Birds.” Part 1, Second Edition, Slate Creek Press, California, 2022, pp 16.

Wolfe, Jared D, et al. “Ecological and evolutionary significance of molt in lowland Neotropical landbirds.” Ornithology, Volume 138, Issue 1, 2021. doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukaa073

#birding#birds#birdwatching#gulls#larus#bc#canada#glaucous-winged gull#larusglaucescens#larusoccidentalis#franklins gull#bonapartes gull#molt#moult#plumage

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Third cycle Heermann's Gull. What a treat to see in my neighbourhood.

(Vancouver BC, May 29 2024)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Adult California Gull.

(Vancouver BC, April 6 2024)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Second-third cycle Olympic Gull.

(Vancouver BC, April 26 2024)

#gulls#birds#larus#olympic gull#birdwatching#birding#glaucous-winged gull#western gull#larusoccidentalis x glaucescens#larusoccidentalis#larusglaucescens#vancouver bc#vancouver#bc#canada#bird photography#salish sea#seagull

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gulls

March 19, 2024

“I was mugged by a gang of seagulls” reads the title of a Tripadvisor review for Granville Island1. “When I came outdoors [a] gang of seagulls attacked me and stole part of my lunch.” Anyone who has eaten a meal outside of the Granville Island Public Market will understand this frustration. Seagulls watch like sentinels from rooftops, above benches and dining tables, on the lookout for a loose pizza slice; grey-coloured seagulls beg near sitting diners, screeching incessantly. Some seagulls patrol the skies above, while others choose to stay close to the ground, walking around on webbed-feet, waiting for loose food items and handouts. It would be easy to overlook these birds as a nuisance—rats with wings, to quote the pelican from Finding Nemo. They may be kleptoparasites, stealing food from other animals, including lunching humans and unsuspecting tourists. But seagulls are so much more than just ratbirds. In the Salish Sea region, they humble the proudest of birders trying to make an ID. (Is that light grey-mantled gull with darkish grey wingtips a Western x Glaucous-winged Gull hybrid or a darker Glaucous-winged Gull? Does the slightly smaller, petite head indicate hybridization with a Herring Gull, or is it a female of another species? Is its eye colour dark or pale? How about the colour of the orbital rings?) Their increasing reliance on urban breeding grounds (e.g. rooftops) serves as a litmus test for habitat degradation, and also gives researchers an opportunity to study how fauna adapt to urban living. How does the diet of an urban dwelling Glaucous-winged Gull Larus glaucescens differ from one that spends its time in more remote areas? Do urban seagulls lay more or less eggs than their counterparts? What is the survival rate of their young in to adulthood? Researchers have been hard at work answering these questions2. One recent study flew drones above buildings in Victoria to study nest sites of Glaucous-winged Gulls, a wonderful example of new technology opening up more avenues for scientific inquiry3.

Before going further, I need to address a misnomer. Gulls belong to a diverse group of birds in the family Laridae, from the circumpolar, all white Ivory Gull Pagophila eburnea, to the grey-bodied Lava Gull Leucophaeus fuliginosus and coal-black backed Olrog's Gull Larus atlanticus in South America. (Melanin—the pigment responsible for skin colour in humans—is what gives darker tones to feathers. It helps resist sun bleaching, which is why gull species's upper bodies trend towards darker tones closer to the equator4.) The Heermann's Gull Larus heermanni is a true pelagic (literally “ocean”) species, individuals spending their days hunting for fish, rarely going inland. Then there is the California Gull Larus californicus, which breeds inland of the Western United States; and the Ring-billed Gull Larus delewarensis, prolific in most of North America, but rarely straying beyond coastal waters5. This is why you will almost never hear birders refer to seagulls as such. Many gulls are generalists, found in urban centres, prairies, rivers and lakes, landfills, open oceans and coastlines. Calling them seagulls would be a disservice to their enterprising nature, breeding on every continent, including on the fringes of Antartica. Many of these species have adapted to living in rapidly expanding human-made habits. We can conflate this success with the annoyance conjured up in many people's minds when they think of these birds: Their pervasiveness; their loud squawking; the mess they make with their guano; and their proclivity towards thievery. Perhaps the things humans find so irritating about gulls are actually what we hold most in common. But I digress. No birder or ornithologist worth their salt is going to call you out for saying seagull instead of gull. (If they do, they will bring it up benignly.) Gulls as a label in itself is taxonomically ambiguous, pertaining to several genera within the Laridae family while excluding terns, skimmers and noddies. Instead of splitting feathers over vernacular, try learning about local gulls in your neighbourhood (if you have any.) Download an app like Merlin or Audubon for quick reference if you stumble upon an interesting bird. Your local gull species may not have the vocal acumen of a Song Sparrow Melospiza melodia, nor the fantastically coloured plumage of a Wood Duck Aix Sponsa. For me at least, I find tremendous enjoyment in watching a second winter Olympic Gull walk past me, a collage of grey and brown and white; or seeing a first winter individual staring at me with those deep and dusky eyes, its first grey scapulars developing, like ash on a dirt road. Gulls are full of personality. I observe them trying to snatch fish from cormorants; pulling up worms from park grass; standing on volleyball pegs and tidal rocks, heads tucked in behind their backs and bodies rotating side to side as if to lull themselves asleep. Even the seemingly normal, mundane, sometimes irritating aspects of life can offer up wonders if you are patient. Gulls or otherwise.

References:

“I Was Mugged by a Gang of Seagulls – Granville Island, Vancouver Traveller Reviews – Tripadvisor.” Tripadvisor, 2011, www.tripadvisor.ca/ShowUserReviews-g154943-d156255-r120159573-GranvilleIsland-VancouverBritish_Columbia.html.

Edward Kroc. “Reproductive Ecology of Urban-Nesting Glaucous-Winged Gulls Larus glaucescens in Vancouver, BC, Canada.” Marine Ornithology, vol. 46, 2018, pp. 155–16.

Louise K. Blight, Douglas F. Bertram, Edward Kroc. “Evaluating UAV-based techniques to census an urban-nesting gull population on Canada’s Pacific coast.” Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems, vol. 7(4), 2019, pp. 312-324. https://doi.org/10.1139/juvs-2019-0005

Steve N.G. Howel, Jon Dunn. “Peterson Reference Guides to Gulls of the Americas.” Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007, p. 25.

Birds of the World, https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow

#gulls#gull#seagulls#seagull#bird#birds#birdwatching#birding#vancouver#vancouver bc#salish sea#bc#british columbia#canada#larus#larusglaucescens#glaucous-winged gull#larusoccidentalis#western gull#larusoccidentalis x glaucescens#olympic gull

4 notes

·

View notes