everything4everyone

12 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Seeing the world anew – seeing new worlds

‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle’ – Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto.

‘Who would be free themselves must strike the blow?’ – Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage – and frequently quoted by Frederick Douglass

‘We are not to be saved by the captain… but by the crew’ – Frederick Douglass

‘It is more difficult to honour the memory of the anonymous than it is to honour the memory of the famous’ – Walter Benjamin

In 1964, Mario Tronti famously performed a ‘Copernican inversion’ of orthodox Marxist theory:

We too have worked with a concept that puts capitalist development first, and workers second. This is a mistake. And now we have to turn the problem on its head, reverse the polarity, and start again from the beginning: and the beginning is the class struggle of the working class. At the level of socially developed capital, capitalist development becomes subordinated to working class struggles; it follows behind them, and they set the pace to which the political mechanisms of capital’s own reproduction must be tuned.

Describing this as an ‘inversion of the class perspective’, Harry Cleaver explains. Workers struggle; human beings resist domination. And it is these struggles, this resistance, that forces capital – and its managers – to develop more sophisticated modes of subordinating people to its logics. Without our struggle, there would be no development.

A good example of this – that Cleaver unpacks – is the movement from capital’s strategy of ‘absolute surplus value’ to ‘relative surplus value’ production, which Marx explores in parts III, IV and V of the first volume of Capital. Absolute surplus value – sometimes described as ‘extensive exploitation’ – is generated by extending the length of the working day, making workers work longer: more hours per day, more days per year. Relative surplus value – ‘intensive exploitation’ – is produced when workers work more intensively, producing more commodities, in a given number of hours. This is nearly always achieved by the introduction of new machinery, which increases productivity. Of course, capitalists invest in productivity-enhancing machines because they believe this will be profitable. This is obvious. Cleaver’s point – and Tronti’s – is that capitalists make such investments in so-called fixed capital because they really have little choice but to do so. They are responding to workers’ struggles to limit the length of the working day and to a much more generalised refusal of work. Machines don’t get tired, they don’t soldier, they don’t go on strike. New machinery that increases productivity and output is one important aspect of capitalist development. But it doesn’t stop there. Complex machines require more skilled, more reliable workers to operate them – because more complex machines are typically more vulnerable to sabotage. And so on.

Tronti’s ‘workerism’ was focused on male factory workers struggling in and against Italy’s rapid post-WWII industrialisation. But the insight that capitalist development is driven by struggle and resistance has also been advanced by feminists studying women’s struggles, post-colonial scholars recovering the history of slave revolts and other resistance by colonial subjects, and ‘from-below’ historians and anthropologists uncovering the practices of peasants, campesinos and commoners. It’s the perspective captured in Larkin’s maxim that his friend and comrade James Connolly put on the masthead of the Workers’ Republic, the paper he founded in 1898: ‘The great only appear great because we are on our knees. Let us rise!’ It’s the perspective that W.E.B. Du Bois channels in his ‘general strike’ thesis. Du Bois’s argument is that slaves’ class consciousness and their massive and multi-faceted revolt changed the nature of the United States’ civil war, from a war to save the Union into a war to end slavery – a thus a war that forced capitalism onto a new trajectory.

There are two points to make about this perspective. First, it goes against everything we have been taught, almost everything we are exposed to, day in day out. In Stephen Spielberg’s film Lincoln, for example, Abraham Lincoln is shown as the driving moral force responsible for ending slavery – reinforcing both the popular reputation of the 16th president of the United States and the ‘great man of history’ understanding of social change. We celebrate the accomplishments and inventions of other great men – James Watt, James Hargreaves, Charles Babbage – but forget the context in which they were working and struggling. We are rarely taught that the problems they set out to solve were as much social as ‘technical’. Marx: ‘It would be possible to write a whole history of the inventions made since 1830 for the sole purpose of providing capital with weapons against working class revolt.’ (The best such history of these inventions is this one – but it’s not part of any national curriculum that I’m aware of.) When commoners or proletarians appear in these stories, they are usually passive and they are usually victims – people we might pity.

But consider Silvia Federici’s accounts of witches and witch-hunting. Reading her work, we can never forget that those thousands of women, and a smaller number of men, who were persecuted as ‘witches’ were victims – as were countless others who were thereby intimidated and pacified. They were victims because of their persecution as ‘witches’ and, more broadly, because it was women, especially older women, who were typically more impoverished and socially excluded by the brutal dislocations caused by the development of capitalism. But what distinguishes Federici’s work from other histories of ‘witchcraft’ and witch-hunts is that she points out that for these women to have been so victimised and so persecuted, they must first have inspired fear amongst social elites – clergy, landlords and well-to-do peasants who gained economically from the processes of enclosure that were dispossessing the majority. These women were a threat! Victims, yes, but not passive; they were also active subjects of history. Silvia Federici opens up the possibility that witch-hunting was widespread – in North America and Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in parts of Africa and Asia today – not because women were weak, but because they were, and are, powerful.

Second, when we are first exposed to this perspective it can be quite jolting. Not only does it stand in such contrast to the ‘great man’ histories and to the dominant narrative of most oppositional thought. This way of seeing the world, this mode of thinking – both as methodology and as ontology – opens up a possibility that is initially troubling. Perhaps we are to blame. For the ‘productivity slowdown’ of the 1970s. For the rise in mechanisation and automation – think ‘jobless recovery’ – and the ‘outsourcing’ of jobs. For the expansion of lethal nuclear power plants. For the ‘destruction of the family’, fast food and the TV dinner. For the return of low-waged domestic labour. For the catastrophically unsustainable burning of fossil fuels. Perhaps we have brought these misfortunes on ourselves – just as the misogynist blames the assaulted woman for dressing or behaving ‘provocatively’.

In a sense, this is true. Take George Caffentzis’s extensive scholarship into the political economy of energy – probably the second most important commodity or set of commodities – after that ‘special commodity’, labour-power itself. (George’s work directly updates Marx’s own writing on the introduction of machines in Capital.) In one strikingly simple yet illuminating paper, he estimates the thermodynamic energy produced annually by the burning of oil vis-à-vis the energy that, hypothetically, could be produced in a year by human labourers – creating what we might think of as an estimate of the ‘calorific composition of capital’. His argument here is that the astonishing growth in the work done by fossil fuels – first coal and then oil – over the past few centuries should be understood as capital’s response to workers’ refusal of work.

To attack the resistant power of workers, capital creates whole universes that are valueless in themselves. The 360 billion human work-years of energy derived from oil are directed at exploiting substantially less than 6 billion work-years of energy embedded in resistant human labor!

Another kaleidoscopic side of this history are the myriad struggles of energy workers themselves – over wages, working conditions and the uses to which the product of their labour is put – along with those of ‘environmentalists’ – from campaigners against ‘smog’, to anti-nuke protesters, to ‘keep it in the ground’ activists. Taken together, these struggles have shaped profoundly capitalism and world we now inhabit.

‘Blame’ is not quite the right word here. But we should nevertheless recognise – and embrace – our responsibility. For our responsibility – overawing as it might be at times – is our power and our liberation. In the appalling fucked-up-ness of a world in which violence against women – as well as against LGBT people – is so widespread, a kernel that should give us succour is that a woman’s – or a gender-queer person’s – power to provoke is exactly that – a power, a power that is indicative of these subjects’ potential to transform gender relations, sexual relations and – more broadly – social relations. In the appalling fucked-up-ness of a world full of so many horrors and so many crises, we must take succour in the knowledge that we created this world – and we created its crises.

We are the crisis of capital and proud of it. Enough of saying that the capitalists are to blame for the crisis! The very notion is not only absurd but dangerous. It constitutes us as victims.

This is why human history is a drama and not a tragedy. We should never forget Marx’s famous observation in The Eighteenth Brumaire: ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.’ But, in fact, we should reverse it in order to invert its emphasis: we rarely do so in circumstances of our own choosing, but nevertheless we make our own history.

This is not really a new way of seeing. But this lens – the lens through which we see change coming from below, the lens through which we can both see the world anew and see new worlds – must constantly be polished and refined. It keeps getting fogged up by the hot air of dominant narratives, dominant histories – not only perpetuated by politicians and the BBC, but by most Marxists, social movement activists and self-styled alternative and radical media. Each political generation must learn to use it, to see in this way.

Take the furore over Britain’s imminent exit from the EU. I see Leftists dolefully sharing predictions of the likely damage to trade and ‘the economy’ following Brexit – just as some of those Leftists approvingly shared reports in which establishment economists or the International Monetary Fund have made approving noises about the prospects for growth and ‘the economy’ under a Corbyn-and-McDonnell-led Labour government. Only two decades ago there was a hundreds-of-thousands-strong movement against free trade. This movement was more-or-less successful – in its immediate objectives at least: we forced the abandonment of every ambitious free-trade treaty and discredited the World Trade Organisation, along with the IMF and the World Bank. A shocking victory. It’s true we failed to foment wider social revolution – and it’s possible these successes of the counter-globalisation movement helped pave the way for the likes of Trump and rising xenophobia more generally. But we should nevertheless remember – and celebrate – these victories, even as we grieve for their lost potential. These victories are expressions of our power. We – and not Trump or anyone else – buried the ‘liberal international order’!

I haven’t been able to trace the source of the final quote. I found it jotted down in a notebook, maybe from years ago. It sounds like Subcommandante Marcos, one of the most important critical thinkers of the 20th century and beyond. But it could be Franz Fanon, John Holloway or Ursula LeGuin (‘maybe the Odonian manifesto in The Dispossessed?’). But it’s appropriate that no one seems sure. As one comrade commented: ‘it’s the core of all magic’ and, most importantly, ‘it’s from everywhere!’

‘We make this world. We can unmake it and make others.’

0 notes

Photo

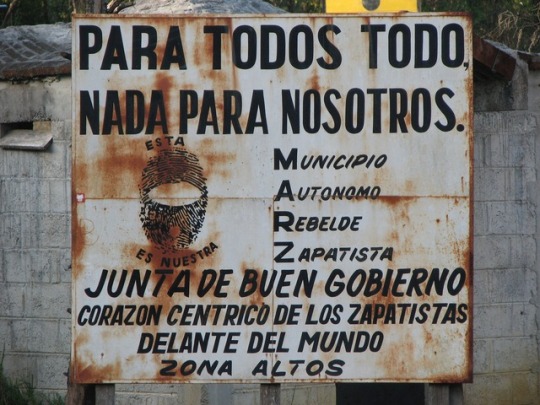

Through the looking class

When I look in the mirror, I see more than a simple reflection of my outward appearance. Most of the time I see a ‘me’ that is more ‘me’ than yesterday. This is partly an effect of growing old. A few months back I was driving home when I stopped to let an old man and young woman cross the road. He was walking with a slight stoop, his face was pinched and his clothes had clearly seen better days; it was only when he had crossed that I recognised him as one of my best friends. He was on the wrong side of town at the wrong time of day but it was still a shock to realise that this battered old man was only 12 months my senior. Fuck! Is that what I look like?

But it’s more than just old age that stares back at me. There’s been a steady accretion of experiences, postures, and events which all combine to make me more ‘me’ than ever. Thirty years ago the ‘me’ that stared back from the mirror was more unformed. Less substantial maybe but also open, unshaped. A face that was (literally) not yet scarred. A face that was to-come. Today the lines on my face tell a story of where I’ve been, of who I’ve been, of who I’ve become. These calcifying layers put me in mind of a 1950s B-movie where the protagonist is gradually sheathed in some kind of hard carapace until the only thing moving is an eye which grimly blinks out an S-O-S like a human lighthouse. Actually I think I’m combining several different cinematic tropes here but you get the picture: as I’ve become more ‘me’, the conditions of possibility have necessarily become more constrained.

There’s a link here, I think, to one of the problems of political organisation: how do you grow without becoming more like yourself? Of course this isn’t necessarily a problem if you see revolution as a matter of aggregation, of marshalling our forces until we have the strength to overthrow our rulers. That’s a typically Leninist top-down view, where the aim is precisely to grow, to become more like yourself, changing only in volume. Qualitative change (revolution) occurs through quantitative growth. We are nothing but must be everything and the way to do that is to build the party, recruit members, flex your muscles.

To be fair, this sort of approach makes lots of sense even if you’re not a Leninist. Every group has to reach some sort of critical mass in order to do anything, and constructing a group identity is an inevitable part of this. It also defines a collectivity, ensuring that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. But there’s a problem. Once the identity assumes a certain shape, it tends to become meaningful to a limited number of people; in the worst case it might only be visible to a tiny minority. In some cases this might be fine—a Cheese and Wine Appreciation Society, for instance, doesn’t have to care about vegan teetotallers. But if you want to transform the world, and you see real change only coming from below, organisations with a skewed membership are problematic because they tend to end up with a skewed (or at least partial) outlook. If all you see around you are fresh-faced twenty-somethings, then you can easily end up thinking that’s all the world is composed of. It’s like the classic London bubble where “politics” amounts to talking heads prattling on to other talking heads about events in Westminster.

One way to deal with this is to think about the make-up of a group, the way that’s it weighted in favour of certain types of people (and therefore more or less attractive to others). But that runs the risk of collapsing back into a very static idea of what constitutes identity. It might be more useful to come at it from the other direction, by taking seriously (Groucho) Marx’s claim that “I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member.” The collectivity of an organisation offers us a space to become more than the sum of our parts. In other words, part of the reason I want to join a club is precisely in order not to be me.

“I am nothing but I must be everything.” That’s definitely one strand of revolutionary politics. On the evening of Rosa Luxemburg’s murder, she wrote: “Your ‘order’ is built on sand. Tomorrow the revolution will already ‘raise itself with a rattle’ and announce with fanfare, to your terror: I was, I am, I shall be!” This is class as something which just “is”, and as something which has a historic role. Back in the late 1980s/early 1990s Class War operated mostly with just such an approach. But there’s an equally important strand which looks at class as process, as something which happens. In the Preface to his seminal Making of the English Working Class E P Thompson is crystal-clear: “I do not see class as a ‘structure’ nor even as a ‘category’ but as something which in fact happens.” Class, in this sense, is also something which is always to-come. If we think about political organisations in this way, then we can flip Marx’s assertion and start to ask different questions: rather than becoming everything, how do we (as an organisation) become nothing? How do we come to the end of ourselves as we are?

In politics, demands go from one body to another. “We” demand more pay, better resources, greater freedom. “They” demand tighter border controls, more armed police on the streets etc. When we make those demands, we often reinforce our identity as a social force. “We” become ever more workers, social democrats, trade unionists, activists etc. But “everything for everyone” is a very different sort of demand because it doesn’t go in any specific direction. It isn’t to anyone. And it isn’t from anyone. In that respect, it might be one way to step through the mirror and address the perennial paradox of revolutionary transformation, summed up brilliantly by Kathi Weeks:

Can we want, and are we willing to create, a new world that would no longer be “our” world, a social form that would not produce subjects like us?

0 notes

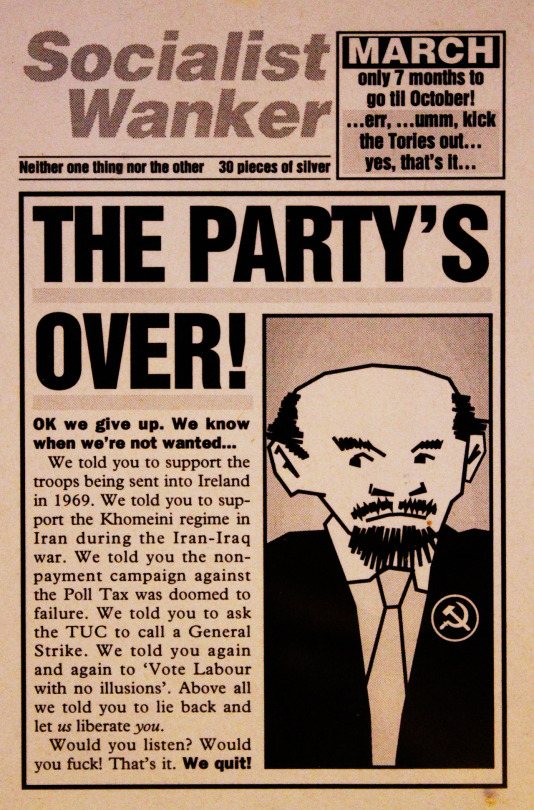

Photo

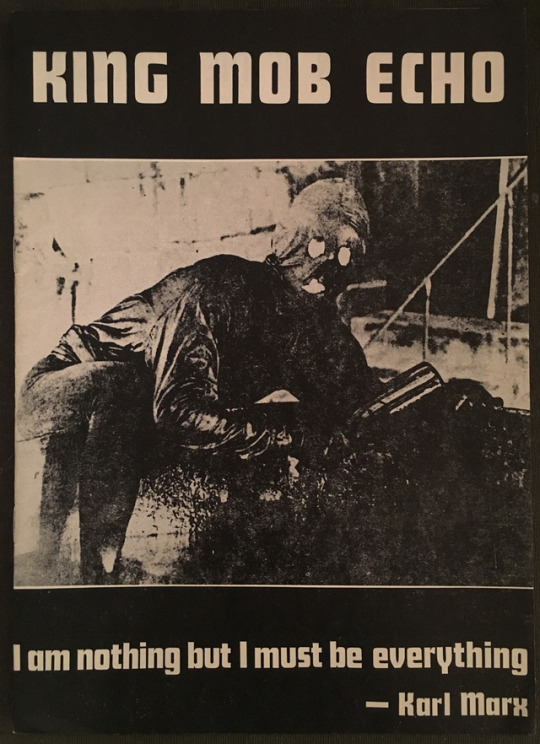

The beaten generation?

I’ve just finished reading King Mob: A Critical Hidden History so it seems a good excuse to post this cover from the first issue of King Mob Echo. Plus it features that brilliant Marx quote.

I’ve always been a fan of the Wise brothers (because of their BM Bis/Blob/Combustion work) but while King Mob has some of their usual sparkle, it turned out to be a fairly depressing read. Like a lot of writing about the late 1960s/early 1970s it’s a tale of comedown writ very fucking large. As that huge wave of global struggles ended, the social movements it had thrown up splintered and fell apart. In the UK, as the spirit of collectivity and experimental daring started to disintegrate, people looked to prepare individual escape routes. As Enzo Traverso puts it, “the concrete utopias of collective emancipation turned into individualized drives for the inexhaustible consumption of commodities.” Practically this meant people turned to drugs; cracked up; dabbled in mysticism; got tangled up in petty (and not so petty) crime; or more prosaically, got their heads down and found ways to survive. Of course those who came from money found the comedown a little easier to handle—many fled the movement to become good capitalists, changing their votes along with their overcoats—but the fragmentation was real and left lasting scars on all those who lived through it.

The left-wing melancholy which Traverso writes about pervades much of King Mob. And that’s hardly surprising when you consider what the Wise brothers and their comrades lived through. As Traverso makes clear, melancholy isn’t a choice or a strategic decision: it’s what the survivors are left with after the shipwreck. The key thing—and I know I’m banging the same old drum here—is how you work through those experiences. How do we deal with the history of defeated revolutions, with the apparent eclipse of those utopian impulses? Traverso sees melancholy in a more positive way than some:

If we abandon the Freudian model and “depathologize” melancholy, we could see it as a necessary premise of a mourning process, a step that precedes and allows mourning instead of paralyzing it and thus helps the subject to become active again. In other words, melancholy could be seen as an enabling process in which, according to Judith Butler’s lexicon, the subject experiences “a withdrawal or retraction from speech that makes speech possible.”

A beaten generation? Well, maybe. But it’s also crucial to remember that the defeats of the last fifty years (just like the defeats of the last 300 years) have not been final. How could they be? It might feel like a history of battles fought and lost, but the class war against domination is not over. We are nothing but we will become everything…

0 notes

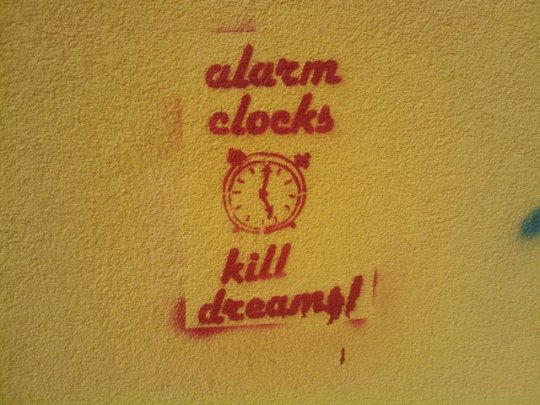

Photo

This or that?

The above graffiti* appeared on the streets of France during the recent gilets jaunes protests. Roughly translated as “Give us cash while we wait for communism”, it’s perhaps another way to re-pose Luxemburg’s question: Reform or revolution? Inside or against? This or that?

Like most people, I’ve got a complicated relation to reformism, neatly encapsulated by my introduction to political thinking. I was working as a waitress in a cocktail ba… no, hang on, I was working in the packing department of a pneumatics supplier when two fellow workers moved from talking about punk to talking about politics. “Are you a lefty, then?” said one. “Umm, dunno…” I muttered, not really sure what they were on about. I mean, I’d got a post-punk sensibility (this was 1981) but I was pretty wet behind the ears. “Well, you should get hold of Tony Benn’s Arguments for Socialism and The Communist Manifesto…” And there you have it: a manifesto for radical social democracy from a bona fide aristocrat set alongside a call for global proletarian revolution. Give us cash while we wait for communism indeed…

The standard defence of reformist politics is that utopian impulses are all very well but we have to operate in the here and now. If that means small, incremental steps for social change using existing infrastructures, then so be it. Whether it’s better working conditions, improved housing, new transport policy initiatives, it’s indisputable that something is better than nothing. Sure, something is better than nothing. I’m not daft. But is that the only choice? Will those small somethings add up over time to everything? Will a series of piecemeal changes open up the space for a totalising critique? Put another way, how can we square this approach with the revolutionary daring which proclaims “I am nothing but I must be everything”?

When Jeremy Corbyn swept to victory as leader of the Labour Party in 2015 and was then re-elected with an increased mandate the following year, it was placed alongside victories for the likes of Podemos and Barcelona en Comú in Spain and Bernie Sanders in the US: a British version of the worldwide “electoral turn”, a wave of progressive politics which would at last offer an alternative to a corrupt and zombified neoliberalism. Comrades who had been active for years in extra-parliamentary struggles enthusiastically signed up to the programme and did significant legwork in the 2017 general election. Labour’s defeat on the night (by a smaller margin than predicted) was again taken as a sign that “something is really happening…”.

But what exactly is that “something”? Two points spring to mind.

First, there really is nothing new under the sun. Over the past hundred years there have been countless decent revolutionaries in the UK who have dabbled with the parliamentary road to socialism. My two co-workers were both part of the hugely influential Bennite left in the early 1980s; I joined in 1983 and canvassed in that year’s election. Many of today’s Corbynites refer back to that era to validate their own journey, as if Corbyn’s ascension to power is the culmination of a long march through the institutions. But that’s far too simplistic. In fact, Corbyn self-evidently did not ride to power on the back of a powerful extra-parliamentary social movement. Instead his victory was a surprise to almost everyone involved. More importantly, as some have pointed out, those periodic electoral turns tend to happen not from positions of strength but at the arse-end of social movements, as activists seek some form of shelter from collapse, fragmentation and burnout.

Second, there is an almost inescapable logic to electoral politics which is all about leadership, Westminster and triangulation towards the (perceived) media. The Labour Party has to act quickly to appease the City, Daily Mail journalists, ‘public opinion’ in the traditional Labour heartlands etc etc. So we get the infamous calls for tighter border controls and more police on the streets, while the shadow Chancellor promises a ‘competitive’ economy and boasts about ‘productive’ meetings with asset fund managers. The revolutionary project gets reconceptualised as a strategy for gaining political power – or more precisely public office. Pragmatism is the order of the day: cash not communism. In this strategy, Left celebrities, intellectuals and academics are disproportionately represented – and without wider social movements to rein them in, all sorts of nonsense gets spewed out… Apparently we are witnessing “a social movement poised to take state power”. The level of hubris on display is quite staggering.

None of this is to say that revolutionaries shouldn’t join the Labour Party (as if I’m in a position to judge…), but we need a little bit of honesty here. I totally get the frustration with horizontalism, but we have to start by thinking through the exhaustion of that cycle of struggles which erupted after 2007–8, not to mention the defeats of the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s etc. It’s hardly surprising that the last 40 years have left us shattered, marginalised and occasionally desperate. So there’s no doubt that a Corbyn-led administration would offer a much better place to live for most of us, while also creating a potential space for more radical, transformative politics. But when I’ve talked to a couple of comrades swept up in Corbynmania, they’ve gone much further, explaining that the key attraction for them is “actual social change” – as if voting Labour (and getting bussed into other cities to encourage others to vote Labour) is entirely unproblematic; and as if refusing to join up means you’re not serious about “actual social change”. It’s disingenuous, to say the least.

Similarly I keep hearing people trot out the line that the Labour Party is now “the only game in town”. They state it as scientific fact rather than a political claim (one that’s deeply contested). It’s as if the whole trajectory of neoliberal politics from the late 1970s onwards is just a matter of having the wrong leader or the wrong ideas – it’s nothing to do with class composition at all. And I know it’s only a phrase, but I’m starting to hate the use of the word “game”. It adds to the whole notion of politics as a career choice for intellectuals, a job for specialists. A bunch of London postgrads joking on stage with John McDonnell or dancing with Clive Lewis is “a game”. I’m reminded of Adrian Mitchell’s comment that “Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people.” It’s the same with “politics”.

Reform or revolution aren’t the actual choices on offer. We don’t have to choose between this or that. The old Solidarity rule of thumb is useful here, as ever:

Meaningful action, for revolutionaries, is whatever increases the confidence the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the equalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the masses and whatever assists in their demystification. Sterile and harmful action is whatever reinforces the passivity of the masses, their apathy, their cynicism, their differentiation through hierarchy, their alienation, their reliance on others to do things for them and the degree to which they can therefore be manipulated by others – even by those allegedly acting on their behalf.

* Yeh, yeh, I know this isn’t really a random slogan thrown up in the heat of battle but it’s a pretty cool photo. And I can dream, can’t I?

0 notes

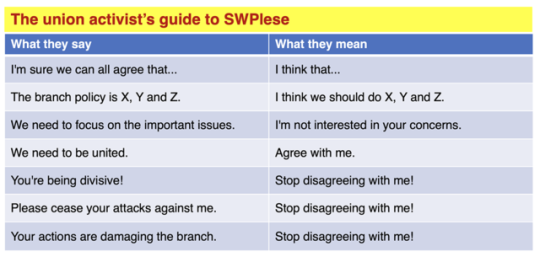

Photo

A letter to the Socialist Worker Party types at the heart of my union branch

Dear C and P

I was excited when you arrived and got involved in the branch. You captured key positions – I say ‘captured’, probably you just volunteered for them when incumbents had had enough – and the character of the branch seemed to change overnight. Where before branch officials appeared acquiescent and eager to maintain cordial relations with management, you were belligerent with bosses and prepared to fight. I give you credit for this. And I give you credit for getting me involved too. (Though as a comrade remarked later, you preferred for me to be inside the tent pissing out, rather than outside and pissing in.) I knew you were SWP members – or possibly you’d allowed your membership to lapse after the Comrade Delta events – but I was optimistic we could still work together.

I can’t fault your dedication and your discipline. But you never seem very interested in strategic thinking – and this was obvious from the beginning. Militancy of course! But always a reluctance to discuss what this might actually mean. How exactly might we strike against our employer? And beyond better ‘pay and conditions’, what might our workplace look like? Under your leadership of the branch there never seems to be enough time or space to talk about these questions; in fact such questions are usually shunted to the agenda-end and then timed out.

Other problems became apparent later. If I or others express disagreement with you, you do what you can to neutralise and shut down that dissent. First you ignore it. Next might come an appeal to your own ‘experience’ – though actually, your ‘experience’, like that of all of us on the Left for the past four decades, has mostly been of defeat. Or you might instead cite union or branch ‘policy’ – when in fact no such ‘policy’ has ever been discussed, let alone agreed. Or you might allude to what is ‘expected’ – when such ‘expectations’ only ever mean what you would like to happen. If none of those things do the trick, then come the accusations of being ‘divisive’, of ‘damaging’ the union. Even of making personal attacks against you. (When, of course, the reverse is usually the case: you are past masters of the personal attack.) A final resort is the threat to use bosses against those who’ve refused to submit to your ‘discipline’. Let me repeat that. Although this happened only once, once is enough: on that one occasion you threatened to report me to managers if I did not do as you wanted. For shame!

I wonder if you ever ask yourselves what your legacy will be, how people will remember you. I have spoken to once-active comrades who withdrew because of your hectoring and your incessant demands. I have spoken to comrades who might have become more active if it weren’t for your patronising behaviour. I asked someone who used to work with you elsewhere if they’d ever encountered you. This was the response: “I once arrived at a branch meeting a few minutes early. P was there with one of his SWP comrades. ‘Sorry’, he said, ‘we’re having a meeting. Can you wait outside?’” Is that really how you want to be remembered?

I wonder why you do it. Why the deceit, why the hubris, why the bullying? At first I wondered if you thought I was stupid. Or perhaps you are. Have you never realised that I have been involved in anti-capitalist politics for more than three decades? Perhaps you are stupid. But it’s more than that. You simply can’t help yourselves. You’re like the scorpion of the fable with the frog. It’s in your nature. If you get the chance, you will sting and kill the very struggle that carries you.

I doubt you can change your nature – which would be revealing in itself – ‘revolutionaries’ who want to change the world but who are incapable of changing themselves! You will no doubt continue... stinging the struggle. But so will I. Remember I have been an anti-capitalist militant for 30+ years! And I thank you. You have reminded me that my struggle is a struggle against all the bosses – not only the employers, but the bosses and would-be bosses of the Left.

Yours

X

0 notes

Photo

Falling into fancy fragments

I went to see Viv Albertine speak a few weeks ago and a few things have been going round my head ever since.

First, there was the slightly surreal experience of paying a gig price to hear a punk icon give a talk in a music venue. I’m not saying it’s a bad thing (far from it) but it was a bit jarring. The room was packed, with all the hardcore fans down the front, in the (seated) moshpit. And of course it was a predominantly aging audience, people like myself. Again, that’s no bad thing but it felt odd to be in such a sedate atmosphere, especially when a few weeks earlier I’d been to see the Mekons whose original 1977 line-up kicked and screamed as if lives—theirs and ours—still depended on it. As if music mattered. Just to underline the point, they opened the set with a denunciation of capitalism before launching into ‘32 Weeks’

So I was struck by something Viv said in response to a question about whether she still listened to music. I’m paraphrasing here but the gist of her reply was that, for her, music had been a tool, a means of escape. The Slits had set out to deconstruct music, to break it down and tear it apart on the way to creating a different sort of world. So now it’s just too painful to switch on the radio and hear some clunking, predictable 4/4 rock’n’roll, as if the events of the late 1970s had never happened.

Of course, every generation sees the music that soundtracked its coming-of-age as uniquely powerful. Like a cup of tea, nothing is ever quite as good as it was the first time round. But I think there’s also something more going on. Mark Fisher put it well when writing about post-punk:

Post-punk was one of the spectres that loomed over the past decade [2000–2010]. Its history was extensively catalogued in Simon Reynolds’s book Rip It Up and Start Again; the music was pastiched by lumpen plodders such as Franz Ferdinand and Kaiser Chiefs, and served up again by originals such as Gang of Four, Magazine and Scritti [Politti], all of which reformed. The return of the post-punk sound had a double effect. At one level, it constituted the music’s final defeat—if conditions were such that these groups could come back, 30 years after the fact, and not even sound particularly out of date, then post-punk’s scorched-earth injunction that music should constantly reinvent itself must be as dead as its hopes for a revivified politics. Yet even the most degraded simulations of post-punk style carry with them a certain spectral residue, a demand—which these simulacra themselves betray—that music be more than consolation, convalescence or divertissement.

Viv Albertine was similarly unequivocal on this. Music in the late 1970s was far more than consolation, convalescence or divertissement. It was a way out. But after its “final defeat”, it was a broken tool, good for nothing.

Viv has now found success as an artist in her own right, gaining critical acclaim for her brilliant 2014 memoir, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. When she spoke in Leeds, she made much of the fact that she doesn’t have to answer to anyone: no family, no partner, no wider entity. She acknowledged that in some respects this gives her a privileged position, but it’s one that enables her to tell it like it is, regardless of cost. What we get with her is one woman’s voice. She spoke a lot about authenticity, about the artist’s struggle for truth.

It’s difficult to write this, but I can’t help thinking how much this also represents a ‘defeat’. The Slits were a fairly chaotic collective operating in a hugely creative environment. Punk and post-punk might have started from a point of discontent, frustration and anger but they were also massively experimental. They broke down the distinction between the ‘popular’ and the ‘avant-garde’, but they also collapsed the distinction between the band and the audience. In that sense, I don’t think The Slits or The Mekons or anyone else were trying to express ‘the truth’; they were just trying to work out how the fuck to escape this world. They were tapping into a deeper desire, one that went way beyond music (or clothes, or boys). As Matthew Worley puts it, “To be that what is not lay at the heart of the impulse to which punk gave (multiple) expression.” We’ve gone from a scream to a whisper.

Mark Fisher again:

At the end of history, the impasses of politics are perfectly reflected by the impasses in popular music. As political struggle gave way to petty squabbles over who is to administrate capitalism, so innovation in popular music has been supplanted by retrospection; in both cases, the exorbitant ambition to change the world has devolved into a pragmatism and careerism. A certain kind of depressive “wisdom” predominates … The world has been turned the right way up again. The emperor is on his feet, power and privilege are restored, and any periods when they were toppled seem like ludic episodes: fragile, half-forgotten dreams that have withered in the unforgiving striplights of neoliberalism’s shopping mall.

To be clear, this isn’t about ‘careerism’ or ‘selling out’ or ‘going straight’. This is about how we begin to deal with the experience of collective defeat. How do we politicise it so that those struggles are not lost? How do we talk about it so that it’s no longer privatised, about the actions of this or that individual?

Or as Devoto intones on Spiral Scratch:

I wander loaded as a crowd – a nowhere wolf of pain Living next to nothing – my nevermind remains

0 notes

Photo

The dull compulsion of economic relations

"It's eight o'clock in the morning. When you come out it will be dark. The sun will not shine for you today." —La classe operaia va in paradiso (The Working Class Goes to Heaven).

0 notes

Photo

The days are long but the years are short…

I’ve been meaning to write some notes about work for a while now but… well… work keeps getting in the way. Weekends come round fast but they’re over too soon, and then it’s back to work. Rinse and repeat. A life lived out in fits and starts to a rhythm of resentment. It’s not just me. It’s a sensation familiar to anyone who’s ever been caught up in waged work. But perhaps I’ve been feeling it more acutely of late, probably as a consequence of getting older, thinking more about mortality as I close on the finishing line (don’t even get me started on pensions).

Remember when computers were going to herald an age of leisure? Yet as everyone knows in their bones, we spend more hours working now than ever. It’s easy to think of capitalism as an economic system built around the need to generate profit, but actually it’s more than that. Capitalism is a mode of production that controls and dominates human beings by putting us to work – whether that work is waged or unwaged, ‘free’ or forced. To paraphrase the opening line of Capital, the wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails appears as an “immense collection of jobs”. Capital is a beast that must be fed; or perhaps we can flip that on its head and think of human beings as the beasts whose desire for freedom must be tamed, controlled, channelled or suppressed.

But if work is the problem, it’s still incredibly hard to imagine a world without work. And that’s partly… well… because of work. It structures our lives, it structures our bodies, it structures who we are. And it stunts our imagination. Years ago I remember a meeting around climate change where a few of us were trying to argue that the refusal of work should be put at the heart of the discussion. There was resistance, with some arguing quite passionately that the work they did in their everyday jobs was actually quite socially useful. And there’s the problem. The idea of ‘work’ conflates a whole bundle of things: there’s work, labour, meaningful human activity, and the stuff that we need to do to survive. It’s not even that these are separate activities: my average 9-to-5 of wage-labour involves all four. And that’s no accident.

The ceaseless imposition of work isn't just about forcing people into wage-labour force by driving them off the land and into cities. It’s not just about making people in jobs work longer and harder. It’s also about the way that capital tries to squash all human activity into something that follows a pattern set by wage-labour. ‘Leisure’ is a perfect example. On the face of it, it’s about time spent away from the constraints of wage-labour. Whether you work as a teacher, as a nurse, or as a builder, leisure is set up to be your escape route: your work becomes what you do to meet your basic needs and allow you to fulfil your desires. Living for the weekend. But as a mirror image of work, the idea of ‘leisure’ is no less alienating. Separating ‘need’ from ‘desire’ like this is always going to end with a fucked-up relation to reality. How do we fit them back together so that Sunday is no different from Monday?

0 notes

Photo

“The sin of property we do disdain…”

“Here was the true Great Spirit, the divine thread connecting all human endeavour – if you can keep it, it is yours. Your property, slave or continent. The American imperative.” – Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

Of course there’s nothing specifically American about the drive to seize people, things and spaces and claim them as your own. Whitehead acknowledges this when he say elsewhere that “one might think one’s misfortunes distinct, but the true horror lay in their universality.” That “true horror” is the capitalist imperative: to capture; to corral; to enclose; to own.

I wrote the other day that the slogan ‘everything for everyone’ is “open-ended, expansive. It has no boundaries”. That’s true. But as a comrade pointed out, it doesn’t mean that ‘everything for everyone’ does away with antagonism. In fact, the opposite is true: it’s totally antagonistic in a regime of private property. Demanding everything for everyone cuts that “divine thread”.

It’s easy to forget that the regime of private property that structures our lives is a relatively recent invention. In Britain, over the course of a couple of centuries, people were driven off the land, burned out of their homes, and turned into beggars, paupers and vagabonds. The enclosures were the launchpad for capitalism, creating a population who were ‘free’ from any means of reproducing themselves and therefore ‘free’ to become wage labourers.

“Stolen bodies working stolen land. It was an engine that did not stop, its hungry boiler fed with blood.” – Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

The enclosures were an unequivocal act of class robbery but they weren’t a one-time act. Enclosure is an ongoing process, an engine that does not stop. At times it takes brutally transparent forms, like the construction of Fortress Europe or the unrelenting erosion of public space in our cities. At other times, it’s more insidious, apparent in the ways people attempt to copyright ideas or engage in sectarian defence of their own organisation at any cost.

‘Everything for everyone’ flies in the face of all these enclosures. This land isn’t ‘mine’. Those ideas aren’t ‘yours’. These streets aren’t ‘theirs’. Instead, it demands that we take seriously the Diggers’ cry to make the earth “a common treasury for all”.

0 notes