Text

0 notes

Text

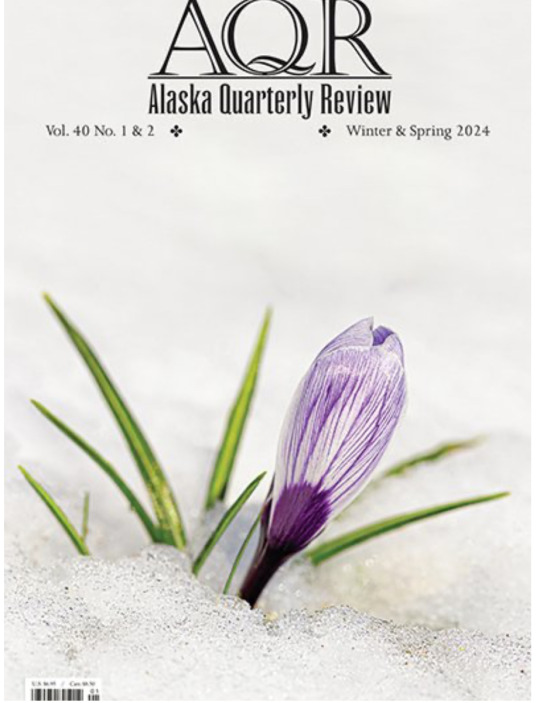

AQR Winter / Spring 2024

My story “The Shed” kicks off an issue of gorgeous fiction, nonfiction and poetry.

0 notes

Text

The Spring 2023 issue of Arts & Letters features "A Rapture Coming," my newest short fiction. Physical copies available now, digital issue coming soon!

0 notes

Link

“What Happens When I Give You Everything” is in the Spring 2022 issue of Passengers Journal.

0 notes

Text

The evolution and escalation of this story’s conflict happens naturally, progressing in a well-paced and believable manner that yields an ending which is surprising, satisfying, and inevitable all at once. The author of “So You May Sleep Again” depicts both the personalized and commercialized aspects of grief, while also showcasing the damage that can be done by loved ones who ultimately mean well. The assured voice of the narrator and the unexpected turns the story takes make this a perfect read.

-Amina Gautier, guest judge of the Beacon Street Prize, on “So You May Sleep Again”

0 notes

Text

My Beacon Street Prize in Fiction-winning story is now up at Redivider.

0 notes

Text

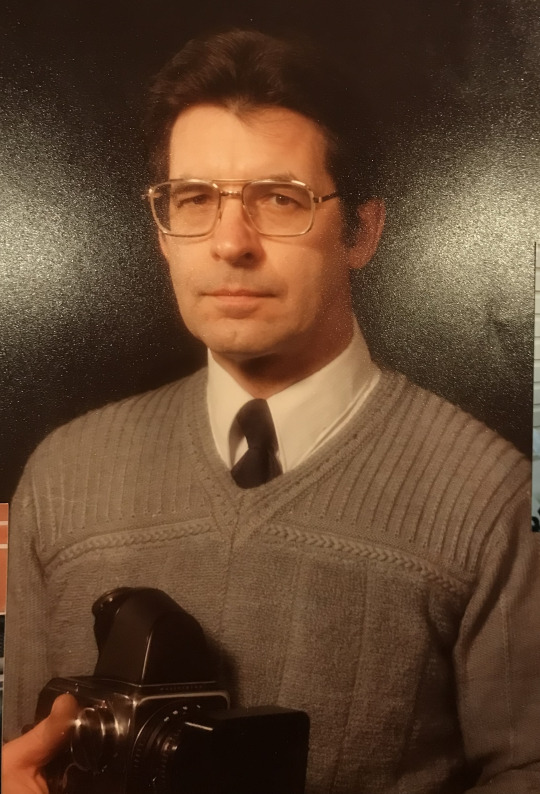

my grandfather.

When my mother called to tell me my grandfather was sick, I was underground. Sitting in my car in the parking garage up to the very minute before my shift started, listening to music, but, no matter how I rack my brain, I can’t remember which song. I do remember that the cell service was bad, so I could hear her but she could barely hear me. They found a mass, she told me, but that’s all we know.

I went through that shift in a haze, stopping to stare out the huge front windows that looked out on to a busy city street. A construction crew was working to raise yet another glass skyscraper right across Broadway, to be filled with more offices and more people. I remember thinking that day, Enough. But I also remember looking at the men in their hard hats as they shouted to each other, their hands gripping levers to elegantly control machinery that could topple buildings, and thinking of my grandfather. Because that was him– always working, always building, always precise.

My grandfather was a carpenter, a mechanic, a photographer, a gardener. He fixed tanks for the army, built model trains and made batches of homemade pickles. He had five children, fifteen grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren. He loved the ocean, mystery novels, lighthouses, and us.

The things I know about him are numerous and varied, but when broken into a list they seem like surface facts spread too thin over the vast plane of his life. It’s embarrassing how little I knew of him before me, or before my mother, the way we often think of everyone else’s life beginning just at the moment our own does. How everything before us was simply photographs. I know what he looked like in his army uniform, on his wedding day, holding his first child, because I’ve seen the pictures. I’ve seen the ocean in a hundred different frozen moments through his eyes, from the framed photographs in the family room of the house my mother grew up in. These things make him up, but at the same time, they don’t. What I know of him, what I hold deep in my bones that I will never forget, are his laugh, his large warm work-worn hands, his sense of confidence in himself and in all of us, and his great unshakable love. The things you cannot see in a picture or place in a list of accomplishments are the things I draw around me and hold when I am missing him- his dignity, strength, knowledge and endless, indefatigable love.

When I found out my grandfather was sick, I decided to go home. I’d been away for so long, since I went to school at eighteen. I was missing the people that are most important and I was ready to go back to Buffalo with no end date- I put in a leave of absence at work and booked a one-way flight. I wanted to spend as much time as I could with my mother, my brothers and most importantly, my grandparents. My grandfather’s doctors said he could still be around for a few years, and I didn’t want to miss any more of them. Three weeks before my scheduled flight, my grandfather was gone.

And so there was a new flight for a long weekend, and the first time all fourteen of my cousins and I have been in the same place in over ten years. A long weekend of unbearable sadness, a longing for the time that I had wanted- time to sit in my grandfather's warmth and let him know exactly what he meant. Instead I sat in the church my grandparents have attended for decades and watched my brothers help carry him down the aisle.

I did learn things about him during that weekend, but not directly from him as I’d planned. I learned he purchased his first camera from a thrift shop when he was on leave during his military service. I learned he dropped out of high school to work as a mechanic to help his family with money. I became even more convinced that he was the smartest and most capable man we knew.

When I think of him now, I feel the weight lift from my chest. It sometimes seems impossible to be kind in the world, especially now. But I think of him and it makes me want to try harder than I ever have before. It makes me want to be kind not for the possibility of receiving kindness back, but simply for what it will give other people. It makes me want to be kind because he was kind. It makes me want to take care of the people in my life the way he did. Sometimes I worry that I hadn’t done anything big to make him proud while he was here, but then I stop. Because it wouldn’t take a book deal or a literary award to make him proud. He didn’t like flashy, showy things. He liked right over wrong, and simplicity. I see him in my mother, my brothers and myself- we work hard and with our hands, like he did. He did ordinary things in extraordinary ways.

Now that he’s gone, most days I feel like going underground again and staying there. I stop in the middle of a sentence I’m reading and start to wonder if he would have liked this book, what the last thing he read was, what he would be doing right now. I’m still taking a leave of absence, still going home. My mother and grandmother will take me to try on wedding dresses and we’ll go out to lunch. We’ll sit in the family room with my grandfather’s photographs of the ocean on the walls and be together quietly. We’ll go into the basement where his trains are still on the table, and his dark room sits unused, and we’ll dig out my old doll and the clothes my mother sewed, stored in the white traveling trunk my grandfather made when I was little. I wonder if there’s a thing in my life that he didn’t make, and I wonder if now he forgives me for never thanking him.

I wonder, as I often have since moving out at eighteen– what is the price of leaving home? There are many things I wouldn’t have if I’d stayed, but many that I’ve missed. In my twenties I focused on where I was, and on seeing as much as I possibly could. Now, as thirty-two approaches, what’s become more important is who is there with me. And even though I can no longer hold his hand, I know my grandfather will be always.

0 notes

Text

A word collage made of text from The Book of X by Sarah Rose Etter, lyrics from mewithoutYou, quotes from The Radium Girls episode of The Dollop podcast, and text from my short story Fake Bodies.

0 notes

Link

I have an essay up at the wonderful Illuminations of the Fantastic, a magazine run by dear friends of mine in Nashville, TN.

0 notes

Text

in the field behind my house.

In the field behind my house, sways a wall of goldenrod.

I stand closer to the bees than I have ever dared before, watch their bodies, hear their hiss. I look for the queen.

Sometimes we run, the dog’s kicking strides alongside me, muscle rippling, claws tearing earth,

Strong in the way she is female.

I pound my legs to keep up. She glances as if to ask if I’m all right, as she should.

In the field behind my house, I relearn to breathe everyday.

I crash through grasses, feel my body work. I let in the earth and her trees, wasps, thistles, snakes, wind, water, crows. All women.

I wish for old growth.

There are lifetimes here where some would see nothing.

In the field behind my house, there’s a path that leads down to the stream,

On whose bed he asked me to marry.

It means now I must try harder, to be together but also separate.

I must try harder,

We must try.

In the field behind my house, I bury my dead.

My past selves, those little girls, as the sun shows her fangs.

I mark the graves with rows of thorns

to keep from digging them up.

In the field behind my house, the insects scream at night.

They fill that blackness with a voice, to find each other as much as themselves.

To join together,

As we all must.

0 notes

Text

lockdown.

During the pandemic we work at a grocery store.

It is loud in the store, even when it’s so quiet it hurts. Sometimes there are no customers and we walk the aisles, everything still and patient as though we are about to open the doors to a waiting crowd.

We begin to normalize our appearance, wide gaping white cloth mouths, bright blue plastic hands, the skin beneath cracked, pink and bubbling with eczema from scrubbing under water so hot the steam rises and clouds our eyes.

We rope off aisles and build walls of boxes in the produce department, constructing a frightening type of obstacle course. Kids would knock those boxes over, I think, and pull on the stanchions, but I haven’t seen a child in weeks.

The things we run out of are always the same— flour, chicken, toilet paper. Stacks of water cases litter the store like sandbags we can leap behind at the whistle of a dropping bomb.

We sit in our cars in the underground parking garage, too afraid to face each other over a narrow table in the break room. The chairs in the cafe are upturned. There are signs hanging everywhere, turning us away. No, no, no, they read. Step back.

A pile of used masks collects on my dashboard like gauze from a wound. After the first day, I removed a mask and saw in the mirror how my nose was visibly flattened. Now I don’t look in the mirror anymore.

We stand in the aisles and behind counters, wearing two pairs of gloves and bandanas over medical masks, and watch spandex-clad millennials go to the checkout with a coffee cup in one hand and a six-pack of beer in the other. We want to scream. We want to cry. We want to approach them, knock the coffee to the floor, stare them down. Stay home, we try to say with our eyes.

We are many millennials ourselves, but we want them to know that we’re different now. We age decades in the time it takes to disinfect our bodies in hot showers before we can hug our families.

We receive thank-you emails from corporate that we delete. They give us paltry amounts of hazard pay. They only begin to call us heroes when they know our risk outweighs any amount they would take themselves. We do not feel heroic. We feel we are watching the turn of the earth on a terrifying axis, as people who work where we do because we love food, we like to be on our feet, we need to move. We are artists, farmers, parents and partners. We do not wish to lay down our lives.

We feel we aren’t heard, so we yell. Less than six feet apart, because there isn’t the space in the back of house, we shout our conversations and somehow laugh wildly, raucously, big belly laughs that fill our masks and remind us that we’re here. In the break room a group of cashiers gossip loudly and in the corner near the refrigerator a Muslim man who works in the kitchen lays his chef coat on the the floor and kneels to pray.

We look at each other through glass and feel rushes of guilt and love when we get too close. All we want to do is hold one another’s hands, and even though no one would know if we did, just for a brief moment, we don’t. We wonder if we will ever touch again.

0 notes

Photo

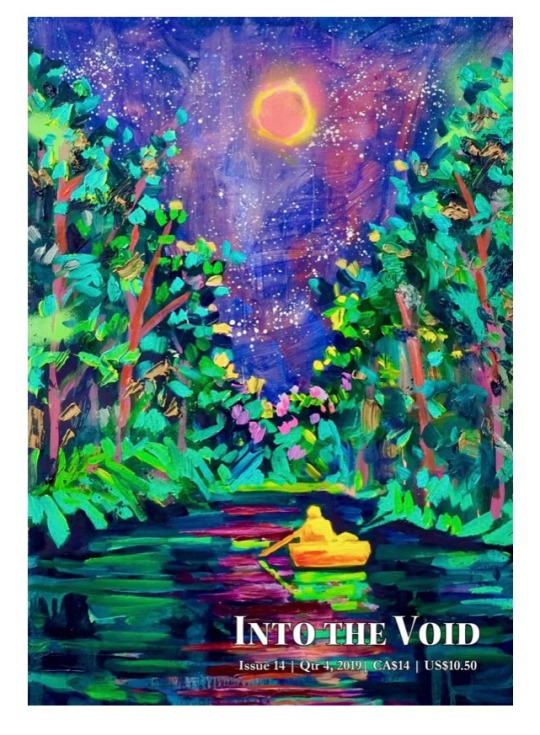

Into the Void Issue 14 includes “I Watched You from the Ocean Floor.” You can read it online or order a print copy at intothevoidmagazine.com. Xoxo

0 notes

Text

how we make a home.

I bought two plastic Adirondack chairs at the Home Depot in south Nashville today, $12 each because the weather is starting to cool. I carried them awkwardly through the parking lot, thinking that they’d definitely fit in my car, the bright blue Ford I only owe $5000 more on, and then they didn’t. A small Latino man stopped and motioned to ask if he could help me, so together we tried folding down the car’s back seats, pushing forward the front ones, clearing the bin of Frankie’s extra blankets from the trunk. A woman in a large SUV stopped as she passed and asked “How far do y’all live?” ”About ten minutes,” I said. “But I think I can fit them.” I’ve always had trouble accepting that generous kind of help.

Eventually the chairs did fit, one nested into the other in the front passenger seat. “Thank you, thank you,” I said to the man, really hoping he could tell I was sincere.

Years ago I bought two vintage dining chairs for a boyfriend’s twentieth birthday. I found them on the website of a store he’d mentioned and called to reserve them until I went to pick them up. The red line let me off somewhere deep in Cambridge, which to me was anywhere past Harvard, and I walked for blocks through sticky July heat. I followed the directions I’d written on a scrap of paper back at home; I still wouldn’t have a smartphone for years.

The chairs were waiting outside the store, lined up on the sidewalk along with other pieces for sale. The shop was small but open and airy. A woman with long wild hair sat at a table inside, pouring over a catalog. She was surprised; I’m sure her regular clients owned the large old houses up and down the blocks, or the townhomes on Commonwealth and Beacon. They usually weren’t college kids who had to call a cab to haul the furniture back to a small apartment with no central air. Because that’s what I did, the cab driver helping me load the chairs into the trunk and taking me back into Boston for twenty-something dollars plus tip.

Those chairs came with us to New Jersey and then to Nashville, the nicest things we owned. When the relationship ended, he got them. Of course he did; they were a gift, that I had hidden in my small apartment’s closet until his birthday, then revealed them along with a bottle of whiskey and a box of tea.

I’ve got some new dining chairs now, for the new apartment. I designed them online and had them shipped to my door. No scribbled directions on a scrap of paper, no subway, no cab. They’re beautiful and look great with the table. They’re light too, which will be good for when I move again. Back up north, where there are different bugs and different trees, and maybe people are less likely to offer to drive your chairs home in their SUV.

I bought the Adirondack chairs because they remind me of the chairs my grandfather made for my mother in his woodworking shop, real chairs with real wood and real gleaming varnish. Chairs too heavy to move, except the one time when she had to move them from her house to her apartment. When her relationship ended, she took them. And why wouldn’t she? They had always been hers.

0 notes