Text

Heading South

April 23 - Slav and I left Warsaw about 9:30 am headed south to Kazamierz Dolny, a small resort town on the Vistula River in the Lublin district. If that means nothing to you, it’s in south-central Poland. :) We were starting off our trip on a lighter note, exploring the churches, shops and natural areas in town, which had been reshaped in the 16th and 17th centuries by nobles and other wealthy builders who were fond of Reniassance architecture (a theme to be repeated over the next four days in the region). There was also substantial reconstruction after World War II.

The former synagogue, in a town which held one of the largest Chassidic courts in the country (led by the ‘Seer of Lublin’), is now a museum. This is also a recurring pattern in Poland - former synagogues serving as museums, schools, shops, residential homes and local community centres, because there are no Jews left. The few exceptions are in places like Warsaw, Lublin and Krakow, where small Jewish communities survive. Some of the people I spoke with mentioned never having met a Jew before.

Slav and I also toured a nearby small ravine, which is popular for hiking, and ended the day in the small city of Zamosc, where I stayed at the perfectly serviceable Hotel Mercure. This was to be my base for the next two days. The town square in Zamosc also displays Renaissance buildings, as well as a fortress that confronted everyone from local opponents to the Swedes and the Russians since the late 16th century. Slav’s research indicates that at least one of my ancestors came from this town. Jews were in fact welcomed by the first lord of the town, Jan Zamoyski, and one of his descendants, who was lord when the Nazis arrived, protected a number of Jews and others deemed undesirable by the Third Reich.

0 notes

Photo

Warsaw old city, memorial to 1944 Warsaw Uprising, memorials to 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. April 21, 2017.

1 note

·

View note

Text

From Russia to Poland

On April 20, my flight from St. Petersburg to Warsaw via Minsk crossed the snow line over Belarus, and by the time I got out of Warsaw’s Chopin Airport with my bags. I was pleasantly surprised to see trees with leaves. They were the light green leaves of early spring, my favourite. Unlike many other cities that insist on placing their airports a ridiculous distance away, the city centre of Warsaw is a fairly quick ride in. I stayed in a fair-sized apartment at the Diana Mamaison Residence, which I would certainly recommend to others.

The next day, I met up with Slawomir (Slav) over a good vegan lunch nearby and we confirmed our travel plans for the four days beginning the 23rd. Slav follows his late father in being a tour guide, researcher and genealogist focused in large part on Poland’s Jewish heritage. It’s hard to imagine now, when the country’s Jewish population is somewhere under 15,000, that in 1939, 3.5 million Jews made up 10% of Poland’s total population. Most of them spoke Yiddish as a first language. Three million of them were exterminated.

The focus of our journey was southeastern Poland, a large part of which was known as Galicia. Galicianer Jews had the reputation of being a little too clever (sneaky) and politically savvy.

Slav had carefully created an itinerary through the region that mixed the unspeakable (which is what I was there for) with lighter destinations, to give me time to absorb what I was seeing.

For a few hours that day, I got to play tourist. Most of the buildings in Warsaw’s old city are reconstructed, in part or in whole.

The Jewish neighbourhoods, which made up approximately a third of the capital, were almost entirely razed to the ground by the German occupiers. Only fragments remain of ghetto walls and prewar tenements.

I went to the prinicipal memorial for the fighters of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. I was accosted (for want of a better word) by a representative of the Chabad/Lubavitch organization, ultra-Orthodox Jews who follow the cult of the late Rabbi Schneerson, whom many of them saw as the messiah. He asked insistently if I would put on tfilin (Jewish prayer garments/straps) and pray at that site with him. I had to tell him no three times before he backed down. I have been told it’s something I should do because so many religious Jews were annihilated during the war. What they are neglecting is that there were also hundreds of thousands, if not millions, who led meaningful secular lives and perished all the same.

That night I attended a Warsaw Symphony Orchestra concert at the Polin Museum, which catalogues over a thousand years of Polish Jewish history. Everyone was wearing small yellow flower pins that looked like the stars Jews were forced to wear under Nazi rule. The concert marked the 74th anniversary of the ghetto uprising (April 19-May 17, 1943), which almost no one survived.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mauthausen, The Idyllic Hell

I’m not done reporting on the earlier part of my trip but I was at Mauthausen Concentration Camp today and wanted to get my thoughts down. I left my Linz hotel early this morning and took the tram to the central train station. It took less than an hour to travel east to the small town of Mauthausen, which is appallingly better known in the region today for having the only McDonald’s in the area (drive-through, in case you were wondering). The town streets, houses and yards are orderly, even picturesque in some cases, and signs boast of the superb local cuisine.

A taxi took me the 5 km up to the camp itself. The main gate and several other buildings, including some of the barracks, remain intact. The ‘Mauthausen Bistro’ serves small meals and snacks near the information centre and bookshop.

What was most striking and incongruous about the camp, particularly on a sunny and warm spring day, was how beautiful the camp’s surroundings were. Alps are visible in the distance, as are the rolling hills of the long belt of farm country that encircles the camp. One can see trees, flowers and agricultural fields just beyond the walls and barbed wire. In another universe, Mauthausen would have been an idyllic rural retreat.

My guide for the day, an earnest and intelligent young man named Daniel, met me at the bookshop and we began a private tour that is reserved for family members of camp inmates.

Daniel explained the layout of the camp, showing me before and after pictures, and we discussed what I knew from my mother and the correspondence she had received since 1965 about her father, from the Red Cross and the Mauthausen Archive, which has been maintained for many decades now in Vienna.I had written to the Archive months ago but they claimed there were no files in their possession about my mother’s father. Daniel said he had encountered this before and believed the relevant documents were still stored somewhere but had likely been forgotten due to staff turnover throughout the years.

What we do know about my maternal grandfather is that he was a ‘Red’ Cossack who was a communist and a Soviet Army Officer. He was captured almost right away after the Germans invaded the USSR on June 22, 1941. We do not know his fate in the intervening years but eventually he ended up at Mauthausen. Daniel explained that Soviet officers, especially political ones, were sent to camps within the German Reich itself, lest they become agitators in the camps farther east, in what is today Poland.

He died a few weeks after liberation in 1945, under the care of the 131st American Evacuation Hospital. He was no doubt as thoroughly emaciated and prone to illness as many of his comrades were. Even before liberation, he had likely been moved to the ‘sick’ part of the camp, which was next to the soccer field that I could see from the main camp above.

That field, I must mention, hosted an SS team that played games against other Upper Austria squads. Visiting teams and spectators would have seen barely surviving prisoners just metres beyond one of the goalposts, in the barracks and tents where hundreds if not thousands were kept during the later years of the war. In fact, the ground levelling necessary for both the soccer field and the sick area had been done by Soviet soldier prisoners and others in 1941. This was work that was as difficult as that being done in the stone quarries just beneath the main camp, where inmates carried slabs of stone on their backs to where they could be transported elsewhere. Even today, some Vienna streets remain paved by the products of forced labour, just as some of the surrounding villas in Mauthausen do.

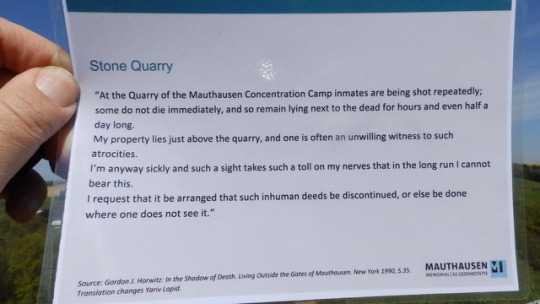

How else can we tell what the local population knew from early on? Among them were noise complaints lodged by farmers about noises of shooting prisoners and one woman (whose farm still stands today) saying already in 1941 that she had seen atrocities at the quarry below and it was harmful to her health to have that kind of activity around her. The SS ignored her complaint but moved executions by shooting to underground cellars eventually. Many of the locals also enthusiastically joined in on the so-called ‘rabbit hunt’ to kill and/or retrieve 200 Soviet prisoners who escaped in early 1945. They would have seen the condition of the escapees, and no one forced the locals’ participation, but they did it anyway.

Daniel was very open about Austrian attitudes today towards the camps. His older relatives felt he was shaming them by becoming a guide at Mauthausen. And had it been up to the Austrians in the first few decades of the war, there would have been no memorial at all. Nearby Gusen, for example, the site of a related camp, has a small memorial in a quiet space behind a housing development that was built over the camp - in fact, the main residential street runs exactly along the lines of the road running between the barracks that existed prior to liberation. In a disturbing piece of maintenance of period architecture, the former gate to the Gusen camp, which resembles the gate in Mauthausen, has been worked into a massive private villa.

It was only because the Soviet occupiers of that part of Austria insisted on a memorial that parts of the main Mauthausen camp were preserved. The camp was part of an industrial and killing complex that ran the length and breadth of Austria, even though some today try to pretend the camp was an isolated instance and people couldn’t have possibly known what was going on there.

On a positive note, high school students today (as with other camps I visited, no one under 14 is permitted entry) visit Mauthausen, and Daniel has led tours of some of the children living in that housing development in Gusen to provide them an alternative perspective on their homes.

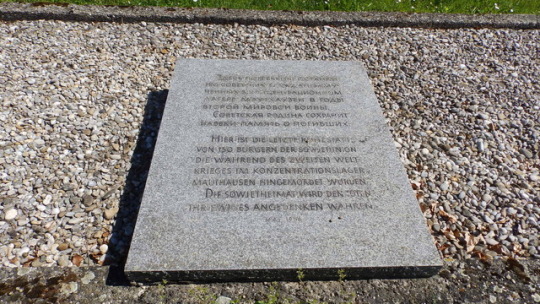

The American liberators made local Nazi officials bury the dead properly in the soccer field in 1945. There the remains stayed until Austria became independent again in 1955, when remains were transferred to mass graves inside and next to the camp and at Gusen. It is either in those graves or at the base of a Soviet monument in the camp (where the remains of 150 Soviet soldiers are buried) that my grandfather is buried. We’ll almost certainly never know where for sure.

Daniel was kind enough to take me all the way back to Linz, where he went to visit his mother. I spent the afternoon in Salzburg, trying to put aside for a few hours what I had witnessed earlier in the day.

0 notes

Text

The Ceremony

Waking up on April 17th to my first genuine hangover in 25 years, I shuffled around the hotel room until it was time for my day’s escort to pick me up and take me to the Ingria team’s headquarters at Saint Petersburg State University. Once again the TV cameras focused on my feet, this time as they staged me climbing the stairs to the second floor office. I was welcomed by team members and by the local head of the Veterans’ Association. I was interviewed briefly and thanked everyone involved for their efforts.

(I forgot to mention to you that during the previous day’s TV interview, the reporter commented that the grandson of a Soviet soldier was now a Canadian diplomat. I told him that I was in fact the grandson of two Red Army soldiers, the other being my mother’s father. More about him later when I get to Mauthausen, Austria.)

The Ingria office was decorated with WWII memorabilia, including an old-time radio and propaganda posters, as well as maps of the battles in the Lenigrad area. Professor Ilyin and his volunteers take their search for soldiers’ remains very seriously, with Ilyin having stated that he won’t consider the war over until the last soldier receives a proper burial.

I was formally presented the small medallion which contained the paper scroll identifying my grandfather, and the rest of his family, who as the scroll stated had been evacuated to the Kirov region. It was a great honour to receive the medallion and the scroll itself, which was less than intact after almost 75 years in the ground (in the medallion).

Team members walked me back all the way to my hotel and I spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around the city.

In the evening, I packed away the medallion and the Ingria badge the team had given me. They also provided me an engraved shell to store the dirt I had dug from both the mass grave and from the place my grandfather died.

0 notes

Text

A Pause to Write and Reflect

I’m finally taking a substantial breath for the first time since April 15th, when I arrived in St. Petersburg, Russia, after a quick early morning flight from Moscow. I am in Vienna tonight, after a week in Poland, preceded by five days in the Russian Federation. I will try to go in chronological order to give you a sense of what I’ve been doing and seeing.

First, the weather in St. Petersburg was mostly awful, especially for mid-late April. It snowed, there was a lot of ice and slush, and the winds were often bitterly cold. Score one for remembering to take hiking boots. These were particularly useful for traversing the mud and slush on the walk to where my grandfather fell. I should have taken gloves and a good hat, but I was already overpacked as it was.

I have to say that the food was really good in the St. Petersburg area, the people were mostly friendly and the city looked fairly prosperous. My centrally located and comfortable hotel room at the Domina Prestige was resplendent in purple and I enjoyed some rest to recover from a bit of jetlag - the city is seven hours east of Port of Spain/Ottawa/NYC time. I took a walk to St. Isaac’s Cathedral and shuffled carefully over the ice around part of the city centre.

The next morning, the 16th, I was picked up shortly after nine by Dasha, a young Russian woman who was my assigned driver for the day, courtesy of the Ingria team of the St. Petersburg State University. Dasha took us in her Lexus to meet some other members of the team, Alex, Alexandra (my trusty translator), Sergei, Alex, team leader Prof. Yevgeny Ilyin, and Maria Khodesevich, who was the person who discovered my grandfather’s remains. They are all impossible sweet people. I felt truly cared for during my two-day program with the team.

Also joining us in the two-vehicle convoy was Tatiana Gord, a print journalist for St. Petersburg Evening, and we were eventually followed by another car with a TV (78 ‘Life’) news crew. I had no idea my visit would attract so much attention but the media activity sustained itself for at least the two days I was there.

We exited the city eastward towards the town of Kirovsk. My father (born in 1938), his two older brothers and his mother were evacuated to the Kirov region in 1941 from the Russian city of Smolensk, which had fallen to German forces earlier that fall. We don’t know how long they were in Smolensk or what their exact path was from Poland in September 1939.

We do believe that my family saw my grandfather not long before he returned to the front for a final time in November-December 1941. He and his comrades participated in one of the first large efforts to break the German-Finnish siege of Leningrad, as it was then known. The siege ultimately lasted over 900 days and killed over a million people, plus well over a million Soviet soldiers. Prof. Ilyin believes my grandfather belonged to the 204th regiment of the Red Army; I have been unable as yet to find any information on this grouping.

Our first stop outside the city was at a Panorama Museum site built c. 1984. The interior was stunning. It portrayed the Soviet front lines and a panorama of the region from Lake Ladoga in the north to the Gulf of Finland in the south. It was an apocalyptic vision, with fire everywhere, bombers overhead, and doomed soldiers moving en masse across land and sea in an attempt to free the starving masses of Leningrad.

Outside, we walked past various tanks used by Soviet forces during the war, including one that was painted white for winter warfare. The fastest tank there could reach over 60 kph but this was a war of attrition for the longest time.

The next place we visited was the Sinyavino Heights War Memorial, where soldiers of the 1941-44 Soviet offensive were buried. My grandfather, who was discovered on May 5th, 2015, was interred there in a mass grave the next day. I had thought there was a headstone for him but there isn’t one - yet. I intend to rectify this situation eventually. The location of the gravesite on the Heights is indeed poignant - it was the target of my grandfather and the forces with him.

I placed flowers at the mass grave and we lit candles of memorial. Tatiana gave me a stiff belt from her flask, as she had done outside the Panorama Museum. The TV crew was obsessed with showing me walking everywhere, trudging through the snow and mud. I swear they had cameras trained on my feet for a total of twenty minutes or more. It was a solemn experience otherwise and I had a strange feeling of a circle being closed, standing so near the mortal remains of my grandfather.

We continued by car and then eventually on foot to where the Ingria team conducted many of its searches. The place is forested now but Prof. Ilyin stated that the whole area was like a vast desert by the end of the war. The amount of bodies, bullets and other remains of the war cover vast regions around what was then Leningrad. There are homes built over some of these battlefields and not every homeowner will give permission to have searchers retrieve bodies. Not everyone will have the same opportunity for closure that I did.

We finally reached the former trench where a mortar killed my grandfather and no doubt many of those around him. The team retrieved my grandfather’s gas mask and shoes, as well as a ceramic cup from nearby that may or may not have belonged to him. We also took some dirt from the ground where he had been found, as we had done from the mass grave. Once again, the soil was full of bullets, which caused me some trouble going through Customs on my way out of Russia. I laid a flower at the site and stood in contemplation of what had happened there. The TV crew interviewed me via Alexandra and started off with a tricky question about Canadian-Russian relations. I deflected and said this was all about family, and I thanked the team for finding my grandfather.

Kirovsk and its main Russian Orthodox church were also on our route. I was invited by a team member to take pictures of the old heating system in the local corner store, much to the chagrin of the woman running it. My friend said it was a good thing at that point that I didn’t speak Russian.

Our final travel stop was a memorial near the banks of the Neva River, still on the eastern side. The memorial is the site where remains were gathered during the conflict. Prof. Ilyin said the phosphorus from the bones caused a white glow to hang over the area for a long time. We walked down to the river itself. Human remains were clearly visible, 75 years later. Where there weren’t bones, there was ammunition - the Germans were just across the river. It was a thoroughly chilling sight. Yevgeny told me the average lifespan of a Soviet soldier who fought there was one day and eight hours.

I returned to my hotel and soon after, I took five of the team members out to dinner at The Idiot (named after a Dostoyevsky novel). There was much drinking and conversation about history and politics, and I felt absolutely privileged to be in the company of such amazing people, and to have had the chance to ‘visit’ my grandfather, who died a quarter of a century before I was born.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last minute passport drama

I obtained my Russian visa several weeks ago and was looking forward to getting an Algerian visa, to visit a friend and spend some quality time in the desert. Well, my friend’s delays in getting me a letter of invitation put things pretty close to the wire, but I dutifully couriered the application and my passport to Caracas, the site of the closest Algerian embassy, which it never reached. The Venezuelan National Guard intercepted the package and somehow claimed to DHL that they suspected a drug transaction. Really? A Canadian passport, USD80 (the embassy had insisted on cash) and a passport application with three photos? It took days and the combined efforts of my colleagues to recover the passport (sans Algeria visa) which reached me this afternoon. Consequences: I can travel, but not to Algeria and I had to eat the costs of tickets there and back. I am now travelling to Morocco instead, to have some decompression time before I return to Port of Spain. But at least I can get on the plane tomorrow!

1 note

·

View note