Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Best books 2024

I started writing this at the end of last year but was distracted by other things. Now however, I’m sick and stuck at home so here it comes. 2024 was a year of many (great) reads. I had a hard time narrowing down the list, so here are the 10 best books I read in the past year in no particular order.

Om udregning af rumfang [On the calculation of volume] I-V – Solvej Balle

2024 was the year I started reading and became obsessed with Solvej Balle’s septology about a woman who gets stuck in the 18th of November which she relives again and again and again. I’ve had a hard time finding a way to convince people to read it because the plot sounds really boring but it’s such a great exploration of time, love and human relationships (and it also made me scared to wake up and being stuck in time).

Kære fuckhoved [Dear dickhead] – Virginie Despentes

Despentes’ book is a modern epistolary novel. It is about Rebecca, an actress who has been famous for her beauty and wild lifestyle who approaching middle-age, experience decreasing attention from film makers and the public, and Oscar, a younger author. They don’t know each other but Oscar makes an Instagram post where he insults Rebecca’s looks which prompts her to write him an angry e-mail. Thus starts an e-mail correspondence between the two in which they slowly, through discussions, disagreements and everyday reflections, become friends. It’s a novel both about MeToo and Covid and despite how annoying that sounds, it is not. I’ve described the book as utopian because it insists on the possibility of reconciliation and of people’s ability to change.

Deep purple – Christel Wiinblad

This strange book is a mixture of prose and poetry which revolves around the suicide of her younger brother but also about her childhood and various relationships. Reading it was an almost trance-like experience, I couldn’t really shake off afterwards. It also led me to this touching interview (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CsWqpQVn0cA) with her about an earlier poetry collection she wrote about him where he plays with his band at the end.

The wren, the wren – Anne Enright

An author I’ve been really happy to discover this year is Anne Enright. Her novels are simultaneously incredibly funny and incredibly touching. This one, about a woman in her early twenties, her mother, and their relationship to the mother’s father who was a famous Irish poet, made me laugh several times and at the same time manages to depict family relations in all their complexity.

On women – Susan Sontag

Based on my politics and taste in literature, I should be a Sontag-fan, but I have never read that much by her except from the first volume of her diaries and some excerpts of her writing on photography. This collection of some of her essays and interviews on women and feminism which I picked up in a bookstore in Porto turned me into one. I really admire the way she manages to be argumentative and nuanced and reflective at the same time. I think everyone should read the essay On the double standard of aging. After reading that, I decided to stop being a girl and start being a woman (I don’t know whether I managed to do this in practice...).

Baumgartner – Paul Auster

I have a soft spot for widows, in particular widowed men: I once cried hysterically for half an hour after watching a documentary about a weekend course for recently widowed people to learn how to live by themselves. The last book Paul Auster, who I’ve never read anything else by, wrote before he died which is about a widowed professor likewise made me cry with a scene in which he wakes up and briefly forgets that his wife has passed. However, it is not primarily a sad book: it is both about the love he experienced with his wife, but also the possibility to LOVE and EXPERIENCE JOY again and again. Almost a feel-good novel...

Hvis du bankede på min dør [If you knocked on my door] – Patrizia Cavilli

I don’t read a lot of poetry, but I read this in a dreamy state – it reminded me of Adrienne Rich or Audre Lorde’s poetry, with its descriptions of everyday situations and city flats interior mixed with love and politics, although as one poem states “my poems won’t change the world”.

Minor detail – Adania Shibli

The scandal around the withdrawal of the Frankfurt bookfair prize to Shibli for this book has in some way overshadowed the book itself but, in a way, these events reflect its themes. In the book, a Palestinian woman reads about the rape and murder of Bedouin Palestinian woman by Israeli soldiers in 1949 which happened on the same date as her birthday. Because of this “minor detail” she decides to visit an Israeli archive to investigate the incident, which due to various circumstances related to the occupation becomes rather difficult. I went to a talk with Shibli where she said that in the book, she wanted to explore the normalization of the act of killing, and to see historical archives as a gathering of narratives from a specific perspective, rather than an objective recollection of history.

Menneskeslægten [The Human Race] – Robert Antelme

Some years ago, I read Marguerite Duras’ La douleur which mesmerized me and which I talked about non-stop to anyone who’d listen. La douleur is about the end of the second World War and how Duras is waiting in liberated Paris for her husband who has been interned in a concentration camp to return. During his absence, she has been active in the resistance movement and has fallen in love with another man. The Human Race, written by Antelme, her husband, documents his time in Nazi captivation. I have a hard time formulating my feelings about it. In many ways, it was horrible to read: the treatment by the SS, the constant lack of food, the deaths, and the ubiquitous lice. But Antelme writes about it in such an unsentimental way – even the descriptions of the small acts of kindness between prisoners and the way he avoids thinking about Duras back in Paris.

Franzas bog – Ingeborg Bachman

A large part of this book revolves around a long train journey and fittingly, I read it on a long train journey. Franza flees her abusive psychiatrist husband and joins her brother Martin, who studies archeology, to an excavation in Egypt. While the book is somehow unfinished (Bachman died before she finished writing it), it manages to weave together oppression of women, colonialism and World War II trauma in a strange, feverish narrative. What I liked most though, I think, is the depiction of the relationship between the two siblings which now that I think about it has some similarities to Wiinblad’s Deep Purple.

I don’t have many intentions for my reading in 2025 except that I should try to read unread books I own before buying new ones, and that I should maybe give male authors more of a chance this year – I think I want to read more Paul Auster for example.

0 notes

Text

What else actually is there? - Jenny Turner on Gillian Rose

0 notes

Text

Women have been accustomed so long to the protection of their masks, their smiles, their endearing lies. Without this protection, they know, they would be more vulnerable. But in protecting themselves as women, they betray themselves as adults. The model corruption in a woman’s life is denying her age. She symbolically accedes to all those myths that furnish women with their imprisoning securities and privileges, that create their genuine oppression, that inspire their real discontent. Each time a woman lies about her age she becomes an accomplice in her own underdevelopment as a human being. Women have another option. They can aspire to be wise, not merely nice; to be competent, not merely helpful; to be strong, not merely graceful; to be ambitious for themselves, not merely for themselves in relation to men and children. They can let themselves age naturally and without embarrassment, actively protesting and disobeying the conventions that stem from this society’s double standard about aging. Instead of being girls, girls as long as possible, who then age humiliatingly into middle-aged women and then obscenely into old women, they can become women much earlier—and remain active adults, enjoying the long, erotic career of which women are capable, far longer. Women should allow their faces to show the lives they have lived. Women should tell the truth.

Susan Sontag, "The double standard of aging"

0 notes

Text

On portraiture: Nan Goldin, Alice Neel and Apolonia Sokol

Nan Goldin, Picnic on the esplanade, Boston, 1973

Back in December, I visited an Alice Neel exhibition at the Munch Museum in Oslo which left a big impression on me. When I got home, I started writing an essay about Neel and portraiture which I since abandoned. When I watched the documentary All the beauty and the bloodshed about Nan Goldin two weeks ago, I however started thinking about it again. The documentary, co-produced by Goldin, follows her battle against the Sackler family. The Sacklers are the world’s largest producer of opioids and are seen as being the main drivers of the opioid crisis. For decades, they’ve pushed for increasing prescriptions of opioids, despite being aware of them being incredibly addictive, thus sending hundreds of thousands of people into addiction – a large number of these addictions resulting in deaths. At the same time, the Sacklers are great patronages of the art world and has donated millions of dollars to art museums all over the world, who in turn have named wings, courtyards and buildings after them. Goldin, herself a survivor of opioid addiction, form the activist group P.A.I.N with other survivors and people who have lost loved ones to the same. The group’s goal is to have the Sackler name (and money) removed from museums around the world, to make impossible their art-washing. This narrative is interspersed with Goldin’s own life story and her photography.

Goldin is one of the first artists I remember leaving an impression on me. I stumbled upon her photography on the Internet and was captured by their overwhelming intimacy. Years later, I saw The ballad of sexual dependency exhibited at MoMA in New York. Goldin exhibits her photos in a slideshow accompanied by music, which means that the viewer is made to watch each photo in a specific order and for a specific time. I was mesmerized by this way of curating photography and bought her book of the photos afterwards. I’ve seen the slideshow exhibited again later where she had added new photos to it and made changes in the order. The unfinished and unfolding nature of the slideshow reflects Goldin’s attitude to photography.

In the documentary, Goldin recounts running away from home at age 14 following the suicide of her older sister. At the various institutions where she spent her teenage years, she was shy and had difficulties connecting with her peers. That was until she 1) met David Armstrong who became a lifelong friend and 2) took up photography at age 18. The camera, Goldin says, gave her a reason to be there. She had a purpose: documenting. Throughout her life, she has continued photographing the people surrounding her.

Alice Neel, Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian, 1978

This made me think of Alice Neel again. Neel lived from 1900 and died in 1984, just before Goldin made her debut in the art world. She is considered one of the 20th century’s greatest portrait painters but didn’t want to be called that but referred to herself as a “people painter”. Like Goldin, she portrayed the people who surrounded her: friends, people in her neighborhood, artists and leftist intellectuals. “One of the reasons I painted”, Neel said, ”was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle, because when painting or writing are good it’s taken right out of life itself, to my mind.” The people appearing in her paintings recall the sitting itself as joyful, as they talked and laughed with Neel non-stop. However, many thought that it was an eerie experience seeing the result (Frank O’Hara famously hated his portrait). She called herself a “collector of souls”, meaning that she wanted her paintings to show more than the way her subjects looked physically: she wanted to convey their being. It’s not that she made them look unpleasant. It’s rather that the subjects look somehow wonky: some body parts are slightly enlarged, certain colors are exaggerated or distorted. Strangely, this makes them seem more rather than less lively.

Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

Similarly, Goldin wants to capture the lives of the people she photographs. More than Neel however, her subjects’ opinion of their portrayal matter to her. In All the beauty, she recounts how at early screenings of her slideshows, the audience would consist exclusively of the people appearing in the photos who would comment loudly on what they thought of the photos of themselves. This would lead her to keep some and remove other photos from show. In The ballad, she writes: “My desire is to preserve the sense of people’s lives, to endow them with the strength and beauty I see in them. I want the people in my pictures to stare back”. Her subjects, her friends, were marginalized – queers, drug users, poor artists — deemed as outcasts by society, and she wanted the photos to challenge this gaze. The photos showcase beauty and community, from the mundane (picnics, breakfast) to the celebratory (parties, night clubs, weddings) as well as in moments of griefs and hardship (funerals, Goldin’s unforgettable self-portraits after being battered by an ex-boyfriend).

Nan Goldin, Max, Muffy, and Peter at Sharon's birthday party, Princetown, 1976

The inheritance of Neel as well as Goldin’s approaches can be traced in Apolonia Sokol’s work which I first got to know through the extraordinary documentary Apolonia, Apolonia. Similar to both Goldin and Neel, Sokol often paints those marginalized by mainstream society, queers, racialized subjects, activists: her friends. Like Goldin, she wishes to convey them how she sees them, and how they deserve to be seen.

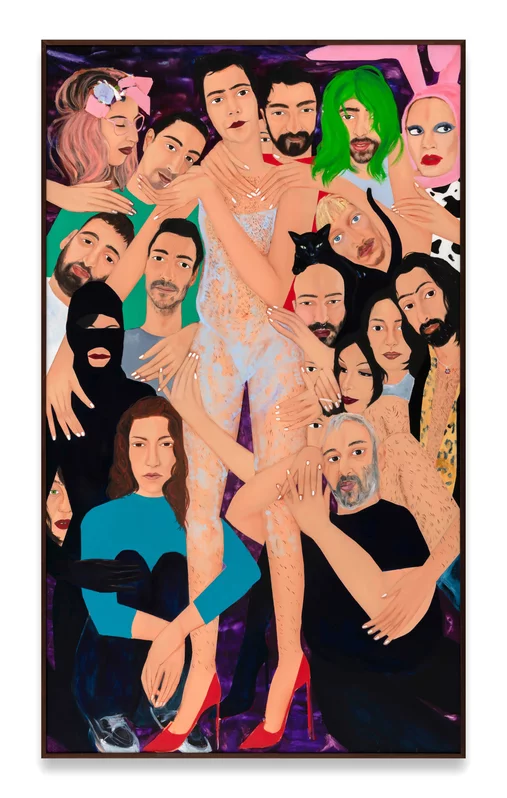

Apolonia Sokol, Boysan with friends, 2022

This is somehow also where she and Neel have different ideas of what it means to portray. Sokol’s subjects are radiant, a portrayal which can be read as resisting how her subjects are usually depicted by society: as misfits, abject, unwanted. Filtered through Sokol’s eyes, they are instead strong, majestic, beautiful. She often paints them in warrior-like scenarios, holding the cut off heads of men; protesting at demonstrations; carrying swords: almost always with a defiant look on their face. Neel on the other hand shows the vulnerabilities of her subjects, their ambivalences and insecurities.

Apolonia Sokol, Dina, 2022

Alice Neel, Frank O'Hara no. 2, 1960

For both Goldin and Sokol, the relationship to the subject is central to the artwork. To Goldin, her photos are not only portrayals of the people in them, but of her relationship to them: “There is a popular notion that the photographer is by nature a voyeur, the last one invited to the party. But I’m not crashing; this is my party. This is my family, my history.” Documenting becomes a way of preserving these relationships. It was David Armstrong, her first real friendship, who made her pick up the camera to photograph him, and it has been this way ever since. The act of documenting is however ambivalent. Goldin has said about her documentation, “I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I've lost.” In All the beauty, this becomes painfully evident. Photos of her friends taken in the 70s and 80s slide by, while she tells us that most of them died not long after, mostly of AIDS.

Nan Goldin, Cookie in her casket, NYC, 1989

One of Sokol’s most frequent subjects is her friend, Oksana Sjatjko. Sjatjko, herself an artist, who was part of the feminist collective FEMEN and had to flee Ukraine for France, moved in with the rest of the group in the theater in Paris, Sokol lived in. They became close friends. When the rest of the group found other places to live, Sjatjko stayed. When the news about Sjatjko’s death is delivered in Apolonia, I couldn’t stop crying. I cried throughout the rest of the film, I cried through the end credits and when I woke up the next morning, I was still feeling sad. It wasn’t only her tragic death, it was the film’s portrayal of their friendship, from the scenes where they read paperbacks and smoke cigarettes together in bed, to Sjatjko posing for Sokol and accompanying her as support to various exhibitions, to them bickering, complaining about each other, only for a moment later to be laughing with each other.

For the two, being friends was not always easy, is the impression the documentary leaves you with. Sjatjko was traumatized by her flight from Ukraine, battling the French integration bureaucracy as well as her growing ambivalence towards FEMEN’s political strategies and her own future. Sokol was restlessly moving around the world, from Paris to Copenhagen to Los Angeles, fighting for her work to be recognized. These difficult life situations made them close to each other, while at the same time leading to tensions and disappointments.

In a way, these ambiguities are not immediately evident in the paintings of Sjatjko. Here, she looks glorious, in some paintings depicted in the style of an orthodox icon, in another with her fists raised, ready to fight. Looking closer at the latter painting however, you realize that both of her arms are in casts, a reference to her breaking both of her arms when jumping out of a window to escape capture in Kiev. This relationship between strength and vulnerability is also present in another painting where Sjatjko locks eye with the viewer, however with half of her face partly hidden behind her hair.

Apolonia Sokol, Oksana, 2024

What makes the work of these artists so interesting and immediate to me, is the way it opens questions of friendships, remembrance, glorification, celebration, marginalization and politics and the ways in which they become intertwined in ambiguous ways in portraiture. Portraiture can never mirror reality in any objective sense, but it shows us something much more interesting — especially when it’s not trying to do the former.

0 notes

Text

On a writing retreat. I can see horses from my window and today it started snowing.

0 notes

Text

Books of 2023

At the end of the year, I look through my diary where I note down the books, I have read this year and gather them in a list. I read quite a lot (this year, I’ve read 57 books) – naturally, some are better than others. Here are my favorites from 2023.

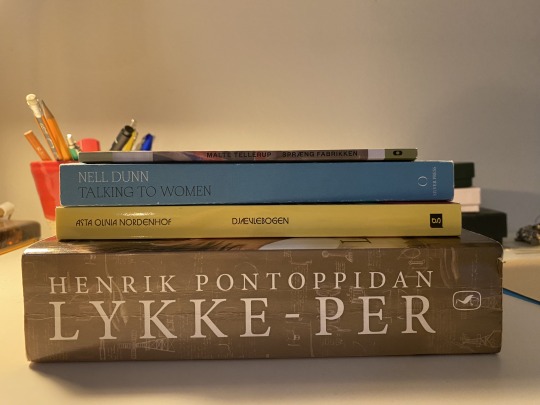

Some of the books but not all because this year, I borrowed a lot of books from the library and from my friends who all have great taste.

Janet Malcolm: In the Freud archives (1984) and The journalist and the murderer (1989)

I’ve been introduced to many of my favorite authors by my friend Nanna, who in the beginning of this year lent me In the Freud archives, a journalistic encounter of a conflict in the psychoanalytic milieu in New York about Freud’s legacy, more specifically, about Freud’s relation to the seduction theory. The book reads like a crime novel while also asking fundamental psychoanalytic questions. Why does it matter so much what Freud thought about the seduction theory, I thought to myself at the beginning of the book. Quite a lot, it turns out. The journalist and the murderer changed the way I think about interviewing and representations, and I think everyone who works with written representations of people should read this. I’ve been schooled in thinking about ethnographic representations through a political and decolonial lens but The journalist made me think about it through psychoanalytical terms as well – the impossibility of representing others reflect the impossibility of knowing yourself fully.

Nell Dunn: Talking to women (1964)

I finished this book in January when I was on a writing retreat in Skagen at an old refugium. Outside, it was cold and windy, the days were short, I sat inside by my desk, attempting to finish an article. At night in bed, I read Talking to women, a collection of interviews Dunn made with women she knew about love, work, motherhood – in other words, about life. Although the interviews are from the early ‘60s, they convey recognizable aspects of womanhood, both the pleasures and the pain. Dunn’s interview isn’t the detached style of a journalist or a sociologist but that of a friend: she intervenes, discusses, comforts her subjects, resulting in the interviews also demonstrating female friendships.

Elena Ferrante: Days of abandonment (2002)

This is the first Ferrante book I’ve read outside of the Neapolitan quartet. I think it’s one of the bravest books I’ve read about what love can do to you – I’ve written about the book’s qualities in another blogpost, so I won’t say much more about it, just that it shook me deeply with its painful depictions of betrayal, disappointment, and jealousy.

Henrik Pontoppidan: Lykke-Per (1898-1904)

My stepmum gifted me this book years ago but I’ve never gotten around to reading it until this summer, expecting it to be one of those boring classics you are forced to analyze in Danish class. I never heard much about it what it is actually about: the story’s hero, Lykke-Per, grows up the son of a very conservative priest in Western Jutland but early on rejects his family’s way of living, and decides to move to Copenhagen and study engineering. Here, he befriends several members of the establishment, makes great engineering plans for Denmark, and tries to marry into the bourgeoise and leave his background for good. However, in my opinion, the real hero of the book is Per’s fiancé, Jakobe, the extremely intelligent daughter of a wealthy Jewish family who’s trying to find her way in the man-dominated world she feels uncomfortable in. It's a book both about the modernization of Denmark, as well as an existential story about getting what you want and then not wanting it, about human relationships, about antisemitism, about women’s struggles and a page turner? I think I’ll return to this book in the future.

Fleur Jaeggy: Sweet days of discipline (1991)

I love ominous books about communities of girls and women, and this was no exception. It takes place in a Swiss boarding school and is written in the first person, but the narrator remains elusive, impossible to grasp outside of the group of women. “When you’re in boarding school you imagine how grand and free the world is, and when you leave, you’d sometimes like to hear the sound of the school bell again”. More Fleur Jaeggy in 2024!

Malte Tellerup: Spræng fabrikken (2023)

I couldn’t stop 1) thinking about this book and 2) telling everyone who would listen about it. It’s a very short book which a reviewer called ‘anti-literature’ – it’s about three young people living on a small farm where they experiment with regenerative agriculture when they are told that they will have to leave the land due to the neighboring chemical factory expanding. They give up their farming and instead start making bombs for attacking the factory. I’m planning on writing a separate post on this book, so I won’t say much more other than this being the best piece of ‘climate literature’ I have read.

Asta Olivia Nordenhof: Djævlebogen (2023)

Nordenhof was maybe the first contemporary author I read who demonstrated how literature can be political and personal at the same time with her poetry book “det nemme og det ensomme” (the easiness and the loneliness). I’ve longed for this book, the second in a planned septology, since she published the first one in 2020 and read it in one setting. It’s about the possibility of love under capitalism, about money, sex work, strange encounters and mixes the novel with poetry. Here’s (a badly translated) part of the poem which makes up the introduction in which she describes her troubles with writing the book:

“my motto/which I had forgotten/while I was struggling/to write a/real book/about the inner life of great men/my motto/here it is/it is simple/and great/fuck men!/when I remembered this/I remembered/that I can do/what I want.”

Natalia Ginzburg: All our yesterdays (1952)

Sally Rooney described this as a perfect novel, and I would agree. It’s about a family living in fascist Italy with the youngest girl of the family as the protagonist who however doesn’t take up more space in the novel than the rest of its characters which the novel follows through the Second World War as some of them join the resistance and others find other ways to cope with fascism. The novel explores the impact fascism and war have on different people, without viewing this as a reflection of essential character traits or depicting some as inherently evil and others as inherently good. Ginzburg has an eye for the small things that make up people – certain turns of phrases, bodily manners, temperaments – and the necessarily ever-changing relationships between them, writing about these with great feeling and humour. I enjoyed the way the novel treats politics and politicization not primarily through public life, but in the personal relationships of the characters.

I’m quite satisfied that only one (!) US-American author made it onto this list. Next year, I’d like to read more authors from the Global South and perhaps even more POETRY. I also want to continue reading the same books as my friends because literature is, truly, best when discussed with others. Until then, I’m off to buy champagne and lemons for New Year’s Eve – see you!

#feminist literature#elena ferrante#natalia ginzburg#henrik pontoppidan#asta olivia nordenhof#fleur jaeggy#contemporary literature

0 notes

Text

Communal luxury

My goal for the end of this year is to finish the stack of half-read books on my nightstand. I've been reading one of these books Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune by Kristin Ross from 2015 since late June, but put it down and didn't pick it up until last week, despite of it being quite short. It's about the political thoughts that inspired the Paris Commune, and how the Commune inspired political thought, both with former Communards and with socialist thinkers around the time in general. It was a bit too scattered for my taste - I thought it lacked a clear narrative - but I anyways enjoyed parts of it, especially how the idea of the Commune, not as an isolated 'intentional community' but as universalized communaization, was born with the events in Paris. I've been reading a lot of communization theory recently (primarily EndNotes and M.E. O'Brien), and the trajectory from the political imaginary laid out by Ross to this is quite clear. Also, I always enjoy historical accounts of political engagement that mirrors contemporary (read: my own) experience, such as the quote above by William Morris waling in a procession dedicated to the memory of Marx 'at the tail of ... a very bad band'. I also found Communard Gustave Lefrançais' description of working together with anarchists very sweet:

0 notes

Text

Hollow land: Israel’s architecture of occupation - Eyal Weizman

0 notes

Text

How to blow up a pipeline

The evening before I saw How to blow up a pipeline in the cinema, I coincidentally watched Ocean's 11 at home. I thought that was why they reminded me of each other - but then I read an interview in Lux Magazine with Ariela Barer, who plays Xochitl and is one of the film's writers, in which she herself makes the comparison: "I wanted Ocean's 11 for climate radicalism". The plot goes something like this: Xochitl and Shawn are university students involved in the divestment movement but are both frustrated with the slowness of this strategy, and decide to take to direct action: as the title of the film suggests, they want to blow up an oil pipeline. They reach out to people affected by either environmental problems or by the oil industry in different ways, and ask them to join.

The activists in the film don't have much in common except for their exposure to environmental damage and their different stages of political depression in the face of the climate crisis. But in this case, that is enough to get the job done.

Usually, films about leftist activism or experiments end up showing how they are doomed to fail due to in-fighting and egotism, or simply that it is utopian, unrealistic and childish to think that it is at all possible to think we could do things differently.

(the worst ones seem to try to make the point that activists are not really motivated by political reasons - that it is all really about individuals who want power in a way that somehow makes them worse than what they are fighting against, be it fascists or capitalism)

There's a lot of things one could criticize How to for. At times, the dialogue feels a bit trite, and the back stories of the characters are on the verge of being too US-American sentimental. Its main attraction though, for which I forgive the former, is that it is neither condescending or admonishing towards activism. Instead, it shows that political action is meaningful and that it is possible to put aside our egos and work through our differences in order to do it. There's a meme in which people comment "this cured my depression" on for instance YouTube videos of particular songs. Well, How to cured my political depression.

0 notes

Text

Is cultural appropriation in again?

I recently returned from Denmark’s (arguably Northern Europe’s) biggest cultural event, Roskilde Festival. In addition to a serious cold, I’ve also come back with questions about fashion. I never got this myself when I went to the festival as a young(er) person, but Roskilde is where you bring your hottest outfits and possibly experiment with your style (aged 15-20, I always just brought two pairs of shorts and a handful of ugly band t-shirts, as if I was a middle-aged rock dad). While under way for a couple of years, Roskilde showed that Y2K-fashion has really come back in style, not only amongst the techno crowd but with everyone. Everywhere I turned, I saw low rise jeans and bellybutton piercings. I can’t say that I am free from its influences myself - I have too much Adidas in my wardrobe for that. Anyways, while I won’t pretend to know anything about fashion, one thing struck me about this Y2K-resurgence: it is being accompanied by what would have been described as cultural appropriation ten years ago. When the Y2K-trend was on its way out in the 2010s, it was especially in the online feminist community criticized for cultural appropriation, as there was a tendency for white people to heavily incorporate elements from non-white cultures in their style. Many are the blog posts I have read about Gwen Stefani’s different phases of cultural appropriation in the 2000s. Now, some of these criticized trends are back. White people are wearing rhinestones in their faces approximating Hindu bhindis, flower crowns like those popular at Coachella 10 odd years ago which were then criticized by some as appropriating Mexican culture. One of the larger criticisms if I remember correctly was how much of the style originated from Black US-American culture, especially the style of R&B artists like Destiny’s Child.

I’m not going to try to determine what constitutes cultural appropriation and what doesn’t. For one, as a white woman, I don’t have much authority on the matter. I also think the discussion is way more complex than what it was made to be in feminist circles back in the day. However, what I find strange, and interesting, is how the discussion seems to have been almost completely forgotten. I haven’t come across much discussion about it in pieces on Y2K that I’ve read by chance, nor IRL. I just did a quick Google search and there are some articles and Reddit discussions on the trend and cultural appropriation, which mostly criticize today’s Y2K-followers for not acknowledging its roots in Black culture.

However, here and in other instances when the question is raised, it is quickly brushed aside. I read this article in the Danish newspaper Politiken about the resurgence of tribal tattoos which the article dubbed ‘neotribals’. The journalist mentions the critique of these tattoos when they were popular the first time around: that they originate with Indigenous groups in for example Samoa, where they experienced European colonizers forcing them to abandon the tattoo tradition while the same colonizers started getting them themselves. Confronted with this, an interviewed tattoo artist says that the resurgence of the style is something different than the original tribal tattoos, she keeps the motives abstract and that she wouldn’t tattoo something she didn’t understand. The question is left at that. I suspect that 10 years ago this would not have been accepted as an answer. Then, the artists and the tattoo owners would have to answer exactly how the tattoos are different and in what ways you can really just take a style from a culture and make it into something else which is then not appropriating.

I’m wondering whether this signals a kind of depoliticization of youth culture. After all, the original Y2K-style did come around at the end of history, pre-financial crisis. Have we moved past the politicization prompted by the 2007 financial crash? In a way, this seems counter-intuitive. There’s even more to feel politically about today: the invasion of Ukraine, the subsequent inflation and cost-of-living crisis, the mental health crisis, the climate crisis and so on. But perhaps the inumerous crises are too overwhelming to respond to politically? Perhaps it is also a sign of some backlash from the way the feminist community proliferated online in the 2010s which in spite of all the good things it carried with also tended to have endless, tedious discussions seemingly far removed from political organizing (again, the innumerable articles and blog posts on Gwen Stefani’s outfits). Maybe this can in some way be tied to the reactionary turn amongst the youth. Or maybe the trend needs to become even more in style before it will be criticized.

0 notes

Text

On climate denialism

I’ve been wondering why climate denialism keep getting so much research attention despite it feeling like a very 2010s topic. While climate denialism of course still exists, it seems like the consensus is that climate change is real and dangerous. Reading Bruno Latour’s ‘Down to Earth’ it however dawned on me:

The majority of this research has its roots in STS. One of the central assumptions of STS is that facts are socially constructed by different actors in the social field which taken together forms what we think of as ‘facts’ or ‘truths’. For these researchers then, it is unfathomable why nothing is being done about climate change, unless it is because what has been constructed as the truth is that climate change isn’t real. They subsequently conclude that this must mean that most of the actors (or actants) in the social field are climate denialists who together construct the fact that climate change isn’t real, and this leads to nothing being done about it. Their research then is centered around figuring out how this truth becomes constructed.

In a way, this is a comforting thought. If it is just a question of constructing the truth through the social field then it is possible that we through awareness campaigns can persuade enough actors to accept that climate change is real and dangerous and together, this can be constructed as the fact. This speaks into Latour’s idea of the main conflict line being between the ‘Terrestrials’, those that believe in the severity of climate change and the need to ‘come back to Earth’ to take proper care of it, and the ‘Moderns’, those that deny this and continues to subscribe to the project of Modernity. For Latour, the Moderns are the ‘main adversaries’, but this exists alongside the idea that these are, at the same time, potential allies which can be persuaded to join the Terrestrials. This idea of the possibility of persuasion corresponds with the view of politics as being essentially about socially establishing something as a fact.

However, isn’t it already the case that the climate crisis has been established as a non-disputable fact? I find the thesis that the overall sentiment or truth is that climate change isn’t real, hard to accept. What is rather the case is that although this is established as a fact, there are too many material interests involved in the continuation of burning fossil fuels. These material interests manifest in the everyday lives of regular people as a certain way of living that is hard to escape. Furthermore, the proliferation of ‘green’ economic discourse would suggest that capitalists have felt the winds of change and realized that they need to at least pay lip service to the need for climate change mitigation.

Of course, some would argue that this is also a kind of climate denialism: while not dismissing the existence of climate change, we are not realizing its entire scale. If we did, we would be acting completely different and in much more radical ways. However, claiming this significantly waters down the concept of climate denialism to a point where I doubt it has much usefulness. This does not mean that climate denialism is completely irrelevant or shouldn’t be researched. What I take issue with is using climate denialism to explain the lack of climate action. Here, I think we should at least additionally try to understand the accumulation drivers behind the continuation of fossil capital, as well as the attempt to greenwash this.

References

Latour, Bruno. 2018. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press.

0 notes

Text

From Selma James' introduction to The Power of Women and the Subversion of Community by her and Mariarosa Dalla Costa which I'm reading for a chapter I'm revising (endless revisions...). I'm reading it alongside other work from the 1970s and 80s by Italian autonomous Marxist feminists. Something that struck me is how many times decriminalization of sex work has appeared as a demand, formulated in a way which echoes sex workers' struggle today. For example here, in Leopoldina Fortunati's The Arcane of Reproduction:

Also: what a wonderful way to end a paragraph (again, Selma James):

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Running up that hill

Three times a week, I go running. Not particularly long or particularly fast, I don’t set goals for improvement or anything of that kind - I just run. However, spending a considerably amount of your time running necessarily leads to thinking about running as well. I also spend a lot of time reading, and eventually, I thought I would like to read about running. However, I could only find books written by men on the subject. “Why are there no books about women running?” I complained to my boyfriend. A couple of weeks later, Amalie Langballe asked the same question in Weekendavisen. Training for a Marathon, she similar to me had been unable to find satisfactory literary accounts of women running. Why does the gender of the author matter? Langballe points to that 1) these cismen know nothing of running with period pains or trying to find a fitting sports bra and 2) that these accounts often get very man-ish, lofty, and pretentious. She names the running classic What I talk about when I talk about running by Murakami as an example.

Despite this pretentiousness, I enjoyed reading Murakami’s What I talk about when I talk about running, but then I came to this section where he describes being passed by female runners on his jog:

Fatigue has built up after all this training, and I can’t seem to run very fast. As I’m leisurely jogging along the Charles River, girls who look to be new Harvard freshmen keep on passing me. Most of these girls are small, slim, have on maroon Harvard-logo outfits, blond hair in a ponytail, and brand-new iPods, and they run like the wind. You can definitely feel a sort of aggressive challenge emanating from them. They seem to be used to passing people, and probably not used to being passed. They all look so bright, so healthy, attractive, and serious, brimming with selfconfidence. With their long strides and strong, sharp kicks, it’s easy to see that they’re typical mid-distance runners, unsuited for long-distance running. They’re more mentally cut out for brief runs at high speed.

When Murakami himself is running, it is connected to his creation of art, to existential questions, almost to the human condition. When he sees women running though, he silently mocks them for their competitiveness, while at the same time admiring how they look. That he himself participates in multiple races a year where he cares a great deal about his performance, is apparently an entirely different case.

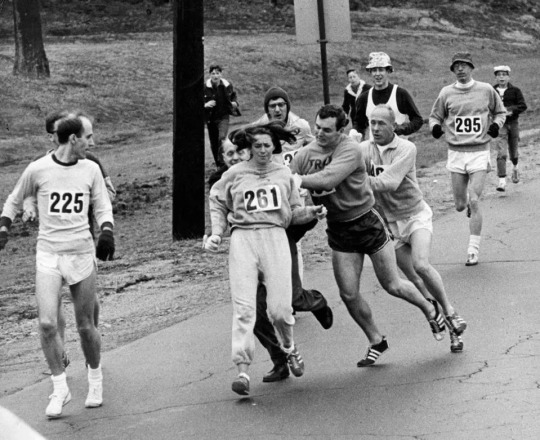

Whenever women runners do appear in literature, them running is always a sign of something being wrong with them. In Samlade verk by Lydia Sandgren, the main character Martin’s wife has purposefully disappeared without a trace. Prior to the disappearance, she was a runner, and in the story, these two facts appear connected. She runs long-distance because she is obviously running from something. As such, running appears as a compulsory, almost pathological, activity. It is not only in literature that running women are viewed with suspicion. At a party, I mentioned this to some friends. Sara mentioned the famous photo of Kathrine Switzer who in 1967 joined the Boston Marathon as the first woman runner. To avoid drawing attention to herself, she wore a hoodie. When it fell off, she was attacked by fellow male runners who wanted to stop her participation. Simon added an anecdote from the book Born to run about a woman in a small town in USA who starts running long distances. Everyone in the town thinks there is something wrong with her; in reality, she just likes running.

When women exercise isn’t view as proof of something being wrong with them, it is most often seen as a sign of her attempt to conform to beauty standards. In her essay Always be optimizing, Jia Tolentino analyzes the history of women’s self-optimizing, arguing that the recent decade’s proliferation of fitness culture should be understood as a continuation of the age-old pressure for women to mold their bodies in a certain way. We might have re-termed it to be about being ‘strong’ or ‘healthy’, but this is essentially what it is about. While I think there is a lot of truth in Tolentino’s diagnosis, which also includes a critique of the billion-dollar fitness industry and the way this optimizes our participation in capitalism, I think she is a tad pessimistic or determinist about women’s relationship to sports. Can’t we have a genuine interest in the sports discipline we partake in or truly enjoy the rush following physical exhaustion?

Of course, running is not only about the activity in itself (is there any activity there is?). But how come, for women, it must necessarily be connected to mental illness or body issues while for men, it is connected to art and existential questions? But the bigger question is, why are there so few women who write about running when evidently, there are so many women who run? One answer could be that women have less time than men due to our disproportionate participation in reproductive labor. Journalist Anders Legarth wrote the book Jeg løber [I run] based on a column series he wrote in the newspaper Politiken about starting to go long-distance running as a way to cope with the tragic death of his six-year-old daughter. I read the column sporadically and while I was sympathetic to it, I couldn’t help but think about what his wife was doing all those hours he was running – I guess she was probably taking care of their other two children. Perhaps women don’t feel the same need to write about every single hobby they pick up as something life changing. Or maybe it is just me who has not found the books yet. I will continue searching.

References:

Langballe, Amalie. 2023. ‘Afdæmpede besyngere’. Weekendavisen.

Legarth, Anders. 2018. Jeg løber. Politikens Forlag.

Murakami, Haruki. 2009. What I talk about when I talk about running. Vintage.

Sandgren, Lydia. 2020. Samlade verk. Albert Bonniers förlag.

Tolentino, Jia. 2019. ‘Always be optimizing.’ In Trick Mirror: Reflections on self-delusion. Random House.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading about the feminist movement in West Germany in the 70s and 80s this morning for an article I'm revising. I want to bring back Hexenfrühstück. (From Varietes of Feminism: German gender politics in global perspective (2012) by Myra Marx Ferree)

0 notes