Text

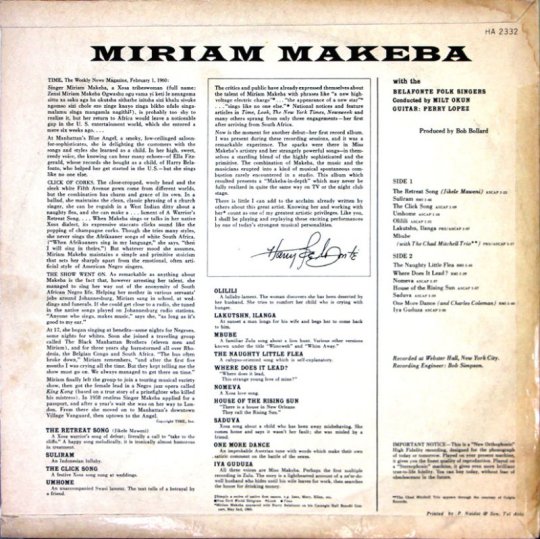

Self-titled: Miriam Makeba 60 years later

Miriam Makeba’s voice is so distinct you cannot miss it. Having been one of the few of her generation to gain fame and sustain her career for five decades, it’s hard not to identify the lilt in her inflections. Makeba is one of those who mastered the art of altering her tone with finesse, moving through phrases in soft and sharp tones breathing life to lyrics. The film adaptation of Chimamanda Adichie’s novel, Half of A Yellow Sun opens with the song “The Naughty Little Flea”. “The Naughty Little Flea” has a Calypsonian rhythm with vocals gliding delicately over the instrumental accompaniment. It’s these vocals that give Makeba away. I looked this song up and it led me to her self-titled album which launched her as an international this week 60 years ago.

Makeba was already a household name in the South African jazz scene having sung with The Cuban Brothers and The Manhattan Brothers in the early 1950s. She also founded the female jazz group The Skylarks in 1955 who are known for songs like Hamba Bhekile. Stints in these groups and a theatre role as Joyce in Todd Matshikiza’s King Kong ultimately lead to a solo career with the debut of Miriam Makeba released under RCA Victor on 11 May 1960.

The prominence of Calypso and Marabi (and sometimes the merger of the two) here likely speaks to the rise in Calypsonian music beyond the Carribean by way of the likes of Harry Belafonte. Makeba was taking up space on the mainstream music trend at the time while also putting local South African music on the map. Both genres grew out of a need black people had to create a vibrant culture in the middle of brutality. Staurt Hall’s article on Calypso and the Carribean diaspora in Britain traces the genre’s roots to pre-Easter weekend celebrations by enslaved people all the way to Carnival and across the Atlantic to the West Indies historic cricket win at Lords in England. Marabi was born from the townships that mushroomed in the early to mid-20th century. Artists began creating a sound that was a mash up of ragtime, swing, isicathamiya and jazz to create a sound that represented the flare and vibrance of lives black people led even in the midst of forced removals. The external American influences from which South Africans drew, make their way into this album in the form of “Where Does It Lead”, “House of The Rising Sun” and “One More Dance”.

Throughout the album is an air of nostalgia for black South African life especially the good parts. This may be tied to Makeba’s somewhat forced exile after the revocation of her passport in the same year. I consider this work crucial in piecing together South African history because we do not often here women’s voices. Makeba may have been pigeon-holed as the voice of black South Africa in regard to the fight against apartheid, but her voice as a witness to black society in general is not taken as seriously as we think. There is very little reflection on how she and Dorothy Masuka helped feminise the phenomenon of migrant labour in South Africa. Miriam Makeba opens with “Jikel’ Emaweni” (Retreat Song) originally sung by her bandmates, The Manhattan Brothers as song that conjures images of men dancing and engaged in stick fighting. Makeba’s Mbube recalls a drunken night most probably at a shebeen drawing from the culture of beer brewing for which black women in Johannesburg’s townships were known. Beer brewing was considered an illegal act for which Makeba’s own mother had been arrested. The image of a woman describing how very inebriated she had become after consuming copious amounts of alcohol can be seen as Makeba’s disruption of gender expectations. And she is not the only one. Dorothy Masuka’s use of tsotsi taal in interludes between songs brings to the fore the often ignored narratives of street smart black women. It is a strange act of erasure given that beer-brewing tavern-owning women must have been some of the toughest business people around.

You also cannot listen to “Mbube” without reflecting on the unjust history of Solomon Linda as it pertains to writing credits and royalties. Linda is considered one of the important proponents of Doo Wop and isicathamiya who composed “Mbube’s” melody for his group the Original Evening Birds. Mbube was duped to signing away his rights unaware of how little he was to benefit from his world famous composition- a mere 10 shillings. Further “compensation” was a job sweeping and serving tea at Gallo Studio’’s packing house, as Lydia Hutchinsion writes. Linda died in 1962 with only $22 in his bank account while the record company earned thousands in royalties. His family only started earning royalties in 2006.

There are also hints of the brutal particularly in the song “Lakutshon Ilanga” (another song originally sung by the Manhattan Brothers). Perhaps I am imposing this on the work by virtue of the history of which we are all aware. But by the time the album debuted, Sophiatown had already been destroyed. Apartheid’s Group Areas Act ensured the distruction of a cultural hub as important as the Harlem Rennaissance by forcibly removing black people from this suburb. “Lakutshon’ Ilanga” may be a love song but it's very likely that the story of a person searching for their loved one even as far as searching in the prisons, references mass arrests taking place at the height of the Defiance Campaign between 1952 and 1960. Even the Malaysian lullaby “Suliram” speaks to her awareness of South Africa’s slave history reminding all of us to think of our history in its entirety, not leaving out the descendants of enslaved South Asian people.

Her follow up albums like An Evening with Belafonte and Makeba released in 1965 see a Makeba who fully unmasks her political consciousness. There she pays tribute to political activists incarcerated on Robben Island, those who have been executed by the state and those who have gone for military training to liberate the country.

For now her focus on centering the every day, for those of us recalling this work reminds us that black people are more than just the injustices meted against them. In the midst of an unjust system are people living full lives.

This album is a beautiful display of Makeba’s versatility as a vocalist. The ability to sing life into lyrics, capturing the comical and the painful, is rare. Makeba creates images of a glorious cultural moment. Sophiatown may have been torn down but Makeba rebuilds it from the ground up in her larynx. Her percussive singing and the way her syncopated vocals fall between the instrumental accompaniment in order to create images of 1950s Johannesburg is mind blowing. She sings a reality she has lived and that’s why this album pierces the soul. The considered phrasing in songs throughout is a display of an artist raised on a diet of sublime musicianship which continues to be studied by some of today’s stunning jazz musicians. It’s the reason these songs refuse to be forgotten even if they are not celebrated as often as they deserve.

0 notes

Text

Bongeziwe Mabandla: Iimini

Iimini is not an album I can listen to in intervals. There is something about it that requires you to be still, to immerse yourself in the world of this heartbroken but optimistic storyteller. It pulls you in its world only to push you out so abruptly with that click of the door’s latch. Mabandla provides us with some simple yet sophisticated instrumentation, using countermelodies to swell the sound and submerge the listener into Iimini’s world.

In Iimini the days feel like they collapse into each other with no real demarcation in between.There is the very real sense that time feels suspended in the air as emphasised by the sustained chords in a song like “Masiziyekelele” which speaks to the notion of surrender and free-falling. The same applies for the lyric in “Zange”- ndaqonda mandizincame. Mabandla reflects on the joy and pain of loving someone. We see an artist resurrect memories so tangible you can imagine them taking place in real time.

The album contains songs that speak of falling deliriously in love as hinted especially in “Jikeleza'' and “Ndanele” however there is the sense that this won’t end well. Maybe it is the ominous Last Post- a bugle call played as a symbol of death and remembrance- heard at the tail end of “Ndanele”.Or “Salanabani” which shows up very early as a forewarning of the end. Love and heartbreak don’t follow a linear straight forward trajectory. Mabandla speaks to the cruel uncertainty of love; love that demands total surrender even as we don’t have a clear picture of what’s coming down the line. The music plays around with this uncertainty considering the arrangements, how they flow into each other, and how they rely on long drawn out chords even as there are rhythmic variations evidenced by broken guitar chords, psychedelic synths and falsetto vocals all layered to create a dreamscape for the memories recalled.

Sometimes the memory of love evoked here contains elements of possible reconciliation. Perhaps it is an ode to trying, to forgiving mistakes and correcting miscommunications. We know that the story is one of moving on in the end, but there are many other narratives where people return to each other. Mabandla invites us to surrender to that possibility as well. “Isiphelo” is not as final as it appears. We live in a world where people working things out is a possibility, that while the door may be closed it is never always locked. “Ndiyakuthanda” reminds us of this even though it may not be so for the protagonist of the story. “Andikwazi ukuyeka ukuthanda”, he confesses perhaps in acknowledging the reality of his heart even if the possibility of reconciliation is out of the question as signaled by the door we hear closing shut at the end. These two songs collapse into each other creating the effect that they are one and further re-emphasising the seesawing between pain and optimism in this love story, perhaps hinting at the possibility of reconciliation for Iimini’s lover’s.

Mabandla has created a timeless body of work. It offers an honest take on the complications of relationships with masterful arrangements and instrumentation that help us engage with ideas of love and loss in ways language can’t.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

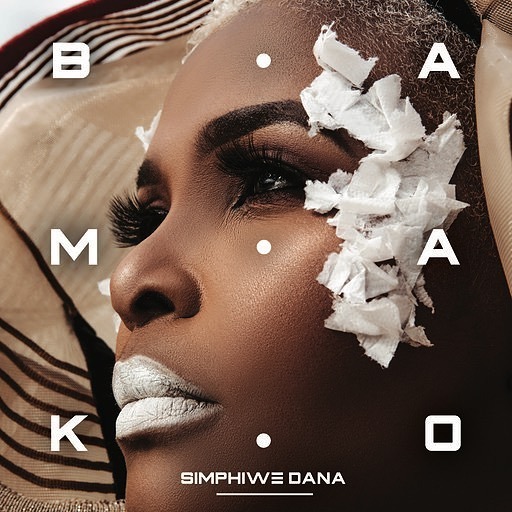

Simphiwe Dana: Bamako

Simphiwe Dana released her highly anticipated fifth studio album on 24 April 2020. In terms of anniversaries, it’s a big year for Dana whose albums Kulture Noir and Firebrand were released 10 and 5 years ago respectively .

It is a nod to the city after which it is named, Bamako. Out of all her albums this one is a display of vocal prowess we don’t often have the pleasure of hearing.Dana sounds like she is at her most powerful harnessing various textures and colours of her voice. It seems now more than ever is her time to experiment with range, not only just how high or low her voice can go, but the many ways she can contort it as a means of bringing her lyricism to life. Dana is considered one of this generation's voices of political consciousness. Professor Pumla Gqola’s A Renegade Called Simphiwe has gifted readers interested in the star, or readers interested in how we archive figures of our popular culture a detailed analysis to the meaning of the persona Simphiwe Dana as a cultural and political icon of this generation. But there are very few occasions when we reflect on the power of Dana as a composer.

Bamako is her latest invitation to think through how she uses the aural to celebrate progress in African music. Thinking about this album during Africa month is even more poignant as this opus pretty much celebrates the Pan-African strides music has made in the past 60 years since the ‘west wind’ (to borrow from Miriam Makeba’s song) of independence swept the African continent. African artists have a longstanding tradition of collaboration and musical cross-pollination. Dana is the latest to extend on this with her work with legendary Malian artist, Salif Keita and his band.

This collaboration’s significance is further accented by the upcoming 25th anniversary of Keita’s Folon. This is important to note as one of the songs, “Masibambaneni” is merged with Keita’s iconic single “Africa”. Keita has always been interested in advancing African music and particularly the connections between African artists probably far more than any other artist of his generation. Keita has always been at the cusp of genre bending with his voice belting out notes over the sound that is a combination of electronic and traditional instrumentation. Keita, who is of royal descent traceable to Soundiata Keita who founded the Mandinka Empire in 1240 along with his peers like Youssou N'dour, Mory Kante and Oumou Sangare who hail from various parts of this region musically hold together the remnants of a history that stretched much further than the confinements of the Berlin Conference.

There is an aspect of the album that guides us to perceive Bamako in a specific way. The opening song, the experimentation onomatopoeically with synths, an imitation of the opening bars invites warmth to our ears. There is the sense that Dana as producer wants us to experience the city that inspired this work. Of course there are the instruments which are distinct to Mali however the arrangements in their entirety bring the city to our ears. Dana takes us along on her pilgrimage to one of Africa’s ancient cultures. She also does something I doubt has ever really been successfully executed by an artist so consistently. The vocal and instrumental traditions of two very distinct countries converge on this album so neatly and effortlessly, making this collaboration between these genius artists ever more exciting. Both are interested in listeners experiencing our genres anew, smashing the borders we create by categorizing creativity and unknowingly or knowingly locking artists in labels that don’t quite make sense to musicians interested in the boundlessness of composition.

Genre bending allows us to actually listen to music and what it communicates to our spirit.

A lot of young South Africans are likely to have been introduced to Keita’s work among other West and East African icons like Kadja Nin and Ismael Lo through the “Simunye: We Are One” era of SABC 1 when the channel would stream Channel O.

For those who weren’t born then, there is Bamako.

One of the reasons the album is of interest to me is because of the historical links we listeners can make. This year is a historically important year for South Africa. Many have honoured the release of South Africa’s first black president. However another unprecedented moment took place this year 110 years ago. On 21 September 1910 Mpilo Walter Benson Rubusana (WB Rubusana) won a seat in the Cape Provincial Council of the Union of South Africa, the same year the Union was officially founded. This history comes to mind when Simphiwe sings, “Zemk’ inkomo magwalandini” which borrows the title of Rubusana’s poetry collection- the first by a black writer to ever be published. Born in 1858, a year after the infamous Cattle Killings of pre-colonial Eastern Cape, Rubusana’s decision to even campaign for a seat in the Council was sparked by betrayal. Of this moment public intellectual Pallo Jordan writes:

“Walter Rubusana’s candidacy in the Provincial Council elections of 1910 was correctly considered by all observers as a bold step indeed. Two years previously, in an editorial written by John Tengo Jabavu, the African electors of the Cape had assured the white electorate that they felt no need to put forward African candidates in elections because of their faith in the fairmindedness of their white counterparts. Such faith had been found to be misplaced when the Constitution for the Union of South Africa was drawn up with its notorious ‘colour bar’ clauses. Rubusana’s candidacy was a response to this affront, as well as an act of political self-assertion on the part of the African electorate of the Cape who had too long allowed themselves to live in the shadow of the white liberal political establishment. Rubusana was chosen as the instrument for these purposes because of the prestige he enjoyed within the black community and in recognition of his personal contribution to the political struggles of that community.”

The second is the song “Mkhonto” whose arrangement sounds very similar to igwijo in honor of Solomon Mahlangu, an Umkhonto We Sizwe operative executed by the apartheid regime on 6 April 1979. Some of South Africa’s popular struggle songs were composed by musically trained vocalists. For example the Port Elizabeth born activist, poet, dancer, actor and singer Vuyisile Mini who penned “Ndod’ Emnyama” was a bass singer in the PE Men’s Vocal choir. South Africa has a rich choral culture which is not surprising that amagwijo were composed so easily on the spot. It’s also probably why they are mostly in rondo form given their shortness. They never really digress beyond the couplet, which is simply the main melody and slight change that feels like a verse. “Zabalaza” is another that uses the igwijo model whose effect is closely tied to repetition for the stirring of emotion. The beauty of a vamp is though you sing the same melody, you actually never sing it the same way. Dana achieves this through the dynamics in her voice-how it rises and falls at various points.

As it pertains to the political, Dana expresses disdain for the decline in our state of affairs, where it appears that a people-centred political mandate has been abandoned for looting of resources and abuse of power by those elected in power. Dana’s further reference of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s words spoken, “singayisusa nanini' in “Uzokhala”' is an artist reminding people of their power to bring about revolution, while using “Usikhonzile” to imagine humane leadership for which the likes of Rubusana are remembered.

For the most part Dana preoccupies herself with love and heartbreak with some tracks like “Kumnyama” and “Bye Bye Naughty Baby” and taking on the feel of preludes scaffolding the albums overarching theme. Dana has never gone down this path in terms of themes as far as she has with this album. Black South African artists are usually expected to provide political commentary, they are barely expected to bring their humanity in all its nuances to their work. Dana talking so openly about the complexities of love is unexpected from an artist like her. This work sees Dana unburden herself from this weird expectation proving just how very versatile her pen is. Love in Dana’s world traverses various landscapes. There is love in ethical leadership as she shows in “Usikhonzile”. There is also love in closing the door on relationships that aren’t reciprocal. And as demonstrated in “Mr I” there is love in acknowledging the difficulties of leaving, in exhausting all possibilities as an attempt to salvage a relationship. This work looks closely at the debris left in the wake of a broken heart and she acknowledges that sometimes there are no easy answers if at all, and there is no way forward except to retreat and lick wounds.

Dana’s music is heavy laden with meaning. There is never anything final about the subject matter she explores in her music. Listening to this album feels like being asked a series of questions. Dana pushes us to think differently about the world. Where lyrics fail, it is music that fills in the gaps. I particularly enjoy the weightedness in the introductory verse of “Gwegweleza”, a song that addresses the unfair financial burdens placed on single mothers by absent fathers. Because Dana is interested in change, there is the sense that she asks men whether they are going to continue with their deadbeat behavior. For how long are we going to exist in a world where an alarmingly high number of men continue to be irresponsible?

Her deliberate and careful structuring of the music with her legendary co-producer is reflective of an artist who not only aims to entertain, but who wants us to imagine with her a better world, and from there proceed to bring it to existence.

2 notes

·

View notes