Text

Why were the Knights Templar so interested in Harran?

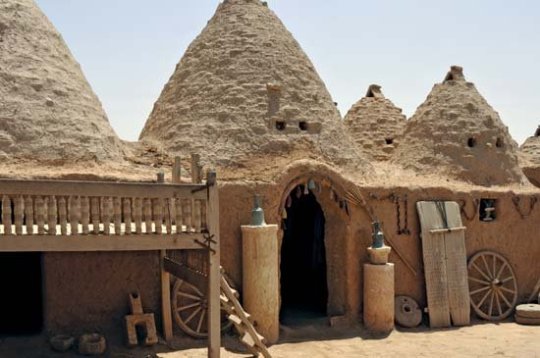

Harran is one of the oldest cities in the World. Located in southern Turkey, a remarkable feature of this ancient place is its beehive-shaped adobe houses, built entirely of mud without any wood. Their design makes them cool inside and is thought to have been unchanged for at least 3,000 years. Some were still in use as dwellings until the 1980s. Harran dates back to at least the Early Bronze Age, to sometime in the 3rd millennium BC.

Renowned as a point on the Silk Road , there are many references to this ancient place in the Bible and, for example, its trade with the Phoenician city Tyre in ‘choice garments, in clothes of blue and embroidered work, and in carpets of colored stuff, bound with cord and made secure’ (Ezekiel 27:23-24).

It is perhaps most famous as the city of Abraham. His birthplace, Sanliurfa, is close by and Harran is the place where his father Terah went to die. My own interest in this city is not, however, in its Biblical connections, fascinating though they are, but in its more esoteric history.

The Christian interest in Harran and the ancient kingdom of Edessa

Harran’s close neighbor, Sanliurfa, holds a clue to this hidden aspect. Sanliurfa has undergone many transformations over the millennia. Most curiously, in the 12th century, when Sanliurfa was a Christian kingdom that went by the name of Edessa, it attracted the attention of the Knights Templar.

There seems to be some significance in St Bernard of Clairvaux, and not the Pope, preaching the Second Crusade at Vezelay in Eastern France, not in order to defend Jerusalem but to rescue Edessa after its capture by the Seljuk Turks in 1145.

The question is, why? Why did St Bernard, who was responsible for helping to create the Knights Templar, take such an interest in this land-locked city-state which, as writer Adrian Gilbert points out, was of no strategic importance on the wrong side of the Euphrates? (Adrian Gilbert Magi – the Quest for a Secret Tradition, Bloomsbury, London, 1996 p. 191) It was quite a military undertaking after all, and not an obvious destination.

Maybe the Knights Templar knew that Edessa could have been the original ‘Ur of the Chaldees;’ the place where the Chaldean Magi had spent time. In the 1920s, Sir Leonard Woolley claimed that the ‘Ur of the Chaldees’ was his excavation of the city of Ur in southern Iraq. What he found was spectacular and extensive: huge quantities of artifacts dating back 3000 years, and much gold - including a beautiful golden sculpture of a ram caught in a thicket.

Many of his finds are on display in the British Museum. But important though his find was, I am not convinced that this was the Ur of the Bible. ‘Ur’ is a common word found in ancient times as it has the meaning of ‘foundation’ and can be found in the name of Jerusalem – ‘Uru-shalom’ – meaning ‘place of peace.’ It makes more sense that the Chaldean Ur was further north, not least as Abraham refers to his conflicts with the Hittites, who were based in central Turkey.

Is there hidden knowledge in Harran?

The Chaldean magi, an elite of wise men and skilled in the arts of divination, had taken refuge in the remains of the Hittite empire in central Turkey at least a thousand years before the Knights Templar arrived; and it is possible that something remained of their occult knowledge in the area. But it is just as likely that the real focus of the Templar attention was Harran itself.

It is important to reflect at this point on what might have been the genuine mission of the Knights Templar. There is no doubt that St Bernard played a key role in creating the cover story that this select group of religiously inspired crusaders existed to protect the routes to Jerusalem. But given the low numbers of Templars, at least to begin with, this explanation does not make sense.

What is more plausible is that they had a presence in the Near East because, after the First Crusade in 1097, St Bernard and others from the Court of Burgundy became aware of occult knowledge contained in a body of writings known as the Corpus Hermeticum - considered to be ‘older than Noah’ - having been composed by Hermes Trismegistus and therefore of great interest. And one group of people who knew a lot about the Hermetica was the Sabians, who lived in Harran at the time of the Crusades.

What made Harran unusual in the 12th century was that it was not Jewish, Islamic, or Christian. Its main temple, eventually destroyed by the Mongols in 1259, was dedicated to the Mesopotamian Moon god, Sin . It was also famous as a center of alchemy, as practiced by the Sabians who regarded Hermes as the founder of their school.

A Sabian sanctuary

The Sabians’ distinctive form of alchemy focused on metals, especially copper, and minerals, rather than gold. In the view of some writers, this distinction indicates a very early tradition, possibly going back to 1200 BC, when copper was the chief metal (Jack Lindsay The Origins of Alchemy in Graeco-Roman Egypt, Frederick Muller, London, 1970). There is little doubt that the Sabians’ beliefs and practices date back into ancient times and that they had strong links with Egypt. Indeed, it is possible that the name ‘Sabian’ derives from the ancient Egyptian word for star, sba, and they may have been ancient refugees from Egypt.

The Sabians could have been the last remnants of a priesthood which mostly disappeared from Egypt in the 4th century when Romano-Christians destroyed what was left of Egyptian temples. As a result of that persecution, they may have found their way up the trade routes to Harran on the northern Euphrates where they felt safe enough.

What kept the Sabians safe and allowed them to continue with their practices was a reference to them in the Koran. The Koran acknowledged that the Sabians were of the religion of Noah and therefore accorded them respect. The precariousness of their existence is, however, recorded in the story of the Caliph of Baghdad who passed through Harran in 830 AD.

He wanted to know if those who dressed differently were ‘people of the book’ (i.e. the Koran or Bible). Fortunately, he accepted the response that the Sabians’ ‘book’ was the Hermetica, their prophet was Hermes, and they were the Sabians referred to in the Koran and so they were spared from death as infidels.

Little did the Caliph realize how much the Sabians had contributed to his own culture, Sabians helped to found the city of Baghdad in 762 AD and turn it into a great seat of learning. The Sabians were a significant ‘conduit for the transmission of ancient wisdom to the Arabs, especially to the Sufi and the Druze (Adrian Gilbert op cit,1996, p70) .

It was a Sufi alchemist by the name of Jabir ibn Hayyam who had in his possession one of the oldest copies of the most famous Hermetic texts, the Emerald Tablet , and who wrote the magical tales of a Thousand and One Nights . He was skilled in mathematics, medicine, and other sciences and was keen on disseminating knowledge of the Pythagorean principles of number (Baigent & Leigh - The Elixir & The Stone, Viking, London, 1997 p.41) .

Above all, it is thanks to the Sabians, and to the city of Harran, that so much knowledge relating to ancient civilization, to the Egyptians and others, was preserved throughout the Dark Ages and from which we can once again benefit.

Author: Lucy Wyatt

Source: ancient-origins.net

1 note

·

View note

Text

Becoming a secret organization

The Knights Templar were originally a very open organization with non-members being allowed to enter the Templar homes and the Templars were known to do good in the towns and cities that they inhabited. The restrictions and the traditions of the order were widely known by those who were interested and prior to the 14th century there were few rumors about secret initiations or dealings of the Templars.

That changed once the Templars came under attack by King Phillip IV. The members of the Order suddenly had to find ways to hide who they were in order to avoid arrest and torture. Many of them shaved their trademark beards though it was not enough to evade detection. While having a beard was not part of the rules of the order the trademark mantle was.

Once Pope Clement V dissolved the order in 1312 there were many rumors that the Templars found a way to exist out of the public eye. The papal orders required that much of the Templar holdings be turned over to another Christian order, the Knights Hospitaller. However, some Templar organizations changed their name to the Order of Christ. Some credited the Knights Templar as being too powerful to be shut out even by the Pope and the King, which is why rumors persisted as to their existence underground.

The rumors were helped by what happened at the execution of Grand Master De Molay in March 1314. As he was being burned at the stake he maintained his innocence and devotion to God. He loudly proclaimed “God knows how is wrong and has sinned. Soon a calamity will occur to those who have condemned us to death.” Pope Clement V died a month later and King Phillip IV died in a hunting accident before the year was out.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The French Knights who escaped prosecution

Templars were prosecuted and murdered after being convicted of heresy in the beginning of the 14th century. Less popularly known is the story of a group of French Templars who managed to escape. Even the Templar organization as it exists today isn’t sure what the full story was.

According to the popular story, all the Templars were arrested on Friday the 13th, in October 1307. But it’s also been speculated that some escaped persecution. Estimates of numbers in the order at the time are somewhere around 3,000, but we only have records of the interrogations—and the fate—of about 600 of them.

If a massive, coordinated, country-wide series of arrests would have been impossible, many Templars had a chance to get out. Records tell of authorities pursuing some of the escaped knights, and one document in particular has been languishing in French archives for centuries. Only proved authentic recently after handwriting comparison, the document is a list of 12 names that were of particular interest to authorities.

Historians have identified a couple of these names and connected them with the reasons they were of such great interest. Humbert Blanc was a Crusader and master of Auvergne; he was captured and put on trial in 1308, denying all charges (save the secrecy of the order, which he thought unnecessary). Records say he was put in irons, but we’re not sure what happens to him afterward. A couple other names on the list—Renaud de la Folie and Pierre de Boucle—crop up again in trial records, but it’s difficult to tell why they were so important. The spelling of names is less than consistent, making it hard to connect names and deeds.

As for the others on the list, just why they were special targets of the authorities above others is a mystery. One, Guillaume de Lins, even has a question mark next to his name on the list. He is perhaps Gillierm de Lurs, one of the officers in charge of ceremonies and receptions, but again, spelling gets in the way of establishing anything for sure. We don’t know much about Hugues Daray, either, or Adam de Valencourt, save that he was an elderly man who had, for some reason, joined the Templars twice.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The special diet that kept the Knights Templar fighting fit

GRAYBEARDS WERE THIN ON THE ground in the 13th century. For even wealthy landholding males, average life expectancy was about 31 years, rising to 48 years for those who made it to their twenties. The Knights Templar, then, must have seemed to have some magical potion: Many members of this Catholic military order lived long past 60. And even then, they often died at the hands of their enemies, rather than from illness.

In 1314, Jacques de Molay, the order’s final Grand Master, was burned alive at the age of 70. Geoffrei de Charney, who was executed in the same year, is usually said to have been around 63. This longevity seems to have been almost commonplace. Fellow Grand Masters Thibaud Gaudin, Hugues de Payens, and Armand de Périgord, to name just a few, all lived into their sixties. For the times, this would have been positively geriatric.

“The exceptional longevity of Templar Knights was generally attributed to a special divine gift,” writes the Catholic scholar Francesco Franceschi in a journal article about their salubrious practices. But modern research suggests an alternative: The order’s compulsory dietary rules may have contributed to their long lives and good health.

Contrary to many modern portrayals, the Knights seem to have lived genuinely humble lives, in service to God. Their dietary choices and obligations reflect this. Though the order grew rich from carefully handled donations and by safeguarding traveling pilgrims’ money, the men themselves took formal vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. They were not permitted even to speak to women. For nearly 200 years, the order thrived across Europe, peaking at around 15,000 members by the end of the 13th century. Most of all, they were expert warriors, and their ranks comprised some of the best fighters, warriors, and jousters in the world.

Early in the 12th century, the French abbot Bérnard de Clairvaux helped assemble a long and complex list of rules, which structured the knights’ lives. This rulebook became known as the Primitive Rule of the Templars, and drew from the teachings of the saints Augustine and Benedict. But many of the rules originated in the order. Though the document was completed in 1129, writes Judith Upton-Ward, the Templar Knights had already been in existence for several years, “and had built up its own traditions and customs … To a considerable extent, then, the Primitive Rule is based upon existing practices.”

The rules were many and various. The knights were to protect orphans, widows, and churches; eschew the company of “obviously excommunicated” men; and not stand up in church when praying or singing. Even sumptuary laws prioritized humbleness: Their monk’s habits were one colour alone, though on warm days between Easter and Halloween, the rules decreed, they were allowed to wear a linen shirt. (Pointed shoes were always forbidden). But the rules also extended into their dietary practices: How they ate, what they ate, and who they ate with.

Their meals do not seem to have been raucous affairs. Knights were obliged to eat together, but to do so silently. If they needed the salt, they had to ask for it to be passed “quietly and privately … with all humility and submission.” A sort of buddy system existed, partly due to a mystifying “shortage of bowls.” This may have been more a show of abstinence than anything else, like the knights’ emblem, which was of two men sharing a horse.

The knights’ diets seem to have been a balancing act between the ordinary fasting demands on monks, and the fact that these knights lived active, military lives. You couldn’t crusade, or joust, on an empty stomach. (Although the Knights Templar only jousted in combat or training—not for sport.) So three times a week, the knights were permitted to eat meat—even though it was “understood that the custom of eating flesh corrupts the body.” On Sundays, everyone ate meat, with higher-up members permitted both lunch and dinner with some kind of roast animal. Accounts from the time show that this was often beef, ham, or bacon, with salt for seasoning or to cure the meat.

It’s likely that these portions were considerable: If the knights weren’t allowed meat due to a Tuesday fast, the next day it would be available “in plenty.” One source suggests that cooks loaded enough meat onto their plates “to feed two poor men with the leftovers.”

But on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays, the knights ate more spartan, vegetable-filled meals. Although the rules describe these meals as “two or three meals of vegetables or other dishes eaten with bread,” they also often included milk, eggs, and cheese. Otherwise, they might eat potage, made with oats or pulses, gruels, or fiber-rich vegetable stews. (The wealthier brothers might mix in expensive spices, such as cumin.) In their gardens, they grew fruits and vegetables, especially Mediterranean produce such as figs, almonds, pomegranates, olives, and corn (grain).* These healthy foodstuffs likely also made their way into their meals.

All the while, brothers drank wine—but this too was restricted. Everyone had an identical ration, which was diluted, and they were advised that alcohol should “not be taken to excess, but in moderation. For Solomon said … wine corrupts the wise.” In the Holy Lands, they allegedly mixed a potent cocktail of antiseptic aloe vera, hemp, and palm wine, known as the Elixir of Jerusalem, which may have helped accelerate healing from injuries.

Franceschi describes other regulations beyond the Primitive Rules that were “specifically designed to avoid the spreading of infections.” These included mandatory handwashing before eating or praying, and exempting brothers in charge of manual tasks outdoors from food preparation or serving. Some of these innovations, picked up without any awareness of germs, may have resulted from interactions with Arab doctors, renowned during the period for their superior medical knowledge. By medieval medical standards, Templar Knights were at its apex, able to treat many illnesses and to take care of their weak.

The order was one of the richest in the world—yet these rules prevented the knights from sitting on their laurels or gorging themselves on fatty, cured meat. In fact, many of these rules resemble modern dietary advice: Lots of vegetables, meat on occasion, and wine in moderation. A meal fit not for a king on a throne, but a knight with some serious crusading to do.

Source: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-the-templar-knights-ate

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Only the knights wore the Templars’ distinctive regalia

The Templars were originally divided into two classes: knights and sergeants. The knight-brothers came from the military aristocracy and were trained in the arts of war. They assumed elite leadership positions in the order and served at royal and papal courts. Only the knights wore the Templars’ distinctive regalia, a white surcoat marked with a red cross. The sergeants, or serving-brothers, who were usually from lower social classes, made up the majority of members. They dressed in black habits and served as both warriors and servants. The Templars eventually added a third class, the chaplains, who were responsible for holding religious services, administering the sacraments, and addressing the spiritual needs of the other members. Although women were not allowed to join the order, there seems to have been at least one Templar nunnery (source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Templars).

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Templar, also called Knight Templar, is a member of the Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, a religious military order of knighthood established at the time of the Crusades that became a model and inspiration for other military orders. Originally founded to protect Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land, the order assumed greater military duties during the 12th century. Its prominence and growing wealth, however, provoked opposition from rival orders. Falsely accused of blasphemy and blamed for Crusader failures in the Holy Land, the order was destroyed by King Philip IV of France.

2 notes

·

View notes